ANDY MAKES MOVIES … THE SILENT ERA

There is the possibility that new techniques are being explored, that other filmmakers can benefit by those techniques.

—Willard Van Dyke: Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art

We found early sixties news footage of Willard Van Dyke, who had used Warhol’s film ‘Sleep’ to make his point. He didn’t bother to mention that Warhol had been inspired to make ‘Sleep’ from the memory of shyly watching his first boyfriend sleep, while his lonely immigrant mother wandered the halls, wondering what he was up to. According to Warhol biographer Victor Bockris, he would often resort to locking Mother Julia in her bedroom, until finally relegating her to that damp basement, where she would reside, despite what Taylor Mead remembers, for the next twelve years. Disappointingly, Van Dyke didn’t go into the Gothic aspects of Warhol’s first film noir. Instead he chose to expound on the “painterly aspects of the lighting.” He also interviewed a young Jonas Mekas to talk about underground movies. Jonas told him then the same thing he told us half a century later: “Warhol was an avant-garde genius.” This is vintage Warhol, those endless silent movies of ’63 and ’64, before the ‘advent of sound,’ where the most likely accompaniment would be the audience snoring. To make time feel like it was really crawling, Warhol had insisted that these early silents be projected at 16 frames per second instead of the usual 24 (which gives an illusion of slow motion). According to Jonas Mekas, these films “celebrated existence by slowing down our perceptions.” When we screened some of them, we celebrated their existence with Moroccan hashish. You want time to stand still? Highly recommended …

* * *

Jonas Mekas: The real Warhol began with ‘Kisses’ and ‘Sleep,’ yes. That was a period when art and the time element became important, like LaMonte Young playing a single musical note for six hours. So Andy was not an amateur or naive artist; he was in touch with everything that was happening in all of the arts. Andy adopted and used and transformed, in his own way. That is why, the six-hour films. By the way, the man sleeping was the poet John Giorno, and I heard that he still had the mattress in the attic (laugh). It will be auctioned probably, at Sotheby’s.

* * *

‘Sleep’ was first screened for Jonas in artist Wynn Chamberlain’s Bowery loft, which was fitting since Warhol not only got art ideas from his friend, he’d also lifted ten rolls of 16mm film that Chamberlain had purchased to try his own hand at making an avant-garde film. One fine day, Warhol came for a visit to Chamberlain’s country house. Later that day, Chamberlain walked in on Warhol, who was merrily using up all ten rolls to shoot his boyfriend at the time, a soundly sleeping John Giorno. I watched that film without the benefit of hash, and it was almost enough to make me give up movie-making altogether (Chamberlain didn’t try again until 1969). But what do I know? What I do want to know is, how did Giorno get to keep that mattress?

* * *

Billy Name: Andy and I went to some sessions of Jack Smith filming ‘Normal Love’ on Lower East Side rooftops. For the first time Andy saw that he didn’t have to pre-conceive a film, you could just make it happen, because Jack Smith was basically conceptual; the focus of his images were his characters. Andy saw that he didn’t have to direct people, he didn’t have to have a script, he could just make a film of what was going on. But he did not find his own style of filmmaking until he said, “I am not going to do hand-held anymore. I am going to put the camera on a tripod. I am not going to move, I am just going to load the film and turn it on and off.” That became what we called the ‘Kiss’ series, the ‘Screen Test’ series, the serial art films, and they were simply these still-life portraits of a living person.

