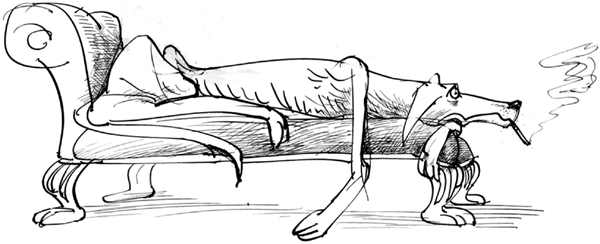

Four years ago, I was in a relationship that everyone who cared about me considered abusive. I was covered with bruises and scars. When my older son came home from college, he was greeted with a scene of loud, belligerent menace. My younger son, who still lived with us, tried to reach out, but more often than not his kindness was met by violence. My mother was terrified and refused to set foot in our house. In fact, no one came to visit us anymore. Nor were we welcome at anyone else’s house. Even a short walk on the street held the threat of an ugly brawl. At night, I lay in bed, felt the warmth of his body beside me, and tried not to move. I didn’t want to set him off. He was volatile, unpredictable. But I felt responsible for him. And, against all odds, I loved him.

He was not my husband, with whom I had just split up. Nor was he my boyfriend. (I had made one of those unforeseen middle-aged discoveries and was living with a woman.) My looming, destructive, desperate, and compelling companion was not even a human being. He was a dog. Or, as my friends and family pointed out, he was “just” a dog.

He appeared to be a lovely little dog, about two and a half years old, when we first saw him. It was a spring day, and he stood at the end of a long line of caged dogs in a Los Angeles pet-supply store, all strays to be adopted, all barking and yapping and hurling themselves against their wire enclosures. But he neither barked nor yapped. He stood politely, his head cocked expectantly. He wagged his tail in vigorous anticipation. When I picked him up, he squirmed with joy and lunged, ecstatic, licking my face, overwhelming me with a wave of urgent, instant love.

“Why do you want a dog?” my mother asked me. “I know why you want a dog. Because your son is going to college.” She looked at me pityingly. “When you went to college, I got a geranium.”

Buster, which is what we named him, was a seventeen-pound bowlegged mutt with a nondescript coat of short brown hair and a bulldog chest. His tail was far too long for his body, a dachshund’s tail. One ear stood up, the other flopped down. His face had the big, worried eyes of a Chihuahua, the anxious furrowed brow of a pug, and the markings of a German shepherd. He yodelled like a beagle and shook his toys with the neck-wrenching vigor of a pit bull terrier. A tough stray missing two toes on his left hind foot, he had been picked up in South L.A. and dumped in the city pound, where, we were told, larger dogs stole his food, until, the day before he was to be euthanized, he was saved by a private rescue group that tried to find a home for him. After we discovered Buster, a representative of the group came to our house to make sure it was safe for the dog. She neglected to tell us that the dog was not safe for us. Perhaps the rescuers were blinded by hope, since we had lifted the dog from his crate and hugged and kissed him with no ill effect. Perhaps they were confused. They had so many dogs to place in homes. Perhaps they were simply desperate.

I grew up reading books about heroic collies. It was from the novels of the popular writer Albert Payson Terhune, treasured by my father before me, that I learned the word “puttee.” Terhune would don a pair to walk through the grounds of Sunnybank. I also learned about “carrion,” in which his dogs would roll luxuriously, and a “veranda,” on which they would sit of an evening, curled contentedly at the feet of their god. Sunnybank was two generations and several classes and ethnic groups away from my world. Terhune, who in the books referred to himself as the Master, raised collies on a sprawling estate in northern New Jersey, which in his novels was called The Place. As impeccably bred as Sunnybank Lad, the Master claimed ancestors who had come to the New World from Holland and England in the seventeenth century. Terhune heatedly defended the rights of dogs and trees, but he was not a man of the people. There is a wonderful story by James Thurber describing the Master’s highborn rage (“like summer thunder”) when a Mr. Jacob R. Ellis and family, Midwestern tourists come to take a gander at Sunnybank in their Ford sedan, ran over the beloved champion Sunnybank Jean. And the Master’s disgust for Negroes and the “rich city dweller of sweatshop origin” was virulent and unashamed. But I noticed none of that as a child, for we had collies, too. Our patient, plodding dogs with their matted ruffs in no way resembled the grand animals of the novels, but they did follow my brother and me protectively around the neighborhood. Would they have leaped at the throat of an attacker, like Buff of “Buff: A Collie” or Lad in “The Juggernaut”? Would they have instinctively guided stolen sheep back into their proper herd? Or wandered for months, living on squirrels, looking for me, their only true Mistress? One of them took long walks every day with an inmate from the sanitarium just down the road. They herded children during recess at an elementary school nearby. They wandered for miles until someone from several towns away would check their tags and call us to come get them, at which point they would greet us with unalloyed, and unsurprised, joy. This was my background with dogs: they were in the background. Or they were in books.

