Chapter 2

‘Come on, boys, we are making history’

1–4 August 1916

At the start of August 1916, both light horse brigades at Romani had temporary commanders. Lieutenant Colonel John Meredith took over the command of the 1st Brigade after General Cox fell ill and was sent on leave to England. Johnny Meredith, as the troopers called him, got off to a bad start when he led the brigade astray on the night of 31 July, ‘much to the disgust of the lads who were not at all pleased with the concern’.1

At the time, General Ryrie was in England, on leave of absence related to his standing as an Australian politician. In Ryrie’s absence, Colonel Jack Royston, the commander of the 12th Light Horse, was appointed to temporary command of the 2nd Brigade. Royston was a South African who had served in the Boer War and in German West Africa in the current war. Both new commanders had dominating sand hills east of Romani named after them.

On 19 July, a Turkish advance on Katia was spotted from the air. That night, light horse patrols fired at Turkish forces near Oghratina and some prisoners were taken from the Egypt Expeditionary Force, which comprised 20,000 troops under the command of the German General Friedrich Kress von Kressenstein. The ‘picturesque ruffian’, Djemal Pasha, was the nominal commander-in-chief.2 The troops were backed up by some 2500 Austro-Hungarians and Germans serving six heavy batteries of Austro-Hungarian and German artillery, plus the German 605th Machine Gun Company.

The 605th, led by Lieutenant Benkwitz with 31 men, had departed Berlin by train on 29 March 1916, reaching Constantinople on 7 April before crossing the Bosphorus and reaching Semakh on the Sea of Galilee in early June. Here the company incorporated 67 Turkish ranks and began working with camels and carrying out field firing tests. On 22 July, the company saw its first action when the machine-gunners opened fire on a British plane at Bir el Abd.3

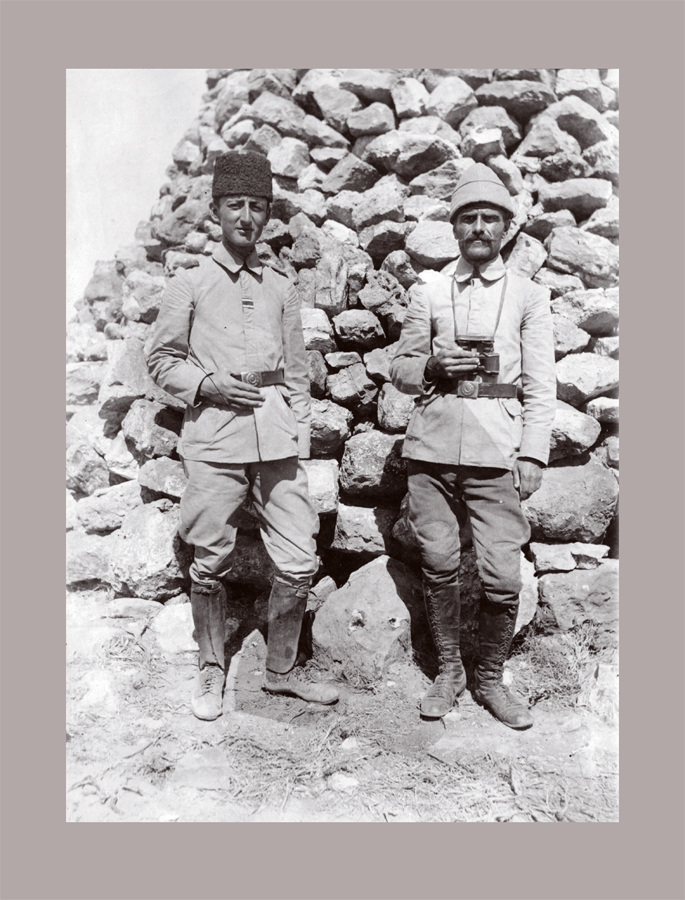

Colonel Jack Royston at Dueidar in mid-1916. This photo was taken while he was in command of the 12th Light Horse before Romani. George Francis collection.

