Recouping Innovation Outlays and Pricing Its Products: Continued

technological knowledge is itself a kind of capital good. It can be used in combination with other factors of production to produce final output, it can be stored over time because it does not get completely used up whenever it is put into a production process, and it can be accumulated through R&D and other knowledge-creation activities, a process that involves the sacrifice of current resources in exchange for future benefits. In all these respects knowledge is just a kind of disembodied capital good.

—Aghion and Howitt, 1998, pp. 25–26,

summarizing Frankel’s analysis

This chapter continues with analysis of the financing of innovation, treating expenditure for this purpose as just another of the firm’s portfolio of investments. It focuses on the intertemporal pattern of final-product prices that returns the investment in a manner compatible with economic efficiency. The analysis will illustrate once again the ways in which our theoretical work becomes easier when we recognize that decisions on routine investment in innovation are very similar to those on other types of business investment; indeed, many parts of those decisions are formally identical. In particular, this is because the grand budgeting decisions of the firm weigh the alternative investment options using similar and obvious criteria for them all: costs, probable returns, risks, and length of time before the returns can be expected. Investment in plant and equipment and investment in research facilities and activities clearly are among these competing demands for the resources of the firm. Both types of investment inherently entail “waiting,” that is, the passage of time before the funds tied up begin to generate revenues. In addition, if management foresees the need to increase output in the future, it can plan to do so either by acquiring new plant and equipment or by adopting innovations that increase productivity. Consequently, at least to a degree, the two types of investment are substitute inputs for the production process.

This chapter focuses on such productivity-enhancing process innovations. It is convenient to think of an innovation of this sort as a modification of equipment design or production procedures that increases the productive capacity of a given plant and set of equipment. There are many real examples. Some of these innovations have enhanced capacity directly, for example the technical advances that have increased the amount of petroleum that can be extracted from an oil well, or those that permit the spectrum used in telecommunications to carry data as well as voice, without any crowding of the latter. However, any innovation that increases the productivity of capital can clearly be interpreted as I do here.

These observations suggest that one can turn to a standard model of capacity-increasing investment to analyze a number of the basic decisions of the firm on its research and development (R&D) activities. This chapter describes one such model and shows how the model can be used to calculate the optimal intertemporal trajectory of R&D investment outlays, how those outlays affect the pricing of the firm’s final products, and how the investments are, optimally, amortized and depreciated. Thus, the chapter will study the fundamental financial decisions involved in that investment process. Using examples somewhat more sophisticated than that of the previous two chapters, the discussion will also show how standard analysis lends itself directly to study of the economics of routine innovation.

PRELIMINARY: PRICES, INNOVATION, AND THE INFORMATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE MARKET MECHANISM

Before turning to the central material of this chapter it is well to deal briefly with a more general issue. Earlier, I made two assertions that require some assessment, and whose role is suggested by the analysis that follows here. The first, following Schumpeter, is that, in many firms, innovation has replaced price as the primary instrument of competition. The second assertion is the claim that innovation belongs at the core of microeconomic analysis, rather than on its periphery.

But here we must face up to the critical role that price plays in standard microeconomics and general equilibrium theory. The price mechanism is surely the bloodstream that keeps the economic body in operation and guides its workings. In particular, theorists have repeatedly pointed out the extraordinary efficiency and effectiveness of price as a conveyor of the information that decision makers need in order to make rational choices. We all know the story: at its most elementary level, if, say, production of good X exceeds the amount that is demanded on the market, its price will automatically fall, demand will be stimulated, and the incentive for production will decline, moving both quantity demanded and quantity supplied toward equilibration.

Nothing to be said here is intended to replace that story, but only to supplement it. The point is that, even at this elementary level, the mechanism is not moved by price alone. Instead, the scenario really deals with the interaction between price and resource allocation. In other words, there are two starring actors here, not just one. Indeed, as the story of the previous paragraph is recounted in elementary economics textbooks, this often comes out clearly. The initial fall in prices may bring the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded closer together. But, if the supply still exceeds demand, this forces prices to fall still further, and so on, in the familiar sequence of steps toward equilibrium. What is fundamental here is not the movement of price or that of quantity, by itself. It is their interaction that constitutes the mechanism.

