One afternoon last February, Guy Clairoux picked up his two-and-a-half-year-old son, Jayden, from day care and walked him back to their house in the west end of Ottawa, Ontario. They were almost home. Jayden was straggling behind, and, as his father’s back was turned, a pit bull jumped over a back-yard fence and lunged at Jayden. “The dog had his head in its mouth and started to do this shake,” Clairoux’s wife, JoAnn Hartley, said later. As she watched in horror, two more pit bulls jumped over the fence, joining in the assault. She and Clairoux came running, and he punched the first of the dogs in the head, until it dropped Jayden, and then he threw the boy toward his mother. Hartley fell on her son, protecting him with her body. “JoAnn!” Clairoux cried out, as all three dogs descended on his wife. “Cover your neck, cover your neck.” A neighbor, sitting by her window, screamed for help. Her partner and a friend, Mario Gauthier, ran outside. A neighborhood boy grabbed his hockey stick and threw it to Gauthier. He began hitting one of the dogs over the head, until the stick broke. “They wouldn’t stop,” Gauthier said. “As soon as you’d stop, they’d attack again. I’ve never seen a dog go so crazy. They were like Tasmanian devils.” The police came. The dogs were pulled away, and the Clairouxes and one of the rescuers were taken to the hospital. Five days later, the Ontario legislature banned the ownership of pit bulls. “Just as we wouldn’t let a great white shark in a swimming pool,” the province’s attorney general, Michael Bryant, had said, “maybe we shouldn’t have these animals on the civilized streets.”

Pit bulls, descendants of the bulldogs used in the nineteenth century for bull baiting and dogfighting, have been bred for “gameness,” and thus a lowered inhibition to aggression. Most dogs fight as a last resort, when staring and growling fail. A pit bull is willing to fight with little or no provocation. Pit bulls seem to have a high tolerance for pain, making it possible for them to fight to the point of exhaustion. Whereas guard dogs like German shepherds usually attempt to restrain those they perceive to be threats by biting and holding, pit bulls try to inflict the maximum amount of damage on an opponent. They bite, hold, shake, and tear. They don’t growl or assume an aggressive facial expression as warning. They just attack. “They are often insensitive to behaviors that usually stop aggression,” one scientific review of the breed states. “For example, dogs not bred for fighting usually display defeat in combat by rolling over and exposing a light underside. On several occasions, pit bulls have been reported to disembowel dogs offering this signal of submission.” In epidemiological studies of dog bites, the pit bull is overrepresented among dogs known to have seriously injured or killed human beings, and, as a result, pit bulls have been banned or restricted in several Western European countries, China, and numerous cities and municipalities across North America. Pit bulls are dangerous.

Of course, not all pit bulls are dangerous. Most don’t bite anyone. Meanwhile, Dobermans and Great Danes and German shepherds and Rottweilers are frequent biters as well, and the dog that recently mauled a Frenchwoman so badly that she was given the world’s first face transplant was, of all things, a Labrador retriever. When we say that pit bulls are dangerous, we are making a generalization, just as insurance companies use generalizations when they charge young men more for car insurance than the rest of us (even though many young men are perfectly good drivers), and doctors use generalizations when they tell overweight middle-aged men to get their cholesterol checked (even though many overweight middle-aged men won’t experience heart trouble). Because we don’t know which dog will bite someone or who will have a heart attack or which drivers will get in an accident, we can make predictions only by generalizing. As the legal scholar Frederick Schauer has observed, “painting with a broad brush” is “an often inevitable and frequently desirable dimension of our decision-making lives.”

Another word for generalization, though, is “stereotype,” and stereotypes are usually not considered desirable dimensions of our decision-making lives. The process of moving from the specific to the general is both necessary and perilous. A doctor could, with some statistical support, generalize about men of a certain age and weight. But what if generalizing from other traits—such as high blood pressure, family history, and smoking—saved more lives? Behind each generalization is a choice of what factors to leave in and what factors to leave out, and those choices can prove surprisingly complicated. After the attack on Jayden Clairoux, the Ontario government chose to make a generalization about pit bulls. But it could also have chosen to generalize about powerful dogs, or about the kinds of people who own powerful dogs, or about small children, or about back-yard fences—or, indeed, about any number of other things to do with dogs and people and places. How do we know when we’ve made the right generalization?

