Blanche Saunders, a dark-haired, wiry, youthful-looking woman of forty-five with a pronounced affinity for black standard poodles, is this country’s best-known practitioner of Obedience Training, an up-and-coming branch of pedagogy that she has been instrumental in popularizing in America during the past fifteen years. Among Miss Saunders’ professional acquaintances—dog fanciers whose affinities range all the way from Afghan hounds to Yorkshire terriers—the word “obedience” has but one meaning. It denotes the social polish that a qualified trainer can impart to a dog through the medium of his owner, or at least to any dog able and willing to react cooperatively to such exclamations as “Hup!” (or “Hop!”), “Pfui!” (or “Phooey!”), and “Heel!,” to sit or lie motionless for prolonged periods while interlopers do their best to distract him, to bound over a series of hurdles with a dumbbell gripped between his teeth, and otherwise either to control himself or channel his energies along more or less useful lines in everyday life. Since, unlike more traditional systems of education, Obedience Training involves a chain of command, rather than direct communication between teacher and pupil, Miss Saunders can’t exactly be classified as a dog trainer. Instead, she thinks of herself as a trainer of dog owners, those ineffectual bipeds whose only reason for existence is to act as intermediaries between her and their dogs. Some dog owners who have undergone the rigors of Obedience Training have been inclined to view the program as discriminatory, for the certificates and degrees Miss Saunders doles out upon the completion of her courses are awarded not to the owners but to their pets. Most owners, however, accept their anomalous status with good grace and when their dogs are guilty of a fault, or in extreme cases a flunk-out, sportingly insist that they and not their pets are to blame.

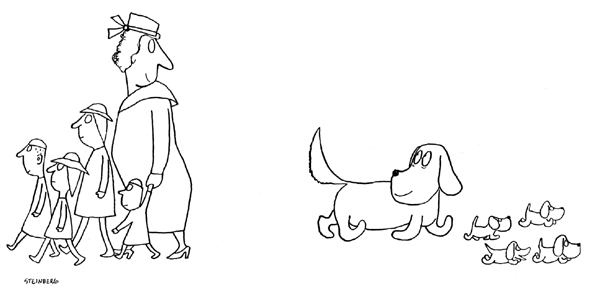

All this is as it should be, in the opinion of Obedience Training experts, but they often wish that dog owners, in their day-to-day dealings with their pets, would take a firmer stand. The Obedience Training people point out that dogs, as opposed to cats, are fundamentally amenable to being bossed around and that it is therefore not becoming for dog owners to take a subservient attitude toward the whims of their animals. According to this view, the dog owners of America, by allowing their dogs to precede them through doorways, to monopolize and muddy their furniture, to take sips from their cocktails or tidbits from their tables, and to intimidate, or even bite, their guests, not only have managed to lose the respect of their maladjusted animals but have become one of the major educational challenges of our day. There can be no denying that Miss Saunders has met this challenge with praiseworthy vigor, and from every conceivable angle. She has put in her most direct pedagogical licks in New York, where since 1944 she has been conducting Obedience Training courses, each consisting of nine lessons, in various armories and gymnasiums, mostly under the sponsorship of the A.S.P.C.A. The tuition for a course, for which Miss Saunders receives a fee of anywhere up to five hundred dollars, depending on the size of the class, is nine dollars. To date, about twenty-two hundred men, women, and adolescents have turned up for these courses, snaked along by their dogs and clinging to the wrong, or hind, end of the leash. “By the time they’ve finished the nine lessons,” an A.S.P.C.A. official said proudly the other day, “the relative positions on the leashes have been reversed in at least two-thirds of the cases.”

A considerably larger group of dog owners has had its eyes opened to the merits of Obedience work through a manual Miss Saunders has written, called Training You to Train Your Dog, published by Doubleday in 1946 and listed by the Times last December as a “hidden best seller,” meaning that it belongs, along with dictionaries and cookbooks, in that enviable category of books that, though they never reach the best-seller lists, continue to be bought in respectable quantities over a long period of time. So far, forty thousand copies of Miss Saunders’ book have been sold. In addition to fulfilling the obligation implicit in its title, this volume has an unexpected appeal for its purchasers, many of whom ordinarily have little time for reading anything farther afield than the American Kennel Gazette and Leash and Collar, in that it gives them a nodding acquaintance with the prose style of Walter Lippmann. Mr. Lippmann dashed off a preface for it not long after Miss Saunders made a trip to Washington to induce the Lippmanns’ black standard poodle, Brioche, to stop biting the columnist’s secretaries. “To [those] who cannot or will not train their own dogs, [this] book ought to carry conviction that for dogs, as well as for others, education and discipline are not accompaniments of tyranny but are necessary to the pursuit of happiness,” Lippmann wrote resoundingly.

