… THE TRIANGLE

Andy completed us.

—Ondine

Victor Bockris: Andy’s Factory always worked with a triangular group at the head. It comes directly from the family. He treated the boys the way his mother treated him and his two brothers. The idea is to keep each person in competition for your attention. “Who loves me most?” … “Me, me!” … “No, me!” This is exactly what happened. These people were young and easy to manipulate. They wanted the attention. When Andy gave you his attention, it was like a drug. He would shine his light on you. It made you feel like he was really only concerned about you. He’d make you feel beautiful, which wasn’t so hard because many of them were beautiful. In those early days, before the thing became so big, where I think he lost control of it, there was just a little tight group.

Billy Name: It sort of started out in that old New York Eurocentric way of an older artist keeping younger artists. The other artists had pretty boys around, but it was the tail end of that culture of that era. For instance, Andy and I would often go to Rauschenberg’s studio, and his boyfriend was a dancer in Merce Cunningham’s Dance Company. The arts culture was integrated like that. Gertrude Stein was still the queen of literature, with that whole hashish Alice B. Toklas thing, and a person having a younger lover or someone they were keeping was still going on, so that’s how I started out my relationship with Andy.

Victor Bockris: Andy relied upon Billy, and Billy was certainly reliable. He was the only one allowed to live at the Factory. He was the gatekeeper, the key man. In those early days, before the life ravaged him, he was just extraordinary. He was part of the Judson Dance Company, closely associated with those people at the Judson, with Merce Cunningham and John Cage, the avant-garde. That was a door to another world, into which Billy took Andy. He also became a great photographer. I would argue that Billy Name was one of the great photographers of the sixties, in terms of capturing the movement and the spirit of that world.

Robert Heide: I first met Billy Name, whose name was Billy Linich, at the San Remo, a bar on the corner of Bleeker and MacDougal. It was quite a mix of people, a lot of the theater crowd. It wasn’t just gay. I became quickly infatuated with him because he was so stunningly interesting and beautiful, so we wound up getting together, having an affair. Billy might put it another way, but that’s the way I saw it. He was interested in Existentialism, and we talked a lot about that, and ‘being and nothingness,’ being there.

* * *

Billy Name is still ‘there,’ and sometimes having a simple conversation can give one the feeling of falling into a rabbit hole. As a Buddhist far more evolved than I, his altruism toward his fellow beings, even when they are complete dirt bags, can be unnerving. (“Hell is other people,” to quote Sartre.) But Billy has fond memories nonetheless. Of his salad days spearheading the ‘A-heads,’ the Silver Factory’s hyperactive amphetamine rapture group, we were to discover that he had perfect recall, and unlike some others, was not prone to hyperbole.

* * *

Billy Name: Andy and I had been lovers, but when he got this new space, we became so involved with the creation of what became the Silver Factory … And because he had just started doing filmmaking, he gave me a still camera and said, “Billy, you do the photography. I’m just going to make films now.”

Victor Bockris: The way Billy became a photographer was classic of the way Warhol worked. Andy bought himself a camera in early ’63. But in those days, having a camera was cumbersome. After using the camera a couple of times, he gave it to Billy. From that moment, having never taken a picture, Billy Name made his own film, and developed the pictures, the whole bit, from beginning to end.

Andy Warhol: My idea of a good picture is one that’s in focus and of a famous person.

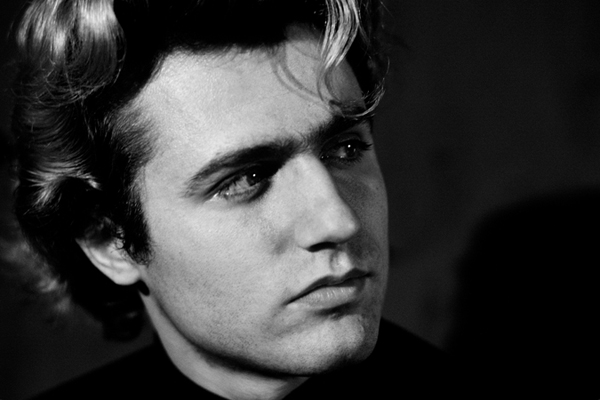

Ondine, “King’s Court Jester” (Photo: Billy Name)

Factory Manager and ‘gate-keeper’ Billy Name, in a self-portrait

Gerard Malanga, “The Prime Minister” (Photo: Nat Finkelstein)

The King of Pop Art (Photo: Billy Name)

Louis Waldon: Oh, Billy was definitely on the scene in New York. He would hang out at your place, and smoke Camel cigarettes. He would take the silver paper out of the pack and paste it on the wall, do a whole wall with silver. That was where the Factory came from … Gerard was also around. And always with girls.

Gerard Malanga: The girls? Well, I guess I had a few girlfriends during that time. But it’s not something that meant anything. It was just the way things were.

