Perkus Tooth, the wall-eyed former rock critic, awoke the morning after the party he vowed would be his last, the night after the worst blizzard of the winter, asleep on a staircase, already in the grip of a terrific cluster headache. He suffered these regularly, knew the drill, felt himself hunkering into the blinding, energy-sapping migraine by ancient instinct. Nobody greeted him, his hosts asleep themselves, or gone out, so he made his way downstairs, groped to locate his coat in their closet, and then found his way outdoors.

Perkus’s shoes were, of course, inadequate for the depth of freshly fallen snow. He’d have walked the eight blocks home in any event—the migraine nausea would have made a cab ride unbearable—but there wasn’t any choice. The streets were free of cabs and any other traffic. Some of the larger, better-managed buildings had had their sidewalks laboriously cleared and salted, the snow pushed into mounds covering hydrants and newspaper boxes, but elsewhere Perkus had to climb through drifts that had barely been traversed, fitting his shoes into boot prints that had been punched knee-deep. His pants were quickly soaked, and his sleeves as well, since between semi-blindness and poor footing he stumbled to his hands and knees several times before he even got to Second Avenue. Under other circumstances he’d have been pitied, perhaps offered aid, or possibly arrested for public drunkenness, but on streets the January blizzard had remade there was no one to observe him, apart from a cross-country skier who stared mercilessly from behind solar goggles, and a few dads here and there dragging kids on sleds. If they noticed him at all they probably thought he was out playing, too. There was no reason for someone to be making his way along impassable streets so early the day after. Not a single shop was open, all the entrances buried in drift.

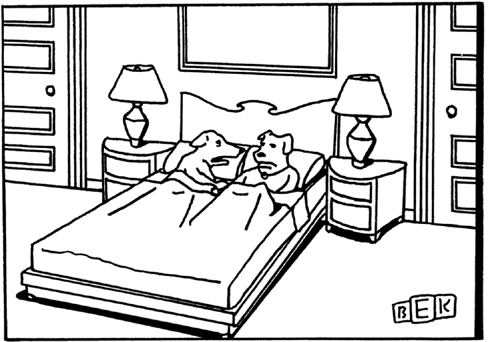

“This isn’t really about the beagles, is it.”

When he met the barricade at the corner of Eighty-fourth, he at first tried to bluster his way past, thinking the cop had misunderstood. But no. His building was one of three the snowstorm had undermined, the weight of the snow threatening the soundness of its foundation. He talked with neighbors he hadn’t spoken to in fifteen years of dwelling on the same floor, though gripped in the vise of his cluster headache he barely heard a word they said, and he couldn’t have made too good an impression. You need to find someplace to sleep tonight—that was a fragment that got through to him. They might let you in for your stuff later, but not now. You can call this number…but the number he missed. Then, as Perkus teetered away: Get yourself indoors, young man. And: Pity about that one.

Perkus Tooth had already been at a watershed, wishing to find an exit from himself, from his life and his friends, his tatter of a career—to shed it all like a snakeskin. The city in its twenty-first-century incarnation had no place for him, but it couldn’t fire him—he’d quit instead. For so many years he’d lived in his biosphere of an apartment as if it were still 1978 outside, as if placing the occasional review in the Village Voice or New York Rocker gave him credentials as a citizen of the city, but the long joke of his existence had reached its punch line. The truth was that he’d never thought of himself as a critic to begin with, more a curator. His apartment—bursting with vinyl LPs, forgotten books, binders full of zines, VHS cassettes of black-and-white films taped from PBS and Million Dollar Movie—was a cultural cache shored against time’s indifference, and Perkus had merely been its caretaker, his sporadic writings the equivalent of a catalogue listing items decidedly not for sale.