Along with other wide-awake modern educators, Miss Saunders has recently begun employing audio-visual aids in her teaching. Her most successful effort in this branch of instruction has been a series of three 16-mm. films produced, in both black-and-white and color, by United Specialists, Inc., a firm in which she is associated with Louise Branch, who owns it and who, happily, is not only a fellow poodle fancier but a photographer. The three films, collectively also called “Training You to Train Your Dog” and billed by the producers as a “five-bark picture, a real bow-wow!,” are designed to drive home the points made by Miss Saunders’ manual, and they are available separately or in complete sets, the cost in the latter case being two hundred and ten dollars for a black-and-white version or five hundred and seventy dollars in color. Puppy Trouble, the first of the series, covers, as set forth in its subtitle, the “Kindergarten and Grade School Training Stage” of a dog, and the voice of Helen Hayes, a poodle owner herself, has been dubbed in, expressing the presumed thoughts of the starring puppy, who, it was found, could not be relied upon to respond vocally at the proper moments and was not quite as comprehensible even when he did. “Some very cute little touches,” as Miss Saunders described them over the radio not long ago, resulted from this collaboration. “In one scene, where the puppy was getting his first bath,” Miss Saunders went on, “Miss Hayes made her voice shiver so realistically you could almost hear the little fellow tremble.” The second United Specialists film, called Basic Obedience Instruction and subtitled “High School and Prep School Training Stage,” and the third, called Advanced Obedience Instruction and subtitled “College and University Training Stage,” have Lowell Thomas on their sound tracks, explaining the steps by which Obedience Training may lead to the granting of degrees represented by initials, analogous to B.A., M.A., and Ph.D., affixed to a dog’s name. Basic Obedience Instruction depicts Miss Saunders and one of her favorite poodles demonstrating to a number of more or less intelligent-looking dogs and their owners the requirements for the degree of C.D., or Companion Dog—the lowest rung on the academic ladder. These include the heel on leash, the heel free, the recall, the long (one-minute) sit, and the long (three-minute) down. As might be expected, the third film, leading through the halls of higher learning, covers far more esoteric accomplishments, such as the retrieve on flat, the retrieve over obstacle, the speak on command, and the seek-back for lost article, by which the pupil progresses up the ladder to the degree of C.D.X. (Companion Dog, Excellent), then to U.D. (Utility Dog), and finally to U.D.T. (Utility Dog Tracker).

The “Training You to Train Your Dog” films are distributed to the public, usually at a nominal charge, by a number of rather disparate organizations, including the American Meat Institute and the American Museum of Natural History, which buy the reels from United Specialists. One of the distributors, the Gaines Dog Research Center, maintained by the makers of Gaines dog foods, estimates that through its facilities alone at least five hundred thousand people in this country are privileged each year to hear Miss Hayes whimpering in her imaginary tub and to watch one of Miss Saunders’ talented poodles discriminating, at the command of his mistress, between a scented and an unscented gardening glove. These performances have undoubtedly proved instructive to a further, unestimated number of people in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, Cuba, Mexico, Brazil, and Venezuela, where the movies have also been distributed. The most recent request for them from abroad came in to United Specialists, to the gratification and mystification of everyone there, from the Rajkumar Preatum Sherjung, of Bijnor, United Provinces, India, who demanded the whole works, Puppy Trouble and all.

Obedience Training is of Teutonic origin, and because it involves not only a good deal of canine regimentation but downright physical coercion on the part of the handler, who uses a choke collar to induce a dog to fall in with his wishes, its opponents frequently claim that its ranks consist of what they describe as Prussian types, or people desirous chiefly of imposing their wills forcibly on others. Obedience trainers, these detractors say, are imbued with top-sergeant, or bulldog, tendencies, to a man, or woman. But though Miss Saunders is considered in dog-fancying circles to be the embodiment of what is reverently termed “trainer personality,” there is little in her manner to suggest the top sergeant and there is absolutely nothing of the bulldog about her. A dog-show official who is at his most articulate within his own very special frame of reference once said of Miss Saunders that she combines all the commendable qualities, both physical and temperamental, that are customarily associated with the terrier group—the slimness and stamina of the wirehair, the pleasing facial contours and limpid eyes of the cairn, the activity and gameness of the Border, and the amiability of the Dandie Dinmont—an opinion concurred in by the majority of her admirers but highly disconcerting to a minority who hold that Miss Saunders, since she is a confirmed poodle fancier, should bear a resemblance to her favorite, rather than to an alien, type of dog.

