FIGURE 4.1

Sticky R&D Investment at the Industry Norm

Oligopolistic Rivalry and Routine Innovation Spending: Theory of the Engine of Unprecedented Capitalist Growth

competition of the kind we now have in mind acts not only when in being but also when it is merely an ever-present threat. It disciplines before it attacks.

—Schumpeter, 1947, p. 85

In this chapter we come to what, in my view, is the main influence explaining why the growth performance of the capitalist economy continues to be so different from that of all other economic forms. Using tools not much beyond the elementary textbook level, I will focus on a feature of free competitive markets to which I ascribe much of the extraordinary growth of the market economies. That feature is the process by which oligopolistic competition determines the level of innovation expenditure and its trajectory over time. That is, we turn now to the free-market economy’s production of innovation. I argue that this process is basically analogous to an arms race among mutually suspicious nations, in which each feels it necessary to be second to none in the weapons it has at its disposal. In more traditional terms, the appropriate model involves a kinked profit curve in profit–R&D spending space that keeps the individual firm’s R&D spending up to industry norms. The kink point here is constrained by the equivalent of a ratchet mechanism, which permits the spending norm to increase occasionally, but makes it difficult for firms to cut back their R&D outlays. This competitive arms race in innovation spending can also be described by what has been called (after Lewis Carroll) a “Red Queen game” (see Khalil, 1997), in which it is necessary to run as rapidly as possible in order just to stand still.

A second purpose of this chapter is to begin to show how easily routine production of innovation can be incorporated into the basic theory of microeconomics, even at the elementary-textbook level, which is the subject of part II of this book. We will see that elementary and standard treatment using only partial equilibrium methods yields substantive conclusions about the determination of the amount that a firm will invest in the innovation process.

The discussion uses a model of an oligopolistic industry, in which, as already suggested, most routinized innovation takes place. The model here takes no account of risk and uncertainty. Of course, the R&D devoted to any particular project—to the creation of any special new product or process—involves great uncertainties about cost, the time that will be required, or even whether anything useful at all will emerge. But here I will assume that the R&D activity of any firm with which we are concerned is on a scale sufficiently large to include a considerable number of such projects. Then, to simplify the discussion, one can assume that something like a law of large numbers applies, and that the overall value of the innovations that will emerge from the firm’s R&D is moderately predictable, even if that of any individual R&D undertaking is not.1

The heart of the story is the key role of oligopolistic competition in the process of free-market growth. Thus, it is my contention that one of the primary reasons for the failure of any other economic arrangement even to approximate the capitalist growth record for any considerable period is the absence of oligopolistic rivalry in those other economies. I need only add a word of explanation for the emphasis on oligopoly, with its small number of large competing firms, rather than any other market form. The answer, whether or not it is fully convincing, is straightforward. Monopoly will not do because, by definition, it is immune, or largely immune, from competition, and that can materially weaken its incentive to invest in innovation.2 At the other extreme, the small firms that inhabit a world of near-perfect competition or even monopolistic competition tend to lack the resources, they do not have the stimulation of observed interdependence with their rivals (there is no observable “race” among them), and the spillover problem may well prove particularly severe in such an environment. Almost by definition, it is only in oligopoly, where a few large (often giant) firms dominate a particular market, that competitive races among established firms can occur, and only in oligopoly that rivals observe and keep track of one another’s behavior.3 Those are the reasons, supported by extensive consulting experience with such firms, for my focus on this particular market form. Thus, almost all of the innovative rivalry we will be discussing occurs in the economy’s oligopoly industries. So, paradoxically, it is an economy’s oligopolies, which are often particularly suspect as a threat to the public interest, that may well prove to be the main industrial contributors to growth and standards of living.

TEMPORARY EQUILIBRIUM IN AN (INNOVATION) ARMS RACE

If it is true that in a number of high-tech industries innovation is the prime weapon of competition, a simple story emerges. The profit-maximizing firm will adopt the quantity of R&D expenditure at which expected marginal profit yield is zero. But this magnitude will depend on the behavior of the other firms in the industry. A firm that falls behind in its innovations for a substantial period of time can expect considerable erosion of its market either because its product is considered inferior by customers or because its costs, and therefore its prices, are higher than those offered by rivals for products of comparable quality. Consequently, no firm will in the long run dare to underspend its competitors systematically.4 Thus, one can expect an industry norm to emerge, with firms that engage in substantial R&D outlays generally making sure that their R&D expenditures are up to that norm.5 That norm will constitute an equilibrium in the arms race, but one that is only temporary—a truce, not a full end to hostilities.6

