If I were a bitch, I’d be in love with Biff Truesdale. Biff is perfect. He’s friendly, good-looking, rich, famous, and in excellent physical condition. He almost never drools. He’s not afraid of commitment. He wants children—actually, he already has children and wants a lot more. He works hard and is a consummate professional, but he also knows how to have fun.

What Biff likes most is food and sex. This makes him sound boorish, which he is not—he’s just elemental. Food he likes even better than sex. His favorite things to eat are cookies, mints, and hotel soap, but he will eat just about anything. Richard Krieger, a friend of Biff’s who occasionally drives him to appointments, said not long ago, “When we’re driving on I-95, we’ll usually pull over at McDonald’s. Even if Biff is napping, he always wakes up when we’re getting close. I get him a few plain hamburgers with buns—no ketchup, no mustard, and no pickles. He loves hamburgers. I don’t get him his own French fries, but if I get myself fries I always flip a few for him into the back.”

If you’re ever around Biff while you’re eating something he wants to taste—cold roast beef, a Wheatables cracker, chocolate, pasta, aspirin, whatever—he will stare at you across the pleated bridge of his nose and let his eyes sag and his lips tremble and allow a little bead of drool to percolate at the edge of his mouth until you feel so crummy that you give him some. This routine puts the people who know him in a quandary, because Biff has to watch his weight. Usually, he is as skinny as Kate Moss, but he can put on three pounds in an instant. The holidays can be tough. He takes time off at Christmas and spends it at home, in Attleboro, Massachusetts, where there’s a lot of food around and no pressure and no schedule and it’s easy to eat all day. The extra weight goes to his neck. Luckily, Biff likes working out. He runs for fifteen or twenty minutes twice a day, either outside or on his Jog-Master. When he’s feeling heavy, he runs longer, and skips snacks, until he’s back down to his ideal weight of seventy-five pounds.

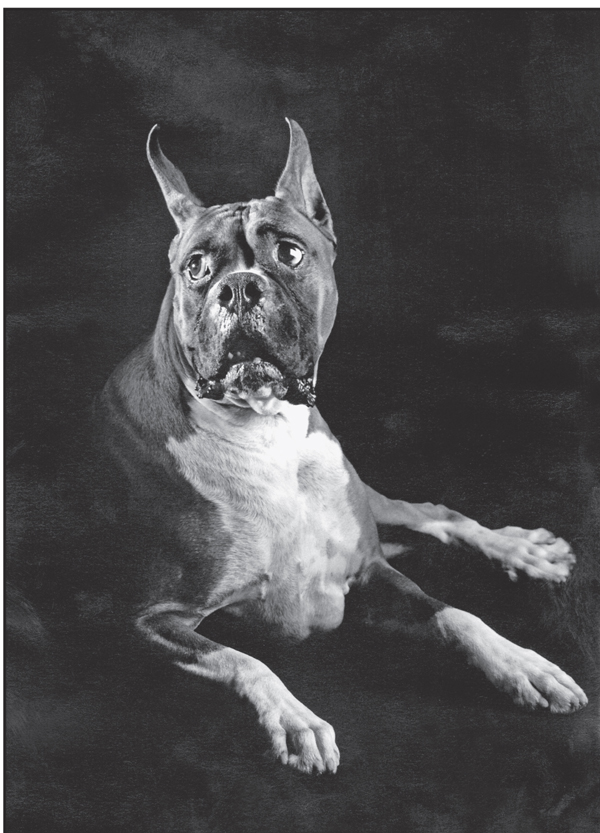

Biff is a boxer. He is a show dog—he performs under the name Champion Hi-Tech’s Arbitrage—and so looking good is not mere vanity; it’s business. A show dog’s career is short, and judges are unforgiving. Each breed is judged by an explicit standard for appearance and temperament, and then there’s the incalculable element of charisma in the ring. When a show dog is fat or lazy or sullen, he doesn’t win; when he doesn’t win, he doesn’t enjoy the ancillary benefits of being a winner, like appearing as the celebrity spokesmodel on packages of Pedigree Mealtime with Lamb and Rice, which Biff will be doing soon, or picking the best-looking bitches and charging them six hundred dollars or so for his sexual favors, which Biff does three or four times a month. Another ancillary benefit of being a winner is that almost every single weekend of the year, as he travels to shows around the country, he gets to hear people applaud for him and yell his name and tell him what a good boy he is, which is something he seems to enjoy at least as much as eating a bar of soap.

