CHAPTER 10

THE BLAST

One submariner compared the shock wave from a depth charge to tons of gravel being thrown against the hull. Another described the experience as like being in a garbage can while it was beaten with a club.

—Michael Sturma, The USS Flier: Death and Survival on a World War II Submarine

Confederate troops on watch patrolled Battery Marshall on the clear February night of the Hunley’s attack. The battery was an armed fortification on the sandy beaches near the mouth of Charleston Harbor, and it was positioned next to the narrow break in the land that the Hunley used as her gateway to the Atlantic. Each time the submarine journeyed out to sea she would thread the waters of this slim inlet, silently passing the soldiers and artillery on shore. Lt. Col. O. M. Dantzler, stationed at Marshall, was well aware of the departing submarine and her ambitious clandestine mission. Late on the night of the seventeenth, he waited in vain for her return.

Two days later, in a letter informing his superiors that she never came back, Dantzler left behind words that have been parsed and analyzed ever since. Words that, like Robert Flemming’s intriguing testimony, could be construed as a record of the fabled blue-light signal for victory.

“The signals agreed upon to be given in case the boat wished a light to be exposed at this post as a guide for its return were observed and answered,” he wrote. Some modern researchers have interpreted the letter to mean that he saw a blue light on the water after the attack, the signal the crew had planned to use to announce their victory. However, standing at Battery Marshall and spotting a small light near the wreck site of the Housatonic, 4 miles away, over twice the length of the Golden Gate Bridge, would have been challenging at best.

Even mammoth objects seem to shrink as they recede into the distance. However, the appearance and visual obviousness of a distant object, like a submarine, can still be described with a little bit of basic geometry. If the world around someone’s head forms a full 360-degree circle, each object within that circle occupies a certain fraction of that 360 degrees. The size of the object, as seen by a person at a known distance, can therefore be described in degrees, described by the portion of their visual world that the thing fills.

The moon, for example, takes up 0.52 degrees, just a hair over one-half of 1 degree in the circle. The 40-foot-long Hunley, if viewed perfectly broadside from a distance of 4 miles, would occupy only 0.10 degrees. Therefore, as Dantzler stood at Battery Marshall, staring out over the torpedo-filled Atlantic with the nearly full moon glowing down at him, the entire length of the dark Hunley would have appeared—at most, if she were perfectly broadside—to be about one-fifth the width of the moon rising above the horizon that he watched. Additionally, only a sliver of the vessel stuck up out of the water, about 2 feet in height, making her an even more difficult target to spot.

Standing at Battery Marshall and spotting the dark-hulled Hunley in the moonlit waters outside Charleston would have been mathematically equivalent to standing in the end zone of a football field and locating half of a standard drinking straw nestled in the grass 53 yards away . . . provided the shortened straw was grass-green, you didn’t know which yard line it was hidden at, and the experiment took place at night.

The Hunley was supposed to light a blue light, though, which should in theory make it more visible. Original recipes contained zinc to add the signature color, but by the Civil War the blue-tinged additions had been largely abandoned and the lights had been reduced back down to burning white balls of saltpeter and sulfur. It was a noticeable signal, but even these dynamic flares had a maximum size.

To an observer standing at a distance, a relatively large blue light will form a spot of brightness that appears at most about 3 meters wide. If lit at the site of the downed Housatonic, that 3 meters would have looked like only a pinpoint of white to the searching Dantzler. The light would have also been visually buried by the reflections and rustling waves dancing on the surface of the moonlit ocean. It would not have been easily spotted until the submarine cranked much closer to shore, which most researchers agree never occurred.

Dantzler never said that he saw the blue light that meant success. What he said was that he saw the signal that the Hunley’s crew wanted a guiding light that would help direct them in their return. He did not specify when he saw this signal, or of what form the signal took.

The Hunley’s crew may have signaled to the soldiers on shore as they cranked their vessel out to sea. They could have signaled on their way out of Breach Inlet as they passed the men at the battery, asking that a fire be lit later, after their planned explosion, to help them aim for the narrow passageway and home. The words Dantzler used are, unfortunately, unspecific.

No other witnesses from Marshall reported a blue-light victory signal. No records have ever been found indicating that the Confederate troops built a light or a fire for their submarine. A Charlestonian chronicler of the event would write down, albeit two years later: “The officer in command told Lt. Col. Dantzler when they bid each other good-by, that if he came off safe he would show two blue lights. The lights never appeared.”

The brutal reality is that math is more robust than words. Words can be imprecise. Words can be unclear and inaccurately interpreted, and it is common for them to change meaning and subtext based on the interpretations and the biases of the person reading them, especially when hundreds of years have passed since they were first written. Scholars have debated the nuances of texts from Confucius and Aristotle since they were penned millennia ago, and even the blue light itself was long mistakenly thought to be literally blue instead of white in color.

But math can tell only the bare truth. It can provide only the singular, inevitable conclusion that must be reached by the numbers. I finished my calculations of the blue light, of Dantzler’s view and how he would have had to spot the Hunley. For me, the math screamed its conclusion: I had no reason to believe that the Hunley’s crew survived their legendary victory.

Even with that information, the test team and I still had work to do. I needed more blast data before I could draw any positive conclusions. We had achieved a solid start using the shock tubes in the Duke pond, but we needed to repeat the feat with black powder, and then I needed to analyze the numbers. And finally, I needed to defend my dissertation and graduate.

Furthermore, I now had a new ticking clock looming over my head. ATF Brad, the extraordinarily helpful drug dealer–tracking explosives agent who had ensured I kept all my fingers thus far, was moving out of the state. He was being restationed, sent off to fight crime elsewhere in the country. He was set to leave in late August; I had to finish before then.

“The pond is open anytime,” Farmer Pitt told me when I asked about scheduling the next day out among his fields. “It’s yours whenever you need it.”

First, though, we had to get more explosive material. Brad called ahead for me so that I could legally buy it in bulk, giving the supplier some kind of secret ATF password that let me obtain the black powder equivalent of a family pack instead of scrounging for the plastic bottles one or two at a time.