In July of last year, following the transit bombings in London, the New York City Police Department announced that it would send officers into the subways to conduct random searches of passengers’ bags. On the face of it, doing random searches in the hunt for terrorists—as opposed to being guided by generalizations—seems like a silly idea. As a columnist in New York wrote at the time, “Not just ‘most’ but nearly every jihadi who has attacked a Western European or American target is a young Arab or Pakistani man. In other words, you can predict with a fair degree of certainty what an Al Qaeda terrorist looks like. Just as we have always known what Mafiosi look like—even as we understand that only an infinitesimal fraction of Italian-Americans are members of the mob.”

But wait: do we really know what mafiosi look like? In The Godfather, where most of us get our knowledge of the Mafia, the male members of the Corleone family were played by Marlon Brando, who was of Irish and French ancestry, James Caan, who is Jewish, and two Italian-Americans, Al Pacino and John Cazale. To go by The Godfather, mafiosi look like white men of European descent, which, as generalizations go, isn’t terribly helpful. Figuring out what an Islamic terrorist looks like isn’t any easier. Muslims are not like the Amish: they don’t come dressed in identifiable costumes. And they don’t look like basketball players; they don’t come in predictable shapes and sizes. Islam is a religion that spans the globe.

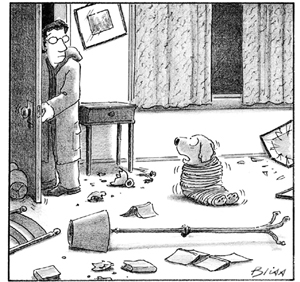

“Artie, they took my bowl.”

“We have a policy against racial profiling,” Raymond Kelly, New York City’s police commissioner, told me. “I put it in here in March of the first year I was here. It’s the wrong thing to do, and it’s also ineffective. If you look at the London bombings, you have three British citizens of Pakistani descent. You have Germaine Lindsay, who is Jamaican. You have the next crew, on July 21st, who are East African. You have a Chechen woman in Moscow in early 2004 who blows herself up in the subway station. So whom do you profile? Look at New York City. Forty percent of New Yorkers are born outside the country. Look at the diversity here. Who am I supposed to profile?”

Kelly was pointing out what might be called profiling’s “category problem.” Generalizations involve matching a category of people to a behavior or trait—overweight middle-aged men to heart-attack risk, young men to bad driving. But, for that process to work, you have to be able both to define and to identify the category you are generalizing about. “You think that terrorists aren’t aware of how easy it is to be characterized by ethnicity?” Kelly went on. “Look at the 9/11 hijackers. They came here. They shaved. They went to topless bars. They wanted to blend in. They wanted to look like they were part of the American dream. These are not dumb people. Could a terrorist dress up as a Hasidic Jew and walk into the subway, and not be profiled? Yes. I think profiling is just nuts.”

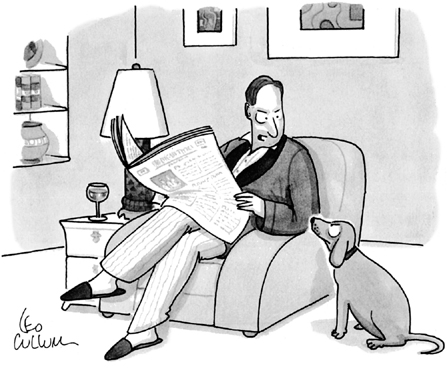

“Yes, you’re my best friend, and no, I’m not lending you forty thousand dollars.”

Pit-bull bans involve a category problem, too, because pit bulls, as it happens, aren’t a single breed. The name refers to dogs belonging to a number of related breeds, such as the American Staffordshire terrier, the Staffordshire bull terrier, and the American pit bull terrier—all of which share a square and muscular body, a short snout, and a sleek, short-haired coat. Thus the Ontario ban prohibits not only these three breeds but any “dog that has an appearance and physical characteristics that are substantially similar” to theirs; the term of art is “pit bull–type” dogs. But what does that mean? Is a cross between an American pit bull terrier and a golden retriever a pit bull–type dog or a golden retriever–type dog? If thinking about muscular terriers as pit bulls is a generalization, then thinking about dangerous dogs as anything substantially similar to a pit bull is a generalization about a generalization. “The way a lot of these laws are written, pit bulls are whatever they say they are,” Lora Brashears, a kennel manager in Pennsylvania, says. “And for most people it just means big, nasty, scary dog that bites.”

