In the case of Sugar v. Forman, Cesar Millan knew none of the facts before arriving at the scene of the crime. That is the way Cesar prefers it. His job was to reconcile Forman with Sugar, and, since Sugar was a good deal less adept in making her case than Forman, whatever he learned beforehand might bias him in favor of the aggrieved party.

The Forman residence was in a trailer park in Mission Hills, just north of Los Angeles. Dark wood panelling, leather couches, deep-pile carpeting. The air-conditioning was on, even though it was one of those ridiculously pristine Southern California days. Lynda Forman was in her sixties, possibly older, a handsome woman with a winning sense of humor. Her husband, Ray, was in a wheelchair, and looked vaguely ex-military. Cesar sat across from them, in black jeans and a blue shirt, his posture characteristically perfect.

“So how can I help?” he said.

“You can help our monster turn into a sweet, lovable dog,” Lynda replied. It was clear that she had been thinking about how to describe Sugar to Cesar for a long time. “She’s ninety percent bad, ten percent the love.… She sleeps with us at night. She cuddles.” Sugar meant a lot to Lynda. “But she grabs anything in sight that she can get, and tries to destroy it. My husband is disabled, and she destroys his room. She tears clothes. She’s torn our carpet. She bothers my grandchildren. If I open the door, she will run.” Lynda pushed back her sleeves and exposed her forearms. They were covered in so many bites and scratches and scars and scabs that it was as if she had been tortured. “But I love her. What can I say?”

Cesar looked at her arms and blinked: “Wow.”

Cesar is not a tall man. He is built like a soccer player. He is in his mid-thirties, and has large, wide eyes, olive skin, and white teeth. He crawled across the border from Mexico fourteen years ago, but his English is exceptional, except when he gets excited and starts dropping his articles—which almost never happens, because he rarely gets excited. He saw the arms and he said, “Wow,” but it was a “wow” in the same calm tone of voice as “So how can I help?”

Cesar began to ask questions. Did Sugar urinate in the house? She did. She had a particularly destructive relationship with newspapers, television remotes, and plastic cups. Cesar asked about walks. Did Sugar travel, or did she track—and when he said “track” he did an astonishing impersonation of a dog sniffing. Sugar tracked. What about discipline?

“Sometimes I put her in a crate,” Lynda said. “And it’s only for a fifteen-minute period. Then she lays down and she’s fine. I don’t know how to give discipline. Ask my kids.”

“Did your parents discipline you?”

“I didn’t need discipline. I was perfect.”

“So you had no rules.… What about using physical touch with Sugar?”

“I have used it. It bothers me.”

“What about the bites?”

“I can see it in the head. She gives me that look.”

“She’s reminding you who rules the roost.”

“Then she will lick me for half an hour where she has bit me.”

“She’s not apologizing. Dogs lick each other’s wounds to heal the pack, you know.”

Lynda looked a little lost. “I thought she was saying sorry.”

“If she was sorry,” Cesar said, softly, “she wouldn’t do it in the first place.”

It was time for the defendant. Lynda’s granddaughter, Carly, came in, holding a beagle as if it were a baby. Sugar was cute, but she had a mean, feral look in her eyes. Carly put Sugar on the carpet, and Sugar swaggered over to Cesar, sniffing his shoes. In front of her, Cesar placed a newspaper, a plastic cup, and a television remote.

Sugar grabbed the newspaper. Cesar snatched it back. Sugar picked up the newspaper again. She jumped on the couch. Cesar took his hand and “bit” Sugar on the shoulder, firmly and calmly. “My hand is the mouth,” he explained. “My fingers are the teeth.” Sugar jumped down. Cesar stood, and firmly and fluidly held Sugar down for an instant. Sugar struggled, briefly, then relaxed. Cesar backed off Sugar lunged at the remote. Cesar looked at her and said, simply and briefly, “Sh-h-h.” Sugar hesitated. She went for the plastic cup. Cesar said, “Sh-h-h.” She dropped it. Cesar motioned for Lynda to bring a jar of treats into the room. He placed it in the middle of the floor and hovered over it. Sugar looked at the treats and then at Cesar. She began sniffing, inching closer, but an invisible boundary now stood between her and the prize. She circled and circled but never came closer than three feet. She looked as if she were about to jump on the couch. Cesar shifted his weight, and blocked her. He took a step toward her. She backed up, head lowered, into the furthest corner of the room. She sank down on her haunches, then placed her head flat on the ground. Cesar took the treats, the remote, the plastic cup, and the newspaper and placed them inches from her lowered nose. Sugar, the one-time terror of Mission Hills, closed her eyes in surrender.