One attribute that Miss Saunders shares with no breed of terrier is her voice, which is low and husky. It is seldom raised in anger, but there is a perceptible undercurrent of annoyance in it when she’s dealing with dog owners en masse. This is especially noticeable when she is confronted, in one of the various armories and gymnasiums in which she works, by a bunch of would-be trainers who, to judge, by their actions, couldn’t impose their collective wills on a tame mouse. At the start of such a class, Miss Saunders usually manages to employ the most moderate of the three tones of voice she advocates for Obedience Training; namely, the coaxing. “Let’s try to improve just a little on our sit-stay this week,” she’ll say into a portable microphone she uses, addressing the thirty-odd dog owners lined up in front of her with their pets (ranging in size from Great Danes to Chihuahuas), each of which is stationed, in conformance with Obedience protocol, beside his owner’s left knee. As the owners timidly beseech their charges to plunk themselves down on their haunches by way of participating in the sit-stay, Miss Saunders emits a gusty sigh, well amplified by the microphone, and resorts to the second, or demanding, tone of voice. “Come on, see to it your dogs sit!” she says firmly. “String them down on that leash. Who’s supposed to be training who around here, anyway?” When, in consequence of resisting a good deal of tugging on choke collars, most of the dogs have decided that it’s in their best interests to sit down, the owners drop their leashes and back gingerly away to a distance of fifteen or twenty feet, uttering what they fondly believe to be forceful requests to the dogs to stay put. At this point, two or three representatives of the more flighty breeds are likely to begin frolicking about the arena, and Miss Saunders is obliged to fall back on the third, or commanding, tone. “Bring your dogs back! Make them sit! Snap them down! See that they stay!” she shouts lustily into the microphone. “Put a little conviction in your voice for a change! No diplomas for you if you can’t learn a simple exercise like this!”

Although this threat obtains results in most cases, each class is very apt to include at least one overwrought lady dog owner who not only is unable to make any impression whatever on her charge but may even burst into tears as she pursues him around the floor. When this occurs, Miss Saunders sets her microphone down with a crash, mutters “My goodness sakes!”—her strongest exclamation—and strides forward to take over the delinquent dog. Seizing his leash, she gives it a brisk tug, remarks matter-of-factly that the dog isn’t boss around the place, as he seems to think, and repeats the sit-stay command. Sometimes a brief clash of wills ensues. More often, the dog gives Miss Saunders a speculative look and quietly falls in with her wishes, leaving his owner with the suspicion that something occult has taken place in her presence.

The effectiveness of Miss Saunders’ trainer personality, as manifested in her direct dealings with dogs, is difficult even for experts to explain, but it is generally conceded that she is the fortunate possessor of what those in the know refer to as “dog hands.” This attribute, they say, is a matter of rapport, of which, as the late Josef Weber, of Princeton, New Jersey, one of the most noted of all German-born trainers in this country, said in a still widely quoted apothegm, “It yoost goes down the leash.” In addition to being endowed with dog hands, or leash rapport, Miss Saunders is said to be able to anticipate to an uncanny degree the way a dog will act in almost any set of circumstances. In this way she averts many of the crises—dogfights, for example—that often harass less intuitive trainers. Despite her talent for keeping intellectually one jump ahead of a dog, however, she hasn’t been able to wholly avoid one perennial training hazard—plain dogbite. At one time or another, representatives of practically every recognized breed, and quite a few mutts, too, have sunk their fangs into various portions of Miss Saunders, mistaking her, possibly, for an owner devoid of trainer personality. From a canine point of view, the results of these onslaughts have been unrewarding. “A dogbite to Blanche is as a mosquito bite to you or me,” a man from the A.S.P.C.A. told a dog owner who was taking a breather during a training session one evening not long ago. By way of example, he cited an occasion on which Miss Saunders was driving him and a dog of hers home after a class. As she stopped for a traffic light, she complained mildly of a disagreeable tickling sensation in one foot. When they reached his home, she got out and examined her foot under a street light. She discovered that the toe of one of her substantial leather brogues had been gnawed open and a wound inflicted that would have disabled the average person for a week. Miss Saunders’ only reaction was a relatively casual “My goodness sakes!” Then she bade the A.S.P.C.A. man a polite good night and leaped back into her car.

As Miss Saunders frequently points out in her training manual, the element of surprise is an all-important one in the master-dog relationship. It is also one of which she has always taken fullest advantage. In this field, as a trainer, she presupposes a good deal of ingenuity, alertness, and agility on the owner’s part. If a dog is too vocal, for instance, and sets up a clamor the minute the owner leaves the house, Miss Saunders advises the owner to put on his hat and coat, shut the dog in the living room, stride to the outside door, slam it, and then sneak back noiselessly to the living-room door. “At the first sound [the dog] makes, call out, ‘Stop that!’ ” she counsels. “This may come as such a surprise that he will probably be quiet the rest of the day, trying to figure out how you got back into the house without his knowing it.” Miss Saunders also recommends some rather unusual items of equipment for startling dogs out of their shortcomings and making them ponder the singular requests of mankind. Among these are mousetraps (to be placed on sacrosanct chairs or couches), short lengths of chain (to be tossed at a dog’s hindquarters if he barks when the doorbell or telephone rings), carriage whips (to be used in breaking dogs of chasing automobiles), and BB guns (to be aimed, it should be noted at once, not at but away from an erring pet). Illustrating the use of a BB gun, Miss Saunders tells in her manual of a distressingly loud-mouthed poodle who was an inmate of a kennel she once ran. “I crept inside the kennel with a BB gun,” she recalls. “For fully twenty minutes I stood in total blackness with the BB gun pointed toward the wooden door of the pen.… Then when [the dog] decided it was time to begin [barking] again I pulled the trigger. In the dead of night the little pellet sounded like an exploding firecracker when it hit the door. From then on there was perfect silence.”