Nick had the day off work and decided he was up for a lengthy drive to a mysterious munitions warehouse deep in the country. It seemed interesting, he said, and the warehouse did not disappoint. It was a nondescript complex of white, high-ceilinged buildings full of industrial shelving stocked to the brim with powder, ammunition, targets, and underground security boxes aimed at helping doomsday preppers bury and hide their gold and bullets. We carefully lodged 20 pounds of freshly purchased black powder in the trunk of my little blue Pontiac, the maximum amount permitted in one vehicle by law.

We were on the highway heading home when the car in front of us decided to start spinning in erratic circles, a crude high-speed parody of a human breakdancing routine. I never saw exactly what caused the accident. Something had sparked the small coupe two cars forward to hit the concrete barrier that divided our left-hand lane from the travelers heading westbound. The car had jumped back off with gusto and begun to turn doughnuts down the highway, catching the front end of the next vehicle in the line and forcing it to join the dance, metal and plastic and glass flying off like whirling shrapnel.

A moment before the chaos began, I had noticed the grille of a massive truck pressed nearly up against my rear windshield, and now my eyes were glued to the rearview mirror despite the rapidly shrinking distance between us and the melee ahead. Nick had the same thought I did, and he calmly but urgently spoke only two words while digging his fingers into the handle of the passenger-side door.

“BEHIND YOU.”

I could hear the tires of the truck behind me squealing; the driver had finally looked up and seen what was happening. I tempered my braking force based on how quickly he could stop, because I had already decided I would slam into the now-stationary cars in front of me before letting this truck hit my powder-filled rear end. My brain would provide me with only three pieces of information, shrieked rapidly and all at once:

Black powder is impact-sensitive.

Gabriel Rains said 25 pounds will blow the roof off a house.

We are a bomb.

My tires brought us to a heated stop what felt like mere millimeters from the crash, but in reality was probably several feet. The front end of the truck behind me consumed the entire view out my rear window. It was close enough that all I could see were headlights and the wide-eyed state of fear in the driver’s eyes. He should have been far more terrified, and he will never know.

The drivers of the formerly spinning cars climbed out and began to walk toward each other over the crunchy trail of plastic and glass. The driver of the front car waved and yelled something that sounded like “I’m so sorry.” They both seemed intact. Nick and I shared a moment of profanity, and then glared as the driver of the dark truck proceeded to pushily merge into another lane to continue his trip.

The rest of the trip home was blissfully uneventful.

Several days later, I drove cautiously over the rough, red dirt paths crisscrossing Pitt Farm for what I hoped would be the last time. The long, white shape of the CSS Tiny partially filled my sedan, pressed at one end into the outside lip of the trunk, with the bulk of her slim body stretched over the folded-down back row. Once I reached the quiet green shore of the little farm pond, I began to unload the myriad containers, toolboxes, generator, and data-acquisition components that were shoved in beside the tiny submarine. I heard the van of former army med student Luke Stalcup pull in behind me, followed shortly by the rumble of ATF Brad’s big black work truck.

We had split the blast equipment up, for safety. Brad had the powder, safe in a secure, reinforced explosives transport box. He climbed down from his driver-seat perch, lowered the tailgate, and began to build the charges on it. By now we were well rehearsed, and each of us knew our roles perfectly.

The Southern summer sun was blazing, and Brad was already sweating through the gray long-sleeved T-shirt he wore as a standard precaution to protect his skin from the dusty black powder. For a moment I watched him, with rivulets of perspiration running down his flushed face, perform cautious measurements of the shiny granules that would go in each charge. In stark contrast, I had shown up in a swimsuit, SPF rash guard, and giant sun hat. For once, I was feeling lucky to be the one whose job was getting in the pond.

It was just the three of us testing this time, plus Luke’s wife and their young child, who were prepared with a sun umbrella to sit and watch the blasts. Exhausted from the constant loading and unloading of the equipment, we had stripped down the experimental setup. Between the hard physical labor and the long workdays that somehow magically erased mealtimes off the clock, my weight had dropped 12 pounds during the previous months of testing. So this time, we left behind the high-speed cameras. We didn’t have any extra hands with us to operate them anyway. We also left behind the fiber-optic gauges, which only worked sometimes, maybe, if you told them the exact right compliments and said “please” in a soothing tone of voice, because their behemoth acquisition unit was hefty and only erratically coughed up useful data. It was just the three of us, the Tiny, the reliable navy gauges, and some black powder.

Crouching in the long grasses at the end of the pier, I tightened the small access panel that shielded the Tiny’s interior from splashing water. An omnidirectional navy gauge was sealed inside. Luke grabbed one of the metal rings protruding above her hull, and I grabbed another. Together we carried the small boat with her lead-covered belly through the mud that ringed the shoreline and set her down in the pond. As she bobbed slowly, I climbed back out to walk barefoot down the sun-warmed wood to the end of the pier, where our tidy pile of electronics was shielded by a big black shade tent. Luke picked up the trusty rubber mallet. When he struck the stern of the floating model, the squiggly digital line on my monitor jumped. The gauge inside was reading, and it was reading perfectly, from all directions.

Brad carried the first charge from his truck to the shore. It was a small contraption with a design that we had perfected and strengthened as much as we could within the permissions given us by the ATF. It was a slightly busted, fifth-owner, four-cylinder Mustang of a charge. Luke attached it to the bow of the boat, which hosted a threaded receptacle that could accept throwaway metal spars. The spar unearthed with the Hunley followed a subtly curved shape that implied it had been the recipient of a massive force, and some of our spars had also been similarly deformed by the stronger blasts.

As Luke pulled the Tiny into the center of the pond, I was struck once again by how smoothly and easily she glided. Her peaceful wedge barely disturbed the fluid, separating the water on either side with a grace that was jarringly inconsistent with the weapon of death she hid just below the surface. Long dreadlocks of black foam trailed out behind her, the insulation tubes that protected the gauges’ wires from the signal-leaching water.

I triple-checked the gauges’ signals on my screen and held up a hand to convey my readiness to Brad. He bellowed the countdown. He pushed the second button on the blast box to trigger. First, I saw the plume of the geyser of water, and then I felt the pier vibrate. Last of all, I heard the blast. As always.

Brad yelled from shore that he could feel that charge through the ground. What he meant was: This one was strong. Stronger than any of our previous tests with the boat. I may have grunted in acknowledgment, but I was too consumed by staring at the whirring laptop to respond in any meaningful way. I waited for the screen to display the pressure waves from the charge.