“She has no rules in the outside world, no boundaries,” Cesar said, finally. “You practice exercise and affection. But you’re not practicing exercise, discipline, and affection. When we love someone, we fulfill everything about them. That’s loving. And you’re not loving your dog.” He stood up. He looked around. “Let’s go for a walk.”

Lynda staggered into the kitchen. In five minutes, her monster had turned into an angel.

“Unbelievable,” she said.

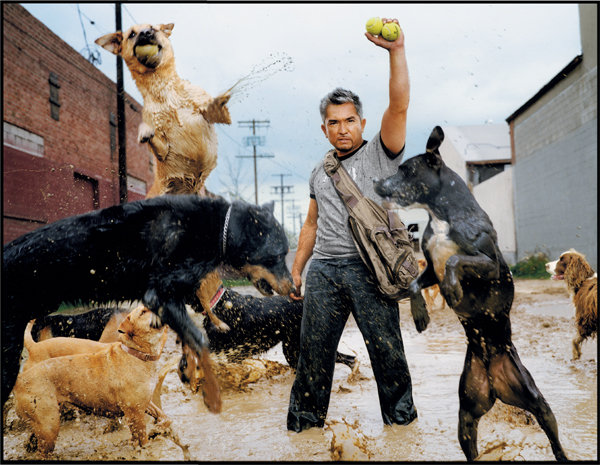

Cesar Millan runs the Dog Psychology Center out of a converted auto mechanic’s shop in the industrial zone of South-Central Los Angeles. The center is situated at the end of a long narrow alley, off a busy street lined with bleak warehouses and garages. Behind a high green chain-link fence is a large concrete yard, and everywhere around the yard there are dogs. Dogs basking in the sun. Dogs splashing in a pool. Dogs lying on picnic tables. Cesar takes in people’s problem dogs; he keeps them for a minimum of two weeks, integrating them into the pack. He has no formal training. He learned what he knows growing up in Mexico on his grandfather’s farm in Sinaloa. As a child, he was called el Perrero, “the dog boy,” watching and studying until he felt that he could put himself inside the mind of a dog. In the mornings, Cesar takes the pack on a four-hour walk in the Santa Monica mountains: Cesar in front, the dogs behind him; the pit bulls and the Rottweilers and the German shepherds with backpacks, so that when the little dogs get tired Cesar can load them up on the big dogs’ backs. Then they come back and eat. Exercise, then food. Work, then reward.

“I have forty-seven dogs right now,” Cesar said. He opened the eyedoor, and they came running over, a jumble of dogs, big and small. Cesar pointed to a bloodhound. “He was aggressive with humans, really aggressive,” he said. In a corner of the compound, a Wheaton terrier had just been given a bath. “She’s stayed here six months because she could not trust men,” Cesar explained. “She was beat up severely.” He idly scratched a big German shepherd. “My girlfriend here, Beauty. If you were to see the relationship between her and her owner.” He shook his head. “A very sick relationship. A Fatal Attraction kind of thing. Beauty sees her and she starts scratching her and biting her, and the owner is, like, ‘I love you, too.’ That one killed a dog. That one killed a dog, too. Those two guys came from New Orleans. They attacked humans. That pit bull over there with a tennis ball killed a Labrador in Beverly Hills. And look at this one—one eye. Lost the eye in a dogfight. But look at him now.” Now he was nuzzling a French bulldog. He was happy—and so was the Labrador killer from Beverly Hills, who was stretched out in the sun, and so was the aggressive-toward-humans bloodhound, who was lingering by a picnic table with his tongue hanging out. Cesar stood in the midst of all the dogs, his back straight and his shoulders square. It was a prison yard. But it was the most peaceful prison yard in all of California. “The whole point is that everybody has to stay calm, submissive, no matter what,” he said. “What you are witnessing right now is a group of dogs who all have the same state of mind.”

