It was the season of mud, drainpipes drooling, the gutters clogged with debris, a battered and penitential robin fixed like a statue on every lawn. Julian was up early, a Saturday morning, beating eggs with a whisk and gazing idly out the kitchen window and into the colorless hide of the day, expecting nothing, when all at once the scrim of rain parted to reveal a dark, crouching presence in the far corner of the yard. At first glance, he took it to be a dog—a town ordinance that he particularly detested disallowed fences higher than three feet, and so the contiguous lawns and flower beds of the neighborhood had become a sort of open savanna for roaming packs of dogs—but before the wind shifted and the needling rain closed in again he saw that he was wrong. This figure, partially obscured by the resurgent forsythia bush, seemed out of proportion, all limbs, as if a dog had been mated with a monkey. What was it, then? Raccoons had been at the trash lately, and he’d seen an opossum wavering down the street like a pale ghost one night after a dreary, overwrought movie Cara had insisted upon, but this was no opossum. Or raccoon, either. It was dark in color, whatever it was—a bear, maybe, a yearling strayed down from the high ridges along the river, and hadn’t Ben Ober told him somebody on F Street had found a bear in their swimming pool? He put down the whisk and went to fetch his glasses.

A sudden eruption of thunder set the dishes rattling on the drainboard, followed by an uncertain flicker of light that illuminated the dark room as if the bulb in the overhead fixture had gone loose in the socket. He wondered how Cara could sleep through all this, but the wonder was short-lived, because he really didn’t give a damn one way or the other if she slept all day, all night, all week. Better she should sleep and give him some peace. He was in the living room now, the gloom ladled over everything, shadows leeching into black holes behind the leather couch and matching armchairs, and the rubber plant a dark ladder in the corner. The thunder rolled again, the lightning flashed. His glasses were atop the TV, where he’d left them the night before while watching a sorry documentary about the children purportedly raised by wolves in India back in the 1920s, two stringy girls in sepia photographs that revealed little and could have been faked, in any case. He put his glasses on and padded back into the kitchen in his stocking feet, already having forgotten why he’d gone to get the glasses in the first place. Then he saw the whisk in a puddle of beaten egg on the counter, remembered, and peered out the window again.

The sight of the three dogs there—a pair of clownish chows and what looked to be a shepherd mix—did nothing but irritate him. He recognized this trio; they were the advance guard of the army of dogs that dropped their excrement all over the lawn, dug up his flower beds, and, when he tried to shoo them, looked right through him as if he didn’t exist. It wasn’t that he had anything against dogs, per se—it was their destructiveness he objected to, their arrogance, as if they owned the whole world and it was their privilege to do as they liked with it. He was about to step to the back door and chase them off, when the figure he’d first seen—the shadow beneath the forsythia bush—emerged. It was no animal, he realized with a shock, but a woman, a young woman dressed all in black, with her black hair hanging wet in her face and the clothes stuck to her like a second skin, down on all fours like a dog herself, sniffing. He was dumbfounded. As stunned and amazed as if someone had just stepped into the kitchen and slapped him till his head rolled back on his shoulders.

He’d been aware of the rumors—there was a new couple in the neighborhood, over on F Street, and the woman was a little strange, dashing through people’s yards at any hour of the day or night, baying at the moon, and showing her teeth to anyone who got in her way—but he’d dismissed them as some sort of suburban legend. Now here she was, in his yard, violating his privacy, in the company of a pack of dogs he’d like to see shot—and their owners, too. He didn’t know what to do. He was frozen in his own kitchen, the omelette pan sending up a metallic stink of incineration. And then the three dogs lifted their heads as if they’d heard something in the distance, the thunder boomed overhead, and suddenly they leaped the fence in tandem and were gone. The woman rose up out of the mud at this point—she was wearing a sodden turtleneck, jeans, a watch cap—locked eyes with him across the expanse of the rain-screened yard for just an instant, or maybe he was imagining this part of it, and then she turned and took the fence in a single bound, vanishing into the rain.

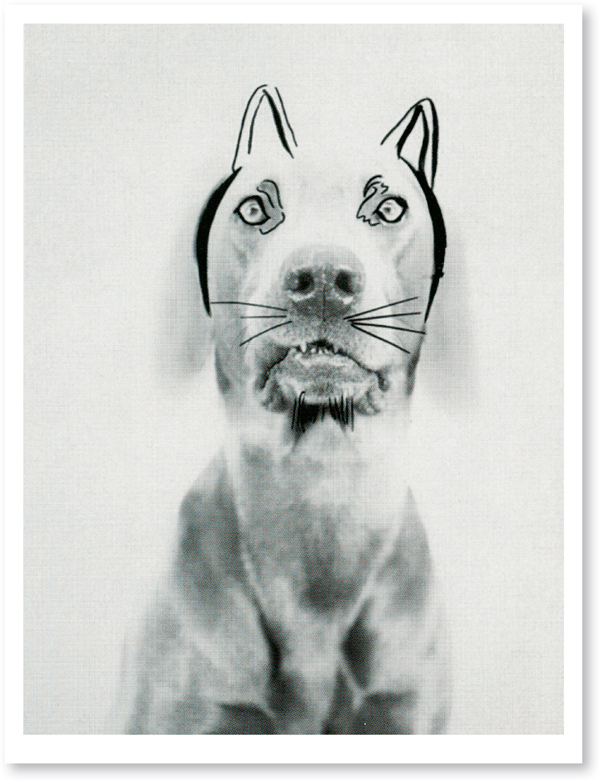

Whatever it was they’d heard, it wasn’t available to her, though she’d been trying to train her hearing away from the ceaseless clatter of the mechanical and tune it to the finer things, the wind stirring in the grass, the alarm call of a fallen nestling, the faintest sliver of a whimper from the dog three houses over, begging to be let out. And her nose. She’d made a point of sticking it in anything the dogs did, breathing deeply, rebooting the olfactory receptors of a brain that had been deadened by perfume and underarm deodorant and all the other stifling odors of civilization. Every smell was a discovery, and every dog discovered more of the world in ten minutes running loose than a human being would discover in ten years of sitting behind the wheel of a car or standing at the lunch counter in a deli or even hiking the Alps. What she was doing, or attempting to do, was nothing short of reordering her senses so that she could think like a dog and interpret the whole world—not just the human world—as dogs did.

Why? Because no one had ever done it before. Whole hordes wanted to be primatologists or climb into speedboats and study whales and dolphins or cruise the veldt in a Land Rover to watch the lions suckle their young beneath the baobabs, but none of them gave a second thought to dogs. Dogs were beneath them. Dogs were common, pedestrian, no more exotic than the housefly or the Norway rat. Well, she was going to change all that. Or at least that was what she’d told herself after the graduate committee rejected her thesis, but that was a long time ago now, two years and more—and the door was rapidly closing.

