Ritual and Myth

Traditionally, the term ‘myth’ refers to a society’s shared stories, usually involving gods and mythic heroes, that explain the nature of the universe and the relation of the individual to it. Such mythic narratives embody and express a society’s rituals, institutions and values. In Western culture, myths, initially transmitted orally and then in print, have been disseminated by mass culture since the late nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, genre films, with their repetitions and variations of a few basic plots, are prime instances of mass-mediated contemporary myth. As Thomas Sobchack writes,

The Greeks knew the stories of the gods and the Trojan War in the same way we know about hoodlums and gangsters and G-men and the taming of the frontier and the never-ceasing struggle of the light of reason and the cross with the powers of darkness, not through first-hand experience but through the media. (2003: 103)

In mass-mediated society, we huddle around movie screens instead of campfires for our mythic tales. Comparable to myths, genre movies may be understood as secular stories that seek to address and sometimes seemingly resolve our problems and dilemmas, some specifically historical and others more deeply rooted in our collective psyches. The ritualistic aspects of movie-going are perhaps most apparent in the phenomenon of group spectator interaction with cult movies, as in the case of the Waverly Cinema screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) where audiences responded to certain lines of dialogue with predetermined comments and actions. But this phenomenon operates in a less dramatic fashion with all genre movies, since they trigger viewers’ expectations and engage reading strategies that are dependent on the framework of genre. This is true in the experience of any genre film, whether it fulfils, violates or subverts generic convention. In their mythic capacity, genre films provide a means for cultural dialogue, engaging their audiences in a shared discourse that reaffirms, challenges and tests cultural values and identity.

