IN THE BEGINNING, ANDY CREATED …

Everything you do is real, is right.

—Andy Warhol

Victor Bockris: The Factory was born out of the roots of what became the Gay Liberation Movement, which was born out of the Second World War when so many returning soldiers came home with different attitudes toward gay people, because of, ah, some things that had happened in the battlefields. So there was this unusual openness and change, and the gay culture in New York was so creative in the 1950s, so dominated really by gay attitudes or intelligences, that the male groups that came out of the fifties became the trendsetters of the sixties, essentially the amphetamine faggots, the people who Andy drew closest to in the beginning, like Billy Name and Ondine. You knew those people were coming out of a reaction to the fifties … One of the least known periods of the Silver Factory is that early period. Andy is starting to make films but he’s still seen as an artist. It’s also not known that he did paint, quite a lot in the fifties. He destroyed all the paintings. But he was trying, and he did some works that signaled what was to come.

* * *

Victor Bockris wrote the first definitive biography of Warhol in 1989. The two had become close over the years, with Bockris dedicating to Warhol his meticulous study of mutual friend William Burroughs. While Warhol moaned that, “Nobody will buy a book about me,” his biographer persevered, talking to family, friends and enemies, anyone who had known his taciturn subject from the beginning. Bockris, all proper British disdain and diction, reminded one of a rather dissolute crow. At the time of our interview, he was cohabiting with his demented cat in genteel disarray, well, squalor, at the Chelsea Hotel. We tried to ignore the crimson scribblings covering the walls, as if written in blood. Perhaps he was working on a new book. Bockris had much to say about the Warhol Family, and in the end suffered the same sad fate of many of them—banishment … Gerard Malanga, who also lives with a couple of sickly cats, would likewise lose favor with Warhol. But in the beginning, he was the golden wavy-haired boy with the pouting lips, handsome as a Greek god and with a useful talent other than poetry, though neither paid well.

* * *

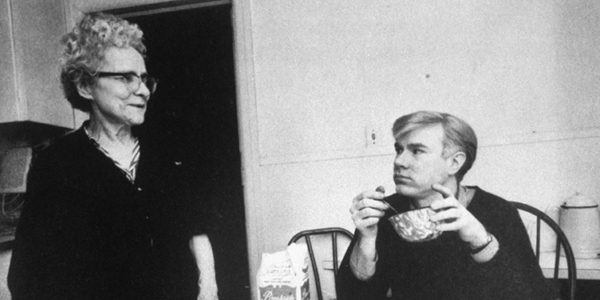

Gerard Malanga: I met Andy in 1962 at a party at the home of Marie Menken* and Willard Maas, who were husband and wife filmmakers. Andy was brought to the party by the poet Charles Henri Ford, who later recommended me to Andy because he needed someone to help him silk-screen his paintings. The Pop art movement was still on the runway waiting to take off; they were just starting out, all of them, including Andy. So I had no sense of who Andy was, except when I went back to his house the first day we worked together. Julia, his mom, made lunch for me, and I saw some of his Campbell Soup Can artworks in the living room.

Andy breakfasts with doting mom Julia. The inspiration for much of his early art came from her simple kitchen. (Photo: Ken Hayman/Woodfin Camp, Getty)

Baby Jane Holzer meets Andy and Gerard at a gallery opening. (Photo Billy Name)

… Everyone we spoke to had vivid memories of the first chance encounter with Warhol, some from waaay back, like Gerard Malanga and Billy Name and Stephen Bruce, whose famous frozen hot chocolate sundae was also unforgettable …

* * *

Billy Name: When I first met Andy I was just paying my rent by being a waiter in a posh coffee house on the Upper East Side called Serendipity. Andy knew me as one of the waiters, and Stephen Bruce, its founder and I were sort of buddies … It’s still there, and Stephen is still there. He showed some of Andy’s early work in that boutique. Andy would come in all the time; he was Stephen’s friend. Stephen would have some of his early collage books and drawings, but Andy was not famous yet.

Stephen Bruce: Andy and Serendipity became connected very early. We opened in 1954, and he discovered us within the next six months. We were in the basement; he just stumbled down with a portfolio of rejects and I was waiting for him with open arms. Andy was very generous. He did about thirty-five portraits of me and dozens of shoe things which I kept in my apartment. I had Andy Warhol work for sale at twenty-five and fifty dollars a shoe drawing. We had a lot of the Factory people working for us, like Billy Name. They were sort of moonlighting at the Factory with Andy Warhol, but they were making frozen hot chocolate and sweeping floors at Serendipity.

* * *

‘A la recherche du shoe perdu’ … According to Warhol biographer Victor Bockris, “Serendipity was one of Warhol’s first factories. He created works of art right at the table in exchange for meals.” However, it was quite obvious that selling drawings in a coffee shop, even one with the clientele that Serendipity attracted (like Jackie Kennedy and kids), was not going to get Andy accepted as an artist.