And his friends? Those among whom he wasted his days—the retired actor, now a fixture on the Upper East Side social scene; the former radical turned cynical mayor’s operative; the once aspiring investigative journalist turned hack ghostwriter—had all used up their integrity, accommodated themselves to the simulacrum that Manhattan had become. Perkus had come to an end with them, too. He needed a new life. Now, incredibly, the storm had called his bluff. This was thrilling and terrifying at once: who would he be without his apartment, without that assembly of brunching mediocrities?

There was only one haven. Perkus had one friend who was unlike the others: Biller. (Perkus had never heard a last name. Biller was just Biller.) Homeless in a Manhattan that no longer coddled the homeless, Biller was crafty, a squatter and a survivor, an underground man. Now, as if in a merciful desert vision, the information that Biller had once jotted on a scrap of receipt on Perkus’s kitchen table appeared before him: Biller’s latest digs, in the Friendreth Apartments, on Sixty-fifth near York. Perkus couldn’t remember the numerical address, but he didn’t need that; from Biller’s descriptions of the odd building and its inhabitants he’d surely be able to find it.

Yes, Biller was the one he needed now. Trudging sickened through the snowdrifts like a Napoleonic soldier in retreat from Moscow, Perkus was adequately convinced. He had got complacent in his Eighty-fourth Street apartment. Time to go off the grid. Biller knew how to do this, even in a place like Manhattan, which was nothing but grid. Biller was the essential man. They could compare notes and pool resources, Perkus preferring to think of himself as not yet completely without resources. Perkus laughed at himself now: in his thinking, Biller was becoming like Old Sneelock, in Dr. Seuss’s If I Ran the Circus, the one who’d single-handedly raise the tents, sell the pink lemonade, shovel the elephants’ shit, and also do the high-wire aerialist act. In this manner, dismal yet self-amused, Perkus propelled his body to Sixty-fifth Street, despite the headache’s dislodging him from himself, working with the only body he had—a shivering, frost-fingered, half-blind stumbler in sweat- and salt-stained party clothes.

He trailed a dog and its walker into the lobby, catching the swinging door before it clicked shut, one last act of mastery of the mechanics of outward existence, and then passed out in a melting pool on the tile just inside. Biller would later explain to Perkus that another dog walker had sought Biller out, knowing that the tall black man in the spotted fur hat functioned as ambassador for the vagabond entities sometimes seen lurking in the building, and that this tatterdemalion in the entranceway was nothing if not one of those. Biller gathered Perkus up and installed him in what he would come to know as Ava’s apartment. It was there that Perkus, nursed through the first hours by Biller’s methodical and unquestioning attentions, his clothes changed, his brow mopped, his sapped body nourished with a simple cup of ramen and beef broth, felt his new life begin.

Perkus Tooth had twenty-four hours alone in the apartment before Ava arrived. Biller kept close tabs on all the vacancies in the building and assured him that this was the best way, the intended result being that Ava would take him for granted, detect his traces on the floors and walls and in the bed and then unquestioningly settle in as a roommate. So Perkus spent the first night by himself on the surprisingly soft bed, half-awake in the dark, and then was up to pace the rooms at first light. He dwelled in the space alone just long enough to posit some conjunction between his new self—shorn of so many of its defining accoutrements, dressed in an ill-fitting, lump-

ish blue-and-orange sports sweatshirt with an iron-on decal name, presumably of some star player, his right temple throbbing with cluster, a really monstrous attack, ebbing in its fashion but still obnoxious, yet his brain also, somehow, seemed to have awoken from a long-fogging dream, a blind spot in sight, yes, but peripheral vision around the occlusion’s edges widened, refreshed—between this self and the apartment in which he’d strangely landed, the apartment that had been fitted, like his body, with hand-me-downs, furnishings that would have been rejected even by a thrift shop. The presumption was that if he puzzled at the weird decrepit prints hung over the decaying living-room set, the framed Streamers poster, or the Blue Period Picasso guitarist sun-faded to yellow over the nonworking stove in the dummy kitchen, he should be able to divine what sort of person he’d become since the last time his inquiries had turned inward. Who he was seemed actually to have slipped his mind.

