New York City dog owners and the Park Enforcement Patrol are periodically at odds about whether dogs should be permitted to walk (or run) free. “When you give an inch, they take a lawn,” says Parks Commissioner Henry J. Stern, who keeps his golden retriever, Boomer, firmly leashed. But pressure groups like You Gotta Have Bark, in Prospect Park, and the Urban Canine Conservancy, in Central Park, have lobbied for greater access to the city’s wide-open spaces. “Let Rover rove!” is their battle cry. Plans are afoot to seek permission for a spacious dog run in Central Park’s Sheep Meadow, to be paid for by a dog-food company in exchange for “a tasteful bronze plaque.” Meanwhile, park rangers ticket the indignant scofflaws who contend (in the words of the Times reporter Douglas Martin) that “canine happiness is a greater good.”

The recent account in the Times of this controversy and a subsequent endorsement of “canine liberation” by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas unleashed a flood of responses. In a highly unusual allocation of space, the Times devoted its entire letters column to the topic, printing seventeen letters in all, under the urbane heading “Sunday in the Park with George, Rover and Spot.” Major elections, budget battles, and acts of God have had to make do with less. Dog owners wrote to complain that they alone were being singled out by park rangers (“Have you ever seen a skater get a ticket? A litterer? A graffiti artist or a kid doing damage?”), while a bird-watcher protested that loose dogs endanger the city’s “wild avifauna.” “Parks and other public places were created for all Americans, be they bare of behind or covered with wool, two-footed or four-footed,” one letter declared. “The latter have faithfully served our country alongside the former in war and peace, and therefore deserve to share fully in the freedom they helped to preserve.” Political hyperbole was, indeed, the order of the day. “Dog lovers of New York, unite!” Elizabeth Marshall Thomas exhorted. “You have nothing to lose but choke chains.”

Not content with vox populi, the paper itself weighed in with an editorial a few days later, conceding that “the dog owners do have emotion on their side” but supporting the city’s “rationality” in requiring leashes on pets, at least during prime time. (The Parks Department, in what the Times proudly called “a very New York–style accommodation,” had made it clear that it wouldn’t enforce the leash law before 9 A.M. or after 9 P.M.) Nor was this the last that readers heard on the subject: an Op-Ed piece a few days later lamented the supposed exclusivity of neighborhood dog runs, the fees they demanded, and the arcana of the application process. It was like getting your child into private school, only, if possible, more difficult.

To leash or not to leash: why is this question currently testing the limits of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? The answer, I think, has to do with the way the dog both does and doesn’t stand in for the human being. A. R. Gurney’s Off Broadway comedy Sylvia caught this note perfectly by casting a human actress in the part of a dog. Sylvia, “lost and abandoned” in Central Park, jumps into Greg’s lap and becomes the love of his life—much to the consternation of his human spouse. When the Times divided the controversy between “rationality” (health, safety, control) and “emotion” (“the dog owners do have emotion on their side”), the emotion in question was a kind of identification with the dog: “Who wants to contemplate the life of retrievers or Rottweilers condemned to go through life without ever running on their own?” The dog endures the same confinement as human city dwellers and yet remains capable of a joyful animality that human beings fear they have lost forever. It is this impossible extension of themselves that humans fight so passionately to preserve.

But why are the stakes so high in the dog wars today? How are things different from the way they were four decades ago, when Richard Nixon’s “Checkers speech” established him as an ideal all-American dad? (“The kids love the dog.”) Some people, of course, would like to return to the Checkers-Fala era in American family consensus-building. The Republican Bob Dole, emulating Nixon in a similarly awkward attempt at public intimacy, recently spoke out in praise of his wife and his schnauzer in an address before a group in Bakersfield, California: “I got a dog named Leader. I’m not certain they got a file on Leader.… We’ve had him checked by the vet but not by the F.B.I. or the White House. He may be suspect.”