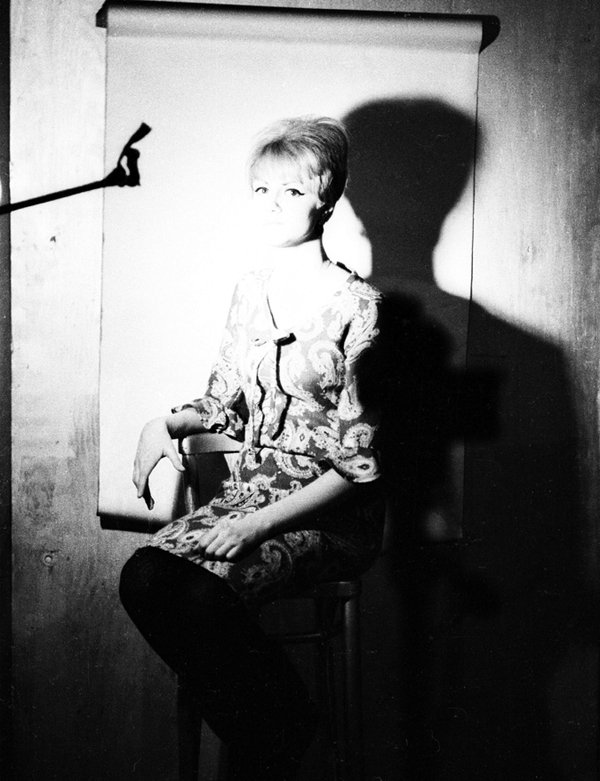

Mary Woronov: But I think for Warhol the screen test was not that. I believe that Warhol was afraid of people. For this guy who is afraid of people, to finally have this person sitting in front of him, looking at him! But it wasn’t the person; it was the film of the person, and he would become close, whereas with real people he couldn’t achieve that. So he was actually sexually fantasizing, sexually fascinated, and that is why the screen tests kept on happening. We used to watch them and we would be all bored out of our minds, and he was like, “Hummmmm, Hummmmmm.”

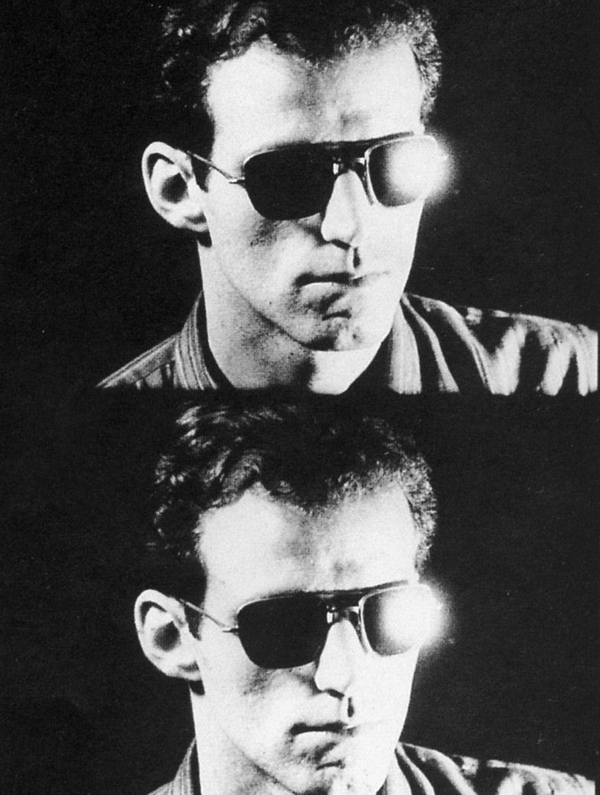

A tense Dali under pressure during his screen test. From the artist, Warhol learned the use of public visibility. At the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, FL 2014, ‘Warhol: Art, Fame, Mortality.’

Mary and Gerard try to stay awake by grading the subjects of assorted screen tests. (Photos: Nat Finkelstein)

* * *

While Warhol sat glued to the screen, mesmerized and, according to Mary, mentally masturbating, his subjects would squirm. Mary and Gerard and the others waited for the occasional on-camera breakdown, which could supply some entertainment. They also relieved the tedium by grading everyone who wound up on camera, and anybody who showed up at the Factory was fair game, even underground film luminary Jonas Mekas, who, surprisingly, twitched and grimaced throughout his own screen test …

* * *

Jonas Mekas: There used to be a chair, and a Bolex (camera), a motorized Bolex, and anybody new who came into the Factory was asked to sit there, perhaps for two minutes, forty-five seconds of film. They were called ‘Screen Tests,’ about four hundred or so of them, and, interesting what happens, when some people would sit there. You don’t know what to do. Some begin to argue and fight, or dance with the camera, or make faces. They are just by themselves, there is no cameraman, the camera is running, and there is you. What do you do, when you face the camera?

Mary Woronov: Gerard said, “Do a screen test,” and I am immediately paranoid. I think, “Well, there is no film on the camera, they’re playing a joke on me.” So, okay, should I show them, just get up and walk away? But maybe there is film there. I saw Salvador Dali’s film, when he struck this pose, but he couldn’t hold it, so he started to crack … We used to play a game with these screen tests. We would judge them, a test of whether someone has a soul. If they look at the camera and nothing comes through, they are soulless, and get a ten; otherwise they get a one or whatever.

Gerard Malanga: You can’t really have a narrative without sound I don’t think. You can in literature but it is a different idea for film. Certainly from the visual aspect, the idea of a static image taking on a moving image, it was just another appendage to what he was doing with the paintings.