There they were. Both of them. The waveform from the explosion, in the water, with a quick rise that would kill even though it wasn’t technically a shock wave, followed by a lovely smooth decay. But even better, there was also a clean waveform from the internal pressure gauge: a squiggly line measuring the jagged, erratic scream of bouncing waves trapped inside the hull of the boat. A squiggly line that had sharp peaks, peaks with rapid rises, peaks that rose to maximum in under the 2-millisecond cutoff for blasts that would hurt human beings.

Before Luke and Brad could begin to set up the second charge, I tossed my hat down on the pier and plunged feetfirst into the warm brown water. It was deeper than before. The pond’s bottom now featured a smooth, round crater under the former site of the charge. Once again, I felt around blindly until my fingers contacted what they were groping for, and I pulled out the fragments of the charge casing. The pieces had still separated along the lines of construction between their various parts, so these blasts were still smaller than the one that would have been created by the welded-shut torpedo of the Hunley. But this time, the fragments showed that the black powder was reaching some degree of pressure buildup. The blasts were inarguably larger than they had been before.

We set off as many charges as we could before the sun began to set on the pond. Blast after blast, we captured and saved the waveforms. The readings looked blissfully consistent. And like the actual Hunley, the scale-model Tiny refused to show any damage herself, even after repeated blasts, even as she willingly transmitted the pressures inside.

By the end of that day, the data saved on the laptop was worth more to me than anything I owned. I immediately backed it up in triplicate.

When the sun began to drop in the sky and we were getting low on powder, we realized our testing was finally over. We had blown an additional meter and a half out of the bottom of the pond. But we had gotten what we needed. After cleaning up, I insisted on one final group photo with the Tiny. Luke’s wife, Alane, obliged, documenting our fatigued, filthy, sweaty, utterly depleted but nonetheless ecstatic faces with my camera. Brad was moving the following week.

The next step was to translate all the squiggly pressure traces into a meaningful description of what happened on that cold, dark night in February 1864. My end goal was not simply to sit in a series of muddy ponds and set off charges for fun. It was to determine, scientifically, whether the crew had been injured or killed by their own massive bomb.

Answering this main question required solving each of its three separate parts. Part one: How strong was the pressure wave in the water from the explosion? Part two: How much of that external pressure wave transmitted inside the boat? And finally, part three: Could the pressures inside the boat have killed the crew?

First, I wanted to tackle question number two on this scientific to-do list: How much of the blast’s pressure transmitted inside the submarine? This important question had been the goal of the months of muddy experimentation, after all. And now, with the testing complete, I could finally answer it. I could calculate what percentage of the blast pressures traveling through the water had worked their way inside the hull.

In an explosion, the behaviors of everyday objects can surprise us. Items in the path of the traveling blast wave are hit by that sudden, rapidly rising smack of pressure, which skyrockets from zero to maximum far quicker than any other forces these objects would experience on a normal day. As a result, sometimes even those items that we think of as solid, like steel walls, can ripple and contort like Jell-O for a fraction of a second. This bizarre behavior is what makes high-speed videos so fascinating, and it is also how the blast waves were more than likely getting inside the Tiny.

Imagine lying in the grass beneath a trampoline with your eyes closed. Someone climbs onto the stretchy black canvas and jumps. Even if trampoline springs were not infamous for shrieking loudly, you would still be able to tell when each jump occurred without hearing or seeing it. Every downward bounce of the black mat would be felt as a puff of air, a subtle and brief wind caused by the motion of the stretchy surface toward you, pushed downward as if the moving surface were an inefficiently designed fan. The larger the person or the higher the jump, the larger the motion of the trampoline, and the stronger the wind. If the person jumping is small, they get bounced back up without too much drama because they do not have enough momentum to cause a lasting deformation of the surface. But if the wave is more powerful, it is more like a sumo wrestler, with far more momentum. The materials tear, and the wrestler crashes through. Water gets in. The ship sinks.

The same effect occurs when a ship’s belly is hit by an underwater explosion. Analogies are never perfect; the reality has some additional complexities, but that’s the general idea. The traveling blast wave impacts the hull and for a fraction of a moment the material deforms. Even if the blast causes no permanent damage it will still cause the hull to flex and bend locally at the point of impact. When the hull flexes, it pushes a puff of air inside, just like the moving surface of the trampoline. This puff comes off the back face of the wall as a new, internal pressure wave.

Because I am a scientist—gravity is my favorite theory—here is the fine-print scientific disclaimer that my brain forces me to include: There are some other possible theories to explain the transmission that we measured. This one is just the most likely candidate, given the data that I have right now.

Before testing began, I tracked down the undergraduate student in the lab with the smallest hands, and at my request she reached her slender arm through the access hatch and up into the bow of the Tiny to attach a small rosette of strain gauges to the wall. These gauges would measure the amount of “flex” of the wall in response to each blast. And they worked! They showed the hull deforming at the exact time the blast waveforms hit the boat, every time. Unfortunately, the gauges were not positioned on the bottom of the model, where we eventually determined the blast was transmitting the most. As a result, the test team and I cannot say that we have proved exactly how the pressure was getting in. Rather, we have proved only that it was getting in somehow, and that parts of the hull were flexing.

However the pressure wave does get in, once it transmits it can then bounce around within the enclosed narrow walls and build upon itself. The entire goal of the experiments with the Tiny was to answer the second critical question, to measure what percentage of the blast wave in the water got passed through to the inside of the boat as this puff, and then hit the crew smack in their chests.

I needed to use knowledge from the decades of studies before mine to analyze the results from my own experiments. Luckily for me, a sunken ship is not very useful, and so with the goal of preserving their vessels, the naval community has studied underwater explosions for quite some time.

One of the first scientists to examine underwater blasts mathematically was G. I. Taylor, the same genius who calculated the atomic bomb’s highly classified yield using only photographs published in LIFE magazine. To study underwater explosions, he suspended steel plates of varying thicknesses in the ocean and blasted them with TNT, each time measuring the shock wave and noting its effect on the plates. His goal was to predict when World War II–era ships would be fractured and sunk by nearby underwater mines.

Modern scientists are still building upon Taylor’s pioneering work. Each new batch of math wizards slowly contributes their data to the puzzle in a multigenerational group effort to understand how surfaces respond when hit by an explosion.

