Elaine Ostrander, a geneticist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in Seattle, is awakened each morning around seven by Tess, her purebred Border collie. When I spoke with Ostrander not long ago, a steady cold rain was falling, but the weather had not deterred her and Tess from their morning ritual in a park near her house. Ostrander runs Tess hard for fifteen minutes, and then they play for fifteen minutes, with Ostrander throwing a ball to the far end of a field, and Tess fetching it. Border collies are herding dogs, bred for alertness, focus, and determination. “They like to be kept busy,” Ostrander says. “She needs to burn off her early-morning energy.” They return home, clean off the park mud, and go together to the Hutchinson Center. Ostrander’s laboratory there has all the standard steel and enamel fittings of molecular biology, including high-speed centrifuges, DNA sequencers, and P.C.R. machines. The only clue to her particular specialty comes from the art on the laboratory walls: framed prints and photographs of dogs. Tess nestles into her place on the floor next to Ostrander’s desk. When a visitor enters, Tess gets up and approaches. “She helps keep order in the laboratory,” Ostrander says. “She herds my students and postdocs.”

A forty-year-old woman with straight brown hair and sharp green eyes, Elaine Ostrander, along with a small network of colleagues and collaborators, is mapping the dog genome. The DNA of dog and that of man are sufficiently alike so that gene maps of inherited canine diseases will help identify the genes for their human counterparts. Moreover, the dog genome promises to help with the search for the genetic basis of behavior. Purebred dogs have distinct temperaments, and with an accurate map the genes that determine their behavior can be identified—telling us what makes, say, Border collies like Tess so attentive, tenacious, and goal-driven. By contrast, cowering huskies and snappish spaniels may hold clues to treating psychiatric disorders in human beings. People and their pets, it turns out, may resemble each other even more than you’d think.

Dogs, as a species, were created by man. In the standard Darwinian model, natural forces in the wild would have selected for the perpetuation of those genes that favored survival and procreation. But dogs came into being through a process of artificial selection, when human beings, probably around a hundred thousand years ago, began to domesticate gray wolves into Canis familiaris. Man bred these animals to suit his work purposes and to be compatible with his social structures and his social behavior. Canines were trained to serve as hunters, trackers, herders, and sentinels, as well as playmates for children and companions for adults. The lives of man and dog became so closely integrated that we began to breed them for behaviors that were functional surrogates of our own. In the ancient Middle East, where grain was cultivated and livestock was husbanded, people bred dogs that had protective instincts. During the Middle Ages in Europe, many dogs were bred in monasteries, with preference given to traits seen as Christian, such as loyalty, cooperation, and affection. And over the past century man has shaped canine evolution even more systematically, by establishing breeds that meet kennel-club standards.

The way to select for prized physical and behavioral attributes—the ability to hunt foxes, say, or to guide the blind—is tight inbreeding. A chosen sire is often mated within a closed gene pool, and sometimes within its family: fathers may be paired with daughters, or brothers with sisters. But, although inbreeding of this sort preserves the desired trait, it also brings together dangerous recessive genes, which are normally diluted by mating outside the family. After several generations of inbreeding, valued lines of purebred show and performance dogs frequently develop serious physical ailments and behavioral disorders.

For a medical geneticist, these problems present an opportunity. Many of the hereditary canine illnesses have close human analogues. But they’re vastly easier to find and study in dogs. Purebred dogs are far more genetically homogeneous than any human population, and that makes it easier to trace and identify recessive genes in them. You can amplify recessive traits by directed breeding, and, since dogs produce many more offspring than people do, it’s easier to study how different disease-linked genes interact. And, of course, research into behavioral genetics has come to rely heavily upon separated-at-birth siblings—a circumstance that is the norm with puppies but not with people.

Elaine Ostrander and Mark Neff, her collaborator at Berkeley, recently produced a map of the dog genome. It is being used to find the mutations responsible for a host of canine diseases: boxers with progressive weakness of the heart muscle, or cardiomyopathy; keeshonden with holes in the septum of the heart and a misshapen aorta, a condition called tetrology of Fallot; spaniels with spinal muscular atrophy, a degenerative neurological disease; Scottish terriers and chihuahuas with myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disorder; and beagles and St. Bernards with epilepsy. Each of these dog disorders corresponds to a human one.

Greg Acland, a veterinary ophthalmologist and geneticist at Cornell, is using the map to investigate canine blindness. I recently watched Acland, an Australian with the blunt language, and girth, of an aging rugby player, as he examined one of his research subjects. The dog was mid-sized, with a rich mahogany coat, but I couldn’t identify the breed. “The blindness gene we’re studying originated in a line of Irish setters, and that accounts for the coloring,” Acland told me. “We used beagles to crossbreed with the setters. Beagles have great personalities, are very fertile, and easily adapt to life in a colony. The gene turns up several generations later.”