In the hands of an impetuous or highly nervous dog owner, a BB gun might well turn out to be a dangerous, or even lethal, weapon. In Miss Saunders’ hands, never. She has been distinguished for both her marksmanship and her aplomb with firearms ever since the memorable day when, at the age of fifteen, she first hefted a rifle. As she recalls the incident, she was summoned out of a high-school history class and asked to pinch-shoot for a friend in a rifle match. After taking only two practice shots, both of them bull’s-eyes, she entered the match, and wound up with two firsts—high score for girls and high score for boys and girls. To Miss Saunders’ classmates, this was not a violently surprising accomplishment, for she had already established herself as proficient in sports, having earned a position on five of the school’s six championship athletic teams for girls. It is Miss Saunders’ suspicion that her athletic aptitude was a result of trying to hold her own in a household in which the other offspring consisted of seven older brothers and one older sister. She became a member of this top-heavy brood on September 12, 1906, in the town of Easton, Maine, where her father, the Reverend Abram Saunders, was the Baptist minister. After his death, in 1916, the family moved to Detroit, where she attended high school, ending up with excellent marks as well as a shelfful of trophies. Upon graduating, in 1924, she got a summer job on a small farm near Brewster, in Putnam County, New York, owned by Ethel Perrin, a family friend and the founder of the department of physical education in the Detroit public-school system. Tending Miss Perrin’s livestock proved so congenial to Miss Saunders that she decided to learn more about the subject and, accordingly, enrolled that autumn in Massachusetts Agricultural College, which is now a part of the University of Massachusetts. There she majored in animal husbandry and poultry raising, and took side courses in engineering, carpentry, and automobile repairing. As part of its curriculum, the college insisted that its students take jobs on farms for at least six months of each year. Such was the local reputation Miss Saunders had achieved while working on the Perrin place that she had little difficulty finding a berth for herself as first in command of a fifty-acre farm in the vicinity of Brewster.

“What other tricks does he need?”

During the next ten years, while still an undergraduate and afterward, Miss Saunders worked on farms in and near Putnam County. This period of her life is recorded in considerable detail in several plump photograph albums that she treasures. A few of the snapshots in them show Miss Saunders—wearing overalls and looking handsome, healthy, and supremely contented—perched atop this or that item of farm machinery. Most of the pictures, however, are of animals, including calves named Precious, Marjorie, Sylvia, and Edna; Jerushe, a very photogenic shoat; Muffit, a stolid work horse; and innumerable anonymous milch cows—all of which, she feels, were in some measure responsible, by giving her a working knowledge of animal psychology, for her present skill in handling dogs. She believes, for example, that a flock of White Leghorns, shown in the albums in their various stages of development, laid the foundation for her ability to move casually and almost soundlessly among high-strung dogs. Most often, when looking through the albums, Miss Saunders turns to the photographs of some Boston terriers she encountered during her farm training, to whom she taught such tricks as begging, jumping over sticks, and balancing tennis balls on their noses. She frequently says that although she’d never heard of Obedience work at the time, these terriers—notably one named Tagalong, a performer of the highest calibre—provided her with the equivalent of a kindergarten, or even a grade-school, course in the subject.

Regrettably, there’s no photograph to record the afternoon, in the autumn of 1934, when Miss Saunders unknowingly took the plunge into what was to be her lifework, and experienced in the process the first faint intimations of her affinity for poodles. “I was working up in a haymow on a farm near Brewster that afternoon when a car with a rather large, intelligent-looking dog and a woman in it pulled into the barnyard,” she has since recalled. “I came running down, and the dog was introduced to me as Tango of Piperscroft, an apricot standard poodle. I said, ‘You mean that’s a poodle? I thought they were horrid little white things with runny eyes.’ ” When the matter of Tango had been settled, Miss Saunders learned that her bipedal caller was Mrs. Whitehouse Walker, of Bedford Hills, who owned the poodle and was, indeed, the leading exponent of standard poodles in this country. Now she was pioneering in Obedience work with Tango and the other poodles she had in her poodle kennel, the Carillon, at Bedford Hills. Her visit to the Brewster barnyard was prompted by the fact that she had advertised in the Rural New-Yorker for a kennel maid at twenty dollars a month, and Miss Saunders had answered the ad. “I must have been getting a little bored with heavy animals, I guess,” Miss Saunders says. “Anyway, until I saw that ad, I’d never thought of working with dogs. If anyone had suggested it, I’d have said, ‘My goodness sakes, not me!’ Of course, I didn’t know it then, but Tango was a very important dog—the granddaddy of Obedience in America.”

The granddaddy of Obedience in America, important though he was, wasn’t a perfect physical specimen, being a shade too wide in the rear, but he was presentable enough to overcome Miss Saunders’ anti-poodle bias. The week after Tango and Mrs. Walker called on her, she went to help out around the Carillon, and within a month she had been elevated to the role of kennel manager. During that period, her personality underwent the sort of metamorphosis that Obedience people consider one of the most valuable by-products of their specialty. Commenting admiringly on this, Mrs. Walker said the other day, “When Blanche first came to the Carillon, she was a shy, demure little thing, without much self-confidence. But as soon as she’d worked a couple of weeks with Carillon Epreuve—Glee, for short, and the most nervous and timid of all our bitches—she simply blossomed out. That’s the beauty of Obedience. It gives one poise. Takes one out of oneself. Glee was completely transformed, too. She ended up as the first dog in the United States, of any breed, to get her C.D., her C.D.X., and her U.D.”