Then one afternoon when I was eight, and unaccountably home alone, sitting in front of the Admiral TV with its big round knobs, watching The Mickey Mouse Club, my chin resting on my knees, Laurie, our small mahogany-colored collie, poked her nose in my face. I pushed her away. She whined and whimpered. I ignored her. She pushed my shoulder, hard. She licked my face, pushed again, barked, ran frantically to the door and back, whining, licking, nudging, until I tore myself away from the television and allowed myself to be herded through the kitchen and to the front door, where the dog planted her feet, barking and wagging her tail, until I understood. Smoke and flames were billowing from the bedroom hallway. Our squat little collie had saved my life.

Devotion to a dog like that is not hard for anyone to understand. But how do you explain your devotion to a dog who is not man’s best friend? Who is neither noble nor loyal? There is a popular training book called No Bad Dogs, but what happens when one is indeed bad and he belongs to you? What happens when bad dogs happen to good, or at least conscientious, people? When an animal defies kindness, defies the culture of therapy, and refuses to be redeemed?

On our very first evening with the little stray, we proudly placed his bowl of food on the kitchen floor. He rushed toward it, poking his muzzle eagerly into the organic human-grade kibble. We watched him, happy that we had rescued him from his hard, hungry life. There is something profoundly satisfying about taking in a creature no one else wants, a delicious flicker of moral superiority, and the surprisingly powerful pleasure of generosity. We watched our dog, a bit smug, perhaps, but, as I look back at the two of us, a new couple opening our lives to a needy dog, I feel only compassion. We had no idea what lay in store. Suddenly, Buster lifted his Chihuahua head. He jerked his pug face back toward his dachshund tail. He bared his pit-bull fangs, and—this all happened in seconds—savagely growling, as if another dog were threatening to move in on his meal, he lunged for his own tail, for his own flank, for his back foot. He whirled, a blur of snarling and slashing. It was a full-blown dogfight, the worst I had ever seen, and he was having it with himself.

That night, Buster jumped up on the bed, crawled under the covers, rested his head on the pillow like a little man, and fell asleep. Around three o’clock, I sat up, terrified. A deep angry roar swept over my face. It was Buster, his eyes rolling, pursuing something that wasn’t there. Sleeping with Buster, we soon discovered, was like sleeping with a Vietnam vet who suffers from post-traumatic-stress disorder. Demons haunted Buster’s sleep. The first time we left him alone in the house, we returned half an hour later to find him panting, foaming at the mouth, licking his new, self-inflicted wounds on a sofa covered with blood. And so, almost as soon as we got Buster, we began the quest to save him.

Over the next year and a half, we had Buster’s legs and spine and tail X-rayed; we had him tested for every conceivable kind of worm and fed him a hypo-allergenic diet of pure venison and sweet potatoes. We consulted a chiropractor and an acupuncturist. We took him to The BodyWorks with Veronica for Alexander technique and Feldenkrais. I searched the Internet for dog behaviorists and tried spray bottles of water and jars of noisy coins, clickers, herbal remedies, even aromatherapy. I typed “self-mutilation + dog” into Google, and articles in veterinary journals about paw licking and scratching came up. If only that were the problem, I thought. I typed in “Obsessive-compulsive disorder + dog” and consulted, by e-mail and phone, vets and animal behaviorists from all over the country. We watched Emergency Vets on Animal Planet, hoping we’d see some clue to Buster’s problems. We watched Animal Precinct, both heartened by and envious of all the bony, beaten, scarred, one-eyed dogs who caressed the hands of strangers and frolicked tenderly with babies when given half a chance. The only thing we didn’t try was a pet psychic. But sometimes, late at night, even that seemed plausible.