Cesar Millan is the host of Dog Whisperer, on the National Geographic television channel. In every episode, he arrives amid canine chaos and leaves behind peace. He is the teacher we all had in grade school who could walk into a classroom filled with rambunctious kids and get everyone to calm down and behave. But what did that teacher have? If you’d asked us back then, we might have said that we behaved for Mr. Exley because Mr. Exley had lots of rules and was really strict. But the truth is that we behaved for Mr. DeBock as well, and he wasn’t strict at all. What we really mean is that both of them had that indefinable thing called presence—and if you are going to teach a classroom full of headstrong ten-year-olds, or run a company, or command an army, or walk into a trailer home in Mission Hills where a beagle named Sugar is terrorizing its owners, you have to have presence or you’re lost.

Behind the Dog Psychology Center, between the back fence and the walls of the adjoining buildings, Cesar has built a dog run—a stretch of grass and dirt as long as a city block. “This is our Chuck E. Cheese,” Cesar said. The dogs saw Cesar approaching the back gate, and they ran, expectantly, toward him, piling through the narrow door in a hodgepodge of whiskers and wagging tails. Cesar had a bag over his shoulder, filled with tennis balls, and a long orange plastic ball scoop in his right hand. He reached into the bag with the scoop, grabbed a tennis ball, and flung it in a smooth practiced motion off the wall of an adjoining warehouse. A dozen dogs set off in ragged pursuit. Cesar wheeled and threw another ball, in the opposite direction, and then a third, and then a fourth, until there were so many balls in the air and on the ground that the pack had turned into a yelping, howling, leaping, charging frenzy. Woof. Woof, woof, woof. Woof. “The game should be played five or ten minutes, maybe fifteen minutes,” Cesar said. “You begin. You end. And you don’t ask, ‘Please stop.’ You demand that it stop.” With that, Cesar gathered himself, stood stock still, and let out a short whistle: not a casual whistle but a whistle of authority. Suddenly, there was absolute quiet. All forty-seven dogs stopped charging and jumping and stood as still as Cesar, their heads erect, eyes trained on their ringleader. Cesar nodded, almost imperceptibly, toward the enclosure, and all forty-seven dogs turned and filed happily back through the gate.

Last fall, Cesar filmed an episode of Dog Whisperer at the Los Angeles home of a couple named Patrice and Scott. They had a Korean jindo named JonBee, a stray that they had found and adopted. Outside, and on walks, JonBee was well behaved and affectionate. Inside the house, he was a terror, turning viciously on Scott whenever he tried to get the dog to submit.

“Help us tame the wild beast,” Scott says to Cesar. “We’ve had two trainers come out, one of whom was doing this domination thing, where he would put JonBee on his back and would hold him until he submits. It went on for a good twenty minutes. This dog never let up. But, as soon as he let go, JonBee bit him four times.… The guy was bleeding, both hands and his arms. I had another trainer come out, too, and they said, ‘You’ve got to get rid of this dog.’ ”

Cesar goes outside to meet JonBee. He walks down a few steps to the back yard. Cesar crouches down next to the dog. “The owner was a little concerned about me coming here by myself,” he says. “To tell you the truth, I feel more comfortable with aggressive dogs than insecure dogs, or fearful dogs, or panicky dogs. These are actually the guys who put me on the map.” JonBee comes up and sniffs him. Cesar puts a leash on him. JonBee eyes Cesar nervously and starts to poke around.

Cesar then walks JonBee into the living room. Scott puts a muzzle on him. Cesar tries to get the dog to lie on its side—and all hell breaks loose. JonBee turns and snaps and squirms and spins and jumps and lunges and struggles. His muzzle falls off. He bites Cesar. He twists his body up into the air, in a cold, vicious fury. The struggle between the two goes on and on. Patrice covers her face. Cesar asks her to leave the room. He is standing up, leash extended. He looks like a wrangler, taming a particularly ornery rattlesnake. Sweat is streaming down his face. Finally, Cesar gets the dog to sit, then to lie down, and then, somehow, to lie on its side. JonBee slumps, defeated. Cesar massages JonBee’s stomach. “That’s all we wanted,” he says.

What happened between Cesar and JonBee? One explanation is that they had a fight, alpha male versus alpha male. But fights don’t come out of nowhere. JonBee was clearly reacting to something in Cesar. Before he fought, he sniffed and explored and watched Cesar—the last of which is most important, because everything we know about dogs suggests that, in a way that is true of almost no other animals, dogs are students of human movement.

