21

BECAUSE THE HEART SUTRA is a Mahayana text, practitioners in the earlier Theravada tradition, which developed largely in South and Southeast Asia, don’t recite it. Buddhists in Pure Land schools, whose main practice is the invocation of the name of Amitabha Buddha, don’t recite this sutra, either.

Practitioners of some schools of Tibetan Buddhism, which are increasing their deep and wide presence in India as well as in the Western world, do recite the longer text of the sutra. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s Heart of Wisdom Teachings, offered publicly in 2001 and later in book form as Essence of the Heart Sutra, are based on the Gelugpa transmissions he received as a lineage holder. When he teaches, he has the Heart Sutra recited first in one of the languages of the people attending, so that each day on a retreat they hear it in a different language. In many centers of the Gelugpa, Nyingma, and Kagyu schools worldwide the sutra is chanted daily.

In other schools of Tibetan Buddhism in the West, the sutra is recited weekly, monthly, or on certain occasions or retreats. There are also centers where sutras are not recited. Some teachers assign students the recitation of the sutra one hundred, one thousand, or even one hundred thousand times for a certain period of time as their personal practice. In 1973, the well-known teacher and meditation master Chögyam Trungpa wrote a commentary on The Sutra on the Essence of Transcendent Knowledge.1

In almost all Zen Buddhist monasteries, centers, and meeting groups worldwide, meditators make daily recitations of this scripture. The enthusiasm of Tibetan and Zen practitioners in North America and Europe seems to have contributed much to the popularization of the Heart Sutra around the globe.

The Japanese Buddhist scholar Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki (1870–1966) played a catalytic role in introducing Zen to the West with the extensive essays he wrote in English before and after World War II. His eloquent descriptions of the intriguing paradoxes in the philosophy, art, and culture of Zen evoked a widespread curiosity and profoundly influenced the Beat generation. Consequently, the Japanese loanword zen became a household word in English. This type of Buddhism, initially developed in China, is called chan in Chinese, so “Chan” is actually the more precise name of the school. However, the first impact of the word “Zen” brought by Suzuki was so strong that the odd term “Chinese Zen” is commonly used. (I apologize to Chinese speakers that I am one of those who use the word “Zen” to include “Chan.”)

From the early intellectual focus in the West, the actual practice of meditation evolved. In the 1950s, Zen teachers became increasingly prominent in North America and Europe. Among these were Shunryu Suzuki and Taisen Deshimaru from Japan; Seung Sahn from Korea; and Hsuan Hua and Sheng Yen from China and Taiwan. In 1966 Thich Nhat Hanh was exiled from Vietnam and eventually settled in France. Under the guidance of these teachers, Zen groups, centers, and monasteries developed their daily activities centering on meditation.

Recitation of the Heart Sutra is a regular part of Zen practice and is often conducted in a service after meditation. A chant leader announces the title in a melodic way, for example, “Maka Hannya Haramitta Shingyo” in Japanese or “Maha Prajna Paramita Hridaya Sutra” in a form familiar to speakers of English, borrowed from Sanskrit. Then all participants chant the text aloud, often accompanied by the chopping sound of a wooden catfish-shaped drum: “No eye, no ear, no nose . . .” My wife, Linda, says, “I like denying things. So when I chant the Heart Sutra and deny everything all the way, I get exuberant!” The high-volume synchronized recitation of the sutra by the gathering of meditators contrasts with the stillness and silence of meditation practice. It is a solemn but dynamic and joyous activity.

It makes sense that everyone present at a funeral or an ordination service cries out, “GATÉ GATÉ PARAGATÉ . . .” (Gone, gone, gone all the way . . .) Not only that — this sutra is chanted at all events, including weddings and the celebration of childbirth. Indeed, the Heart Sutra is the most commonly recited text on all Zen Buddhist occasions the world over.