Pretty soon, Biff won’t have to be so vigilant about his diet. After he appears at the Westminster Kennel Club’s show, this week, he will retire from active show life and work full time as a stud. It’s a good moment for him to retire. Last year, he won more shows than any other boxer, and also more than any other dog in the purebred category known as Working Dogs, which also includes Akitas, Alaskan malamutes, Bernese mountain dogs, bullmastiffs, Doberman pinschers, giant schnauzers, Great Danes, Great Pyrenees, komondors, kuvaszok, mastiffs, Newfoundlands, Portuguese water dogs, Rottweilers, St. Bernards, Samoyeds, Siberian huskies, and standard schnauzers. Boxers were named for their habit of standing on their hind legs and punching with their front paws when they fight. They were originally bred to be chaperons—to look forbidding while being pleasant to spend time with. Except for show dogs like Biff, most boxers lead a life of relative leisure. Last year at Westminster, Biff was named Best Boxer and Best Working Dog, and he was a serious contender for Best in Show, the highest honor any show dog can hope for. He is a contender to win his breed and group again this year, and is a serious contender once again for Best in Show, although the odds are against him, because this year’s judge is known as a poodle person.

Biff is four years old. He’s in his prime. He could stay on the circuit for a few more years, but by stepping aside now he is making room for his sons Trent and Rex, who are just getting into the business, and he’s leaving while he’s still on top. He’ll also spend less time in airplanes, which is the one part of show life he doesn’t like, and more time with his owners, William and Tina Truesdale, who might be persuaded to waive his snacking rules.

Biff has a short, tight coat of fox-colored fur, white feet and ankles, and a patch of white on his chest roughly the shape of Maine. His muscles are plainly sketched under his skin, but he isn’t bulgy. His face is turned up and pushed in, and has a dark mask, spongy lips, a wishbone-shaped white blaze, and the earnest and slightly careworn expression of a small-town mayor. Someone once told me that he thought Biff looked a little bit like President Clinton. Biff’s face is his fortune. There are plenty of people who like boxers with bigger bones and a stockier body and taller shoulders—boxers who look less like marathon runners and more like weight-lifters—but almost everyone agrees that Biff has a nearly perfect head.

“I can’t sleep.”

“Biff’s head is his father’s,” William Truesdale, a veterinarian, explained to me one day. We were in the Truesdales’ living room in Attleboro, which overlooks acres of hilly fenced-in fields. Their house is a big, sunny ranch with a stylish pastel kitchen and boxerabilia on every wall. The Truesdales don’t have children, but at any given moment they share their quarters with at least a half-dozen dogs. If you watch a lot of dog-food commercials, you may have seen William—he’s the young, handsome, dark-haired veterinarian declaring his enthusiasm for Pedigree Mealtime while his boxers gallop around.

“Biff has a masculine but elegant head,” William went on. “It’s not too wet around the muzzle. It’s just about ideal. Of course, his forte is right here.” He pointed to Biff’s withers, and explained that Biff’s shoulder-humerus articulation was optimally angled, and bracketed his superb brisket and forelegs, or something like that. While William was talking, Biff climbed onto the couch and sat on top of Brian, his companion, who was hiding under a pillow. Brian is an English toy Prince Charles spaniel who is about the size of a teakettle and has the composure of a hummingbird. As a young competitor, he once bit a judge—a mistake Tina Truesdale says he made because at the time he had been going through a little mind problem about being touched. Brian, whose show name is Champion Cragmor’s Hi-Tech Man, will soon go back on the circuit, but now he mostly serves as Biff’s regular escort. When Biff sat on him, he started to quiver. Biff batted at him with his front leg. Brian gave him an adoring look.