The goal of pit-bull bans, obviously, isn’t to prohibit dogs that look like pit bulls. The pit-bull appearance is a proxy for the pit-bull temperament—for some trait that these dogs share. But “pit bullness” turns out to be elusive as well. The supposedly troublesome characteristics of the pit-bull type—its gameness, its determination, its insensitivity to pain—are chiefly directed toward other dogs. Pit bulls were not bred to fight humans. On the contrary: a dog that went after spectators, or its handler, or the trainer, or any of the other people involved in making a dogfighting dog a good dogfighter was usually put down. (The rule in the pit-bull world was “Man-eaters die.”)

A Georgia-based group called the American Temperament Test Society has put twenty-five thousand dogs through a ten-part standardized drill designed to assess a dog’s stability, shyness, aggressiveness, and friendliness in the company of people. A handler takes a dog on a six-foot lead and judges its reaction to stimuli such as gunshots, an umbrella opening, and a weirdly dressed stranger approaching in a threatening way. Eighty-four percent of the pit bulls that have been given the test have passed, which ranks pit bulls ahead of beagles, Airedales, bearded collies, and all but one variety of dachshund. “We have tested somewhere around a thousand pit bull–type dogs,” Carl Herkstroeter, the president of the A.T.T.S., says. “I’ve tested half of them. And of the number I’ve tested I have disqualified one pit bull because of aggressive tendencies. They have done extremely well. They have a good temperament. They are very good with children.” It can even be argued that the same traits that make the pit bull so aggressive toward other dogs are what make it so nice to humans. “There are a lot of pit bulls these days who are licensed therapy dogs,” the writer Vicki Hearne points out. “Their stability and resoluteness make them excellent for work with people who might not like a more bouncy, flibbertigibbet sort of dog. When pit bulls set out to provide comfort, they are as resolute as they are when they fight, but what they are resolute about is being gentle. And, because they are fearless, they can be gentle with anybody.”

Then which are the pit bulls that get into trouble? “The ones that the legislation is geared toward have aggressive tendencies that are either bred in by the breeder, trained in by the trainer, or reinforced in by the owner,” Herkstroeter says. A mean pit bull is a dog that has been turned mean, by selective breeding, by being cross-bred with a bigger, human-aggressive breed like German shepherds or Rottweilers, or by being conditioned in such a way that it begins to express hostility to human beings. A pit bull is dangerous to people, then, not to the extent that it expresses its essential pit bullness but to the extent that it deviates from it. A pit-bull ban is a generalization about a generalization about a trait that is not, in fact, general. That’s a category problem.

One of the puzzling things about New York City is that, after the enormous and well-publicized reductions in crime in the mid-1990s, the crime rate has continued to fall. In the past two years, for instance, murder in New York has declined by almost 10 percent, rape by 12 percent, and burglary by more than 18 percent. Just in the last year, auto theft went down 11.8 percent. On a list of two hundred and forty cities in the United States with a population of a hundred thousand or more, New York City now ranks two hundred-and-twenty-second in crime, down near the bottom with Fontana, California, and Port St. Lucie, Florida. In the 1990s, the crime decrease was attributed to big obvious changes in city life and government—the decline of the drug trade, the gentrification of Brooklyn, the successful implementation of “broken windows” policing. But all those big changes happened a decade ago. Why is crime still falling?

The explanation may have to do with a shift in police tactics. The N.Y.P.D. has a computerized map showing, in real time, precisely where serious crimes are being reported, and at any moment the map typically shows a few dozen constantly shifting high-crime hot spots, some as small as two or three blocks square. What the N.Y.P.D. has done, under Commissioner Kelly, is to use the map to establish “impact zones,” and to direct newly graduated officers—who used to be distributed proportionally to precincts across the city—to these zones, in some cases doubling the number of officers in the immediate neighborhood. “We took two-thirds of our graduating class and linked them with experienced officers, and focussed on those areas,” Kelly said. “Well, what has happened is that over time we have averaged about a thirty-five percent crime reduction in impact zones.”

