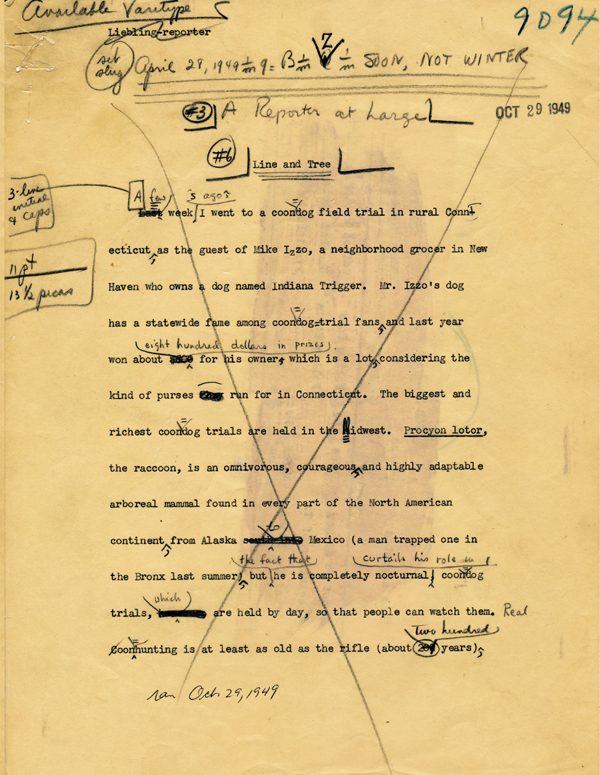

Some time ago, I went to a coondog field trial in rural Connecticut as the guest of Mike Izzo, a neighborhood grocer in New Haven who owns a notable dog named Indiana Trigger. Mr. Izzo’s dog has a statewide fame among coondog-trial fans, and last year won about five hundred dollars in prizes for his owner, which is a lot, considering the size of the purses run for in Connecticut. (The biggest and richest coondog trials are held in the Midwest.) Procyon lotor, the raccoon, is an omnivorous, courageous, and highly adaptable arboreal mammal found in every part of the North American continent, from Alaska to Mexico (a man trapped one in Brooklyn last spring), but the fact that he is almost completely nocturnal curtails his role in coondog trials, which are held by day, so that people can watch them. Coon-hunting is at least as old as the rifle (about two hundred years), but field trials, which are a combination of a drag hunt and a race, have been in favor only since around 1925. Their increasing popularity has brought about a bifurcation in the coondog business, much like the one that occurred, by slow stages, in the barber-surgeon’s trade in the late Middle Ages, when practitioners who lacked fluency in conversation or a light hand at shaving turned to what seemed a less exacting specialty. “Night dogs,” those used in the darkling pursuit of the wild raccoon, are often not much good at field trials. Many of the best field-trial dogs have never been hunted in the woods at night, and never will be, because they might there develop habits of ponderation that would unfit them for their purpose, which is the rapid pursuit of the obvious.

In a coondog trial, a sack filled with litter from a captive raccoon’s kennel is dragged over a cross-country course a couple of miles long, ending at a tree in the upper branches of which a live raccoon in a cage has been placed. The dogs are usually let loose ten at a time at the starting line. A hundred and fifty feet from the tree with the raccoon in it, the course passes between a pair of flags, customarily nothing more than white rags tied to saplings, seventy-five feet apart. The first dog to pass between the flags is said to win “line,” and the next dog “second line.” Dogs that run outside the flags are disqualified. The first dog to spot the raccoon up the tree and bark at him as if he means it wins “tree.” There are generally about a dozen qualifying heats in trials of the size that are run in Connecticut, and after the last one the winners compete in a tree final, a line final, and a second-line final. The finals are run on other courses than the heats, so the dogs won’t be aided by memory. The bag of litter is hauled over the track after each heat, so the scent will not go cold. Consequently, night-dog men say, a dog doesn’t need much of a nose to follow it. In a real night hunt, a dog must sometimes follow a trail several hours old. On the other hand, a trial dog needs a lot more speed than a straight cooner. The publics for the two forms of the sport are separate but overlap. A man putting a dog in a trial pays an entry fee, usually three dollars, and all the prizes come out of the pooled fees. When a hundred dogs are entered, the finals for line and tree are worth about fifty dollars apiece.