“Biff’s body is from his mother,” Tina was saying. “She had a lot of substance.”

“She was even a little extreme for a bitch,” William said. “She was rather buxom. I would call her zaftig.”

“Biff’s father needed that, though,” Tina said. “His name was Tailo, and he was fabulous. Tailo had a very beautiful head, but he was a bit fine, I think. A bit slender.”

“Even a little feminine,” William said, with feeling. “Actually, he would have been a really awesome bitch.”

The first time I met Biff, he sniffed my pants, stood up on his hind legs and stared into my face, and then trotted off to the kitchen, where someone was cooking macaroni. We were in Westbury, Long Island, where Biff lives with Kimberly Pastella, a twenty-nine-year-old professional handler, when he’s working. Last year, Kim and Biff went to at least one show every weekend. If they drove, they took Kim’s van. If they flew, she went coach and he went cargo. They always shared a hotel room.

While Kim was telling me all this, I could hear Biff rummaging around in the kitchen. “Biffers!” Kim called out. Biff jogged back into the room with a phony look of surprise on his face. His tail was ticking back and forth. It is cropped so that it is about the size and shape of a half-smoked stogie. Kim said that there was a bitch downstairs who had been sent from Pennsylvania to be bred to one of Kim’s other clients, and that Biff could smell her and was a little out of sorts. “Let’s go,” she said to him. “Biff, let’s go jog.” We went into the garage, where a treadmill was set up with Biff’s collar suspended from a metal arm. Biff hopped on and held his head out so that Kim could buckle his collar. As soon as she leaned toward the power switch, he started to jog. His nails clicked a light tattoo on the rubber belt.

“First, they do an on-line search.”

Except for a son of his named Biffle, Biff gets along with everybody. Matt Stander, one of the founders of Dog News, said recently, “Biff is just very, very personable. He has a je ne sais quoi that’s really special. He gives of himself all the time.” One afternoon, the Truesdales were telling me about the psychology that went into making Biff who he is. “Boxers are real communicators,” William was saying. “We had to really take that into consideration in his upbringing. He seems tough, but there’s a fragile ego inside there. The profound reaction and hurt when you would raise your voice at him was really something.”

“I made him,” Tina said. “I made Biff who he is. He had an overbearing personality when he was small, but I consider that a prerequisite for a great performer. He had such an attitude! He was like this miniature man!” She shimmied her shoulders back and forth and thrust out her chin. She is a dainty, chic woman with wide-set eyes and the neck of a ballerina. She grew up on a farm in Costa Rica, where dogs were considered just another form of livestock. In 1987, William got her a Rottweiler for a watchdog, and a boxer, because he had always loved boxers, and Tina decided to dabble with them in shows. Now she makes a monogrammed Christmas stocking for each animal in their house, and she watches the tape of Biff winning at Westminster approximately once a week. “Right from the beginning, I made Biff think he was the most fabulous dog in the world,” Tina said.

“He doesn’t take after me very much,” William said. “I’m more of a golden retriever.”

“Oh, he has my nature,” Tina said. “I’m very strong-willed. I’m brassy. And Biff is an egotistical, self-centered, selfish person. He thinks he’s very important and special, and he doesn’t like to share.”