We couldn’t leave Buster at home, but when we took him with us in the car he threw himself against the window in an attempt to attack every bicycle, motorcycle, rollerblade, and shopping cart we passed. If it rained, he tried to subdue the windshield wipers. Parking-garage attendants pulled back when one of us handed them our ticket through the window while the other hung onto the snarling cur. When we fed Buster, we had to stand with a leg on either side, touching his flanks, to reassure him, we hoped, that no one was lurking behind his tail waiting to steal his food. But when, after a while, that, too, failed, and we began feeding Buster one piece of kibble at a time, he bit the hand that fed him. He bit the hand that groomed him. He bit the hand that petted him. After each attack, he would whimper and grovel, licking our faces. If you said, “Kisses” to Buster, he would hurl himself at you to lick your face. When you whistled, he sang along, yodelling comically. He was terrified of men, especially men with hats and, embarrassingly, black men, but he was also afraid of women and children, and he hated other dogs.

Buster slept splayed companionably across your torso if you lay on the couch reading. I thought he was beautiful. He had filled out. His chest was smooth and muscular, his coat shining. When he slept on me like that, momentarily calm, I was momentarily full of hope. One day, the young woman who lived next door reached in the car window to pet him, and he lunged at her, tearing a deep gash in her hand. She was unbelievably understanding, the wound did not require stitches, there was no lawsuit. But we were frantic, and ashamed.

A new vet told us he could tell by the dog’s teeth that he had had distemper when he was a puppy. Perhaps this had caused neurological damage. He couldn’t be sure. But he was sure about one thing. “Your dog bites,” the vet said. “Dogs that bite almost always continue to bite.” Then he said, “If this were my dog, I would put him to sleep.”

In the waiting room the day the vet told us to euthanize Buster, I saw an ad for a trainer in a local pet newsletter. Her name was Cinimon and she worked with rescued, hopeless, vicious pit bulls. We called her as soon as we got home.

Cinimon, a tan blonde with a pierced tongue, arrived with short-short cutoff jeans, an exposed midriff, and combat boots. She talked to us for hours, purposely ignoring Buster until he approached her, then handling him with incredible gentleness. She said we had to establish dominance over Buster now that he was in our pack. Her approach was not radical. We should put him in a crate at night and make him earn his treats by doing something, anything, even if it was as simple as sitting when told. Cinimon was full of hope and enthusiasm. I could not help seeing Cinimon, her delicious, oddly spelled name, and her own blooming California good health, as a promise of what Buster could hope for. The vet was probably right, but Buster would be the exception. Cinimon, a Valkyrie from the Valley, a girl with a household full of docile monsters, would make it so. Her training program was a reasonable behavior-modification approach. It made sense. To Cinimon. To us. Just not to Buster.

Buster was becoming a full-time job or, more precisely, a whole life. We went to bed at night worrying about him. Had he got enough exercise? Did exercise tire him out and calm him down, as it was supposed to, or did it hurt his damaged foot and stress his awkward anatomy? Would he sleep through the night, or would he wake and chase his demons and slash my calf in his confused fury? If we put him in his bed on the floor, would he fall asleep this time, or would he spin and spin and spin, tearing wildly at himself? We had an obligation to him. We had an obligation to innocent bystanders. Had we pursued every possible road to recovery? Did our umbrella insurance cover liability for dog bites? Should we put him to sleep?