Having Miss Saunders to run her kennel for her left Mrs. Walker free to devote her full energies to alerting the dog fanciers of America to the merits of Obedience—a task of some magnitude, for at that time most people on this side of the Atlantic were under the impression that the only reasonable goals of formal dog training were police work, sheepherding, hunting, and retrieving. Only a few months before the arrival of Miss Saunders at the Carillon, Mrs. Walker had taken her first step toward advancing her theory that a dog should be well behaved as well as utilitarian by giving an informal demonstration of Obedience on the lawn of her father’s estate, in Mount Kisco. Not long after that, she had succeeded in talking the officials of the North Westchester Kennel Club into letting her put on a similar affair as a part of their annual all-breed show. The small group of dogs and owners starring in this exhibition were rather uncertain about what they were up to, for their training was based solely on Mrs. Walker’s hazy recollection of some Obedience tests she had once watched in England, but even so they walked away with the show. “The spectator appeal was so fantastic that nobody paid any attention to the judging of the breeds,” Mrs. Walker afterward reported triumphantly to a friend.

Inspired by this coup, Mrs. Walker left Miss Saunders in charge of the kennel and hopped the next boat for England, where she headed straight for Tango’s birthplace, the Piperscroft Kennels, near Horsham. Here Mrs. Grace E. L. Boyd, the owner of the kennels, put her star Obedience dog, King Leo of Piperscroft, through his paces for Mrs. Walker’s edification. Next, Mrs. Boyd took her guest to meet a neighbor, a Captain Radcliffe, who had been influential in introducing Obedience Training tests into England from Germany. Under the Captain’s guidance, Mrs. Walker mastered the subject, from hup to pfui, in about three weeks. Then she hopped a boat home. During the crossing, she stayed in her berth, outlining in her mind the first set of American Obedience rules. These were modifications of the English rules, which, numbering among their requirements such feats as scaling walls, retrieving objects over six-foot hurdles, and refusing food from strangers, Mrs. Walker considered too exacting. When she got home, she set about with renewed vigor serving as an evangel of Obedience and soon succeeded in stirring up so much interest among dog fanciers in this country that she was unable to deal singlehanded with the requests for information that inundated Bedford Hills. She was relieved to find that Miss Saunders had become infected by her enthusiasm and was able to take over all the correspondence while Mrs. Walker was in the field plugging her hobby.

In 1936, Mrs. Walker gathered a number of small East Coast Obedience groups she had helped organize into the Obedience Test Club, with headquarters at Bedford Hills, and introduced its members to the intricacies of a scoring system she had worked out for Obedience trials—the exhibitions, most often held in connection with bench shows, that determine the eligibility of the competing dogs for degrees. That same year, the officials of the American Kennel Club, who had been viewing this newfangled aspect of the dog business with skeptical aloofness, apparently came to the conclusion that their organization was better equipped than was the relatively insignificant Obedience Test Club to handle all the red tape connected with Obedience records and scoring systems and with the dispensing of degrees. They therefore announced that the A.K.C., whose official sanction carried almost overpowering weight among dog fanciers, would recognize Obedience Training, but only if it was given by clubs that paid the organization a fee of two hundred and fifty dollars. To the chagrin of those who had got in on the ground floor of Obedience, the A.K.C. declined to recognize the accomplishments of dogs who had already forged ahead in Obedience Test Club classes, which made it necessary for those luckless animals to re-enroll as novices and compete all over again, under a slightly different scoring system. The A.K.C.’s appearance on the scene also had the effect of automatically disqualifying any dog with a bar sinister in its background from earning recognized degrees, no matter how talented it might be. The unfortunate owners of dogs in this category nonetheless managed to keep their chins up, and continued to form Obedience clubs—unsponsored ones, which awarded a tactfully worded certificate rather than a degree. A few years later, their morale was raised considerably when a woolly-coated little dog named Squeaky, a stray adopted by Dr. Mary Julian White, then of New York and now a psychiatrist practicing in Washington, was shown on the cover of the American Kennel Gazette, along with two dogs of unquestionable ancestry, in a photograph taken during an intermission in an Obedience demonstration put on by Miss Saunders in Rockefeller Plaza. Since Squeaky was, and still is, the only mutt ever to be thus honored by the magazine, the photograph caused a furore which hasn’t yet died down completely. Nowadays, the staff of the Gazette is noncommittal when questioned about l’affaire Squeaky, but some defenders of the publication’s editorial integrity claim that Squeaky is, to the expert eye, no mutt at all but a representative of a rare Tibetan breed, the Lhasa Apso. (Squeaky’s owner, too, likes to think of him as a Lhasa, but, as a psychiatrist, feels obliged to admit that her thinking may be wishful.) Miss Saunders, however, who originally trained him, is an outright dissenter. “Now, look, that dog’s no more Lhasa than I am,” she said the other day. “Last month, in Canada, I met up with a real Lhasa, and he didn’t look a bit like Squeaky. When he lived in New York, Squeaky used to be clipped to look sort of like a schnauzer, but he isn’t that, either. He’s just a terribly talented mutt, and that’s how he got into my Rockefeller Plaza demonstration, and met up with that photographer.”