But here she was, moving again, and movement was good, it was her essence: up over the fence and into the next yard, dodging a clothesline, a cooking grill, a plastic rake, a sandbox, reminding herself always to keep her head down and go quadrupedal whenever possible, because how else was she going to hear, smell, and see as the dogs did? Another fence, and there, at the far end of the yard, a shed, and the dense rust-colored tails of the chows wagging. The rain spat in her face, relentless. It had been coming down steadily most of the night, and now it seemed even heavier, as if it meant to drive her back indoors where she belonged. She was shivering—had been shivering for the past hour, shivering so hard she thought her teeth were coming loose—and as she ran, doubled over in a crouch, she pumped her knees and flapped her arms in an attempt to generate some heat.

What were the dogs onto now? She saw the one she called Barely disappear behind the shed and snake back out again, her tail rigid, sniffing now, barking, and suddenly they were all barking—the two chows and the semi-shepherd she’d named Factitious because he was such a sham, pretending he was a rover when he never strayed more than five blocks from his house, on E Street. There was a smell of freshly turned earth, of compost and wood ash, of the half-drowned worms that Snout the Afghan loved to gobble up off the pavement. She glanced toward the locked gray vault of the house, concerned that the noise would alert whoever lived there, but it was early yet, no lights on, no sign of activity. The dogs’ bodies moiled. The barking went up a notch. She ran, hunched at the waist, hurrying.

And then, out of the corner of her eye, she caught a glimpse of A1, the big-shouldered husky who’d earned his name by consuming half a bottle of steak sauce beside an overturned trash can one bright January morning. He was running—but where had he come from? She hadn’t seen him all night and assumed he’d been wandering out at the limits of his range, over in Bethel or Georgetown. She watched him streak across the yard, ears pinned back, head low, his path converging with hers until he disappeared behind the shed. Angling round the back of the thing—it was aluminum, one of those prefab articles they sell in the big warehouse stores—she found the compost pile her nose had alerted her to (good, good: she was improving) and a tower of old wicker chairs stacked up six feet high. A1 never hesitated. He surged in at the base of the tower, his jaws snapping, and the second chow, the one she called Decidedly, was right behind him—and then she saw: there was something there, a face with incendiary eyes, and it was growling for its life in a thin continuous whine that might have been the drone of a model airplane buzzing overhead.

What was it? She crouched low, came in close. A straggler appeared suddenly, a fluid sifting from the blind side of the back fence to the yard—it was Snout, gangly, goofy, the fastest dog in the neighborhood and the widest ranger, A1’s wife and the mother of his dispersed pups. And then all five dogs went in for the kill.

The thunder rolled again, concentrating the moment, and she got her first clear look: cream-colored fur, naked pink toes, a flash of teeth and burdened gums. It was an opossum, unlucky, doomed, caught out while creeping back to its nest on soft marsupial feet after a night of foraging among the trash cans. There was a roil of dogs, no barking now, just the persistent unravelling growls that were like curses, and the first splintering crunch of bone. The tower of wicker came down with a clatter, chairs upended and scattered, and the dogs hardly noticed. She glanced around her in alarm, but there was nobody to be seen, nothing moving but the million silver drill bits of the rain boring into the ground. Just as the next flash of lightning lit the sky, A1 backed out from under the rumble of chairs with the carcass clenched in his jaws, furiously shaking it to snap a neck that was already two or three times broken, and she was startled to see how big the thing was—twenty pounds of meat, gristle, bone, and hair, twenty pounds at least. He shook it again, then dropped it at his wife’s feet as an offering. It lay still, the other dogs extending their snouts to sniff at it dispassionately, scientists themselves, studying and measuring, remembering. And, when the hairless pink young emerged from the pouch, she tried not to feel anything as the dogs snapped them up one by one.

“You mean you didn’t confront her?” Cara was in her royal-purple robe—her “wrapper,” as she insisted on calling it, as if they were at a country manor in the Cotswolds entertaining Lord and Lady Muckbright instead of in a tract house in suburban Connecticut—and she’d paused with a forkful of mushroom omelette halfway to her mouth. She was on her third cup of coffee and wearing her combative look.

“Confront her? I barely had time to recognize she was human.” He was at the sink, scrubbing the omelette pan, and he paused to look bitterly out into the gray vacancy of the yard. “What did you expect me to do, chase her down? Make a citizen’s arrest? What?”

The sound of Cara buttering her toast—she might have been flaying the flesh from a bone—set his teeth on edge. “I don’t know,” she said, “but we can’t just have strangers lurking around anytime they feel like it, can we? I mean, there are laws—”

“The way you talk you’d think I invited her. You think I like mental cases peeping in the window so I can’t even have a moment’s peace in my own house?”

“So do something.”

“What? You tell me.”

“Call the police, why don’t you? That should be obvious, shouldn’t it? And that’s another thing—”

That was when the telephone rang. It was Ben Ober, his voice scraping through the wires like a set of hard chitinous claws scrabbling against the side of the house. “Julian?” he shouted. “Julian?”

Julian reassured him. “Yeah,” he said, “it’s me. I’m here.”

“Can you hear me?”

“I can hear you.”

“Listen, she’s out in my yard right now, out behind the shed with a, I don’t know, some kind of wolf, it looks like, and that Afghan nobody seems to know who’s the owner of—”

“Who?” he said, but even as he said it he knew. “Who’re you talking about?”

“The dog woman.” There was a pause, and Julian could hear him breathing into the mouthpiece as if he were deep underwater. “She seems to be—I think she’s killing something out there.”

It was high summer, just before the rains set in, and the bush had shrivelled back under the sun till you could see up the skirts of the sal trees, and all that had been hidden was revealed. People began to talk of a disturbing presence in the jungle outside the tiny village of Godamuri in Mayurbhanj district, of a bhut, or spirit, sent to punish them for their refusal to honor the authority of the maharaja. This thing had twice been seen in the company of a wolf, a vague pale slash of movement in the incrassating twilight, but it was no wolf itself, of that that eyewitnesses were certain. Then came the rumor that there were two of them, quick, nasty, bloodless things of the night, and that their eyes flamed with an infernal heat that incinerated anyone who looked into them, and panic gripped the countryside. Mothers kept their children close, fires burned in the night. Then, finally, came the news that these things were concrete and actual and no mere figments of the imagination: their den had been found in an abandoned termitarium in the dense jungle seven miles southeast of the village.