Yet no. The rooms weren’t going to tell him who he was. They weren’t his. This was Ava’s apartment, only she hadn’t come yet.

Perkus hadn’t encountered another soul in the hours he’d been installed in the Friendreth, had only gazed through immovable paint-sealed windows at minute human forms picking through drifts on the Sixty-fifth Street sidewalk seven stories below, the city a distant stilled terrarium. This corner of Sixty-fifth, where the street abutted the scraps of parkland at the edge of Rockefeller University, formed an utter no man’s land in the winterscape. He listened at the walls, and through the sound of spasmodic barking imagined he heard a scrape of furniture or a groan or a sigh that could be human, but no voices to give proof, until the morning, when the volunteers began to arrive. Perkus sought to parse Biller’s words, a clustery confusion from the night before, working to grasp what form his new roommate might take, even as he heard the volunteers at individual doors, calling each apartment’s resident by name, murmuring “good boy” or “good girl” as they headed out to use the snowdrifts as a potty.

Even those voicings were faint, the stolid prewar building’s heavy lath and plaster making fine insulation, and Perkus could feel confident that he would remain undetected if he wished to be. When clunking footsteps and scrabbling paws led to his threshold, his apartment’s unlocked door opened to allow a dog and its walker through. Perkus hid like a killer in the tub, slumping down behind the shower curtain to sit within the porcelain’s cool shape. He heard Ava’s name spoken then, by a woman who, before leaving, set out a bowl of kibble and another of water on the kitchen floor, and cooed a few more of the sweet doggish nothings a canine lover coos when fingering behind an ear or under a whiskery chin. Biller’s words now retroactively assumed a coherent, four-footed shape. Perkus had never lived with a dog. But much had changed just lately, and he was open to new things. He couldn’t think of a breed to wish for but had an approximate size in mind, some scruffy mutt with the proportions of, say, a lunch pail. The door shut, and the volunteer’s footsteps quickly receded in the corridor. Perkus had done no more than rustle at the plastic curtain, preparing to hoist himself from the tub, when the divider was nudged aside by a white grinning face—slavering rubbery pink lips and dinosaur teeth hinged to a squarish ridged skull nearly the size of his own, this craned forward by a neck and shoulders of pulsing and twitching muscle. One sharp, white, pink-nailed paw curled on the tub’s edge as a tongue slapped forth and began brutalizing Perkus’s helpless lips and nostrils. Ava the pit bull greeted her roommate with grunts and slobber, her expression demonic, her green-brown eyes, rimmed in pink, showing piggish intellect and gusto, yet helpless to command her smacking, cavernous jaws. From the first instant, before he even grasped his instinctive fear, Perkus understood that Ava did her thinking with her mouth.

The next moment, falling back against the porcelain under her demonstrative assault, watching her struggle and slip as she tried, and failed, to hurtle into the tub after him, as she braced and arched on her two back legs, he saw that the one front paw with which she scrabbled was all she had for scrabbling: Ava was a three-legged dog. This fact would regularly, as it did now, give Perkus a crucial opening—his only physical edge on her, really. Ava slid awkwardly and fell on her side with a thump. Perkus managed to stand. By the time he got himself out of the tub she was on her three legs again, flinging herself upward, forcing that boxy skull, with its smooth, loose-bunching carpet of flesh, into his hands to be adored. Ava was primally terrifying, but she soon persuaded Perkus she didn’t mean to turn him into kibble. If Ava killed him it would be accidental, in seeking to stanch her emotional hungers.

“And only you can hear this whistle?”