Although an urban, non-arboreal, mammal myself, I got so interested in field trials after attending several last fall that I subscribed to a remarkable monthly called Full Cry, published in Sedalia, Missouri, which carries a schedule of trials as long as the list of books in the Fall Announcement number of Publishers’ Weekly. It was from Full Cry that I learned about the field trial I attended with Mr. Izzo, at Southington, about twenty miles from New Haven. Mr. Izzo’s acquaintance I made a year ago, at a trial near Baltic, a mill town not far from Norwich. (One of the minor advantages of following coondog trials is that you get to know geography in detail.) I arrived at Mr. Izzo’s house, in New Haven, at five minutes to ten on a Sunday morning, and found him already in an aged two-door sedan, with three dogs loaded in a low trailer hitched on behind. Mr. Izzo is a stocky, sallow man in his late forties, who has a heavy, Roman-legionary jaw and wears steel-rimmed spectacles. The other human members of our party were Mrs. Izzo, a tiny, lively woman wearing slacks and high-heeled shoes; a coondog fancier named Jack Galligan, who works for the New Haven Bridge Department; and a twelve-year-old boy whom Izzo introduced as Mrs. Izzo’s nephew, Junior Matrianno. Mr. Galligan, who looks like a ruddier, jowlier version of Al Smith, is one of those Irishmen who go in for mock solemnity, mock ferocity, and slow, reassuring winks. He has been a coondog man for nearly forty years, but he finds cooning at night a bit too rough for him now, and so sticks to trials. Last year, when I first met him, he had no trial dog, but he now informed me that he had acquired one, and that it was in the trailer with Indiana Trigger and another belonging to Izzo.

After we had all fitted ourselves into the car, we started out, the three dogs barking as if the sedan were a coon and they had hopes of catching it. “Trigger and Jiggs start barking as soon as they see the trailer,” said Izzo, who was driving. Jiggs is his second-string dog, a youngster he got for nothing out of a dog pound a year and a half ago. (There is no such thing as a pure coonhound breed; any dog that will hunt coon or follow a trail with acumen and enthusiasm can be called a coonhound.) “My dog is the one with the beautiful voice on him,” Galligan said. “He’s a registered bluetick, but the man down in Tennessee that sold him to the fellow I bought him off of won’t let go of the papers. The only thing I don’t know is what will he do. He’s never run in a trial before.” A bluetick is predominantly white but flecked and mottled with a smoky blue. A setter with this marking is known, I believe, as a belton, and a horse as a blue roan.

There had been rain earlier in the morning, and the air was warm and moist. “The scent will be plain today,” Galligan said. “No breeze to turn over the leaves.” When the air is moist, the scent lies close to the ground and lasts longer. After we had gone about ten miles, Izzo drove into a large field by the side of a wood and we let the dogs out for a breather. Indiana Trigger, whom I had seen run twice before, is a small, compact black hound, with tan on face and breast. He hasn’t the long, drooping ears of the classic black-and-tan type, but he is recognizably a hound dog. Galligan told me that Trigger had been whelped somewhere in the South and had been sold for ten dollars by the man who bred him, and then had passed through the hands of a dozen owners on his way North, each selling him at a profit. When he got to Indiana, a man paid a hundred and twenty-five dollars for him and then sold him to Izzo for two hundred and fifty, after he had failed to win anything with the dog. “He’s been running better for Mike than he ever did for anybody else,” Galligan said. “He run maybe thirty times last year and was only beaten before the finals twice. That’s the way with dogs. Sometimes they improve with a change of owners and sometimes they go sour.” Galligan’s Blue, the putative bluetick, also looked like a hound. But Jiggs, a long-legged dog with medium-length reddish hair, was simply and happily a cur. Junior Matrianno, speaking as a loyal friend of Jiggs’, told me the dog was “shepherd and bull.” Izzo said, more dispassionately, “He could be anything.” The ability to follow a trail by scent is a hound characteristic, but dogs like Jiggs, with forthright native talent, keep coondog trials a highly democratic sport. After the dogs had taken their ease for a few minutes, Izzo called them. Jiggs and Trigger came lolloping back and hopped into the trailer. Blue was a bit hesitant.

