After Alison arrived back in Washington, D.C., Arnold asked him for a report on Operation Thursday and advice on what to do with the two new ACGs being formed. Alison said that the CBI could use another group and that perhaps the other group could be sent to the Pacific theater for use in the invasion of the Philippines. Liking the idea, Arnold ordered Alison to go to Australia and make a pitch to FEAF commander General Kenney to take an Air Commando group.

Alison made a quick trip out to the southwest Pacific in late June carrying a letter from Arnold describing the Air Commandos.1 Arnold wrote about “the broad field which exists for operations involving the movement by air of large ground forces (airborne and ground infantry) and the maintenance and supply of these forces for an extended period from the air. The Air Forces will not be able to play their full part in major campaigns until they are able to move and supply troops without dependence on surface transportation.”2 The new ACGs and CCGs being formed were tailor-made for this activity, Arnold believed. He also felt that the CBI was not the best place to send them, saying that “circumstances” in that theater would deny them the bold and imaginative employment needed. “We are willing to go a long way on this project provided the expenditure is justified,” Arnold concluded.3 Kenney, who was MacArthur’s air leader, was requested to give his opinion on the subject as soon as possible.

It did not take long for Kenney to become enthusiastic about the Air Commandos. Perhaps recalling his own proposal back in 1942 for an Air Blitz Unit and always eager to get his hands on men and planes for his undermanned Fifth Air Force and Thirteenth Air Force, Kenney was ready to take the new units now. “It did not require any argument from you or Alison to sell us on this idea,” he replied on July 5. “My immediate reaction is to ask you to send all or any of these units as soon as possible. . . . These types of operations are right down our alley. The organization, the equipment, the method of employment, and, in fact, the whole idea fits in perfectly with the tools, necessities and experience of this theater.”4

Kenney requested that if the Air Commando and Combat Cargo units could reach him not later than October, they would be employed in an “eye-opener” of a tactical role. This was most likely at the upcoming assault of Sarangani Bay on Mindanao. He also wanted both Alison and Cochran to come over. “These two men are cracker-jacks and I will need them to operate these expeditions,” he explained.5 Kenney finished, “I think it is vital that we switch to airborne operations and air supply. Boats are alright in their place but the Navy fights a different war and the Air Force here would like nothing better than to rely solely on air transportation.”6

Kenney did not get Cochran, but he did receive Alison. Not long after returning to the United States, Alison was ordered back to Kenney’s headquarters, where he was to assist in drawing up plans for the use of the Air Commando and Combat Cargo units during the invasion of the Philippines.7

It should be noted that although Kenney was eager to exploit Alison’s and Cochran’s expertise on Air Commando operations, the tenor of his letter suggests that he was really interested in the air transportation and cargo supply side of those operations. And indeed, the early enthusiasm for the concept of self-sustained and self-contained airborne operations behind enemy lines had begun to wane in Washington and in the CBI as the Allied offensives in the Pacific and Burma had begun to accelerate. Such airborne operations were no longer viewed as necessary. Rather, the matter of air transport had assumed a much larger role in the minds of planners. Thus, though the 3rd ACG would be active in MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) command, it would be in an entirely different manner than that of the 1st ACG in Burma.

The last of the World War II Air Commando groups, the 3rd ACG, was activated at Lakeland AAF on May 1, 1944. Pending the arrival of Colonel Olson, Maj. Klem F. Kalberer was the acting group commander. The 3rd ACG was organized similarly to the 2nd ACG—two fighter squadrons with twenty-five P-51s each, a TCS with sixteen C-47s and thirty-two gliders assigned, three liaison squadrons of thirty-two L-5s and four UC-64s each, four ADSs, and a medical dispensary.8 At the time of its activation, the 3rd ACG consisted of only the 3rd Fighter–Reconnaissance Squadron, the 4th Fighter–Reconnaissance Squadron (both of which were soon redesignated fighter squadrons), the 334th ADS, and the 335th ADS.