For years, experts have maintained that the incidence of violent crime is “inelastic” relative to police presence—that people commit serious crimes because of poverty and psychopathology and cultural dysfunction, along with spontaneous motives and opportunities. The presence of a few extra officers down the block, it was thought, wouldn’t make much difference. But the N.Y.P.D. experience suggests otherwise. More police means that some crimes are prevented, others are more easily solved, and still others are displaced—pushed out of the troubled neighborhood—which Kelly says is a good thing, because it disrupts the patterns and practices and social networks that serve as the basis for law-breaking. In other words, the relation between New York City (a category) and criminality (a trait) is unstable, and this kind of instability is another way in which our generalizations can be derailed.

Why, for instance, is it a useful rule of thumb that Kenyans are good distance runners? It’s not just that it’s statistically supportable today. It’s that it has been true for almost half a century, and that in Kenya the tradition of distance running is sufficiently rooted that something cataclysmic would have to happen to dislodge it. By contrast, the generalization that New York City is a crime-ridden place was once true and now, manifestly, isn’t. People who moved to sunny retirement communities like Port St. Lucie because they thought they were much safer than New York are suddenly in the position of having made the wrong bet.

The instability issue is a problem for profiling in law enforcement as well. The law professor David Cole once tallied up some of the traits that Drug Enforcement Administration agents have used over the years in making generalizations about suspected smugglers. Here is a sample:

Arrived late at night; arrived early in the morning; arrived in afternoon; one of the first to deplane; one of the last to deplane; deplaned in the middle; purchased ticket at the airport; made reservation on short notice; bought coach ticket; bought first-class ticket; used one-way ticket; used round-trip ticket; paid for ticket with cash; paid for ticket with small denomination currency; paid for ticket with large denomination currency; made local telephone calls after deplaning; made long distance telephone call after deplaning; pretended to make telephone call; traveled from New York to Los Angeles; traveled to Houston; carried no luggage; carried brand-new luggage; carried a small bag; carried a medium-sized bag; carried two bulky garment bags; carried two heavy suitcases; carried four pieces of luggage; overly protective of luggage; disassociated self from luggage; traveled alone; traveled with a companion; acted too nervous; acted too calm; made eye contact with officer; avoided making eye contact with officer; wore expensive clothing and jewelry; dressed casually; went to restroom after deplaning; walked rapidly through airport; walked slowly through airport; walked aimlessly through airport; left airport by taxi; left airport by limousine; left airport by private car; left airport by hotel courtesy van.

Some of these reasons for suspicion are plainly absurd, suggesting that there’s no particular rationale to the generalizations used by D.E.A. agents in stopping suspected drug smugglers. A way of making sense of the list, though, is to think of it as a catalogue of unstable traits. Smugglers may once have tended to buy one-way tickets in cash and carry two bulky suitcases. But they don’t have to. They can easily switch to round-trip tickets bought with a credit card, or a single carry-on bag, without losing their capacity to smuggle. There’s a second kind of instability here as well. Maybe the reason some of them switched from one-way tickets and two bulky suitcases was that law enforcement got wise to those habits, so the smugglers did the equivalent of what the jihadis seemed to have done in London, when they switched to East Africans because the scrutiny of young Arab and Pakistani men grew too intense. It doesn’t work to generalize about a relationship between a category and a trait when that relationship isn’t stable—or when the act of generalizing may itself change the basis of the generalization.

Before Kelly became the New York police commissioner, he served as the head of the U.S. Customs Service, and while he was there he overhauled the criteria that border-control officers use to identify and search suspected smugglers. There had been a list of forty-three suspicious traits. He replaced it with a list of six broad criteria. Is there something suspicious about their physical appearance? Are they nervous? Is there specific intelligence targeting this person? Does the drug-sniffing dog raise an alarm? Is there something amiss in their paperwork or explanations? Has contraband been found that implicates this person?

You’ll find nothing here about race or gender or ethnicity, and nothing here about expensive jewelry or deplaning at the middle or the end, or walking briskly or walking aimlessly. Kelly removed all the unstable generalizations, forcing customs officers to make generalizations about things that don’t change from one day or one month to the next. Some percentage of smugglers will always be nervous, will always get their story wrong, and will always be caught by the dogs. That’s why those kinds of inferences are more reliable than the ones based on whether smugglers are white or black, or carry one bag or two. After Kelly’s reforms, the number of searches conducted by the Customs Service dropped by about 75 percent, but the number of successful seizures improved by 25 percent. The officers went from making fairly lousy decisions about smugglers to making pretty good ones. “We made them more efficient and more effective at what they were doing,” Kelly said.