The anthropologist Brian Hare has done experiments with dogs, for example, where he puts a piece of food under one of two cups, placed several feet apart. The dog knows that there is food to be had, but has no idea which of the cups holds the prize. Then Hare points at the right cup, taps on it, looks directly at it. What happens? The dog goes to the right cup virtually every time. Yet when Hare did the same experiment with chimpanzees—an animal that shares 98.6 percent of our genes—the chimps couldn’t get it right. A dog will look at you for help, and a chimp won’t.

“Primates are very good at using the cues of the same species,” Hare explained. “So if we were able to do a similar game, and it was a chimp or another primate giving a social cue, they might do better. But they are not good at using human cues when you are trying to cooperate with them. They don’t get it: ‘Why would you ever tell me where the food is?’ The key specialization of dogs, though, is that dogs pay attention to humans, when humans are doing something very human, which is sharing information about something that someone else might actually want.” Dogs aren’t smarter than chimps; they just have a different attitude toward people. “Dogs are really interested in humans,” Hare went on. “Interested to the point of obsession. To a dog, you are a giant walking tennis ball.”

A dog cares, deeply, which way your body is leaning. Forward or backward? Forward can be seen as aggressive; backward—even a quarter of an inch—means nonthreatening. It means you’ve relinquished what ethologists call an “intention movement” to proceed forward. Cock your head, even slightly, to the side, and a dog is disarmed. Look at him straight on and he’ll read it like a red flag. Standing straight, with your shoulders squared, rather than slumped, can mean the difference between whether your dog obeys a command or ignores it. Breathing even and deeply—rather than holding your breath—can mean the difference between defusing a tense situation and igniting it. “I think they are looking at our eyes and where our eyes are looking, and what our eyes look like,” the ethologist Patricia McConnell, who teaches at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, says. “A rounded eye with a dilated pupil is a sign of high arousal and aggression in a dog. I believe they pay a tremendous amount of attention to how relaxed our face is and how relaxed our facial muscles are, because that’s a big cue for them with each other. Is the jaw relaxed? Is the mouth slightly open? And then the arms. They pay a tremendous amount of attention to where our arms go.”

In the book The Other End of the Leash, McConnell decodes one of the most common of all human-dog interactions—the meeting between two leashed animals on a walk. To us, it’s about one dog sizing up another. To her, it’s about two dogs sizing up each other after first sizing up their respective owners. The owners “are often anxious about how well the dogs will get along,” she writes, “and if you watch them instead of the dogs, you’ll often notice that the humans will hold their breath and round their eyes and mouths in an ‘on alert’ expression. Since these behaviors are expressions of offensive aggression in canine culture, I suspect that the humans are unwittingly signalling tension. If you exaggerate this by tightening the leash, as many owners do, you can actually cause the dogs to attack each other. Think of it: the dogs are in a tense social encounter, surrounded by support from their own pack, with the humans forming a tense, staring, breathless circle around them. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen dogs shift their eyes toward their owners’ frozen faces, and then launch growling at the other dog.”

When Cesar walked down the stairs of Patrice and Scott’s home then, and crouched down in the back yard, JonBee looked at him, intently. And what he saw was someone who moved in a very particular way. Cesar is fluid. “He’s beautifully organized intra-physically,” Karen Bradley, who heads the graduate dance program at the University of Maryland, said when she first saw tapes of Cesar in action. “That lower-unit organization—I wonder whether he was a soccer player.” Movement experts like Bradley use something called Laban Movement Analysis to make sense of movement, describing, for instance, how people shift their weight, or how fluid and symmetrical they are when they move, or what kind of “effort” it involves. Is it direct or indirect—that is, what kind of attention does the movement convey? Is it quick or slow? Is it strong or light—that is, what is its intention? Is it bound or free—that is, how much precision is involved? If you want to emphasize a point, you might bring your hand down across your body in a single, smooth motion. But how you make that motion greatly affects how your point will be interpreted by your audience. Ideally, your hand would come down in an explosive, bound movement—that is, with accelerating force, ending abruptly and precisely—and your head and shoulders would descend simultaneously, so posture and gesture would be in harmony. Suppose, though, that your head and shoulders moved upward as your hand came down, or your hand came down in a free, implosive manner—that is, with a kind of a vague, decelerating force. Now your movement suggests that you are making a point on which we all agree, which is the opposite of your intention. Combinations of posture and gesture are called phrasing, and the great communicators are those who match their phrasing with their communicative intentions—who understand, for instance, that emphasis requires them to be bound and explosive. To Bradley, Cesar had beautiful phrasing.