In the West, the sutra is sometimes chanted in Chinese or Korean alone, in which case the text is incomprehensible for most of the participants. In a way, it serves as a long version of a dharani, or mantra,2 which helps people to gather their minds away from the intellect. In some cases, for that reason, the meanings of words in the text are intentionally not explained. Nevertheless, people seem to enjoy chanting the incomprehensible foreign versions.

In Antwerp, Belgium, I noticed that all chanting was done in Japanese. When I asked Luc De Winter, the teacher of the Zen center, “Why don’t you chant in Flemish or French?” he said, “Our sangha members speak six languages. It’s not fair to use one of the languages. So we chant in Japanese.” Thus, most participants are on equal footing.

In most cases, however, the sutra is chanted in English, French, German, or whatever language matches the region where it is chanted. Sometimes they chant in one of the East Asian languages and then in their own language.

All translations of the Heart Sutra used in Zen schools originate from Xuanzang’s shorter version of the sutra. D. T. Suzuki’s rendering is the basis for most English translations.3 In some cases, people also seem to have checked with Edward Conze’s translation.4 (Suzuki’s and Conze’s translations of the sutra are included in the “Terms and Concepts” section of this book.)

One remarkable thing about the Heart Sutra in the Western world is that there are so many versions even within one language region. Zen centers and their sub-centers often have their own versions. It seems that not so many people have checked the original Chinese version; rather, they have made superficial changes to suit their need for chanting and explanation of the meanings.

Recitation of the Heart Sutra is often followed by a melodic prayer called “dedication of the merit.” For example, in groups affiliated with San Francisco Zen Center, the prayer is: “We dedicate this merit to: Our great original teacher in India, Shakyamuni Buddha; our first ancestor in China, great teacher Bodhidharma; our first ancestor in Japan, great teacher Eihei Dogen; our compassionate founder, great teacher Shogaku Shunryu; the perfect wisdom Bodhisattva Manjushri. Gratefully we offer this virtue to all beings.” In the Order of Interbeing founded by Thich Nhat Hanh, practitioners recite “Sharing the merit” after chanting the Heart Sutra or another sutra: “Reciting the sutras, practicing the way of awareness gives rise to benefits without limit. We vow to share the fruits with all beings. We vow to offer tribute to parents, teachers, friends, and numerous beings who give guidance and support the path.” These kinds of prayers represent the aspiration, practice, and commitment of those who practice meditation.

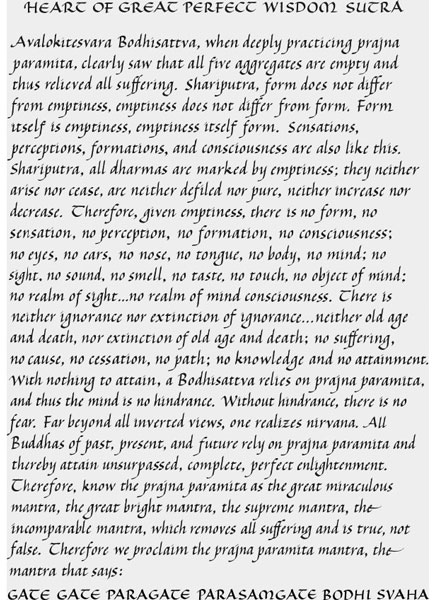

FIG. 19. The Heart Sutra in English. San Francisco Zen Center version.

Next, at San Francisco Zen Center, for example, practitioners put their palms together and chant: “All buddhas, three times, ten directions, bodhisattva mahasattvas, wisdom beyond wisdom, maha prajna paramita.” This is like a simple listing of nouns. In English a sentence is not formed without a verb, so I would propose the following translation: “All awakened ones throughout space and time, honorable bodhisattvas, great beings — together may we realize wisdom beyond wisdom.” Thus, this prayer becomes an acknowledgement of all buddhas and bodhisattvas in the past, present, and future, and the expression of everyone’s intention to realize wisdom beyond wisdom together. With their chanting, practitioners confirm the experience of undividedness, which is the essential message of the Heart Sutra.