Rin Tin Tin was born on a battlefield in the Meuse Valley, in eastern France, in September, 1918. The exact date isn’t certain, but when Leland Duncan found the puppy, on September 15th, he was still blind and nursing, and was nearly bald. The Meuse Valley was a terrible place to be born that year. In most other circumstances, the valley—plush and undulating, checkered with dairy farms—would have been inviting, but it rolls to the German border, and in 1918 it was at the center of the First World War.

Lee Duncan was a country boy, a third-generation Californian. One of his grandmothers was a Cherokee, and one grandfather had come west with Brigham Young. The family ranched, farmed, scratched out some kind of living. Lee’s mother, Elizabeth, had married his father, Grant Duncan, when she was eighteen, in 1891. Lee was born in 1893, followed, three years later, by his sister, Marjorie. The next year, Grant took off and was never heard from again. Lee was a great keeper of notes and letters and memos and documents. In thousands of pages, which include a detailed memoir—a rough draft for the autobiography he planned to write and the movie he hoped would be made about his life—there is only one reference to his father, and even that is almost an aside.

After Grant abandoned Elizabeth, she was unable to care for her children. She left them in an orphanage in Oakland. Neither she nor the children knew if they would ever be reunited. It wasn’t until three years later that she would reclaim them.

In 1917, Duncan joined the Army. He was assigned to the 135th Aero Squadron, as a gunnery corporal, and was sent to the French front. His account of this time is soldierly and understated, but he vividly recalled the morning of September 15, 1918, when he was sent to inspect the ruins of a German encampment. “I came upon what might have been headquarters for some working dogs,” he wrote. As he strolled around, he saw a hellish image of slaughter: about a dozen dogs, killed by artillery shells. But hiding nearby was a starving, frantic German shepherd female and a litter of five puppies.

From the moment he found the dogs, Duncan considered himself a lucky man. He marvelled at the story, turning it over like a shiny stone, watching it catch the light. He thought about that luck when it came to naming the two puppies he eventually kept for himself—the prettiest ones, a male and a female. He called them Rin Tin Tin and Nanette, after the good-luck charms that were popular with soldiers in France—a pair of dolls, made of yarn or silk, named in honor of two young lovers who, it was said, had survived a bombing in a Paris railway station at the start of the war.

In May, 1919, after the Armistice, Duncan returned to the United States. It would have been easier to leave the “war orphans” behind, but, he later wrote, “I felt there was something about their lives that reminded me of my own life. They had crept right into a lonesome place in my life and had become a part of me.” Before they reached California, however, Nanette developed pneumonia and died, and Duncan got another German shepherd puppy, named Nanette II, to keep Rin Tin Tin company. After Duncan had been back home for a while in Los Angeles, where Elizabeth was then living, he began to feel restless and anxious. He experienced spasms, probably as a result of his war service, and he found it difficult to work. His one pleasure was to train Rinty, as he called him, to do tricks.

By then, Rinty, a rambunctious, bossy dog, was nearly full-grown. He had lost his puppy fluffiness; his coat was lustrous and dark, nearly black, with gold marbling on the legs and chin and chest. His tail was as bushy as a squirrel’s. He wasn’t overly tall or broad, his legs weren’t particularly muscular or long, but he was powerful and nimble, as light on his feet as a mountain goat. His ears were comically large, tulip-shaped, and set far apart on a wide skull. His face was more arresting than beautiful, his expression pitying and generous and a little sorrowful, as if he were viewing with charity and resignation the whole enterprise of living.

German shepherds were a relatively new breed, and very new in this country, but their popularity was growing quickly. Duncan got to know other shepherd fanciers, and helped found the Shepherd Dog Club of California. He decided to enter Rinty in a show at the Ambassador Hotel, in Los Angeles. An acquaintance named Charley Jones asked if he could come along. He had just developed a type of slow-motion camera, and he wanted to try it out by filming Rinty.

Rin Tin Tin and a female shepherd named Marie were competing in a jump-off for first place in the “working dog” part of the show. The bar was set at eleven and a half feet. The judge and show officials gathered beside it for a close look. Marie took her turn, and flew up and over. Rin Tin Tin then squared off for his leap. “Charley Jones had his camera on Rinty as he made his jump and as he came down on the other side,” Duncan wrote. The dog had cleared the bar at almost twelve feet, sailing over the head of the judge and several others, and winning the competition.