There he is talking to Patrice and Scott. He has his hands in front of him, in what Laban analysts call the sagittal plane—that is, the area directly in front of and behind the torso. He then leans forward for emphasis. But as he does he lowers his hands to waist level, and draws them toward his body, to counterbalance the intrusion of his posture. And, when he leans backward again, the hands rise up, to fill the empty space. It’s not the kind of thing you’d ever notice. But, when it’s pointed out, its emotional meaning is unmistakable. It is respectful and reassuring. It communicates without being intrusive. Bradley was watching Cesar with the sound off, and there was one sequence she returned to again and again, in which Cesar was talking to a family, and his right hand swung down in a graceful arc across his chest. “He’s dancing,” Bradley said. “Look at that. It’s gorgeous. It’s such a gorgeous little dance.

“The thing is, his phrases are of mixed length,” she went on. “Some of them are long. Some of them are very short. Some of them are explosive phrases, loaded up in the beginning and then trailing off. Some of them are impactive—building up, and then coming to a sense of impact at the end. What they are is appropriate to the task. That’s what I mean by ‘versatile.’ ”

Movement analysts tend to like watching, say, Bill Clinton or Ronald Reagan; they had great phrasing. George W. Bush does not. During this year’s State of the Union address, Bush spent the entire speech swaying metronomically, straight down through his lower torso, a movement underscored, unfortunately, by the presence of a large vertical banner behind him. “Each shift ended with this focus that channels toward a particular place in the audience,” Bradley said. She mimed, perfectly, the Bush gaze—the squinty, fixated look he reserves for moments of great solemnity—and gently swayed back and forth. “It’s a little primitive, a little regressed.” The combination of the look, the sway, and the gaze was, to her mind, distinctly adolescent. When people say of Bush that he seems eternally boyish, this is in part what they’re referring to. He moves like a boy, which is fine, except that, unlike such movement masters as Reagan and Clinton, he can’t stop moving like a boy when the occasion demands a more grown-up response.

“Mostly what we see in the normal population is undifferentiated phrasing,” Bradley said. “And then you have people who are clearly preferential in their phrases, like my husband. He’s Mr. Horizontal. When he’s talking in a meeting, he’s back. He’s open. He just goes into this, this same long thing”—she leaned back, and spread her arms out wide and slowed her speech—“and it doesn’t change very much. He works with people who understand him, fortunately.” She laughed. “When we meet someone like this”—she nodded at Cesar, on the television screen—“what do we do? We give them their own TV series. Seriously. We reward them. We are drawn to them, because we can trust that we can get the message. It’s not going to be hidden. It contributes to a feeling of authenticity.”

Back to JonBee, from the beginning—only this time with the sound off. Cesar walks down the stairs. It’s not the same Cesar who whistled and brought forty-seven dogs to attention. This occasion calls for subtlety. “Did you see the way he walks? He drops his hands. They’re close to his side.” The analyst this time was Suzi Tortora, the author of The Dancing Dialogue. Tortora is a New York dance-movement psychotherapist, a tall, lithe woman with long dark hair and beautiful phrasing. She was in her office on lower Broadway, a large, empty, panelled room. “He’s very vertical,” Tortora said. “His legs are right under his torso. He’s not taking up any space. And he slows down his gait. He’s telling the dog, ‘I’m here by myself. I’m not going to rush. I haven’t introduced myself yet. Here I am. You can feel me.’ ” Cesar crouches down next to JonBee. His body is perfectly symmetrical, the center of gravity low. He looks stable, as though you couldn’t knock him over, which conveys a sense of calm.

JonBee was investigating Cesar, squirming nervously. When JonBee got too jumpy, Cesar would correct him, with a tug on the leash. Because Cesar was talking and the correction was so subtle, it was easy to miss. Stop. Rewind. Play. “Do you see how rhythmic it is?” Tortora said. “He pulls. He waits. He pulls. He waits. He pulls. He waits. The phrasing is so lovely. It’s predictable. To a dog that is all over the place, he’s bringing a rhythm. But it isn’t a panicked rhythm. It has a moderate tempo to it. There was room to wander. And it’s not attack, attack. It wasn’t long and sustained. It was quick and light. I would bet that with dogs like this, where people are so afraid of them being aggressive and so defensive around them, that there is a lot of aggressive strength directed at them. There is no aggression here. He’s using strength without it being aggressive.”