In the morning, he would snuggle up and lay his head across my neck, snoring gently, his breath soft and sweet. He played in the morning, too, chasing toys and shaking them like dying rats. During the day, he snoozed, threw himself angrily against the glass doors to the front garden when the mailman walked by, threw himself angrily at his own back legs, at his long tail, at his deformed foot, at his good feet, at our feet. He sat when we told him to, looking up innocently. He was innocent: that was the most painful part. He was a vicious dog; even we would have to agree. He was destructive and dangerous, and if he had been a larger dog we would have had no choice but to put him down. But he was as innocent as a babe, baffled by his own behavior, terrified of everything that moved. He had been a lost dog. He was still a lost dog.

Then Cinimon suggested Prozac. In the months that followed, we consulted three vets, two psychopharmacologists, and a psychiatrist. We slapped peanut butter around Prozac, Buspar, Elavil, Effexor, Xanax, and Clomicalm, feeding the pills to Buster in a variety of doses and combinations. Even when they seemed to have some positive effect, it would last only a little while. Eventually, the violent behavior would return, worse than ever.

In September, we returned to New York. On the plane, the man in front of me tapped his headphones. Static? Up and down the aisle, people jiggled their headphones, wondering where the strange, ominous rumble came from. It came from under my seat, where a five-hour unilateral dogfight was taking place. At the airport, I put Buster’s case on the floor while we waited for the luggage. Someone screamed. I looked back. The case was whirling across the floor, unguided, an eerie missile of snarling desperation.

There are a million or so dogs in New York City. About thirty of them live on our block on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. We have a laundromat, two dry cleaners, two churches, two dentists, a senior center, a Malaysian restaurant, a Korean market, a bakery, and a store that sells cheap leather jackets. A homeless man of regular habits lives in the doorway of the Lutheran church. He does not have a dog. But the gay men who live in the brownstone next door with their five children have two beagles. A woman down the block has a West Highland terrier, a retired champion, whom she took in when the dog’s owner, a close friend, died suddenly, though she lives in one room and already had a shepherd mix named Tulip, after the heroine of J. R. Ackerley’s obsessively brilliant My Dog Tulip. There is an Afghan and an Italian greyhound with legs as spindly as pipe cleaners whose owner rides a bicycle to work. There is a blind miniature schnauzer who wobbles down the sidewalk without leash or supervision until, from a doorway, his owner hollers, “Henry!” and he totters home. There is a man who is in thrall to his young golden retriever; a three-legged yellow lab; two handsome young men with a Brussels griffon puppy; a man who lives with his mother and three tiny scruffy mutts; and a heavily tattooed window-washer with a racing bike whose shepherd mix just died. One woman who leans carefully on a cane and smiles beatifically from beneath pure-white hair gives gentle advice in a soft Irish brogue while Waldo, her Boston terrier, waits patiently, staring with his round bug eyes. And there is a woman with a warm and generous smile and a rich, cultured German accent who walks her aging Pekinese, Lord Byron, four times a day no matter how terrible the weather, a Holocaust survivor whose view of life is so beneficent I sometimes wait outside her building hoping she will materialize and provide wise counsel.

I don’t know the names of all our neighbors, but I know the names of their dogs. I do not go out to dinner or to the movies with the neighbors, as I do with my friends. I don’t make dates with them. I don’t have to. I know I will see one or two or more of them every day. The dogs on the block gambol happily toward a puddle of urine to sniff and amplify, then sniff and be sniffed, twisting until their leashes are laced like ribbons on a Maypole. Towering above them in choking humidity or cutting wind or hushed snow, the owners say hello, comment on the humidity or the wind or the snow, discuss the latest catastrophe in the city, admire each other’s animals, occasionally drop some highly personal remark about physical illness, a child, a parent, a divorce, nod sympathetically, and move on to scrape up a small, neat coil of excrement into an inside-out Fairway bag. New York City, on my block, is as small a town as Andy and Opie’s Mayberry. And it was Buster who introduced me to its citizens, lunging at saintly old ladies, storming wheelchairs and strollers, his hair bristling and his teeth bared. Everyone knew him. Everyone had advice. But, mostly, everyone had sympathy. When I saw Waldo or Lord Byron coming down the street, my heart beat faster and I felt tears of gratitude forming, for their owners, women who have seen hardship and evil, would reassure me that there was hope. With patience, they said softly, there was hope.