Something about watching Rin Tin Tin being filmed stuck with Duncan. In the weeks that followed, he was seized by a desire to get the dog to Hollywood. “I was so excited over the motion picture idea that I found myself thinking of it night and day,” he wrote.

In 1922, Duncan married a wealthy socialite named Charlotte Anderson, who owned a stable and a champion horse called Nobleman. The couple had probably met at a dog or a horse show. Still, the marriage was curious. Duncan was good-looking and was always described as a likable man, but he spent all of his time with his dog. It’s hard to imagine him presenting an alluring package to a woman like Anderson, who was sophisticated, older than Duncan—he was twenty-eight, she was in her mid-thirties—and had been married before. It’s even harder to picture Duncan having a romantic life; he made no mention of it, or of Anderson, in his memoir.

Duncan’s devotion was to his dog. When he wasn’t training Rinty to follow direction—which he did for hours every day—he took him to Poverty Row, in Hollywood, where the less established studios were. The two of them walked up and down the street, knocking on doors, trying to interest someone in using Rinty in a film. This wasn’t as implausible as it might sound: in those years, bit players were often plucked from the crowds that gathered at the studio gates. Moreover, in 1921, a German shepherd named Strongheart had made a spectacular and profitable appearance in The Silent Call. Strongheart was the first German shepherd to star in a Hollywood film, and his grave, gallant manner and the still-novel look of German shepherds caused a sensation. The dogs were now as sought after in Hollywood as blond starlets. Duncan probably brushed past other young men with their own trained German shepherds, all inspired by Strongheart, as he went from door to door.

Then Duncan got a break: he secured a small part for Rinty in a melodrama called The Man from Hell’s River. Rinty—who is not in the cast list but is mentioned in the Variety review as “Rin Tan”—plays a sled-dog team leader belonging to Pierre, a Canadian Mountie.

In time, Rin Tin Tin made twenty-three silent films. Copies of only six of those films are known to exist today. The Man from Hell’s River is not among them. All we have is the movie’s “shot list,” which was a guide for the film editor. Parts of it read like a sort of silent-film found poetry:

Long shot dog on tree stump

Long shot wolf

Long shot prairie

Long shot dog runs and exits

Long shot deer

Long shot dog

Medium shot girl

Close-up shot little monkey.

And, at the end:

Med shot dog and puppies

Med close-up more puppies

Med shot people and dogs.

Rinty was soon cast in another film, My Dad, a run-of-the-mill “snow,” which is what silents set in wintry locations were called. It, too, was a small part, but, for the first time, he was given a film credit. In the cast list, he appeared thus:

Rin-Tin-Tin…………By Himself.

Finally, Duncan got through the door at Warner Bros. One of the smallest studios, Warner Bros. had been founded in 1918 by four brothers from Youngstown, Ohio, who set up shop in a drafty barn on Sunset Boulevard. That day, Harry Warner was directing a scene that included a wolf. The animal had been borrowed from the zoo and was not performing well. According to James English’s 1949 book, The Rin Tin Tin Story, Duncan rubbed dirt into Rinty’s fur to make him look like a wolf, and persuaded Warner to give Rinty a chance to try the scene. Rinty performed brilliantly, and Warner liked what he saw. He agreed to look at a script that Duncan had been working on for Rinty, entitled “Where the North Begins.” While writing it, Duncan had studied the dog’s facial expressions. He was convinced that Rinty could be taught to act a part—not just to carry a story through action but “to register emotions and portray a real character with its individual loves, loyalties, and hates.” A few weeks later, Duncan got a letter from the studio: Warner wanted to produce his screenplay and cast Rin Tin Tin in the lead.

Production began almost immediately, with Chester Franklin, an accomplished director, in charge. Claire Adams, Walter McGrail, and Pat Hartigan—silent-film stalwarts—were cast opposite Rinty. The film was shot mostly in the High Sierras. “It didn’t seem like work,” Duncan wrote. “Even Rinty was bubbling over with happiness out here in the woods and snow.” Rinty sometimes bubbled too much, chasing foxes into snowdrifts, and, once, attacking a porcupine, which filled his face with quills. Otherwise, Duncan was proud of the dog’s performance, which included a twelve-foot jump—higher than the one at the Ambassador Hotel.