Biller had bragged of the high living available at the Friendreth, an apartment building that had been reconfigured into a residence for masterless dogs, an act of charity by a private foundation of blue hairs. Perkus’s homeless friend had explained to him that though it was preferable that Perkus keep himself invisible, he had only to call himself a “volunteer” if anyone asked. The real volunteers had come to a tacit understanding with those, like Perkus now, who occasionally slipped into the Friendreth Canine Apartments to stealthily reside alongside the legitimate occupants. Faced head on with the ethical allegory of homeless persons sneaking into human-shaped spaces in a building reserved for abandoned dogs, the pet-rescue workers could be relied upon to defy the Friendreth Society’s mandate and let silence cover what they witnessed. Snow and cold made their sympathy that much more certain. Biller further informed Perkus that he shared the building with three other human squatters among the thirty-odd dogs, though none were on his floor or immediately above or below him. Perkus felt no eagerness to renew contact with his own species.

Those first days were all sensual intimacy, a feast of familiarization, an orgy of pair-bonding, as Perkus learned how Ava negotiated the world—or at least the apartment—and how he was to negotiate the boisterous, insatiable dog, who became a kind of new world to him. Ava’s surgery scar was clean and pink, an eight- or ten-inch seam from one shoulder blade to a point just short of where he could detect her heartbeat, at a crest of fur beneath her breast. Some veterinary surgeon had done a superlative job of sealing the joint so that she seemed like a muscular furry torpedo, missing nothing. Perkus couldn’t tell how fresh the scar was or whether Ava’s occasional stumbles indicated that she was still learning to walk on three legs—mostly she made it look natural, and never once did she wince or cringe or otherwise indicate pain, but seemed cheerfully to accept tripod status as her fate. When she exhausted herself trailing him from room to room, she’d sometimes sag against a wall or a chair. More often she leaned against Perkus, or plopped her muzzle across his thigh if he sat. Her mouth would close then, and Perkus could admire the pale brown of her liverish lips, the pinker brown of her nose, and the raw pale pink beneath her scant, stiff whiskers—the same color as her eyelids and the interior of her ears and her scar and the flesh beneath the transparent pistachio shells of her nails. The rest was albino white, save a saucer-size chocolate oval just above her tail to prove, with her hazel eyes, she was no albino. At other times, that mouth was transfixingly open. Even after he’d convinced himself that she’d never intentionally damage him with that massive trap full of erratic, sharklike teeth, Perkus found it impossible not to gaze inside and marvel at the map of pink and white and brown on her upper palate, the wild permanent grin of her throat. And when he let her win the prize she most sought—to clean his ears or neck with her tongue—he’d have a close-up view, more than he could really endure. Easier to endure was her ticklish tongue bath of his toes anytime he shed the ugly Nikes that Biller had given him, though she sometimes nipped between them with a fang in her eagerness to root out the sour traces.

Ava was a listener, not a barker. As they sat together on the sofa, Ava pawing at Perkus occasionally to keep his hands moving on her, scratching her jowls or the base of her ears or the cocoa spot above her tail, she’d also cock her head and meet his eyes and show that she, too, was monitoring the Friendreth Canine Apartments’ other dwellers and the volunteers who moved through the halls. (As Perkus studied the building’s patterns, he understood that the most certain evidence of human visitors, or other squatters, was the occasional flushing of a toilet.) Ava listened to the periodic fits of barking that possessed the building, yet felt no need to reply. Perkus thought this trait likely extended from the authority inherent in the fantastic power of her own shape, even reduced by the missing limb. He guessed she’d never met another body she couldn’t dominate, so why bark? She also liked to gaze out the window whenever he moved a chair to a place where she could make a sentry’s perch. Her vigilance was absolutely placid, yet she seemed to find some purpose in it, and could watch the street below for an hour without nodding. This was her favorite sport, apart from love.

