CHAPTER 6

PREPARATIONS

I know damn well that if there had been a way to get to success without traveling through disaster someone would have already done it and thus rendered the experiments unnecessary, but there’s still no journal where I can tell the story of how my science is done with both the heart and the hands.

—Hope Jahren, Lab Girl

After the three-and-a-half-hour interrogation of the preliminary exam, my advising committee deemed me worthy to continue in my quest for science. I smiled weakly through the fog of blissful exhaustion that had descended upon my brain, and each committee member shook my pale, perspiring hand in congratulations on his way out of the conference room. I now had permission to set up the Hunley tests, and a budget of $4,000 metaphorically clenched in my tight, sweaty fist.

Early the next morning I slowed my car to a crunchy halt in the grass-overgrown gravel outside our lab’s test building, a place we lovingly called the Farm, with a capital F. Duke had given my adviser this white concrete structure, buried deep in the woods down a winding dirt road beyond an unmarked barbed-wire fence, largely because nobody else had wanted it. The students of our lab spent years gradually reclaiming the building from the forest, uprooting small trees from the gutters and evicting the intrepid rodents that had rampaged freely through the facility. We slowly made it our own: a working lab space, with no climate control, but with enough solitude that our massive shock tubes could tremble the walls without risking complaints from neighbors. The impressive main blast room hid inside the ramshackle building like a Corvette engine inside a rusted-out old Hyundai.

Dale had given me permission to open and claim two large, previously unoccupied cinder-block rooms. The rooms were currently used as storage, and were filled with pieces of old experimental setups hurled into haphazard heaps. One room was ringed by brown, dented metal benches, and the concrete floors featured a Tetris pattern of dingy, broken linoleum squares. The two rooms were connected to each other by a closet-sized steel passageway with a heavy metal door on either end, a creepy feature that had originally been installed for some past, forgotten generation of researchers to wash large pieces of equipment. Industrial-sized drains were dug into the floor outside both doors of this wash closet, perfect for either a serial killer or an underwater blast researcher who was about to make a mess.

The test space needed a water tank. The Farm was fully outfitted for blast tests in air, but we had no facilities for blasting in water. I needed something that was cheap, easy to modify, and common enough that I could easily replace it if I accidentally smashed it to smithereens with a shock wave.

I found a beauty in a For Sale post on the internet, a post whose text showed that the water tank’s current owner did not fully appreciate the scientific potential of his neglected treasure. She cost $60, a steal for such a gorgeous hunk of heavy-duty plastic reinforced with metal bars. She had originally been used for shipping liquids and grains, and now she slumped lonely and unloved in a heap of similar tanks on a farm outside Durham. Our lab tech, Jason, and I soon found ourselves in his truck, on a mission to collect my prize.

Setting up a blast trial can be an exercise in learning how to improvise a believable story. Like with home repairs, no first day of testing ever goes exactly according to the original plan, and trips to the hardware store to concoct a Plan B are virtually guaranteed. Helpful and inquisitive store employees become human-sized obstacles that I have to dodge like traffic cones, because in their kind dedication to their jobs they feel the overwhelming need to confirm that I am in fact buying the correct products for my mission. I can’t tell them the honest truth: “It’s part of my experimental test setup to blow stuff up,” because I don’t feel like cashing out my bank account for bail money.

During one trip I bought a massively atypical amount of pipe insulation, long, black foam tubes designed to wrap around copper water pipes and help them transmit hot or cold water more efficiently. I needed the foam to wrap around my gauge wires, both to make them float and to shield them from the water. I had cleaned out all the boxes of stock for pipes with diameters between 0.5 inches and 1.5 inches, and I stood in the aisle staring at the empty cardboard containers, thinking about asking if there were more in the back storerooms. I awkwardly clutched the assorted soft, dark noodles in an untamed bundle in my arms.

Like clockwork, Greg the employee appeared by my side, a traffic cone materializing out of nowhere. His tidy salt-and-pepper hair and his meticulously knotted, clean apron gave him the appearance of a man with careful attention to detail. A man who was probably very experienced at completing precisely planned home repairs . . . and therefore a man who would ask me a lot of questions. I could feel his eyes running over my arm-spider of foam tubes, noting their varying dimensions.

“Can I ask what you’re working on?” he asked. “Looks like you’ve picked out a couple different sizes.” He continued to look at me, the kind curiosity in his eyes slowly converting to sadness as I stood with my mouth open, waiting for an answer to materialize in my brain. “Are you sure you know what size pipes you have at home?”

“I’m fine, I’m fine, I don’t need help,” I tried to reassure him, clutching at my noodles. “Do you have any more? I don’t care what diameter.”

Wrong answer. I had confirmed Greg’s worst fears: I had no idea what I was doing. I didn’t even know what diameter pipes I had at home! Several of the foam tubes tumbled out of my arms as Greg looked at me with the profound pity of someone unable to save a train rushing headlong toward a cliff, someone who was sure I was wasting my money and would be back at the store soon. He somberly helped me gather the tubes, one at a time placing them back on top of the pile still in my grasp. Greg reluctantly allowed me to proceed to the cash register.

By the time I drove with Jason to obtain the tank, I was tired, and I neglected to concoct a just-in-case tale during the drive. As Jason passed me the end of a ratchet strap and I tightened the precious water tank securely into the bed of his truck, the farmer asked the fatal question.

“So, what’re you gonna use it for anyway?” he drawled.

I froze. My brain decided to disappear on me. I told the truth.

“I’m going to take it back to the lab and blow shit up in it.”

The farmer looked up at me, a youngish city dweller in a grimy T-shirt standing in the bed of a borrowed truck, and not even a flicker of concern or judgment crossed his face after my openly suspicious response.

“Well, if you break it, I’ve got plenty more.” Then, the man invited me into his home to use the restroom before we headed back to Durham.

After Jason and I body-slammed the hefty vessel into place above the floor drains at the Farm, Henry the trusty undergrad got to work sawing off its roof while I heaved a garden hose around the side of the building to fill the plastic-and-metal beast with water. Henry and I carefully lowered in the new partial shock tube we had constructed, a stubby monstrosity made of over 40 pounds of steel. We took cover behind the heavy metal door of the wash closet, and then I selfishly insisted that I wanted to be the one to press the big red button.