But Buster was not getting better. We contacted an animal behaviorist recommended to us by the New York Animal Hospital. He arrived with a Snoot Loop, a contraption he was marketing that was very similar to the better known Gentle Leader, a kind of bridle with a strap that tightens around the muzzle of a dog when he pulls. He charged us hundreds of dollars, the Snoot Loop cut into Buster’s nose, leaving a bloody welt, and the issue of self-mutilation was not addressed. My girlfriend, Janet, and I, outcasts everywhere but our one little block, began to argue about what to do, how to train Buster, what to feed him, when to feed him. Exhausted, discouraged, we resorted to the wisdom of our forebears, smacking the dog with a rolled-up newspaper when he attacked himself, or us. It was not effective.

One day, I took Buster to the dog run in Riverside Park near Eighty-second Street. We could let him loose there only when no other dogs were around. On this particular fall day, when the sky was a solemn gray and the leaves were dead on the ground around us, as brown as the dirt, I sat on a bench in the section reserved for small dogs and threw a hard red rubber ball for Buster. We had spent a disastrous Thanksgiving at my aunt’s house in Massachusetts. Buster had come with us. Whom could we have left him with? We were assigned a bedroom, and a large sign was taped to our door warning anyone who dared to enter not to let the dog exit. The day we left, we walked out of the room, loaded down with our bags and with Buster on his leash. We had been vigilant and tense for three days and had been rewarded with a Thanksgiving free of bloodshed. There was a great flurry of relieved family hugs and kisses, my two-year-old nephew waddled bumpily toward us, squealing, Buster lunged for him, leaped back with a mouthful of soggy diaper, whimpered while my nephew wailed, and we skulked off in disgrace.

Now I sat on the park bench and watched Buster. My sister-in-law and brother were barely speaking to me. My mother thought I was disturbed. My nephew was terrified of dogs. Janet and I were squabbling. My children were disgusted. Buster chased the ball happily, brought it back, waited until I threw it again, and again, just like a normal healthy dog. With his grinning face, one ear up and one flopped jauntily over his eye, his wriggling body and wagging tail, you would never know. That was one of the problems. People saw him and rushed over, cooing and crowing, hands stretched out to pet the adorable little dog. He would stiffen, growl, bare his teeth and lunge, all in a sickening second. When someone came within five feet, I would say something. At first, I struggled with the right wording. “He’s unpredictable,” I said. Or, “He’s afraid of strangers.” Sometimes, “He’s aggressive.” But all of these warnings seemed to leave an opportunity for people to test whether they might be the one special person he was not afraid of or aggressive toward, the unpredicted friend. Finally, I started saying, simply, “He bites.”

“He bites,” I said when a young woman came into the dog run with a bichon puppy, a cottony ball who bounced around her feet. Then I got up to leash Buster and take him away. But she put the bichon on her lap and told me not to worry about it. She was benevolent, awash with the joy of a merry new puppy. I thanked her. And then I felt it coming. I tried to stop myself, but I knew I was helpless. And, as I had done so many times before to so many unsuspecting strangers, I began to tell her the tale of Buster. I could hear the high note of panic, the rhythm of hysteria and desperation in my voice. I had heard something like it at playgrounds and bus stops from parents whose children threw sand or tantrums or took drugs or shoplifted or were flunking out of school. But the pitch, the speed of the chatter, the insistence on detail—I recognized that from somewhere else, from strangers approaching me on the street to tell me their life stories: from crazy people. I listened to myself and I heard a crazy woman.