The advent of computational modeling in the late 1970s changed the game monumentally. The ships and tanks and buildings could suddenly be built artificially, using thousands or millions of tiny data points inside a computer instead of investing the time and expense to make a physical model of each and every setup. Scientists looking to predict the destructive effects of nuclear explosions started plugging the complex equations into elaborate computer simulations, sipping coffee while the machines slogged through the heavy math. Thousands of computers now sit in hundreds of labs, chugging tirelessly through millions of equations without error, overnight and through the weekends.

In a twist of cosmic irony, the modeling work most relevant to the case of the Hunley was performed at Clemson University at the same time as, but totally independently from, the conservationists scraping away at concretion in another building. The engineers of the Grujicic Lab built digital slabs of material and calculated how those slabs would respond to shock waves. They used a well-established family tree of equations that traces all the way back through decades of scientific lineage, straight to Taylor himself.

But their model, for the very first time, also carefully examined what happened behind the material slabs. Previous papers by other researchers had casually observed that a secondary pressure wave propagated off the back face of the slabs, but they had mostly dismissed it as an interesting side note. The Grujicic Lab modeled it fully. They observed a shock traveling inward off the flexing face of the digital material wall. Their results supported the previously published physical data from a different lab that had measured exactly such a wave propagating inside the body of an armored vehicle. And because the Grujicic model was digital, they could manipulate the variables in multitudinous ways, fully characterize the wall’s behavior, and show that their results agreed with the rules and equations explored and outlined by previous researchers.

They still primarily dismissed this secondary shock wave as an interesting side note, just like the group that blasted the armored vehicles. And the fact that they did so was actually quite reasonable and understandable. The rates of transmission were so low that for most situations the secondary wave couldn’t be considered a realistic source of potential injury. The shock was interesting, but too minuscule to be harmful. Except, of course, in unusual circumstances that would maximize the exposure. Like if an extremely large bomb were positioned close to a thin-walled structure, such as a historic submarine. Perhaps while immersed in a medium, such as water, that would very efficiently conduct the blast waves toward that structure.

Compared to a normal shock wave, the slow-rising pressure waves created by black powder are the equivalent of the person on the trampoline slowing the speed of their jump. It’s as if they hit the trampoline with the same amount of force, but at a slow-motion rate of impact. This key difference makes it difficult to build a computational model to directly examine the effects on a structure from a nearby black powder explosion. Unfortunately, black powder is so profoundly obsolete that there are no published experiments in water—that I could find—to compare a model to. It would therefore be difficult to ensure that a computational model has been built correctly. In other words, the slow rise time tosses something of a wild card into the neat stack of calculations that are normally used to predict the damage from shock waves.

But still, Grujicic and Taylor and all those scientists between them had meticulously puzzled out many of those calculations for how material walls behave when smacked with a shock wave. Structures near a black powder explosion should still follow those same rules and patterns, the same laws of physics, but with the curves shifted because of the slow rise time of the powder. And because of our black powder experiments, our little team now had the data to evaluate how those curves shifted for the unique case of the HL Hunley. Together, their rules plus our experimental data could calculate how much pressure got inside the Hunley’s hull.

Once processed and plotted, our data turned out to create a stunning little curve, exactly as hoped. Even with the slow rise time of black powder, the measurements of transmission into the hull of the Tiny still fit the same smooth, arcing pattern of response as every blast experiment all the way back to Taylor. The curve had shifted, as expected, but it still fit the same rules, and now we had the data to support that assertion.

After some excited emailing back and forth, a friend in the same line of work stuck a gauge inside his underwater model during his next blast test. His structural model was different in form from the Tiny and his data point was in a different region of the curve, but nevertheless the single point he provided was neatly in line with the transmission predictions of the Tiny’s data. It was an external confirmation that came as a huge relief.

After all the heavy math, the final answer to the question was 8.4 percent. The pressure level inside the crew compartment of the Hunley would reach about 8.4 percent of the maximum pressure level of the portion of the blast waveform that slammed against her belly like thunder. At higher pressures, the percent transmitted of that higher pressure would also increase.

If the torpedo had been on an even, level line with the bottom of the hull, with the spar pointing forward rather than downward, almost none of the blast would have transmitted inside through the bow.*

Question number two was solved. Next, I had to figure out how much pressure was really sent out into the water by the Hunley’s massive, copper-encased, black powder torpedo.

Months earlier, I had discovered that the archives of the Hagley Museum were filled with endless stacks of lab notebooks about black powder. Most people in the 1800s resorted to rudimentary approaches for testing the strengths of their powder mixtures, building devices like small pendulums that could measure how far the force from the burning material pushed a swinging weight. But at the du Pont powder mills they insisted upon science, and they were able to generate actual numbers.

The pressure gauges of the time were small, crushable copper devices. There were a few different exact forms, but to measure a test, one of them was screwed into the body of a piece of heavy artillery. Experimenters would load the weapon with the powder to be tested, and fire it. Not only could they measure the distance the projectile traveled, but the little copper devices would deform proportionate to the amount of pressure inside the barrel. The amount of crush could be translated into a numerical measurement of pressure.

Some of those data points were from charges of 135 pounds of powder, just like the minimum size of the Hunley’s torpedo. According to the historic data, 135 pounds of Civil War–era black powder, when confined, can create 24,200 pounds per square inch inside the barrel, or 167,000 kilopascals. For reference, that is more than 151 “Rachels standing still” pressing on each and every square inch of the inside of the artillery.

Our charges’ construction materials would rupture and shatter at somewhere below their maximum possible internal pressure of 2,600 kilopascals, a number only one sixty-fourth the pressures generated by the du Ponts. Therefore, our little science tubes burst from internal pressures somewhere in the ballpark of a measly one sixty-fourth the internal pressure levels of a fully confined charge. The pressures our charges sent propagating out toward our small boat’s hull would have been similarly smaller.

I could also compare the pressures from my mini charges to the large-scale black powder tests conducted by my navy civil service colleagues. I had driven up to watch their actual blasts and been foiled by an ill-timed equipment failure, but the researchers were nonetheless generously willing to share their data. After some careful discussion, we agreed on the exact phrasing that would be used in my dissertation and in the final paper to publish the results. My supervisor from my base in Panama City* signed off on the sentence, and the Public Affairs Office approved it for public release.