The rumors reached the Reverend J. A. L. Singh, of the Anglican mission and orphanage at Midnapore, and in September, after the monsoon clouds had peeled back from the skies and the rivers had receded, he made the long journey to Godamuri by bullock cart. One of his converts, a Kora tribesman by the name of Chunarem, who was prominent in the area, led him to the site. There, the Reverend, an astute and observant man and an amateur hunter acquainted with the habits of beasts, saw evidence of canine occupation of the termite mound—droppings, bones, tunnels of ingress and egress—and instructed that a machan be built in an overspreading tree. Armed with his dependable 20-bore Westley Richards rifle, the Reverend sat breathlessly in the machan and concentrated his field glasses on the main entrance to the den. The Reverend Singh was not one to believe in ghosts, other than the Holy Spirit, perhaps, and he expected nothing more remarkable than an albino wolf or perhaps a sloth bear gone white with age or dietary deficiency.

Dusk filtered up from the forest floor. Shadows pooled in the undergrowth, and then an early moon rose up pregnant from the horizon to soften them. Langurs whooped in the near distance, cicadas buzzed, a hundred species of beetles, moths, and biting insects flapped round the Reverend’s ears, but he held rigid and silent, his binoculars fixed on the entrance to the mound. And then suddenly a shape emerged, the triangular head of a wolf, then a smaller canine head, and then something else altogether, with a neatly rounded cranium and foreshortened face. The wolf—the dam—stretched herself and slunk off into the undergrowth, followed by a pair of wolf cubs and two other creatures, which were too long-legged and rangy to be canids; that was clear at a glance. Monkeys, the Reverend thought at first, or apes of some sort. But then, even though they were moving swiftly on all fours, the Reverend could see, to his amazement, that these weren’t monkeys at all, or wolves or ghosts, either.

She no longer bothered with a notepad or the pocket tape recorder she’d once used to document the telling yip or strident howl. These were the accoutrements of civilization, and civilization got in the way of the kind of freedom she required if she was ever going to break loose of the constraints that had shackled field biologists from the beginning. Even her clothes seemed to get in the way, but she was sensible enough of the laws of the community to understand that they were necessary, at least for now. Still, she made a point of wearing the same things continuously for weeks on end—sans underwear or socks—in the expectation that her scent would invest them, and the scent of the pack, too. How could she hope to gain their confidence if she smelled like the prize inside a box of detergent?

One afternoon toward the end of March, as she lay stretched out beneath a weak pale disk of a sun, trying to ignore the cold breeze and concentrate on the doings of the pack—they were excavating a den in the vacant quadrangle of former dairy pasture that was soon to become the J and K blocks of the ever-expanding developments—she heard a car slow on the street a hundred yards distant and lifted her head lazily, as the dogs did, to investigate. It had been a quiet morning and a quieter afternoon, with Al and Snout, as the alpha couple, looking on placidly as Decidedly, Barely, and Factitious alternated the digging and a bulldog from B Street she hadn’t yet named lay drooling in the dark wet earth that flew from the lip of the burrow. Snout had been chasing cars off and on all morning—to the dogs, automobiles were animate and ungovernable, big unruly ungulates that needed to be curtailed—and she guessed that the fortyish man climbing out of the sedan and working his tentative way across the lot had come to complain, because that was all her neighbors ever did: complain.

And that was a shame. She really didn’t feel like getting into all that right now—explaining herself, defending the dogs, justifying, forever justifying—because for once she’d got into the rhythm of dogdom, found her way to that sacred place where to lie flat in the sun and breathe in the scents of fresh earth, dung, sprouting grass was enough of an accomplishment for a day. Children were in school, adults at work. Peace reigned over the neighborhood. For the dogs—and for her, too—this was bliss. Hominids had to keep busy, make a buck, put two sticks together, order and structure and complain, but canids could know contentment, and so could she, if she could only penetrate deep enough.

Two shoes had arrived now. Loafers, buffed to brilliance and decorated with matching tassels of stripped hide. They’d come to rest on a trampled mound of fresh earth no more than twenty-four inches from her nose. She tried to ignore them, but there was a bright smear of mud or excrement gleaming on the toe of the left one; it was excrement, dog—the merest sniff told her that, and she was intrigued despite herself, though she refused to lift her eyes. And then a man’s voice was speaking from somewhere high above the shoes, so high up and resonant with authority it might have been the voice of the alpha dog of all alpha dogs—God himself.

The tone of the voice, but not the sense of it, appealed to the dogs, and the bulldog, who was present and accounted for because Snout was in heat, hence the den, ambled over to gaze up at the trousered legs in lovesick awe. “You know,” the voice was saying, “you’ve really got the neighborhood in an uproar, and I’m sure you have your reasons, and I know these dogs aren’t yours—” The voice faltered. “But Ben Ober—you know Ben Ober? Over on C Street? Well, he’s claiming you’re killing rabbits or something. Or you were. Last Saturday. Out on his lawn?” Another pause. “Remember, it was raining?”

A month back, two weeks ago, even, she would have felt obliged to explain herself, would have soothed and mollified and dredged up a battery of behavioral terms—proximate causation, copulation solicitation, naturalistic fallacy—to cow him, but today, under the pale sun, in the company of the pack, she just couldn’t seem to muster the energy. She might have grunted—or maybe that was only the sound of her stomach rumbling. She couldn’t remember when she’d eaten last.

The cuffs of the man’s trousers were stiffly pressed into jutting cotton prows, perfectly aligned. The bulldog began to lick at first one, then the other. There was the faintest creak of tendon and patella, and two knees presented themselves, and then a fist, pressed to the earth for balance. She saw a crisp white strip of shirt cuff, the gold flash of watch and wedding band.

“Listen,” he said, “I don’t mean to stick my nose in where it’s not wanted, and I’m sure you have your reasons for, for”—the knuckles retrenched to balance the movement of his upper body, a swing of the arm, perhaps, or a jerk of the head—“all this. I’d just say live and let live, but I can’t. And you know why not?”

She didn’t answer, though she was on the verge—there was something about his voice that was magnetic, as if it could adhere to her and pull her to her feet again—but the bulldog distracted her. He’d gone up on his hind legs with a look of unfocussed joy and begun humping the man’s leg, and her flash of epiphany deafened her to what he was saying. The bulldog had revealed his name to her: from now on she would know him as Humper.

“Because you upset my wife. You were out in our yard and I, she— Oh, Christ,” he said, “I’m going about this all wrong. Look, let me introduce myself—I’m Julian Fox. We live on B Street, 2236? We never got to meet your husband and you when you moved in. I mean, the developments got so big—and impersonal, I guess—we never had the chance. But if you ever want to stop by, maybe for tea, a drink—the two of you, I mean—that would be, well, that would be great.”

She was upright and smiling, though her posture was terrible and she carried her own smell with her into the sterile sanctum of the house. He caught it immediately, unmistakably, and so did Cara, judging from the look on her face as she took the girl’s hand. It was as if a breeze had wafted up from the bog they were draining over on G Street to make way for the tennis courts; the door stood open, and here was a raw infusion of the wild. Or the kennel. That was Cara’s take on it, delivered in a stage whisper on the far side of the swinging doors to the kitchen as she fussed with the hors d’oeuvres and he poured vodka for the husband and tap water for the girl: She smells like she’s been sleeping in a kennel. When he handed her the glass, he saw that there was dirt under her nails. Her hair shone with grease and there were bits of fluff or lint or something flecking the coils of it where it lay massed on her shoulders. Cara tried to draw her into small talk, but she wouldn’t draw—she just kept nodding and smiling till the smile had nothing of greeting or joy left in it.