As Acland approached the dog from the side, there was no reaction. Only when he was directly in front of the dog did it raise its head and move its snout to sniff. “The dog with retinal atrophy follows the same course as people with retinitis pigmentosa,” Acland explained, referring to the most common cause of inherited human blindness, which currently affects perhaps a hundred thousand Americans. “First, there is loss of night vision, then loss of peripheral perception—that’s called tunnel vision. Only very late is there complete blindness.” Acland’s dog was in the tunnel-vision stage. The kinds of dogs that are bred to serve as guide dogs for the blind are confident, flexible, and loyal, but some of them are also prone to retinal atrophy; sometimes such a dog will suffer the fate of its master. Since to breed and train such a dog costs between thirty and forty thousand dollars, the disorder has important economic ramifications. But the main impetus of Acland’s work is to speed the search for blindness genes in man.

The first dog gene that will directly illuminate the pathology of a human disease may well be the one for narcolepsy. “We are close—it’ll be a few months to a year,” Dr. Emmanuel Mignot, a psychiatrist and the director of Stanford University’s Narcolepsy Center, told me in ebullient, French-accented English. “The symptoms and signs of narcolepsy are so similar in dog and man it’s scary.”

Narcolepsy is a sleep disorder that affects about one in every two thousand Americans. It usually develops during adolescence, causing excessive daytime sleepiness, and it is frequently missed by physicians, who mistakenly ascribe the symptoms to teenage ennui, late-night parties, or covert drug use. In one study, the average time from the onset of symptoms to its diagnosis was fourteen years. Patients have abnormal REM sleep, and they suffer “hypnagogic,” or dreamlike, auditory and visual hallucinations while they’re dozing. The signature manifestation of narcolepsy is cataplexy—a sudden loss of muscular control which can last several seconds or several minutes. An episode is often triggered by pleasurable emotions: a narcoleptic might start laughing at a good joke and abruptly crumple to the floor.

“You realize they won’t know the difference.”

Dr. Mignot oversees Stanford’s colony of twenty-seven narcoleptic Doberman pinschers. As far as I could tell, his Dobermans looked like any others, with their fearsome visage, deep-brown eyes trained forward, sharp ears raised in surveillance. I observed a group of five Dobermans moving with typical tightly coiled grace, and then saw them fed—presented with the rare treat of beefsteak. After the first bite, the dogs dropped suddenly, their limbs sprawling, their heads lolling back. “We stimulate the Dobermans with an excellent cuisine,” Dr. Mignot explained. “They experience the pleasure of the good food. And then they collapse.” Those sleek, muscular creatures now looked like rag dolls tossed on the floor.

“It is a nightmare to look for a gene like this in humans,” Dr. Mignot went on to say. “There are not enough families with several affected individuals.” Once Mignot and his team at Stanford started using pedigree studies to study canine narcolepsy, they made the surprising discovery that canine narcolepsy seems to result from a single mutant gene.

“Our analysis of the region on the Doberman’s chromosome and on the human chromosome shows them to be virtually identical,” Dr. Mignot said. This means that once the dog gene is identified the human mutation will be easily pinpointed by the use of sequencing data from the Doberman study. The mystery of how a single gene can so alter cerebral function as to induce sleepiness, vivid hallucinations, and motor paralysis may soon be explained. Although finding a gene doesn’t mean finding a treatment, it does mean that researchers can work back from the root cause. The mutant gene may be linked to a mutant protein, and a drug may be developed to correct for it.

Although narcolepsy appears to be caused by a single gene, the distinct personalities of purebred dogs are polygenic, which is to say that they are determined by many genes acting in concert. And “personalities” is surely the right term: the way dogs act can seem eerily similar to the way we act, as the result of both domestication and our propensity for projecting our emotions upon our pets. The desirable temperament of each breed in the American Kennel Club’s Complete Dog Book, the bible of pedigrees, is elaborately anthropomorphic: boxers are meant to be “alert, dignified and self-assured,” and, in the show ring, “should exhibit constrained animation”; rottweilers are “calm, confident and courageous,” and exude “self-assured aloofness”; mastiffs display “grandeur and good nature … dignity rather than gaiety.” The task of sorting out such polygenic traits isn’t simple, but it helps to be able to study them in laboratory populations that can be inbred and crossbred.