Many of the group’s original cadre of fighter pilots came from the 2nd ACG’s 1st Fighter Squadron, to which they been reassigned from the 23rd Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, the 97th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, and the 76th Tactical Reconnaissance Group, which had all been disbanded in April. Many of these fliers, though, were soon transferred again and replaced by pilots with “reputations for exceptional gunnery ability.”9 Since no aircraft were yet assigned to the 3rd ACG’s fighter squadrons, most of the fighter pilot personnel were granted leave in May. Men in the ADSs, on the other hand, underwent intensive training, as befits newly organized units.10

Over the next couple of months the remainder of the group’s units were activated. Most of these were stationed far from Lakeland, which was a precursor of how the group would actually be used in combat. On May 1 both the 318th Troop Carrier Squadron, Commando, and the 343rd Airdrome Squadron, Commando, were activated at Camp MacKall. For the time being they remained at that station working with gliders and paratroopers from nearby Fort Bragg. Only in mid-August, when the two units moved to Dunnellon AAF, did they work jointly with the rest of the 3rd ACG. Their members did not meet Olson until September 5, when he gave a talk on what their mission was and what he expected of them. His talk was received favorably, and the men returned to their training with renewed vigor.11

Three liaison squadrons were assigned to the 3rd ACG—the 157th LS, 159th LS, and 160th LS. Both the 157th and 160th were activated at Brownwood AAF, Texas; the former was activated on February 10, and the latter was activated on April 1. The 159th came into being at Cox AAF, in Paris, Texas, on March 1. All three squadrons were redesignated as Liaison Squadrons, Commando on May 4 and assigned to the 3rd ACG. They began moving to Statesboro AAF in late May and were up and operating from their new field by the middle of June.

Upon their arrival at Statesboro, the squadrons found the 341st Airdrome Squadron, Commando awaiting them. The 341st had just been activated on May 18, and it would serve as the service organization for all three liaison squadrons. These units remained at Statesboro until mid-August, when they moved to Cross City AAF, Florida. A sense of urgency permeated the squadrons throughout the period. The men believed that movement overseas was imminent, and training was conducted with a high level of energy and purpose.12

The final piece that completed the 3rd ACG’s puzzle was the 237th Medical Dispensary, Aviation. Activated at Robins Field, Georgia, on March 15, 1944, it finally joined the group at Lakeland on July 6. Like its sister unit, the 236th with the 2nd ACG, the 237th would prove a valuable asset to the Air Commandos.13

When Olson arrived in June to assume command of the group, he quickly cleared up any uncertainty among his men concerning their mission and how he expected them to perform it. He described what the 1st ACG had done in Burma and explained that his group would probably be employed in a similar manner. Olson inherited a smoothly running group staff and made few changes. By mid-July, his staff comprised (among others) Lt. Col. Elmer W. Richardson, operations officer; Kalberer, executive officer; Maj. John H. Easley, flight surgeon; Capt. Clarence W. Thomas, intelligence; and Capt. Ulysses S. Aswell, chaplain. All the squadron commanders are listed in the accompanying table.14

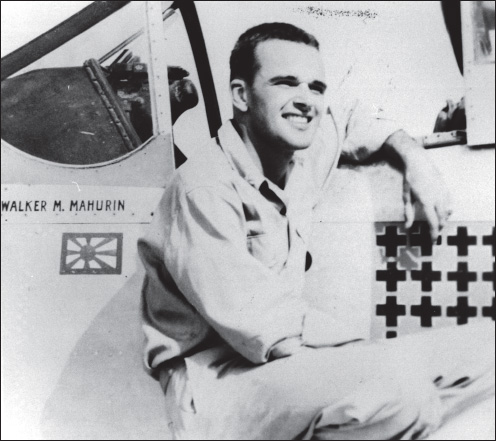

Olson was blessed with a number of veterans, including Richardson, an eight-plane ace in China, and 1st Lt. Louis E. Curdes, an eight-plane ace in Europe and the Mediterranean. Another individual of note assigned to the group was one “Rush” Russhon, the same man who took the critical pictures of Broadway for the 1st Air Commandos. He now was the 3rd ACG’s photographic officer and would later be its public relations officer. But the group’s best-known individual was probably the 3rd Fighter Squadron’s leader, Maj. Walker M. “Bud” Mahurin. Mahurin had flown with the famed 56th Fighter Group in Europe, where he had downed twenty-one German aircraft. When his twenty-first kill also fatally damaged his Thunderbolt on March 27, 1944, Mahurin had to take to the silk. Fortunately, he was able to contact members of the French Resistance, who got him back to England on May 7.15

3rd Air Commando Group August 1944

Lt. Col. Arvid E. Olson Jr.