Victor Bockris: Gerard was devoted to Andy. The thing, the most important thing that Gerard walked a thin line on, was that he was actively bisexual, but primarily he was just heterosexual. He was the Factory stud; he really did have sex with all those girls who came to the Factory.

Nat Finkelstein: As far as Gerard is concerned, he was the person who gave the Factory its impetus. Gerard was the pretty guy who went out. He was never gay. He was fake gay. You can be pseudo gay but Gerard was never ever gay. He brought the girls up. And to a certain extent Gerard was the person who was the intermediary between Andy’s group of people and the Beat poets.

Billy Name: Gerard started to work as Andy’s assistant, and because of his ties in the world of poetry he started getting Andy connections into that world. He would go out with Andy to a cultural occurrence acting as if he was Andy’s boyfriend, because they all had young boyfriends, so Gerard acted like Andy was keeping him. I recall I got a bit pissed off with this, because he was pretending. You see, Gerard knew how to social climb, but it wasn’t a pretentious thing; he just knew how to manipulate things to get his position in the world. We all did that when we had the opportunity.

Gerard Malanga: I met Ondine at the Factory through Billy. Friday night we would go on this all-night binge. We would start at someone’s apartment—there was probably amphetamines going around—and end up going out in the morning looking for a luncheonette to be open. The ‘Dawn Patrol’ … I was the youngest in the group, so I never thought of myself as running the show. I always felt a part of the show—it had a life of its own. Andy was very open to ideas and activities, so we’d go to a party or a gallery opening, or a concert. Andy would just go home, if nothing was doing.

Andy Warhol: Isn’t life a series of images that change as they repeat themselves?

Gerard Malanga, Factory stud, with a comely admirer. (Photo: Billy Name)

Mary Woronov: Gerard and I were sitting down on this tacky little dirty couch and he said, “You should stay because we are doing screen tests. This will be the beginning of movies for you.” He didn’t say “you and me,” and I didn’t find out until later. He was so secretive in a way. Gerard knew that Warhol was going into movies, and he wanted to be the male lead. He realized that he needed a counterpart, a female, and I was it! … Gerard didn’t really like the other guys who hung around Warhol—Billy, Ondine. He was like, “Uh uh, no, no!” It would ruin his image … But Ondine was probably the best camp actor I knew. I once did a play with him, and he would say something, obviously being gay, but looking totally masculine. A minute afterward, I would say the same thing, obviously being feminine, but acting very masculine. It was a weird complementing thing. From that moment on, Ondine and I were totally connected.

Bibbe Hansen: You could never leave anything at the Factory. Ondine would take it and scissors and needle and thread, and staples and Lord knows what, make it into some article of clothing. So somebody was always furious. I would just think, “Why would you leave a cashmere sweater lying around here? You know that Ondine is going to make it into a turban.” He would speed madly all night. I remember one time, apparently no one had left anything that he could work with, and we came in and he was wearing an outfit made entirely out of greenish grey trash bags, which completely predicts the whole punk fashion craze by many, many years.

* * *

In the sixties, filmmaker Bruce Torbet put together a uniquely revealing collage of daily life in the Silver Factory entitled, ‘Andy Superartist.’ It was also riotously funny. We licensed copious clips, including a star appearance by Ondine, the ‘Clown Prince’ of the Factory, whose lupine grin could be frightening to newcomers, but his amazing Romanesque profile clearly belonged on an ancient coin. Here, he meticulously paints Warhol’s nails with a bottle of polish, mouthing the words ‘Polish,’ Warhol’s nationality. (Well, Ruthenia, but why quibble; it was on the border.) Meanwhile, a spry young nautically-clad Billy Name, rail thin and painfully hip, hazards a grin as he arranges a stack of Warhol’s gallon-size paint cans, which Warhol will lug about like any day laborer …

Andy Warhol: I suppose I have a really loose interpretation of ‘work,’ because I just think being alive is so much work at something you don’t always want to do. The machinery is always going, even when you sleep.

Ondine finally crashes. (Photo: Billy Name)

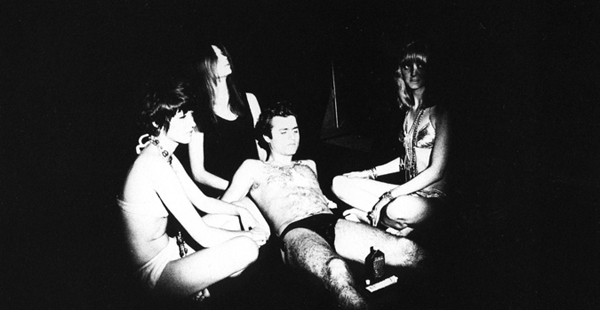

Three’s a crowd, or, as Andy would say, “a party.” Gerard and the girls get tantric at this ‘Nair’ party. They used the hair remover all over his body.