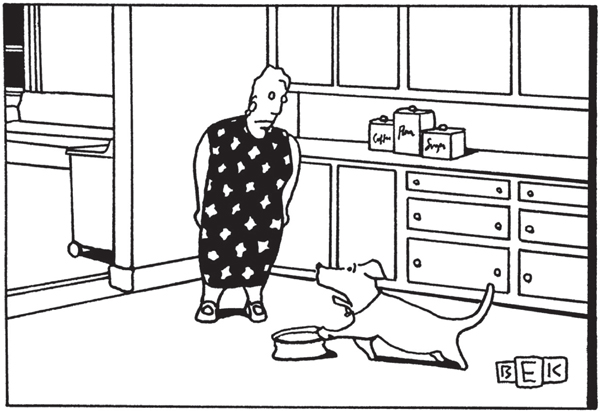

“The dog ate my magnetic insoles.”

Does the notion of a pit-bull menace rest on a stable or an unstable generalization? The best data we have on breed dangerousness are fatal dog bites, which serve as a useful indicator of just how much havoc certain kinds of dogs are causing. Between the late 1970s and the late 1990s, more than twenty-five breeds were involved in fatal attacks in the United States. Pit-bull breeds led the pack, but the variability from year to year is considerable. For instance, in the period from 1981 to 1982 fatalities were caused by five pit bulls, three mixed breeds, two St. Bernards, two German-shepherd mixes, a pure-bred German shepherd, a husky type, a Doberman, a Chow Chow, a Great Dane, a wolf-dog hybrid, a husky mix, and a pit-bull mix—but no Rottweilers. In 1995 and 1996, the list included ten Rottweilers, four pit bulls, two German shepherds, two huskies, two Chow Chows, two wolf-dog hybrids, two shepherd mixes, a Rottweiler mix, a mixed breed, a Chow Chow mix, and a Great Dane. The kinds of dogs that kill people change over time, because the popularity of certain breeds changes over time. The one thing that doesn’t change is the total number of the people killed by dogs. When we have more problems with pit bulls, it’s not necessarily a sign that pit bulls are more dangerous than other dogs. It could just be a sign that pit bulls have become more numerous.

“I’ve seen virtually every breed involved in fatalities, including Pomeranians and everything else, except a beagle or a basset hound,” Randall Lockwood, a senior vice-president of the A.S.P.C.A. and one of the country’s leading dog-bite experts, told me. “And there’s always one or two deaths attributable to malamutes or huskies, although you never hear people clamoring for a ban on those breeds. When I first started looking at fatal dog attacks, they largely involved dogs like German shepherds and shepherd mixes and St. Bernards—which is probably why Stephen King chose to make Cujo a St. Bernard, not a pit bull. I haven’t seen a fatality involving a Doberman for decades, whereas in the 1970s they were quite common. If you wanted a mean dog, back then, you got a Doberman. I don’t think I even saw my first pit-bull case until the middle to late 1980s, and I didn’t start seeing Rottweilers until I’d already looked at a few hundred fatal dog attacks. Now those dogs make up the preponderance of fatalities. The point is that it changes over time. It’s a reflection of what the dog of choice is among people who want to own an aggressive dog.”

There is no shortage of more stable generalizations about dangerous dogs, though. A 1991 study in Denver, for example, compared a hundred and seventy-eight dogs with a history of biting people with a random sample of a hundred and seventy-eight dogs with no history of biting. The breeds were scattered: German shepherds, Akitas, and Chow Chows were among those most heavily represented. (There were no pit bulls among the biting dogs in the study, because Denver banned pit bulls in 1989.) But a number of other, more stable factors stand out. The biters were 6.2 times as likely to be male than female, and 2.6 times as likely to be intact than neutered. The Denver study also found that biters were 2.8 times as likely to be chained as unchained. “About twenty percent of the dogs involved in fatalities were chained at the time, and had a history of long-term chaining,” Lockwood said. “Now, are they chained because they are aggressive or aggressive because they are chained? It’s a bit of both. These are animals that have not had an opportunity to become socialized to people. They don’t necessarily even know that children are small human beings. They tend to see them as prey.”

