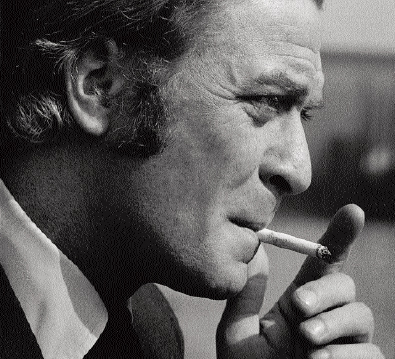

Michael Caine as vicious London gangster Jack Carter

“In the beginning is the end – but we still go on.” Samuel Beckett

Early in 1970, Michael Klinger, the producer of Roman Polanski’s first two British films, Repulsion and Cul-de-Sac, bought the film rights to Ted Lewis’s then-unpublished novel Jack’s Return Home, about a London racketeer who sets out to discover the cause of his brother’s sudden death. “Immediately I could see there was a film there,” recalled Klinger, who had realized he could exploit the recent upsurge of interest in the underworld aroused by the trial of the Richardson and Kray gangs. A close friend of Klinger’s, Robert Littman, was Head of European Production for MGM and looking for new projects. When the two got together to discuss Lewis’s novel, a deal was soon struck to make it into a hard-hitting, realistic gangster film.

Klinger had been thinking about Michael Caine in the role of Jack Carter, and the night after seeing Hodges’ Rumour on television, he called Caine’s agent, Dennis Selinger. The two men discussed both

“So calculatedly cool and soulless and nastily erotic that it seems to belong to a new era of virtuoso viciousness.”

Pauline Kael on Get Carter

the novel and how impressed they were by Hodges’ second TV film. When it was agreed that Hodges was to be approached to direct the adaptation of Lewis’s book, Selinger called Caine. Having also seen Rumour, Caine signed up: “One of the other reasons I wanted to do it was because I had this image on screen of a Cockney ersatz Errol Flynn. The Cockney bit was all right but the ersatz suggested I’m artificial, and the Errol Flynn tag misses the point. One’s appearance distracts people from one’s acting. Carter was real,” claims Caine.

Hodges had never adapted a novel to the screen before, and at first felt obliged to the author. He sent Lewis copies of the script as it evolved, making sure to keep the writer informed at every stage. “It was an extraordinary time for both of us,” says Hodges. “We were both moving into another, bigger league. I subsequently heard that Ted had been desperate to write the script himself. He was a lovely man and I had no idea at the time that he wanted to do it. That saddened me.”

The first page of Ted Lewis’s novel reads: “I was the only one in the compartment. My slip-ons were off. My feet were up. Penthouse was dead. I’d killed off the Standard twice. I had three nails left. Doncaster was forty minutes off.”

However, Hodges’ final script deviates straight away. While Caine’s Carter is still an obsessional man, he pops pills and certainly doesn’t bite his nails. He’s also a man who points and doesn’t say “please”, unlike the Carter in Lewis’s original novel.

Extract from Hodges’ screenplay:

Int. the long bar. Night

A couple of youths are playing records on the juke box. An old man sits in the corner reading a newspaper.

Carter enters through the swing door and a weedy barman comes to serve him. Carter: Pint of bitter.

The barman picks up a glass mug and begins to draw the beer. Carter snaps his fingers at him.

Carter: In a thin glass.

The barman sighs petulantly, transfers the beer into a thin glass and puts it on the counter.

Another deviation in Hodges’ script is the location. Lewis came from Scunthorpe and had written it with his home town in mind. In fact, in the book, Carter changes trains at Doncaster and heads for a town with no name. All we know is that it’s a steel town. The problem of where to set the film was solved when Hodges remembered his time in the National Service:

“On a minesweeper in the navy, I’d literally floated into every major fishing port in the British Isles. I told Klinger about the places I’d seen and off we trolled up the east coast in his Cadillac. Although the book wasn’t set anywhere specific, the landscape was a major player in the piece. It was important that Jack Carter came from a hard, deprived background, a place he never wanted to go back to.