Once again, a vet, this time our New York vet, told us to put the dog to sleep. “Your dog,” said Dr. Raclyn, a holistic practitioner who does not give up easily, “is deeply disturbed.” One evening when I brought Buster back into the building from his walk, I bumped into one of my neighbors, Virginia Hoffmann, a dog trainer. I blurted out that the dog was miserable, we were miserable, there was no hope. Virginia, who started out as an English teacher, became a trainer after having to deal with her own unhappy puppy. She had become more and more interested, more and more skilled, until one day she quit her day job. Here was someone, I thought, who could understand what we were going through. I asked her if she would help us. I wanted to give it one last try, to spend six months working seriously and consistently with Buster. He would never be sane, I recognized that. But maybe, just maybe, we could reduce the threshold of his suffering to make it bearable for him, and for us. Virginia took pity on us and agreed. She wanted to help us, she said, to help Buster, and she would learn from the experience. But she was very clear about one thing. She offered no guarantees.

“I found a trainer for Buster,” I said to my mother.

“Who? Clyde Beatty?”

Trim and neat, straightforward and calm, Virginia had a soothing effect on me. Perhaps she would on Buster, too. I had already considered another dog trainer who lived on the block. He had written several books and had a Catskill-comedian spiel that I found very engaging. His fee was so high that I tried one of his books first and discovered that his system required throwing things at your dog, to which approach Buster responded by attacking the suggested keys or wallet or paperback book that was launched at him, and then cowering in confusion. Another dog trainer I once ran into on the East Side told me she knew just what to do: lift Buster by the back legs and whack him across the jaw hard enough so it rattled. Then she gave me her card and walked on. I gratefully turned to Virginia, with her soft, firm voice and endless sympathy. She came three or four times a week.

Janet was in L.A. a lot then, and my day was centered on the dog. I approached him with a glove attached to a wooden spoon, rewarding him when he didn’t bite it. I used toys as a reward instead of food. I let him carry his toys in his mouth when we went outside, on the theory that he would be hard-pressed to bite with his mouth full. He learned the commands “touch” and “leave it.” I taught him to go to his bed, to stay, to heel, to jump through a yellow hula hoop. Clyde Beatty, indeed. All of this training had a goal—to give the dog something better to think about than his own fear. To give him confidence. To give him a better sense of his own deformed body. And to give us authority and control. I learned how to break up each task into tiny parts. We tried to get him used to wearing a muzzle, which he hated and would trigger one of his fits, by leaving it on for seconds at a time and rewarding him with a squirt of Cheese Whiz. I wished I had employed Virginia to help in child rearing. For, in addition to training, she taught me not simply to impose or demand but to observe. Virginia suggested that I keep a journal, noting the frequency and intensity of Buster’s fits: the details of his misery. Which side of himself did he attack? What might have provoked it? A noise? A touch? A smell? I timed the violent fits. I noted the weather, the time of the day, his position. How long since he’d eaten? Drunk? And then I made him come to me, or stay sitting as I walked away, or jump through a hoop. Buster was a wonderful pupil, smart and willing and obedient. He was an exceptionally well-trained mad dog.

I couldn’t wait until Virginia arrived for a lesson. When she walked through the door, my real day began. She brought me articles from veterinary behavioral journals. She relayed relevant anecdotes from friends and colleagues. I loved meeting Buster’s big, alert dark eyes and recognizing a quick, happy understanding. Buster bit Virginia on the first visit. I had my Buster kit of butterfly bandages and Neosporin handy. Though he seemed to sense that here was someone sent to help him, he could never tolerate more than about twenty minutes of work. So the rest of the time we went over the behavior charts like sailors checking the stars.

Janet and I began going out only to places where we could take Buster with us, eating at outdoor cafés in the rain and the bitter wind. But then Buster bit the waiter at Señor Swanky’s, and we stopped. We resorted to placing a large plastic collar shaped like an ice-cream cone around his neck when we left him alone. Used by vets to keep dogs from licking their wounds, the plastic cone worked more like blinkers for Buster: he was unable to see, much less bite, his hindquarters. One night, when I had brought Buster to my mother’s house in Connecticut (tolerated out of motherly pity and because it was the only way she would get to see me), I put him in his collar and went to visit an old friend. Ten minutes later, my cell phone rang.

“I’m locked in my room with the door closed,” my mother said. “Your dog is in the living room having a fit.” She sounded terrified.

When I got home, the dog was a blur of foam and fur. I ended up wrapping him in a blanket, the only way I could get near him without being bitten, and holding him on my chest in bed for four hours, trying to soothe him while he panted and trembled. I held him and I cried.