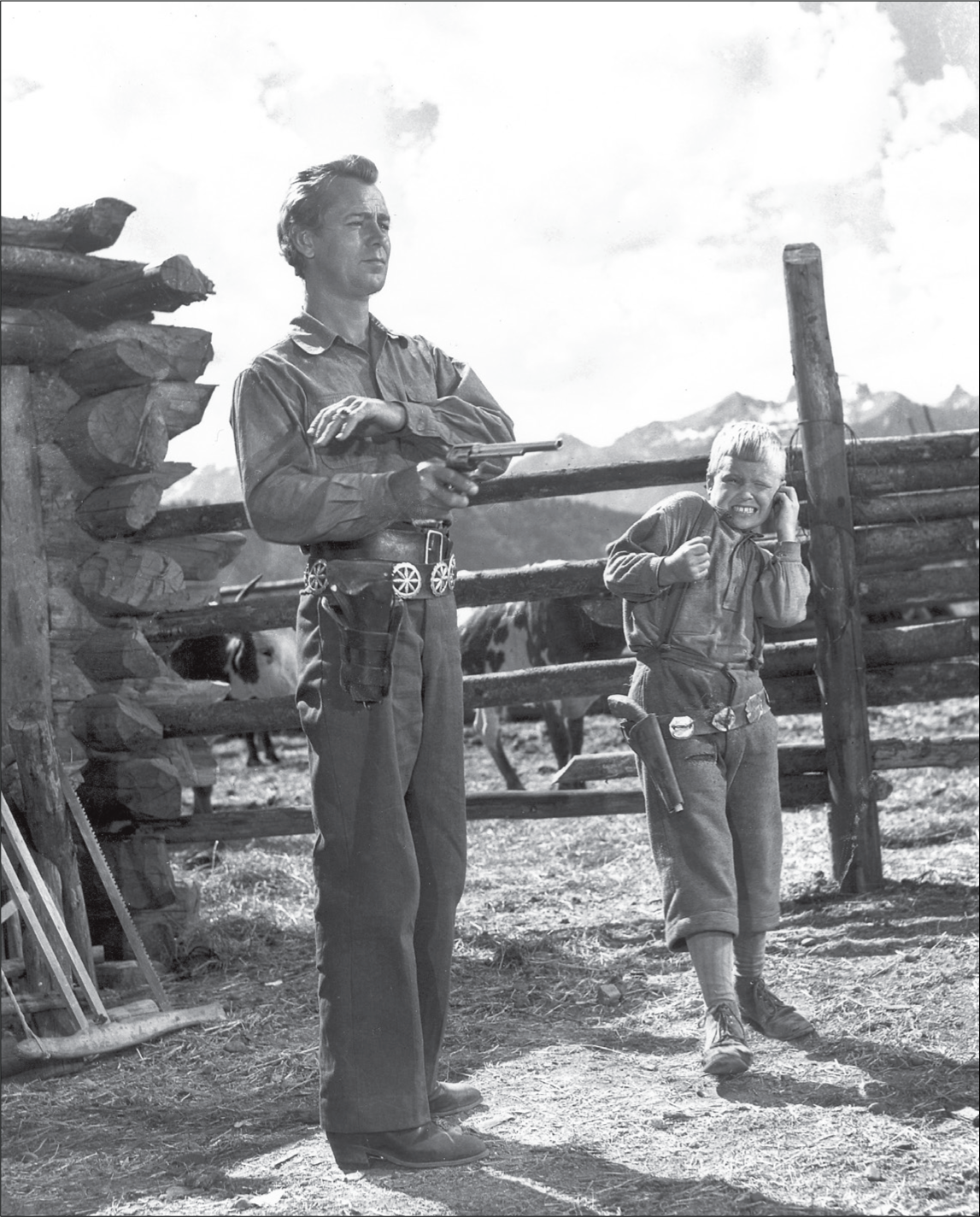

Shane (1953) is often cited as a deliberately mythic representation of the western hero. As the film opens, Shane (Alan Ladd) rides into town from the mountain wilderness, descending into the realm of mortals like a buckskinned, luminous god. Shane has greater speed with a gun than anyone else – ‘superior in kind’ to other men, as Frye puts it (1970: 33). To emphasise Shane’s mythic proportion, the story is told from the perspective of young Joey (Brandon de Wilde); along with him we look up to Shane from a low angle (which also serves the practical function of masking Ladd’s short stature), monumentalising him. When Shane rides off at the end, heading once again into the wilderness like so many western heroes before him, he ascends into the mountains as if into heaven, ultimately riding out of the frame as if to some unearthly realm beyond the world of mortals. In the post-war era of escalating Cold War tensions and the rise of the military-industrial complex, Shane offered a reassuring myth of a western (American) hero who will mete swift justice on behalf of the small farmer and average citizen. As if a god apart from mortal affairs, Shane has temporarily joined the human world in order to restore equilibrium to the social order, a clear instance of the mythic dimension of genre films.

As Shane shows, while genre films function as ritual and myth, they are also inevitably about the time they are made, not when they are set. Science fiction works by extrapolating aspects of contemporary society into a hypothetical future, parallel or alien society; thus the genre always imposes today on tomorrow, the here onto there. Yet even such genres as the western and gangster film, although ostensibly focused on particular periods of American history, do the same. The heroes of genre stories embody values a culture holds virtuous; villains embody evil in specific ways. As discussed in separate case studies later on, Stagecoach is as much about late 1930s and New Deal America as Little Big Man (1970) is steeped in the Vietnam era.

Figure 3 Shane: the camera and Joey look up to Shane

Structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1977) claimed that all cultural myths are structured according to binary pairs of opposite terms. This approach is inviting for the analysis of genre films, which tend to work by reducing complex conflicts to the equivalent of black hats versus white hats. In his influential study of the western, Jim Kitses (1970) first maps out a series of clear binary oppositions that are all variations of the conflict between wilderness and civilisation, then proceeds to analyse the work of several directors associated with the genre. Kitses’ work has influenced virtually all subsequent studies of the western, yet critics have not mapped out in any comparable detail the binary structures of other genres with the possible exception of the horror film.