Soon after we had passed through Cheshire, which is not far from Southington, we began to look for road signs that would indicate the way to the field trial. Trials are always held in thinly settled sections of townships, because the dogs need a lot of ground to run over. The routes leading to them are posted with cardboard signs bearing red arrows and the name of a dog-food company, which distributes them, on request, to field-trial sponsors. Sometimes the dog-food people give a free sack of food to every dog entered. We soon picked up the arrows, and after passing a couple of dairy farms that Galligan said belonged to famous coon-hunters we turned off the highway and onto a gravel road that led up the side of a long hill covered with spruce, hemlock, and hardwood trees. The top of the hill was a plateau, and ten or fifteen automobiles were already parked on it, most of them with dogs tethered to their bumpers. Other dogs were tied to trees, just out of reach of one another, and still others were being walked on leashes. Most of them howled in greeting as we arrived with our trailer, and Izzo, steering a course neatly among them, drove to a vacant spot near a tree, where we climbed out and disembarked our three dogs.

Galligan put a leash on Blue, and he and I took a walk around while Izzo moored Jiggs and Trigger. Blue stopped in front of a large, gaunt, anxious-looking, biscuit-colored middle-aged hound that was holding one forepaw off the ground. Galligan, carefully keeping Blue out of the old dog’s reach, said to me, “There’s a dog that win some of the biggest races in the East a couple of years ago, but he hurt his foot, and he’s an adder now.” “What’s an adder?” I asked, as I was expected to, and Galligan said, “Puts down three and carries one.” At that moment, the adder’s owner, a very fat man in a green shirt, came up and shouted to Galligan, “Well, well, ain’t seen you since what you done in Dalton, Mass.!” “What did he do in Dalton, Mass.?” I asked, since I was plainly supposed to play straight man. “Went into a strange church and passed the basket!” the fat man shouted, and immediately burst into loud laughter. “Never mind,” said Galligan. “I never picked up no butts from the ground, like I seen you do.” “I was just picking them up for you—get more flavor that way,” his friend came back. Galligan laughed hard. “He’s a witty fellow, that Warren,” he said to me as we walked away. “Hell of a witty fellow.”

Cars were arriving on the plateau in a steady stream now, and the majority of them were towing dog trailers. Most of the dogs looked like hounds, but usually like hounds with traces of sheep dog, bull terrier, or whippet. There was one coarse collie that showed no trace of anything else, and a number of sheep dogs and unclassifiable curs that might possibly have had a recessive dash of hound. The fastest pure-strain dogs—greyhounds and whippets—are no good for trials, because their instinct is to run with their heads high and their eyes on the quarry, making no effort to use their noses. These traits, the product of centuries of breeding, cannot be altered by any simple attempt at reeducation. Crosses between greyhounds or whippets and proved coonhounds—the result of one-generation attempts to combine a nose and speed—are seen at tracks, but they seldom work out; the dogs seem to be torn between conflicting inherited aptitudes. “I still think a hound with a good cat foot—a dog that stands high on his toes—is fast enough to beat any of them crosses,” Galligan said. “The crosses run wide on the turns and have to wait for the dogs with noses to pick up the scent again. Look at the feet on Blue, now. I think he’s got a future.”

The Southington Sportsmen’s Club, which owns the hillside over which the dogs were to run, is a member of the United Raccoon Hunters Field Trial and Protective Association of Connecticut. The Association makes up a regular schedule of trials, each of the member clubs holding one meet a year. A field trial gives the host club a chance to pick up a bit of cash for its treasury, the money coming from the sale of refreshments and a 30 percent cut of auction pools on the dogs, the standard form of betting on coondog trials. The members’ wives in charge of the feeding arrangements remind one of the committeewomen at any church clambake; in fact, they are the women who run the church clambake when that event comes along. A field trial combines aspects of a church affair and of a very small race meeting, but it has an entirely individual sound accompaniment—the continual howls, barks, and snarls of the parliament of coon-dogs. Coondog men, incidentally, pay much attention to the noise their dogs make, and speak learnedly of “bawl-and-chops,” “squall-and-chops,” “long bawls,” “short bawls,” and “long bass bugles.” Some dogs, known as silent trailers, steal up on a raccoon and give tongue only after they have treed him. They are deprecated by coonhunting aesthetes.