Most of the Turkish troops were from the veteran 3rd Division. Manned by Anatolian troops, this division had performed well at Gallipoli and in the earlier attack on the yeomanry at Katia. The Turkish force was some 160 kilometres from the nearest railhead and relied for supply mainly on limited camel trains, 18,000 of which would be employed on this operation. There were only a few mounted camel troops to provide any mobility to rival the manoeuvrability of the light horse.

Nevertheless, the Turkish force had very good artillery support, and this could prove critical. The aim of the operation was to advance to within artillery range of the Suez Canal and thus close the vital waterway to shipping. Wooden planks or lined furrows were required to move the artillery pieces across the sand. The attack would be made in the heat of summer, but to wait for cooler weather would have exacerbated the water problem. Unlike the Allied force, the Turkish troops were forced to drink the brackish water from the desert oases to survive. All movement was by night, led by Bedouin scouts, the days spent sheltering under palm groves. Oghratina was reached without incident.

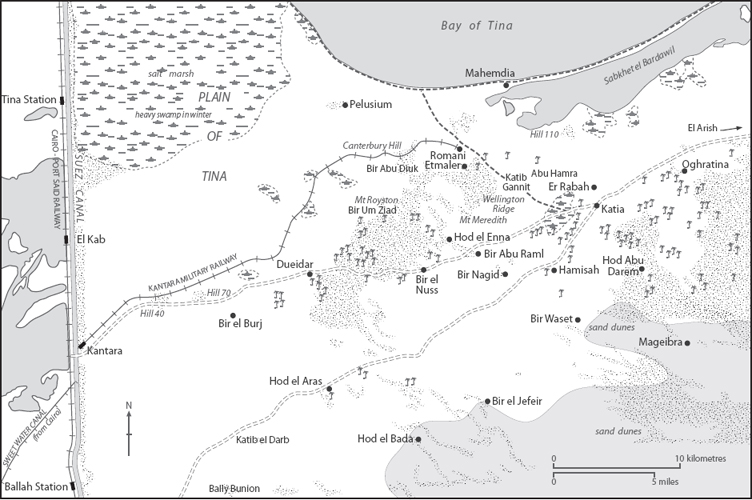

Map 2: Sinai desert

A Turkish camel train loading ammunition. George Francis collection.

Major Carl Mühlmann, serving as a German staff officer with von Kressenstein, noted that ‘surprise and swiftness of execution were essential to success’. As soon as darkness fell on 3 August, the Turkish left wing advanced, aiming to outflank the Romani defences to the south before turning north to come in behind the main infantry defences in Romani. Mühlmann wrote that ‘the hours of the night sped by’.4

The light horsemen knew the Turks were coming. General Chauvel later wrote that ‘it was evident that the long threatened second attack on the Suez Canal was about to be launched’.5 On 22 July, Captain Harold Mulder wrote, ‘the whole of the Turkish 3rd Division led by a German general and with German machine gunners are there . . . I guess we’ll smash the whole lot up.’6 Starting on 20 July, the 1st and 2nd Brigades patrolled out from Romani on alternate days, returning at midnight but leaving out small mobile listening posts overnight. Gordon Macrae, who was with the 6th Light Horse, wrote, ‘we have been going solid all week. Every alternate day we go out to meet Jacko [the Turks].’7 The New Zealand brigade, later joined by the 3rd Brigade, patrolled the Mageibra area on the right flank. Both sides manoeuvred their forces for the coming clash.

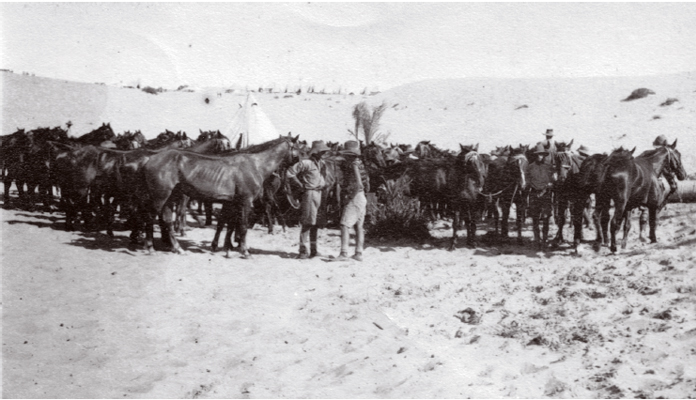

The 6th Light Horse on the march. Ralph Kellett collection.