History and Ideology

Entertainment inevitably contains, reflects and promulgates ideology. It is in this sense of entertainment as ideology that Roland Barthes uses the term myth. Showing how mythic connotations are conveyed in a wide variety of cultural artefacts and events from mundane consumer products to sporting events like wrestling, Barthes argues that ‘the very principle of myth [is that] it transforms history into nature’ (1972: 129) – that is, cultural myths endorse the dominant values of the society that produces them as right and natural, while marginalising and delegitimising alternatives and others. With the rise of semiology in the 1970s and into the 1980s, critical interest shifted from the signified of films to the practices of signification – that is, from what a film ‘means’ to how it produces meaning. Barthes’ attempt to deconstruct the mythic codes of cultural texts appealed both to scholars wishing to demonstrate that genres were little more than bourgeois illusionism, conservative propaganda for passive spectators, and those who saw the codes of genre as providing the possibility for ideological contestation and empowerment. Melodrama and horror proved to be particularly fruitful genres for such analyses, while more recent theoretical work on representation has opened up space for the analysis of genre and sexuality, race, class and national identity.

Although Barthes addressed cinema hardly at all, his ideas about cultural myth have influenced much subsequent work on film. His description of cultural myth applies perfectly to genre movies: ‘Myth does not deny things, on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a clarity which is not that of an explanation but that of a statement of fact’ (1972: 143). The elements of cultural myth that Barthes identifies can all be found in genre films: the stripping of history from the narrative, the tendency toward proverbs and the inability to imagine the Other. Classic narrative cinema, like myth, makes culture into nature: the movies are told in ways that eliminate the markers of their narration, as if they were a window onto the world and its truths rather than a constructed frame that is a representation. Genre movies also speak in proverbs through conventions: the romantic couple come together to marry and live happily ever after, crime does not pay, there are things in the universe that man was not meant to know. In genre movies, as Barthes says of cultural myth generally, the Other becomes monstrous, as in horror films, or exoticised, as in adventure films. In westerns, Indians are either demonised as savage heathens or romanticised as noble savages, but rarely treated as rounded characters with their own culture.

From this perspective, genre movies tend to be read as ritualised endorsements of dominant ideology. So the western is not really about a specific period in American history, but mantra of Manifest Destiny and the ‘winning’ of the west. The genre thus offers a series of mythic endorsements of American individualism, colonialism and racism. The civilisation that is advancing into the ‘wilderness’ (itself a mythic term suggesting that no culture existed there until Anglo-American society) is always bourgeois white American society. Similarly, the monstrous Other in horror films tends to be anything that threatens the status quo, while the musical and romantic comedy celebrate heteronormative values through their valorisation of the romantic couple.

The complex relation of genre movies to ideology is a matter of debate. On the one hand, genre films are mass-produced fantasies of a culture industry that manipulate us into a false consciousness. From this perspective, their reliance on convention and simplistic plots distract us from awareness of the actual social problems in the real world (see Judith Hess Wright 2003). Yet it is also true that the existence of highly conventional forms allows for the subtle play of irony, parody and appropriation. As Jean-Loup Bourget puts it, the genre film’s ‘conventionality is the very paradoxical reason for its creativity’ (2003: 51).

Popular culture does tend to adhere to dominant ideology, although this is not always the case. Many horror films, melodramas and film noirs, among others, have been shown to question if not subvert accepted values. In a celebrated analysis in the French film journal Cahiers du cinéma, published after the tumultuous political events in France in May 1968, Jean Comolli and Jean Narboni proposed seven possible relations between individual films and their ‘textual politics’. Barbara Klinger applies Comolli and Narboni’s categories to genre films, focusing on category ‘a’ films that ‘act only as conduits for and perpetuators of existing ideological norms’ both in form and content, and category ‘e’ films, which reveal a tension between style and content, hence problematise their ideological message and thus ‘partially dismantle the system from within’ (2003: 78). Pam Cook (1976) takes a similar view of B movies and exploitation films, arguing that their production values, less sophisticated than mainstream Hollywood movies, are more readily perceived by viewers as representations, hence allowing for a more critical viewing position.