Ava let him know they were to sleep in the bed together that first night, joining him there and, then, when he tried to cede it to her, clambering atop him on the narrow sofa to which he’d retreated, spilling her sixty or seventy writhing pounds across his body and flipping her head up under his jaw in a crass seduction. That wasn’t going to be very restful for either of them, so it was back to the twin-size mattress, where she could fit herself against his length and curl her snout around his hip bone. By the end of the second night, he had grown accustomed to her presence. If he didn’t shift his position too much in his sleep she’d still be there when dawn crept around the heavy curtains to rouse him. Often then he’d keep from stirring, ignoring the growing pressure in his bladder, balancing the comfort in Ava’s warm weight against the exhausting prospect of her grunting excitement at his waking—she was at her keenest first thing, and he suspected that, like him, she pretended to be asleep until he showed some sign. So they’d lie together both pretending. If he lasted long enough, the volunteer would come and open the door and Ava would jounce up for a walk at the call of her name (and he’d lie still until the echoes of “O.K., Ava, down, girl, down, down, down, that’s good, no, down, down, yes, I love you, too, down, down, down…” had trickled away along the corridor).

Though the gas was disabled, the Friendreth’s electricity flowed, thankfully, just as its plumbing worked. Biller provided Perkus with a hot plate on which he could boil water for coffee, and he’d have a cup in his hand by the time Ava returned from her walk. He imagined the volunteer could smell it when she opened the door. Coffee was the only constant between Perkus’s old daily routine and his new one, a kind of lens through which he contemplated his transformations. For there was no mistaking that the command had come, as in Rilke’s line: You must change your life. The physical absolutes of coexistence with the three-legged pit bull stood as the outward emblem of a new doctrine: Recover bodily prerogatives, journey into the real. The night of the blizzard and the loss of his apartment and the books and papers inside it had catapulted him into this phase. He held off interpretation for now. Until the stupendous cluster headache vanished, until he learned what Ava needed from him and how to give it, until he became self-sufficient within the Friendreth and stopped requiring Biller’s care packages of sandwiches and pints of Tropicana, interpretation could wait.

The final step between Perkus and the dog came when he assumed responsibility for Ava’s twice-daily walks. (He’d already several times scooped more kibble into her bowl, when she emptied it, having discovered the supply in the cabinet under the sink.) On the fifth day, Perkus woke refreshed and amazed, alert before his coffee, with his migraine completely vanished. He clambered out of bed and dressed in a kind of exultation that matched the dog’s own, for once. He felt sure that Ava was hoping he’d walk her. And he was tired of hiding. So he introduced himself to the volunteer at the door, and said simply that if she’d leave him the leash he’d walk Ava now and in the future. The woman, perhaps fifty, in a lumpy cloth coat, her frizzy hair bunched under a woollen cap, now fishing in a Ziploc of dog treats for one to offer to Ava, having certainly already discerned his presence from any number of clues, showed less surprise than fascination that he’d spoken to her directly. Then she stopped.

“Something wrong with your eye?”

He’d gone unseen by all but Biller for so long that her scrutiny disarmed him. Likely his unhinged eyeball signified differently now that he was out of his suits and dressed instead in homeless-man garb, featuring a two-week beard. To this kindly dog custodian it implied that Ava’s spectral cohabitant was not only poor but dissolute or deranged. A firm gaze, like a firm handshake, might be a minimum.

“From birth,” Perkus said. He tried to smile as he said it.

“It’s cold out.”

“I’ve got a coat and boots.” Biller had loaded both into the apartment’s closet, for when he’d need them.

“You can control her?”

Perkus refrained from any fancy remarks. “Yes.”

On the street, fighting for balance on the icy sidewalks, Perkus discovered what Ava’s massiveness and strength could do besides bound upward to pulse in his arms. Even on three legs, she rode and patrolled the universe within the scope of her senses, chastening poodles, pugs, Jack Russells, even causing noble rescued racetrack greyhounds to bolt, along with any cats and squirrels foolish enough to scurry through her zone. Ava had only to grin and grunt, to strain her leash one front-paw hop in their direction, and every creature bristled in fear or bogus hostility, sensing her imperial lethal force. On the street she was another dog, with little regard for Perkus except as the rudder to her sails, their affair suspended until they returned indoors. That first morning out, the glare of daylight stunned Perkus but also fed an appetite he had no idea he’d been starving. The walks became a regular highlight, twice a day, then three times, because why not? Only a minority of female dogs, he learned, bothered with marking behaviors, those scent-leavings typical of all males. Ava was in the exceptional category, hoarding her urine to squirt parsimoniously in ten or twenty different spots. Biller brought Perkus some gloves to shelter his exposed knuckles but also to protect against the chafing of Ava’s heavy woven leash, that ship’s rigging, on his landlubber palms. Perkus learned to invert a plastic baggie on his splayed fingers and deftly inside-out a curl of her waste to deposit an instant later in the nearest garbage can. Then inside, to the ceremonial hail of barking from the Friendreth’s other inhabitants, who seemed to grasp Ava’s preferential arrangement through their doors and ceilings.