On 26 July, Maurie Pearce wrote, ‘The opinion of the heads appears to be that the Turks are preparing for a big attack on the Suez Canal . . . we are ready for them and for a spell after we have towelled them up.’ Pearce got his fight on 29 July, when a troop from the 1st Light Horse on outpost duty at Katia was outflanked and nearly surrounded by the Turks. ‘Bullets were very thick round us,’ Pearce wrote, but ‘luckily the Turks overestimated the range and the bullets went high, otherwise few of us would have got away . . . Long, Roper and Rinaldi were hit and a few horses, one [of which] had to be shot.’8

The commander of the Imperial force, Lieutenant General Sir Herbert Lawrence, had been ordered to hold Romani and draw in the Turks, but he also had concerns about his open right flank. Lawrence had four infantry brigades and five artillery batteries defending his supply base at Romani, with the Anzac Mounted Division out in front and covering the right flank. Another infantry division was gathering at Kantara, while two naval monitors had anchored off Oghratina to shell any enemy troop concentrations there. Lawrence’s major weakness was his own location; he was content to control the battle from his headquarters at Kantara, despite General Murray urging him forward.

The 1st Light Horse camp at Romani. Royal New South Wales Lancers Memorial Museum collection.

A camel train. Edwin Mulford collection.

Jeff Holmes, who was a horse team driver with the engineers of the 1st Field Squadron, watched the build-up at Romani. ‘Trains of camels have been passing for the last few days but the longest of all passed today,’ he wrote on 26 July. ‘There were two thousand camels, nearly 5 miles in length and it took nearly two hours to pass by.’9

On 2 August, a Turkish deserter of Bosnian origin from the 3rd Turkish Division gave himself up at No. 8 Post at Romani. He told his captors that about 19,000 Turkish troops were advancing on Katia and Romani.10 On the morning of 3 August, the first Turkish forces entered the Katia area, with more to the south-east. The deep wells at Katia were vital for any further advance. Bill Peterson wrote, ‘Jacko is having the time of his life since occupying Qatia. He won’t have a leg to stand on soon.’11 Later in the afternoon, Peterson was sent up onto Mount Meredith to lay a phone line and was kept busy that night repairing breaks caused by passing horsemen. At 10 p.m. the first reports of gunfire came in from the outpost line and by 11 p.m. the firing had increased.

General Chauvel ordered Lieutenant Colonel Meredith’s 1st Brigade to occupy the high sand dunes forward of Romani. Lieutenant Colonel David Fulton’s 3rd Light Horse was on the left, from the infantry outpost to Mount Meredith, while Lieutenant Colonel George Bourne’s 2nd Light Horse stretched south from Mount Meredith to Hod el Enna, with the 1st Light Horse in reserve at Romani. The light horsemen established the outpost line just after dusk and then waited.12 Major Mick Bruxner, who was from the same fertile lands of the Upper Clarence Valley in northern New South Wales as General Chauvel, was a squadron commander with the 6th Light Horse. He later wrote of ‘the tiny Cossack posts of 4 or 5 men, camouflaged behind a dune amongst the bushes’, far out in front of ‘the remainder of the troop sleeping, perhaps many of them their last earthly sleep, like tired giants . . . in a little hollow are the patient horses’.13

Just before midnight, a force of some 500 Turks was spotted near Hod el Enna, and Meredith’s regiment was brought up to cover the left flank. The Turkish plan had been to follow the 2nd Brigade back to Romani. Out with the 1st Brigade’s machine-gun squadron, Gordon Cooper heard the first shots fifteen minutes before midnight.14 As Bruxner wrote, ‘up and down the line comes the crackle, crackle of rifle fire and the rip-rip-rip of machine guns. This is only a feeler by John Turk.’ But by 1 a.m., ‘up steep slopes comes the Turk infantry, withering away under our steady fire, but always coming swiftly on’.15 Charles Livingstone, also with the 6th, wrote, ‘When I felt liquid running down my leg I thought I had been hit too, but the bullet went right through my water bottle and hit the leg of the man behind me.’16