To advertise the film, Warner Bros. distributed promotional material to theatre owners which included ads, guidelines for publicity stunts, and feature stories for local newspapers. The features were meant to make the filming of the movie seem almost as dramatic as the movie:

HUNGRY WOLVES SURROUND CAMP

Movie Actors in Panic When Pack Bays at Them

GREAT RISK OF LIFE IN FILMING PICTURE

THE MOVIES NO BED OF ROSES

Chester Franklin, Director, Tells Hard-Luck Story of Blizzard.

The publicity stunts, which studio marketing people referred to as “exploitation,” included suggestions that theatre owners “get a crate and inside it put a puppy or a litter of them” for the lobby (“You will be sure to get a crowd”); partner with a Marine recruiter and place signs outside the recruiting office saying “WHERE THE NORTH BEGINS AT THE [BLANK] THEATRE is a thrilling picture of red-blooded adventure. Your adventure will begin when you join the marines and see the world”; or, as one, titled “HOLDING UP PEDESTRIANS,” proposed, “Get a man to walk along the principal streets of the city stopping pedestrians and asking them the question, ‘Where Does the North Begin?’ and upon their answering (or even not answering) he can … tell them it begins at your playhouse.”

When Where the North Begins was released nationwide, Variety declared, “Here is a cracking good film for almost any audience.… It has the conventional hero and the conventional heroine, but Rin-Tin-Tin is the show.… A good many close-ups are given the dog and in all of them he holds the attention of the audience closely.” Another review praised Rinty’s eyes, saying that they conveyed something “tragic, fierce, sad and … a nobility and degree of loyalty not credible in a person.”

The Times was more ambivalent, and made the first comparison between Rin Tin Tin and Strongheart: “This dog engages in a pantomimic struggle that is not always impressive, at least not nearly as realistic as the work of Strongheart,” but adding that Rin Tin Tin “is a remarkable animal, with splendid eyes and ears, and he seems to be wondering what all this acting is about.” Motion Picture Magazine’s story “The Rival of Strongheart” went further, noting that Rin Tin Tin “is now competing with Strongheart for the canine celluloid honors.”

The film was a hit, earning more than four hundred thousand dollars. Strongheart had set the pace, but Rin Tin Tin had become a star. Thousands of fan letters were arriving at Warner Bros. each week. Where the North Begins was playing all over the country, and, as was typical with popular films, most theatres extended its run as long as people kept showing up; movies were such a new form of entertainment that a hit film was a spectacle, a national event that everyone wanted to view. Still, the movie wasn’t at the level of Strongheart’s The Silent Call, which had broken attendance records in Los Angeles, where it was shown eight times a day for thirteen weeks.

Most of the German shepherds who followed Strongheart and Rin Tin Tin in Hollywood had just a burst of fame and then were forgotten. Among the many dozens were Wolfheart and Braveheart, Wolfang and Duke; Fang, Fangs, Flash, and Flame; Thunder, Lightning, Lightnin’, and Lightnin’ Girl; Ace the Wonder Dog, Captain the King of Dogs, and Kazan the Dog Marvel. They played serious, heroic figures in films that, like them, are now mostly forgotten: Aflame in the Sky, Courage of the North, The Silent Code, Avenging Fangs, Fangs of Destiny, Wild Justice.

In real life, too, the dog hero was having its day. In 1923, Bobbie the Oregon Wonder Dog walked alone for six months from Indiana to Oregon, to find his owners; in 1925, a sled dog named Balto led a team carrying diphtheria antitoxin to Nome, Alaska, saving the town from an epidemic; in 1928, Buddy, the nation’s first Seeing Eye dog, began guiding a young blind man named Morris Frank.

Even so, Rin Tin Tin was singled out. He was praised by everyone from the director Sergei Eisenstein, who posed for a photograph with him, to the poet Carl Sandburg, who was working as a film critic for the Chicago Daily News. “A beautiful animal, he has a power of expression in his every movement that makes him one of the leading pantomimists of the screen,” Sandburg wrote, adding that Rinty was “phenomenal” and “thrillingly intelligent.” Warner Bros. got thousands of requests for pictures of Rinty, which were signed with a paw print and a line written in Duncan’s spidery hand: “Most faithfully, Rin Tin Tin.”