3rd Fighter–Reconnaissance Squadron/3rd Fighter

Squadron, Commando

Maj. Walker M. Mahurin

4th Fighter–Reconnaissance Squadron/4th Fighter

Squadron, Commando

Maj. Steven H. Wilkerson

318th Troop Carrier Squadron, Commando

Capt. Charles C. Carter Jr.

157th Liaison Squadron, Commando

Capt. Clarence L. Odum

159th Liaison Squadron, Commando

Capt. Rush H. Limbaugh Jr.

1st. Lt. William G. Price III (October 25, 1944)

160th Liaison Squadron, Commando

Maj. John E. Satterstrom

334th Airdrome Squadron

Capt. Harmon V. Howe

335th Airdrome Squadron

Capt. Woodson S. Herring

341st Airdrome Squadron

Capt. Bertram E. Solomon

Capt. Floyd W. Fuller (September 21, 1944)

343rd Airdrome Squadron

Maj. Charles L. Foster

237th Medical Dispensary, Aviation

Maj. Milford N. Childs

Note: The dates in parentheses indicate when the officer began serving with the 3rd ACG.

Although Mahurin knew D-day was imminent and wanted to be in on that show, he was ordered back to the United States to make a few speeches for the War Bond drive and then to take a thirty-day leave. The speeches were excruciating to him, and though leave was pleasant when dealing with the public, he was itching to get back into combat. He heard that Alison was recruiting for some new ACGs, so he contacted his old friend to see if he could be of use. Regulations, however, prohibited fliers returned to the United States from going back into combat for one year. Alison said he would see about a job and also about getting Mahurin a waiver to return to combat if he wanted it. Mahurin soon received a telegram from USAAF Headquarters stating that if he waived the regulations for return to combat, a position as commanding officer of the 3rd ACG’s 3rd Fighter Squadron, Commando, was available. Within five minutes Mahurin had the waiver speeding back to Washington.16

Mahurin was a very aggressive fighter pilot, and he made quite an impression on the mostly young fliers. Lieutenant Vincent Krout, a pilot in the 4th Fighter Squadron, recalled Mahurin coming over occasionally in the Philippines to lead a flight from the 4th. “When he did,” Krout said, “I usually got assigned to fly his wing. And he was a maniac. When he got in the airplane, I think he shoved the throttle all the way to the firewall and left it there. He just flew like a crazy man, in my opinion. It was all you could do to keep up with him. Extremely difficult to fly with. I don’t know how he flew with his own squadron, but he could wear you out.”17

When the 3rd ACG’s fighter squadrons finally received their planes, it was a mixed bag of weary P-40s and P-51B/Cs that were well worn from many hours of use by countless fliers. Nonetheless, the pilots were happy to get anything to fly. Unfortunately, accidents happened during this period. Accidents were not uncommon throughout the USAAF in World War II because training was conducted at a hectic pace. There were midair collisions and landing accidents and mechanical failures of various sorts. Some of the pilots were able to get out of their crippled planes, some did not. There would be brief periods of mourning for fallen friends, and then the fliers returned to the job at hand. For time was running short.

In mid-August 3rd ACG headquarters and the fighter squadrons and their ADSs moved from Lakeland to Alachua AAF outside of Gainesville, Florida, to begin a series of important exercises involving the entire group. The liaison squadrons and their ADSs were located forty-five miles west of Gainesville at Cross City, while the 318th TCS and the 343rd ADS operated from Dunnellon, about fifty miles southwest of Gainesville. It was in the triangle formed by these airfields that the group generally held its exercises. The high point of this training was a combined field maneuver involving all the units. Group aircraft reconnoitered and photographed an “enemy” airfield, conducted simulated bombing and strafing attacks, and carried out a night glider assault. The assault troops had to hold out against an “enemy” force for a couple of days before being pulled out by night glider snatches. The exercise was deemed successful by the exercise umpires, and the men felt they were ready to take the next step—movement overseas and entry into combat.18