Around 1 a.m. on 4 August, the Turks attacked the outpost line out of the darkness, and under a heavy exchange of fire crept closer in. Then at about 2.30 a.m. they ‘charged with fixed bayonets yelling allah, allah’.17 ‘Light Horse on Meredith Hill hard pressed urgently require reinforcements,’ Bill Peterson wrote. ‘Every available man up in the firing line most of my signallers are there.’18 The 1st Light Horse moved from reserve up onto Mount Meredith but, as Peterson related, the position could not be held. ‘Turks have charged with the bayonet and have taken Meredith Hill, which makes our position untenable now,’ he wrote. ‘The only thing to do is to withdraw to safer ground.’ Peterson gave his report to Colonel Royston, who galloped off as the Turks pressed their attack. ‘I hear the Turks yelling cursing and shouting and before we realised what had happened they pour over the ridge about 50 yards from us firing for all they are worth point blank,’ Peterson wrote. ‘Then a mad scramble for our horses . . . the bullets were like hailstones.’19

After two 3rd Light Horse outposts were overrun, Major Michael Shanahan found four horseless men. He got two up on the horse and with the other two hanging onto the stirrups, his mighty steed carried all five men to safety. The light horsemen held onto the wall of sand that was Mount Meredith until flanking moves forced its abandonment around 3 a.m. On the right, Shanahan’s squadron took heavy casualties from Turkish flanking fire and also withdrew. As the retiring units reached their second line, the order rang out: ‘Sections about—Action front!’20

Trenches at Romani. Arthur Reynolds collection.

Sapper John Hobbs, a signaller with the 1st Brigade, was hunkered down only 10 metres behind the firing line and under very heavy fire. ‘The enemy poured rifle and machine-gun fire on us,’ he wrote. ‘I cast a hasty glance round and saw three of our boys being dragged out by the arms and legs.’ ‘Allah, allah, finish Australia,’ came the cry from the Turks. The brigade held out for three hours ‘until it was impossible for human flesh to stand more’. Hobbs took a wounded man back on his horse, which he led over a machine-gun-swept ridge. ‘I was horribly scared and could hardly stand when we got in,’ he wrote.21

Fred Tomlins, who was with the 1st Light Horse, got the alarm at midnight. ‘Our outposts were retiring and fighting their way back,’ he wrote. ‘We rode up close to the Turks, dismounted for action and were soon in the thick of it just at dawn,’ he continued. ‘The Turks were coming up the gully in hundreds and the closest were within 100 yards of us when we opened fire and they charged yelling Allah Allah, but again Allah deserted them and they fell thick and fast.’22

Turkish dead in the Romani sand below one of the dominating sand ridges. When later buried, many were found stripped naked with not even an identity disc. ‘That was Bedouin work,’ the official historian wrote. Hugh Poate collection. Courtesy of Jim Poate.

Lloyd Corliss was also with the 1st Light Horse. ‘The retreat was a lively one and we were all mixed up and no unit of the First Regt was kept together,’ he wrote. ‘The enemy fired many shells and done some very good shooting.’23 Frank Willis was another 1st Light Horseman. On the previous day he had found time to write home: ‘We are hard at it here at last and have had a few quite exciting little adventures lately.’ Back at his family property at Crookwell in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Willis’s beloved dog howled throughout the night. The next morning the dog was missing, never to be seen again. By then Frank Willis lay dead on the Romani sand. He had survived the retreat and was refilling his water bottle from a water tank behind a sand bank when a stray bullet struck him in the head.24

At 4.20 a.m. the 2nd Brigade moved up on the right flank of the battered 1st. The 6th and 7th Light Horse occupied Wellington Ridge alongside Lieutenant Colonel William Meldrum’s Wellington Mounted Rifles, which had been attached. At about the same time the Turkish guns opened up. The fighting continued until ‘that fatal tinge of dawn and with it the bark of a mountain gun and the whine of the shell followed by the white puff as the shrapnel bursts over the stubborn line’.25