A gush of high-pressure helium filled the space in the shock tube behind the sturdy Mylar membranes. POP. SPLASH. A dozen failed trials later, we had evolved our equipment into a working setup. We would use the shock tube to test each pressure gauge to exhaustion, until we knew their quirks like they were tiny members of our family. These pressure gauges were responsible for measuring our squiggly lines once we got to black powder test day; if they chose not to work properly, we would have no data, and therefore no proof.

The water tank was far too small to perform the actual tests, even though I planned to use a scale model. Blast problems can be scaled down in size, to a certain degree. While there is a lower limit, in general if the variables are altered correctly, scaling can be used to conduct experiments that are cheaper, easier, and just as informative as full-sized explosions.

Mathematician G. I. Taylor performed one of the most famous examples of blast scaling when he used photographs of the detonation of a nuclear bomb that were published in an article in LIFE magazine in 1947. Armed with only the photographs, a ruler, and a thorough knowledge of scaling, he calculated that the bombs had an explosive yield of 22 kilotons (22,000 tons) of TNT. The actual yield, which was highly classified information at the time, was an impressively close 20 kilotons.

I wanted to scale the Hunley problem down to one-sixth the size of the actual 40-foot-long submarine, which meant our model boat would be 6 feet and 8 inches long—this was the biggest size scale I could carry myself and fit in my sedan without having to rent a flatbed truck for each test day. I needed a water volume at least as large as a pond. Duke was not an option; Dale and I knew without even asking that the safety office would never allow live explosives on campus.

Imagine how quickly you hang up on a telemarketer. Now imagine that the unknown telemarketer is asking you, not for money, but instead for permission to come to your home and set off live explosives on your property. Finding a test site had become an exercise in humiliation. Call after call, my pleas were sometimes met with polite rejection, but more often they were met with immediate, outright laughter. The army, calling me back from Fort Bragg in North Carolina, had semi-mockingly suggested that I “go find where those MythBusters guys set off their charges instead.” If only I had my own TV show.

By this point in the testing, Nick and I had moved into a small apartment together. He got home from his twenty-four-hour shifts at about nine a.m., and on those days I would go into lab late so that he could tell me about his night over hot tea and scrambled eggs. Our narrow wooden porch overlooked the featureless pavement of the apartment complex parking lot, but we had outfitted it with cheap, comfortable, blue plastic patio chairs, and the routine of curling up in one and listening to him talk always sent me to work in a good mood.

“They talked about farm equipment most of the day,” he sleepily muttered while watching the tea swirl in his mug, “so I mostly just hung out quietly in between calls.” Many of Nick’s fellow firefighters were also farmers on their off days, so farms and farm equipment were frequent topics of conversation at the station. That day, though, Nick’s comment snagged on one of the problems churning away in my brain. My forkful of eggs froze on its way to my mouth.

“These farmers, Nick,” I began. He looked up at me questioningly. “Do any of them have water on their property?” Nick slowly set his mug down. He nodded. He already knew what I wanted.

“I’ll ask around.”

The Hunley herself was also something of an outcast. The fatal sinking in October 1863, the one that killed Horace Hunley, drew additional negative attention to the boat. The remains of Hunley and his crew had been “ghastly,” and “the blackened faces of all presented the expression of their despair and agony.” Feeling the painful effects of carbon dioxide in their last moments, the doomed crew had “contorted into all kinds of horrible attitudes.” Confederate general Beauregard wrote that he didn’t want the boat used again. Basically, he wanted her buried away as a failed experiment. The Hunley and her torpedo were as unwelcome as my scale model and me.

By then the bombardment of Charleston had also begun, with Union troops nightly lobbing shell after shell into the city and all surrounding forts. The area was no longer safe.

Diarist Edmund Ruffin had previously made it a point to visit the little torpedo boat regularly in Charleston. He was especially curious about her as a tool for breaking the blockade. But after the October sinking, the Hunley disappears from his entries until months later, after he hears of her victory. She had been moved somewhere else, tucked away from sight.

Bert Pitt thought I had built a full-sized submarine, and yet even with that misconception, he had still invited me out to talk about the project.

“How will you get any pieces of the sub back out of the pond?” he asked. “Because we like to fish in there.” His family and favored neighbors considered the pond a prime fishing hole.

Nick had valiantly lobbied at the fire stations on my behalf, and he had struck experimental-setup gold. Firefighter Michael Phillips was Bert Pitt’s son-in-law, and they all worked the family farm together: an isolated, expansive tobacco, cotton, and sweet potato farm that included a man-made pond. Bert, the family patriarch, asked me to drive out to talk before he agreed to the project. Understandably, he had some questions.

I arrived at the Pitt family home at a time I thought of as early but was apparently several hours into their average morning. The statuesque main house stood proudly at the end of a long lane bordered by the smaller homes of the other relatives who worked the family farm, including Phillips and his wife and young children. Climbing the front steps of the traditional, two-story wooden farmhouse, I knocked loudly on the edge of the screen door then stepped back onto the broad wraparound porch.

A woman with shoulder-length brown hair swung open the solid inner door and stood looking at me through the screen. I assumed she was Bert Pitt’s wife, but based on her facial expression and bathrobe I suspected that her husband had given her no warning whatsoever that someone was coming to visit.

“Hi! My name is Rachel Lance, I’m here to see Bert Pitt.” Her eyebrows flicked briefly but perceptibly downward. I was coming across as a solicitor! “He’s expecting me,” I gushed out, smiling as widely as I could in the hopes it would convey good intentions. “He asked me to come by to talk about a science project he might let me do in your pond.” Mrs. Gwen Pitt’s face opened into a warm, welcoming smile. She reached out a hand to push open the screen door, and graciously invited me inside with the immediate hospitality characteristic of the South . . . if you are not an uninvited salesperson at eight a.m.