Still, firms will be tempted to exceed the equilibrium norm, and such enhanced spending would very likely be profitable if rivals could be counted upon to ignore the challenge and keep to their previous levels of expenditure. For that would enable our spoiler firm—the firm that upsets the tacit arrangement under which no player previously violated the industry spending norm—to outperform its rivals in terms of price and/or product quality and take customers away from them. However, each firm is aware that such passive reaction cannot be expected from competitors. Rather, the rivals are likely to respond by matching any spoiler’s increased rate of investment. The likely consequence of the spoiler’s initiative, then, is that the industry will end up with a new and higher R&D investment norm, but with none of the firms having gained any (relative) advantage over its competitors.

Total profits cannot be expected to be the same as they were before, once the spoiler firm has caused a general increase in R&D investment in the industry. Very plausibly, as in the case of rivalrous inflation of an industry’s advertising, the industry’s firms, including the spoiler, may well end up with less profit than before. This does not mean that increases in R&D expenditure will never occur. Rather, it implies that they will take place when the R&D effort of some firm has provided a highly promising breakthrough, calling for an increase in investment outlay whose profit prospects are unusually bright.

The net result of this scenario is a time trajectory characterized by long periods of fairly steady R&D spending, with each firm in temporary equilibrium, keeping up with the industry norm. Then, when breakthroughs occur, the norm will shift to the right and industry expenditure will remain at this higher level until the next stochastic shock stimulates further movement. So the arms-race model of R&D spending leads to a kink—a sharp change in pattern—in its profit relationship and a ratchet in its innovation spending levels. This may well be a key feature of the free-market economy that helps substantially to account for its growth record.

GRAPHICS OF THE ARMS-RACE MODEL OF INNOVATION PRODUCTION

We can make the technological scenario more explicit with the help of a microeconomic model explicitly based on Paul Sweezy’s kinked demand curve. That model is used to explain why prices apparently tend to “stick” in oligopoly markets. The underlying mechanism is an asymmetry in the firm’s expectations about its competitors. The firm hesitates to lower its price for fear that its rivals will match the price cut, so that the firm will end up with a few new customers but dramatically reduced revenues. On the other hand, it fears that, if it increases its price, its rivals will not follow suit, so that it will be left all by itself with an overpriced product. Thus, such a firm normally will set its price at the industry level, no more and no less, and leave it there unless the competitive situation changes drastically.

The innovation story is similar. Consider an industry with, say, five firms of roughly equal size. Company X sees that each of the other firms spends about $20 million a year on R&D. Company X will not dare to spend much less than $20 million on its own R&D for fear of falling behind in salability of its product. On the other hand, Company X sees little point in raising the ante to, say, $30 million because it knows that if it does so the others can be expected to follow suit.

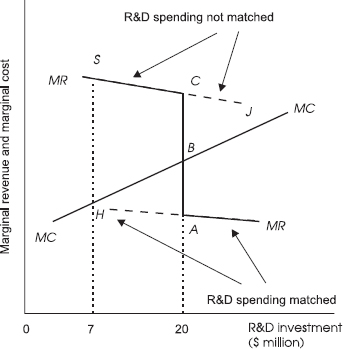

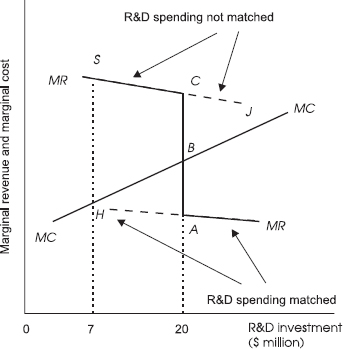

The story is described graphically in figure 4.1, which shows a marginal cost (MC) curve and two marginal revenue (MR) curves, MRJ and HMR, all as functions of the amount of R&D spending by Company X. For simplicity, the curves are drawn as straight lines. The MR curves reflect the two possible competitor responses. If each time Company X expands its spending its rivals do the same, the MR resulting from X’s enhanced R&D will be quite low (line HMR), because Company X will fail to pull ahead of its rivals. On the other hand, if competitors let X increase its R&D spending without increasing their own, then X can expect its increased product quality to put it well ahead of the others, and so its MR from R&D spending will be relatively high (line MRJ).