Night owls Ondine and Andy frequent Cheetah Disco. (Photos: Billy Name)

Billy Name: Andy thought Ondine was fabulous. Ondine, whose real name was Bob Olivo, was not part of the Warhol Factory as someone who worked there. He was my buddy from the amphetamine crowd. He was the grand flame, the screaming faggot who was a combination of Oscar Wilde and Laurence Olivier. So Ondine didn’t come in a worker, like Gerard, or a technical facilitator, like me. He came in as a Greenwich Village star, ready to be a star of Warhol movies.

Allen Midgette: I knew Billy Name from Italy, before he met Andy. I’m working as an actor in Spoleto, and Billy’s the lighting designer for various plays, with great success. Billy had come back to New York, into this little darkroom, and he offered me a joint. I smoked it and got … you know. At the Factory, people immediately assume that, oh, you’re an actor and you really want to be in Andy’s movie, which is absolutely not true. Billy and I had worked in Italy with Bertolucci and Passolini. I mean they did a professional job! After that experience, I could never really want to do anything but … So, who were we talking about?

* * *

Not surprisingly, we unearthed film of Billy rolling a joint, sharing his bounty with Ondine and Allen Midgette, and it’s right out of ‘Reefer Madness,’ all jittery and swooshingly hand-held by Danny Williams, Warhol’s tormented young boyfriend from ’65 to ’66, who disappeared under mysterious circumstance, an apparent suicide. His work reminds one of a Francis Bacon painting. The transgressive quality of the film may have dissipated in the smoke of time and the thankfully changing laws for medicinal marijuana, but back in the early sixties smoking pot with friends was a real bonding experience. It still is, except that now people my age really do use it for assorted ailments. This is so not fun to talk about when you are high.

* * *

Victor Bockris: Billy, Gerard, Ondine, ’63, ’64. These three guys were basically supportive of each other, on the same trip. They called Gerard the Prime Minister, and Billy was, of course, the Manager of the Factory, and Ondine was the Fool, the king’s court jester. Henry Geldzahler, assistant curator at the Metropolitan Museum, put it well when he compared Andy’s world to the court of Louis XIV, the Sun King, and for this particular period, as Ondine said, “Every moment was the right moment.” They were all there for Andy. They took it seriously—This is a cause, this is an artistic cause. And they were going through his last great painting period.

Andy Warhol: I just do art because I’m ugly and there’s nothing else for me to do.

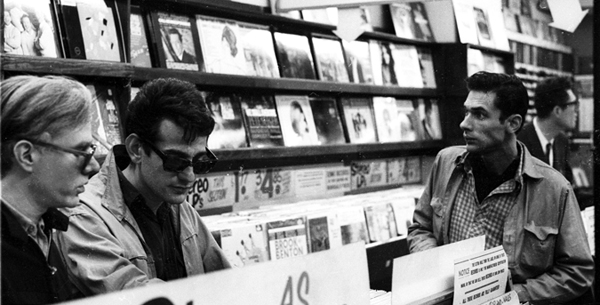

Andy, Ondine, and Billy’s boyfriend Jimmy Sullivan cruise a music store for Maria Callas LPs.

Ondine (center) and friends relax and listen to their favorite music. Note record player at left. (Photos: Billy Name)

* * *

As you may recall, Warhol had created the Flower Paintings on the advice of his friend, art curator Henry Geldzahler, who was tiring of all those Death pictures, and suggested he try something living for a change. Warhol, as ever, was open to suggestion. Geldzahler leafed through a magazine and stopped at a centerfold of flowers. Eureka! Warhol immediately began to create paintings and multiple silk-screens of Patricia Caulfield’s friendly photograph of four poppies. She sued, and Warhol was put through a long costly court case, which was eventually settled. He had to pay.

* * *

Andy Warhol: I’ve decided something. Commercial things really do stink. As soon as it becomes commercial for a mass market it really stinks.

* * *

The Flowers were exhibited in 1964 at the Leo Castelli Gallery, and sold out. Warhol claimed to like them because they “looked like cheap awning.” A few months after, the cheerful Flowers were given their Vernissage at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris to Gallic accolades. Henry Geldzahler had been right: At that propitious moment, his favored artist had been duly crowned the ‘King of Pop Art,’ and was the giddy recipient of the royal treatment from the enthralled French, who had long since decapitated most of their own. At which point, Warhol majestically declared—to the horror of his art dealers—that he was officially ‘retiring’ from painting. He would have a grand retrospective the following year of works from ’62 to ’64 (so it may indeed have been a wily move to raise those prices), but following the wild success of the Flowers, Warhol would only make art as needed, reproducing silk-screens or portraits to finance his budding film career …

Andy working in his flower bed. (Photo: Billy Name)