* * *

Huh? Well, Gerard, I guess that discounts all the great classic silent films made before the advent of sound. In my humble capacity as a sound designer for a couple of decades, I’ve helped restore a few classic theatrical silent features for television with an ‘M&E’ track (music and effects), but the story itself, the narrative, certainly remains intact. The non-narrative style in movies would be, as film writer Bilge Ebiri of New York magazine claimed, “the cinematic equivalent of how, say, Beethoven had structured his symphonies.” Of course Ludwig was stone deaf, but still …

Nervous subject Ingrid Superstar, new to the Factory, faces the all-revealing camera. (Photo: Billy Name)

“A still-life portrait”: Billy’s own Screen Test (Billy Name Archives)

Ultra Violet: Every day we were filming at the Factory, the crowd coming in and out. One day Andy said, “You have to be there at noon.” The movie was titled ‘The Life of Juanita Castro.’ She was the sister of Fidel, and there was quite a group of people. We were just sitting, wallpaper-like, and Juanita was screaming and yelling. Marie Menken played Juanita Castro, and she was very good, very explicit. No script of course, but how she could carry on! That was the first time I was on film, which was a bit embarrassing, twitching your lips and what have you. The next day, on a sheet of fabric, we would see what we had done. I think that’s what captivates people about those Warhol movies. To be on screen is some kind of a revelation, and you can see who you are … What I love about his movies, it’s really Cinema Realité, as opposed to Godard. That would be Cinema Vérité, which is, whatever.

* * *

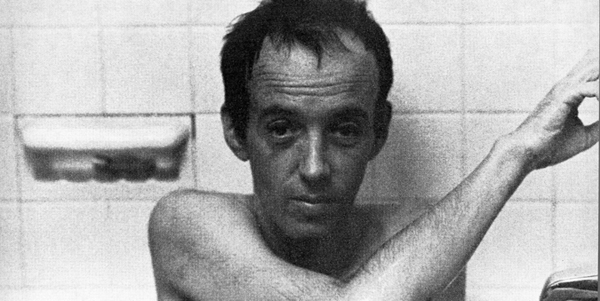

Ultra Violet, who as I mentioned was Française, actually snorted with derision when talking about Jean Luc Godard, revered ‘Father’ of the New Wave in France, famous for such films as the marvelous ‘Breathless,’ with Jean Seberg and Jean Paul Belmondo. Well, here I was, editing the ‘Factory People’ documentary in Paris, for French television with, hello, a French editor. My apoplectic editor threatened dire consequence if I left Ultra’s comments in the show. The comment stayed; the editor didn’t. C’est la vie … We also cheated a bit here (what, again?) since this ‘Juanita’ wound up a ‘talkie’ (1965) with playwright Ron Tavel taunting the throng of actors into Improv. The film is hilarious, but it’s an uncomfortable humor. In Castro’s Marxist ‘paradise,’ homosexuals were imprisoned and tortured. His wealthy siblings left, settling into NYC, and Juanita wound up working for the C.I.A. (Viva la Vida!). While ‘Juanita’ had a voluble cast, Warhol continued to focus on single characters with the screen tests. Earlier, he’d practiced his silent ‘technique’ on longtime friends like Emile de Antonio. Erudite when he wasn’t drunk, Emile’s elite inner circle included avant-garde couples John Cage and Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, where Warhol longed to belong. But when ‘De,’ as Warhol affectionately called Emile, saw the finished film (January ’65), he called his lawyer.