Biff is priceless. If you beg the Truesdales to name a figure, they might say that Biff is worth around a hundred thousand dollars, but they will also point out that a Japanese dog fancier recently handed Tina a blank check for Biff. (She immediately threw it away.) That check notwithstanding, campaigning a show dog is a money-losing proposition for the owner. A good handler gets three or four hundred dollars a day, plus travel expenses, to show a dog, and any dog aiming for the top will have to be on the road at least a hundred days a year. A dog photographer charges hundreds of dollars for a portrait, and a portrait is something that every serious owner commissions, and then runs as a full-page ad in several dog-show magazines. Advertising a show dog is standard procedure if you want your dog or your presence on the show circuit to get well known. There are also such ongoing show-dog expenses as entry fees, hair-care products, food, health care, and toys. Biff’s stud fee is six hundred dollars. Now that he will not be at shows, he can be bred several times a month. Breeding him would have been a good way for him to make money in the past, except that whenever the Truesdales were enthusiastic about a mating they bartered Biff’s service for the pick of the litter. As a result, they now have more Biff puppies than Biff earnings. “We’re doing this for posterity,” Tina says. “We’re doing it for the good of all boxers. You simply can’t think about the cost.”

On a recent Sunday, I went to watch Biff work at one of the last shows he would attend before his retirement. The show was sponsored by the Lehigh Valley Kennel Club and was held in a big, windy field house on the campus of Lehigh University, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The parking lot was filled with motor homes pasted with life-size decals of dogs. On my way to the field house, I passed someone walking an Afghan hound wearing a snood, and someone else wiping down a Saluki with a Flintstones beach towel. Biff was napping in his crate—a fancy-looking brass box with bright silver hardware and with luggage tags from Delta, USAir, and Continental hanging on the door. Dogs in crates can look woeful, but Biff actually likes spending time in his. When he was growing up, the Truesdales decided they would never reprimand him, because of his delicate ego. Whenever he got rambunctious, Tina wouldn’t scold him—she would just invite him to sit in his crate and have a time-out.

On this particular day, Biff was in the crate with a bowl of water and a gourmet Oinkeroll. The boxer judging was already over. There had been thirty-three in competition, and Biff had won Best in Breed. Now he had to wait for several hours while the rest of the working breeds had their competitions. Later, the breed winners would square off for Best in Working Group. Then, around dinnertime, the winner of the Working Group and the winners of the other groups—sporting dogs, hounds, terriers, toys, non-sporting dogs, and herding dogs—would compete for Best in Show. Biff was stretched out in the crate with his head resting on his forelegs, so that his lips draped over his ankle like a café curtain. He looked bored. Next to his crate, several wire-haired fox terriers were standing on tables getting their faces shampooed, and beyond them a Chihuahua in a pink crate was gnawing on its door latch. Two men in white shirts and dark pants walked by eating hot dogs. One of them was gesturing and exclaiming, “I thought I had good dachshunds! I thought I had great dachshunds!”

Biff sighed and closed his eyes.

While he was napping, I pawed through his suitcase. In it was some dog food; towels; an electric nail grinder; a whisker trimmer; a wool jacket in a lively pattern that looked sort of Southwestern; an apron; some antibiotics; baby oil; coconut-oil coat polish; boxer chalk powder; a copy of Dog News; an issue of ShowSight magazine, featuring an article subtitled “Frozen Semen—Boon or Bane?” and a two-page ad for Biff, with a full-page, full-color photograph of him and Kim posed in front of a human-size toy soldier; a spray bottle of fur cleanser; another Oinkeroll; a rope ball; and something called a Booda Bone. The apron was for Kim. The baby oil was to make Biff’s nose and feet glossy when he went into the ring. Boxer chalk powder—as distinct from, say, West Highland–white-terrier chalk powder—is formulated to cling to short, sleek boxer hair and whiten boxers’ white markings. Unlike some of the other dogs, Biff did not need to travel with a blow dryer, curlers, nail polish, or detangling combs, but, unlike some less sought-after dogs, he did need a schedule. He was registered for a show in Chicago the next day, and had an appointment at a clinic in Connecticut the next week to make a semen deposit, which had been ordered by a breeder in Australia. Also, he had a date that same week with a bitch named Diana who was about to go into heat. Biff has to book his stud work after shows, so that it doesn’t interfere with his performance. Tina Truesdale told me that this was typical of all athletes, but everyone who knows Biff is quick to comment on how professional he is as a stud. Richard Krieger, who was going to be driving Biff to his appointment at the clinic in Connecticut, once told me that some studs want to goof around and take forever but Biff is very businesslike. “Bing, bang, boom,” Krieger said. “He’s in, he’s out.”