For silent dogs don’t give a thrill:

With them it’s two barks, then a kill,

a poet wrote in Full Cry. I attended a meet last year with a man who bought a dog on the spot for no other reason than that it had a beautiful baritone voice. It turned out that its gifts were exclusively vocal, so my friend sold it as a foxhound. “I didn’t know but what he might be,” he told me. “He certainly wasn’t interested in coon.”

The Southington clubhouse is a one-room structure, built of gray concrete blocks, on the slope of the hill just below the edge of the plateau. Under the downhill side of the clubhouse, there is an open basement, which serves as a restaurant, selling hamburgers, hot dogs, steamed clams, clam chowder, clam broth, raw onions, apples, pickles, coffee, birch beer, root beer, home-baked pies, a meat-loaf dinner for a dollar, and a number of other items that I forget. There was a beer bar outside. Hard liquor is sold at some trials, but none was evident at Southington, except in the gaits of a few of the sportsmen.

As it got on toward twelve o’clock, the members of the committee running the trial began to appeal to owners over a public-address system to get their entries in. The entry lists had been open since ten o’clock, the grounds were packed with dogs, but only a few owners had paid their three dollars and put down their dogs’ names. “Hanging back to see if they can get in a soft heat,” Izzo said to me. “They want to wait until all the hot dogs are drawn.” I asked him if he had entered Jiggs and Trigger yet, and he said he hadn’t—he wanted to have a look at the lists first.

While the dog-owners were outwaiting one another, I stopped at the lunch counter for a moment to deal with a bottle of birch beer, a hamburger with raw onion, and a portion of steamed clams, and then went to look at the finish line of the course, in a field bounded by a low stone wall halfway down the hill. The starting line was about two miles away somewhere; the dogs in each heat would be taken to it in a pickup truck. A dog running through the flags of the finish line and continuing straight on could hardly fail, it would seem, to come right up against the coon tree, a tall walnut, alone amid low spruce. The coon, in his cage, was already up in the crotch of a limb, about thirty feet above the ground, and the countryman who had put him there, probably a veteran bird’s-nester, was already down. “I hope the boys get a lighter coon next time they hold a race,” he said to me. “Nearly ruptured myself lugging him up there.” As we talked, the track-layers, a couple of boys in their early teens, came into view, walking cater-cornered through the field, dragging the sack of coon litter behind them. They were completing a sidehill scramble through briars and over fences, across pasture land and wood lots. On their way, they had marked their course by tying rags to trees, so that the sack could be hauled over the same trail after each heat. The boys walked across the line midway between the flags and then marched up to the tree in which the coon was perched. They smacked the bag vigorously against the trunk several times, then held it clear of the ground and walked over to us. They said they expected to go over the course a couple more times during the afternoon; other pairs of boys would spell them. “In some Western states, they allow you to drag a live coon along the trail in a wet bag,” the tree-climber said, “but here the Humane Society won’t let you. It doesn’t make much difference, because even if you had a live coon, a good coondog could smell that there had been a man along there—man scent and coon scent all mixed together for two miles. He would know it wasn’t on the level. You ask me, there are mighty few of these dogs that are fooled into thinking they’re hunting a coon. They know it’s just a race.”

I climbed back up the hill and found that a set of dogs had at last been drawn for the first heat. Each dog is given a number when he is entered, and white clay marbles bearing corresponding numbers are put in a wire basket, from which ten at a time are rolled out to determine the starters in each heat. Galligan’s Blue and Izzo’s Jiggs had both been drawn for the first heat.