Cara had got their number from Bea Chiavone, who knew more about the business of her neighbors than a confessor, and one night last week she’d got through to the husband, who said his wife was out—which came as no surprise—but Cara had kept him on the line for a good ten minutes, digging for all she was worth, until he finally accepted the invitation to their “little cocktail party.” Julian was doubtful, but before he’d had a chance to comb his hair or get his jacket on, the bell was ringing and there they were, the two of them, arm in arm on the doormat, half an hour early.

The husband, Don, was acceptable enough. Early thirties, bit of a paunch, his hair gone in a tonsure. He was a computer engineer. Worked for I.B.M. “Really?” Julian said. “Well, you must know Charlie Hsiu, then—he’s at the Yorktown office?”

Don gave him a blank look.

“He lives just up the street. I mean, I could give him a call, if, if—” He never finished the thought. Cara had gone to the door to greet Ben and Julie Ober, and the girl, left alone, had migrated to the corner by the rubber plant, where she seemed to be bent over now, sniffing at the potting soil. He tried not to stare—tried to hold the husband’s eye and absorb what he was saying about interoffice politics and his own role on the research end of things (“I guess I’m what you’d call the ultimate computer geek, never really get away from the monitor long enough to put a name to a face”)—but he couldn’t help stealing a glance under cover of the Obers’ entrance. Ben was glad-handing, his voice booming, Cara was cooing something to Julie, and the girl (the husband had introduced her as Cynthia, but she’d murmured, “Call me C.f., capital ‘C,’ lowercase ‘f’ ”) had gone down on her knees beside the plant. He saw her wet a finger, dip it into the soil, and bring it to her mouth.

While the La Portes—Cara’s friends, dull as woodchips—came smirking through the door, expecting a freak show, Julian tipped back his glass and crossed the room to the girl. She was intent on the plant, rotating the terra-cotta pot to examine the saucer beneath it, on all fours now, her face close to the carpet. He cleared his throat, but she didn’t respond. He watched the back of her head a moment, struck by the way her hair curtained her face and spilled down the rigid struts of her arms. She was dressed all in black, in a ribbed turtleneck, grass-stained jeans, and a pair of canvas sneakers that were worn through at the heels. She wasn’t wearing socks, or, as far as he could see, a brassiere, either. But she’d clean up nicely, that was what he was thinking—she had a shape to her, anybody could see that, and eyes that could burn holes right through you. “So,” he heard himself say, even as Ben’s voice rose to a crescendo at the other end of the room, “you, uh, like houseplants?”

She made no effort to hide what she was doing, whatever it may have been—studying the weave of the carpet, looking at the alignment of the baseboard, inspecting for termites, who could say?—but instead turned to gaze up at him for the first time. “I hope you don’t mind my asking,” she said in her hush of a voice, “but did you ever have a dog here?”

He stood looking down at her, gripping his drink, feeling awkward and foolish in his own house. He was thinking of Seymour (or “See More,” because as a pup he was always running off after things in the distance), picturing him now for the first time in how many years? Something passed through him then, a pang of regret carried in his blood, in his neurons: Seymour. He’d almost succeeded in forgetting him. “Yes,” he said. “How did you know?”

She smiled. She was leaning back against the wall now, cradling her knees in the net of her interwoven fingers. “I’ve been training myself. My senses, I mean.” She paused, still smiling up at him. “Did you know that when the Ninemile wolves came down into Montana from Alberta they were following scent trails laid down years before? Think about it. All that weather, the seasons, trees falling and decaying. Can you imagine that?”

“Cara’s allergic,” he said. “I mean, that’s why we had to get rid of him. Seymour. His name was Seymour.”

There was a long braying burst of laughter from Ben Ober, who had an arm round Don’s shoulder and was painting something in the air with a stiffened forefinger. Cara stood just beyond him, with the La Portes, her face glowing as if it had been basted. Celia La Porte looked from him to the girl and back again, then arched her eyebrows wittily and raised her long-stemmed glass of Viognier, as if toasting him. All three of them burst into laughter. Julian turned his back.

“You didn’t take him to the pound—did you?” The girl’s eyes went flat. “Because that’s a death sentence, I hope you realize that.”

“Cara found a home for him.”

They both looked to Cara then, her shining face, her anchorwoman’s hair. “I’m sure,” the girl said.

“No, really. She did.”

The girl shrugged, looked away from him. “It doesn’t matter,” she said with a flare of anger. “Dogs are just slaves, anyway.”

The Reverend Singh had wanted to return to the site the following afternoon and excavate the den, convinced that these furtive night creatures were in fact human children, children abducted from their cradles and living under the dominion of beasts—unbaptized and unsaved, their eternal souls at risk—but urgent business called him away to the south. When he returned, late in the evening, ten days later, he sat over a dinner of cooked vegetables, rice, and dal, and listened as Chunarem told him of the wolf bitch that had haunted the village two years back, after her pups had been removed from a den in the forest and sold for a few annas apiece at the Khuar market. She could be seen as dusk fell, her dugs swollen and glistening with extruded milk, her eyes shining with an unearthly blue light against the backdrop of the forest. People threw stones, but she never flinched. And she howled all night from the fringes of the village, howled so that it seemed she was inside the walls of every hut simultaneously, crooning her sorrow into the ears of each sleeping villager. The village dogs kept hard by, and those that didn’t were found in the morning, their throats torn out. “It was she,” the Reverend exclaimed, setting down his plate as the candles guttered and moths beat at the netting. “She was the abductress—it’s as plain as morning.”

A few days later, he got up a party that included several railway men and returned to the termite mound, bent on rescue. In place of the rifle, he carried a stout cudgel cut from a mahua branch. He brought along a weighted net as well. The sun hung overhead. All was still. And then the hired beaters started in, the noise of them racketing through the trees, coming closer and closer until they converged on the site, driving hares and bandicoot rats and the occasional gaur before them. The railway men tensed in the machan, their rifles trained on the entrance to the burrow, while Reverend Singh stood by with a party of diggers to effect the rescue when the time came. It was unlikely that the wolves would have been abroad in daylight, and so it was no surprise to the Reverend that no large animal was seen to run before the beaters and seek the shelter of the den. “Very well,” he said, giving the signal, “I am satisfied. Commence the digging.”