There would have been no morality to this tale until you saw where he came from. When we got on the road I quickly realized that the east coast had changed radically since I’d been there in the early fifties. The only place that had survived the developers was Newcastle-upon-Tyne, but only just. We got there just in time. When I’d been in the navy I’d only been to North Shields, which was pretty grim, but this time I came by land which brought me to Newcastle. I fell in love with it as soon as I saw it. So that’s where I set it. An important decision that! I stayed on after Klinger and the Cadillac had left for London and began to fit all the extraordinary locations I found into the script. This gives just a feeling for the place. There was a massive club there called La Dolce Vita. Can you imagine that – a club in Newcastle in the late sixties named after a Fellini film?”

It turned out that La Dolce Vita had been the scene of a real-life murder three years before Hodges made Get Carter, aspects of which he decided to work into his script:

“The body of Angus Sibbet had been found under a railway bridge close to the La Dolce Vita. He’d been shot. Two men, Dennis Stafford and Michael Luvaglio, were arrested and convicted. It was the motive for this killing that provided much background detail in the film, as well as an important location – Cyril Kinnear’s home.

“Luvaglio was the youngest brother of Vincent Landa, a flamboyant entrepreneur who had lined his fruit machines with false bottoms, and then did a bunk with the swag to his villa in Majorca.

“Both Luvaglio and Angus Sibbet had been involved in extracting the money from the machines. Sibbet got greedy; end of story; end of Sibbet. It later transpired that a hit man, not unlike Carter, had probably gone to Newcastle and done the job, so the film’s story was not as far-fetched as it might have seemed at the time. I married this story to the novel, which enabled me to give it a lot of texture. I’m not trying to say the book wasn’t good in the first place – I thought it was terrific – but I was trying to give it yet another layer.

“It’s ironic that Dryderdale Hall, previously the residence of Vincent Landa, should become the fictional home of the film’s arch villain, Cyril Kinnear. It was a very spooky place; no one had wanted to buy it, so we were able to use it. And we had to do very little to make it convincing. It was the real thing.”

While searching for the locations Hodges was also thinking about a cinematographer. Dusty Miller had lit and operated Rumour but Klinger was nervous as Miller had never shot a feature film. Hodges then remembered seeing Ken Hughes’ film The Small World of Sammy Lee (1963):

“It’s a film that’s been lost somewhere down the line. It starred Anthony Newley and Wilfred Brambell and, although I only saw it once, I remember being very impressed by it. So when I was asked to make Get Carter, I sought out the cameraman, Wolfgang Suschitsky, who had shot the film in black and white. He agreed to do it and Dusty generously agreed to be the operator. I’m not sure why that film stuck in my memory. Sammy Lee was a runt of a character, nothing like Jack Carter. But I remembered it had a kind of urgency and sleaziness. It was all shot in Soho. Ken Hughes is, in my opinion, a very under-estimated director and at the time I was a great fan of Anthony Newley.

“Obviously, while you want each of your films to be an original, it’s impossible not to be influenced by films you’ve seen. As well as The Small World of Sammy Lee I really liked Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock (1947). Most of the other British crime films I’d seen weren’t very impressive. They were unrealistic, soft. I wanted Carter to capture the ruthless viciousness revealed when the Krays and the Richardsons were finally brought to court. I wanted to be as honest as I could be with the original material but in fact ended up making a film much harder than the book.”

Caine agrees with Hodges that making Get Carter was a chance to show gangsters as they really are and says he took the role of Jack Carter because he wanted to star in a truthful gangster picture: “I mean, compared with Texas Chainsaw Massacre it was Mary Poppins. But what was violent about it, was that the people were real. And so you believed the violence.” Caine, of course, originates from the Elephant and Castle area of South London, which was, in his words, “a very rough district”. With Get Carter, he liked the idea of telling it like it was:

“I’d always seen on screen, in British pictures, not American ones, gangsters were either stupid or very funny or Robin Hood types, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. And I knew that none of these portraits were true. They weren’t stupid and they were definitely not funny, they were very serious. Hodges knew that as well. He is a wonderful director because he takes things of the moment and if something is there that he can use, he’ll use it. He’s not rigid and all the best directors are never rigid. He was great. He came up with all sorts of new ideas once we’d got on location.”

Until then Hodges had used mostly unknown actors in his films. “As I was also the producer no one ever asked me about the cast.