“Since we’re both being honest, I should tell you I have fleas.”

It was a life of bodily immediacy. Perkus didn’t look past the next meal, the next walk, the next bowel movement (with Ava these were like a clock’s measure), the next furry, sighing caress into mutual sleep. Ava’s volunteer—her name revealed to be Sadie Zapping—poked her head in a couple of times to inquire, and once pointedly intersected with Perkus and Ava during one of their walks, startling Perkus from reverie, and making him feel, briefly, spied upon. But she seemed to take confidence enough from what she witnessed, and Perkus felt he’d been granted full stewardship.

Now the two gradually enlarged their walking orbit, steering the compass of Ava’s sniffing curiosity, around the Rockefeller campus and the Weill Cornell Medical Center, onto a bridge over the Drive, to gaze across at the permanent non sequitur of Roosevelt Island, defined for Perkus by its abandoned t.b. hospital, to which no one ever referred, certainly not the population living there and serviced by its goofy tram, as if commuting by ski lift. “No dogs allowed,” he reminded Ava every time she seemed to be contemplating that false haven. Or down First Avenue, into the lower Sixties along Second, a nefariously vague zone whose residents seemed to Perkus like zombies, beyond help.

Perkus learned to which patches of snow-scraped earth Ava craved return, a neighborhood map of invisible importances not so different, he decided, from his old paces uptown: from the magazine stand where he preferred to snag the Times, to H&H Bagels or the Jackson Hole burger mecca. Perkus never veered in the direction of Eighty-fourth Street, though, and Ava never happened to drag him there. His old life might have rearranged itself around his absence, his building reopened, his paces waiting for him to re-inhabit them—but he doubted it. Occasionally he missed a particular book, felt himself almost reaching in the Friendreth toward some blank wall as though he could pull down an oft-browsed volume and find consolation in its familiar lines. Nothing worse than this; he didn’t miss the old life in and of itself. The notion that he should cling to a mere apartment he found both pathetic and specious. Apartments came and went, that was their nature, and he’d kept that one too long, so long that he had trouble recalling himself before it. Good riddance. There was mold in the grout of the tiles around the tub which he’d never have got clean in a million years. If Ava could thrive with one forelimb gone, the seam of its removal nearly erased in her elastic hide, he could negotiate minus one apartment, and could live with the phantom limb of human interdependency that had seemingly been excised from his life at last.

Biller wasn’t a hanger-outer. He had his street scrounger’s circuit to follow, and his altruistic one, too, which included checking in with Perkus and, most days, dropping off donated items of food or clothing that he thought might fit. Otherwise, he left Perkus and Ava alone. When Perkus was drawn unexpectedly a step or two back into the human realm, it was Sadie Zapping who drew him. Sadie had other dogs in the building and still looked in from time to time, always with a treat in her palm for Ava to snort up. This day she also had a steaming to-go coffee and a grilled halved corn muffin in a grease-spotted white bag which she offered to Perkus, who accepted it, this being not a time in life of charity refused or even questioned. She asked him his name again and he said it through a mouthful of coffee-soaked crumbs.

“I thought so,” Sadie Zapping said. She plucked off her knit cap and shook loose her wild gray curls. “It took me a little while to put it together. Me and my band used to read your stuff all the time. I read you in the Voice.”