As soon as the blades of the first shovels struck the mound, a protracted snarling could be heard emanating from the depths of the burrow. After a few minutes of the tribesmen’s digging, the she-wolf sprang out at them, ears flattened to her head, teeth flashing. One of the diggers went for her with his spear just as the railway men opened fire from the machan and turned her, snapping, on her own wounds; a moment later, she lay stretched out dead in the dust of the laterite clay. In a trice the burrow was uncovered, and there they were, the spirits made flesh, huddled in a defensive posture with the two wolf cubs, snarling and panicked, scrabbling at the clay with their broken nails to dig themselves deeper. The tribesmen dropped their shovels and ran, panicked themselves, even as the Reverend Singh eased himself down into the hole and tried to separate child from wolf.

The larger of the children, her hair a feral cap that masked her features, came at him biting and scratching, and finally he had no recourse but to throw his net over the pullulating bodies and restrain each of the creatures separately in one of the long, winding gelaps the local tribesmen use for winter wear. On inspection, it was determined that the children were females, aged approximately three and six, of native stock, and apparently, judging from the dissimilarity of their features, unrelated. The she-wolf, it seemed, had abducted the children on separate occasions, perhaps even from separate locales, and over the course of some time. Was this the bereaved bitch that Chunarem had reported? the Reverend wondered. Was she acting out of a desire for revenge? Or merely trying, in her own unknowable way, to replace what had been taken from her and ease the burden of her heart?

In any case, he had the children confined to a pen so that he could observe them, before caging them in the back of the bullock cart for the trip to Midnapore and the orphanage, where he planned to baptize and civilize them. He spent three full days studying them and taking notes. He saw that they persisted in going on all fours, as if they didn’t know any other way, and that they fled from sunlight as if it were an instrument of torture. They thrust forward to lap water like the beasts of the forest and took nothing in their mouths but bits of twig and stone. At night they came to life and stalked the enclosure with shining eyes like the bhuts that half the villagers still believed them to be. They did not know any of the languages of the human species, but communicated with each other—and with their sibling wolves—in a series of grunts, snarls, and whimpers. When the moon rose, they sat on their haunches and howled.

It was Mrs. Singh who named them, some weeks later. They were pitiful, filthy, soiled with their own urine and excrement, undernourished, and undersized. They had to be caged to keep them from harming the other children, and Mrs. Singh, though it broke her heart to do it, ordered them put in restraints, so that the filth and the animal smell could be washed from them, even as their heads were shaved to defeat the ticks and fleas they’d inherited from the only mother they’d ever known. “They need delicate names,” Mrs. Singh told her husband, “names to reflect the beauty and propriety they will grow into.” She named the younger sister Amala, after a bright-yellow flower native to Bengal, and the elder Kamala, after the lotus that blossoms deep in the jungle pools.

The sun stroked her like a hand, penetrated and massaged the dark yellowing contusion that had sprouted on the left side of her rib cage. Her bones felt as if they were about to crack open and deliver their marrow and her heart was still pounding, but at least she was here, among the dogs, at rest. It was June, the season of pollen, the air supercharged with the scents of flowering, seeding, fruiting, and there were rabbits and squirrels everywhere. She lay prone at the lip of the den and watched the pups—long-muzzled like their mother and brindled Afghan peach and husky silver—as they worried a flap of skin and fur that Snout had peeled off the hot black glistening surface of the road and dropped at their feet. She was trying to focus on the dogs—on A1, curled up nose to tail in the trampled weed after regurgitating a mash of kibble for the pups, on Decidedly, his eyes half closed as currents of air brought him messages from afar, on Humper and Factitious—but she couldn’t let go of the pain in her ribs and what that pain foreshadowed from the human side of things.

“Oh, God! Here comes little Miss Perky.”

Don had kicked her. Don had climbed out of the car, crossed the field, and stood over her in his suede computer-engineer’s ankle boots with the waffle bottoms and reinforced toes and lectured her while the dogs slunk low and rumbled deep in their throats. And, as his voice had grown louder, so, too, had the dogs’ voices, until they were a chorus commenting on the ebb and flow of the action. When was she going to get her ass up out of the dirt and act like a normal human being? That was what he wanted to know. When was she going to cook a meal, run the vacuum, do the wash—his underwear, for Christ’s sake? He was wearing dirty underwear, did she know that?

She had been lying stretched out flat on the mound, just as she was now. She glanced up at him as the dogs did, taking in a piece of him at a time, no direct stares, no challenges. “All I want,” she said, over the chorus of growls and low, warning barks, “is to be left alone.”

“Left alone?” His voice tightened in a little yelp. “Left alone? You need help, that’s what you need. You need a shrink, you know that?”

She didn’t reply. She let the pack speak for her. The rumble of their response, the flattened ears and stiffened tails, the sharp, savage gleam of their eyes should have been enough, but Don wasn’t attuned. The sun seeped into her. A grasshopper she’d been idly watching as it bent a dandelion under its weight suddenly took flight, right past her face, and it seemed the most natural thing in the world to snap at it and break it between her teeth.

Don let out some sort of exclamation—“My God, what are you doing? Get up out of that, get up out of that now!”—and it didn’t help matters. The dogs closed in. They were fierce now, barking in savage recusancy, their emotions twisted in a single cord. But this was Don, she kept telling herself, Don from grad school, bright and buoyant Don, her mate, her husband, and what harm was there in that? He wanted her back home, back in the den, and that was his right. The only thing was, she wasn’t going.

“This isn’t research. This is bullshit. Look at you!”

“No,” she said, giving him a lazy, sidelong look, though her heart was racing, “it’s dog shit. It’s on your shoes, Don. It’s in your face. In your precious computer—”

That was when he’d kicked her. Twice, three times, maybe. Kicked her in the ribs as if he were driving a ball over an imaginary set of uprights in the distance, kicked and kicked again—before the dogs went for him. A1 came in first, tearing at a spot just above his right knee, and then Humper, the bulldog who, she now knew, belonged to the feathery old lady up the block, got hold of his pant leg while Barely went for the crotch. Don screamed and thrashed, all right—he was a big animal, two hundred and ten pounds, heavier by far than any of the dogs—and he threatened in his big animal voice and fought back with all the violence of his big animal limbs, but he backed off quickly enough, threatening still, as he made his way across the field and into the car. She heard the door slam, heard the motor scream, and then there was the last thing she heard: Snout barking at the wheels as they revolved and took Don down the street and out of her life.

“You know he’s locked her out, don’t you?”

“Who?” Though he knew perfectly well.

“Don. I’m talking about Don and the dog lady?”

There was the table, made of walnut varnished a century before, the crystal vase full of flowers, the speckless china, the meat, the vegetables, the pasta. Softly, so softly he could barely hear it, there was Bach, too, piano pieces—partitas—and the smell of the fresh-cut flowers.

“Nobody knows where she’s staying, unless it’s out in the trash or the weeds or wherever. She’s like a bag lady or something. Bea said Jerrilyn Hunter said she saw her going through the trash one morning. Do you hear me? Are you even listening?”