“May I keep my collar on?”

Dazed but not done in at having their Obedience baby taken out of their hands by the A.K.C., Mrs. Walker and Miss Saunders, a resilient pair, swiftly began adjusting themselves to the new order of things. One of the marked advantages of being nestled under the maternalistic wing of the A.K.C., they realized, was the circumstance that from that time on Obedience trials could be held without any quibble at all in conjunction with A.K.C.-sponsored bench shows, the most fertile possible spots for long-range Obedience proselytization. In the matter of purebreds versus crossbreeds, both women were, and are, leniently disposed toward mutts; Miss Saunders, in fact, in later years, after her prestige as an Obedience trainer was such that she could get along without the cachet of A.K.C. backing, pretty much threw in her lot with the A.S.P.C.A., which makes no distinction between purebred and mongrel and can therefore award only certificates, and the majority of the classes she conducts today are held under its auspices. At the time, however, as thoroughbred-poodle fanciers and breeders, both she and Mrs. Walker had to admit that the A.K.C.’s discriminatory stand had its points, and before long the Obedience Test Club’s literature was proclaiming that its ultimate aim was “to demonstrate the usefulness of the purebred dog as the companion and guardian of man and not the ability of the dog to acquire facility in the performance of mere tricks.” In order to further this aim, Mrs. Walker and Miss Saunders embarked, in the fall of 1937, on a trek that has become legendary in the dog world. Rigging up a twenty-one-foot trailer with all the installations of a well-run dog-diet kitchen, they hitched it to Mrs. Walker’s car and set out in the company of Glee and two other blue-ribbon poodles—Ch. Carillon Joyeux and Ch. Carillon Boncœur—to give their demonstrations in communities where, as Miss Saunders puts it, “the word ‘obedience’ had never been heard before.” These included most of the focal spots on the Southwestern dog-show circuit—Wichita Falls, Dallas, San Antonio, Houston, Galveston, Fort Worth, and Los Angeles. It was a lighthearted trip, as well as a successful one from a missionary point of view. “In that part of the country, dog people are rather like circus people,” Miss Saunders later told some friends. “Just a big, happy family. On their way to shows, and going home, they shouted to each other from car to car, and often pulled up by the side of the road to compare notes on their dogs.”

Ten weeks and some ten thousand miles later, the peripatetic kennel, its personnel intact, returned to Bedford Hills, greatly to the relief of several of the community’s human inhabitants, who had considered the venture a perilous one and who now gathered about to shudder delightedly over the two women’s accounts of its hazards, such as a Texas sandstorm that clogged all the drains in the trailer, and encounters, in several remote spots, with hoboes who, peering in the trailer’s windows, reeled back when confronted by the merry faces of Boncœur, Glee, and Joyeux. As a more or less direct outcome of the trip, the number of Obedience trials held in conjunction with dog shows doubled within the next few months. The long-range results of the two travellers’ efforts were recently pointed up in some figures released by the A.K.C., showing that since 1936 it has awarded to representatives of a hundred and eight of the hundred and eleven officially recognized breeds 6,550 C.D.s, 1,680 C.D.X.s, 460 U.D.s, and 296 O.D.T.s, and that in all, during that time, well over fifty thousand purebred dogs have competed in Obedience trials. While Obedience people regard these statistics as impressive, they also see in them a challenge to intensify their campaigning, especially when they reflect upon the fact that the total number of dogs in the United States is somewhere around twenty-two million, about five million of them purebreds and the rest kitchen cousins, or mutts.

Not long ago, the editor of Dog World—“If It’s about Dogs, Write to Dog World”—explained to a reader, who had taken him at his word, that Obedience trials in this country have proved to be “a vitamin for the dog-breeding and showing field.” He might well have added that Miss Saunders’ achievements both in Obedience work and in poodle breeding are an almost perfect case in point. At the time Miss Saunders took over as manager of the Carillon, poodles were comparatively rare in America; only a hundred and thirty-four of them—possibly a third of the country’s total—were registered in the A.K.C.’s studbook. As a pupil, and then as an instructor, in Mrs. Walker’s Bedford Hills Obedience Training classes, and later as a judge at Obedience trials, Miss Saunders became convinced that poodles constitute an eminently satisfactory breed for Obedience work, owing to two pronounced traits—their anxiety to please their masters and their intelligence, a term rather loosely applied by breeders to dogs who take readily to training and are able to retain what they have learned. Although it is impossible to put a finger on all the factors that determine the popularity of a given breed of dog, it is at present generally agreed that the increasingly frequent and successful appearances of poodles in Obedience trials in this country have had a decidedly tonic effect on their sale. By 1944, the number of poodle registrations had risen to 465, and by 1946 to 1,186; last year, the total was 3,195. A while ago, in reply to a letter inquiring about the total number of poodles now owned in this country, and, more specifically, in New York City, Arthur Frederick Jones, editor of the American Kennel Gazette, wrote, “I would estimate that now living in the United States there are about 14,000 Poodles of all sizes. This is estimated on the registrations over the last ten years, Poodles not usually dying too young. It would be practically impossible to estimate the number in New York City, other than to say that, aside from Southern California, and a few in the Middle West, the metropolitan area contains the bulk of America’s Poodle population.”