“Caine is Carter” film poster

They weren’t obsessed with names like they are now. It was incredible. I was left completely to my own devices.” Caine was the first film star he had encountered: was the advertising slogan, and it was right. He was Jack Carter. Like most actors established in the 1960s who came from his background, he knew this character backwards. Everything he did was dead accurate. I’d always seen Carter as a little seedier myself, but Michael simply stalked through it, sharp as the Kray twins. He left the seediness to the people around him. And luckily for me, when we got to shooting, Michael was far more relaxed than other stars. He didn’t expect to have a close-up in every scene. Many stars would have been very pissed off with the way I went about this film. But he knew he was in every single scene and was savvy enough to realize that we didn’t need the traditional kind of coverage. In fact, in a lot of shots, I found myself shooting whole sections on his back.

“When I was rehearsing my first scene with him, and this will sound naïve, it suddenly dawned on me the difference between working with ordinary actors and a star. I was looking through the camera as he strode up the long bar to take the phone call from Margaret. His head filled the screen, and I realized I was in a completely different ball game. It wasn’t to do with realism any longer, it was something else and I’m not sure I knew what it was – except that it was exciting.”

Caine as Carter set a precedent for the ultimate hard man – gangsters have never been cooler or colder

Klinger and Hodges’ instincts were right. Caine delivered a truly magnetic performance. His gripping portrayal of the hard-man hero out to avenge the recent murder of his brother is terrifying. He never forces a line, is completely confident and his calm, measured rhythms are ideally suited to the role. As Caine himself said at the time:

“Carter is a subtle combination of private eye and ruthless gangster. It’s the strongest, most fascinating character I’ve played since Alfie. I modelled Carter on an actual hard case. I watched everything he did and once saw him put someone in hospital for 18 months. These guys are very polite but they act right out of the blue. They’re not conversationalists about violence, they’re perfectionists.”

When it came to casting the rest of the film, MGM wanted to fill the screen with star names. This was not the way Hodges was used to working. He wanted to surround his star with believable characters and could see all of his attempts at creating a realistic thriller flying out of the window.

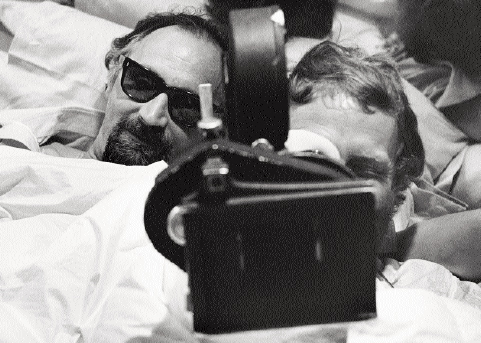

Hodges with camera operator Dusty Miller. They are lining up a shot of Carter watching a porn film from the bed

“I thought that now we had a star on board I could complete the casting with actors of my choice. But to my astonishment, MGM

“It’s totally to do with instinct. You can smell a good actor. I rarely ask them to read. I just sit and talk with them, sometimes for a long, long time.”

Mike Hodges

kept coming up with these awful ideas such as Telly Savalas for the part of Cliff Brumby! They wanted ‘names’ even in the small characters. Personally I can’t bear watching films with an audience waiting for the next big entrance and I fought hard not to let it happen here. I simply threatened to resign every time one of these ridiculous suggestions was made. In the end the only names we had on the marquee were Michael Caine and Britt Ekland who we cast as Carter’s mistress. Britt solved the problem. Her name kept the producers happy, even if her role wasn’t that big.”

Another inspired piece of casting by Hodges and Irene Lamb, his casting director, was Ian Hendry. Hendry played the small but important role of Eric Paice, the seedy chauffeur to gang boss Cyril Kinnear (John Osborne). A decade earlier Hendry had been a much bigger name than Caine but by 1970 his career had waned, the result of bad choices, bad luck and a severe drink problem:

“Ian was a very heavy drinker and was really quite ill. I actually thought he was going to die on Carter during the chase sequence at the end of the film. His career was in tatters and he was extremely jealous of Caine. Ian was a terrific actor but simply wasn’t destined to stay at the top whereas Michael obviously was. Maybe he didn’t have the sex appeal? Maybe he simply wasn’t dedicated enough to the idea of being a star? On the other hand Michael knew exactly how to go about becoming one and staying up there. When Ian arrived in Newcastle, I suggested we rehearse the racecourse scene where he meets Carter for the first time. He arrived at Michael’s suite in the hotel completely pissed. It was chaos and so vitriolic. Michael handled the whole situation wonderfully. With Ian being abusive to him I just said, ‘Forget it’. The next day, when they played the scene, it was just perfect. Inadvertently, I’d done the right thing because the clash between them has really got an edge to it. And it was meant.”