In many cases, vicious dogs are hungry or in need of medical attention. Often, the dogs had a history of aggressive incidents, and, overwhelmingly, dog-bite victims were children (particularly small boys) who were physically vulnerable to attack and may also have unwittingly done things to provoke the dog, like teasing it, or bothering it while it was eating. The strongest connection of all, though, is between the trait of dog viciousness and certain kinds of dog owners. In about a quarter of fatal dog-bite cases, the dog owners were previously involved in illegal fighting. The dogs that bite people are, in many cases, socially isolated because their owners are socially isolated, and they are vicious because they have owners who want a vicious dog. The junk-yard German shepherd—which looks as if it would rip your throat out—and the German-shepherd guide dog are the same breed. But they are not the same dog, because they have owners with different intentions.

“A fatal dog attack is not just a dog bite by a big or aggressive dog,” Lockwood went on. “It is usually a perfect storm of bad human-canine interactions—the wrong dog, the wrong background, the wrong history in the hands of the wrong person in the wrong environmental situation. I’ve been involved in many legal cases involving fatal dog attacks, and, certainly, it’s my impression that these are generally cases where everyone is to blame. You’ve got the unsupervised three-year-old child wandering in the neighborhood killed by a starved, abused dog owned by the dogfighting boyfriend of some woman who doesn’t know where her child is. It’s not old Shep sleeping by the fire who suddenly goes bonkers. Usually there are all kinds of other warning signs.”

Jayden Clairoux was attacked by Jada, a pit-bull terrier, and her two pit-bull–bullmastiff puppies, Agua and Akasha. The dogs were owned by a twenty-one-year-old man named Shridev Café, who worked in construction and did odd jobs. Five weeks before the Clairoux attack, Café’s three dogs got loose and attacked a sixteen-year-old boy and his four-year-old half brother while they were ice skating. The boys beat back the animals with a snow shovel and escaped into a neighbor’s house. Café was fined, and he moved the dogs to his seventeen-year-old girlfriend’s house. This was not the first time that he ran into trouble last year; a few months later, he was charged with domestic assault, and, in another incident, involving a street brawl, with aggravated assault. “Shridev has personal issues,” Cheryl Smith, a canine-behavior specialist who consulted on the case, says. “He’s certainly not a very mature person.” Agua and Akasha were now about seven months old. The court order in the wake of the first attack required that they be muzzled when they were outside the home and kept in an enclosed yard. But Café did not muzzle them, because, he said later, he couldn’t afford muzzles, and apparently no one from the city ever came by to force him to comply. A few times, he talked about taking his dogs to obedience classes, but never did. The subject of neutering them also came up—particularly Agua, the male—but neutering cost a hundred dollars, which he evidently thought was too much money, and when the city temporarily confiscated his animals after the first attack it did not neuter them, either, because Ottawa does not have a policy of preemptively neutering dogs that bite people.

On the day of the second attack, according to some accounts, a visitor came by the house of Café’s girlfriend, and the dogs got wound up. They were put outside, where the snowbanks were high enough so that the back-yard fence could be readily jumped. Jayden Clairoux stopped and stared at the dogs, saying, “Puppies, puppies.” His mother called out to his father. His father came running, which is the kind of thing that will rile up an aggressive dog. The dogs jumped the fence, and Agua took Jayden’s head in his mouth and started to shake. It was a textbook dog-biting case: un-neutered, ill-trained, charged-up dogs, with a history of aggression and an irresponsible owner, somehow get loose, and set upon a small child. The dogs had already passed through the animal bureaucracy of Ottawa, and the city could easily have prevented the second attack with the right kind of generalization—a generalization based not on breed but on the known and meaningful connection between dangerous dogs and negligent owners. But that would have required someone to track down Shridev Café, and check to see whether he had bought muzzles, and someone to send the dogs to be neutered after the first attack, and an animal-control law that insured that those whose dogs attack small children forfeit their right to have a dog. It would have required, that is, a more exacting set of generalizations to be more exactingly applied. It’s always easier just to ban the breed.

| 2006 |

“This isn’t tap water, is it?”