In a dynamic setting, the same is true of the interplay of prices and innovation investment, among other variables. It is this interaction that determines the profitability of the allocation of resources to innovation and other growth-promoting activities. In any defensible microeconomic analysis of the growth process as a general equilibrium or a general disequilibrium construct, then, innovation, but not innovation alone, must be given an explicit and prominent role. Price is not to be excluded from the story. Rather, it is the interaction of price and investment in innovation that, I maintain, is fundamental. The analysis that occupies the remainder of this chapter is meant to provide a preliminary indication of a way in which such interactions can be approached.

ASSUMPTIONS OF THE MODEL

Because of the direct substitutability between investment in (certain types of) innovation and investment in the capacity of the firm’s plant and equipment, it is legitimate and convenient in the discussion of this chapter to think of R&D expenditure as just another means to increase the output capacity of the firm. Since the outcomes of even routine innovation outlays can be highly uncertain I will, without constantly noting that I am doing so, deal in expected values of the stochastic variables rather than with magnitudes known with certainty. In terms of risk and uncertainty, of course, the difference of innovation expenditure from other types of investment is a matter of degree, since the future returns to investment in plant and equipment are also far from riskless. There are, of course, well-known deficiencies in the use of expected values to deal with risk, which, it is sometimes suggested, amount to sweeping the complications of uncertainty under the rug. However, here it does not seem essential to face up to the problems explicitly.

More troublesome is the characterization of the innovation process as something that only adds to the firm’s output-producing capacity. Obviously, innovation often does much more than that, most notably providing new products or valuable modifications of existing products. However, if I treat the result as an expansion in the firm’s ability to produce revenues rather than as tangible physical outputs, it should be possible to apply the model to routine innovation more generally. That is, it can be applied to product innovations as well as to process innovations.

An important feature of an investment is its impermanence. It is generally durable, but it does not last forever. Plant eventually deteriorates, but so do inventions, by becoming obsolete. This erosion in the productive powers of an investment can follow many patterns. An extreme scenario is the one-horse–shay model, in which the productive power of the investment does not decline at all with the passage of time, until the date of its demise. At that point the investment suddenly becomes totally useless, in one moment being transformed from a perfectly operational item to a piece of junk. This scenario is easily dealt with in a model very similar to the one that follows.1 However, here the discussion will focus on a more gradual intertemporal trajectory of the decline in productive powers of an innovation investment. It will be assumed that the rate of decline is constant, so that the capacity contributed by an asset falls by a fixed percentage every period (call it “a year”) in the life of the asset. The parable underlying this illustrative choice of intertemporal trajectory is straightforward. We can think of an innovation that increases the productivity of capital as one that leads to modification of the design of new equipment produced at the time the innovation becomes available, and for a limited period after that. Further innovations of this sort continue to emerge from the R&D activities of private firms, and lead to gradual retirement of the equipment that used the earlier innovation. In that way the productivity contribution flow of each such innovation undergoes a gradual decline, approaching zero asymptotically.

The discussion will also be simplified by assuming that there are constant returns to scale in investment in R&D (though a remark will indicate how that premise can easily be eliminated). In that case the rules that the mathematics yield on the optimal timing of investment outlays, on optimal pricing, and hence on depreciation policy are easily described.

1. Investment in the innovation process should, of course, be carried to the point where the present value of its expected marginal revenue yield is equal to its marginal cost.

2. During any years in which the flow of innovation produces unused capacity, because either demand proves to be low or the capacity contributed by the R&D process is great,2 the optimal price of the firm’s final product should cover only operating costs (i.e., short-run costs). For, in such a period, long-run marginal cost is equal to short-run marginal cost. Therefore, that price includes zero contribution to depreciation and amortization.3

3. During the years when the asset is used to capacity, the depreciation charge should be determined by the demand function, and consumers should be charged the price that just induces them to purchase the asset’s capacity output. The difference between that price and marginal operating cost constitutes the depreciation payment for the period in question.