Cesar moves into the living room. The fight begins. “Look how he involves the dog,” Tortora said. “He’s letting the dog lead. He’s giving the dog room.” This was not a Secret Service agent wrestling an assailant to the ground. Cesar had his body vertical, and his hand high above JonBee holding the leash, and, as JonBee turned and snapped and squirmed and spun and jumped and lunged and struggled, Cesar seemed to be moving along with him, providing a loose structure for his aggression. It may have looked like a fight, but Cesar wasn’t fighting. And what was JonBee doing? Child psychologists talk about the idea of regulation. If you expose healthy babies, repeatedly, to a very loud noise, eventually they will be able to fall asleep. They’ll become habituated to the noise: the first time the noise is disruptive, but, by the second or third time, they’ve learned to handle the disruption, and block it out. They’ve regulated themselves. Children throwing tantrums are said to be in a state of dysregulation. They’ve been knocked off-kilter in some way, and cannot bring themselves back to baseline. JonBee was dysregulated. He wasn’t fighting; he was throwing a tantrum. And Cesar was the understanding parent. When JonBee paused, to catch his breath, Cesar paused with him. When JonBee bit Cesar, Cesar brought his finger to his mouth, instinctively, but in a smooth and fluid and calm motion that betrayed no anxiety. “Timing is a big part of Cesar’s repertoire,” Tortora went on. “His movements right now aren’t complex. There aren’t a lot of efforts together at one time. His range of movement qualities is limited. Look at how he’s narrowing. Now he’s enclosing.” As JonBee calmed down, Cesar began caressing him. His touch was firm but not aggressive; not so strong as to be abusive and not so light as to be insubstantial and irritating. Using the language of movement—the plainest and most transparent of all languages—Cesar was telling JonBee that he was safe. Now JonBee was lying on his side, mouth relaxed, tongue out. “Look at that, look at the dog’s face,” Tortora said. This was not defeat; this was relief.

Later, when Cesar tried to show Scott how to placate JonBee, Scott couldn’t do it, and Cesar made him stop. “You’re still nervous,” Cesar told him. “You are still unsure. That’s how you become a target.” It isn’t as easy as it sounds to calm a dog. “There, there,” in a soothing voice, accompanied by a nice belly scratch, wasn’t enough for JonBee, because he was reading gesture and posture and symmetry and the precise meaning of touch. He was looking for clarity and consistency. Scott didn’t have it. “Look at the tension and aggression in his face,” Tortora said, when the camera turned to Scott. It was true. Scott had a long and craggy face, with high, wide cheekbones and pronounced lips, and his movements were taut and twitchy. “There’s a bombardment of actions, quickness combined with tension, a quality in how he is using his eyes and focus—a darting,” Tortora said. “He gesticulates in a way that is complex. There is a lot going on. So many different qualities of movement happening at the same time. It leads those who watch him to get distracted.” Scott is a character actor, with a list of credits going back thirty years. The tension and aggression in his manner made him interesting and complicated—which works for Hollywood but doesn’t work for a troubled dog. Scott said he loved JonBee, but the quality of his movement did not match his emotions.

“They’re all sons of bitches.”

For a number of years, Tortora has worked with Eric (not his real name), an autistic boy with severe language and communication problems. Tortora video-taped some of their sessions, and in one, four months after they started to work together, Eric is standing in the middle of Tortora’s studio in Cold Spring, New York, a beautiful dark-haired three-and-a-half-year-old, wearing only a diaper. His mother is sitting to the side, against the wall. In the background, you can hear the soundtrack to Riverdance, which happens to be Eric’s favorite album. Eric is having a tantrum.

He gets up and runs toward the stereo. Then he runs back and throws himself down on his stomach, arms and legs flailing. Tortora throws herself down on the ground, just as he did. He sits up. She sits up. He twists. She twists. He squirms. She squirms. “When Eric is running around, I didn’t say, ‘Let’s put on quiet music.’ I can’t turn him off, because he can’t turn off,” Tortora said. “He can’t go from zero to sixty and then back down to zero. With a typical child, you might say, ‘Take a deep breath. Reason with me’—and that might work. But not with children like this. They are in their world by themselves. I have to go in there and meet them and bring them back out.”