“I don’t know. Yeah. Yeah, I am.” He’d been reading lately. About dogs. Half a shelf of books from the library in their plastic covers—behavior, breeds, courting, mating, whelping. He excised a piece of steak and lifted it to his lips. “Did you hear the Leibowitzes’ Afghan had puppies?”

“Puppies? What in God’s name are you talking about?” Her face was like a burr under the waistband, an irritant, something that needed to be removed and crushed.

“Only the alpha couple gets to breed. You know that, right? And so that would be the husky and the Leibowitzes’ Afghan, and I don’t know who the husky belongs to—but they’re cute, real cute.”

“You haven’t been—? Don’t tell me. Julian, use your sense: she’s out of her mind. You want to know what else Bea said?”

“The alpha bitch,” he said, and he didn’t know why he was telling her this, “she’ll actually hunt down and kill the pups of any other female in the pack who might have got pregnant, a survival-of-the-fittest kind of thing—”

“She’s crazy, bonkers, out of her fucking mind, Julian. They’re going to have her committed, you know that? If this keeps up. And it will keep up, won’t it, Julian? Won’t it?”

At first they would take nothing but raw milk. The wolf pups, from which they’d been separated for reasons both of sanitation and acculturation, eagerly fed on milk-and-rice pap in their kennel in one of the outbuildings, but neither of the girls would touch the pan-warmed milk or rice or the stewed vegetables that Mrs. Singh provided, even at night, when they were most active and their eyes spoke a language of desire all their own. Each morning and each evening before retiring, she would place a bowl on the floor in front of them, trying to tempt them with biscuits, confections, even a bit of boiled meat, though the Singhs were vegetarians themselves and repudiated the slaughter of animals for any purpose. The girls drew back into the recesses of the pen the Reverend had constructed in the orphanage’s common room, showing their teeth. Days passed. They grew weaker. He tried to force-feed them balls of rice, but they scratched and tore at him with their nails and their teeth, setting up such a furious caterwauling of hisses, barks, and snarls as to give rise to rumors among the servants that he was torturing them. Finally, in resignation, and though it was a risk to the security of the entire orphanage, he left the door to the pen open in the hope that the girls, on seeing the other small children at play and at dinner, would soften.

In the meantime, though the girls grew increasingly lethargic—or perhaps because of this—the Reverend was able to make a close and telling examination of their physiology and habits. Their means of locomotion had transformed their bodies in a peculiar way. For one thing, they had developed thick pads of callus at their elbows and knees, and toes of abnormal strength and inflexibility—indeed, when their feet were placed flat on the ground, all five toes stood up at a sharp angle. Their waists were narrow and extraordinarily supple, like a dog’s, and their necks dense with the muscle that had accrued there as a result of leading with their heads. And they were fast, preternaturally fast, and stronger by far than any other children of their respective ages that the Reverend and his wife had ever seen. In his diary, for the sake of posterity, the Reverend noted it all down.

Still, all the notes in the world wouldn’t matter a whit if the wolf children didn’t end their hunger strike, if that was what this was, and the Reverend and his wife had begun to lose hope for them, when the larger one—the one who would become known as Kamala—finally asserted herself. It was early in the evening, the day after the Reverend had ordered the door to the pen left open, and the children were eating their evening meal while Mrs. Singh and one of the servants looked on and the Reverend settled in with his pipe on the veranda. The weather was typical for Bengal in that season, the evening heavy and close, every living thing locked in the grip of the heat, and all the mission’s doors and windows standing open to receive even the faintest breath of a breeze. Suddenly, without warning, Kamala bolted out of the pen, through the door, and across the courtyard to where the orphanage dogs were being fed scraps of uncooked meat, gristle, and bone left over from the preparation of the servants’ meal, and before anyone could stop her she was down among them, slashing with her teeth, fighting off even the biggest and most aggressive of them until she’d bolted the red meat and carried off the long, hoofed shin-bone of a gaur to gnaw in the farthest corner of her pen.

“I really appreciate this …”

And so the Singhs, though it revolted them, fed the girls on raw meat until the crisis had passed, and then they gave them broth, which the girls lapped from their bowls, and finally meat that had been at least partially cooked. As for clothing—clothing for decency’s sake—the girls rejected it as unnatural and confining, tearing any garment from their backs and limbs with their teeth, until Mrs. Singh hit on the idea of fashioning each of them a single tight-fitting strip of cloth they wore knotted round the waist and drawn up over their privates, a kind of diaper or loincloth they were forever soiling with their waste. It wasn’t an ideal solution, but the Singhs were patient—the girls had suffered a kind of deprivation no other humans had ever suffered—and they understood that the ascent to civilization and light would be steep and long.

When Amala died, shortly after the wolf pups had succumbed to what the Reverend presumed was distemper communicated through the orphanage dogs, her sister wouldn’t let anyone approach the body. Looking back on it, the Reverend would see this as Kamala’s most human moment—she was grieving, grieving because she had a soul, because she’d been baptized before the Lord and was no wolfling or jungle bhut but a human child after all, and here was the proof of it. But poor Amala. Her, they hadn’t been able to save. Both girls had been dosed with sulfur powder, which caused them to expel a knot of roundworms up to six inches in length and as thick as the Reverend’s little finger, but the treatment was perhaps too harsh for the three-year-old, who was suffering from fever and dysentery at the same time. She’d seemed all right, feverish but calm, and Mrs. Singh had tended her through the afternoon and evening. But when the Reverend’s wife came into the pen in the morning Kamala flew at her, raking her arms and legs and driving her back from the straw in which her sister’s cold body lay stretched out like a figure carved of wood. They restrained the girl and removed the corpse. Then Mrs. Singh retired to bandage her wounds and the Reverend locked the door of the pen to prevent any further violence. All that day, Kamala lay immobile in the shadows at the back of the pen, wrapped in her own limbs. When night fell, she sat back on her haunches behind the rigid geometry of the bars and began to howl, softly at first, and then with increasing force and plangency until it was the very sound of desolation itself, rising up out of the compound to chase through the streets of the village and into the jungle beyond.

The sky was clear all the way to the top of everything, the sun so thick in the trees that he thought it would catch there and congeal among the motionless leaves. He didn’t know what prompted him to do it, exactly, but as he came across the field he balanced first on one leg and then the other, to remove his shoes and socks. The grass—the weeds, wildflowers, puffs of mushroom, clover, swaths of moss—felt clean and cool against the lazy progress of his bare feet. Things rose up to greet him, things and smells he’d forgotten all about, and he took his time among them, moving forward only to be distracted again and again. He found her, finally, in the tall nodding weeds that concealed the entrance of the den, playing with the puppies. He didn’t say hello, didn’t say anything—just settled in on the mound beside her and let the pups surge into his arms. The pack barely raised its collective head.