* * *

Stephen Bruce: At first, I never thought Andy changed his shirt. I said, “I see you every day in the same shirt.” He said, “Oh no, I bought a hundred of them. I wear a new one every day.”

Billy Name: “Gay” wasn’t the word then. It was mostly faggots—anybody who was successful. There is no really kind term to express the homosexual world before the gay revolution happened. But it was a sub-culture, because everyone was so terrified and paranoid all the time of losing their jobs … So the Warhol Factory was very instrumental in allowing those revolutions to happen and become known.

Gerard Malanga: I’d started working for Andy in June of ’63, in a building that used to be a firehouse on East 87th Street, two blocks from where Andy lived with his mother. Andy was renting from the city for a hundred dollars, but in October he’d received a notice saying that they were putting the building up for auction. In February, Andy signed the lease on what would become the Silver Factory. When we moved in, all business shifted to the Factory. The townhouse now became off limits to the media, or to even Andy’s friends for that matter. In hindsight, he realized that it was a good idea, to keep his situation private. Nobody ever went back up to 89th and Lexington Avenue. The only person there was Julia, his mom.

* * *

We’d heard so many stories about Warhol’s beloved mother that we put some into the series. Warhol looked so much like Julia that he could have been her clone, and she would seem to be the culmination of every hoary cliché explaining “why good boys go gay.” While Julia may have brought Warhol comfort in those early New York years, she could also be cruel to her fragile son, making him feel ugly and unloved. And her constant presence was a reminder of his poverty-stricken childhood. “Ma” kept to her immigrant Slavonic roots, making little effort to master English, and could seem quite crone-like to the uninitiated, especially when she drank. She roamed the cluttered townhouse with her yowling collection of quasi-feral cats, a scene from the pages of a grim European folk tale. By the advent of the sixties, Warhol wisely decided to banish Mom to the basement.