“This is for you,” I said, shoving my arms forward to present her with a paper plate piled high with a heavy burden. It was my Grandma Lance’s recipe for Southern red velvet cake, carefully wrapped in foil to guard it during the hour-and-a-half car ride away from the urban island of Durham. I was hopeful that baked goods would help me create a positive first impression, especially since I had nothing else to offer in exchange for the massive favor I needed. With the cake and its piles of traditional boiled frosting chilling in the fridge, Gwen called Bert in from the fields.

He was an average height but atypically tan and lean, his appearance a marked contrast to the soft, pale shapes that most of us have assumed after years of working in offices. I knew he had grandchildren, but his age was impossible to determine visually; decades of nonstop physical activity on the farm meant he still moved smoothly and quickly, without the creaking caution that often sets into knees and backs with the inconvenience of age. Wearing a baseball cap that covered what seemed to be a full head of mostly sandy-brown hair, Bert sat next to me on a barstool at the white kitchen counter. We looked together at pictures of the Hunley on the smudged screen of my laptop as I explained the project. His many questions came out rapidly, and with the same molasses North Carolina accent I had grown up hearing from my father’s parents.

After he asked about the danger to the fish I happily clicked to the next slide and explained that I was using a scale model, not a full-sized 40-foot sub. I didn’t plan to sink her, but if something unexpected happened the carcass of the boat would be easy to retrieve with basic scuba equipment. And fish are surprisingly robust, because fish don’t have bubble-filled lungs to smash the traveling blast wave to a halt. Some fish have gas-filled swim bladders, but experiments driven by blast fear during the Cold War showed that these non-bubbly gas spaces are much more difficult to damage than human lungs. As long as the fish weren’t within a half meter of my charges, they might be annoyed, but they shouldn’t be harmed. Bert nodded briefly on hearing this, then gestured through the kitchen’s sliding door toward the silver pickup truck sitting outside the back of the house.

“Well,” he said, “let’s drive out there and see if the pond has got what you need.”

The moment Bert walked out of the kitchen, a thick-coated golden retriever adhered herself to his heels. The dog, whose name I learned was Dixie, clambered into the bed of the truck while her master walked to the driver’s-side door, in a routine they clearly performed many times a day. I hopped in the passenger’s seat, and Bert drove me down one of the red dirt roads crisscrossing between his fields, past the personal cemetery that housed generations of his family, including a few headstones for ancestors who had fought for the Confederacy.

The pond was beautiful, both traditionally and from a scientific perspective. Dug by people, it was free of detritus and major obstacles—no sunken trash for me to cut myself on, no huge rock formations to crash my model sub into, no weird bottom features to cause unusual reflections of the blast waveform. It was at least a quarter mile from the nearest electrical outlet, but I was an engineer, so I shrugged that problem off. I would figure out a power supply later.

“It’s all yours if you think it’ll work for what you need,” Bert said, watching me sidelong as I stood on the wooden pier, looking out over the water. I suppressed my joy into the gruff, emotionless male mode of communication in which I was most comfortable because of my lifetime as a tomboy. I offered my right hand for a firm shake.

“It’s perfect. Thank you.”

A few weeks later, Bert Pitt and Mike Phillips watched from metal folding chairs on their pier as I squirmed into a wetsuit and plunged into the murky water for the first time. I had badgered three friends from another lab to come help me in exchange for home-cooked fried chicken, and together they waded through the muck of the shoreline while I spent hours swimming back and forth along premeasured lines of string to gauge depths and characterize the bottom topography. As I had hoped, the smooth, shallow bottom of the pond matched the ocean floor at the scene of the Hunley’s original explosion. The pond was perfect.

Sometime before early 1864, a few short months before her final mission, the Hunley had also been tucked away in her suitable new location. She was safely lodged on Sullivan’s Island, a long, narrow stretch of land whose southernmost tip was the northern edge of the mouth of Charleston Harbor. The island contained mostly sand and military fortifications, and it was distant enough from downtown that it escaped the nightly bombardments. Because of the narrow, sandy nature of the island, it was relatively free of civilian buildings, and therefore had few prying civilian eyes.

About halfway down the length of the island was a narrow channel called Breach Inlet. The inlet funneled not just the tidal waters from behind the island but also the currents contributed by three rivers. This strong outgoing flow of water would vigorously push along any fish boat, helping spare the crew from some of the cranking. Even today, the inlet is known for its strong, outgoing flow of water during the ebb tide. “Breach is notorious for drownings and other crises spurred by its powerful currents,” wrote one Charleston newspaper recently. The inlet was also protected by Battery Marshall, an armed fortification positioned just next to the opening.

The Hunley wasn’t the only fish boat hoping to launch from Breach. By then, the Confederacy was hard at work building additional small vessels in the template of the David torpedo boat, which were also kept in the area. Diarist Edmund Ruffin frequently traveled specifically to see them, taking careful measurements and making illustrations in his notebook. The plan was for four or five of these vessels to attack one or several blockade ships in perfect synchrony, in one of the first submarine wolf packs.