From the start, Rin Tin Tin was admired as an actor but was also seen as a real dog, a genetic model; everyone, it seemed, wanted a piece of him. He and Nanette, who often appeared onscreen as his “wife,” mated, and Duncan distributed the puppies among some of Rin Tin Tin’s most celebrated fans. Greta Garbo and Jean Harlow each owned a Rin Tin Tin descendant, as did W. K. Kellogg, the cereal magnate.

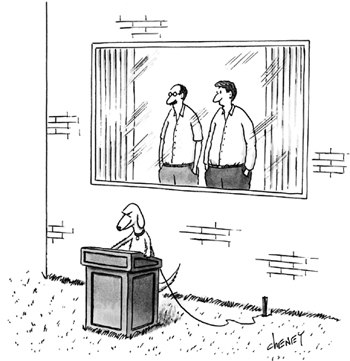

“Don’t you get it? It was never about the

stick—I sent you there to

find yourself.”

To promote Where the North Begins and subsequent movies, the studio sent Duncan and the dog on promotional tours around the country. They appeared at hospitals and orphanages, gave interviews, and visited animal shelters and schools. When describing a visit to one shelter, Duncan sounded as if he were telling the story of his own childhood through Rin Tin Tin. “Perhaps if I could have understood, I might have heard Rinty telling these other less fortunate dogs of how his mother failed in her terrific struggle to keep her little family together. Or how he, as a little war orphan, had found a kindred spirit in his master and friend, also a half-orphan.” Of course, Rin Tin Tin’s mother had actually succeeded in keeping her family together in the bombed-out kennel. It was Duncan’s mother who, for a time, had failed in her struggle.

In the evening, Duncan and Rinty would go to a theatre where a Rin Tin Tin movie was playing, and afterward come onstage. Duncan usually began by explaining how he had trained the dog: “There are persons who have said I must have been very cruel to Rinty in order to get him to act in the pictures,” especially in the scenes where the dog is shown “groveling in the dust, shrinking away, his tail between his legs,” which Rinty did in Where the North Begins and in many films that followed. Duncan would then demonstrate how he worked with the dog, saying that it was best to use a low voice with “a tone of mild entreaty.” He didn’t believe in bribing Rin Tin Tin with food or excessive praise: he rewarded him by letting him play with a squeaky rubber doll he had first given to Rinty when he was a puppy. At this point in the show, Duncan would run Rinty through some of his tricks—his belly-crawling, his ability to stand stock-still for minutes on end, his range of expressions from anger to delight to dread.

One such night, according to a writer named Francis Rule, Duncan began by calling Rinty, and then, for laughs, scolded him after he strolled lazily onstage, stretched, and yawned. “There then followed one of the most interesting exhibitions I have ever witnessed,” Rule wrote, in Picture-Play Magazine. As Duncan led Rinty through a series of acting exercises, “there was between that dog and his master as perfect an understanding as could possibly exist between two living beings.” Duncan “scarcely touched him during the entire proceedings—he stood about eight feet away and simply gave directions. And it fairly took your breath away to watch that dog respond, his ears up unless told to put them down and his eyes intently glued on his master. There was something almost uncanny about it.”

Everywhere Duncan and Rinty appeared, the dog was treated like a dignitary. In New York, Mayor Jimmy Walker gave him a key to the city. In Portland, Oregon, he was welcomed as “a distinguished canine visitor,” and was met at the train station by the city’s school superintendent, the chief of police, and the head of the local Humane Society. Then Rinty made a statesmanlike pilgrimage to the grave of Bobbie the Oregon Wonder Dog. During the ceremony, according to one report, “Rin Tin Tin with his own teeth placed the flowers on Bobbie’s grave and then in a moment’s silence laid his head on the cross marking the resting place of the dog.” The next day, at Portland’s Music Box Theatre, Rinty was presented with the Abraham Lincoln humanitarian award and medal for distinguished service.

In 1924, the studio began work on Find Your Man. The director was Mal St. Clair, and the writer was, in the words of Jack Warner, a “downy-cheeked youngster who looked as though he had just had the bands removed from his teeth so he could go to the high school prom.” The youngster was Darryl Zanuck, the son of a professional gambler; Zanuck had come to Hollywood from Nebraska, when he was seventeen. One of his first jobs was writing ads for Yuccatone Hair Restorer. His slogan, “You’ve Never Seen a Bald-Headed Indian,” helped make Yuccatone a success, until bottles of the hair tonic fermented and exploded in twenty-five drugstores, and the company was driven out of business. Zanuck left advertising to work for the director Mack Sennett and, later, for Charlie Chaplin. Mal St. Clair had also worked with Sennett, and several of his films had included dogs.