The most difficult character to cast, according to Hodges, was Kinnear, the local godfather who, in Lewis’s novel, was described as “very, very fat … the kind of man that fat men like to stand next to. He had no hair and a handlebar moustache that made his face look a foot long on each side … He was also only five foot two inches tall.” Again Hodges was determined to go his own way and persuaded Michael Klinger to accept the writer John Osborne in the role. Osborne’s controversial play Look Back in Anger had helped break down the conservative status quo in the mid-1950s. He had started as an actor and since his first play had written many major works for both theatre and cinema. However, unlike Kinnear in the novel, he was tall, slim and bearded.

In choosing the rest of the cast Hodges had his way, surrounding Caine with unknowns. He was back on his usual course:

“It’s like a painter filling his canvas with characters. It’s totally to do with instinct. You can smell a good actor. I rarely ask them to read. I just sit and talk with them, sometimes for a long, long time. I’ve noticed that American producers get terribly nervous when

“I like to feel free of any preconceptions when I arrive on a set or location. I love flying from the seat of my pants. It’s instinct again. There is just one moment when a scene comes together and, if you’re relaxed enough as a filmmaker, you hope you will recognize it.” Mike Hodges

they find out I don’t do camera tests. Well, I’m paid for my instinct so that’s what I rely on. Unfortunately some producers try to destroy your instinct, which begs the question of why on earth they employed you in the first place. Trouble is a lot of producers have no vision, no idea what they really want!”

Hodges used storyboards for complicated optical effects in Flash Gordon (1980) and the detailed surgical operation in The Terminal Man (1974), but in general hates the idea of using them:

“I like to feel free of any preconceptions when I arrive on a set or location. I love flying from the seat of my pants. It’s instinct again. There is just one moment when a scene comes together and, if you’re relaxed enough as a filmmaker, you hope you will recognize it. The worst thing you can do as a director is lay awake all night worrying about how you’re going to shoot a scene, planning a complicated tracking shot or whatever, only to get on the set the next morning and realize there are three pillars and a sofa in the way! Better to sleep and arrive fresh. Hopefully that freshness will rub off on the scene.

“I like to retain the same sense of freedom with the sounds and music in my films. A sound man will always have his ears open for interesting sounds while we’re on location. I always encourage this. Sounds, often unusual ones, can transform a scene. I love it when the sound editor offers you a selection of different, even surreal ones. Jim Atkinson, the sound editor on Get Carter was brilliant. Next time you see it listen for the little bells on the telephone sex scene. And when Jack knifes Albert Swift, listen for the distant ship’s horn. It’s a sad, soulful sound, like a dying elephant. It replaces Albert’s last gasp.

“Sound tracks these days are too cluttered and noisy and there’s far too much music. It always shows a director’s insecurity. Actually it’s more likely the producer who is nervous. Silence can make people very insecure. I have a theory that contemporary films have to be loud so audiences can’t hear themselves eating.”

Hodges soon discovered the importance of the first rushes that the studio executives see. If they’re good, preferably sexy, they will feel secure and hopefully leave you alone, free of asinine suggestions. In the case of Get Carter he was lucky. The very first material they saw was the movie-within-the-movie footage. It was a porn movie. They loved it:

“The first material coming in from any film shoot is inevitably a surprise to film producers and financiers. It’s rarely what they expect because it’s hard, if not impossible, to visualize what it’s actually going to look like. If they’re disappointed you’ve got problems from the off. With Carter I had the perfect lift-off. The pivotal moment in Carter is when Jack sees the porn film featuring his niece Doreen. Because I needed it for the actual scene I shot it in London before leaving for Newcastle. So – the first footage they ever saw was this tacky porn simulation. Perfect! They knew they were on to a winner. That says a lot about them, doesn’t it? It’s very important what you show these money men first.

“But it was embarrassing shooting it. We arrived at this prop man’s house, where we were shooting it, a terraced house somewhere. There were three actresses, one actor and me. I had no idea how to start so we all sat in the lounge looking at each other. What made matters worse was the prop man’s Alsatian had a big suppurating ulcer on its back and kept coming into the room. The whole experience was horrible. I had brought some champagne as a possible primer but funked producing it. Then one actress looked over at the small bar and says, ‘I think I could do with a sherry.’ So they all had a glass of this disgusting South African sherry and that did the trick. We started and it was finished in a couple of hours. It was my first and last pornographic film.”