* * *

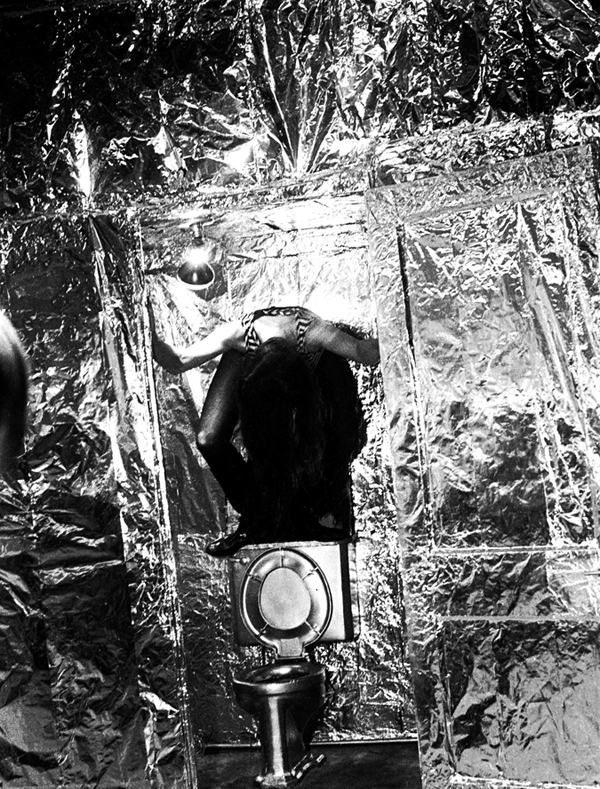

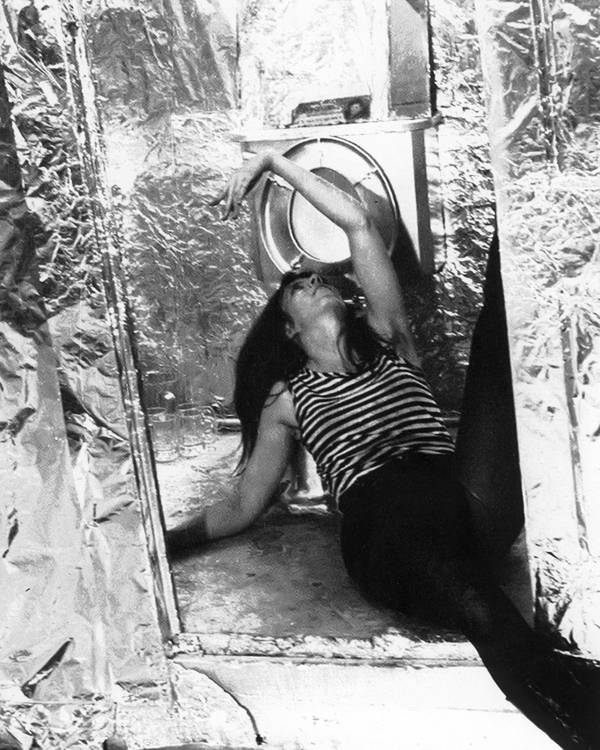

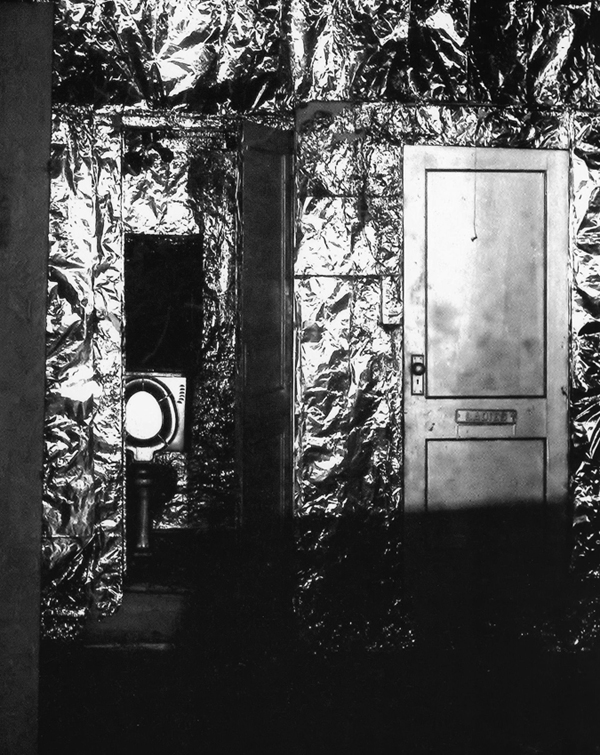

Billy Name: At the time I was a lighting designer for the Judson Dance Company. At my apartment on East 5th Street, I had covered the interior with aluminum foil, the telephone, the toilet, everything. Ray Johnson brought Andy to my silver apartment one night, and Andy said, “Billy I just got this great loft uptown and would you do to my loft what you’ve done to your apartment?” I went up to look at it, a decrepit old hat factory. The floor was concrete; the walls were crumbling concrete. Andy had set up a painting area in the front of the loft where windows were. He could only paint in the daytime because there were no electrical outlets. So he needed someone with skills for electrical installations, and I had all that from my theatrical experience. The first thing I did was to install overhead lights, spotlights, and the sound system, and make special places for Andy to work. Then I did, as an installation, an event, and a happening, the silvering of the Factory. Everything was painted silver; even the columns were wrapped in foil. The floor was silver, the walls, the furniture, the toilet, the phone (laugh). The guy would come to collect the coins and then replace the silver box with a new black one, which I would silver all over again.

Silver toilet, topped with dancer Jill Johnson. (Photo: Billy Name)

Ms. Johnson was also dance critic for The Village Voice.

Mary Woronov: The first time I came to the Factory, I was an art student, and Cornell University had this program where everybody had to go and live at an artist’s studio. Rauschenberg’s studio was all white. Then we saw Warhol’s studio, which was black and silver. I could not see any art anywhere. Then Gerard (Malanga) came out of the mist. Earlier that year, Gerard had picked me up at Cornell. He’d come up to read poetry, because he was a poet, you know. I couldn’t care less about poetry.

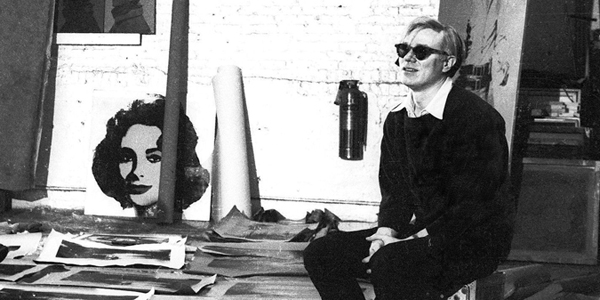

Gerard Malanga: Andy was working towards a show at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. We were silk-screening a lot of Elvis Presley paintings that were for the show, as well as Elizabeth Taylor’s portraits. We were storing them in the back of the fire house. One night, there was a huge leak in the ceiling. The next day, we discovered that all these canvases were damaged. We made a new screen and re-did that image that was slightly different, and I was instructed to shred those paintings. I did shred some of them, but I got distracted because we were doing so many different things that I neglected to finish that job.

* * *

According to Gerard, who should know, those rejected paintings that did not get shredded have been “popping out everywhere, being sold as authentic Andy Warhol.” (With all the other ‘unauthenticated’ Warhols crawling out of the woodwork these days, The Warhol Foundation for the Arts must have its hands full.) Warhol’s output from that period, roughly 1962–1964, has been the most popular, flying off the auction shelves … A celebrity death helps. Elizabeth Taylor had not been cold 24 hours before a Warhol portrait from 1963, ‘Liz#5, Early Colored Liz’ was put on the market by Phillips de Pury & Company. The buyer paid $26.9 million for one of thirteen. That same week, a bidding war broke out at Christie’s for a 1963–64 self-portrait, which showed the artist in four photo-booth poses. The winner paid $38.4 million. Also making news: Warhol’s ’66 print of surly, side-burned, leather-jacketed outlaw biker Brando in ‘The Wild One’ sold for $23.7 million, and in 2014 the ‘Four Marlons’ sold for $69.6m. In the film (made in 1953) someone asks, “What are you rebelling against?” Brando responds, “What’d ya got?” The budget was $2 million.