* * *

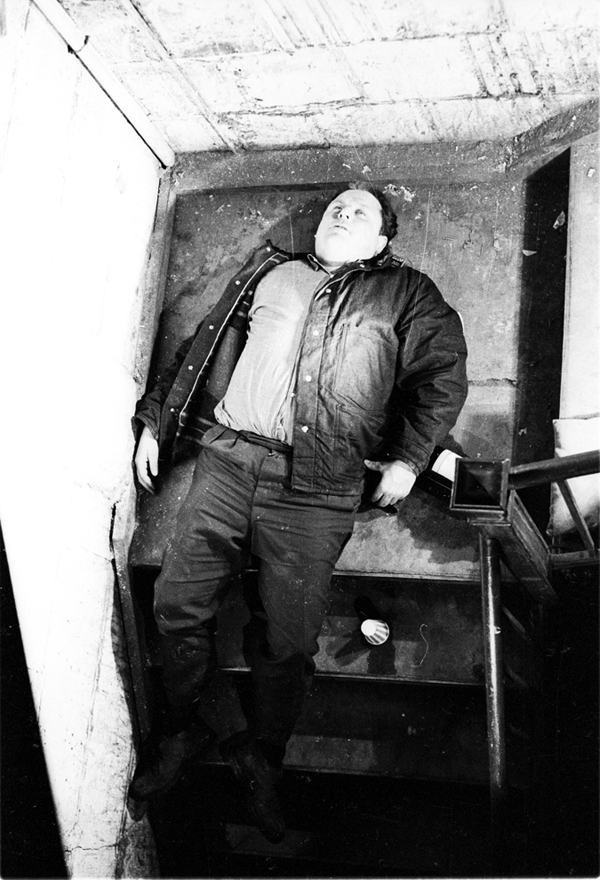

Billy Name: Emile de Antonio was a documentary filmmaker who was one of the first to tell Andy ‘how’—Andy would ask him how to make the camera work. Emile’s most famous work was the McCarthy hearings, which aired on CBS. He was a real butch heterosexual who drank whiskey all the time. So he said, “Why don’t you ever do a film of me?” And Andy said, “All right, I’ll do a film of you if you drink a bottle of whiskey on the camera.” And Emile said “OK.” Soon, he’s lying prone in the stairwell. But after he died, his estate wouldn’t allow the Warhol Enterprise to release the film.

Emile DeAntonio, in ‘Drunk,’ aka ‘Drink,’ sleeps it off in the filthy Factory stairwell (Photo: Billy Name)

Gerard Malanga: None of them were real actors, none of us studied acting. I mean, I never really considered myself an actor even though I was in some of the movies … Certainly one of the great Superstars of Andy’s movies was Marie Menken, who was a filmmaker in her own right, and there was Ondine, who was just wonderful spontaneity. Of course, one of the greats of all times, luckily still with us, was Taylor Mead. Taylor was initially more of a trained actor but totally out of the ordinary. I would put those three on the top: Marie Menken, Ondine and Taylor Mead.

Taylor Mead: There’s a town called Tarzana, outside of L.A. And I thought—I think it was my idea—that we should make a movie where I’m Tarzan. Andy loved for people to suggest something to him, spontaneously. So, we made ‘Tarzan’ and the Beverly Hills Hotel pool was my crocodile infested lagoon. Dennis Hopper was my stand-in. If I had to climb a tree to get a coconut, I’d hand Dennis money on camera and tell him to go climb the tree. And he was a young, he would climb these horrible coconut trees. It was a great deal of fun. I think I edited it and put on the music. We used every inch of film. There were no double takes. It was impossible in the sixties to do a scene twice, except for Hollywood people. We only showed it a few times, and the art critics said, “We don’t want to see any more two hour films of Taylor Mead’s ass.” My sarong kept falling down while I was climbing the trees.

* * *

We watched Taylor and Warhol’s film ‘Tarzan and Jane, Revisited … Sort Of’ in its entirety, and peed our pants. So, of course we licensed lots of the footage of Taylor and Dennis Hopper in his youthful, chest-pounding, loin-clothed glory. They shot it amid the luxurious foliage of the Beverly Hills Hotel pool, where Warhol’s favorite film goddesses had often preened. His ‘goddess’ in this film, the big-busted brunette Naomi Levine, cavorts in the sea, her enormous breasts floating like buoys. She also takes a languid bath with Taylor Mead, thus earning them the dubious credit of being the first actors to strip for a Warhol film. If you get the chance, stop by the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and ask for it, or wait for a holiday screening at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Otherwise you’ll have to settle for our film, and those few moments of fabulous … After the Tarzan film, Naomi’s neediness began to get on Warhol’s nerves. Though she stayed in the picture, Warhol soon made friends with the quintessential big-haired blonde, Baby Jane Holzer (Girl of the Year ’64). Jane reminded that she was probably the prototype for Warhol’s ‘Screen Test’ Series, when he suggested that she “Look at the camera and don’t blink your eyes.” Well, Jane, the only frames I licensed were when you blinked—otherwise it ‘sort of’ looked like a lovely photograph. At the museum rate of hundred bucks a second, nuh uh.

* * *

Warhol superstar Taylor Mead eagerly awaits his bathmate, “first underground film queen” Naomi Levine, in ‘Tarzan and Jane, Revisited … Sort Of.’

Furry-hatted Naomi Levine greets the new Warhol ‘Girl of the Year,’ fluffy-haired Baby Jane Holzer, at the ‘Flowers’ opening. (Photos: Billy Name)

Jane Holzer: Andy always let other artists do their thing. He was very generous and gave much of his time, and of himself, to other artists. He had a genius and talent, which was totally misunderstood and underestimated. You never had to go through the tense part when you were on camera with Andy, because it just happened.

* * *

For our film, we chose some outstanding Warhol Museum footage of Jane Holzer, who also starred in Warhol’s ‘Batman/Dracula.’ She’s swinging upside down in the vampire bat segment with Allen Midgette, as Robert Heide tends to her mane. Taylor Mead does pratfalls, while a saturnine Jack Smith (‘Flaming Creatures’) as Dracula stalks and sucks. I never figured out the naked guy on the table with the jumble of tubing attached to his balls, but Ivy Nicholson can usually be seen lurking nearby. When I first met Ivy in Paris, I could picture her drawing blood if I didn’t get her some red wine pronto. The word ‘diva’ translates into every language.