Like Dole, many Americans now live with dogs instead of children. (“Children are for people who can’t have dogs,” a New York friend of mine remarked recently.) Canine hip-replacement has become, like juvenile orthodontia, a household medical expense, and dogs are attending preschool and therapy sessions. A summer camp in Maryland, run by Shady Spring Boarding Kennels, features dog-paddling, Frisbee, and hiking, a Bark-and-Ride camp bus, a spa offering haircuts and pedicures, and photographs of dogs in their bunks for the proud owners to take home. “People treat their dogs like their children,” the camp director, Charlotte Katz Shaffer, says. “They look for a kennel like they look for a pediatrician.” The child-centered world of the fifties, so nostalgically recalled by the likes of William Bennett, has become the dog-centered world of Homeward Bound, Beethoven, and Look Who’s Talking Now.

At a time when “universal” ideas and feelings are often compromised or undercut by group identities, the dog tale still has the power to move us. Paradoxically, the dog has become the repository of those model human properties which we have cynically ceased to find among human beings. On the evening news and in the morning paper, dog stories supply what used to be called “human interest.” There was the story of Lyric, for instance—the 911 dog, who dialled emergency services to save her mistress, and wound up the toast of Disneyland. Or the saga of Sheba, the mother dog in Florida who rescued her puppies after they were buried alive by a cruel human owner. His crime and her heroic single-motherhood were reliable feature stories, edging out mass killings in Bosnia and political infighting at home. Here, after all, were the family values we’d been looking for as a society—right under our noses.

Indeed, at a time of increasing human ambivalence about human heroes and the human capacity for “unconditional love,” dog heroes—and dog stories—are with us today more than ever. Near the entrance to Central Park at Fifth Avenue and Sixty-seventh Street stands the statue of Balto, the heroic sled dog who led a team bringing medicine to diphtheria-stricken Nome, Alaska, in the winter of 1925. Balto’s story recently became an animated feature film, joining such other big-screen fictional heroes as Lassie, Rin Tin Tin, Benji, and Fluke.

Yet the special capacity of the dog for incarnating idealized “human” qualities like fidelity and bravery (“all the Virtues of Man without his Vices,” wrote Lord Byron feelingly about his beloved Newfoundland, Boatswain) has long been the object of literary admiration. Indeed, it is as old as canonical literature itself. Homer memorably told of the loyalty of Odysseus’ old dog Argus, who waited two decades for his master to return, and then died content. In the Rieus’ translation:

There, full of vermin, lay Argus the hound. But directly he became aware of Odysseus’ presence, he wagged his tail and dropped his ears, though he lacked the strength now to come nearer to his master. Odysseus turned his eyes away, and … brushed away a tear.…. As for Argus, the black hand of Death descended on him the moment he caught sight of Odysseus—after twenty years.

Recent collections like Dog Music: Poetry About Dogs, edited by Joseph Duemer and Jim Simmerman and the charming Unleashed: Poems by Writers’ Dogs, edited by Amy Hempel and Jim Shepard, have joined the ranks of anthologies from the turn of the century: The Dog in British Poetry (1893), Praise of the Dog (1902), To Your Dog and to My Dog (1915), The Dog’s Book of Verse (1916). Dog Music is a collection of poetry by Elizabeth Bishop, James Merrill, John Updike, Richard Wilbur, and James Wright, among others. Just to read the titles of their poems is to see how much they are about the human condition, the capacity for human emotion and consciousness: Richard Jackson’s “About the Dogs of Dachau,” James Seay’s “My Dog and I Grow Fat,” Keith Wilson’s “The Dog Poisoner,” Joan Murray’s “The Black Dog: On Being a Poet,” and so on. “Nobody can tell me/The old dogs don’t know,” James Wright says quietly in “The Old Dog in the Ruins of the Graves at Arles.” In “Dog Under False Pretenses,” William Dickey wonders, about the dog he adopted after her first owner returned her, “Why was she given up?”

For the first three days I thought she was timorous, elderly, a quiet dog …

After all these years

I should recognize, when I see it, shock.