Dan Cole, a familiar figure at Connecticut field trials, was mounting a sort of stage near the clubhouse to run the first auction pool. Cole, an extremely fat man with a handsome, incongruously young face, was wearing a pale-gray sombrero and a flame-red cotton shirt. He lives in Shelton, not far from Southington, and spends every Sunday (and a good many Saturdays) auctioning pools at Connecticut meets. Once a year, he runs a trial of his own, near Shelton. He is a prosperous farmer and is said to own a number of highly talented gamecocks. He sometimes gets a fee from the clubs for whom he officiates as auctioneer, but often waives it when a trial doesn’t draw well. Mostly, I suspect, he likes the authority he feels when he stands on the rostrum and wheedles the crowd into betting its money. His chief rival in this section is a fellow named Shorty Griffen, a railroad freight clerk from Poughkeepsie, whose style is modelled on that of the tobacco auctioneers on the radio. He chants more than Cole and wisecracks less.

The principle of an auction pool is simple: If you fancy a dog’s chances, you try to “buy” him, and if there are others of the same opinion, they bid against you. The high bidder pays his money and gets a ticket. If there are ten dogs in a heat and they are bid in for a total of twenty dollars on tree, say, the holder of the ticket on the winning dog gets the pool (minus the sponsoring club’s 30 percent cut), or fourteen dollars. Trial running isn’t really a big-money sport, but since there are separate pools for tree, line, and second line in each heat, the home club may turn a profit of several hundred dollars during the afternoon if bidding is lively. The heaviest pools are those on the finals. In the preliminaries, the bidding sometimes starts at half a dollar, and not infrequently stops there. In such cases, it is always the owner who puts up the fifty cents. It is a point of honor to have four bits’ worth of faith in your own dog. Favored dogs sometimes sell for seven or eight dollars but anything over five dollars is considered a stiff bid. In finals, dogs are occasionally bid in for as much as fifteen dollars.

Each time Cole called out the name and number of a dog, a man with a dog on leash would step out of the crowd and come up to the platform. Sometimes the dog would jump up on the platform (this usually indicates an experienced trial dog), and the man would stand beside it while Dan made his spiel. At other times, the owner would have to lift the dog onto the platform and sit with him, stroking him or clasping a fraternal arm about him to keep him calm. “Fred Clark’s Rosie dog, one of the fastest track dogs in the East,” Dan began. “Here’s a dog that can really pour it on, gentlemen. Don’t let her run in on you and then come around and say you weren’t looking or that I didn’t give you fair warning. Who’ll start her at four dollars? Three I’ve got over there—three. Who’ll say a half?…” The next dog was a tall, gangling newcomer, and Dan said, “Here’s a good tree dog, gentlemen. I can see it. If he runs in, he can look into that cage …” Later, confronted with a grizzled shepherd, plainly nine or ten years old, he began, “Don’t be influenced by the dog’s appearance, friends. He’s had experience. His owner lives just over the hill—had him over the course six times last night. The owner says half a dollar. Hello, Pete, you old chicken fighter [to a friend whom he sees studying the dog with a speculative expression], I want you to get back the money you lost on them chickens last week—say a dollar …”

“Schmooze!”

A colored man named Yager, who lives in Poughkeepsie, turns up at almost all the Connecticut meets with a trailer full of dogs as well as with a whole hunch of sons and daughters—his dog-handlers. He is very serious about the business, and last year told me that he had just given up a good house in Poughkeepsie because it was too near the center of town for his dogs. He had moved to an isolated farm on a dirt road, where he could exercise them behind the family car every day without fear of having them run over. In “roading” dogs, a trainer keeps his car at about twenty miles an hour, occasionally speeding up to thirty or thirty-two for a short stretch. Yager had a bitch at Southington that Cole had never seen before, and when she was brought up to the platform, Dan asked, “Will she tree?” (Some young dogs who have learned enough to race for line think the event is over when they have crossed it.) “She have,” Yager answered noncommittally. A coondog man named Ham Fish, a dairy farmer who keeps a big string of night dogs and trial dogs, next appeared, with a new dog that had a scarred head. “Will that dog fight?” Cole asked. “Might,” said Fish, who looks like a robust version of Ernie Pyle. A fighting dog is, of course, a poor betting proposition, since he may stop racing and start fighting. Most fights, however, occur under the tree, and a man who knows he has a fighter sometimes lets him run only for line, and then rushes out and hauls him in before he can get into trouble. The best way to take a dog out of a fight, I am informed (I have no intention of trying it), is to grab him and press with your thumbs at the rear of his jaws, against his back teeth. A patient man named Porter, whom I have seen at several trials, once told me that he had lost nine thumbnails on one talented but pugnacious dog. “He couldn’t help it,” Porter said. “He had a bull cross.”