At 7.00 a.m. the Wellingtons covered the withdrawal of the 6th and 7th Light Horsemen from Wellington Ridge. The ridge was swept by shrapnel, machine-gun and rifle fire. ‘The Turks have a terrible lot of machine guns,’ Robert Farnes wrote.26 Squadrons moved back in steps one at a time under covering fire, leaving none of the 80 or so wounded men behind.27 ‘Wounded come straggling in, pale, bloodstained men with the cheery smile still on their lips,’ one of the light horsemen wrote. ‘“Pretty warm up there, boys,” they remark.’28 ‘All of a sudden bullets began to whiz around, then we all took shelter,’ Jeff Holmes wrote. ‘The Turks opened fire with their 12-pounders and a few shells burst right over us and it is a miracle we escaped being hit.’ The accompanying Somerset battery opened up in reply, ‘and Jacko’s guns were soon silenced’.29

A Royal Horse Artillery field gun in full recoil after firing. Godfrey Burgess collection.

Once dawn broke, Gordon Cooper was able to open fire with his machine gun, but the enemy reply soon came. ‘The Turkish guns and artillery got onto us pretty quickly, had a very lively hour or so, had to retire and were shelled all the way back,’ he wrote. ‘My horse got a pellet in the neck, very close shave.’30 ‘A battery of mountain guns—manned they say by Austrians was shrapnelling us with really admirable precision,’ Maurie Evans wrote. ‘I haven’t been so mortally frightened since Sari Bair this time last year.’31

Fred Tomlins was in the thick of it with the 1st Light Horse. ‘The Turkish machine guns made our positions rather uncomfortable at times,’ he wrote, ‘and then the Turkish artillery got the range of our led horses and played havoc with them but very few of the men leading the horses were hit.’ With considerable Turkish reinforcements moving up, the order to retire was given at 7 a.m. The machine-gun and shrapnel fire was very heavy as the men covered the kilometre back to their horses. After Lieutenant William Nelson was hit, Fred Tomlins helped to get him back. ‘We had to lay him down frequently to spell and it was very heavy in the sand,’ Tomlins wrote. ‘Shrapnel and machine gun fire were cutting the ground up all around us.’ After getting Nelson to the Field Ambulance, Tomlins grabbed a riderless horse and ‘was glad when I felt the neddy springing along under me’.32 When Maurie Evans and his mates got back to their horses, ‘we clapped our spurs in and away we went hell for leather over the ridge and into the reset little dip and after us came the sand carts rolling and ploughing up the sand like ships in a heavy sea’.33

Another 1st Light Horse trooper, Corporal Austin Edwards, had been shot, the bullet passing through his left biceps and chest and then out his back. Edwards managed to reach the waiting horses, where he was able to remount his horse, Taffy, and escape the advancing Turks. He later claimed that Taffy’s patience saved him, because not only was Edwards under fire when he remounted, but he could only manage it with his one good arm.34

‘Too much this for two thin brigades,’ Mick Bruxner wrote, ‘but still they hold and then bang, bang, bang, bang—the good old Territorial RHA are into it. Beautiful 15-pound shrapnel bursts over the Turk, taking heavy toll, but still he comes on.’ Then the light horsemen were forced to pull back. ‘A grim job this getting back under fire. Men limp on or are put in front of a mate; four boys go by carrying one in a blanket; 600 yards to go and under fire all the way . . . the line forms again.’35

Austin Edwards alongside his horse, Taffy. Austin Edwards collection. SLNSW a7206214, PXA 404/116.

Meanwhile, the 6th and 7th Light Horse, temporarily under the control of the imposing 56-year-old Boer war veteran ‘Galloping Jack’ Royston, moved out to the right flank between Mount Royston and Etmaler, where the Turkish threat was greatest. As each of his horses tired, Royston would grab another; he supposedly wore out fourteen horses that day. ‘Colonel Royston is doing some fine work, he is everywhere,’ one of his signallers observed.36 Out with the 6th Light Horse on the right flank, Major Donald Gordon Cross watched Royston approach in a cloud of dust and felt uneasy about having his horse, which was hidden behind a nearby sand hill, borrowed. ‘Forward, Cross, they are surrendering in thousands. Come on, boys, we are making history,’ Royston told him, before galloping off again.37