Observers from III Fighter Command, the 3rd ACGs parent organization, and USAAF Headquarters concurred with the Air Commandos’ assessment and, at long last, the group underwent its Preparation for Overseas Movement (POM) inspections. Even as these inspections were being made, the plans and timing on how to use the 3rd ACG were undergoing drastic changes. For months the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) had been debating whether the next advance across the Pacific should be aimed at the Philippines (specifically Luzon), at Formosa (a then-commonly used name for Taiwan) and the China coast, or at both targets. MacArthur pressed for the Philippines, while Admiral King, the chief of naval operations and commander of the U.S. fleet, argued just as forcefully for Formosa. In June, as the Marianas invasion was unfolding, the JCS were even considering bypassing both the Philippines and Formosa. Such a thought appalled MacArthur, who had pledged to return to the Philippines. He presented the JCS his latest plan—Reno V. In this plan, Sarangani Bay on Mindanao would be assaulted on October 25, 1944, followed by landings on Leyte about November 15, on southeastern Luzon in mid-January 1945, and in Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, on April 1, 1945.

If Reno V was accepted, however, the Formosa operation would have to be postponed until October 1945, and this King would never accept. MacArthur met with Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, CinC for Pacific Ocean Areas, and President Roosevelt at Pearl Harbor in late July to press his case. Following the conference MacArthur believed he had won support for going into the Philippines first, but Roosevelt (cagey politician that he was) never said that the Formosa operation was canceled, nor had he said which of the two options would come first.

Wrangling over the strategy for the forthcoming Pacific operations continued for the next couple of months. Then, in early September, the JCS approved MacArthur’s plan for landings at Sarangani Bay and set a target date of September 15. Further advances in the Philippines were set for December 20, with landings on Leyte in the Surigao area. Whether Luzon or Formosa would follow was left unspecified.

When Alison returned to the southwest Pacific, he was placed in charge of planning an airborne assault on Mindanao using gliders from both the 3rd ACG and other troop carrier units. This plan was scratched with spectacular suddenness in mid-September. Adm. William F. Halsey, whose Third Fleet was operating off the Philippines in support of the Peleliu and Morotai operations, came to the conclusion (based on the reports of his fliers) that the Japanese were weak in the Philippines. He recommended canceling the above two operations and, instead, striking directly at Leyte.

Although it was too late to call off the Peleliu and Morotai landings, Nimitz was willing to forego landings at Yap that were scheduled to occur at about the same time as the other invasions, and he offered MacArthur the use of the Army corps scheduled for Yap. As it turned out, Halsey was wrong; the Japanese were very strong in the Philippines, and fighting would be bloody before the islands were retaken. Nonetheless, a radical decision was made to invade the Philippines at Leyte on October 20 rather than at Mindanao on November 15. The Air Commandos would have been hard pressed to have been available by November 15. Now there was no way they could be used in the invasion of the Philippines.

The men of the 3rd ACG, naturally, knew nothing about such high-level planning. They just knew they were getting ready to go overseas, and the sooner the better. Following the POM inspections, most of the group proceeded to Drew Field in Tampa to begin processing for the overseas movement. The 318th TCS and the 343rd ADS returned to Camp MacKall for some brief training before going to Baer Air Field in Fort Wayne, Indiana, on their next step what seemed to be an interminable journey overseas. Deliverance from ennui and the anxiety of not knowing if they were heading into combat was finally at hand for the men of the group, however.

The 3rd ACG’s air echelons were the first to leave. The fighter pilots were flown by transports to Nadzab, New Guinea, where they picked up new P-51D Mustangs. The squadrons also picked up some replacement pilots. Most of these airmen had been in the southwest Pacific for a couple of months and had been ferrying P-40s between bases. None had any Mustang experience, but their checkout was simple. Given an airplane, they were told to fly it! The P-51 had a little quirk that caught many by surprise on their first flights. It was customary in the P-40 to slide its canopy back for landing. When the fliers did this in the P-51, dust and debris flew everywhere, momentarily blinding them. Even goggles could be ripped off. The windstorms caused no injuries, but pilots always landed with canopies closed afterward.19

The 318th TCS flew its own aircraft to New Guinea, leaving Baer on October 10. Their final stop in the United States was Fairfield AAF, near San Francisco. Final processing and the making up of some equipment shortages took three days, and then it was out over the Golden Gate to Hawaii. From Hawaii the C-47s headed for Christmas Island and then to Canton Island. The sixteen transports were split into two sections at Canton, one going by way of Tarawa and Guadalcanal, and the second going via Fiji, New Caledonia, and Guadalcanal. The last leg was to Nadzab, where the squadron touched down on October 26.