If literature is about love and loss, or loss and love, something about the world we live in today tends to make those feelings more accessible and more poignant when they center on a dog. Whether these poems are really about dogs or about people is a hard question, but that is, in a way, their point: to get to the person, go by way of the dog.

Canine tributes in prose abound, too, many of them published with the proceeds earmarked for canine charitable causes. There is the lavish and beautiful book entitled Dog People: Writers and Artists on Canine Companionship, edited by Michael J. Rosen, which includes contributions from Edward Albee, William Wegman, David Hockney, Susan Conant, Armistead Maupin, Jane Smiley, Daniel Pinkwater, Nancy Friday (“My Shih Tzu/My Self”), and a host of other dog-loving luminaries. Artists and writers seem to permit themselves an emotional latitude when speaking of their dogs which they might consider inappropriate, unseemly, or merely too private when referring to friends and lovers.

Identification as much as admiration seems to tie the owner to the dog. Consider The Dogs of Our Lives: Heartwarming Reminiscences of Canine Companions, compiled by Louise Goodyear Murray, with contributions by such dog-lovers as Steve Allen, William F. Buckley, Jr., Sally Jessy Raphael, and Norman Vincent Peale. Each writer tells a dog story to illuminate his or her own life. Thus the inspirational Dr. Peale, the author of The Power of Positive Thinking, tells of Barry, a German shepherd who travelled on his own from the boot of Italy back to his original family, in Bonn, Germany, and then asks, rhetorically, “If a dog will walk twelve hundred miles for one year to obtain his objective, why won’t a human being keep trying again, and again, and again? … People who truly try are people who accomplish things!” The child-centered Fred (Mr.) Rogers describes getting his dog Mitzi when he was little “as a present for taking some terrible-tasting medicine.” Roger Caras, the president of the A.S.P.C.A. and a longtime spokesman for the humane treatment of animals, tells of his adoption of Sirius, a two-year-old greyhound who was scheduled to die because he had stopped winning races. When they met, Sirius, belying his name, was smiling. (“He doesn’t have a home?” Caras asked a volunteer at the greyhound-rescue network. “Well, he does now.”) If those are stinging little tears you are surreptitiously wiping away, you are in good company: dog stories—especially dog-rescue (and, alas, dog-cruelty) stories—are perhaps our most reliable contemporary source of genuine, unforced altruistic emotion.

Sigmund Freud, who himself became, late in life, a devoted dog-lover, observed, “Dogs love their friends and bite their enemies, quite unlike people, who are incapable of pure love and always have to mix love and hate in their object relations.” This is a view that many have held. In his epitaph for Boatswain—by whose side the poet asked to be buried—Byron declared:

To mark a friend’s remains these stones arise;

I never knew but one—and here he lies.

Not for nothing is Fido the pet name of man’s best friend—and woman’s, too. Emily Dickinson found life without her beloved dog Carlo almost insupportable, writing to her friend and mentor Thomas Higginson a spare and eloquent missive:

Carlo died—

E. Dickinson

Would you instruct me now?

But if dogs are mourned they are also famous mourners. Emily Brontë’s mastiff, Keeper, followed her body to the grave, leading the funeral procession together with her father, as perhaps befitted a male survivor; Anne and Charlotte walked behind. Keeper joined the Brontë family in its pew while the service was read, then took up his station outside Emily’s empty bedroom, and howled. Greyfriars Bobby, a Skye terrier who sat by his master’s Edinburgh graveside for fourteen years, was immortalized by a Victorian fountain (and dogs’ watering hole). Bobby’s statue has become a major tourist attraction, vying for popularity with the local castle. Nor is this popularity simply a by-product of the Victorian fashion in mourning. In the twentieth century, Hachiko, an Akita who belonged to a professor at Tokyo University, became the Greyfriars Bobby of his era. It had been Hachiko’s custom to meet his master’s subway train every night, and after his master died, in 1925, Hachiko went to the station and waited faithfully each evening until his own death, in 1934. A statue of Hachiko, paid for by his admirers, now stands at the subway exit.