“No wasting of time,” said Nancy Krieger, Richard’s wife. “Bing, bang, boom. He gets the job done.”

After a while, Kim showed up and asked Biff if he needed to go outside. Then a handler who is a friend of Kim’s came by. He was wearing a black-and-white houndstooth suit and was brandishing a comb and a can of hair spray. While they were talking, I leafed through the show catalogue and read some of the dogs’ names to Biff, just for fun—names like Aleph Godol’s Umbra Von Carousel and Champion Spanktown Little Lu Lu and Ranchlake’s Energizer O’Motown and Champion Beaverbrook Buster V Broadhead. Biff decided that he did want to go out, so Kim opened the crate. He stepped out and stretched and yawned like a cat, and then he suddenly stood up and punched me in the chest. An announcement calling for all toys to report to their ring came over the loudspeaker. Kim’s friend waved the can of hair spray in the direction of a little white poodle shivering on a table a few yards away and exclaimed, “Oh, no! I lost track of time! I have to go! I have to spray up my miniature!”

Typically, dog contestants first circle the ring together; then each contestant poses individually for the judge, trying to look perfect as the judge lifts its lips for a dental exam, rocks its hindquarters, and strokes its back and thighs. The judge at Lehigh was a chesty, mustached man with watery eyes and a grave expression. He directed the group with hand signals that made him appear to be roping cattle. The Rottweiler looked good, and so did the giant schnauzer. I started to worry. Biff had a distracted look on his face, as if he’d forgotten something back at the house. Finally, it was his turn. He pranced to the center of the ring. The judge stroked him and then waved his hand in a circle and stepped out of the way. Several people near me began clapping. A flashbulb flared. Biff held his position for a moment, and then he and Kim bounded across the ring, his feet moving so fast that they blurred into an oily sparkle, even though he really didn’t have very far to go. He got a cookie when he finished the performance, and another a few minutes later, when the judge wagged his finger at him, indicating that Biff had won again.

You can’t help wondering whether Biff will experience the depressing letdown that retired competitors face. At least, he has a lot of stud work to look forward to, although William Truesdale complained to me once that the Truesdales’ standards for a mate are so high—they require a clean bill of health and a substantial pedigree—that “there just aren’t that many right bitches out there.” Nonetheless, he and Tina are optimistic that Biff will find enough suitable mates to become one of the most influential boxer sires of all time. “We’d like to be remembered as the boxer people of the nineties,” Tina said. “Anyway, we can’t wait to have him home.”

“We’re starting to campaign Biff’s son Rex,” William said. “He’s been living in Mexico, and he’s a Mexican champion, and now he’s ready to take on the American shows. He’s very promising. He has a fabulous rear.”

Just then, Biff, who had been on the couch, jumped down and began pacing. “Going somewhere, honey?” Tina asked.

He wanted to go out, so Tina opened the back door, and Biff ran into the back yard. After a few minutes, he noticed a ball on the lawn. The ball was slippery and a little too big to fit in his mouth, but he kept scrambling and trying to grab it. In the meantime, the Truesdales and I sat, stayed for a moment, fetched ourselves turkey sandwiches, and then curled up on the couch. Half an hour passed, and Biff was still happily pursuing the ball. He probably has a very short memory, but he acted as if it were the most fun he’d ever had.

| 1995 |

RICHARD COHEN

In the past, the only recourse for a dog who craved fame was Hollywood. A dog was either a movie dog or a house pet, end of discussion. While a few dogs became celebrities, the vast majority passed through life unknown, leaving behind no more than a handful of memories scattered like bones across back yards and living rooms. Then, in 1990, Chuck Svoboda and Frank Simon, two men working the Southwest border for the United States Customs Service, decided that something had to be done to get some less flashy dogs a little more attention. They discussed the problem with their immediate supervisor, and, as a result, the United States Customs Service issued nine baseball-style trading cards, each picturing a drug-detecting dog and listing the dog’s age, breed, seizure record, and most notable achievement. The cards, which are distributed to schoolchildren, show canine agents sniffing tires, standing in pickups, and straining in the glare of the midday Texas sun. Real dogs solving real problems.