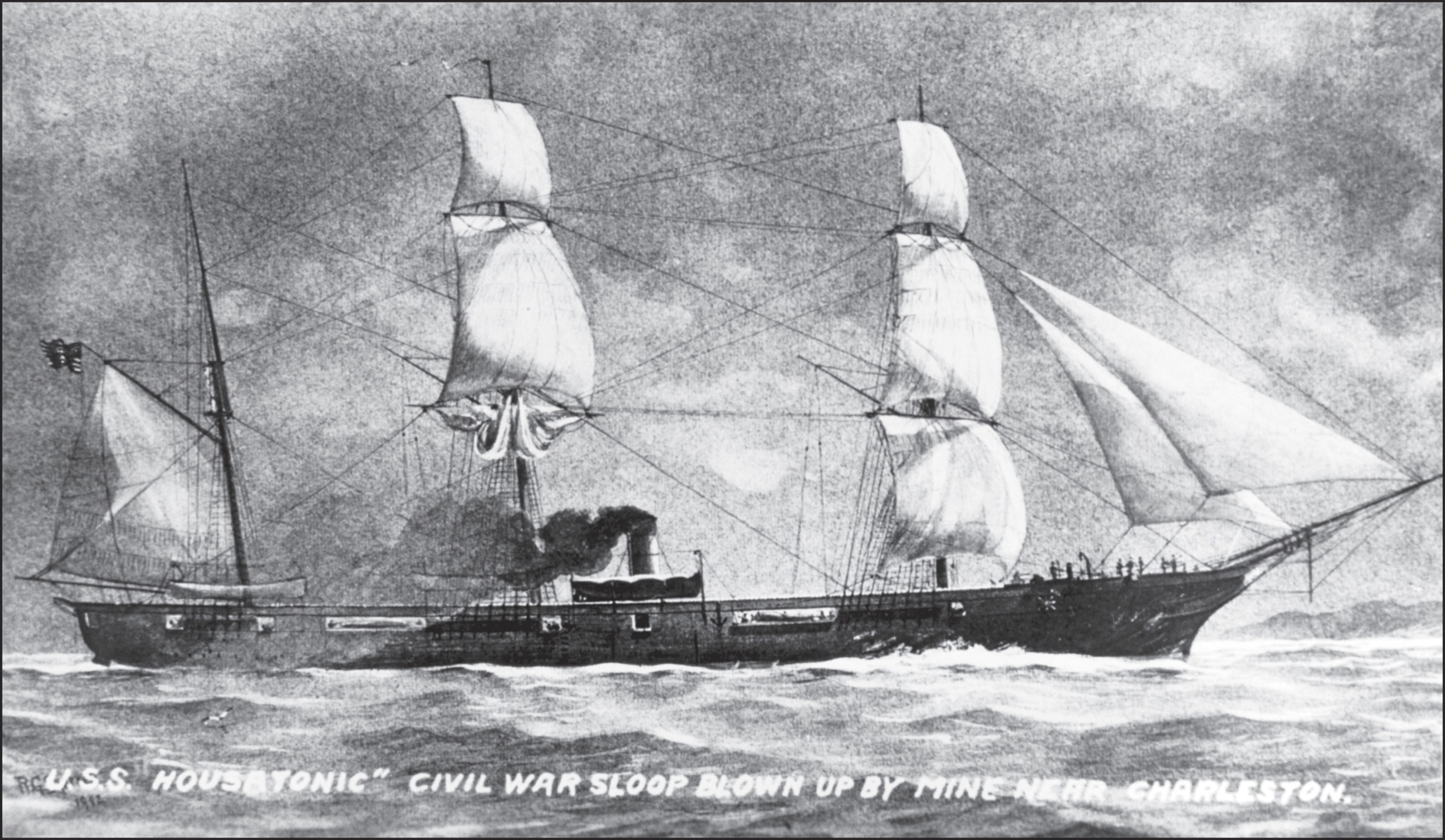

From their new location, the Hunley’s crew also finalized their perfect target. The Union knew to expect a submarine attack. The attack of the David and the information gleaned from spies meant that they were aware of the new technology, and some of the Union ships had taken preventative measures. They dropped nets and spars in the water to block torpedo-carrying boats from reaching their hulls, and set up more nets to trap them. The nets don’t seem to have actively foiled any attacks, but they were definitely a deterrent for the Confederate troops when trying to select a target. The Hunley would fare best against an unguarded ship, it was decided, and so the little submarine set her sights on the unguarded vessel closest to her departure point: the USS Housatonic.

Contemporary drawing of the USS Housatonic.

When Gabriel Rains churned out torpedoes for the defense of Charleston Harbor, he had at least one distinct advantage over me. Since torpedoes were new, there were basically no laws restricting their use. I, on the other hand, had a test site but would still apparently need a permit.

“Is this Rachel Lance?” the woman on the phone asked, a stressed note in her tone.

“Yes, this is she.”

She spoke assertively and rapidly. “You can’t set off black powder without a permit. You really need a permit.” I had left her a voicemail, and she had called me back almost before I had even put my phone down. “I’ll send you the forms.”

There had been some confusion about the amount of paperwork required to set off black powder, since it was a low explosive and therefore less fearsome than something like C4. I had been less than confident that there was a difference in the eyes of the law, and wanted to ask the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (the ATF) just in case. As it turns out, that was a good life choice. Dale was correct that we could buy all the black powder we wanted fairly easily, but only for use in rifles.

We sent in our application packet, listing Pitt Farm as our test site, and then we waited. According to the ATF, we should expect the permit process to take at least six months . . . six months before I could even buy the powder for the tests . . . six months of doldrums waiting to make experimental progress.

One day shortly afterward, Dale materialized in the frame of my office door. “JENNIFER LOPEZ IS ON THE PHONE!” He belted the words at me before pivoting on the squeaking rubber toe of his boot and darting rapidly back down the hall without further explanation. I swept up my keys, lab notebook, and a pen, and slammed the door shut in my rush to run after him.

J Lo was indeed on the phone, but this one worked for the ATF. She was calling about our permit application, and much sooner than anticipated. Dale and I swung ourselves hurriedly into chairs in his office as her voice began to pipe through his speaker phone.

“We were all very interested in your project,” she said, ambiguously. “Normally we process applications for big, ongoing projects like blasting open mines. Something this small is unusual.

“One of our agents is actually a history buff, and he’s offered to volunteer his help. He already has every permit imaginable, and he would come to all of your test days to help with the charges. That way you wouldn’t have to apply for a permit of your own. It would save you months of waiting and a lot of trouble.”

YES!

And that was how I first heard about Brad Wojtylak, the amazing explosives expert with the utterly unpronounceable last name.

A few weeks later, Brad himself walked into my office and sat in the old blue wheelie chair where Dale usually roosted. His job hunting drug dealers with the ATF took him all over the state of North Carolina, and he had paused on a trip zigzagging past Durham in his behemoth black work-issued pickup truck with a locking bed full of body armor. He was a former Marine who now sported a slight slouch from his time lurking undercover in the world of heroin, and he described himself as “a rare breed of ginger who can tan.” His cargo pants and T-shirt gave the impression of someone who valued function over frills. I liked him immediately.

The lab’s new medical student, Luke Stalcup, walked in and took the only remaining chair, the one shoved in the corner collecting dust. Luke was a former army explosive ordnance disposal operator, a specialty dedicated to safely defusing terrorist explosive devices and often referred to colloquially as “the bomb squad.” After his time in the military he came to Duke to learn how to continue saving lives with a scalpel instead. His ever-present rust-speckled facial scruff seemed like a minor rebellion against his former military life.