A more recent canine mourner seemed at times the most eloquent and straightforward witness in the O. J. Simpson trial. Nicole Brown Simpson’s own Akita became the focus of days of testimony centering on what the witness Pablo Fenjves referred to as the dog’s “plaintive wail,” which a reporter described as a “truly memorable phrase, one that simultaneously captures the sadness beneath the circus, undergirds the prosecution’s case and offers a morsel of poetry amid the cop talk, Californiaspeak and legalese.” The lead prosecutor Marcia Clark’s “eyes lit up,” according to Fenjves, when he first spoke of a “plaintive wail,” and prosecutors later insisted that he use those words in his testimony. “That’s a very important phrase,” Clark’s associate Cheri Lewis said. It was as if only the dog could tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

Of course, the behavior of some of these animals, if it were to be faithfully followed by human beings, would strike us as distinctly odd and perhaps psychologically unsound. It’s one thing for Hachiko to meet his master’s train for nine years; it’s another for a bereaved human being to do so. Get on with your life, we say, and we mean it. But we can demand—and receive—from dogs a highly gratifying devotion that we no longer feel comfortable about demanding from one another. In addition, these icons of absolute fidelity offer us a sense of scale. The dog, by being “superhuman” in realms like constancy and loyalty, gives us permission to temporize, vacillate, and even fail.

It’s worth noting that the first “humane society” began, in the eighteenth century, as an organization to benefit people, not animals. The dogs were the guards, not the guarded; the Royal Humane Society was founded in London in 1774 for the rescue of drowning persons. Thus a portrait entitled A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society, by the famed dog artist Edwin Landseer, pictures a placid and handsome Newfoundland lying on a pier by the water’s edge. (The Newfie, together with the mastiff, was the nineteenth century’s hero dog of choice.) Today’s humane societies, including some that date back more than a hundred years, are “societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals”; significantly, they were founded in both England and America shortly after the abolition of human slavery and involved many of the same activists.

There is something right about using the word “humane” to describe the impulse to protect animals. The mistreatment of defenseless dogs arouses in us profound emotions of empathy and outrage. All our own fears of betrayal and abandonment leap immediately to mind. Only the other evening, I saw a local news feature about two dogs, nicknamed by their rescuers Mama and Baby, who had been tied to a tree in a densely wooded area and left to die. The reporter herself was in manifest distress, and explained that Baby reminded her of her own beloved dog.

Whether leashed or unleashed in life, the dog roams at large in our cultural imagination. An abandoned dog can break our hearts in ways that human strays all too often no longer do. Yet, at the same time, the dog offers a kind of emotional and practical microclimate in which we can make manageable a host of problems that in other areas of life seem overwhelming or out of control: health insurance, day care, preschool, homelessness, depression, euthanasia. The president of the National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis has observed ruefully, “How ironic that we seem to care more about the happiness of animals than humans.”

But is it ironic? Or is it just another way of locating and pursuing human pleasures—like love—that seem increasingly hard to come by? As the market for pet products and services booms, the notion of spending so much time and money on dogs strikes many people as vain, as another way of “putting on the dog” by competing in ostentatious expense. No doubt the human comedy in the cavalcade of pet paraphernalia has as much to do with excesses of capitalism as with excesses of emotion. Why should it be more peculiar to have seven different kinds of dog leash than seven different kinds of Barbie doll? The fortunes of people and dogs have been linked for centuries, and if our own century has a sometimes risible way of showing as much, that is a sign of the century’s folly, not the dog-lover’s.

In the end, it is not substitution or anthropomorphism that produces the human love of dogs and the current preoccupation with them in our culture. The pathos of lost, unwanted, abandoned, neglected, or maltreated animals—from Homer’s loyal Argus to yesterday’s Mama and Baby—speaks, somehow, to the rootlessness and nostalgia inherent in the postmodern condition. Blessedly, dogs are free of irony and are strangers to cynicism (despite the etymology of the word—from the Greek kynikos, “dog-like”). In a relentlessly ironic age, their uncritical demeanor is perhaps just what we need. It is with dogs that, very often, we permit ourselves feelings of the deepest joy and the deepest sorrow. “Dogs are not our whole life,” Roger Caras writes in Dog People, “but they make our lives whole.” In this sense—so one could almost claim—it is the dog that makes us human.