When the last dog in the first heat had been auctioned, the crowd started down toward the coon tree and the finish line. There were almost as many women as men, most of them wearing slacks and shirts, and there seemed to be more children than adults, but this may have been an illusion caused by their greater mobility. A couple of boys were already engaged in retrieving abandoned beer bottles, which they would turn in for the two-cent deposit. They tacked about the grounds as if they, too, were trailing, and I half expected them to bawl and chop whenever they detected an empty Budweiser bottle under a bush. As the spectators trudged downhill, the voice of a club official came over the loudspeaker. “Al Rambeau,” the voice said, “catch that big white hound of yours before he gets on the track. We can’t run the heat while he is out there on the track.” A maliciously delighted dog and an unhappy human figure raced each other through the field. While this was going on, the pickup truck, with the dogs and their owners in it, set out for the starting line, heading down the hill road to the main highway. By the time we had got to the finish line, we could see the truck well along the highway; then it turned off on another side road, leading uphill.

The course is customarily laid out so that while the dogs are making a wide-arced sweep across country, the truck can double back to the finish on a more direct line by road. As soon as the dogs have started, the men jump into the truck, which then takes off at a reckless clip to get to the finishing point before the dogs. The truck stops about a hundred feet back of the coon tree, and the men hop out. The dogs are usually in sight, or at least audible, by the time the truck arrives. The owners, leashes in hand, stand ready to grab their dogs as soon as the heat has been decided, but they are not allowed to crowd the tree, because a smart dog would then run straight to his owner and bark, thus achieving a cheap victory.

At the starting point, the men lead their dogs up to the beginning of the track and let them nose around a bit. Then they unleash them, and each man hangs on to his dog by the collar or shoulder harness while the starter lines them up. Just before the start, some of the men cradle their dogs in their arms. At the whistle, these men throw their dogs forward on the trail (which can’t really help them much in a two-mile race), while others hold their dogs back for an instant. These last are the owners of young dogs who, if they got in front, might miss the track. Such dogs simply trail the seniors until they are near the line, where, stimulated by the shouts of the crowd, they sometimes run in ahead of their preceptors.

The first trial on this particular day resulted in a dead heat, a term that in this sport means mass disqualification. We could hear the dogs and then see them coming toward the finish, but about fifty yards from the line the leaders swerved, and the others followed them outside the farther flag. They ran off into the brush and then straggled back toward the crowd singly or in twos, looking for their masters. “Rabbit!” a man next to me said disgustedly. “Cottontail must have run across the course, and those so-called coondogs took its trail.” “Did not, either,” another man said. “Too many people standing that side of the course. Fool dog ran toward the people and t’others followed him. They should get the people back of that line.” Events indicated that he was probably right. In the later heats, the judges made the crowd stand back of the line, and only one or two dogs ran out during the rest of the day. Some of the owners of dogs in the first heat were wrathy, arguing that they ought to get their entry money back, inasmuch as the crowd should not have been there to distract their dogs. (In a dead heat, the auction-pool money goes to the club fund.) The official contention was that if the dogs had been following the trail by nose, as they were supposed to do, they wouldn’t have allowed themselves to be distracted. Neither Jiggs nor Blue had been among the leading dogs, so Izzo and Galligan would have lost their entry money even if the heat had been a proper one.

Before the auction for the next heat, Izzo came over to me and said in a confidential tone that a dog named Dick, a black-and-white animal that looked more like a smooth collie than anything else, was a good bet, and that he would go halves with me if I bid him in for line and tree. “A great tree dog, a great line dog. Looka those legs!” Dan Cole began when Dick’s owner, a red-faced man from Worcester, conducted him to the platform. “You know the boys didn’t bring him all the way from Massachusetts just for the ride. Four dollars. Have I got four dollars for tree?” Nobody spoke until Dan asked for a dollar; then somebody bid, and the bidding rose by bold, one-dollar leaps until four was reached, when I said, “And a half.” There was silence for a moment, and then Dan said, “Four and a half once, four and a half twice, and sold to the new convert for four and a half. Now how about line? This dog might lose tree once in a while—once in a long while—but when it comes to line, he can really fly!” I got Dick for line for five dollars.