Duke’s medical school sends its students out into science labs for their third year of education, telling them they should somehow learn the extraordinarily complex field of experimental science in one measly year. Luke had chosen our lab because of his history working with explosives, and he had agreed to help me with my research if I agreed to help him with his. The start of the academic year meant undergrad Henry Warder’s time was nearly fully absorbed by his classwork, and I needed other assistance to conduct my experiments. I also lacked live explosives experience of my own, yet wanted to keep all of my fingers and toes, so I eagerly agreed to Luke’s deal.

The three of us sat in the narrow confines of my office. I had printed out oversized copies of the technical diagrams of the Hunley’s torpedo from the National Archives and spread them out on the desks. Luke picked up a dry-erase marker, spun toward the wall with the whiteboard, and began to sketch potential charge designs.

All three of us were avid scuba divers, with interests in underwater technology and physiology. All three of us were blast specialists, with different angles of expertise. We were ATF, EOD, and Duke. We were former Marine Corps, former Army, and Navy Civil Service. The three of us were the Hunley test team.

We had a test site. We had a permit. We had a place to test our gauges. We had the expertise. But we still needed a boat. I needed to find someone who could make me a flawless steel cylinder.

The first thing I noticed about the metalworking artist Tripp Jarvis was his hands. Manicures and engineering work make awkward partners, so around women and some more fashionable men I often feel the need to hide my functional hands, with their calluses and hastily lopped, un-polished fingernails. But when I met Tripp, his sturdy fingers were as black as gangrene.

He held one soot-caked hand down over the high ledge of the loading dock, and when I grabbed it, he helped me heave myself up from the parking lot of the Liberty Arts Foundry. He wore square-rimmed glasses and had wispy, sandy-blond hair, both also made darker by the same black welding scuzz. At a later date, over Thai noodles, Tripp would laughingly tell me he had once been described as having “a heart of gold, but the physical essence of the dwarf Gimli, from Lord of the Rings.”

The Liberty Arts Foundry was a collection of local artists in Durham, with each artist claiming a workspace inside one shared massive, high-ceilinged warehouse. Beautiful, miscellaneous pieces of art lay visibly scattered just beyond the doors, but because the casting furnace and metalworking equipment had heated the inside to a scorching temperature, Tripp invited me to take a seat outside. We each scooted a chair up to a round metal table that was positioned beneath a monolithic piece of art made of stacked steel geometric shapes. When I admired the sculpture’s smooth, uniform welds, Tripp told me it was his. The physical work of welding and hammering to create clean geometries was a kind of mental therapy for him, a therapy he had begun sharing by organizing art programs for veterans. I glanced back at him with new confidence. If he made this sculpture, then making me a simple tapered tube should be no problem.

I had used my computer rendering of the Hunley to create technical engineering drawings on extra-large paper, complete with dimensions and tolerances. I edged my chair closer to Tripp, spread the papers on the table, and began to explain the project.

The submarine would be round in the center so it could be rolled out of one solid piece of mild steel 1⁄16 of an inch thick. The Hunley was not perfectly cylindrical but was close, so the shape was a reasonable approximation that would greatly simplify the construction. The original submarine was made out of wrought iron, but wrought iron is extremely hard to come by in the twenty-first century. I had selected mild steel instead because this type of comparatively malleable steel is similar to wrought iron in the material properties that govern how they physically respond to blast waves, such as impedance and modulus of elasticity.

The boat needed working ballast tanks. The water sloshing about in the ballast tanks, especially the one in the front, could potentially affect the way that the pressure entered into the vessel. However, I had concluded after some careful calculations that I could eliminate the ribs that were inside the crew compartment, instead making the boat one solid piece. In the pressure ranges of the Hunley’s blast, the ribs should not have any effect.

A series of exhaustively detailed publications by the brilliant blast physicist Michelle Hoo Fatt describes how cylinders respond to the pressures of explosions, and how their physical responses change when they have internal support structures made of ribs with different spacings. Using her work I had concluded that the Hunley would be below the exposure pressures where its ribs would affect the way the walls moved and changed in response to the blast. The ribs began to matter if the pressures were more extreme and caused permanent damage and deformations to the cylinder. However, the blast pressures from the black powder should be below that level, and the real Hunley confirmed the hypothesis because its walls showed no permanent deformation from its full-sized torpedo. Therefore, no ribs would be included in the model.

As I explained the design, Tripp listened, waiting patiently for me to stop talking with his eyes wide beneath his smudged lenses. His face was making the concerned expression I have learned means that people are trying to follow me, but that I have jumped too rapidly into an unfamiliar topic. He jabbed his right index finger onto one of the dimensions on the clean white paper, leaving a dark black smudge, then worriedly tried to brush the smudge away with the same hand, making the mark worse by dragging it across the page.

“So, this is the length of the boat?” he asked. “And you want it round in the middle? Is it more important that the welds look good, or that they be watertight?” He was always the artist.

“Watertight. It has to be absolutely watertight. I don’t care what they look like.” I pushed the drawings toward him. “These are for you to keep. They have all the dimensions you should need.”

“Yeah I can do that,” he said, looking at the figures, now understanding. He confidently picked up the sheets of paper that, because they were now his, he could more comfortably smudge with impunity. “Might take me a couple of months, I have some other work going on now too.” While he was working, I would spend my time testing my gauges.

By the middle of January, out at the Farm, I could barely feel the steel of the shock-tube driver in my frozen hands, but I knew it was slipping. My knuckles were engorged with fluid; I could only partially bend my fingers to grip the 40 pounds of metal. Repeatedly dunking my arms in the cold water of the test tank had caused my hands to swell in a cartoonish way. The Farm had no heat, and after a recent temperature drop in the weather, the test rooms and therefore the water of the tank had both settled to a constant 40 degrees Fahrenheit. All sensation in my hands had been reduced to a vague numbness and tingling, with occasional vicious spikes of pain. Luke and I had built ourselves an improvised “warming hutch” by duct-taping scavenged panels of pink wall insulation to the sides of the steel washroom next to our test tank, and with two space heaters running full throttle we could coax the tiny box up to 55 degrees.