While Ostrander is studying DNA sequences, Greg Acland, at Cornell, and Karen Overall, the director of the Behavior Clinic at the University of Pennsylvania Veterinary School, are working with groups of dogs in order to identify the genes that are responsible for several “neurotic” canine lines. Overall, a petite forty-three-year-old woman with waist-long blond hair, cool blue eyes, and glasses, is a veterinarian with expertise in both behavioral psychology and evolutionary biology, and she speaks with the sharp cadences of a rigorous experimentalist. Her work helped establish diagnostic criteria in animal behavior and led to the recent F.D.A. approval of Clomicalm, a psychotropic drug for dogs with separation anxiety—what headline writers dubbed “puppy Prozac.”

Acland’s and Overall’s research has focussed on nervous pointers and shy Siberian huskies; doctors at the University of Pennsylvania are also studying bullterriers, fox terriers, and German shepherds, all of which exhibit obsessive-compulsive behavior—they may spend hours chasing their tails—and a line of English springer spaniels with poor impulse control: they react aggressively and capriciously to one another and to their handlers. “Breeders don’t realize that when they select for refined forms of physical carriage those attributes are linked to behavioral genes,” Karen Overall says. For example, the English springers bred for show promenade with their heads far forward, in an almost lunging posture. Several genes are believed to work together to produce such an appearance and gait, and they could include those which, in the species’ evolutionary history, are linked to hunting and attacking. Hence the springer spaniels with impulsive aggression.

Among many huskies, such side effects of selection seem to have resulted in shyness. “The Siberian husky has a very special social structure,” Acland says. “The Jack London myth—that in the Arctic you need a wolf dog, a primitive alpha male—is a lot of garbage. A good sled dog exhibits harmony. You need teamwork. The dog has to be rotated from the harness at the front of the sled, or it will become exhausted. There can’t be fighting for position among the dogs, but deference.” So the painful shyness could be an exaggerated expression of selected deference. Acland has bred a colony of husky crossbreeds in Pennsylvania, descendants of a Siberian husky named Earl. “He was a handsome, lovely dog, donated by a breeder who noticed that he was painfully shy,” Acland says. The dog was comfortable with his owner; his extreme bashfulness emerged only when he encountered a stranger. “People like that trait,” Acland notes. “It reinforces the feeling, ‘This is my dog.’ ”

To study how the genes for shyness were inherited, the researchers mated Earl with a female beagle. The offspring included a female that was then mated with an unrelated male beagle. Among that dog’s offspring were two very shy males. “This experiment shows, to a rough approximation, that shyness appears to be transmitted as a dominant trait,” Acland says. But he emphasizes that the behavior is complex. There are different degrees of shyness in purebred huskies and in the offspring outbred with beagles, just as there are in people. “It’s not binary,” Acland says, “but a continuous, quantitative function of several genes.”

If sled dogs are bred for team-spiritedness, pointers are bred to have a rigid posture and a tense focus, and the occasional appearance of “nervous” pointers seems to be a result. The pointers that Acland and Overall study are descended from a colony that was maintained at the University of Arkansas, in Fayetteville, in the early 1970s. “They were found by Pavlovian psychiatrists looking for natural animal models of neurosis,” Karen Overall says. “The doctors hoped they could condition against the avoidance response, but it didn’t succeed in these pointers.”

In a spacious state-of-the-art facility at the University of Pennsylvania, nervous pointers and their unaffected littermates are housed together. The mid-sized, brown-and-white dogs occupy large, comfortable metal-mesh cages, with special vinyl floors so their paws are not trapped or irritated. There are long, broad runs for regular exercise. The cages are cleaned two or three times a day, and a staff of seasoned handlers scrupulously attends to the animals, providing both grooming and affection.

When Greg Acland approached an affected pointer, the dog was startled, its wary eyes widening and its jaw tightening. He entered the dog’s cage and extended a comforting hand, but the pointer froze in place, its wiry body rigid and statue-still. The prominent flank muscles trembled visibly. Acland affectionately stroked the dog’s side, but the animal only became more distressed. As he gently patted the pointer’s head, it panicked, and assumed a wide-splayed stance, its front feet extending forward and its back arching. During a four-minute encounter, the pointer was mute, emitting not a bark or a squeal. After Acland left the cage, the dog stayed frozen for a little while. Only with measured caution did it turn its head to confirm Acland’s exit. Blood samples obtained immediately after such interactions show high levels of cortisol, an adrenal stress hormone, and the release of muscle enzymes from the uncontrolled muscle shaking.

The pointer’s littermates, though they have been reared in the same environment, have a completely different response. After sniffing Acland’s hand, they responded eagerly to his affectionate gestures, barking at the caresses and tousling of their fur. They followed him as he walked toward the cage’s exit, seeking more play, and barking loudly to protest his departure.