* * *

Andy Warhol: Making money is art.

Leo Castelli: It’s difficult to talk about Andy as a person because he’s terribly spare in his emotional manifestations. He almost created a culture, but it was based on material that was handy … He had a genius of putting all those things together, and

making a work of art of the whole climate here in New York.

“Operator, I lost my dime. Again.” Andy tries to phone home from the silver-painted pay phone.

Andy, with fellow icons Elizabeth and Elvis. Warhol had heard that in the 1957 film ‘Jailhouse Rock,’ Elvis had been inspired by Brando’s legendary rebel in ‘The Wild One.’

* * *

Considered to be at the peak of his career by 1964, Warhol defected from Elinor Ward’s gallery for the long-pined after Castelli, who, with the help of Ivan Karp and Henry Geldzahler, was taking over the art world. Billy Name—then Linich—handled the tense negotiations with the warring dealers. Castelli would soon have his own frustrations with the quixotic artist, who had his share of detractors. His messy silk-screening methods and sloppy reproductions seemed a clever mockery of mass production, a psychic slap in the face to those who still thought of him as merely a commercial illustrator, or perhaps a message about chaos and the randomness of existence. The art world eagerly awaited the answer in his next ‘statement,’ which was not exactly reassuring: “My work won’t last. I was using cheap paint.” … Warhol had more important things on his mind than dissolving paintings. He had just been to Hollywood! He and Taylor Mead had even made a movie out there! Well, sort of—the hilarious ‘Tarzan and Jane, Revisited, Sort Of’ would never be released.

* * *

Andy Warhol: Vacant, vacuous California was everything I wanted to mold my life into—plastic, white on white. I wanted Tab Hunter to play me in the story of my life.

Gerard Malanga: A friend of Andy’s, a painter named Wynn Chamberlain, took an interest in driving cross-country to Los Angeles for the Ferus Gallery show, and neither Andy nor I drive. Then Taylor Mead took an interest, so Andy invited Taylor and Wynn, and they did the driving in Wynn’s station wagon. Andy and I sat in the back seat, luxuriating across country …

* * *

One wonders about the wisdom of putting Taylor, in thrall to heroic quantities of Quaaludes, cannabis, and assorted alcoholic refreshments, in charge of a moving vehicle. Warhol, ever budget conscious, wondered about the frequent ‘pit stops’ at gas stations along the route. Were they driving a guzzler? No, they were harboring one. Taylor admitted he’d been giving blow jobs to the young station attendants.

* * *

Taylor Mead: We drove across the country, because Andy didn’t want to fly. Later he said he just wanted to see the country. So, we drove across the United States with Gerard and Wynn Chamberlain, and as we approached the West Coast, the motel signs were all … Pop art! Andy had done the Campbell Soup Cans a few months before, and it was like Pop art was meeting the great King of Pop art from the East!

Everyone is ‘On the Road’ … except photographer Billy Name.

… Pop-realist painter Wynn Chamberlain happened to be more than simply another zany traveling companion. Art curator Henry Geldzahler had told Warhol it was enough already with soup cans and coke bottles, that “Maybe everything isn’t so fabulous in America.” Chamberlain suggested to Warhol that he create a series of silk-screens depicting violence. Newspaper headlines and AP photos of suicides and car crashes would eventually litter the Factory floor. Warhol’s Death Series was divided into two parts, the first on famous deaths, the second on people no one had heard of, because he “thought it would be nice for these unknown people to be remembered.” So Warhol hadn’t invited Wynn on the road trip just because he had a handy car and a driver’s license. Why Taylor went along for the ride is quite another story …

* * *

Taylor Mead: In Kansas, I picked this sort of pseudo-modern truck stop full of truck drivers and young locals, and when we walked in it was like we were from another planet. People all came over. “Who are you? What are you doing here?” in a kind of American open way, but it was a little scary, like we were too freakish for them. So I let Andy pick the rest of the places, like this motel we were staying in … Andy said, “Oh, Taylor that bellhop really likes you, but he wanted ten bucks.” Andy had this fucking Carte Blanche account, but he wasn’t about to spend any money. The next morning Andy was like, (mimicking) “Taaaylor, the bellhop came into my room and wanted ten bucks, so I said, “The rich guy is down the hall.” I told Andy I didn’t have the ten bucks. And there’s Andy, soooo disappointed that I didn’t have a good story to tell him … Finally we got to L.A., and Brooke Hayward, Dennis Hopper’s wife at the time, called her father, Broadway producer Leland Hayward. He had a suite at the Beverly Hills Hotel, so we moved in, and Irving Blum gave us a phone number for “anything we needed.” We would have had the best hustlers in L.A., but Andy would go, “Oh Taylor, you call. My mom brought me up to never push yourself forward.”