In figure 4.1, Company X expects mixed reactions from its competitors. They will follow its lead when it increases its R&D, but they will not follow any decreases. The result will be the Z-shaped piecewise-linear locus, SCAMR, with a vertical break between points A and C at the current level of R&D investment ($20 million in the example). The explanation is straightforward. If each firm in the industry spends $20 million a year and Company X were suddenly to decrease R&D spending—say, to $7 million per year—it has good reason to fear that competitors would not match that cut. With competitors still spending $20 million, Company X can expect to lose a good deal of revenue, and find itself moving backward along the “not matched” MR curve MRJ to point S. However, if Company X decides to increase its R&D spending above $20 million, it will move along the low “matched” MR curve (HMR). For its rivals will feel threatened and will match the increase.

FIGURE 4.1

Sticky R&D Investment at the Industry Norm

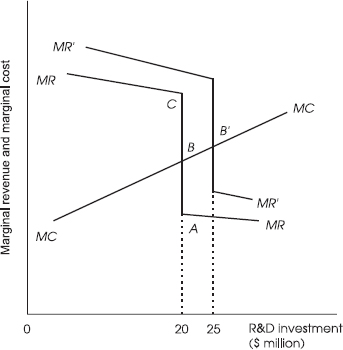

But that is not the end of the story. All five firms in the industry will continue to invest the same amount until one of them enjoys a research breakthrough leading to a very promising new product (as happens from time to time, particularly in high-tech industries). That fortunate firm will then expand its investment in the breakthrough product, because doing so will pay off even if the other firms in the industry match the increase. The piecewise-linear MR curve for the breakthrough firm will shift upward and rightward (figure 4.2) from MRBMR to MR´B´MR´, and its MC = MR point, B´, will move to the right, to an amount larger than $20 million ($25 million in the graph). Other companies in the industry will feel forced to follow. So now the industry norm will no longer be a $20 million investment per year, but will instead be $25 million per firm. No firm will dare to drop back to the old level, fearing that no other company will follow such a retrenchment move. Again, the common story of armaments races among countries parallels the story of innovation battles among firms.

FIGURE 4.2

Shift in the Industry’s R&D Investment Norm

In game-theoretic terms, the arms race that has just been described can be interpreted either as a prisoners’ dilemma game, or as a Red Queen paradox. The payoff matrix is obvious. It entails the highest payoff to both (all) parties if they can conclude an effective disarmament treaty, a collusive arrangement in which both agree to keep expenditure on R&D to a minimum. However, as in the story of so many cartels, we can expect little trust among the parties because each knows that if one of them can successfully conceal a massive investment in R&D it will perhaps steal a march at their expense, earning huge profits while the others’ returns are low or even negative. Moreover, the antitrust institutions make direct communication difficult. Consequently, the firms all end up spending heavily on the innovation process, with a moderate profit—perhaps close to zero economic profit—to all. The payoff matrix is, of course, thoroughly familiar.

The process just described is, in effect, equipped with a ratchet. It is an arrangement that holds R&D spending steady, permits it in certain circumstances to move forward, but generally does not allow it to retreat.7 R&D spending can then be expected to expand from time to time, but once the new level is reached, the ratchet—enforced by the competitive market—prevents a retreat to the previous lower level.8 It is at least highly plausible that this is a critical part of the mechanism that accounts for the extraordinary growth record of free-enterprise economies and differentiates them from all other known economic forms, with ever-growing R&D expenditure norms leading to ever more rapid growth.9 It is competitive pressures that force firms to run as fast as they can in the innovation race just to keep up with the others.

The main shortcoming of this analysis, aside from its omission of both strategic issues and general equilibrium considerations, is that it does not explain how the initial industry norm of R&D spending is selected. It merely tells us that, once selected, it will tend to persist, and that, when things change, the moves will generally be toward the right of the previous norm. But this indeterminacy may be a feature of reality rather than a deficiency of the model. It is a consequence of the nature of the issue we are studying, in which there exists a continuum of potential equilibrium levels of expenditure. Any R&D expenditure norm for an industry can become an equilibrium if history and its fortuitous circumstances make it so. Oligopoly equilibria and the character of breakthrough innovations that influence their intertemporal trajectory are inherently unpredictable. One cannot expect a theoretical model to be able to determine what in reality is inherently indeterminable.

THREE GROWTH-CREATING PROPERTIES OF INNOVATION

We have just discussed reasons to expect that the market mechanism will force firms to devote at least a steady stream of expenditure to innovative activities. With luck, the resulting R&D effort will be level and will yield a fairly steady flow of innovations. But a steady flow of innovation does not mean that GDP remains constant. Rather, a level flow of innovation can result in steady growth of the economy’s output.10 Here we must take note of three critical features of innovation that can, so to speak, magnify the contribution of technical change to the economy’s GDP:

1. The cumulative character of many innovations. Many innovations do not merely replace older technology and make that technology obsolete; rather, they add to what was previously available, thus constituting a net increase in the economy’s store of technical knowledge. Such innovations can be said to entail creative knowledge accumulation rather than creative destruction.