Her eyes came to him and went away again. She was smiling, a loose, private smile that curled the corners of her mouth and lifted up into the smooth soft terrain of the silken skin under her eyes. Her clothes barely covered her anymore, the turtleneck torn at the throat and sagging across one clavicle, the black jeans hacked off crudely—or maybe chewed off—at the peaks of her thighs. The sneakers were gone altogether, and he saw that the pale-yellow soles of her feet were hard with callus, and her hair—her hair was struck with sun and shining with the natural oil of her scalp.

He’d come with the vague idea—or, no, the very specific idea—of asking her for one of the pups, but now he didn’t know if that would do, exactly. She would tell him that the pups weren’t hers to give, that they belonged to the pack, and though each of the pack’s members had a bed and a bowl of kibble awaiting it in one of the equitable houses of the alphabetical grid of the development springing up around them, they were free here, and the pups, at least, were slaves to no one. He felt the thrusting wet snouts of the creatures in his lap, the surge of their animacy, the softness of the stroked ears, and the prick of the milk teeth, and he smelled them, too, an authentic smell compounded of dirt, urine, saliva, and something else also: the unalloyed sweetness of life. After a while, he removed his shirt, and so what if the pups carried it off like a prize? The sun blessed him. He loosened his belt, gave himself some breathing room. He looked at her, stretched out beside him, at the lean, tanned, running length of her, and he heard himself say, finally, “Nice day, isn’t it?”

“Don’t talk,” she said. “You’ll spoil it.”

“Right,” he said. “Right. You’re right.”

And then she rolled over, bare flesh from the worried waistband of her cutoffs to the dimple of her breastbone and her breasts caught somewhere in between, under the yielding fabric. She was warm, warm as a fresh-drawn bath, the touch of her communicating everything to him, and the smell of her, too—he let his hand go up under the flap of material and roam over her breasts, and then he bent closer, sniffing.

Her eyes were fixed on his. She didn’t say anything, but a low throaty rumble escaped her throat.

The Reverend Singh sat there on the veranda, waiting for the rains. He’d set his notebook aside, and now he leaned back in the wicker chair and pulled meditatively at his pipe. The children were at play in the courtyard, an array of flashing limbs and animated faces, attended by their high, bright catcalls and shouts. The heat had loosened its grip ever so perceptibly, and they were, all of them, better for it. Except Kamala. She was indifferent. The chill of winter, the damp of the rains, the full merciless sway of the sun—it was all the same to her. His eyes came to rest on her where she lay across the courtyard in a stripe of sunlight, curled in the dirt with her knees drawn up beneath her and her chin resting atop the cradle of her crossed wrists. He watched her for a long while as she lay motionless there, no more aware of what she was than a dog or an ass, and he felt defeated, defeated and depressed. But then one of the children called out in a voice fluid with joy, a moment of triumph in a game among them, and the Reverend couldn’t help but shift his eyes and look.

(Some details here are from Charles MacLean’s The Wolf Children: Fact or Fantasy? and Wolf-Children and Feral Man, by the Reverend J. A. L. Singh and Robert M. Zingg.)

| 2002 |

“Now play dead.”

BEN McGRATH

If you find yourself on the service road of the Major Deegan, in the shadow of the Cross Bronx Expressway, between the train tracks and the Harlem River, and you hear loud barking interspersed with the crowing of roosters, do not be alarmed. Follow your ears (and the flies) to the chain-link fence, and, while noting the “No Trespassing” and “Beware of Dog” signs, introduce yourself politely to whoever might be sitting nearby, at the entrance of what appears to be a canine shantytown—plywood huts, wire cages, tarps, and assorted vehicles packed into half an acre near the base of High Bridge.

The land belongs to the New Tabernacle Baptist Church, which for the past eleven years has run a kind of nonprofit kennel club for urban hunting dogs, carrying on a local, word-of-mouth tradition that dates to around the Second World War. A New Tabernacle volunteer named Lewis Jones (everyone calls him Lou) serves as the chief groundskeeper, tending to, among other things, a charred mound of beer cans that passes for a waste-disposal system. Fifteen dog shanties house about fifty beagles, coon hounds, and Italian mastiffs. At one point, the kennel had an official name—the Highbridge Hunting Club—but its charter has lapsed. The dogs’ owners do not pay rent, although donations to the church are encouraged.

One afternoon last week, a man named Peppy (Lou calls him Lucky) was sitting on a rusty bench while facing a pen full of mastiffs that were pawing aggressively at the gate. “These are guard dogs,” he said. “The rest are bird dogs, rabbit dogs.” (Lou says that the mastiffs are for “hunting the big game, like lions and tigers.”) A few roosters wandered around freely, speaking their minds. Peppy had on a green T-shirt with a picture of a snarling dog and the words “Remington Steel: We breed with overseas methods.” He said that he’d been raising dogs in the Bronx for almost two years—an arriviste. “There’s not too many places in the city you can keep dogs,” Peppy said. “If you’re into hunting, you heard of this place.”

Soon, Peppy’s business partner, Ross, arrived, carrying a couple of boxes of syringes, for applying tick and flea repellent. The two men opened the nearest padlock and began attending to their pooches, the most stubborn of whom was named Isabella. A couple of albino cats prowled the perimeter. The roosters kept crowing. “Cats came, I guess, because of the rats,” Ross said. “See, the rats will come to try to eat the dog food.”

“Got rats down here about the size of an arm,” Peppy said. “Cats eat the rats.”

“I guess it’s just a nature thing,” Ross said.

And the roosters? “That’s old hunting tradition,” Peppy said. “It’s a Southern thing.”

Guests are not common, and the conversation proceeds at a languid pace. “The A.S.P.C.A. comes down sometimes,” Peppy said. “Sanitation comes by to see that it don’t smell.” Occasionally, someone from a rowing club upriver will wander by, having beached at a wet-weather discharge station near the Metro-North rail yards.

“One guy approached us—he wanted to bring some pits,” Ross said, referring to pit bulls. “We try to steer clear of that.”

“He might be Michael Vick-in’ it,” Peppy said, referring to the Atlanta Falcons quarterback, who has been indicted on charges of helping to run a dogfighting ring. (Last week, Vick pleaded not guilty.) Peppy and Ross’s dogs don’t fight, they said, but they do compete. Ross used to breed “Rotts”—Rottweilers. Now he prefers Cane Corsos, a variety of Italian mastiff. “They’re the No. 1 guard dog in the world,” he said. He also enters them in events organized by the Protection Sports Association. “You got ‘weight pull,’ ‘hard catch,’ ” he said. Then he described an event in which a man hides behind a tepee and, on command, a dog charges and lunges for the man’s arm. Isabella paced and drooled.