Ah. Existence confirmed, always when you least expected it. He asked the name of her band, understanding that it was the polite response to the leading remark.

“Zeroville,” she said. “Like the opposite of Alphaville, get it? You probably saw our graffiti around, even if you never heard us. Our bassist was a guy named Ed Constantine—I mean, he renamed himself that, and he used to scribble our name on every blank square inch in a ten-block radius around CBGB’s, even though we only ever played there a couple of times. We did open for Chthonic Youth once.” She plopped herself down now, on a chair in Ava’s kitchen which Perkus had never pulled out from under the table. He still used the apartment as minimally as possible, as if he were to be judged afterward on how little he’d displaced. Ava gaily smashed her square jowly head across Sadie’s lap, into her cradling hands and scrubbing fingers. “Gawd, we used to pore over those crazy posters of yours, or broadsides, if you like. You’re a lot younger-looking than I figured. We thought you were like some punk elder statesman, like the missing link to the era of Lester Bangs or Legs McNeil or what have you. It’s not like we were holding our breath waiting for you to review us or anything, but it sure was nice knowing you were out there, somebody who would have gotten our jokes if he’d had the chance. Crap, that’s another time and place, though. Look at us now.”

Sadie had begun to uncover an endearing blabbermouthedness (even when not addressing Perkus she’d give forth with a constant stream of Good girl, there you go, girl, aw, do you have an itchy ear? There you go, that’s a girl, yes, yessss, good dog, Ava, whaaata good girl you are!) but another elegist for Ye Olde Lower East Side was perhaps not precisely what the doctor ordered just now. Perkus, who didn’t really want to believe that when his audience made itself visible again it would resemble somebody’s lesbian aunt, sensed himself ready to split hairs—not so much Lester Bangs as Seymour Krim, actually—but then thought better of it. He was somewhat at a loss for diversions. He couldn’t properly claim that he had elsewhere to be.

Sadie, sensing resistance, provided her own non sequitur. “You play cribbage?”

“Sorry?”

“The card game? I’m always looking for someone with the patience and intelligence to give me a good game. Cribbage is a real winter sport, and this is a hell of a winter, don’t you think?”

With his consent, the following day Sadie Zapping arrived at the same hour, having completed her walks, and unloaded onto the kitchen table two well-worn decks of cards, a wooden cribbage board with plastic pegs, and two packets of powdered Swiss Miss. Perkus, who hated hot chocolate, said nothing and, when she served it, drained his mug. The game Sadie taught him was perfectly poised between dull and involving, as well as between skill and luck. Perkus steadily lost the first few days, then got the feel of it. Sadie sharpened, too, her best play not aroused until she felt him pushing back. They kept their talk in the arena of the local and mundane: the state of the building; the state of the streets, which had borne another two-inch snowfall, a treacherous slush carpet laid over the now seemingly permanent irregularities of black ice wherever the blizzard had been shoved aside; the ever-improving state of Perkus’s cribbage; above all, the state of Ava, who thrived on Sadie’s visits and seemed to revel in being discussed. Perkus could, as a result, tell himself that he tolerated the visits on the dog’s account. It was nearly the end of February before Sadie told him the tragedy of Ava’s fourth limb.

“I thought you knew,” she said, a defensive near-apology.