Colonel George Macarthur-Onslow’s 7th Light Horse took up the high ground south-east of Wellington Ridge, while the 6th Light Horse moved to the south-west of the ridge. These two regiments checked the left flank of the Turkish advance before withdrawing under heavy pressure. Corporal Carrick Paul was one of the horse holders with the 6th Light Horse. During the fighting, Paul’s squadron commander noticed Paul was holding his arm so asked him what was wrong with it. ‘Oh nothing, just a bit of a crack,’ Paul replied. He actually had had a bullet through his shoulder.38

Meldrum’s Wellington Regiment was kept in reserve after retiring behind another ridge. After the withdrawal, the Wellingtons were on the left with the 7th and then the 6th Light Horse on their right. ‘These positions were held throughout the day,’ Royston later told Chaplain William Fraser.39 One of the British generals rode up to Royston and asked, ‘Can you hold them, colonel?’ ‘If they get through that crowd,’ Royston replied, puffing on his corncob pipe and pointing to his men, ‘they can have the camp.’40 But it was a hard fight, with Royston putting every machine gun into the line and calling up two regiments of the 1st Brigade to help. Leaving their horses, the light horsemen advanced under fire some 1500 metres to their firing line. Royston ‘was a great inspiration’, Colonel Meldrum later wrote. ‘He told me I held the key of the position and had to hold on at all costs.’ Meldrum’s ‘Well-and-Trulies’ complied. ‘From dawn to dusk we were dourly defending,’ Meldrum wrote. ‘From 10 o’clock onwards it was impossible for either side to advance without heavy loss.’ Meldrum understood the key to the battle: ‘We could win by defending. The Turks had to advance or fail.’41 Four enemy aircraft appeared over Romani at 5.15 a.m. and dropped about 30 bombs, and at 6 a.m. Turkish artillery began shelling Romani station. As day broke and the heat rose, the light horsemen fought to retain Wellington Ridge.

A camel supply train at Etmaler. Walter Smyth collection. Courtesy of Robyn Thompson.

German officer Major Mühlmann was behind the centre of the Turkish attack looking down from a high dune over Romani. He watched as the light horsemen retreated before the Turkish advance only to take up new positions further back. ‘The Australian Cavalry fought in a most exemplary fashion,’ Mühlmann later wrote. ‘Many a time we cursed those active and agile horsemen in their big soft hats.’42

By 7 a.m. the desperate Turks had taken Wellington Ridge and, with the wells at Etmaler less than 1 kilometre away, the threat was immediate. When the Turks on the crest of the ridge opened fire on the camps at Etmaler, the British artillery responded and cleared the crest. Jim Greatorex wrote of how the artillery ‘made “Johnny” sit up and take notice’.43 The machine-gunners also did a job on the Turkish force. Heinrich Römer-Andreae was one of the Germans in the attack that reached the heights east of Romani at about 8 a.m. ‘Scarcely had we looked over the top of the range—when a tremendous machine gun fire was experienced by us,’ he wrote.44

By extending their left flank to get in behind Romani, the Turkish force was now vulnerable to an attack on that flank. Chaytor’s New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and Wiggin’s reformed 5th Mounted Brigade stood ready at Hill 70 for such a stroke.45 Back at Kantara, however, General Lawrence was in no position to give Chaytor the order to strike, as communications with Romani had been cut by Turkish artillery fire. Bert Billings simply noted, ‘Things serious.’ When the line to 3rd Light Horse went out at 10.45 a.m., Jeff Playfoot and Billings went out to fix it ‘and got peppered all the way, one big shrapnel bursting right over us and splattered all round, but missed’.46

A well in the sand hills near Romani. Royal New South Wales Lancers Memorial Museum collection.

Meanwhile, Turkish troops continued to advance around Chauvel’s right flank and he had to extend his line to cover the railway. He also realised that if he could get his two brigades out of the line and mount them up, he could make the attack on the Turkish left flank himself. Chauvel asked that the British reserve brigade take over his lines but once again the absence of Lawrence delayed a decision.