“US Navy testing of a full-sized black powder charge designed to measure the output of the Hunley’s torpedo showed peak pressure values of approximately 7,600 kilopascals (1,100 psi) at a measurement location comparable to the keel of the Hunley.”

The full-sized charge had achieved pressure levels in the water, pressures that would hit along the bottom of the boat, forty-three times as high as mine, despite the fact that this charge was also constructed with limitations that potentially weakened its strength.

The data from the full-sized charge test and the historical data from Hagley told me that the pressures near the submarine’s hull in 1864 would have been—at least—in the range of forty-three to sixty-four times stronger than anything I had measured in the pond.

If the Hunley had a charge filled with 135 pounds of black powder, then she would have blasted toward herself a rapidly rising pressure waveform with a peak pressure of, at minimum, the pressure level measured during the full-sized US Navy test: 7,600 kilopascals.

Gabriel Rains cleverly deduced that lowering the torpedo would cause more damage to the enemy ship. So, the torpedo was lowered, inadvertently positioning it so that it would transmit even more of the blast into the Hunley. Pressure is technically omnidirectional, but for the type of “trampoline bounce” behavior in this case, the amount transmitted inside is affected by the angle of the blast, and can be calculated as if the pressure is acting at an angle. So, with the torpedo at an estimated downward angle of 11 degrees, the fraction of the 7,600-kilopascal traveling wave that hit the keel perpendicularly would have been 1,460 kilopascals, or about 1.3 Rachels per square inch.

The Tiny taught us that 8.4 percent of that peak external pressure would transmit inside the hull. So, using the number of 8.4 percent, the crew sitting at their stations would have been exposed to a minimum of 123 kilopascals of pressure jumping around inside the metal tube. And it would have taken the form of a long scream of a pressure wave, with rapid rise times.

I could now check questions one and two off my to-do list. I knew about how much pressure the charge should have produced, and about how much pressure made its way inside the hull. They were not exact numbers, but they were reasonable estimates of the minimum expected levels.

The only question remaining was whether a minimum of 123 kilopascals of pressure could kill. Luckily, that was the easy part, thanks to the mental giants who came before me.

In the field of injury biomechanics, it’s not considered very informative to label threats simply as “fatal” or “safe.” The reality is, people can have wildly different physical responses to the same accident. Millions of minor variations, such as body mass, physical fitness, genetics, and the exact position at the time of the event create a spectrum of possible injuries that can result from the same situation. If 100 identical cars traveling at the same speed all crash into 100 identical trees, some of the drivers will walk away while others will not survive. The most useful prediction that we can provide, as a field, is to give each person a percent chance of injury or death.

Blast trauma is no different. The predictive curves, called the “risk curves,” calculate the percent chance of injury or death from each explosion. The risk curves for blasts in air are the product of decades of hard labor by hundreds of scientists who laboriously collected and compiled more than 12,000 data points, painstakingly, one at a time. The most common current use for the curves is to help prevent injuries and fatalities to soldiers from IEDs.

At the minimum expected peak pressure of 123 kilopascals, each member of the Hunley’s crew would have had a 95 percent risk of immediate, severe pulmonary trauma. The kind that would leave them gasping for air, possibly coughing up blood, and most likely unable to crank. Each man would have also had a 20 percent risk of immediate fatality, of slumping over at his battle station without ever processing the realization of his victory. Because that probability applies to each man, it means that this scenario carries fifty-fifty odds that at least two crewmen dropped dead instantly. With a 95 percent chance of serious pulmonary injury, it seems improbable that any survivors could have done much to help bring the boat to shore. And those are the calculated odds using data from a 135-pound torpedo, tested in an experiment with a casing that was likely underconfined.

Since the case of the Hunley, no other submariners have been shown to have received such injuries, even though many other submarines have experienced underwater explosions. This conspicuous absence is because by the turn of the year 1900, submariners had already unwittingly protected themselves from blast transmission. They began designing their vessels to travel deeper and deeper beneath the surface of the waves, and as they did so they made the hulls of their vessels thicker and thicker. Serendipitously, these thicker hulls also reduced the ability of blast waves to force their way inside. Most submarines beginning around World War I also had two hulls: both an inner and an outer hull, which would have provided further protection. However, to keep the math simple, I will ignore the additionally protective effects of the outer hull.

The inner hull of a typical World War II submarine was shaped out of curved steel with a thickness of ⅞ of an inch, equal to 2.2 centimeters—which is over double the thickness of the Hunley’s. Most depth charges were made out of TNT, usually 300 pounds of TNT to be exact, and the submariners knew these bombs could split open their vessels anywhere inside a range of about 100 feet. Using the curves generated during the Tiny testing, a hull of this thickness exposed to a 300-pounds-of-TNT explosion that took place just a hair beyond the kill radius would result in a transmission of a measly 0.180 percent of the external pressures to the inside. That is only one forty-seventh of the percentage transmitting into the Hunley.

Inside a World War II submarine with its thickened hull, transmitting at a measly 0.180 percent, the pressure levels from an almost-ship-crunching explosion would be only 2.4 kilopascals. This value not only has zero chance of causing any injury or fatality, but it can actually be discussed in terms of sound. It is a pressure level equal to 161 decibels, which is about the same volume level as a nearby gunshot. World War II submariners described the sound of nearby depth charges as “deafening,” “abominable,” “ear-shattering,” and like “someone hitting the hull with a million sledgehammers.” A remarkably universal observation is that the barrages of underwater TNT would cause the onboard lightbulbs and other glass items to shatter, a phenomenon that is consistent with low levels of blast waves, which tend to make frangible glass objects their first victims. However, to the submariners, this explosion, even though it was only a tiny fraction of an inch away from crashing through their hull and sinking them, would nonetheless have a zero percent chance of causing injury.