Tortora sits up on her knees, and faces Eric. His legs are moving in every direction, and she takes his feet into her hands. Slowly, and subtly, she begins to move his legs in time with the music. Eric gets up and runs to the corner of the room and back again. Tortora gets up and mirrors his action, but this time she moves more fluidly and gracefully than he did. She takes his feet again. This time, she moves Eric’s entire torso, opening the pelvis in a contra-lateral twist. “I’m standing above him, looking directly at him. I am very symmetrical. So I’m saying to him, I’m stable. I’m here. I’m calm. I’m holding him at the knees and giving him sensory input. It’s firm and clear. Touch is an incredible tool. It’s another way to speak.”

She starts to rock his knees from side to side. Eric begins to calm down. He begins to make slight adjustments to the music. His legs move more freely, more lyrically. His movement is starting to get organized. He goes back into his mother’s arms. He’s still upset, but his cry has softened. Tortora sits and faces him—stable, symmetrical, direct eye contact.

His mother says, “You need a tissue?”

Eric nods.

Tortora brings him a tissue. Eric’s mother says that she needs a tissue. Eric gives his tissue to his mother.

“Can we dance?” Tortora asks him.

“O.K.,” he says, in a small voice.

It was impossible to see Tortora with Eric and not think of Cesar with JonBee: here was the same extraordinary energy and intelligence and personal force marshalled on behalf of the helpless, the same calm in the face of chaos, and, perhaps most surprising, the same gentleness. When we talk about people with presence, we often assume that they have a strong personality—that they sweep us all up in their own personal whirlwind. Our model is the Pied Piper, who played his irresistible tune and every child in Hamelin blindly followed. But Cesar Millan and Suzi Tortora play different tunes, in different situations. And they don’t turn their back, and expect others to follow. Cesar let JonBee lead; Tortora’s approaches to Eric were dictated by Eric. Presence is not just versatile; it’s also reactive. Certain people, we say, “command our attention,” but the verb is all wrong. There is no commanding, only soliciting. The dogs in the dog run wanted someone to tell them when to start and stop; they were refugees from anarchy and disorder. Eric wanted to enjoy Riverdance. It was his favorite music. Tortora did not say, “Let us dance.” She asked, “Can we dance?”

Then Tortora gets a drum, and starts to play. Eric’s mother stands up and starts to circle the room, in an Irish step dance. Eric is lying on the ground, and slowly his feet start to tap in time with the music. He gets up. He walks to the corner of the room, disappears behind a partition, and then reenters, triumphant. He begins to dance, playing an imaginary flute as he circles the room.

When Cesar was twenty-one, he travelled from his home town to Tijuana, and a “coyote” took him across the border, for a hundred dollars. They waited in a hole, up to their chests in water, and then ran over the mudflats, through a junk yard, and across a freeway. A taxi took him to San Diego. After a month on the streets, grimy and dirty, he walked into a dog-grooming salon and got a job, working with the difficult cases and sleeping in the offices at night. He moved to Los Angeles, and took a day job detailing limousines while he ran his dog-psychology business out of a white Chevy Astrovan. When he was twenty-three, he fell in love with an American girl named Illusion. She was seventeen, small, dark, and very beautiful. A year later, they got married.

“Cesar was a macho-istic, egocentric person who thought the world revolved around him,” Illusion recalled, of their first few years together. “His view was that marriage was where a man tells a woman what to do. Never give affection. Never give compassion or understanding. Marriage is about keeping the man happy, and that’s where it ends.” Early in their marriage, Illusion got sick, and was in the hospital for three weeks. “Cesar visited once, for less than two hours,” she said. “I thought to myself, This relationship is not working out. He just wanted to be with his dogs.” They had a new baby, and no money. They separated. Illusion told Cesar that she would divorce him if he didn’t get into therapy. He agreed, reluctantly. “The therapist’s name was Wilma,” Illusion went on. “She was a strong African-American woman. She said, ‘You want your wife to take care of you, to clean the house. Well, she wants something, too. She wants your affection and love.’ ” Illusion remembers Cesar scribbling furiously on a pad. “He wrote that down. He said, ‘That’s it! It’s like the dogs. They need exercise, discipline, and affection.’ ” Illusion laughed. “I looked at him, upset, because why the hell are you talking about your dogs when you should be talking about us?”

“I was fighting it,” Cesar said. “Two women against me, blah, blah, blah. I had to get rid of the fight in my mind. That was very difficult. But that’s when the light bulb came on. Women have their own psychology.”