The movie that Zanuck had in mind was set in a remote timber camp. He and St. Clair acted it out for Harry Warner, with Zanuck playing the part of the dog. With Warner’s approval, production started almost immediately. Billed as “Wholesome Melodrama At Its Very Best” that starred “Rin Tin Tin the Wonder Dog,” the movie was a “box office rocket,” in Jack Warner’s words.

The next Rin Tin Tin movie, Lighthouse by the Sea, was also written by Zanuck and released in 1924. It concerned a pretty girl and her father, a lighthouse keeper who is going blind. Warner Bros. even held screenings for the blind. There was a narrator onstage who described the action and read the intertitle cards, which included “He’s so tough I have to feed him manhole covers for biscuits!,” “This pup can whip his weight in alligators—believe me!,” and “I thought you said that flea incubator could fight!”

Zanuck always acknowledged that Rin Tin Tin had given him his entree into Warner Bros., but he later told interviewers that he disliked the dog and hated writing for him. Even so, he wrote at least ten more scripts for Rinty, all of them great successes. By the time he was twenty-five, Zanuck was running the studio.

Rinty’s films were so profitable that Warner Bros. paid him two thousand dollars a week; even at that, Rin Tin Tin was a bargain. Around the Warner Bros. lot, he was called “the mortgage lifter,” because every time the studio was in financial straits it released a Rin Tin Tin movie and the income from it set things right again. Duncan was given every privilege: he was driven to the set each day, and he had an office on the Warner Bros. lot, where he sifted through the fan mail and the little mementos that arrived for Rin Tin Tin.

Duncan had never imagined this part of the equation. He started buying snappy clothes and cars. He bought land in Beverly Hills and built a house for himself and his mother. The house is now gone, and it’s hard to know much about it; in his memoir, Duncan talked mostly about the kennel he built for the dogs. Then he bought a house in North Hollywood for his sister, Marjorie. His biggest splurge was on a beach house in a gated section of Malibu, where his neighbors were Hollywood stars.

On top of the movie income, Rinty was signed to endorsement deals. An executive from Chappel Brothers, which had recently introduced Ken-L Ration, the first commercial canned dog food, was so eager to have Rin Tin Tin as a spokesperson that, in a meeting with Duncan, he ate a can of it to demonstrate its tastiness. Duncan was convinced. Rinty was featured in ads for Ken-L Ration, Ken-L-Biskit, and Pup-E-Crumbles brands, with the slogan “My Favorite Food! Most Faithfully, Rin Tin Tin.”

Of the six Rin Tin Tin silent films still available, the most memorable is Clash of the Wolves (1925). Rinty plays a half-dog, half-wolf named Lobo, who is living in the wild as the leader of a wolf pack. The film begins with a vivid and disturbing scene of a forest fire, which drives Lobo and his pack, including Nanette and their pups, from their forest home to the desert ranchlands, where they prey on cattle to survive. The ranchers hate the wolves, especially Lobo; a bounty of a hundred dollars is offered as a reward for his hide. In the meantime, a young mineral prospector named Dave arrives in town. A claim jumper who lusts after Dave’s mineral discovery (and Dave’s girlfriend, Mae) soon schemes against him. Mae happens to be the daughter of the rancher who is most determined to kill Lobo and who also doesn’t like Dave.

The wolves, led by Lobo, attack a steer, and the ranchers set out after them. The chase is fast and frightening, and when Rin Tin Tin weaves through the horses’ churning legs it looks as if he were about to be trampled. He outruns the horses, his body flattened and stretched as he bullets along the desert floor, and, if you didn’t see the little puffs of dust when his paws touch the ground, you’d swear he was floating. He scrambles up a tree—a stunt so startling that it has to be replayed a few times to believe it. Can dogs climb trees? Evidently. At least, certain dogs can. And they can climb down, too, and then tear along a rock ridge, and then come to a halt at the narrow crest of the ridge. The other side of the gorge looks miles away. Rin Tin Tin stops, pivots; you feel him calculating his options; then he crouches and leaps, and the half-second before he lands safely feels long and fraught. His feet touch ground and he scrambles on, but moments later he plummets off the edge of another cliff, slamming through the branches of a cactus, collapsing in a heap, with a cactus needle skewered through the pad of his foot.