We learned all this from Morris Berkowitz, who is a canine-program manager with the Customs Service and is determined to improve the image of the working dog. “These dogs may not play ball,” he likes to say, “but they can do a little trick called ‘stop crime.’ ”

Last April, Milk-Bone Dog Biscuits, part of a division of Nabisco Foods, took the dog-card concept a step further: it named two dozen canine agents to an honorary All-Star team, issued a second set of cards, celebrating these dogs, and began putting them inside boxes of Milk-Bones. A dog handler named August King, who is partnered with a sixty-pound yellow Labrador retriever, claims that the cards could actually work as deterrents to drug trafficking. “When dealers get a look at the dogs stacked against them, they just might change their plans,” he told us. Nabisco executives speak in more general terms. “The cards put us on the side of the good dog and good dogs everywhere,” a company spokesman said.

All told, three hundred and forty-seven dogs are employed by the Customs Service, and police America’s airports, seaports, and border checkpoints. It was twenty-four of those dogs that were chosen as All-Stars. Two New York dogs made the squad. “Rufus and Jack—both are legends, but Rufus is an animal I truly respect,” Mr. Berkowitz said. Last year, while searching a cargo truck, Rufus, a sad-eyed springer spaniel, uncovered nine hundred pounds of cocaine, and in the course of his career he has found over eighty million dollars’ worth of narcotics. “To understand how remarkable that stat is, you should know that Rufus is at least thirteen years old and that most dogs retire at around nine,” Mr. Berkowitz explained. “It’s not that they lose their desire; their bodies just won’t do what they once did. The retired dogs spend their days like civilian dogs—lying in front of a TV or running around some yard. But Rufus is unstoppable. He’s like Nolan Ryan.”

In their pictures, the dogs look stern and businesslike—all but Corky. Corky, a member of the All-Stars, is a beige cocker spaniel with floppy ears and thick fur, who looks more like a lapdog than like a customs agent. We asked Mr. Berkowitz why a non-active agent (Corky’s card reads “Retired”) was named to the All-Star team—wasn’t that sort of like sending Bill Bradley to the Olympics? “Corky is not an average agent,” Mr. Berkowitz replied. “Corky broke a line many people thought unbreakable. He was the first cute dog to work in Customs. Before Corky, all drug-detection canines were big breeds. Labs or shepherds. But some travellers get spooked by big dogs, so we brought Corky on to sniff. He’s passive. If he picks up a scent, he doesn’t scratch or claw, he simply sits at the suspect’s feet. Before Corky, our people thought drug dogs had to look a certain way. Big and tough. We don’t think that anymore.”

In the light of Corky’s historical role, many drug-dog fans consider his card the set’s most valuable. “All the cards are going to be worth something,” Ann Smith, a public-relations manager for Nabisco, told us. “But if you’re going to hang on to just one, hang on to Corky.” She added that Corky has appeared on the TV show Top Cops, reenacting some of his most dramatic cases, among them the discovery of 56.4 pounds of cocaine in an overnight-courier bag at Miami International Airport. “When I was a kid, I collected baseball cards,” she said. “My favorite card was Johnny Bench crouched behind home plate. If you want to get my Corky, in addition to Bench you have to give me a Ted Williams and a Babe Ruth.”

| 1992 |

Roger Angell

(An opera in four acts, conceived prior to successive evenings at the Westminster Kennel Club Show and the Metropolitan Opera)

CAST

GUGLIELMO—A dashing fox terrier (tenor)

MIMI (Ch. Anthracite Sweet-Stuff of Armonk)—A poodle (soprano)

DON CANINO (her father)—Another poodle (baritone)

BRUTTO—Companion poodle to Don Canino and suitor for the hand of Mimi (basso)