* * *

Victor Bockris: Baby Jane (Holzer) witnessed the Factory turning into a perpetual ‘Happening’ with some degree of alarm, though she thought some of the drugged-out performances “brilliant.” Baby Jane became Andy’s first Superstar. He escorted his beautiful young Park Avenue socialite to openings and parties, attracting more attention from the press. Andy loved the press.

Jane Holzer: Andy was just standing there in the middle of it watching the whole thing happening. I don’t think he believed at the time that it was happening, but he had some sort of genius putting it all together.

Andy Warhol: You have to be willing to get happy about nothing.

Ivy Nicholson: Andy and I met at a cocktail party in New York. I was kind of looking for work—I did something naughty in Europe, but I can’t speak about it … Jane Holzer was there, and Andy and I were looking at one another like animals, like “Wow! Who is he? Who’s she?” Andy told Jane to go over and tell me that I could be in a movie next week! Just like that! He did intrigue me from the first moment, the first taste of the movie. It was called ‘Wives of Dracula’ on the Peabody Estate, and we had the limousines taking us there of course … You can see it in that movie; I am looking at Andy and falling in love with him. That was with Jack Smith and Jane Holzer and Naomi Levine. No dialogue, no script, just running around saying anything we felt like saying. Andy did one head shot of me with blood dripping out of my mouth, and you can see that I am falling in love more and more with him.

Ivy Nicholson & Baby Jane Holzer take a break on the famous couch between takes in the filming of ‘Batman/Dracula,’ in 1964. (Photos: Billy Name)

Group Therapy. In Warhol’s ‘The Life of Juanita Castro,’ star Marie Menken sits at the center of her notorious ‘family.’ Rom Tavel, the screenwriter, is top center. Ultra Violet sits “wallpaper-like” at the far right.

* * *

It seemed that Ivy was not the only star in love with Warhol at the time. The temperamental Naomi Levine, sensing a change in the frustratingly passive Warhol, and jealous of newcomer Jane Holzer, became more demanding of his time. She began to abuse him, according to others who were there, at one point even trying to yank off his precious wig. Well, that was the straw that broke the camel-smoker’s back—Billy Name firmly slapped her and threw her out, setting up a scenario that would oft be reenacted in the Silver Factory chronicles … Allen Midgette, so good at mimicking Warhol, always tried to keep a cool head when thrown into one of the Silver Factory’s spicy film stews, to no avail. Pass the Tabasco …

* * *

Allen Midgette: Andy called me and said, “Oh, Allen, I’m here with Mary Woronov and Ivy Nicholson and Ultra Violet and we’ve got a limo and we’re going to go stay at Henry McIlhenny’s house in Rittenhouse Square and make a movie and I thought maybe you would want to go?” I thought, oh, what the hell. So we arrive there, and it is magnificent! Henry has this five-story mansion with antiques, Toulouse Lautrecs on the wall, that French sculptor (Rodin), Degas. I’d seen these things in museums! And I am thinking, “Oh my God.” I couldn’t understand why a rich person would have Andy and all these weird people come to their house. Henry McIlhenny was a big patron of the arts and the heir to … McIlhenny’s. Tabasco. Sauce.

Ivy Nicholson: We did many naughty movies, and they would let him! It would be an honor to have Andy Warhol—to say, “Oh, he shot on my grounds.” He would do pretty naughty things, but it was art. Really! It was art. He liked shocking people. That is what Salvador Dali was into, too. You can have the best art, but if no one has ever heard of you, how can they buy it? So, Andy knew about making publicity.

Allen Midgette: The next day, Andy says, “We’re going to go to this client’s penthouse, and they’re going to let us shoot there.” Well, we arrive at the hotel and Andy gets out, goes to the trunk of the car, and he has a painting that he quickly staples to a frame. I could not believe what I was looking at. So, we go up to the penthouse. They had a pool, a sauna, the whole works. Andy says, “Uh, well, why don’t we take a sauna?” And I’m thinking, “He’s not going in the sauna with that wig on, whatever, the makeup.” But I’m a child of the sixties, so to speak; I’m ready to take my clothes off. We come out of the sauna, and now Andy says, “Why don’t we shoot something by the pool?” Oh, okay. So now, we’re standing by the pool and there’s three actresses (Mary, Ivy, Ultra Violet) who are, you know, they’re not madly in love with each other, let’s face it.

Andy gets his staple gun and goes to town. (Photo: Billy Name Collection)

Ivy Nicholson: Well, there was some jealousy. We were all such drama queens … We only got a hundred dollars as salary, but no one noticed that. I mean, to suddenly become a star! You were a star!