2. The well-known public-good property of information in general, and of innovation in particular. Improved technology, once created, need not contribute to the output only of the firm that made the breakthrough. At relatively little additional cost, it can also add to the outputs of other enterprises. Thus, although this public-good property can impede attainment of the optimal amount of innovation expenditure, it also has a beneficial side, constituting an economy of scope in the generation of technological improvements for a multiplicity of firms.

3. An” accelerator” feature of innovation. A level stream of innovation usually means that output will be not level but growing. An economy whose R&D produces a level output of one innovation per month, with a given productivity contribution, will obtain a GDP that is higher each month than it was in the previous month. The economy’s ability to produce output will grow constantly even though the flow of innovations that fuels that output growth remains level at one invention per month.11 This acceleration relationship applies to innovation generally, so that, if the competitive market mechanism described in the previous graphs leads firms to devote a constant level of resources to R&D, we would expect continued growth of GDP to result.

Of course, as noted, the ratchet principle tends to increase the expenditure of resources on innovation, not just to leave them level. Our acceleration principle tells us about the effects of this, too, if there are no diminishing returns to R&D innovation productivity (but note the Jones argument described in footnote 9 above). The acceleration relationship indicates that, if the level of R&D spending were to increase just once, for example, and then stay at that new higher level forever, the growth rate of GDP would also move upward. GDP would then grow at a faster rate forever.

All of this reinforces the role of the competitive market mechanism and its stimulation of innovation as a contributor to the extraordinary growth that characterizes the world’s free-enterprise economies. But at this point one may well pause to ask whether the analysis does not exaggerate the facts. It tells us that R&D investment norms can be expected to increase from time to time, and that the ratchet serves to resist retreat to the previous lower investment levels. This then implies that the GDP growth rate can be expected to keep rising, and the natural question is whether history is consistent with such a picture. The answer is, in fact, yes, but before we show this, let us be clear that the analysis never asserts that this must continue forever. For example, R&D personnel may find it increasingly difficult to come up with good new ideas, so that, even if more and more is spent on R&D, it is conceivable that, some day, its results will be worth less and less.

But what about the facts? Of course there have been decades during which catastrophes such as wars and depressions have kept GDP from rising or have even reduced it. But ten-year periods are too short for the evaluation of the long-run performance of market economies. We can say that there have now been about six half-centuries since the modern free-market economy made its debut. The first half of the eighteenth century is generally taken to have preceded the birth of the British Industrial Revolution, with GDP per capita consequently rising more slowly than in the second half. And, during the century as a whole, GDP per capita in Western Europe surely rose a substantial amount, but one that was less than 50 percent.12 In the nineteenth century we observe a similar pattern, with relatively modest growth even in England until after 1830, and in France, Germany, and the United States until well after that. Thus, growth in the second half of the century was presumably higher than in the first, and in the century as a whole per capita GDP in Western Europe did something between doubling and trebling—far better than the previous century. The twentieth century’s growth, too, sped up during its second half and, remarkably, per capita GDP ended up seven or eight times as large as it began.13

CONCLUDING COMMENT

This chapter has provided a concrete model that can help us to understand the role of competition among high-tech oligopoly firms in the remarkable growth record of the free-enterprise economies. It is an arms-race model with the addition of the ratchet attribute of innovation investment. The first of these features—the arms-race analogue—can explain the presence of powerful norms for R&D investment in leading oligopoly industries. The ratchet, in turn, implies a propensity of such an industry not to retreat from the current standard for R&D spending, and occasionally to move to a new and higher standard that all major firms in the industry are apt to feel they must match.

Let me emphasize here that the scenario described in this chapter does not stop at the invention portion of the story. The competing oligopolies are obviously not usually content to let promising inventions languish in the companies’ research facilities. Indeed, the firms normally have built into their structure the organization and the personnel whose task it is to prepare process inventions for adoption into the company’s production processes, to prepare new products for market, and to carry out their introduction. In short, the oligopoly firms routinize not only inventive activity but the entire innovation process, thereby ensuring its long-run continuation. As this book maintains, it is the presence of the full innovation process, and not just its invention component, that most directly differentiates the capitalist growth mechanism from that of all other economic arrangements. All this, then, is at least a worthy candidate for the role of the Prince of Denmark in our performance of Hamlet.