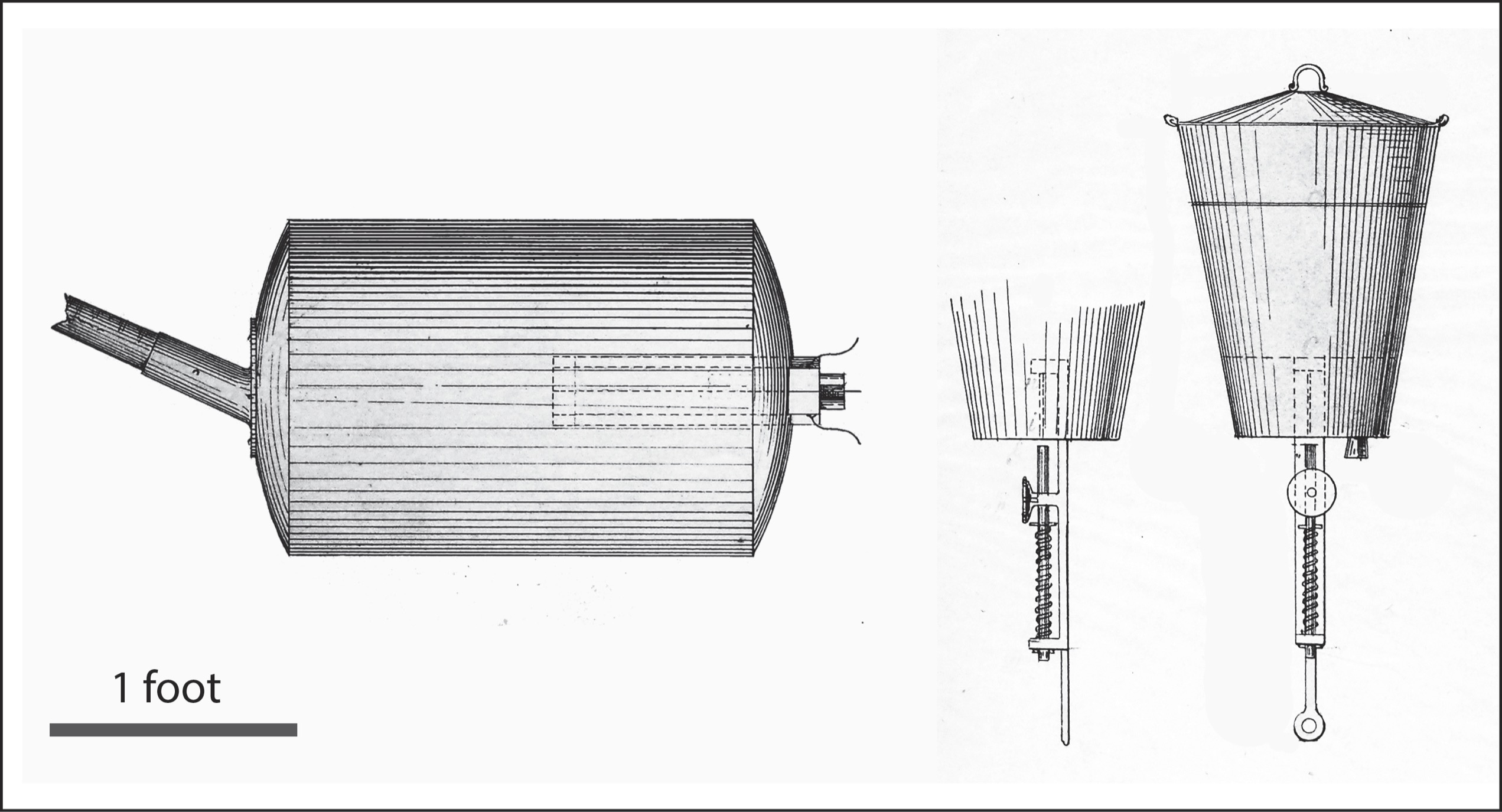

The charge weight of 135 pounds comes from a historical drawing that is nestled away in the US National Archives, in the papers and records of Union officer Quincy Adams Gillmore. General Gillmore was responsible for leading the assault on Charleston, although his ill health meant that he was more frequently absent from the city. The boxes of manila folders holding his papers include a full stack of drawings of Confederate torpedoes, obviously penned by an illustrator with technical expertise. Most of them are drawn to perfect scale, with the goal of documenting the variety of torpedo models that were found in Confederate hands.

The drawings of the torpedo supposedly belonging to the Hunley are extraordinary in their detail. A simple, handwritten label at the top of one illustration claims that this is the torpedo “used for blowing up the Housatonic.” However, no other supporting documentation is attached, and no other information about the torpedo or the attack is present anywhere in Gillmore’s files. The drawing floats alone, with absolutely no context besides being buried among other drawings of varied torpedoes.

There are two problems with this claim. First, the drawings are to perfect scale. Because the file folder is filled with miscellaneous Confederate weapons and designs, it seems as if the pile of illustrations was made after the fall of Charleston, long after the attack of the Hunley, once Gillmore’s staff entered the decimated city and obtained access to the Confederacy’s cache of remaining torpedoes. If so, the scale drawing therefore seems to have been made from a second torpedo, one that was declared by someone onsite to be sufficiently similar to the torpedo used by the Hunley to justify adding that note at the top.

Second, as previously mentioned, the illustration is labeled as a “Singer’s torpedo,” but it does not actually depict one. “Singer’s torpedo” was a specific, floating, tethered design commonly used by the Confederacy, and it both looked and functioned differently from the one in the drawing. Singer’s design was made of tin and had a trigger mechanism with an external spring and plunger, very different from the internal mechanism shown in the illustration.

A Union-compiled book now resting in the National Archives contains contemporary letters and drawings about Confederate torpedoes, and this book unwittingly contains several drawings of Singer’s design. None of them are correctly labeled as Singer’s torpedoes, indicating that the Union did not in fact know what that design looked like. The labeling discrepancy is therefore critical enough to raise this question: How reliable was this person who declared the two torpedoes were similar or the same?

A different, previously undiscussed historical record states that the “submerged and slumbering thunderbolt” was much larger. It states that the torpedoes being built for the Confederate fish boats were filled with 200 pounds of black powder, not 135. And that record comes with both context and established reliability.