Allen Midgette: So, there is Ivy Nicholson, standing in a very rigid position. She suddenly pulls out a photograph and says, “This is my uncle, he was an alcoholic; he died at thirty-seven.” All this stuff is coming out and I am thinking, “What is this all about?” So then, that film was over. If you can call these things film, that was the film. Hello?!

* * *

Allen had been a serious actor in Italy, working with Bertolucci and Passolini. In 1962 another future Warhol star was also in Italy, strolling through Fellini’s ‘La Dolce Vita’ at fifteen. Nico called Allen “the Italian movie star,” which rankled a bit, but Allen was mostly good-natured about the jabs he endured as the token Factory hippie. He and Ondine made an early Warhol film called ‘Jail’ on the site where Jonas Mekas’ Film Anthology Archives now stands, on Second Street. But back then, it was a prison and courthouse … Allen Midgette’s ‘Jail’ is not to be confused with the Bibbe Hansen film, ‘Prison’ (1965), another Warhol inspiration. When Warhol met Bibbe, she was a teenager living—more or less—in the downtown loft of her famous father, the ‘Happenings’ artist Al Hansen, who was not exactly a ‘hands-on’ parent …

* * *

Bibbe Hansen: Andy looked over and he said, “And what do you do?” My father beamed proudly and said, “I just sprung her from jail.” Andy’s eyes grew wide. “Really! Tell me all about it!” … I made two versions of ‘Prison.’ The first one with Edie and I alone was kind of spare, but it was like a beautiful early Godard black and white. It was a typical classic Factory thing: The picture of one, or the sound for the other didn’t come out. So they put the two together to make one.

Jonas Mekas: When they went into sound, Andy needed assistants, people who knew more about cameras and sound, and those assistants began imposing their own styles, views, and contents. I mean, much of the time Andy asked them to do this and that. With the early two films with Mario Montez, when there’s a lot of zooming-in-zooming-out, he did that himself. He was fooling around with that technology.

Rising Superstar Edie Sedgwick & pretty neophyte Bibbe Hansen co-starred in both versions of ‘Prison,’ aka ‘Girls in Prison.’

Sheepskin-clad Ondine plays a shyster lawyer trying to help Allen Midgette get out of the film ‘Jail’ and save his movie career. (Photos: Billy Name)