4. This peak-period price is apparently determined by demand relationships rather than by cost (since the price is the one that just reduces the quantity demanded to the capacity level). Nevertheless, over the lifetime of added capacity, the sum of its depreciation contributions will just add up to the marginal R&D cost of an increase in capacity. Where there are constant returns to scale, such pricing of the products of the innovation will bring in, over the asset’s lifetime, total revenues whose present value just suffices to cover the investment outlay.

The rationale for the second and third rules is straightforward. For this purpose it is useful to think of the depreciation problem as an intertemporal peak-load pricing problem. The years in which the capacity provided by investment in R&D is fully utilized are the peak periods. It follows that, during “off-peak” years, increased use of (the excess) capacity is always desirable so long as marginal operating costs are covered. That is precisely why no contribution to depreciation is included in price for such a period. However, once the quantity demanded exceeds capacity at a price that makes no contribution to recovery of investment outlays, price becomes the required rationing device. It equalizes the quantity demanded and the amount of output that the firm’s physical assets and the innovations contributing to their productivity are able to produce.

The irrationality of a depreciation policy that demands the same contribution toward the cost of an asset in periods of both heavy and light usage is now easy to see. It is not too dissimilar in character from the curious commuter discounts that, in effect, make it cheapest to travel through tunnels or over bridges precisely at the times of day when they are most crowded. Both simply compound congestion and offer no incentive for increased utilization when there is unused capacity.

I shall later discuss the intuitive explanation of the fourth rule: the paradox that a set of prices apparently determined exclusively from demand information turns out, ex post, always to cover exactly the cost incurred in creating the capacity-yielding innovation.

DERIVATION OF THE RULES FROM THE BASIC MODEL

This section derives the preceding rules. The model’s basic assumption is that the firm can add capacity during any period by increasing its investment in R&D. I use the following notation:

pt = |

the present value of the anticipated price of output during period t; |

xt = |

the quantity of output during t; |

yt = |

the output capacity created during t; |

it = |

the total remaining capacity in period t of all assets purchased before period 1; |

c(x1, …) = |

the present value of the stream of total operating costs; |

g(y1, …) = |

the present value of total R&D investment costs; |

u(x1, …) = |

an (unspecified) money measure of the total (social) utility of outputs. |

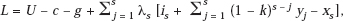

I take maximization of total net benefit (consumers’ utility minus the capital and operating costs of output) as the social welfare objective. To deal with the profit-maximizing firm we need merely reinterpret the utility function as a total revenue function. I will note later how this modifies the analysis. For now, the objective is to maximize

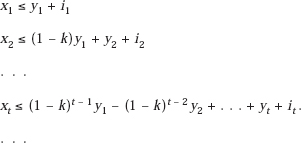

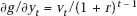

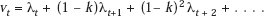

subject to the production capacity constraints that take into account the decrease in net productivity of past R&D investment with the passage of time as a result of obsolescence.4 I assume that, because of retirements of assets incorporating the innovation in question, the assets whose capacity was y1 in the initial period have only capacity y1(1 − k) in the next period and a capacity y2(1 − k)2 in the period after that, and so on. Then the constraints of our maximization problem become

Observe that the set of constraints is not finite in number since, under my assumptions, the productivity of an R&D investment never erodes completely, though a horizon date can be built into the model without great difficulty. After t periods of aging, an investment’s capacity contribution will be reduced from its initial value, y, to (1 − k)t y, which approaches zero only asymptotically. We then have as our Lagrangian for the Kuhn–Tucker calculations

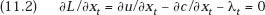

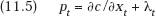

where s is a time period not necessarily the same as t. Assuming that some output is sold in each period (all xt > 0), this yields the following first-order conditions:

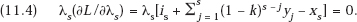

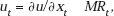

In addition, assume that some R&D investment occurs in period t, so that yt > 0. We then have

or

Last, we have the Kuhn–Tucker conditions

Let us now eliminate the undefined utility function from our analysis by noting that, for the usual reasons,5 ∂u/∂xt = pt [(relative) marginal utility equals (relative) price]. Substituting this into (11.2) we obtain

This states that optimal prices must include a nonnegative payment, λt, over and above the operating cost of the output in question. This payment will be interpreted as a depreciation charge—the contribution to recovery of investment outlays, including interest.