Cesar could calm a stray off the street, yet, at least in the beginning, he did not grasp the simplest of truths about his own wife. “Cesar related to dogs because he didn’t feel connected to people,” Illusion said. “His dogs were his way of feeling like he belonged in the world, because he wasn’t people friendly. And it was hard for him to get out of that.” In Mexico, on his grandfather’s farm, dogs were dogs and humans were humans: each knew its place. But in America dogs were treated like children, and owners had shaken up the hierarchy of human and animal. Sugar’s problem was Lynda. JonBee’s problem was Scott. Cesar calls that epiphany in the therapist’s office the most important moment in his life, because it was the moment when he understood that to succeed in the world he could not just be a dog whisperer. He needed to be a people whisperer.

For his show, Cesar once took a case involving a Chihuahua named Bandit. Bandit had a large, rapper-style diamond-encrusted necklace around his neck spelling “Stud.” His owner was Lori, a voluptuous woman with an oval face and large, pleading eyes. Bandit was out of control, terrorizing guests and menacing other dogs. Three trainers had failed to get him under control.

Lori was on the couch in her living room as she spoke to Cesar. Bandit was sitting in her lap. Her teen-age son, Tyler, was sitting next to her.

“About two weeks after his first visit with the vet, he started to lose a lot of hair,” Lori said. “They said that he had Demodex mange.” Bandit had been sold to her as a show-quality dog, she recounted, but she had the bloodline checked, and learned that he had come from a puppy mill. “He didn’t have any human contact,” she went on. “So for three months he was getting dipped every week to try to get rid of the symptoms.” As she spoke, her hands gently encased Bandit. “He would hide inside my shirt and lay his head right by my heart, and stay there.” Her eyes were moist. “He was right here on my chest.”

“So your husband cooperated?” Cesar asked. He was focussed on Lori, not on Bandit. This is what the new Cesar understood that the old Cesar did not.

“He was our baby. He was in need of being nurtured and helped and he was so scared all the time.”

“Do you still feel the need of feeling sorry about him?”

“Yeah. He’s so cute.”

Cesar seemed puzzled. He didn’t know why Lori would still feel sorry for her dog.

Lori tried to explain. “He’s so small and he’s helpless.”

“But do you believe that he feels helpless?”

Lori still had her hands over the dog, stroking him. Tyler was looking at Cesar, and then at his mother, and then down at Bandit. Bandit tensed. Tyler reached over to touch the dog, and Bandit leaped out of Lori’s arms and attacked him, barking and snapping and growling. Tyler, startled, jumped back. Lori, alarmed, reached out, and—this was the critical thing—put her hands around Bandit in a worried, caressing motion, and lifted him back into her lap. It happened in an instant.

Cesar stood up. “Give me the space,” he said, gesturing for Tyler to move aside. “Enough dogs attacking humans, and humans not really blocking him, so he is only becoming more narcissistic. It is all about him. He owns you.” Cesar was about as angry as he ever gets. “It seems like you are favoring the dog, and hopefully that is not the truth.… If Tyler kicked the dog, you would correct him. The dog is biting your son, and you are not correcting hard enough.” Cesar was in emphatic mode now, his phrasing sure and unambiguous. “I don’t understand why you are not putting two and two together.”

Bandit was nervous. He started to back up on the couch. He started to bark. Cesar gave him a look out of the corner of his eye. Bandit shrank. Cesar kept talking. Bandit came at Cesar. Cesar stood up. “I have to touch,” he said, and he gave Bandit a sharp nudge with his elbow. Lori looked horrified.

Cesar laughed, incredulously. “You are saying that it is fair for him to touch us but not fair for us to touch him?” he asked.

Lori leaned forward to object.

“You don’t like that, do you?” Cesar said, in his frustration speaking to the whole room now. “It’s not going to work. This is a case that is not going to work, because the owner doesn’t want to allow what you normally do with your kids.… The hardest part for me is that the father or mother chooses the dog instead of the son. That’s hard for me. I love dogs. I’m the dog whisperer. You follow what I’m saying? But I would never choose a dog over my son.”

He stopped. He had had enough of talking. There was too much talking, anyhow. People saying, “I love you,” with a touch that didn’t mean “I love you.” People saying, “There, there,” with gestures that did not soothe. People saying, “I’m your mother,” while reaching out to a Chihuahua instead of their own flesh and blood. Tyler looked stricken. Lori shifted nervously in her seat. Bandit growled. Cesar turned to the dog and said “Sh-h-h.” And everyone was still.

| 2006 |