We could no longer leave Buster in his Elizabethan collar. He had another episode that required the blanket wrapped around him, the hours of trembling and rolling eyes. Virginia pointed me to an experiment that had been done with autistic children, in which they were wrapped tightly to help them regain awareness of their own bodies. She found an unlikely product called Anxiety Wrap, a suit for dogs, which worked on the same principle. She said that really the next step would be contacting a research veterinary school and handing Buster over for brain scans and further study. “Would you be doing that for his sake?” she asked. “Or your own? That’s always the hard question.”

It was a good question. Buster had become an intellectual puzzle, a challenge I could not let go of. He was my companion, certainly. The intensity of his need made the bond between us urgent and powerful. And I felt a responsibility, it was true. You cannot throw away an animal because he is sick. But there was also a little pool of vanity involved, and that insistent, stubborn optimism, a cultural trait, I suppose, that demands constant improvement. I would save this dog because, in a just world, I ought to be able to save him. It was a kind of humanitarian hubris. My dog was miserable. I insisted he get better.

We euthanized Buster eighteen months after we’d got him. We petted him as he stood on the vet’s stainless-steel examining table. He wagged his tail and licked our hands. After giving him an IV dose of Valium, Dr. Raclyn added sodium pentobarbitol. Buster turned on him with one last snarl, looked back at us, wagged his tail again, crumpled into our arms, and was gone.

It took six months before we had either the heart or the courage to do it, but we decided to get another dog, a puppy this time. We searched Internet rescue sites and visited the A.S.P. C.A., the city pound, and the North Shore Animal League. There were enormous, sad-eyed shepherd mixes and venerable poodle mixes and hopeful bull-terrier mixes. Lab mixes leaped and whippet mixes shivered. We should have taken them all. We should have taken every puppy, too, although their fat, gigantic paws foretold their gigantic futures. What we couldn’t find was a puppy who would stay small enough for our bicoastal commute. Sometimes we took Virginia with us to guide us, to protect us from falling under the spell of another charismatic but impossible dog. All the best, sweetest dogs we know are rescued dogs; nevertheless—a little guiltily, a little nervously—we drove to Frederick, Maryland, and picked up a tiny ten-week-old Cairn terrier. We named him Hector. A few months later, on the coldest morning of the coldest winter in decades, I took Hector to Central Park. There was smooth, slick snow on the ground. We made our way to Hearnshead Rock, a scenic jog of boulders rolling out into the lake. In spring, deep-yellow irises rise up there. In winter, the cove lets ducks and swans escape the wind. On this dark, achingly cold morning, the lake was almost completely frozen. The silver ice and the silver sky were cut in two by the skyline, and only in the crook of the rocks, where hundreds of ducks swam in circles, had the gray water been prevented from freezing. There were buffleheads and scoters and coots and even a wood duck. There was a great blue heron standing, not a foot from shore, as still as the black trees. The dog and I had been watching this tableau for twenty minutes or so when suddenly the heron shot his head into the shallow water, then snapped his neck back into its looping posture, a large fish dangling from his beak. He swallowed it. We watched the fish, a protrusion inching slowly down the bird’s elegant throat, and then we walked home through silent woods, catching each other’s eye now and then, checking in, companionable and intimate, sharing the exhilarating quiet. Hector, trotting beside me in the snow, was, like Buster, just a dog. And if, at that moment, I didn’t know exactly how to explain why people want to own dogs, with all the inconvenience and heartache attached, I felt that here, at least, was a clue.