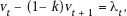

From (11.4) we see that in a year in which output is not up to capacity, that is, in which xt < it + Σs ≠ t (1 − k)sys, we must have λt = 0; in other words, in that year there will be a zero depreciation charge. This is the first of the depreciation rules of the preceding section.

Equation (11.3) now is readily interpreted as the fourth depreciation rule: the sum of the depreciation payments on the additional output made possible by a unit of investment in R&D is equal to the marginal R&D investment cost of that output. Consider an R&D investment that occurs in period t. The sum of the discounted depreciation payments on its outputs is λt + λt + 1(1 − k) + λt + 2(1 − k)2 + …. But since yt > 0, we know that (11.3) must be an equation, so that these depreciation payments will then equal ∂g/∂yt, the marginal cost of yt. This is the last part of the optimal depreciation rules of the preceding section.

All of these results are essentially affected in only one way if, instead of maximization of social welfare, we consider maximization of the profits of the firm. As already noted, in this case we need merely interpret u(x1, …, xn) to be total revenue. Then our maximand u(x1, …, xn) − c(x1, …, xn) − g(y1, …, yn) obviously represents the firm’s total profit. This leaves unchanged every one of the equations except (11.5), in which the product price, pt, appears. For, except where price is fixed and independent of the size of output, we now have, in general, instead of ut = pt,

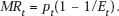

where MRt is the marginal revenue of output x in period t.

However, it is not implausible that, for a wide variety of products, elasticity of demand does not change very rapidly over time. In the possibly special case where the elasticity, Et, is (approximately) constant over time and cross-elasticities are relatively small, then, by the standard relationship,

So prices and marginal revenues will vary proportionately from period to period. In that case, (11.5) and all subsequent relationships that contain pt will be affected only by multiplication of pt by a constant. In terms of relative inter-period prices, absolutely nothing will have changed. The firm will then find it most profitable to set relative prices and depreciation rates exactly as is required for maximization of social welfare.

THE EFFECTS OF INFLATION, INTEREST RATE, AND TECHNICAL CHANGE WHERE INNOVATION OCCURS IN EACH PERIOD

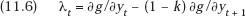

I will now derive some remarkably simple depreciation rules that apply in the special case where demand grows so rapidly that assets are used to capacity in the period in which they are installed, and new capacity will be needed in each succeeding period. In terms of the innovation model, this assumption means simply that R&D investment in process innovation is nonzero in every period, a premise usually satisfied in reality by high-tech firms. Since, by assumption, yt > 0 in every period, (11.3) is an equation rather than an inequality. Comparing this equation (11.3) for period t with the corresponding equation for period t + 1, we obtain at once as an expression for the present value of the depreciation payment

Equation (11.6) can be considered the fundamental relationship in the model in which the productivity contribution of an innovation declines with age at a constant rate. Its interpretation helps to explain the logic of the entire analysis. Suppose output increases by dx1 units above current capacity. This means that capacity in period 1 will have to be increased by dy1 = dx1 units at a cost (∂g/∂y1)dy1. In the following period, however, (1 − k)dy1 units of this new capacity will still be available. This will permit a corresponding reduction in next period’s R&D expenditure, yielding a saving in that period of (1 − k)dy1(∂g/∂y2).

Following Turvey (1969), in this case I define the long-run marginal investment cost of output as the R&D cost it incurs in this period minus the investment cost it is expected to save in the following period. For dx1 = dy1 = 1, this marginal cost is ∂g/∂y1 − (1 − k)∂g/∂y2, and, for any period t, this marginal innovation cost is given by the right-hand side of (11.6). Thus (11.6) tells us that in the model, assuming the R&D process increases capacity in every period, the optimal depreciation charge, λt, is equal to the present value of the expected marginal R&D investment cost of output in period t. Similarly, we may now interpret (11.5) to state that price should equal long-run marginal cost, which is equal to the sum of marginal operating cost, ∂c/∂xt, and marginal investment cost, λt.6

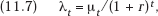

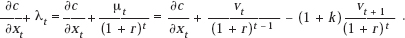

So far, the analysis has all been expressed in terms of discounted present value. Since, in practice, investments and prices are all expressed in current dollars, it will be useful to translate some of the relationships into current dollars to examine explicitly how they are influenced by the discount rate and other relevant parameters. For this purpose, let r be the discount rate and let vt be the value of ∂g/∂yt expressed in dollars of period t so that

and7

where μt is the number of dollars of depreciation accumulated in period t. By substitution of expressions (11.7) into the depreciation equation (11.6), we obtain