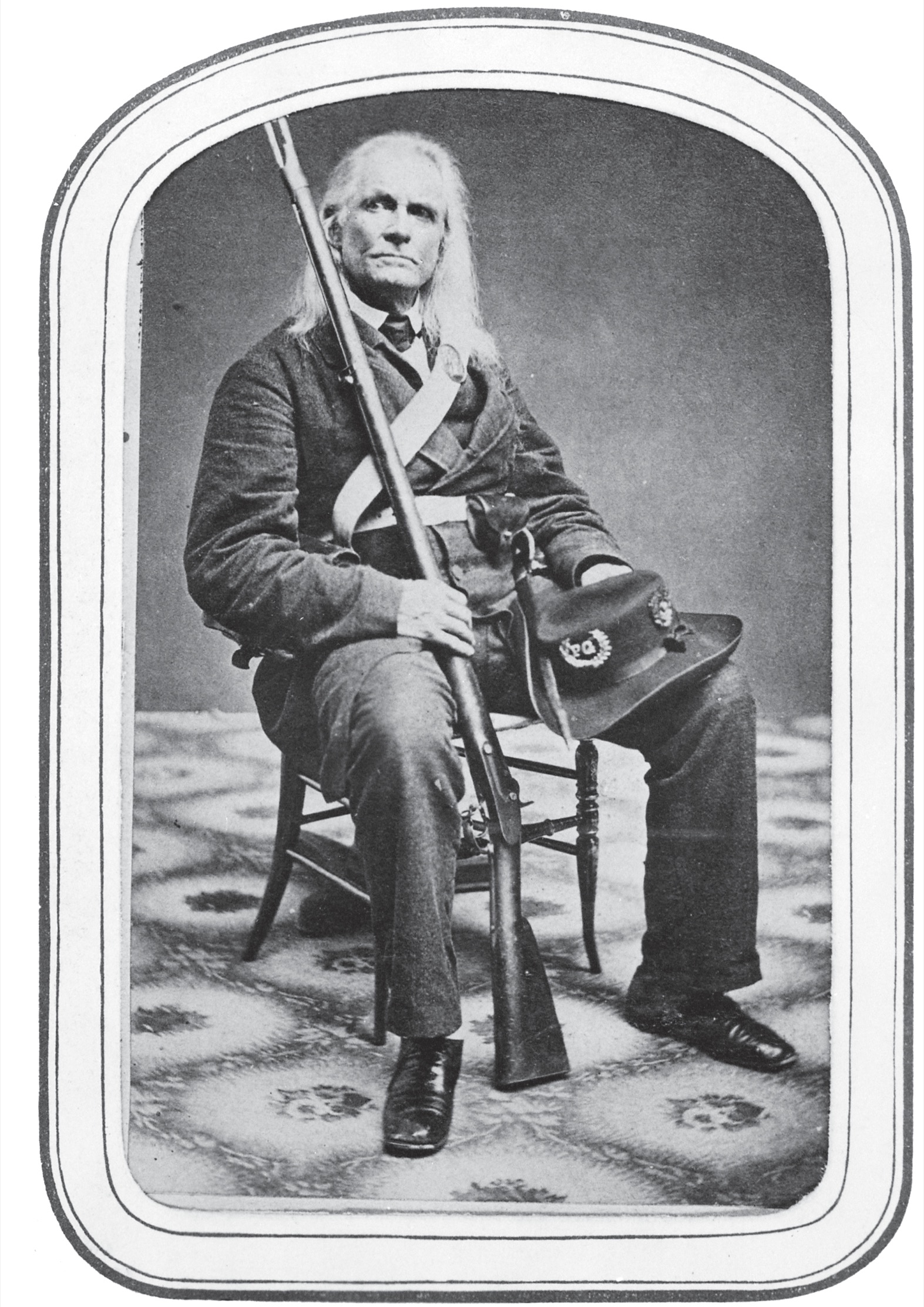

Edmund Ruffin considered himself the chronicler of the Civil War. He wrote down every detail he could, carrying on with ink he made himself once the Confederacy’s supplies began to run low. His profound emotional investment in the increasingly futile war did make some sense. After all, he had helped start it.

Long before the 1860 presidential election, the Virginian plantation owner and noted agricultural pioneer spent years writing passionately about the South’s need to preserve slavery in order to keep the plantations running. So, when abolitionist Abraham Lincoln was elected, Ruffin began to argue even more fervently that secession was the only possible path forward.

The purported drawing of the Hunley’s torpedo (left) and a drawing of Singer’s torpedo (right).

Ruffin decided to travel to wherever the action was, so that he could observe and record. At sixty-seven he was considered beyond the ideal combat age, but he insisted on joining the burgeoning Confederate military nonetheless. He had himself photographed proudly in his gray uniform, seated with his long rifle propped between his legs, shoulder-length silver hair swept back to reveal a stern, resolute, increasingly toothless face.

As a sign of gratitude for his influence pushing toward the decision to secede, Ruffin was given an honor he described as a “highly appreciated compliment.” He was asked to fire one of the first artillery shots to spark the entire war, at the start of the assault on then Union-occupied Fort Sumter. This privilege permanently secured him as a Confederate hero.

His status as a sort of founding father granted him an all-access pass to the inner machinations of the Confederate military, and he used this proverbial pass to witness and document as much as he could in tight, tiny handwriting, in the form of a diary that would eventually consume thousands of pages.* Despite his obvious political extremism, historians now consider Edmund Ruffin’s diary to be one of the most important firsthand accounts of the events of the war. More valuably, while he did sometimes record inaccurate information that he had received secondhand from newspaper articles, his actual observations have proven to be largely correct.

Diarist Edmund Ruffin.

In the fall of 1863, when he heard that the city of Charleston was under siege, he journeyed back down to watch and document the fighting. He was treated, as usual, as a VIP. General Beauregard himself heard of Ruffin’s arrival and provided him with a personal letter that let him go wherever he wanted to go, and see whatever he wanted to see, always with a hero’s accommodation and often with the use of Confederate vessels and troops as personal transport. Luckily for history, among the things he chose to observe and document were the submarine HL Hunley, the Confederacy’s other fish boats, and perhaps most important, their torpedoes.

Nestled in alongside his profoundly racist rants about the importance of slavery, Ruffin’s diary entries about the Hunley provide some of the only accurate contemporary descriptions of the boat. He carefully observed her length shortly after her arrival in Charleston, correctly declaring it to be “from 36 to 40 feet.” He went on to describe her shape, her dimensions, her bow and stern, her conning towers. Everything he said about the vessel has since been proven correct. He knew her strategic plan, and he knew that the original desired target for all the fish-boat privateers was the highly valued USS Ironsides. He wrote what is perhaps the only record that correctly recounted that there were eight men to her crew—most records, even historical ones, incorrectly claim there were nine—and he also saw her torpedo.