Hector prances along the street Buster skulked, greeting neighbors and strangers and men in hats and toddlers in snowsuits. He loves everyone and everyone loves him. I often think of Buster, and it breaks my heart. People say, “You did everything you could.” But did we? What about Phenobarbital, even though every vet recommended against it? What about the autism suit? We should have moved to the country or sent him to the man in San Diego who leads a pack of dogs through the hills. What about the pet psychic? Then Hector pounces on an empty forty-ounce Budweiser can, almost as big as he is, and carries it proudly home. He kisses babies like a politician. He comes in peace.

| 2004 |

ALEXANDRA FULLER

In the early nineties, it was possible to walk along the Zambian side of the upper Zambezi River without seeing many people—just a couple of fishermen, children out hunting for rats, or women in search of mopane worms. On the Zimbabwean side, blond savanna reached extravagantly into the distance and elephants often ventured out from the shelter of the bush to drink. Zambia, however, was considerably poorer than Zimbabwe in those days; anything remotely edible on our shore was quickly harvested, and large animals were scarce. Traditionally, ordinary people would not have eaten certain animals—hippos, for example—but a long ache of hunger had eroded the luxury of cultural norms and now nothing was exempt from culinary consideration.

An elderly Belgian aristocrat (unstitched from the wealth of her family by wars and bad luck) owned land here, where the river quickened into rapids as it made its way toward the waterfalls the locals called Mosi-oa-Tunya, “the smoke that thunders.” Madame was a refugee of colonialism, remaindered from Zaire, but too possessed by Africa to return to Europe. She lived with several untrustworthy servants and a ragtag menagerie of peacocks, monkeys, dogs, cats, ducks, geese, chickens, and parrots.

My husband, Charlie, and I rented the cottage at the end of Madame’s plot. There was only sporadic electricity and no running water—inconveniences that we happily overlooked in our excitement at finding ourselves beyond the reaches of the nearest town. Livingstone, at that time, was a noisy, disgruntled place. A riot had recently broken out in a textile factory and the Indian owners had been badly beaten up. Indians—the only community that seemed to thrive in difficult economic times—were universally mistrusted by their jealous Zambian neighbors.

While Charlie left each morning to run boat trips below Victoria Falls, I stayed in the cottage with our infant daughter and a mixed-breed dog called Liz. Madame quickly established the parameters of her relationship with me—we were to be cordial but formal—visiting each other by written invitation only. Ours was a friendship born of a mutual antipathy for society (we both preferred animals), and we gradually developed a genuine fondness for each other.

Then Liz killed a duck (she was caught in the act by Madame, her mouth lined with bloody feathers). Clough, Madame’s gardener, brought over a brusque note on the afternoon of the murder, along with an invoice. Embarrassed, I sent cash and an apology by return post. Liz was confined to the barracks, except at night when she slept with us outside, where we had moved our bed to take advantage of the river breeze.

The following week, Liz allegedly killed a few more ducks and a half-dozen chickens. Madame, faced with such grave losses, came to see me without a letter of warning. The dog had acquired a taste for her livestock, she declared. I was responsible for “damages.” Clough wrung his hands, and I knew, without a doubt, who was responsible for the killing spree. But Madame was scrupulously loyal to all her servants. To speak against them, I knew, was to speak against Madame herself! So I paid up with more apologies and a promise to keep Liz with me at all times.

When a peacock was killed several nights later—sent plummeting from its roost in a paperbark tree—I finally summoned up the courage to protest. “But, Madame,” I said, “Liz could hardly have climbed all the way up there to kill a peacock.”

“Clough found the body,” Madame insisted. “He has taken it to be buried.”

“Cooked, you mean,” I muttered.

“Pardon?”

“Nothing,” I said, counting out kwacha notes from my dwindling household budget.

Another peacock and two peahens met their deaths before I confronted Clough: “I know you’re eating them.”

“No.” Clough mustered a look of indignation.

“It wasn’t Liz.”

“I am not the one. We can’t eat peacocks. They are”—he searched for an excuse—“taboo for us.”

“How can they be taboo? They aren’t even native to this country. They’re from India. How can something from India be taboo to you? Taboo means it must be something from your own culture.”

Clough’s face cleared. “Exactly. In our culture, we Zambians hate Indians. They are even worse than you. We wouldn’t eat something of their country.”

But the carnage stopped after that and my friendship with Madame survived, although very little else did. Eventually, Liz was killed by baboons, Madame sold the farm as a tourist camp, and we left Zambia for the less colorful comforts of the States.

| 2006 |