He didn’t want to appear sarcastic—did Sadie think Ava had told him?—so said nothing, and let her come out with the tale, which Sadie had spied in Ava’s paperwork upon the dog’s transfer to the canine dorm. Three-year-old Ava was a citizen of the Bronx, it turned out. She’d lived in the Sack Wern Houses, a public development in the drug dealers’ war zone of Soundview, and had been unlucky enough to rush through an ajar door and into the corridor during a police raid on the apartment next door. The policeman who’d emptied his pistol in her direction, one of three cops on the scene, misdirected all but one bullet in his panic, exploding her shank. Another cop, a dog fancier who’d cried out but failed to halt the barrage, had tended the fallen dog, who, even greeted with this injury, wanted only to beseech for love with her tongue and snout. Her owner, a Dominican who may or may not have considered his pit bull ruined for some grim atavistic purpose, balked at the expense and bother of veterinary treatment, so Ava’s fate was thrown to the kindly cop’s whims. The cop found her the best, a surgeon who knew that she’d be happier spared cycling the useless shoulder limb as it groped for a footing it could never attain, and so excised everything to the breastbone. It was the love-smitten cop who’d named her, ironically, after his daughter, whose terrified mom forbade their adopting the drooling sharky creature. So Ava came into the Friendreth Society’s care.

“He may be a fine veterinarian, but we’re going to get some funny looks.”

“She’s got hiccups,” Sadie pointed out another day, a cold one, but then they were all cold ones. “She” was forever Ava, no need to specify. The dog was their occasion and rationale, a vessel for all else unnameable that Perkus Tooth and Sadie Zapping had in common. Which was, finally, Perkus had to admit, not much. Sadie’s blunt remarks and frank unattractiveness seemed to permit, if not invite, unabashed inspection, and Perkus sometimes caught himself puzzling backward, attempting to visualize a woman onstage behind a drum kit at the Mudd Club. But that had been, as Sadie had pointed out, another time and place. For all her resonance with his lost world, she might as well have been some dusty LP from his apartment, one that he rarely, if ever, played anymore. If Perkus wanted to reenter his human life, Sadie wasn’t the ticket. Anyway, this was Ava’s apartment. They were only guests.

“Yeah, on and off for a couple of days now.” The dog had been hiccing and gulping between breaths as she fell asleep in Perkus’s arms or as she strained her leash toward the next street corner. Sometimes she had to pause in her snorting consumption of the pounds of kibble that kept her sinewy machine running, and once she’d had to cough back a gobbet of bagel and lox that Perkus had tossed her. That instance had seemed to puzzle the pit bull, but otherwise she shrugged off a bout of hiccups as joyfully as she did her calamitous asymmetry.

“The quick brown dog jumps over the lazy fox.”

“Other day I noticed you guys crossing Seventy-ninth Street,” Sadie said. On the table between them she scored with a pair of queens. “Thought you never went that far uptown. Weren’t there some people you didn’t want to run into?”

He regarded her squarely, playing an ace and advancing his peg before shrugging in reply to her question. “We go where she drags us,” he said. “Lately, uptown.” This left out only the entire truth: that at the instant of his foolish pronouncement a week ago, enunciating the wish to avoid those friends who’d defined the period of his life just previous, he’d felt himself silently but unmistakably reverse the decision. He found himself suddenly curious about his old apartment; he missed his treasure, his time machine assembled from text and grooved vinyl and magnetic tape. He even, if he admitted it, pined for his friends. Without Perkus choosing it, at first without his noticing, the dog had been making him ready for the world again.

So he’d been piloting Ava, rudder driving sails for once, uptown along First Avenue to have a look in the window of the diner called Gracie Mews. He was searching for his friend the retired actor, regular breakfast companion of Perkus’s previous existence, the one with whom he’d sorted through the morning paper—Perkus even missed the Times, he was appalled to admit—and marvelled at the manifold shames of the twenty-first century. Of all his friends, the actor was the most forgivable, the least culpable in Manhattan’s selling out. He was an actor, after all, a player in scripts that he didn’t write himself. As was Perkus, if he was honest.

The hiccupping dog could tell soon enough that they were on a mission, and pushed her nose to the Mews’s window, too, looking for she knew not what, leaving nose doodles, like slug trails, that frosted in the cold. It turned out that it was possible to wish to become a dog only exactly up to that point where it became completely impossible. Ironically, he was embarrassed to admit to Sadie Zapping, who was a human being, that he wished to be human again. With Ava, he felt no shame. That was her permanent beauty.

| 2009 |