His first outing as director on a feature, Hodges impressed all concerned and ended up scripting, casting, directing and editing the entire movie, within its $750,000 budget, in just eight months.

Set in Newcastle c. 1970 in a world of gangland brutality, sex and corruption, Hodges begins as he means to go on, with a brilliant dreamy opening sequence, full of symbolism, which has Carter framed in a large picture window, up high in a penthouse apartment, alone, looking out at the night. There’s hardly any light and already the viewer can sense death in the air. He turns away as the heavy satin curtains close, wiping him from view. His fate is sealed from the outset.

Next, in the opening credit sequence, Carter is on the train, reading a Raymond Chandler paperback, on his way to Newcastle for his brother Frank’s funeral. It is only after watching the film a second time that some people will realize that Carter’s eventual killer is sitting in the corner of the same carriage with him, already on his tail. The paperback is Farewell, My Lovely.

Similarly, in a later scene set in a bingo hall, there’s another one of Hodges’ asides, in which he can’t resist commenting on where the film is going. This time, as Carter walks into the hall, most of a management disclaimer notice above his head is obscured. All the lettering is excluded from the shot, apart from the words “The Game Is Final”.

Get Carter is filled with these subtle touches and attention to detail: “I don’t think anything should be stated obviously. I have always been obsessed by the detail in pictures,” Hodges confesses.

The north-eastern setting is chillingly evoked. Although Carter has whisked himself away from his own soulless London surroundings, this city is equally drab and impersonal. As well as the grimy bingo hall, we see a world of seedy pubs, dingy local dance halls, dodgy boarding houses and grim back streets full of run-down row houses. The gangster film imagery is always present, from the sinister conveyer belt of black funeral cars pulling away as the family arrive for Frank’s funeral, to the sudden explosions of violence as ugly as violence really is.

It doesn’t take long for Jack Carter to suspect that his brother’s death wasn’t an accident and he sets out with ruthless efficiency to find the man who ordered his execution. Shotgun in hand, he follows a seemingly never-ending trail of lies to find those responsible, uncovering a cesspool of corruption that’s even tainted his innocent young niece (Petra Markham). Knowing the local criminal world, Carter looks around the racetrack and finds Cyril Paice (Hendry) a small-timer dressed up as a chauffeur. Following this trail brings him to a country house full of crooks headed by Roy Kinnear (Osborne). Although Carter is surprised to find himself more than welcome, he leaves with a warning to return to London before he causes any trouble. He ignores the warning and continues on his path of vengeance. With Carter now a loose cannon, a contract is put on his life.

The shock ending is classic Hodges. Carter, having gleefully dispatched his brother’s killer via a coal chute into the North Sea, strolls triumphantly along the sea front. He stops, looks at his shotgun, and decides to get rid of it. High on the cliff top a rifle and telescopic lens line up on him. A finger curls around the trigger. As Carter goes to throw the murder weapon into the water, a shot rings out. Cue the waves gently lapping at Carter’s lifeless body. This final sequence was shot on an overcast, murky day, making the event all the more bleak.

With its uncompromising violence and relentlessly grim atmosphere Get Carter was a sharp reflection of 1970s Britain, rife with industrial malaise and a world away from the fluffy 1960s. It was the gangster film that gave the genre a virulent dose of unremittingly bleak realism. In Newcastle Hodges had sensed the sickly smell of corruption that permeated the city. Without turning the film into a political statement, the social comment is there. Carter has become a criminal in order to live anywhere but the “crap house” where he was born. Newcastle is caught in transition, a city on the cusp, one that is going to be irredeemably changed. The urban tenements are in the process of being replaced by cold, inefficient high-rise tower-block developments, funded by increasingly business-like crooks, men like Brumby. Not to mention the behind-closed-doors dealings of powerful drug-pedlars like Kinnear. Maybe Get Carter has survived and is more popular than ever because the film now fits more comfortably with the British people’s view of their homeland?