* * *

According to biographer Victor Bockris, Warhol’s mom had probably also been responsible for her son’s reluctance to fly. Although he’d already flown around the world in the fifties with a former boyfriend, Julia harped about the death of Elizabeth Taylor’s husband Mike Todd in a small plane, instilling in Warhol from then on a lifetime fear of flying. Taylor Mead was having lunch with Julia, listening to her say, “Andy no fly. Too many big shots die in planes.” His version of the famous road trip may have been recounted to other biographers, bartenders, and anyone else who would buy him a drink, but it still had us on the floor when we shot the interview in his local “watering hole.” I mentioned that I hadn’t heard that term in a long time, and he suggested another scotch. Revived, Taylor continued. And continued …

Taylor Mead: But the trip to California was amazing! Andy was already a sensation, and we were with Marcel Duchamp. But at an opening at the Pasadena Art Museum, a cameraman from Time pushed me away to take a picture of Marcel. I said, “I’m Taylor Mead, who the hell do you think you are?” Then we made a huge party with all the wealthy of L.A. and I couldn’t get in! Marcel came out and took me to his table. Later in New York, he invited Ultra Violet and me to his house. I saw a painting on the wall, and said, “My God, that’s the most beautiful Matisse I’ve ever seen!” I did not know he was married to the daughter of Matisse.

Vincent Fremont: All artists are visual beings. They should be allowed to do anything they want in the visual realm. Andy took the heat, coming out of history and Marcel Duchamp and that era. He took it a huge step forward. The Campbell’s Soup Cans—they said, “But that’s not art!” I still see this at retrospectives. There will be two old ladies in front of the canvas clucking, “This isn’t art.” But that’s what distinguishes any artist who’s talented and has a vision. They see the world differently.

* * *

I’m sure those old ladies had their own vision of Campbell’s soup, since the company has been around forever. We found old cartoons of the cherubic soup kids slurping, a fifties commercial of a perfect housewife scanning rows of soup cans, threw in pictures of Warhol in the market filling his cart with his ‘models,’ seasoned them with a few finished paintings, added a pinch of cheerful music, and stirred it all together. Voila! Art! … Henry Geldzahler, arbiter of modern art, might have thought otherwise, but he did compare Warhol to the playful Duchamp, who had also once been fascinated with repetitive imagery.

* * *

Henry Geldzahler: The Campbell’s Soup Can was the ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ of Pop art. Here was an image that became the overnight rallying point of the sympathetic, and bane of the hostile. Warhol captured the imagination of the media and the public as had no other artist. Andy was Pop, and Pop was Andy.

Taylor Mead: As Andy used to say, timing is everything, and pop schmop. But it was the right time to turn the spotlight of commerciality back onto the corporations and say, “This Campbell Soup Can won’t cost you 25 cents, it’ll cost you 25 hundred dollars.” And people bought it! I think the rich like to be slapped in the face a little bit … But then again, anyone who bought those earlier cans is a billionaire. We semi-famous people should know better.

Andy draws a soup can. (Photo: Nat Finkelstein, ’65)

* * *

Warhol’s Soup Can series of 32 paintings had a less than stellar opening at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles—only five were sold, for $100 each. The art dealer Irving Blum bought them back to keep the set intact. (In 1996, the Soup Cans sold to the Museum of Modern Art in New York for $15 million.) That first exhibition had closed in L.A. on August 4, 1962, the same day Marilyn Monroe died. Warhol had immediately decided to paint a series of Marilyn portraits. “I wouldn’t have stopped Monroe from killing herself,” he said. “Everyone should do whatever they want to do.” Warhol did twenty-three Marilyn portraits, using a publicity photo for the 1953 film, ‘Niagara’—after which he did the Marilyn diptych, 100 repetitions of the same face, the colored paint slathered on the canvas made the screens clog, giving each Marilyn a slightly different expression … The speed and endless possibilities of duplication in the silk-screening process suited Warhol’s talent as a conceptualist. Though some considered this new art to be a direct descendant of Dada-ism, Duchamp, the pre-eminent Surrealist, did not consider Warhol’s work to be remotely connected, saying it “applied to today.”

* * *

Leo Castelli: The key figure in my gallery is somebody I never showed, and that was Marcel Duchamp. Painters who were not influenced by Duchamp don’t belong here.