In 1943, Miss Saunders felt that the time had come to strike out on her own. By then, it was obvious that a local, and possibly a national, poodle vogue was in the making. At the instigation of Mrs. Walker, who had decided to close the Carillon, because of the difficulties of keeping it going in wartime, Miss Saunders came to New York and rented a house in the East Fifties, where she opened an establishment for the care and training of poodles. The shingle she hung out bore the Carillon name, bequeathed her by her former employer. She also brought with her, as an additional gift from Mrs. Walker, a poodle bitch named Ch. Carillon Colline—better known as just Colline—who was to be entrusted with the task of perpetuating the Carillon strain. Within a short time, the new Carillon, where Miss Saunders clipped, shampooed, manicured, boarded, and trained poodles (along with an occasional maverick from some alien breed), became immensely successful; its clientele included the pets not only of some of the most prosperous people in the city but of several well-known out-of-towners, among them some Wilmington du Ponts, who flew a number of poodles here regularly by private plane for their Carillon appointments. From the point of view of Colline, however, an urban base of operations offered serious disadvantages when offspring began to arrive, just as it has to many another young matron. This situation was remedied in 1946, when Miss Saunders and her photographer friend and business associate, Miss Branch, while in the throes of planning the first of their Obedience pictures, hit upon the idea of setting up yet another Carillon kennel, on an estate Miss Branch shares with other members of her family, in Pawling. By this time, Miss Saunders was working ten hours a day in her Manhattan establishment, in addition to running training classes for the A.S.P.C.A. once a week and judging Obedience trials on the side, and was therefore able to devote only weekends to the development of the Pawling project. Even so, she contrived to find time to draw up the architectural plans for the kennel, which started on a small scale but has been expanded over the years to accommodate sixty poodles, and which features such amenities of canine living as an electric dishwasher in its kitchen and ultraviolet lights over its whelping pens. A month or so ago, she expanded this operation by buying a ten-acre place near Bedford, which she is also calling the Carillon and where she plans to keep the kennel’s puppies. The show stock will remain in Pawling.

Colline, now an extraordinarily agile matriarch of fourteen, no longer has any active duties around the Carillon, but she roams the premises with an air of marked, and justifiable, smugness. Occasionally, she is accompanied on her rambles by the most illustrious of all her offspring, Ch. Carillon Jester (C.D., C.D.X., U.D.T.), a handsome black standard poodle whose entire life has been consecrated to the cause of Obedience. Ever since he first posed, in his late puppyhood, for the illustrations for Miss Saunders’ training manual, Jester has been in the public eye almost without surcease, performing in Obedience movies, barking fetchingly at Miss Saunders’ request on radio programs, heisting dumbbells on Faye Emerson’s television show, and tracking down gardening gloves, handkerchiefs, and other items of Obedience paraphernalia at large-scale Obedience exhibitions in such places as Madison Square Garden and Yankee Stadium. In the opinion of Obedience people, gatherings for the observance of National Dog Week and Be Kind to Animals Week would be hollow occasions indeed were it not for the presence of Jester, who inevitably has his audience in his pocket.

“I can’t explain it. I see that guy coming up the walkway and I go postal.”

The advanced state of development to which Obedience Training has succeeded in bringing Jester’s talents is readily explained in the light of the evolution of his breed. Over the centuries, poodles have been distinguishing themselves for their savoir-faire in the hunting field, in circuses, on the stage, and in the laps of royalty. Poodles were once primarily used as retrievers of waterfowl, as Miss Saunders is about to point out in what she describes as “an unusually straight-from-the-shoulder dog book,” on which she is collaborating with Mrs. John Cross, Jr., the dachshund-fancying wife of the bench-show chairman of the Westminster Kennel Club. The book will also scotch the widely held notion that poodles originated in France. Actually, they originated in Germany; their name is derived either from the German Pudel, meaning puddle, or from puddeln, to splash in water. The poodle’s elaborate clip, which has been the target of much facetious comment from the uninitiated, dates back to its retrieving days, when it was adopted as a practical measure, to keep the animals from sinking under the weight of their coats as they dived into rivers or lakes to retrieve birds. Shortly before the French Revolution, poodles were taken up wholeheartedly by the ladies of the court at Versailles. As a result, the breed attained an aura of preciousness that still clings to it, obscuring what Miss Saunders feels is its true utilitarian worth. She regards it as lamentable that a lot of latter-day poodle owners have persisted in taking a frivolous attitude toward their pets, especially in the matter of discipline. “Of course [my Miss Matilda] is spoiled,” Mrs. James Lowell Oakes, Jr., blithely admits in The Book of the Poodle, one of the many recently published volumes devoted to rhapsodic appraisals of the breed. “She is going to school and learning Obedience Training … but I do not want her ever to lose her love of people. I do not want her to stop jumping up on the back of our love seat or barking at our car.”