Hodges and crew on the streets of Newcastle

“During my time in the navy and on World in Action I had a good look at the underbelly of Britain. I realized that despite the heritage image we liked to project it was as corrupt as any other country. Beneath the thatched image things were pretty rotten. Now, of course, it’s there for all to see. There’s no escape from it now but then there was. Once I’d decided to make Carter, I had to do it with the same ruthlessness as a surgeon opening up a cancer patient.

“I’m surprisingly sentimental about certain places in my life. For instance I find it painful going back to places I grew up in, particularly Salisbury, where I spent my childhood. Painful because they’ve changed almost out of recognition. Of course, most people living there are newcomers and unaware of this. But I am. And it’s the same with Britain. I really should live somewhere else because watching what’s happening here is too painful and it affects me badly. If I didn’t care, or thought the changes were for the better, it wouldn’t matter. But I do and they aren’t.

“In Carter we see Brumby talking about his new restaurant, what it’s going to be like. You’ve already seen his home so you know it’s going to be shit. The man has no taste but he has money. That’s the biggest change in this country. Pig ignorance and money are a lethal cocktail. Brumby represented, even then, the new Brit soon to come off the assembly line. Even the word ‘Brit’ is ugly!

“Interestingly, years after Get Carter I was asked to direct the BBC drama serial Our Friends in the North. I turned it down because in a way I was too obvious a choice. It was territory I’d already visited. At the time it occurred to me that Carter had caught the flavour of what was actually going on in Newcastle. It was only some years later that the extent of the corruption was finally exposed. I must have smelt it even then. Corruption does have a smell.”

Hodges launched Carter into a world of sleaze, sex and decadence and succeeded in producing one of the finest and hardest-hitting portrayals of violence and corruption ever made. One year later, MGM remade it as a black exploitation movie set in LA. Hit Man (1972) starred Bernie Casey as the revenge-bent gunman trying to find out who killed his brother. But this remake had a happier ending, with the lead character narrowly escaping death at the end of the film.

A few years ago Hodges thought about doing another Carter film himself:

“I did write a synopsis but not based on any of the Ted Lewis novels. With Jack Carter dead I fantasized that he’d impregnated Anna. The boy is adopted by God-fearing parents who knew nothing of his genetic history. It was about the painful confusion of both the adoptive parents and the child now as psychotic and violent as his father. I wanted to journey with the young Jack as he discovers the facts of his father’s life. Is he trapped in a genetic prison and, if he is, can he escape? I’ve recently read John Pearson’s second book on the Kray twins, The Cult of Violence. It’s brilliant and one can understand and even sympathize with the genetic trap they were in. I sent the treatment to Warner Bros. who own the rights to Carter. Needless to say it was rejected. A remake with Stallone was already in the works but I didn’t know it.”

In 2000 Sylvester Stallone starred in Stephen Kay’s completely watered-down version. It also had Michael Caine cast in the supporting role of Cliff Brumby (originally played by Bryan Mosley), and he got to be on the other side of his most famous line from the original film: “You’re a big man, but you’re out of shape. With me it’s a full time job. Now behave yourself.” Not surprisingly, however, Stallone’s remake drew terrible reviews and bombed at the box office. In fact, critics were not even given a chance to attend preview screenings, which meant that the weekly entertainment guides around the US had no chance to warn cinema-goers just how bad the movie was. Later, however, in a review that appeared in the New York Times, Elvis Mitchell wrote: “It’s so minimally plotted that not only does it lack context and subtext but it also may be the world’s first movie without even a text.” He reported audience members filing out within half an hour of the film starting. Hodges obviously expressed his disappointment: “I don’t know why they decided to remake it. For the amount of money spent on it they could have made plenty of original films. Remakes signal death of the imagination. I just wish they hadn’t used the same title.”

It does seem crazy that such a numbing mishmash of a movie can get made. The only positive aspect of the whole affair is that, hopefully, reviewers will have pointed out how much better the original film is and drawn Hodges’ Get Carter to the attention of a new generation of filmgoers.

Looking at the film now, more than 30 years on, it’s noticeable how it hasn’t dated at all. Through the clever use of costumes by designer Vangie Harrison, Get Carter will always look contemporary. And it will always remain cool, thanks to Caine’s performance, Roy Budd’s minimalist soundtrack, and Hodges’ direction.

A seminal British thriller, Get Carter redefined the genre for British moviemakers. Its influence on British filmmaking can be seen from The Long Good Friday (1981) to recent Brit flicks such as Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1999), Snatch (2000), Face (1997), Gangster No 1 (2000) and Love, Honour and Obey (2000).