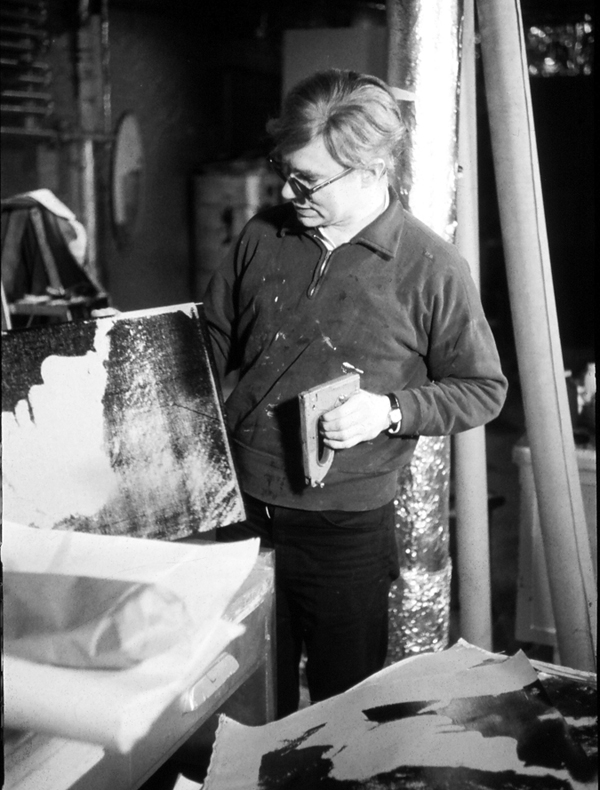

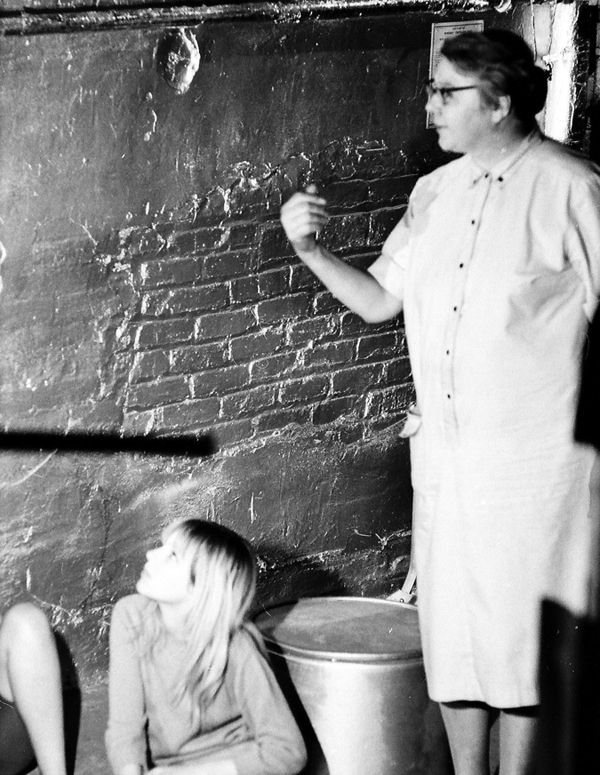

Marie Menken, the warden in ‘Prison’ shows young Bibbe Hansen the ropes. (Photo: Billy Name)

Billy Name: Great new products were now coming out for filmmakers! You could actually make movies without lights; you just did this brilliant halogen from one side and then it’s total dark on the other side so that you have that black and white harlequin face. The bodies are floating in space because the contrast is so intense. So, we were using the new tools and materials simultaneously with having the opportunity to have these crazy, brilliant characters expose themselves in our films.

* * *

Warhol’s nascent film career offered everyone within shooting range a chance to act out on camera, though the recorded results could often be brutal. Those we interviewed may have had angst aplenty amongst themselves, but virtually all of them agreed: The combustible mix of hustlers, hookers, drug addicts, displaced drunks, and lost souls often led to the very violence that Warhol feared. And these were the silent films!

* * *

Andy Warhol: The Factory was a place where you could let your problems show, and nobody would hate you for it. And if you worked your problems up into entertaining routines, people would like you even more, for being strong enough to say you were different.

* * *

Warhol’s early film Factory was not simply a company of misfits and malcontents. He also got a number of sane socialites and heiresses to do things they would never have considered had they not been viscerally connected to the arts …

* * *

Ultra Violet: Oh yeah, I had the world’s most famous tongue. I think some people have measured it from inside to out, and it was about twelve inches. But in all these years it has shrunk a bit. We did do a movie called ‘Kiss.’ Warhol had seen my tongue and he said, “You must do that film.” He must have had a million people in that film, kissing. My tongue would go in and out, and stretch out and go up and right and left, like those cows when they eat. I did some photos kissing (artist) Edward Rucha … It’s just kiss, kiss, kiss.

Mary Woronov: Yeah, yeah, the tongue. Ultra had the longest tongue in the world, and it was tilted at the end. It was amazing! And everyone was like “Stick out your tongue,” so all of a sudden this thing went out …

* * *

Ultra found us a photo of her phenomenal bovine tongue, and, yeah, no exaggeration there. So, already in our film we had Warhol cows mooing on wallpaper in the Castelli Gallery, vampire bats chittering in ‘Batman/Dracula,’ Factory cats meowing amid the silk-screened flora and fauna, and, naturally, a fruit course, tittering …

* * *

Mary Woronov: The first film I did with Warhol, they shipped in this lunatic Puerto Rican, Mario Montez. I sat around bored out of my box, and he’s tittering away. I don’t remember filming, just Mario putting on his make-up for nineteen hours. The next movie was ‘Hedy’*, the shoplifting of Hedy Lamarr. Mario is my prey, and I am lethal, being six feet tall, actually. I’m the police and ‘she’ is the kleptomaniac, and some kind of sexual thing is going on. She looks at me and I bend her fucking arm, and that’s it, right? No, Warhol looks up and goes, “Uh, there is still film in the camera.” Ronnie gets hysterical, “Arghhh, ughhh!” and flaps around like a fish and finally dies on the floor. The end. Warhol takes the film out of the camera. There is no such thing as a cut. Even I know this is wrong, but I guess that’s another way to learn that nothing is wrong.

Billy Name: Andy wanted to make stars. Probably the first was Mario Montez, who was also a Jack Smith star. Mario Montez became Andy’s first glamour icon. And what kind of film would he make with her? Well, whether it was Mario eating a banana or peeling a banana, she is just being Mario in her dazed glamour heaven, because Mario was a man, but looked like the screen star Maria Montez. It was just glamour, glamour, glamour. At this point he had to film everything! The first year was much more of an open space for those who were participating with Andy, because we were still totally into that avant-garde underground art world thing.

Ivy Nicholson, Jane Holzer, Jack Smith and Beverly Grant siphon blood in ‘Batman/Dracula.’