The shy huskies, descendants of Earl and unaffected dogs, have different signs of anxiety from those of nervous pointers. As Greg Acland approached a shy female, the animal did not immediately freeze but skulked to the back of the cage—“like a wallflower at a party,” he said. The husky turned her distinctive black-and-white lupine head away from Acland, while watching him out of the corner of her eye. As Acland extended his hand, the husky quickly lowered her head and retreated further, cowering behind her frisky littermates. The dog’s limbs began to tremble, and saliva poured from her clenched mouth. Acland moved his hand closer and spoke in a friendly voice. The shy husky dodged the gesture, digging her white hind legs into the floor and pressing her broad black flanks forcefully against the back wall of the cage.

“They are both anxious, but there are differences,” Acland told me later. The shy husky, over time, has become comfortable with her daily handler. The nervous pointer has never done so, despite the best efforts of the regular caretakers. “It’s hard to develop empathy with the affected pointers,” Acland admitted. “They isolate themselves because of their anxiety and are never happy with anybody.” He said that when he is directly in front of a dog and is trying to make eye contact “the pointer has a peculiar face, like an owl’s—he stares right through you.”

“We’re always leery of making glib associations, but these responses in the nervous pointer and in the shy Siberian husky resemble forms of human anxiety disorders,” Karen Overall said. In fact, when a measured amount of lactate, a harmless acidic solution, is given to the nervous pointers or the shy Siberian huskies, it triggers a state of uncontrolled anxiety—which is what the solution does in people with certain panic disorders. This suggests that a similar neurochemistry is at work in dogs and human beings.

“The genetic basis of these anxiety behaviors in dogs is complex,” Overall told me, “and will not be solved as quickly as single-gene traits, like narcolepsy.” But she believes that the dog research will be “priceless” for human psychiatry. She pointed out that primitive areas deep in the mammalian brain in canines and Homo sapiens are similar and have changed little in the course of evolution. “It is in these ancestral areas of the mammalian brain that studies of behavior in the dog will be most informative,” she said. In human beings, a number of behavioral and affective disorders—panic attacks, outbursts of aggression, extreme anxiety—seem to involve various primitive sites, such as the caudate nucleus, the amygdala, and the hippocampus.

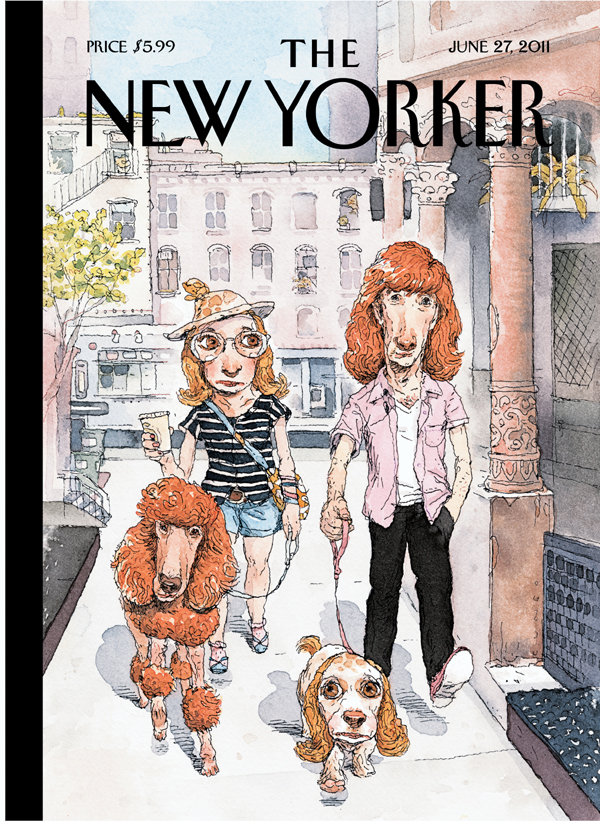

Whatever results come from Karen Overall’s cages and Elaine Ostrander’s DNA sequencers aren’t likely to settle all our long-standing arguments about character and free will. And yet their genetic and biochemical findings will sharply focus these discussions. Though nearly everyone accepts the notion that the carriage and the personality of dogs arise from their breeding, there’s no such consensus when it comes to our own propensities. We mostly prefer to imagine ourselves untethered by such twists of DNA. Still, Greg Acland, for one, seems to be reconciled to the idea. “Everyone who deals with dogs accepts our compatibility, accepts how owners resemble their breeds,” he says. “Nobody wants to hear that when you grow up you turn into your father and mother. The older you get, though, the more you realize it’s true.”

| 1999 |

“Is the homework fresh?”