“The torpedo, in a copper case, cylindrical, with conical ends . . . It is more than double the size of the torpedo carried by the ‘David,’ which contained 75 lbs. of powder.” The conical ends precisely match the drawings and descriptions of Gabriel Rains about the pointy-ended torpedoes being built for the fish boats, but they stand in contrast to the rounded caps on the drawing from Gillmore’s files.

Ruffin later directly interviewed the men working on the torpedo boats, and asked them about the weapons they planned to use. This too he recorded diligently: “The torpedoes will also strike lower [in the water], & the charges of powder will be increased from 75 lbs to 200.”

Using basic scaling laws for explosions, increasing the charge weight from 135 to 200 pounds of powder should result in peak pressures in the water that are about 16 percent higher. Applying that increase to the full-sized 135-pound data point would yield 8,816 kilopascals in the water around the keel of the Hunley, and 143 inside hitting the crew. Those pressures would give each man a 98 percent chance of serious trauma, and a 42 percent chance of immediate death.

At the end of the war, depressed, lonely, and fraught with physical illness, Edmund Ruffin could not stand the thought of a Union victory and the inevitable end of slavery. He made one last diary entry vehemently declaring his inability to tolerate oppressive “Yankee rule.” Then he went upstairs, inserted the end of his long firearm into his mouth, propped the butt of the weapon on the ground, and used a forked stick to press the trigger.

Even though they are severe, the pressures I’ve calculated may still potentially be lower than what really happened. Blast scientists often use a concept called TNT equivalency, sometimes known as “relative effectiveness,” which gets abbreviated as “RE.” Through RE, all explosive types can be roughly compared to the common yardstick of TNT. For example, if a nuclear bomb has an RE of 4,500, that means that you would need 4,500 kilos of TNT to create the same amount of “boom” as one kilo of the nuclear-bomb material.

Higher numbers mean a stronger explosive material, and values below 1.0 mean that the explosive is weaker than TNT. It’s an unrefined and imperfect yardstick for many reasons—it does not inherently account for the slow rise times of black powder, or the long, drawn-out pressure waves of nuclear weaponry—but it still enables a rough kind of comparison.

RE values for black powder vary even more than for other explosives because of its highly fickle nature. The values can change because of the exact powder composition and method of manufacture, and they definitely change with varying levels of charge confinement. Underconfined charges will, unsurprisingly, underperform. For charges in air with a moderate level of confinement, such as a thick copper casing, the majority of the reported RE values in the scientific literature cluster just above 0.40. It is not perfect to apply these values to in-water tests, but they can still be used to calculate a rough theoretical estimate for the purpose of curiosity. Using an RE value of 0.40, the 200-pound charge would, in theory, have output the same maximum pressure levels as 80 pounds of TNT.

The peak pressures put out by an 80-pound charge would result in a 99.9 percent chance of serious injury, and a 92 percent chance of immediate death for each man inside the submarine. The crew would have also experienced at least a 46 percent chance of death from blast-induced traumatic brain injury, even if their lungs somehow escaped damage. As discussed earlier, blast-induced traumatic brain injury is subtle in its presentation, and it leaves the skull and the structure of the brain intact. Even in fatal cases, the only trace is a diffuse patch of blood that may or may not spread across the outer surface of the brain.

Several of the skulls of the recovered Hunley crewmen still, miraculously, held their intact brains. The soft tissues were severely damaged and shrunk by long-term exposure to salt water, but they were nonetheless carefully examined by medical personnel. Some of the brains had patterns of diffuse staining on their surfaces, and those stains appeared to be consistent with blood.

I had one measly hour in which I had to explain the last several years of my labor. A panel of five academic experts, including my adviser, each wielding a PhD and decades of experience in related fields, would sit in an auditorium and listen to me speak—and then judge whether I would receive a doctorate of my own. Pass or fail. Worthy or not worthy.

I did not need to convince them that the crew died from blast trauma in order to graduate. I just needed to convince them that my methods and analysis had been sufficiently thorough.

I coped with the stress-induced insomnia by baking thematically. I set up a table on one side of the room with a lemon cake from a recipe originating with Robert E. Lee’s wife, and an almond cake made famous by Mary Todd Lincoln. I also provided a large bowl of peanuts, a favored snack for both sides in the war during the lean times on the march.

My parents drove down from Michigan to sit near the front, in lecture-hall swivel chairs next to Nick. Friends from the hyperbaric chamber made the walk over from the hospital, giving me a wave and a smile as they climbed the stairs of the lecture hall to find seats of their own. My lab mates took the right-hand side of the room, there for support as always. Two of my coworkers on the naval base in Florida were streaming the defense live via webcam.

“If you pass, touch your shoulder,” one had emailed me beforehand. “I’ll be watching.” Before I began, I looked around at the friendly, familiar faces and had a moment of mental clarity. This room was filled with the people who had carried me through the project, supported me, helped me find the right resources, made sure I had food and clean clothes. They were here to see the results of their hard work too.

After the presentation is over, the committee takes a private moment to themselves to discuss their thoughts. As is normal, I was asked to wait outside, closing the heavy wooden double doors behind me to secure them alone in the lecture hall. My lab mates joined me, and we sat together in awkward, silent suspense. When the doors reopened, I was invited back in, and one of my committee members stuck out his right hand.

“Dr. Lance,” he said, “good work.” After the firm shake, I brought my hand up to my shoulder for my friend on the webcam.

Standing on the wrong side of the footbridge’s handrail, balanced on a crossbeam, I waved awkwardly at some Duke campus pedestrians who were too polite to ask questions. I wrapped a worn yellow ratchet strap around a solid metal part of the structure, and used every ounce of force I could muster to extricate the long wooden rails from the muck. After struggling to maneuver them over the handrails of the footbridge without falling in, I thought I was finally done with the project. But then a gust of wind blew my sun hat off my head and, before I could drop the rails to grab it, it flew away to land softly on the brown, still surface of the pond. Setting down the wooden planks, I kicked off my sneakers, swung my leg back over the handrail, and plunged feetfirst into the water one final time.