Lassie used to come home every week, often having rescued Mom or Timmy from some scrape on the way. Now our welcome mats display two-dimensional collies—or Labradors, or Afghans (“available in fifteen breeds”)—and working dog owners call home to speak to their pets on the answering machine. Home is where the dog is. If the dog brings back the fifties in a miniaturized form, it’s because the dog is what we would like to have been to our parents: totally lovable, totally loved. The puppy represents what the yuppie fantasizes about childhood, what the older person fantasizes about youth, what the city-dweller fantasizes about the country, what the weary workaholic fantasizes about freedom, what the human spouse or partner fantasizes about spontaneity, emotional generosity, and togetherness. In soft-focus television commercials, and at the front door, the dog, leash patiently in mouth, is always waiting for you.

| 1996 |

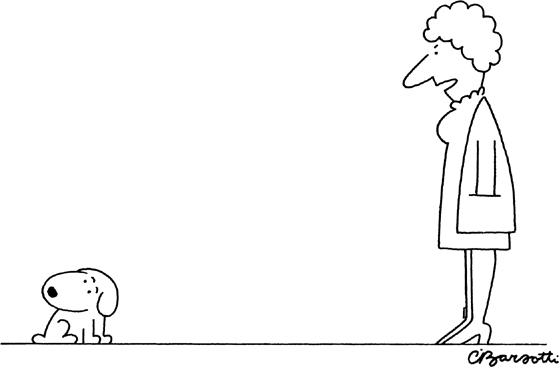

“Yes, I’m talking to you. I believe you’re the only Sparky in the house.”

IAN FRAZIER

Cycle Dog Food, a product of the Pet Foods Division of the General Foods Corporation, sponsored a K-9 Frisbee Disc Catch and Fetch Contest in the Central Park Sheep Meadow on a recent Saturday:

“You’re my sweet dog. You’re my sweet dog! Yes, you are. Yes … you … are! You want to wear a nice red bandanna around your neck, like that dog there and that dog there and that dog over there? Do you? You want me to wear a T-shirt with my picture and your picture on it, like that owner over there? Huh? You want your own fan club, like that dog named Morgan? You want your own cheering section, with people who cheer when you run after the Frisbee and who jump in the air when you jump in the air to catch the Frisbee? Maybe if you get to be National Champion Frisbee-Catcher, like that dog Ashley Whippet, you could be a Good-Will Ambassador for Cycle Dog Food, the way he is. Is that what you want? I know what you want. You want a Liv-A-Snap. You feel you’re not getting your proper Liv-A-Snappage. Here’s a nice Liv-A-Snap. Sit up. Here you—Whoa! Almost took my finger off. You certainly are insistent about getting proper Liv-A-Snappage. You want me to buy you some nice Cycle Dog Food? Now, I can’t buy you Cycle 1, because that’s ‘for a puppy’s special growing needs,’ and I can’t buy you Cycle 3, because that’s diet dog food, for overweight dogs, and I can’t buy you Cycle 4, because that’s for old dogs, so I guess I’d have to buy you Cycle 2—‘specially formulated for your dog’s active years.’ Are you in your active years? I should say so! If I threw you the Frisbee, would you show just how active your active years are? Would you run straight to the concession stand, like that basset hound? Would you knock over the man from Channel 4, like that half collie, half German shepherd? Would you run over and sniff that bush? Would you make me grab you by the tail and wrestle you to the ground before you gave back the Frisbee? Would you bounce in the air like a Super Ball, the way that poodle is doing? Would you stop running if I threw it too far, like that terrier? Would you discuss those pictures of the moons of Jupiter that Voyager 2 sent back? The ones with the erupting volcanoes? Huh? Would you? You are silent, but your eyes speak volumes. You’re my sweet dog! Yes, you are!”

| 1979 |