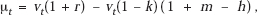

By the definition of ∂g/∂yt and (11.7), vt is the marginal dollar cost of capacity in period t. Suppose that because of technological progress in R&D activity the real marginal cost of a unit of capacity is expected to decrease at the annual rate h, but because of price inflation this is (at least) partly offset by a rise in money cost at rate m per year. We then have

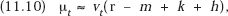

Substitution of (11.9) into (11.8) gives

so that multiplying through and dropping the terms mk and −kh, which are presumably small,

or, if we wish to put the matter in terms of the real rate of interest r* = r − m, we obtain

This rule, it must be emphasized once again, is valid only if growth is sufficiently rapid for capacity to be needed in each period so that R&D investment, yt > 0 for every t.

INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULT

Equations (11.9) and (11.10′) are the basic rules determining the optimal depreciation policy if innovation occurs in every period. It may be helpful to discuss them further in more intuitive terms. Equation (11.10′), which is a little easier to interpret than (11.10), gives μt, the depreciation component of the period t price of the final product produced with the aid of the innovations in question. It asserts that this should be proportional to vt, the dollar R&D cost per unit of added capacity in that period. Obviously, the ratio between the two is required by (11.10′) to vary directly with h, the annual rate of reduction in the expected R&D cost of additions to capacity, and with k, the rate of decrease in the net productivity contribution of R&D investment. It also varies directly with the real rate of interest, r*. Finally, it varies directly with m, the annual rate of increase in the price level, since vt is raised correspondingly above vt − 1.

Intuitively, the rationale of the relationships is easily described. Technological changes that reduce the costs of added capacity with the passage of time make it desirable that demands be postponed until less expensive capacity becomes available. Hence, the optimal current depreciation charge is increased by a rise in the value of h as a means to discourage current demand. Similarly, a high real discount rate, r*, calls for postponement of investment since it makes a future R&D investment less expensive relative to an earlier investment, and so, like a high value of h, a high r* increases optimal depreciation charges. Rapid deterioration in the productivity contribution of an innovation (a high value of k) and higher prices (higher m) simply mean that more money must be collected each year of its life to cover the cost of investment.

SOME REMARKABLE PROPERTIES OF THE SOLUTION

This solution of the depreciation problem seems reasonable enough in terms of economic principles. Perhaps the only surprising property to emerge so far is the conclusion that the depreciation payments called for by the calculation appear to add up, automatically, to the marginal cost of capacity. They do so even though that was not imposed in advance as a requirement for the solution, and even though the magnitudes of the depreciation contributions, in the peak periods in which they occur, are determined not by costs but by demands. Here, demands enter through the requirement that final-product prices be those that reduce the quantities demanded to available capacity. The reason the depreciation payments always add up to the cost of capacity is because the model is set up to determine, not only the optimal values of prices and depreciation payments, but also, for each period, the size of the optimal addition to capacity. That is, the act of magic consists of dealing not with some arbitrary level of investment, but with the amount of investment that satisfies the optimality conditions.

Here, it is helpful to think of the sum of the depreciation payments, Σ(1 − k)t λt, as the total rental values of the investments. Obviously, if the R&D investment program is optimal, its marginal cost, ∂g/∂yt, must be equal to its total lifetime rental revenue per unit; otherwise it would pay either to increase or to decrease the quantity of investment. So it is only because investment in innovation is carried to the optimal level that the demand-determined depreciation payments per unit of capacity must always add up to innovation costs per unit.

Under my assumption that the expected magnitude of added output capacity increases linearly with R&D investment, rental prices equal to marginal (= average) investment cost will yield total revenues just equal to the total R&D investment outlay. However, if there are increasing or diminishing capacity returns to investment in R&D, total revenues at rental prices equal to marginal costs will obviously not equal R&D investment. In that case, second-best optimal rental prices that do cover total investment cost will of course have to be Ramsey prices.