A recent visitor, still bewildered upon leaving such a place (the nearest subway stop is twenty-five minutes away on foot, across multiple highways), tried recounting his experience—the hounds, the roosters, the cats, the tepee—to Joseph Pentangelo, a local A.S.P.C.A. official. “You sound like you went to Oz,” he said, and added, “You’re not allowed to own roosters in New York City.” He wasn’t aware of the New Tabernacle kennel, but he mentioned that the week before he’d been called to retrieve a horse that had got loose on Pelham Parkway. “This guy appeared to be squatting, keeping it as a pet,” Pentangelo said. “He’d made this stable using the box from a delivery truck, and then he fashioned a corral out of wire and police barricade and pickle barrels.”

| 2007 |

GEORGE W. S. TROW

Right this minute (if you will join us in the historical present), we are in the Eugenia Room of Sardi’s. What a treat. Not many actors physically in sight, although plenty of ghosts. Instead, we see dozens of dog fanciers (members of the Dog Fanciers Club), wonderful and exciting pictorial representations of dogs displayed on stands, a few pieces of dog sculpture standing on their own, and, above all these (like classical busts in a Grinling Gibbons room), pictures from what we have come to think of as Sardi’s Permanent Collection—i.e., the real stuff. We start with one of Michael Redgrave, by Don Bevan. “Dear Sardi’s, I am happy to be here among my friends” is the inscription.

The dog fanciers also seem to be happy to be with one another. Their club has been in existence for about thirty years. It used to meet at various restaurants, even at the old Statler, but for the last fifteen years it has met exclusively at Sardi’s. For a time, the dog fanciers just talked about dogs—American Kennel Club rules and things like that—but three years ago Howard Atlee, the club president, decided that their meetings needed what he calls “event identity,” and so now they have an annual show of dog art, and judge the art, and the winning artists receive five hundred dollars and are invited to donate their objects to the Dog Museum, in St. Louis. In order that this story won’t be threaded through with unnecessary suspense, we can say that the winners this year are Stumped, by Harry C. Weber, which is a bronze sculpture of two Jack Russells writhing around in the wilderness; Champion American Bull Terrier, by Babette Joan Kiesel, which is a straightforward portrait; The Party, by Jodi Hudspeth, which is a bronze sculpture of three Yorkshire terriers having a kind of birthday party, with a gift box and dog bones and a ball and another small thing, maybe a book, in the foreground; and Autumn Beauty, by Stephen J. Hubbell, which is an oil on canvas of a debonair English setter.

O.K. Now we’re back in the Eugenia Room. After looking up at Michael Redgrave, we walked cautiously around. We admired a piece of sculpture called Sighthound, by Kathleen O’Bryan Hedges, from Great Falls, Virginia. Sighthound was very thin and silvery. Then we heard another piece being described as “Matissey” and “Cézanney,” and we kept right on going. We talked to Mr. Atlee. “Most people have a picture of a dog, even if they don’t have a dog,” he said. We have no idea if this is true. Mr. Atlee looked just like Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird as he said it. We were told that Ellen Fisch, who lives in Hew-lett, Long Island, and has painted a portrait of Ranger, the Queen Mother’s Welsh corgi, and presented it at Clarence House, was there. But we didn’t meet her. We did meet Mrs. Edward L. Stone, a distinguished-looking woman, who was one of the judges.

Then we met a real dog fancier, a woman with long dark hair. “Are you fond of dogs?” we asked, because we noticed that she was staring intently at Sighthound.

“I live for my dog,” she said simply.

“What sort of dog do you have?” we asked.

“A Maltese,” she said, and then she tried to clarify for us her relationship to the dog world. “There are things I don’t do,” she said. “I don’t travel to Far Hills in the driving rain so that my dog can compete with other dogs. On the other hand, I do do a lot of what you might call doting. I pay a lot of attention to how my dog’s hair is washed and cut. On the other hand, I don’t act as a chaperon for my dog.”

We asked her what she meant by “chaperon.”

“Well,” she said, “it’s like children’s social life, where your parents pay for you to go, and you have to go and say hello to the ones brought by other parents.”

We said that she seemed to be talking from the dog’s point of view.

“Yes, that’s what I do do,” the woman said.

Then we looked at a painting of a huge white dog walking in a vast area of pale-green-and-amber grass. The artist was Patrick McManus, and quite soon we found ourself talking to him.

“What sort of dog is it?” we asked.

“It’s a whippet. It needs to be hung in a room bigger than this one.”

“What other kinds of work do you do?”

“I do this. I live hand to mouth. I was a construction worker at one time. I’m a recluse. I don’t come out too often.” He introduced us to his girlfriend, Baby. “I also write songs and write for a dog magazine,” he said.

Lunch was served. There were eleven tables of dog fanciers. There were party favors on the tables donated by J-B Wholesale Pet Supplies, Inc. One of them was a yellow rubber lion. “A pet would be afraid of it,” someone said. We looked over at the head table. There were Mr. Atlee and Mrs. Stone and also Captain Arthur J. Haggerty, who is a famous dog trainer and is famous in another way, too—for looking like Mr. Clean, the cleanser man. He has a big, very bald head.

“I’ve just been to the Dog Museum, in St. Louis,” the woman sitting next to us said. “They just built a new wing. I saw forty years of Snoopy. Snoopy, I thought. Anyway, it’s a fine museum.”

Two of the judges made speeches. Howard Atlee was at the microphone a lot as he introduced people. He announced the winners. We had a chance to have another talk with the serious dog fancier who thinks from the dog’s point of view. We asked her what she most liked about the Dog Fanciers Club.

“Well, my favorite book is dedicated to one of the founders of the club,” she said. “I can tell you are going to ask what my favorite book is. It’s The Complete Maltese, by Nicholas Cutillo. It’s not an old book, but it deals with antiquity. The Maltese is a very old breed.”

“Antiquity?” we asked.

“Antiquity. Mr. Cutillo quotes the Roman poet Martial, who wrote about a Maltese who belonged to a Roman governor of Malta. The Maltese was named Issa. I happen to be able to quote you part of what Martial wrote. He said, ’Issa is more frolicsome than Catullus’ sparrow. Issa is purer than a dove’s kiss. Issa is gentler than a maiden, Issa is more precious than Indian gems.’ I find that to be very moving. My Maltese is more frolicsome than a sparrow, as a matter of fact. I love the name Issa. If I had read this epigram before I named my Maltese, I might have named her Issa. By the way, the epigram ends ‘Lest the last days that she sees the light should snatch her from him forever, Publius had her picture painted.’ So that justifies the idea of painting a dog’s picture.”

We were going to ask this serious dog fancier what name she did give her Maltese, but before we could she turned around and disappeared from the Eugenia Room.

We asked Patrick McManus if he ever painted anything other than dogs.

“I did a whole series of construction workers when I was a construction worker,” he said.

| 1990 |