One of a sequential series of dazzling shots (which we animated) of the divine Mario Montez, Warhol’s first drag Superstar, wrapped in her dazed glamour heaven. (Photos: Billy Name)

Gerard Malanga: I was in ‘Harlot,’ and Mario Montez was the star. ‘She’ played a Jean Harlow character in drag. A boyfriend of Andy’s was also in the film, and a girlfriend of a film critic at Newsweek. Andy was shooting sound, but there was no sound. There were voice-overs, two poets talking about what was going on in the picture, but they were off camera, so you are looking at a voice-over movie for about seventy minutes. Towards the end of the second reel, you realize that actual sound is being recorded in the film, when Philippe throws a beer can and it lands off-camera. You hear it crash, and you suddenly realize that this is a sync-sound movie.

Robert Heide: For the films, there were always the assorted hangers-on, leftover Warholites like myself, who would show up. Nobody really knew, but Andy had a sense of himself as an actor, and he was no dumb blond—Andy was cultured. He loved to go to flea markets with me. We called ourselves ‘The Dime Store Kids.’ We both came out of the depression era, and think about it, that’s what Andy’s art was all about. That part of America was disappearing, so the hoarding instinct, with the Fiestaware, the cookie jars, that’s what the collectibles were about to us—Americana! Pop culture! Mickey Mouse! Andy always said he wanted to be like Walt Disney, who had a factory.

Jonas Mekas: Andy is there in the underground film world, same as George Maciunas, the Fluxus Movement, the Fluxus films. They all have something in common, but there were fifty different filmmakers involved. Same with Andy, before what one could call the ‘Hollywood period’ … What happens when you watch ‘Empire’? At first it’s slow, nothing. Then, after fifty minutes, you give up and admit to yourself to just be in it, and watch some dust scratches. It becomes a meditation. If you are able to go into that kind of state, and to watch this film, in which supposedly nothing happens, then suddenly, the white comes up on the building, the magic moment. If you can be in that kind of state, you won’t support war, you won’t fight, you are not a soldier, you are not going to kill. You are somewhere else. Yes, of course, one can be that relaxed and go into a kind of Zen experience.

* * *

This opinion of a Warhol film differs somewhat with that of another serious well-known underground filmmaker who did not appreciate Warhol’s ‘Zen experience.’ Gregory Markopoulos (‘Twice A Man,’ ‘Eniaios’) was outraged that the arriviste Warhol was receiving all this attention from Mekas and the press: “I don’t know what’s going on in this world. Here I spend ten years studying my craft, perfecting my craft, thinking, theorizing about movies and how they’re made, and this guy comes along who does absolutely nothing and knows absolutely nothing.”

* * *

Andy Warhol: Always leave them wanting less.

Victor Bockris: The underground film world had become very active and exciting, lots of parties and sex and drugs, where before it had been the poetry scene. By ’64, Andy was going into that world very fast. When he won the Film Culture Magazine Award from Jonas Mekas, the other more established underground filmmakers protested, but Andy didn’t seem to care …

Andy Warhol: You have to do stuff that average people don’t understand because those are the only good things.

Victor Bockris: There is a certain Zen Buddhism involved. Andy was an almost impossible man to pin down because as soon as you realized something about him, you had to realize that the opposite was also equally true. On the one hand, he wanted to run a male brothel. On the other hand, he was a kind of Zen guru.

* * *

Being a guru can attract all kind of folk, some of them genius and some of them dangerous, as would later prove to be quite true. But according to biographer Victor Bockris, “Warhol worried that he wouldn’t be able to have ideas without all the crazy people around, because he was really a conceptual artist more than anything, and much of his best work was based upon their ideas, especially for the way people should live.” One supposes this would make sense, even if they were serial killers (‘13 Most Wanted’) or movie stars like Elizabeth, Marilyn or Marlon. And Warhol’s wish to have homosexuality accepted seemed not so much to flaunt it in the face of people, but more to dismantle the nuclear family, which he saw as a purely economic construct, not of any real value to human beings. This, of course, did not prevent him from creating his own …

* ‘Hedy’ was one of Warhol’s least appreciated films. Its screenwriter Ron Tavel (1937–2009) started his creative life, like Robert Heide, as a downtown playwright. Though Gerard did not think much of Warhol’s new find, the “skinny, faggy-sounding guy” would play a major role in the Factory, his first collaboration with Warhol being 1964’s ‘Harlot,’ starring Mario Montez (born Rene Rivera) made up to look like an exaggerated Jean Harlow. It dealt not with the film star, but the Harlow cult that had sprung up in the sixties. In the film Tavel and Billy Name are heard off-camera waxing poetic on favorite classic female movie stars, while Mario eats many bananas. He died of a stroke in Key West, Florida in 2013, at the ripe old age of 78.