There are (at least) three other noteworthy properties of the solution, the first two perhaps of interest primarily for pure economics. The third, rather remarkable, characteristic, which Kenneth Arrow has called “the myopic property,” may also be important for application.

The first of these three properties is the conclusion that the λt, the depreciation payment in period t, is equal to the marginal net social yield of added capacity in period t. That is, the unit depreciation payment in any period is equal to the marginal productivity of added capital in that period. This is, of course, what neoclassical analysis should lead us to expect: optimally, an input will be paid its marginal yield, and that is how I conclude that the λ’s are the rental values of the capacity in question. The proof of the property follows at once when we recognize that the λt, the Lagrange multipliers of the Kuhn–Tucker maximand, are necessarily the structural variables of the dual program. Since, as is well known, the dual variables are the marginal yields corresponding to the limited inputs of the primal problem, we have the first of the three results.

The second of the solution properties is equally easy to derive. It states that two apparently independent definitions of the depreciation problem are both satisfied by the solution. The economic depreciation problem can, clearly, be defined as the answer to one or the other of the following questions. First, how much has the economic value of a given (earlier) addition to capacity (derived from an R&D investment) decreased in the period in question? Second, during the period, what is the (optimal) payment to be charged to consumers toward recovery of the cost of the R&D investment, over and above its marginal operating cost? So far, the discussion has addressed itself to the second of these questions, and the solution may at first glance appear to have no necessary relevance for the first. However, once having selected a set of consumer prices that satisfies the requirements implied by the second question, it is easy to show that the first is easily answered, at least for a marginal unit of capacity, and that the answers to the two questions then coincide. For I have decided to charge during the (infinite) useful lifetime of the addition to capacity a stream of prices given, according to (11.5), by pt = ∂c/∂xt + λt. The net gain from the marginal unit of output is then pt − ∂c/∂xt = λt. Hence the marginal value of a unit of capacity added in period t is (since the λ*t are all present values)

By the next period, the residual value of that piece of equipment will have fallen to (1 − k)vt + 1 = (1 − k)λt + 1 + (1 − k)2 λt + 2 + …. Consequently, the amount by which the value of the marginal unit of equipment will have declined in period t is precisely

in other words, it is exactly equal to the period t depreciation payment calculated in answer to the optimal depreciation problem. Thus, so long as the revenue requirement is met by prices given by (11.10), the two interpretations of depreciation turn out to be identical. Where, in addition, a revenue requirement must be imposed on the analysis, prices will presumably be different from long-run marginal costs, and so the two answers will no longer be identical.

Finally, I turn to the so-called myopic property of the solutions. This remarkable property, which Arrow (1964) attributes to earlier writers, applies in the special case where some R&D investment occurs in each of two successive periods, i.e., when yt > 0 and yt + 1 > 0. In that case, it is necessary to forecast only one single period in the future in order to determine the correct magnitude of depreciation or long-run marginal cost. Moreover, in that case, the depreciation figure can be determined simply from four data: (1) the R&D cost of an added unit of capacity in the current period, vt; (2) that of the next succeeding period, vt + 1; (3) the calculated rate of loss of physical productivity of the capacity, k, and (4) the discount rate, r. This follows at once from (11.6) and (11.7). From these I calculate immediately the long-run marginal cost figure

This is the correct long-run value of marginal cost, since it includes both the marginal operating cost and the period’s assigned contribution toward capacity replacement.

The rules given by (11.8), (11.10), or (11.10′) are called “myopic” because they permit depreciation of R&D investment to be calculated correctly with the aid of a forecast extending over only one period and not over the entire life of the added capacity. Moreover, they refer not to some average of one-year cost differences but to the actual difference in cost between this year and the next. For example, suppose that, because of technological progress, the costs of added capacity decline 5 percent per year on the average. However, this year happens to be particularly slow on innovation in R&D procedures, so that the expected R&D cost of added capacity is going down at a rate of only 2 percent. Then the latter is the correct figure to use in the myopic formulas for long-run marginal cost!