Upon their arrival, the men discovered that they had not been expected and that the local commander had decided, over the protests of the Air Commandos, to place the men and planes in a replacement pool. It was only the intervention of Olson, who appeared seemingly out of nowhere, that set matters straight. The 318th TCS was an integral part of the 3rd ACG, Olson told the other man, and it would be treated as a functioning unit.

Shortly afterwards the men and planes of the 318th began carrying cargo and passengers all over New Guinea and evacuating wounded to Australia. It was tough, demanding work, particularly since the squadron had few supplies and no maintenance men. The 3rd ACG ground crews were just then beginning their own trip to the combat zone. Nevertheless, in typical Air Commando spirit, the 318th’s pilots and crew chiefs kept their planes flying with remarkable efficiency.20

Meanwhile, back in the United States, Olson and Richardson and several other staff officers had disappeared from Florida on October 18. They would not be seen again by the Air Commandos, except for by pilots of the 318th, until they rejoined the group on Leyte. The group commanders were swiftly followed by the ground echelons. The units at Drew began leaving by train on October 24, while those at Baer left on the 27th. Both trains were headed for Camp Stoneman, which was north of Oakland on San Francisco Bay’s east side.

The group’s stay at Stoneman lasted only about a week, but the brief period was packed with last-minute activities, including drawing new uniforms and equipment, listening to more lectures, getting more shots, and filling out form after form. Most sobering of the latter were the insurance papers for next of kin and the wills, as those served to remind the men that where they were going would not be a picnic.

On the afternoon of November 6 the men boarded ferries for the short trip down the bay to their home for the next three weeks, the USS General M. L. Hersey. The transport was big and new, some 38,000 tons and making just her second voyage to the war zone. As big as she was, the Pacific was bigger, and for at least the first few days after their departure on the 7th, the Air Commandos noted that their ship rolled a lot. Attendance at meals was low for a time as many decided hanging over the rails was a better choice than being in a hot, crowded mess.

On November 16 the transport crossed the equator, and King Neptune came aboard to initiate the pollywogs into his realm. While outnumbered by the nautical neophytes, the shellbacks aboard the General M. L. Hersey more than held their own to administer the usual punishments to the pollywogs. Although many of the Air Commandos were aching the next day, they were full-fledged shellbacks and could look back on the previous day’s ceremonies with a certain amount of rueful grace. At least the beatings and such had broken the voyage’s monotony.

A brief stop was made at Guadalcanal, which had become a major logistics base. Then it was on to Finschafen and Hollandia on New Guinea. There was no time for the troops to disembark at any of these harbors, but they could get a close look at land after days of seeing nothing but water. On November 26 the General M. L. Hersey left Hollandia bound for her final destination, Leyte. The transport ship anchored off Leyte near the village of Palo on the 30th. Most of the night was spent preparing to go ashore, and finally around 8:00 AM, DUKWs (pronounced “ducks”) and landing craft began shuttling the Air Commandos to shore. The reception they received was not what they had anticipated. Apparently, their arrival, like that of the 318th TCS in New Guinea, had not been foreseen. “The group found itself orphans; unexpected, uninvited, and unwanted,” wrote the 159th LS’s historian.21 The 3rd Fighter Squadron’s historian concurred, noting, “It was hard to believe that the Commandos were unheard of. . . . We came to help but nobody seemed to give a particular damn.”22 To add insult to injury, a WAC detachment had landed a day earlier to much greater enthusiasm.

The men of the 3rd ACG also discovered that rain would be a constant companion over the next few weeks. Pup tents were pitched on the muddy ground but provided scant protection, as they just seemed to sink into the waterlogged ground as torrential rains pounded Leyte. Moving to a different spot and repitching the tents did no good. The group continued its semisubmerged existence for three days before someone higher up, out of pity or just wanting them off the crowded beachhead, directed a move a few miles down the beach to San Roque. Conditions were only slightly better there, but the group’s equipment, including cots, had begun to arrive, finally enabling the men to stay above the floods that gushed through the tents each night.