Louis Waldon: I met Duchamp in a coffee house in New York. He used to show up and play ‘Go’ all the time. He was a brilliant man, very funny, nice, too. Andy was totally influenced by him. Art was dead. Anything can be art, found objects that everybody was picking up. Smashed beer cans off the street; “Hey, look at this! Put it on the wall. Oh, it’s art!” And Andy saw that everybody was feeling that way. So he started making all this art. Some of it was really bad. Andy kept them. He said, “That is art, man.” Now these things are selling for a fortune.

* * *

The familiar images of Marilyns and Elizabeths, Soup Cans and Brillo Boxes, Cows and Flowers, would make Andy Warhol the iconic artist of his time. But back in 1963, Warhol’s Soup Cans had been considered a byword for bad art. Marcel Duchamp, by then considered the “spiritual godfather of Pop Art” liked Warhol’s work: “If a man takes fifty soup cans and puts them on a canvas, it is not the retinal image that concerns us,” he said. “What concerns us is the concept that he wants to put fifty soup cans on a canvas.” Warhol’s favorite dish goes on … Campbell is releasing a special edition of its tomato soup, imbedded with the immortal phrase: “Everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes.”

Marcel Duchamp patiently poses for Andy, whose work he liked despite reservations. (Photo: Nat Finkelstein)

A familiar image. Publicity still of Natalie Wood, silk-screened and multiplied into art. (Photo: Billy Name)

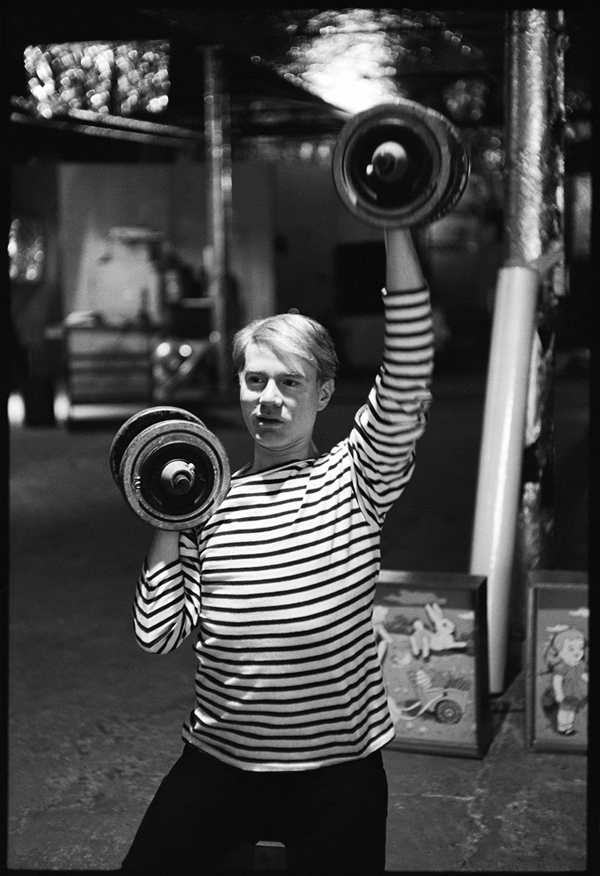

Andy works out in his favorite shirt. (Photo: Steve Schapiro)

Billy Name: Andy had won awards in New York for his commercial graphics design. He wasn’t just a fresh phenomenon, a guy from Pittsburgh who came to New York and then started doing fine art. No, he was integrated into the art community. He knew my friend Ray Johnson, this Zen master of committed collage as real life; he knew the experimental composers John Cage and La Monte Young, the underground filmmaker Jonas Mekas.

Victor Bockris: Billy Linich, who changed his name to Billy Name, was the manager of the Factory. He was somewhat the equivalent of Gerard in many ways. He was very good-looking. He had the ‘New Look.’ He loved Andy. I think they had a brief liaison dangereuse at the beginning. But it wasn’t like anyone rejected each other.

Billy Name: Andy and I had been for a time lovers, so we were intimately synchronized. We loved each other, and I’m talking in an altruistic sense. And we loved what we were doing. I had the skills that he needed to free him to make the art. Then I could make my art as the arena … That whole thing started to break down somewhat when people from the outside came in to something that had already jelled and were expecting something from it.

Nat Finkelstein: Andy needed an established photojournalist, because of that, uh, group surrounding him, people who were gay, people who were queer, people who were not going to get into a major magazine. I had that entrée. My God, by the time I went to Warhol, I had already shot two popes and a couple of presidents, so I was not awed by these people. The major photography magazine at that time was Pageant. I had essays there. I had stuff in the New York Times Sunday Magazine, and Andy saw that. I was covering the anti-war demonstrations in Washington, documenting American society, and it looked to me that Warhol and his Factory were going to be a major part of American cultural society. “This is happening! This is what is going on!” I wanted to do an essay on Andy and the Factory. Andy wanted to break out of the New York culture womb, and go nationwide, so it was kind of a marriage of convenience. Besides, I liked the girls. After a while it was a pleasure. I was the only heterosexual guy with a bunch of beautiful women.