FIDOLETTA—A Lhasa Apso. Nurse to Mimi but secretly enamored of Guglielmo. A real bitch (mezzo)

SPIQUE—A comical bulldog (basso bundo)

DR. FAUSTUS—A veterinary (tenor)

CHORUS: Non-sporting, herding, and terrier contestants; judges, handlers, reporters

(There will be three walks around the block)

After the disastrous failure of his misbegotten early Arfeo at La Scala in the winter of 1843, few expected that Verdi would soon return to the themes of canine anti-clericalism and the proliferation of Labradors (labbrazazione), but his discovery of the traditional Sicilian grooming cavatina—as recapitulated in the touching barkarole “Dov’é il mio guinzaglio?” (“I have lost my leash”) that closes Act III—appears to have sent him back to work. Verdi’s implacable opposition to the Venetian muzzling ordinance of 1850 is to be heard in the rousing “Again a full moon” chorus that resonates so insistently during Brutto’s musings before and after the cabaletta:

At the opening curtain, Guglielmo and Mimi, in adjoining benching stalls, plan their elopement despite the opposition of Don Canino, who has arranged her forthcoming marriage to Brutto despite rumors about the larger male’s parentage. After the lovers’ tender duet “A cuccia, a cuccia, amore mio” (“Sit! Sit, my love!”), recalling their first meeting at an obedience class, they part reluctantly, with Guglielmo distressed at her anxiety over the nuptials: “Che gelida manina” (“Your icy paw”). Don Canino, enlisting the support of the perfidious Fidoletta, plots to dispatch Guglielmo into the K-9 Corps, and, joined by Brutto, the trio, in “Sotto il nostro albero” (“Under the family tree”), jovially celebrates the value of pedigree.

As the judging begins, Guglielmo, alerted to Don Canino’s plot by the faithful Spique, disguises himself as a miniature apricot poodle, but the lovers fail to detect the lurking presence of Don Canino, who has hidden himself among a large entry of Rottweilers in Ring 6. A pitched battle between hostile bands of Lakeland and Bedlington terriers requires the attention of Spique, and in his absence Fidoletta entraps the innocent Guglielmo, who discloses his identity to her. She breaks off their amusing impromptu duet “Non so chi sei” (“I don’t know who you are, but I sure like your gait”) to fetch the police, but Guglielmo makes good his escape through the loges during the taping of a Kal Kan commercial—an octet severely criticized in its day, but to which Mascagni makes clear obeisance in his later sestina, “Mangia, Pucci.”

Guglielmo, not realizing in the darkness that he has found his way back to his natal kennel in Chappaqua, delivers the dirgelike “Osso Bucco” while digging in the yard, but is elated by news from Spique that he has uncovered certain documents in the back-door garbage compactor. Fidoletta, puzzled, trails the valiant pair as they hasten back to the Garden.

In our turbulent final act, the wedding of Mimi and Brutto is interrupted by the arrival of Dr. Faustus, bearing the purloined A.K.C. documents unearthed by Spique. The good vet declares that the nuptials must halt, because Brutto is in fact not only Mimi’s father but (through a separate whelping) her uncle as well. Don Canino, horrified at his own depravity, vows to enter holy orders, and, in a confession, reveals that Brutto is no purebred—“Mira l’occhio azzurro” (“Ol’ Blue Eyes”)—thanks to a Pomeranian on his dam’s side. Dr. Faustus removes Brutto to his laboratory for neutering. Guglielmo, still in disguise, unexpectedly wins a Best of Opposite Sex award in his breed as the lovers are at last united. Guglielmo serenades his Mimi with the “Sono maschio” (“I am a young intact male”) as the happy couple, renouncing show biz, envision their future as a breeding pair with a cut-rate puppy mill in the Garden State Mall. Spique, exhausted by so much unlikelihood, falls asleep on the emptied stage, where his sonorous snores (“Zzzzz”) are joined by those of the audience.

| 1994 |

IAN FRAZIER

Cell phones smell. You wouldn’t think so, but they do. The K-9 Unit of the New Jersey Department of Corrections, while training seven recently acquired cell-phone-sniffing dogs, first put a whole bunch of cell-phone parts in a plastic box to create a kind of sachet of cell-phone scent for use in imprinting. The basic, pervasive cell-phone smell that built up in the closed box was powerful—a sweetish, metallic, ozoney, weird robotic reek. People would never carry such a rank object as a cell phone in their pockets if their noses were as good as a dog’s.