The action is thrilling, but the best part of the movie is the quieter section, after Rin Tin Tin falls. He limps home, stopping every few steps to lick his injured paw; his bearing is so abject that it is easy to understand why Duncan felt the need to explain that it was just acting. Rin Tin Tin hobbles into his den and collapses next to Nanette, in terrible pain.

“He was abandoned in the D.C.

area as a puppy and raised

by a pack of senators.”

In an earlier scene in the movie, one of the wolves is injured and the pack musters around him. At first, it looks as if they were coming to his aid, but, suddenly, their actions seem more agitated than soothing, and just then an intertitle card flashes up, saying simply, “The Law of the Pack. Death to the wounded wolf.” So we know that the other wolves will kill Lobo if they realize that he’s injured. Rinty and Nanette try to work on the cactus needle in his paw surreptitiously. But the pack senses that something is wrong. Finally, one of them approaches, a black look on his face, ready to attack. Rinty draws himself up and snarls. The two animals freeze, and then Rinty snarls again, almost sotto voce, as if he were saying, “I don’t care what you think you know about my condition. I am still the leader here.” The murderous wolf backs off.

The rest of the plot is a crosshatch of misperception and treachery. Rinty, fearing that he will still be killed by his pack and attract harm to Nanette and their pups, leaves, so that he might die alone, and his wobbling, wincing departure is masterly acting. Dave comes upon Rinty as he is on his death walk. Knowing there is a bounty for the dog, he pulls out his gun, but then gives in to his sympathy for the suffering animal and removes the cactus thorn. (Charles Farrell, who played Dave, must have been a brave man; Rinty was required to snap and snarl at him in that scene, and there are a few snaps when Rinty looks like he’s not kidding.) Dave’s decision to save Lobo is of great consequence, because, of course, Lobo ends up saving Dave’s life. Lobo chooses to be a dog—a guardian—and protect Dave, rather than give in to his wolf impulse to be a killer.

The film has its share of silliness—a scene in which Rinty wears a beard as a disguise to avoid being identified as Lobo, for example—and, to the modern eye, the human acting is stilted. But Clash of the Wolves shows why so many millions of people fell in love with Rin Tin Tin.

By the middle of the twenties, the movie business had grown into one of the ten biggest industries in the United States. According to the historian Ann Elwood, almost a hundred million movie tickets were sold each week, to a population of a hundred and fifteen million. In 1928, Warner Bros. was worth sixteen million dollars; two years later, it was worth two hundred million. It still had the reputation of being second-rate, compared with Paramount or M-G-M, but it was expanding and innovating. It had launched a chain of movie palaces, with orchestras and elaborate, thematic décor—Arabian nights in one theatre, Egyptian days or Beaux Arts Paris in another—and, best of all, air-conditioning, which was rare in public buildings, and even rarer in private homes.

In 1927, four Rin Tin Tin films were released, and during breaks in the production schedule Duncan and Rinty were on the road doing stage appearances. Duncan hardly had a life at home. Charlotte Anderson had filed for divorce. She said she didn’t like Rinty, and didn’t like competing with him. In the proceedings, she charged that Duncan didn’t love her or her horses: “All he cared for was Rin Tin Tin,” she testified. An article in the Los Angeles Times noted, “Evidently, Rin Tin Tin’s company was so much pleasure to Duncan that he considered Mrs. Duncan’s presence rather secondary.”

Otherwise, the year was a high point for Duncan. The four films—A Dog of the Regiment, Jaws of Steel, Tracked by the Police, and Hills of Kentucky—were box-office hits as well as critical successes. The Academy Awards were presented for the first time two years later, and, according to Hollywood legend, Rinty received the most votes for best actor. But members of the Academy, anxious to establish that the awards were serious and important, decided that giving an Oscar to a dog did not serve that end. (The award went to Emil Jannings.)

Even without the Oscar, Rinty was in the news all the time. He was frequently given an honorific: the King of Pets; the Famous Police Dog of the Movies; the Dog Wonder; the Wonder Dog of the Stage and Screen; the Wonder Dog of All Creation; the Mastermind Dog; the Marvelous Dog of the Movies; and America’s Greatest Movie Dog. In 1928, a review of Rin Tin Tin’s film A Race for Life began with the question “Strongheart who?”

| 2011 |