This time, when the dogs came in sight of the finish, they were running true, headed straight for the midway point between the flags, but Dick was third as he crossed the line, with a red dog and a white one ahead of him. Having passed the line, the red dog began walking about rather aimlessly, as if he thought his work done. The white dog began investigating a small hemlock that even a fool should have realized wasn’t big enough to hold a cage with a coon in it. I could see a couple of men with leashes jumping about in high excitement, and guessed that they were the owners of the first two dogs. In such circumstances, an owner can rely only on telepathy to tell his dog which tree the coon is in. Last fall, I saw a French-Canadian mill hand stand by in mute despair during a final while a dog of his scratched his back against the coon tree and then walked away. By raising his head and barking, the dog could have earned fifty dollars for his owner. Meanwhile, Dick came loping in, ran to the foot of the walnut, jumped as high as he could against the tree, and bayed. He stayed by the tree, making a noise—I don’t know whether he was chopping or bawling—until the head tree judge blew a whistle. There are two line judges and three tree judges. Sometimes two dogs tree at almost the same time, and then a two-out-of-three vote decides. This time, however, there was no doubt. The red dog had won line and the white dog second line, but Dick had got tree. Mike and I collected $14.35 for our $9.50. We felt that we had put across a sleeper.

Before the heat Indiana Trigger was to run in, Mike came to me and said that he never liked to bet on Trigger, because when he did, the dog lost. “There’s only one in this heat I’m afraid of,” he said. “He’s a very fast line dog, but he isn’t much on tree, and if Trigger is anywhere near him, Trigger will tree first.” I bid in Trigger for tree, on my own account, and did not buy him for line. However, he fooled Mike. He was first across the line, but the second dog barked tree before he did. This contretemps cost me my winnings on Dick, plus $2.57½. The remaining heats were anticlimactic, since neither Mike nor Galligan had entries in any of them and advised no further investments. We had to stay, though, because Indiana Trigger had qualified for the line final. He had earned five dollars by winning line in his heat. Mike calculated that the prize for the final might be as much as seventy dollars.

“I’ll lay it out for you. We’re cutting back, and we no longer need a dog.”

The Izzos and Junior and I continued to walk up the hill after every heat and down the hill after every auction, but Galligan parked himself on a boulder near the finish line and remained there, talking to a couple of other sages. Blue was by this time back in the trailer, fast asleep. “He might be more of a woods dog, at that,” Galligan said. “He throws up his head every now and then and sniffs around, as if he would take an air scent. I think he might be a very good deerhound, or a fine dog after mountain lion. I think I’ll put an ad in Full Cry or the American Cooner offering him on trial.” On one of my uphill trips, I bought a dog named King Cotton, a July hound, for tree. A July is a small white hound with tan ears, looking like a straight-legged beagle or a long-eared smooth fox terrier. “This dog has never been wrong on tree in his life,” Dan said in auctioning him. King Cotton wasn’t wrong this time, either. When he got to the tree, he barked right at it. The trouble was that five or six dogs had got there before him, and at least four of them had barked on arrival. After that, I decided that it was cheaper, as well as more restful, to sit with Galligan. The sky had cleared toward noon, and the early afternoon had been hot, with swarms of little flies and gnats settling on dogs and spectators alike, but as night drew on, the air grew cooler. By the finish of the tenth heat (two more to go), it was hard to tell the dogs apart, and it was evident that the finals would have to be run in the dark.