To Troy, Ernie, Chance, and the other muscular, well-fed, and extremely enthusiastic dogs who search for illegal cell phones inside New Jersey’s thirteen state prisons, the smell of a cell phone is bliss. They love to follow it, love finding its source even more. While held in restraint, just before the search, they emit low, well-disciplined whines of almost unbearable expectation. And when they do find the cell phone—or the cell-phone charger, the earpiece, the battery, or any other related object that somehow picked up cell-phone scent (recently a cell-phone-sniffing dog, though not trained to search for narcotics, found some narcotics that had evidently been stored next to a cell phone)—the dogs react with a panting, whining, scratching happiness greater than any human happiness by a factor similar to that by which a dog’s sense of smell is said to be better than ours.

Inside a prison, cell phones defeat some of the purpose of incarceration. They’re among the biggest problems prison officials face. Criminals with cell phones continue to run their gangs even while locked up. How do they get the phones? “Oh, gee—all kinds of ways,” Thomas Moran, the New Jersey D.O.C. chief of staff, said the other day. “Their friends shoot ’em over the fence with potato guns, fly ’em in on model airplanes, arrows … Body cavities, of course, when a girlfriend visits. Packages. Food deliveries. F.C.C. regulations say we can’t interfere with cell-phone transmissions by jamming. Going after the illegal phones with dogs is by far the most efficient means.”

Recently, the officers of the K-9 Unit held a demonstration with their cell-phone dogs on the grounds of the Albert C. Wagner Youth Correctional Facility, in central Jersey farm country. The officers are so proud of their dogs they beam. As the dogs found cell phones hidden in lockers and near bunks in an unused dorm building, and sniffed out a dog-tooth-marked cell phone in the weeds of a field, the officers explained the program.

Captain Matthew Kyle: “We don’t want to publicate what the cell-phone smell is exactly. It’s an organic substance that’s in all cell phones—leave it at that. The dogs can smell it even when it’s masked. They can find it if the cell phone’s in water, oil, peanut butter—anywhere.”

Sergeant William Crampton: “Only time we ever had a dog indicate inaccurately was on a diabetic test kit one individual had.”

Officer Donald Mitchell: “We worked with thirteen dogs to get the seven we have now. Some dogs we had to fail out for environmental reasons. The dog can’t work in the prison environment. Maybe a dog don’t like the slippery floors in the cellblock, or the noise, or the food odors. Some dogs don’t like heights. On the top tier of cells you’re looking down through a floor grating four or five stories. There’s dogs won’t walk on that. Or they don’t like the heat up there in the summer.”

Officer Joseph Nicholas: “All our dogs right now are German shepherds or Labs. We did try one golden retriever, but we had to fail him out. That dog was too easygoing. He’d come in a room on a search and just lay down. We sent him back to the Seeing Eye dog center in Morristown, where all our cell-phone dogs came from. That golden was a lover, not a fighter.”

Captain Kyle: “Very few other states have cell-phone-dog programs like ours—Maryland and Virginia are two of them. There’s a private contractor in California that trains dogs for cell-phone work, but they charge twenty-one thousand dollars for three dogs. We trained all our dogs ourselves, saving the taxpayers money. Since we started with our first three dogs, in October of 2008, we’ve found a hundred and thirty-three cell phones, a hundred and twenty-eight chargers, and I am not sure how many earpieces, batteries, and other items. We believe that eventually every prison system in the country will be using cell-phone dogs.”

| 2009 |