At the enemy headquarters, Carl Mühlmann observed that ‘as time passed Kress and his staff looked expectantly to his left wing where the decision depended’. Von Kressenstein had deployed two Turkish battalions on that flank alongside a mountain gun battery and some of his machine guns. When Mühlmann went to see the Turkish commander on the left, ‘I found him very depressed . . . troops were exhausted; heat and thirst had wrought greater havoc with them than the bullets of the enemy.’ Ominously, as Mühlmann rode off he saw mounted troops moving to envelop the Turkish left wing. Scouts also reported two other mounted brigades moving up from the south. ‘All hope of victory was abandoned,’ he later wrote.47

The grim fate of a German soldier in the Sinai desert. Walter Smyth collection.

Chaytor’s force had finally reached the battle in the afternoon, and the New Zealanders and yeomanry attacked Mount Royston. Colonel Lachlan Wilson’s 5th Light Horse, which was attached to Chaytor’s brigade, advanced around the enemy left flank and ‘this proved to be the turning point’. From 4 to 5 p.m. the Turkish forces on this flank put up the white flag.48 At 5 p.m. Bill Peterson, who was sheltering with the signal section in a palm grove, noted that ‘the Turks around our flank have “imsheed” [gone away] and are apparently in retreat’.49 By 6 p.m. the remaining defenders had surrendered. Most of the prisoners taken were desperate for water. ‘We could have caught hundreds more had our horses been fresh,’ Gordon Macrae wrote.50 ‘They retired at night a beaten mob,’ William Burchill added.51

Turkish prisoners captured at Romani on 4 and 5 August 1916. Royal New South Wales Lancers Memorial Museum collection.

The Turkish force may have retreated but it had not been beaten. That evening Heinrich Römer-Andreae kept watch for the Allied advance. ‘As the enemy was very bold I scarcely kept under cover,’ he later wrote. A young Australian lieutenant, Alan Righetti from the 2nd Light Horse, had been killed during the day and Römer-Andreae was later brought the identification disc by a Turkish soldier. In 1920 he wrote to Alan Righetti’s mother, telling her, ‘Your son fell as a hero.’52

That night, Chauvel redeployed his light horsemen. ‘In the evening all the mounted men walked round to the right flank, the infantry taking our places,’ Maurie Pearce wrote. ‘More infantry reinforcements arrived about dusk and lined the hills on the left flank of the Turks.’53 There was little sleep for the signallers. ‘I was kept going from midnight until about 7 am rejoining lines which were continually getting broken by rifle fire and shrapnel,’ Robert Farnes wrote.54 All night the field ambulances worked to get the wounded out to the railhead. Tragically, there was no rail stock allocated to transport them back to Kantara, though facilities for the wounded were no better there.

The British officer Lieutenant George Wallis had been severely wounded by artillery fire at Romani and was lying on a stretcher at Cairo railway station when a ‘kindly Australian put his wideawake hat over my face’ to shield him from the sun. When he was moved it was therefore assumed that Wallis was Australian, so he was taken to No. 3 Australian General Hospital, ‘where they just would not let me die,’ he later wrote. Dr Hugh Poate, who had honed his surgical skills in a cramped dusty dugout at Gallipoli, carried out eight operations on the head and arm of Wallis. In comparison the British Nazarea Hospital in Cairo ‘had a foul name’ and Wallis thought he ‘would have died for a cert’ there. Here he came under the care of the Australian nurse Beulah McMinn. She told Wallis how the nurses had heard him in a delirium talking of his wife Mollie and his newborn son ‘and we just couldn’t let you die’.55

Lieutenant George Wallis and the Australian nurse Beulah McMinn at No. 3 Australian General Hospital in Cairo. ‘We just couldn’t let you die,’ she later told him. Hugh Poate collection.

Back at Romani the exhausted light horsemen got what rest they could in the knowledge that they would be back in the saddle well before dawn. ‘We gave the bridle reins a twist around one foot and lay down anywhere and dropped off to sleep,’ Fred Tomlins wrote. ‘Our horses were about as tired as we were and did not disturb us.’56

A Turkish officer alongside his German counterpart. Ralph Kellett collection.