San Roque was a reasonably pleasant interlude, with some fine swimming offshore. The group was just getting established when a near disaster struck. A portion of the 3rd ACG’s bivouac was occupied by a fuel dump. A fire started in the dump on the evening of December 10, and barrels of gasoline began exploding and flying through the air. Little firefighting equipment was available, so the fire was allowed to burn itself out. Unfortunately, much of the group’s personal equipment was lost in the fire, and its men had to rely on the good-heartedness of others for some time before their equipment was replaced.23

December 15 saw the group receive surprise visitors in the persons of Olson and several of his staff. Olson was just as surprised as his men because the first he knew of their presence on Leyte was when he was on his way to V Fighter Command Headquarters and saw a sign proclaiming that one of the areas he passed belonged to the 3rd ACG. All concerned were happy to see each other again, and Olson assured his men that they would soon see action. Even as the reunion was taking place, the fighter pilots were getting acquainted with their new P-51Ds down in New Guinea, and they would soon arrive on Leyte.

In the meantime, the 3rd ACG’s status in Fifth Air Force was formalized. The Air Commandos were assigned to the V Fighter Command on December 13, and five days later they were further assigned to the 86th Fighter Wing.24

A few day after Olson’s arrival at Leyte, the group made yet another move, this time a couple of miles north of San Roque to the vicinity of Tanauan. There, an airfield paralleling the coast had been under construction since November 21, and it had just opened to traffic on December 16. The field had a 5,300-foot-long pierced steel plank runway, another 3,500 feet of taxiways, and ten hardstands. Further construction lasting into January lengthened the strip another 700 feet and added more taxiways and another forty-three hardstands.

Tanauan, however, had an interesting obstruction at its south end. Immediately to the south rose a rocky hill that was three hundred feet high. Naturally, this limited approaches from that direction. Approaches from the north, on the other hand, were over water, and there were no problems landing from that direction. No accidents were ever reported due to the hill.

It was at Tanauan that the 3rd ACG’s fighters would begin operations. This site was much nicer (and somewhat drier) than any so far. A lot of work other than airfield construction remained to turn the place into a fully functioning facility, though, and much of the rest of December was involved in those activities. Tanauan was not the only airfield available to the 3rd ACG. While waiting for the arrival of their planes, the men of the liaison squadrons and their ADSs built an airstrip using their hands and a single bulldozer. After it opened in January, the strip was dubbed “Mitchell Field,” after the 157th LS’s 2nd Lt. William Mitchell, who had led the construction effort.

The 3rd ACG’s commander, Col. Arvid Olson, at his headquarters, which had been established in a school in San Nicolas, Luzon. Note the dispatcher working in the open. (U.S. Army Air Forces archives)

Col. Walker M. “Bud” Mahurin poses with his suitably decorated fighter showing the twenty-one kills he had amassed in Europe and the one Japanese victory he obtained with the Air Commandos. (U.S. Army Air Forces archives)

A typical light plane strip bulldozed out of rice paddies: At least one of the parked L-5s is from the 3rd ACG’s 159th Liaison Squadron. (U.S. Army Air Forces archives)

First Lt. Louis E. Curdes’ Mustang sports a new victory symbol to go with his German and Italian kills. (U.S. Army Air Forces archives)

TSgt Vincent T. McNally chalks up another enemy aircraft on the group’s scoreboard at the 3rd ACG’s headquarters. (U.S. Army Air Forces archives)

Swamp Angel II taxies at Laoag for another mission. (Courtesy of the World War II Air Commando Association via Edward Young)

A wounded soldier is loaded into a 157th Liaison Squadron aircraft for evacuation to a hospital in the rear. (U.S. Army Air Forces archives)

A landing accident claimed this Mustang at Gabu. (Courtesy of the World War II Air Commando Association via Edward Young)

The liaison pilots, who had not flown in several months, visited the nearby 25th LS to see about borrowing some of their planes. The 25th was happy to see the Air Commandos and loaned them a couple of L-5s to keep up their flying proficiency and also to fly a variety of missions for the 25th LS.25

As 1944 ended and 1945 began, the men of the 3rd ACG were ready to assume their station among the combat-hardened units of the Fifth Air Force. That time was about to come.