The film industry’s current man of the moment, Guy Ritchie, says he made Lock, Stock and Snatch because he felt nothing much had been done with the genre in the UK for a long time, and he thought he could exploit it to make a name for himself. But even though Ritchie claims he’s not a fan of most British gangster films, he does have a soft spot for Get Carter. “It was stylish, it had an identity – Michael Caine at his best,” he says. “It was a grown-up film. My favourite bit in the film was when Caine was coming out naked with a shotgun and a northern military band was going by outside – he didn’t give a toss. It was one of those quirky, good scenes.”

Get Carter was the original – and the best – British gangster movie. A truly great film is one that stands the test of time and can still touch people long after the hype is gone. Get Carter was recently named the 16th top British film of all time in a BFI poll. It was also voted the best British film of all time by Hotdog magazine and hailed as a timeless classic by Loaded magazine, which serialized the movie in cartoon form. Loaded’s celebration of Get Carter was one of the main factors which helped push the main character of the film back to the centre of attention in the 1990s, although Hodges was not overjoyed that Jack Carter has became an icon of “Lad culture”: “I absolutely loathe it and who wouldn’t? I hate Lad culture. It’s a mindless macho culture with neo-fascist undertones. They even have the uniforms. Do we really want to live in a world filled with male slobs?”

On its initial release Get Carter received very mixed reviews with many critics denouncing its violence. Felix Barker of The Evening News described Hodges’ film as “a succession of gratuitously sadistic and titillating scenes”, and Cecil Wilson of the Daily Mail asked, “Did it have to be quite so gratuitously brutal?” But in the Daily Express, Ian Christie wrote: “The result is a tremendously exciting thriller that gives Michael Caine the best part he has had in years. Carter, you will gather, is not a nice person to know … It is a cruel, vicious film, even allowing for its moments of humour, but completely compelling nevertheless. I’d get Carter if I were you. It certainly got me.”

Get Carter shocked audiences in 1971 and still carries an 18 certificate today. Although recently revered as the ultimate celebration of cool 1970s’ machismo, an expression of cold British laddish values, to reclaim the film in this way is to miss the point. It is possible that Get Carter still frightens people, not because there is blood and gore or much in-your-face physical violence, but because of the underlying themes. Viewers may be frightened to look beyond the punch-ups and phone sex.

Get Carter certainly is a great film, and can obviously be enjoyed as a piece of entertainment but it is also a film which reeks of despair, emptiness and death. Some critics view it as an urban western, with Caine as the stranger riding into town, loaded with his own private anger and out for revenge. But Get Carter is closer to the Jacobean revenge drama, with the Caine character more reminiscent of the Mifune character in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) or the unstoppable, incorruptible samurai leader in Seven Samurai (1954). The Caine character is implacable and elemental, like Vindici in Middleton’s revenge drama Revengers Tragedy, and in the end he has to die.

As in Hodges’ earlier television dramas, death is ever present. Carter’s quest leaves a litter of corpses. But then, if there is one key underlying theme throughout the films of Mike Hodges, it is both the certainty – and uncertainty – of death. Later in his career came the deeply unsettling The Terminal Man (1974), about a computer scientist (George Segal) who becomes homicidal during periodic blackouts. In the acclaimed Black Rainbow (1990) Hodges explores not only death but the idea of a constant recycling of the life force; and in the more recent Croupier (1998) we are reminded of how life and death are as much to do with chance as anything else. Films as dark as this don’t often make it into the mainstream movie circuit. But perhaps viewers are afraid to participate in Hodges’ observations on the randomness of the world and the lives of its inhabitants.

Unlike Villain (1971) and The Krays (1990), Hodges’ Get Carter isn’t a formulaic, studio-style picture made by committees. It is a superbly structured revenge thriller that was written and directed by one man. An auteur film, it was undoubtedly way ahead of its time and will easily survive beyond the ironic appreciation of the Loaded generation. As Jack Carter, Michael Caine was a cold, brutal and methodical assassin – a world away from the average macho British “lad”. At the moment, current hip gangster films such as Lock, Stock and Face offer nothing more than pure entertainment with no social detail. They are farces, something to laugh at. Hodges’ groundbreaking classic, however, will always be a film to be taken seriously.