Whimsical and overindulgent dog owners, although a notably free-spending group when it comes to providing comfort for their pets, nevertheless cause Miss Saunders a good deal of anguish. She suffers greatly in this respect at nearly all the Obedience Training classes she conducts, and perhaps most of all on those nights when she presides over a series of classes open only to poodles, sponsored by the Poodle Obedience Training Club of Greater New York, an organization of some seventy-five poodle fanciers, each of whom is convinced that his dog is superior on every count to all other poodles. As Jester’s owner, Miss Saunders is able to ignore and even to smile at this communal fantasy, but she has found it extremely difficult to overlook some other, far more serious misapprehensions that members of the group cling to. On one recent all-poodle evening, for example, when the class convened in the gymnasium of the Washington Irving High School, on Irving Place, it became apparent as the novice division paraded before her, with only three more sessions to go before graduation, that the owners had been cherishing the illusion that their dogs were far too smart to need to bother their heads about the homework assigned them. “My goodness sakes!” Miss Saunders said rather early in the evening. “Where’s this class been for the last four weeks? My all-breed class last night had only had a couple of lessons and their dogs heeled perfectly, on and off leash. Don’t any of you ever work your dogs at home?”

“It’s been raining a lot,” explained the owner of a gray miniature with a red ribbon on its topknot.

“So what?” Miss Saunders said. “Your poodle can heel in the living room, can’t he?”

Meanwhile, at the far end of the gymnasium, where a number of folding chairs had been set out, the members of the advanced, or utility, division were assembling. As Miss Saunders continued with the novice lesson (“Turn! Turn! Snap! Praise! Command when you start! Get those leads slack!”), one of the most enthusiastic of the local poodle fanciers, Count Alexis Pulaski, made an impressive entrance. In his retinue were Ch. Pulaski’s Masterpiece (U.D.), Deauville Coquette, and Pulaski Master’s Pinocchio, three of his finest gray miniatures; their handler, Miss Lucy Copestake; and Miss Dorothy Dorn, head of the dog department at Hammacher Schlemmer, who was staggering under the weight of several large suit boxes, which turned out to contain various articles of canine apparel. As the newcomers seated themselves, Ch. Carillon Jester, tethered nearby, set up a prolonged howl.

“What goes on over there?” Miss Saunders inquired irritably from her end of the gymnasium.

“Jester’s teaching my Cocoa bad tricks,” complained the young and pretty owner of a brown standard two seats away from the Count.

“Well, I can’t believe my ears,” Miss Saunders said. “Jester never howls unless he’s interested in being a daddy. Slap his nose, somebody. Now, class, make your corrections again, and make them severe!”

The novice trainers obediently shouted “Heel!” at their dogs, with various degrees of conviction, and on the sidelines Miss Dorn opened the largest of the suit boxes and lifted out some poodle-size navy-blue serge sailor collars, ornamented with white rick-rack braid and red stars.

“Adorable!” cried Cocoa’s owner.

“My dogs are going to wear these collars at next week’s cocktail party at the Coq Rouge,” the Count explained to her. “Masterpiece is to be guest of honor. Did you know he makes about ten thousand a year in stud fees?”

“No! Really?” exclaimed the young woman.

“Less noise over there!” Miss Saunders called bitterly into her microphone. “This isn’t a tea party, it’s a class,”

“We’ll try on Coquette’s costume first,” said Miss Dorn in a stage whisper, and proceeded to squeeze that sleepy and reluctant animal into a black velvet jacket, ornamented with ermine tails. “She’s gained a good deal of weight,” she added doubtfully.

“Try to make her walk,” said the Count. “I want to see the effect.”

“If the buttons are moved over, she can get away with it,” Miss Dorn assured him.

“We’ll diet her,” the Count said.

“If there isn’t less noise over there, somebody’s going to have to leave,” Miss Saunders said balefully as Jester commenced howling again.

“I don’t think you’d better work Masterpiece tonight,” the Count said to Miss Copestake as the novice division began to straggle off the floor. “He got a little overexcited at the photographer’s today.”

“O.K.,” Miss Copestake replied.

“If things go like this next week, we won’t have any graduation, I warn you!” Miss Saunders shouted after her retreating novices. “Now I’d like the advanced class out here, if I can manage to have a little peace and quiet.” Then, slamming down her microphone on a table in front of her and lighting a cigarette, she remarked sotto-voce to a friend standing nearby, “Well, poodles are intelligent, anyway. I often like to remind myself of that.”

| 1951 |