* * *

Not quite, Nat. Photographer Steve Schapiro also covered bold faces (the Kennedys, Martin Luther King). His often-whimsical portraits of Warhol from 1963 to 1966 ensured him a place in pop cultural history. According to Steve, who I saw in Europe for Paris Photo: “Andy hid behind a posed emotionless mask which allowed him to watch everything happening around him without showing any sign of a reaction.”

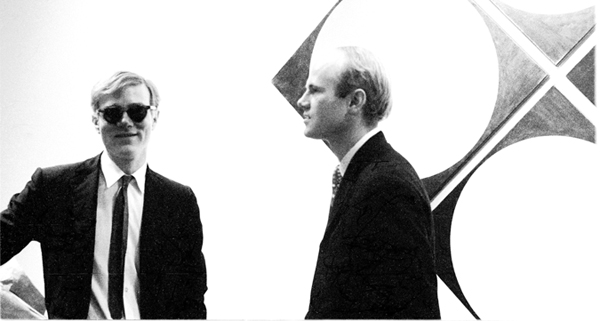

Andy and fellow artist Jim Rosenquist, also with the Leo Castelli Gallery, attend an opening for Robert Indiana, famous for his tilted ‘LOVE’ letters.

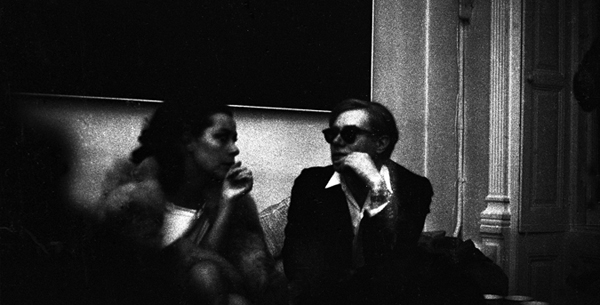

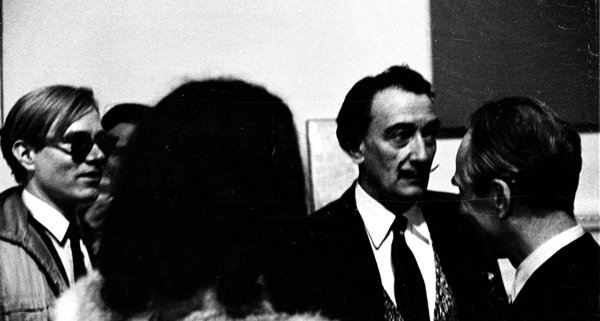

Andy attends a party for Salvador Dali at Henry Geldzahler’s chic, art-filled apartment (note small Marcel Duchamp in B.G.), with experimental avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas. (Photos: Billy Name)

… Meanwhile, Nat was so busy taking photos and other liberties that he rarely got a shot of himself. However, the few we saw of him and Edie Sedgwick, with whom he was close, confirm that he was an affable, fairly good-looking guy, and only became trollish and curmudgeonly with age. A veteran of 75 solo and group exhibitions, Nat died in 2009 at the age of 76. Interviewed in Paris where he was having a one-man show, he was refreshingly frank, if a tad pugnacious, especially after a few flutes of good French champagne, informing us that he had been “the only photographer who had the guts to give Andy orders when taking his picture.” This certainly must have endeared him to the Factory regulars. But Nat did say that he had made a good friend (not in the biblical sense) of the striking Mary Woronov, though she did not share his opinions of her pals Billy and Ondine. And she could be opinionated. Warhol was a bit cowed by Mary; she clocked in at six feet, with a mighty intimidating scowl. He wanted to call her ‘Mary Might,’ but she promptly nixed that idea …

* * *

Mary Woronov: The guys who hung around Warhol, Ondine, Billy Name—these were really, really intelligent and gay people. They were not allowed to be gay and they were terribly repressed and they ended up being screaming lunatics but really smart and really funny and I was attracted to it … Well, that and drugs.

Ultra Violet: I became Ultra Violet in 1963 when I met Andy Warhol. At the time, I was madly in love and enchanted with Salvador Dali. He used to have a phenomenal five o’clock tea, and one day in walked this personage. I thought it was a woman of a certain age. The hair was uneven, black, white, gray. Her voice was very weird. You felt you had to put a coin in her mouth for her to say something, coming from the other world. Anyway, that person said to me, “Well, you are so beautiful that we should make a movie together.” I said, “When, where, how?” He said, “Tomorrow at the Factory.” I said, “What is your name?” Andy Warhol. I had vaguely heard of him in the art world. But in ’63 that little dwafe, dwaf, dwarf* was totally unknown.

Ultra Violet meets Andy Warhol for the firs time at her lover Salvador Dali’s cocktail party.