After each shock-tube blast, one of us had to reach into the tank, plunging both arms fully into the chilled liquid, and pull the tube driver out. Luke and I took turns. Whoever retrieved the driver got to huddle momentarily in front of a space heater to warm their bare, dripping arms. The other person lugged the steel across the building to the pneumatically powered impact wrench, opened the driver, and exchanged the spent Mylar membranes for fresh ones.

For each test, the driver sat facing upward in the center of the tank. Every test used four gauges, one between the driver and each corner of the tank, the same distance apart in a four-pointed star. Because the test setup was symmetrical, each gauge should measure the same signal . . . if they measured signals at all.

I was ready to smash our gauges with a sledgehammer. We had started with hydrophones, little baby carrot–shaped devices coated in black rubber that were designed to measure sound underwater. They had, in this test, measured absolute gibberish, recording only signals that vibrated wildly, and boldly declaring pressures higher than what could be physically possible.

We had moved on to using fiber-optic gauges, thin blue plastic wires that measured pressure with light and could be surgically threaded inside the human body to measure the pressures inside veins and arteries. The fiber optics measured the first few milliseconds of the shock wave, then completely gave up, recording only a dead flatline for the rest of the signal.

Neither the hydrophones nor the fiber-optic gauges could hack it because neither could take data fast enough to come anywhere close to the sampling rate we needed, and as a result they were outputting garbage. The gauges our lab normally used in air would not work underwater because they were not waterproof. Luke and I next tried a specialty gauge, designed specially for measuring underwater explosions, and it too captured only a few accurate milliseconds before producing a chaotic zigzag that looked more like a mountain range than a shock wave.

One magic fiber-optic gauge worked—gauge number 8—and if it were connected to port number 4 and only port number 4, then it would produce a beautiful, clear graph of the shock wave. But one gauge was not enough; these tests were too important to rely on one magic gauge that worked for mysterious reasons. We were nearly out of ideas to try to get the gauges to work. Luke and I had been trapped at the Farm, testing them systematically, for weeks. Change out the membranes, dunk the driver, take shelter, push the button, grimace at the results, change the gauge setup, pull up the driver, towel the water off, repeat.

My swollen digits couldn’t hold the weight of the slick driver anymore, and it slipped out of my control. I clutched feebly at the steel bolts as it fell, and it hit the floor with a resounding clang that prompted Luke, still curled tightly in front of the heater in the other room, to yell to ask if I was OK. The driver had smashed into the ground within inches of my grasping hands, and as I positioned it back in the bitingly cold water for what felt like the millionth time, all I could think about was how a few broken bones might have been worth the pleasant warmth of a pile of hospital blankets and a tray full of Jell-O.

My struggles were nothing compared to the struggles of the Hunley’s crew. The crew was dependent on their own muscle power to crank the sub out to the Union blockade, and to help ensure success they practiced every day. In the middle of winter, they sat hunched in the cold, dark recesses of the submarine for at least two hours a day.

Ultimately, my gauge salvation came from the most likely, predictable source.

When I first began puttering around with DYSMAS, the navy’s hydrocode computer program I used to model the blast exposures of unprotected World War II sailors suffering in the water, a navy engineer named Greg Harris patiently answered every one of my questions about the code. Every time I lay awake at night obsessing over some arcane facet of underwater blast physics and I wanted to talk it through with someone, I would type up a lengthy nocturnal email to Greg Harris, and he would invariably send me a thoughtful and equally nerdily excited reply by the next afternoon. When I was searching for obscure, un-digitized reports on historical underwater experiments, he invited me up to the Naval Surface Warfare Center where he worked in Indian Head, Maryland, and kindly supplied me with sandwiches so I didn’t have to take breaks while I pillaged his towering stash of old blast documents. So, when I couldn’t get my gauges working, when I ran out of ideas completely, when I began daydreaming about how pleasant an injury might be if only to give me a break from the problem, I turned yet again to Greg Harris.

Greg has an imposing presence, both because of his actual size and because his resonant baritone voice somehow seems to take up physical space in a room. He is tall, with a full head of thick hair shot through with more than enough silver to provide him with the immediate credibility that gets assumed for all scientists nearing retirement. Greg is free with his professional opinions and he will tell you the facts of physics immediately and clearly, and often accompanied by a cell-phone photo of the mosh pit at the most recent rock concert he attended. Greg Harris is an underwater blast expert, working for the same patriotic team that is the US Navy, but with a focus on undersea weapons design and damage to inanimate targets instead of damage or injuries to people.

“Sit tight,” Greg replied promptly to my emails of gauge distress. “I’m going to connect you with Kent Rye. He’s the navy’s gauge guru.”

Kent and Greg not only had a long-standing collaboration based on a mutual love of the explosion business, but Kent soon proved to be equally as magnanimous, endlessly ping-ponging ideas and theories back and forth with me as we reworked every aspect of my tank setup.

Greg invited me to see their pressure gauges working in action in a live-charge test. I basically drooled on my keyboard at the opportunity; I wanted so badly to learn more about the way other naval researchers were setting up their underwater experiments, to make sure I was getting every detail correct the first time rather than waste days, weeks, or months refining my processes. Greg knew I was interested in the Hunley, so he invited me up for the black powder tests he was about to conduct. His goal was to examine the in-water pressures output by a full Hunley-sized black powder charge. He was conducting the tests as part of a group that was intrigued by the same mystery I was, but they were investigating a completely different theory to explain her sinking. My manager in Panama City gave the visit the thumbs-up, the proper authorities rubber-stamped the official approvals to visit Greg’s test site at Aberdeen in Maryland, and I packed my car for the road trip up to underwater blast mecca.

The day of testing went mildly awry, as testing often does, but with profoundly inconvenient timing. The harness to hold the gauges broke on the first day and could not be fixed immediately, so I did not get to watch a single explosion. But I did get the opportunity to talk all day about the US Navy’s custom-made blast gauges and how they were used.