___________

1. The applicability of the law of large numbers here must not be exaggerated. The law would apply fully only if the chance of success of one R&D project does not depend on the success of others. Where they are interdependent, failure in one may sink many others, making innovations something nearer to a “house of cards” activity.

2. However, one should note that only monopolies, notably the old AT&T with its Bell Laboratories, seem to be in a position to carry out substantial basic research, particularly if they are regulated and regulation permits them to recoup their research outlays. Another part of the explanation lies in the heavier spillovers that basic research generates, discouraging such activity by competitive firms, which fear that too much of the benefit will go to competitors. I also recognize that innovations are often contributed by small firms (see the next chapter) but, except when it is carried out by trade associations, it is rarely routinized. Here, Schumpeter’s views on the role of large firms in innovation should also be recognized.

3. And oligopolistic industries are important for the economy not only because of their role in innovation. In addition, they probably constitute the largest share of U.S. output, and the revenues of the largest oligopoly firms outstrip the gross domestic products of entire economies such as Denmark and Norway.

4. Witnesses in patent litigation lawsuits or antitrust cases involving competing technology repeatedly testify (and internal firm documents confirm) that the firms try avidly to keep track of the innovative activities of their rivals in making their own plans. The market-leader firm’s management is often concerned about the catch-up plans of its nearest rival, and that rival measures its performance and its reputation in terms of quality of technology against that of the market leader. I offer no specific citations because of court-imposed confidentiality rules.

5. Recall Schumpeter’s characterization of the role of competition: “in capitalist reality as distinguished from its textbook picture … [the] kind of competition which counts [is] the competition from the new commodity, the new technology … competition which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives” (1947, p. 84). Or, as Nelson puts it, “given that its rivals are induced … to invest in R&D a firm may have no choice but to do likewise” (1996, p. 52).

6. The nature of this “norm” is deliberately kept vague here, because in practice firms follow one another’s spending practices only roughly and approximately. This is partly because no two firms are perfectly alike, nor are the attitudes of their managements. Partly it is so because firms may be imperfectly informed about the R&D spending of their rivals. The norms may be vaguely based on sales, assets, market shares, or other criteria, or on a combination of these.

7. In chapter 14, it will be assumed that these outlays are fixed in nominal terms. This does not affect the argument here, but it does play an important role in the macro growth model in which the cost of R&D can change cyclically.

8. This statement somewhat exaggerates the effectiveness of the ratchets in preventing the economy from ever sliding backward in its expenditure on R&D. After all, even in machinery, ratchets sometimes slip. In R&D investment, firms may, for example, be forced to cut back their R&D expenditure if business is extremely bad; or they can simply make mistakes in planning how much to spend on investment; or they may be discouraged by repeated failures of their research division to come up with salable products. The economy’s ratchets are indeed imperfect, but they are there. They cannot completely prevent backsliding in R&D expenditure, but they can be a powerful influence that is effective in resisting such retreats.

9. Jones (1995) has argued that there are sharply diminishing returns to R&D effort, on the basis of data for research employment in the period 1950 to 1988. These apparently expanded more than fivefold while total factor productivity growth was “relatively constant or even declining.” However, McGrattan (1998) has disputed this conclusion. She provides longer-term data suggesting that returns to R&D effort do not decline nearly as sharply as Jones implies, if they decline at all. In any event, the argument on R&D spending here does not depend on the outcome of that discussion, but does assume that the marginal return to R&D activity is positive. For studies showing this, see Griliches (1992, p. 45) and Nadiri (1993, p. 11).

10. Here the word “steady” means “continuing” and is not meant to deny the possibility of diminishing returns.

11. This does not, of course, mean that there is a fixed relationship between R&D spending and rate of growth of the economy’s output. All that is assumed here is that a rise in R&D will generally increase growth to some degree relative to what it would have been otherwise, other things being equal.

12. Indeed, according to Maddison’s calculations (2001), this is all per capita GDP rose between 1500 and 1820.

13. There are noted analysts who argue that the true figure was far greater than this. See, for example, the work of William Nordhaus (1997). DeLong (2001) adds: “William Nordhaus brackets the growth of real wages over the past century as somewhere between a 20-fold and a 100-fold increase. Alan Greenspan—Chairman of the Federal Reserve—has [suggested adjustments of the statistics that lead] to an estimate of a thirty-fold increase in material wealth over the past century.”