“Leave Dali; Dali’s too old.” Ultra torn between Warhol and Dali. Art dealer Leo Castelli looks on. (Photos: Billy Name)

Jonas Mekas: In Andy’s cinema there were several stages. First, the silents. The camera gazes for a long time. ‘Sleep,’ ‘Haircut,’ ‘Mushroom,’ ‘Eat.’ Then he went into sound. I will tell you why Andy went into sound. I filmed ‘The Brig,’ for the Living Theatre, and the theater was closed by the police. We went onstage with the actors one night, to film secretly. I needed a sound camera, so I chose an Auricon, which was used by journalists and news people because they could immediately develop it. The evening after I shot ‘The Brig,’ I invited Andy and the Living Theatre people. Andy was so impressed what you can do with this camera, so easy, one person. By myself, I was a one-man team (laugh). That is when he went into this early sound period.

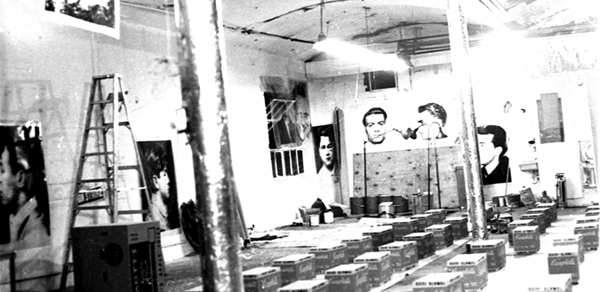

Victor Bockris: Andy had started to make films, but it wasn’t known yet. So he was still seen as an artist. Which means a more limited audience, a more limited press. So, in a sense those were quiet days. There were some beautiful photos of Andy and Gerard making the Brillo Boxes, where you see the whole room full of these old boxes, and there’s the two of them crawling around the floor doing bits and pieces.

* * *

Along with Billy’s iconic photos, we licensed clips from a film by Marie Menken, in her own unique scatter-shot style, of the boys and their boxes, scrambling around like factory workers on overtime, which I suppose one could say they actually were. When we later attached Menken’s manic filmmaking to sixties archive footage of the real thing, actual Brillo Boxes being packed and loaded on to a truck, you couldn’t tell the difference. One Warhol Brillo Box was put on auction at Christie’s in 2010. The estimate was $6-800,000. It sold for $3,050, 500.

* * *

Gerard Malanga: Andy was having a show in April at the Stable Gallery, various wooden boxes that we had to line up in an assembly line and silk-screen. That was Billy’s first photo documentation. He was actually photographing what that was all about, in the terms of the first art project of the Factory.

Billy Name: Gerard and I would paint the base coats on sheets of brown paper, to make them look like cardboard boxes, then Gerard and Andy would silk-screen the designs on the sides. The first show that Andy had at the Stable Gallery was all the Brillo Boxes and the Campbell’s boxes, and I designed the layout. At the gallery, it was the day of the show and the boxes were just being delivered. Andy had to go home and get dressed for the opening, and he said, “Billy go over and set up the show!” (laugh) So I said, “I’ll just do it like a warehouse.”

Andy, Gerard, and Billy work overtime for the Stable Gallery opening. (Photos: Billy Name)

Campbell’s Boxes in production at the Silver Factory. On the walls: mug shots from ‘13 Most Wanted Men.’

“Like a warehouse.” Billy gets creative with boxes just before the big show.

Brillo Boxes on proud display by artist Andy. (Photos by artist Billy Name).

* Marie Menken, (1909–1970) the gifted filmmaker often called ‘the mother of the avant-garde,’ took many artists under her ample wing, among them Jonas Mekas and Andy Warhol, whom she would later follow with her camera around the Factory. According to Gerard, when he arrived at the Menken-Maas home on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights, “Marie was chasing Andy around the kitchen table trying to kiss him.” The six-foot-two Menken was hardly a beauty like Ultra Violet or Baby Jane Holzer, but she was a Warhol Superstar, making a memorable appearance in one film as a quite effective bull dyke prison guard. Gerard recalled her role in Warhol’s ‘Blow Job,’ as the below-camera presence performing fellatio on DeVeren Bookwalter (though some say the chore was done by husband Willard, which would make more sense, since the couple were both considered gay). Gerard also kept for picture posterity the firsts shots of Warhol and him taken together (in a photo booth) which he created as a Christmas card. Written on it, in Gerard’s handwriting: ‘With love from Andy-Pie and Gerry-Pie.’ It was part of his pretending they were a couple.

* My late lamented friend Ultra Violet, being French, had an interesting take on the English language, even after being here lo these many eons, which charmed the pants (almost) off our French cameraman. He was old enough to remember her smoldering Hedy Lamarrish beauty, and I could tell he was flirting and going into producer mode to show off. (He’s made about 400 documentaries.) So after a couple of hours I let him finish the interview, what the hell. Women open up to handsome producers easier than neurotic filmmakers. I had better luck with Jonas, who has an eye for the ladies, even in his eighties …