They were tested by tapping with a pen because the touch of a human finger can induce electrical signals that will create a false temporary pressure readout. The tiny, polished ball of tourmaline crystal inside will flex and compress in response to the pressures of the blast, creating electrical signals through the it’s-not-witchcraft-it’s-science of piezoelectricity.

Finally, while standing huddled on the shore of the Aberdeen site and looking out over the cold winter water, we collectively concluded that the fundamental problem was not my test setup. My test setup was correct. The problem was that I was working with gauges that simply weren’t capable of doing what I needed them to do.

Everything looked so easy at Aberdeen. When something needed attention in the middle of the pond, they took a small boat out; they didn’t have to swim. They had a full lab, complete with a roof to protect them from the weather, right next to the water. They had electricity. I was deeply jealous. My pond site was much lower-cost—it was free—but it was not nearly so luxurious.

After I returned home, Kent Rye mailed me pressure gauges. Two tiny, clear tubes with round silver balls suspended inside by wires, squeezed lovingly between sheets of soft, black foam packaged inside a stiff cardboard box that could have held an expensive bracelet. The gauges were handmade by Kent and the blast specialists at the Carderock, Maryland, navy base (officially called NSWC Carderock Division), and Kent considered them mutual US Navy property. He was willing to send them to me as a courtesy, since I was another naval employee working in a similar research area.

I slid the gauges down the dark-green high-strength fishing line I had installed in my water tank to mark the four carefully measured symmetrical locations around the shock tube. Magic fiber-optic gauge number 8 took a third spot. I bundled the red wires of the new navy gauges together carefully and routed them through the crack in the door of the washroom, where the sensitive recording electronics inside were protected from the spray from the tank. Luke pressed the big red button. POP. SPLASH. We jerked our heads toward the computer screen and psychically willed it to show us the curves. I held my breath as the signals processed.

All three gauges recorded the shock wave. Identical, beautiful waveforms. Sharp, infinite rises, straight up to the maximum pressure. Almost the exact same value for the peak pressure. (Some variation is inevitable.) Smooth, continuous slope back down. Magnificent.

It was time to build live charges. The in-water gauges were measuring the pressure waves properly and consistently. The gauges that would go inside the sub were air gauges that had been used successfully by students in our lab for years. I had installed them inside a small metal tub and blasted the tub in the tank to check, and they were perfect as usual. Tripp was done with the boat, and I had proved it was watertight by floating it in the chilly community swimming pool of my apartment complex even though the pool was still technically closed for the winter, with the staff watching apprehensively from the main office windows.

The charges were the only puzzle piece left before we could trek out to Pitt Farm and blast. Luke and I drained the test tank and turned our attention to making casings.

The design of our charges would parallel the design of the Hunley’s torpedo as closely as possible, but with a little help from modern technology. The 1864 Hunley team had used a plunger rod that sprang backward to hit a little nugget of highly impact-sensitive mercury fulminate. The design was effective, but dangerous. A small jostle could prematurely set off the charge. We would replace the unstable contraption with a squib—a small capsule that provides a tiny “match strike” starter explosion when you apply the right voltage.

The most common torpedo design used by the Confederacy during the Civil War was Singer’s torpedo. Not surprisingly then, the writing on the drawings from the National Archives states that the torpedo used in the attack was a Singer’s. However, the trigger used in the Singer’s design was actually a spring-loaded plunger device that was positioned completely externally to the body of the torpedo. The technical diagram in the National Archives drawing shows an internal plunger mechanism.

Torpedo legend Gabriel Rains was in Charleston during or just after the sinking that killed Horace Hunley, as in his records he wrote that “the boat was brought to the wharf & left for a long time where we were preparing torpedoes, but on account of the mishaps, I would have nothing to do with her.”

Rains also wrote that his compatriot Capt. M. Martin Gray was in charge of “making & managing” the torpedo used for the attack on the Housatonic. Rains’s records contain a technical drawing of the pressure trigger designed by Gray, and this trigger is mechanistically consistent with the trigger in the National Archives drawing. The trigger has a plunger that protrudes slightly externally, but otherwise is mostly internal, and the plunger is held in place by a retaining wire with a spring to launch it backward into a mercury-fulminate cap.

It therefore seems likely that the design in the National Archives drawing is generally accurate in its description of the charge configuration, but that it may have been incorrectly labeled as a Singer’s torpedo.

Luke and I hammered and shaped glossy sheets of copper into cylindrical tubes. We sealed the seams.* We stood looking proudly at our small army of shiny orange tubes, each standing on its end in a geometric battalion covering the battered metal lab benches. They needed only black powder.

I was trying to meet Brad Wojtylak to obtain free black powder, donated to the project courtesy of one of his ATF coworkers. My parents drove down from Michigan allegedly to visit Nick and me, but really because they wanted to watch some explosions, and I made the mistake of mentioning to them that I was meeting Brad vaguely near a doughnut shop. My father then became rather insistent about the doughnuts.

Brad’s text messages to me had contained normal English phrases the day before, but as they crossed into the morning, the communications had become more and more abbreviated. He was following a suspected drug dealer, tracking some kind of remote signal, and the nocturnal gentleman was unknowingly dragging Brad on an all-night, cross-state road trip. The doughnut shop was just off the highway he was traversing. As my parents and Nick ate their frosted sugar bombs, I heard the aggressively throaty rumble of Brad’s high-powered work truck pull into the parking lot, and I grabbed a cruller in a napkin before heading out to meet him.

“What is that, some kind of cop joke?” he protested as he stepped out of the cab and saw me holding the doughnut.

“No, I’ve just seen how you eat,” I quipped back at him. He chuckled and walked around the back of his truck to unlock the bed, then he reached inside to open the separate lock on a sturdy, ruggedized box. With his head buried under the lifted bed cover, he began to rummage with his right hand, and he handed me the first bag of black powder with his left.

I stood awkwardly, cruller in one hand, big pink static-free bag in the other. The sloppy grease-pencil handwriting on the bag loudly and proudly declared that it contained black powder, and since the bag was transparent it was clearly an unreasonably large quantity. As Brad nonchalantly handed me a second pink bag, I shifted my feet and awkwardly looked around to see if anyone was watching us.