Running trials in the dark is something that dog-owners, spectators, and particularly judges dislike, but it has come up at every meet I’ve been to. It is the subject of a long and pithy essay in an issue of the American Cooner of a few months back, by a man named Sam Hankins, a great owner of racing dogs and promoter of field trials at Hyde Park, New York. Mr. Hankins attributes the chronic lateness of dogmen at field trials principally to two causes—vice and virtue. There is one type of dogman, he says, who stays up late Saturday night drinking, always has a hangover Sunday morning, and doesn’t begin to pull himself together until noontime, after which he loads his dogs and drives fifty or a hundred miles to a trial, stopping on the way to get some breakfast and a few cans of beer. The other type likes to take his wife and children to church and then walk them home and have Sunday dinner with them. The outcome is the same, Mr. Hankins says; both types arrive at the trial at about two in the afternoon, and then they stall around waiting for the fast dogs to be drawn before they make their entries. He does not indicate whether the fellows from church are more or less ethical about this last procrastination than the boys from the tavern. There are also, Mr. Hankins says, a couple of fellows at every meet who have real night dogs that are pretty good trial dogs, too; naturally, these men try to delay matters, figuring that their dogs will have an advantage after dark. They are happy to see the meet lag and the finals run under such conditions that nobody can see what is going on. Then, Mr. Hankins continues, there are some fellows who will let their dogs go in the dark before the starting signal, meanwhile slapping their pants and whining like hounds to make the starter think they still have their dogs in hand. The most exasperating thing about late heats is that the judges are likely to call the wrong dog at the finish line, since they cannot have any lights brighter than flashlights—car headlights, for instance, would frighten the dogs back into the woods. And dog-owners are afraid that their dogs will run into trees, get hung up in fences, or start down a wrong trail and wander off, to be stolen or run over before they can be found.

It was completely dark even before the start of the last heat, and Izzo said there would be no sense watching it; the thing for us to do was to load the dogs, get into the car, and drive down to the foot of the hill. It was so late that there were to be no auction pools on the finals. The line final was to be run across woods and pastures in the valley, ending at the highway. If we parked beside the highway, the truck going out to the start would have to pass us, and Mike could stop it and get on with Trigger. We did as he suggested, and when we had parked by the dark highway, Mike began to complain about late starts and said that he had half a mind to go home rather than risk his dog. I had once seen Trigger win a line final in the dark, so I knew Mike was not serious. He got out and took Trigger from the trailer on a leash, and we all stood in the road. I asked Junior if he had done his homework, and he said “Naw!” and walked as far from me as he could get. Pretty soon we could see the lights of the dog truck coming down the hill and hear the eleven dogs in it trying to fight with each other, and their owners cursing. Mike hailed the truck and climbed aboard with Trigger. Mrs. Izzo said that there was a black dog named Cinders in the line final that seemed to be in form, and that he was an awful fast dog. A couple of minutes after the truck had gone on, we all walked over into the pasture next to the road and stood as near the finish line as a state trooper and the local town constable would let us. We could see the white flags marking the finish in the dark, but people and trees, even those within a few feet of us, were only vague masses. We knew that the line judges, one at each flag, would turn their flashlights on the first dog they saw or heard going over the line. They would hear the dogs barking as they drew near. The danger was that if the leading dog was a dark color and momentarily silent, he might sneak in on them. I stayed close by Mrs. Izzo as we stumbled through the dark. “I know Trigger’s voice when I hear it,” she said. “I’ll be able to hear him coming.” In what seemed a very short time, we heard the truck on its way back. It turned into the field and rolled in among the spectators. There were no casualties, or if there were, the victims died without a moan.

Then flashlights gleamed, and the dog-owners came rushing down off the truck. “Out with them lights!” the town constable yelled. “You want to scare them dogs back to the start?” The lights went out, and in another minute we heard the music of the dogs coming toward us in the dark. The owners were practically on the finish line this time. It didn’t make any difference now, since the dogs couldn’t see them. Someone yelled, “Here they be!” (In a lifetime of watching sporting events, I have never been the first spectator to see anything.) Then two thin beams of light shot out from the judges’ flashlights, crossing on the form of a black dog traversing the line. It was Cinders. Two dogs followed close behind him, one of whom was Trigger.

“It was a good try anyway,” Mike said after he had caught his dog. When we had got back in the car, Mrs. Izzo said, “I could tell from his bark he wasn’t in front.” Mike said, “Well, it wasn’t such a bad day. I put in six dollars in entry fees, and the Trigger win five back in heat money, but I also won two-forty betting, so I made one-forty on the day.” Junior said, “I bet Trigger will beat that Cinders by daylight.” Jack Galligan said, “I met a man here today that says he knows where there is a wonderful dog. A great big hound with claws like a cat. I bet he would make a wonderful trial dog.”

| 1949 |