The reason the rules work has already implicitly been explained. If some R&D investment is going to have to take place next year in any event, the marginal cost of increased R&D today is simply the added cost of carrying it out one year earlier, all other decisions remaining unchanged. After that (say, in the third year), since the innovations provided by the R&D would have been in existence in any case, the only difference it makes if the R&D takes place today rather than next year is the one-year reduction, (1 − k), in its productivity. That is, in computing the marginal cost of its provision today, we perform the calculation

[total present and future cost of carrying it out today] minus [total present and future cost of doing so next year] plus [cost of replacing the portion that decays from this year to the next].

Since any associated third-year cost is already contained in each of the three terms in brackets, it simply cancels out in subtracting. All that remains after subtraction is the cost difference over the one-year period beginning today, clearly ∂g/∂yt − (1 − k)∂g/∂yt + 1, the right-hand side of equation (11.6).

The myopic decision rules can be helpful in practice because, where they apply, they can simplify the calculation of marginal costs and depreciation charges. Unfortunately, the conditions for their applicability are somewhat more demanding than they may seem at first glance. It is not enough for a firm as a whole to invest in R&D in every period. The products of the R&D in different years must all be substitutable for one another as additions to capacity, otherwise the argument does not work.

If this condition—the investment in new substitutable innovations each period—does not hold, the myopic depreciation rules (11.10) and (11.10′) need not be valid as they stand. In that case, we may have to employ instead conditions such as (11.3) in which all relevant future periods must be considered in the depreciation calculation.

WHAT HAS THIS CHAPTER ACCOMPLISHED?

The analysis just provided has illustrated how the analysis of routine innovation activity can be carried beyond the elementary level of the previous two chapters in theoretical analysis that answers the sorts of question that conventional value theory investigates. It has done this simply by using analysis taken directly from capital theory and transferring it to R&D activity. It has shown how the optimal time path of investment in R&D can be determined, considering both the social optimum and the profit-maximizing solution for the innovating firm. It has described how the process affects the pricing of the commodities in whose production the (process) innovations in question are utilized. It has indicated how one can analyze the effects of parameters such as rate of obsolescence and discount rate on the optimal intertemporal trajectories. Finally, it has examined how pricing and recoupment of the R&D outlays are interrelated.

Still, a good deal remains to be done. Most notably, the model deals with process rather than product innovations, and any theory of routine innovation that neglects the latter obviously is seriously incomplete. Perhaps even more important, the analysis of this chapter and that in the next is fundamentally static, incorporating nothing about the active competition of business firms that forces them to keep abreast of their rivals in their innovation efforts. As a result, the discussion here has told us only a little about innovation as the engine of capitalist growth, which is presumably the prime reason for increased attention to the mechanism of capitalist innovation and enhancement of its incorporation into the central economic theory.

However, there are a number of tasks that the static theory can carry out. It can explain such things as the timing of the introduction of an innovation into the market, that is, its emergence from the R&D laboratories, or the circumstances in which firms will select cooperation with other firms rather than rivalrous activity for some or all of their innovative activity. Some of this has already been discussed. The next chapter carries on with this process, turning to the optimal timing of innovation introduction.

___________

1. Such a model is, in fact, constructed in Baumol (1971). Most of this chapter is based on that article.

2. Where there are economies of scale in R&D investment, excess capacity may also occur in some periods because it is economical to anticipate growth in demand by means of large early investment outlays. With the premise of constant returns to scale this source of excess capacity is absent.

3. This assumes that there exists no price at which demand during this period will suffice to utilize the capacity fully and still more than cover the marginal operating cost.

4. Much of the material that follows is, essentially, a slight modification of Littlechild’s (1970) work.

5. Strictly speaking, this implies the absence of externalities of consumption. Note that I am dealing here not with an “absolute marginal utility” but with a marginal utility measured in money terms, i.e., with the marginal rate of substitution between x and money, which is, of course, equal to px/pm, where pm = 1 is the “price” of money.

6. It should also include marginal user cost, that is, wear and tear of capacity. However, because it adds no insights, user cost has been omitted from this chapter. It is included in the earlier article on which this discussion is based (Baumol, 1971).

7. This defines the period, so that the investment outlay, vt, is made at its beginning while the depreciation, μt, is collected at the end of the period. Consequently, to obtain the corresponding present values at the initial period t = 1, we divide the former by (1 + r)t − 1 and the latter by (1 + r)t.