“Uh, Brad?”

“Yeah,” he responded.

“What do I do if I get pulled over with this stuff?”

“It’ll be fine. Just have them call me.” He glanced up at me with bleary, pink-rimmed eyes, his fatigue thinly veiling his confusion over my concern. Having a badge must make it easier to explain things to people, I thought. “Maybe put it in the trunk,” he conceded as he handed me a third bag full of explosive material.

Brad, Luke, and I stood in front of the row of copper tubes lined up on the metal lab benches that ringed our room at the Farm. We were tethered to the bench by springlike yellow bracelets to prevent static electricity; the thin wires running through them kept us constantly at the same electrical potential as the metal table. Luke had also powered off the two dehumidifiers that normally ran nonstop. Without a centralized heating system, the palpable atmospheric sweat that defines the moist climate of the Deep South had rapidly oozed in through every pore in the walls to bring the indoor humidity up to a clammy 80 percent. We were not risking any miniature static-electricity lightning bolts jumping between us and the table to ignite the stray powder dust and granules.

Luke looked at me and rolled his eyes with a mocking smile. Brad was bent over the table, intently focused on the digital readout of the scale as he slowly, meticulously filled his copper cylinder, dropping in one single, tiny grain of powder at a time.

“Hey, Brad, it doesn’t have to be that exact,” I said, interrupting his laser focus. “Plus or minus a gram is fine. These little bombs aren’t that precise.”

“Hm, sorry,” he said, straightening back up and removing his tube from the scale so Luke could get started on his. “I’m too used to heroin. A gram is like $200. Those guys are really precise in their measurements. Oh, and Rachel?”

“Yeah?” I was already watching Luke zero the scale to fill his charge.

“Stop calling them bombs. These are pretty weak, so we want to avoid calling them bombs if we can. That word carries some specific meanings it would be better to avoid.”

I looked back at him. “OK. So what do we call them instead?”

Luke, already hunched over the scale, spoke up without shifting his eyes. “Science tubes,” he responded. Our first round of science tubes was completed by the end of the day.

I spent the night before the testing lying wide-awake, staring nervously at the ceiling. I was still wide-awake early the next morning when my alarm clock sounded. We formed a caravan out to the Pitt Farm test site, with each car responsible for transporting one key element of the setup. Brad and Luke carried the squibs and the science tubes, kept carefully separate from each other. I carried the submarine and the data-acquisition equipment. Altogether, it was over 250 kilograms of gear.

Everyone had been assigned jobs in advance. We had practiced carefully for this day. Brad and Luke began assembling charges while I secured the gauges inside the boat. My dad trudged to the opposite side of the pond to sink into a lawn chair in the mud, ready to help pull the submarine out to the center of the water. My mother, unsure she wanted the responsibility of helping with the science, was in charge of photography and snacks.

By the time we got everything set up it was midmorning. The atmosphere among the people on land, in the thick green grass and the pleasant sunshine, was like a carnival. The pond had a broad shore, a wide circumference of closely trimmed field that eventually transitioned to expansive stretches of crops on three sides and dense North Carolina oak forest on the fourth. All our cars were parked at random angles on the grass, and we had scattered mismatched camping chairs between them. An exposed wooden pier stretched toward the center of the pond, with a bench at the end for weary fishermen, and the entire extended Pitt family had congregated by it to watch our blasts. While I tightened nuts and bolts, Nick tossed an orange foam football with the two young Phillips boys, Bert Pitt’s grandsons, Mason and Austin.

Finally, we were ready. Crouched on the sun-bleached wood planks, I flicked the navy gauges with a pen, as I had been taught. They were working perfectly. Luke thwacked the bow of the submarine with a rubber mallet, and I watched as the gauges inside flickered to report the subtle resultant pressure wave. Brad handed Luke the first powder-filled copper tube. Luke and I attached the charge to the spar on the bow of the model sub, running the wires for the squib back to Brad’s detonator equipment on the shore.

I sat at the end of the pier, huddled with my hat covering the screen of the laptop so I could read it in the sun. I flicked obsessively between the various screens for the gauges, trying to quiet the booming, insistent voice in my head that was terrified I had missed something critical. The equipment was set to auto-trigger, meaning that as soon as the in-water gauges read a pressure above a few kilopascals, the computer would automatically record the signal, back-dating it a fraction of a second to ensure it processed the entire waveform.

I held up a hand to show Brad I was ready. He counted down, letting the small children push the two buttons on the detonator box. Mason held down one button during the countdown as Brad guided Austin’s hand to press the second button at the correct time. The charge went off.

When an underwater charge explodes, you see the explosion first and you feel it second, all well before you hear it. Light travels fastest, followed by sound in water, so the image of the plume and the sensation of the blast, having traveled through the water, into the ground, then up into your feet, both reach your brain before the kaboom can plod to you through the air.

This kaboom was small. It was too small, and the plume of water matched the sound in its unimpressive size. The gentle hum of the recording equipment told me that as it sat next to me, not processing data, instead still patiently waiting for the trigger. It had never received the signal to stop recording, and it was still waiting to feel some kind of pressure wave move through the gauges. Brad and Luke joined me at the end of the pier, and we sat staring at the heavy yellow box that was generating squiggly lines on the laptop screen. They were just noise, no blast waveforms.

We pulled the submarine back to shore and rechecked the gauges; they were all still working. Luke attached a new charge to the spar, and my dad pulled the submarine back out into the pond. Again, countdown. Two buttons. Kaboom. Again, too small. Again, the yellow box sat whirring, unperturbed, not having witnessed any pressure wave.

We tried a third time, but this time I switched the settings on the acquisition box and triggered the recording by hand. I zoomed in on the screen, staring intently at the recorded waveform, and finally saw a blip. A minuscule waveform at the time we had hit the button, but with a peak too diminutive even to reach the small pressure level required to trigger the box on automatic mode. A peak far too small for an explosive this size. Our baseball-sized charges were barely creating pressure waves.

Something had gone terribly wrong. A part of the experimental setup had failed. Or possibly many parts? There were about four hundred possible causes for this indeterminate catastrophe. I would have to pick through them one at a time.