Often genre movies are conflicted in their ideological view, their more critical aspirations in tension with the constraints of generic convention. John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) is a good example. A science fiction film about aliens infiltrating Earth, disguised as humans and living among us, They Live ultimately becomes the very kind of popular entertainment that the film begins by critiquing. The aliens, wanting to exploit Earth’s resources while keeping humanity pacified, have infiltrated human society and control the media, literally creating what Frankfurt School critics would call a state of false consciousness encoded in a television signal that encourages ‘an artificially induced state of consciousness that resembles sleep’. People must wear special sunglasses to become aware of the subtextual messages of the media that exhort us to be happy, to reproduce and to consume – that is, they must see through the surface of cultural texts to decode their ideological messages. Yet the film abandons this view halfway through to become instead an improbable action movie, with its hero, Nada (Roddy Piper), single-handedly destroying the aliens’ apparently sole broadcasting station and thus saving the world. Initially attacking the mass media for its distracting fantasies, They Live turns into the kind of basic super-hero adventure that drives so much of popular culture. Like The Running Man (1987), They Live ends up fulfilling the requirements of escapist action even as it condemns the media for providing it.

Dynamics of Genre

Genres are neither static nor fixed. Apart from problems of definition and boundaries, genres are processes that are ongoing. They undergo change over time, each new film and cycle adding to the tradition and modifying it. Some critics describe these changes as evolution, others as development, but both terms carry evaluative connotations. Rick Altman theorises that generic change can be traced by the linguistic pattern wherein the adjectival descriptors of generic names evolve away from their anchoring terms and become stand-alone nouns. His examples include epic poetry, out of which the epic genre emerged, and the musical, which developed from musical comedy (1999: 50–3).

One of the first critics to propose the ‘life’ of art forms was Henri Focillon, who proposed a trajectory of ‘the experimental age, the classic age, the age of refinement, the baroque age’ (1942: 10). Some genre critics accept a general pattern of change that moves from an early formative stage through a classical period of archetypal expression to a more intellectual phase in which conventions are examined and questioned rather than merely presented, and finally to an ironic, self-conscious mode typically expressed by parody. Thomas Schatz, for example, argues that genres evolve from ‘straightforward storytelling to self-conscious formalism’ (1981: 38).

Parody requires viewers literate in generic protocol, for only when audiences are widely familiar with the conventions of particular works or a genre can they be parodied effectively. In Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein (1974), a parody of the 1930s cycle of Universal horror films, the monster (Peter Boyle) comes across a little girl playing by a lake and tosses flowers into the water with her; when there are no more, she innocently asks what they should throw in now. There is a cut to a close-up of the creature looking knowingly at the camera. The connecting gaze between the actor in the story and the film viewer is based on the shared knowledge that in the most well-known version of Frankenstein (1931) the monster accidentally drowns the girl by throwing her in the water, naively expecting her to float as well, and triggering the wrath of the villagers. In Young Frankenstein the joke is based on the disparity between the innocence of the girl’s question in relation to the generic knowledge of both the viewer and (improbably) the character.

However, generic phases do not fall into convenient chronological and progressive periods, but often overlap significantly. For some, the western evolved from the supposed classicism of Stagecoach to the end of the intellectual trail with The Wild Bunch (1969) just thirty years later, and then Brooks’ Blazing Saddles marking the end of the classic western and the beginning of the parody or baroque phase. But the western was already parodied even before this intellectual period in such films as Buster Keaton’s Go West (1925), Destry Rides Again (1932, 1939) and the Marx Brothers’ Go West (1940). Looking closely at silent-era westerns and at the implicit assumptions of several important genre critics, Tag Gallagher concludes that, contrary to their shared view, there is no evidence that film genres evolve towards greater embellishment and elaboration. He cites, for example, the scene in Rio Bravo where a wounded villain’s hiding place on the upper floor of the saloon is revealed by blood dripping down, but points out that the same device was used by John Ford in The Scarlet Drop (1918) decades earlier, and even then dismissed by critics as ‘old hat’ (2003: 266). Gallagher insists instead that even ‘a superficial glance at film history suggests cyclicism rather than evolution’ (2003: 268).

Genre history, at least, does seem to be shaped to a significant degree by cycles, relatively brief but intense periods of production of a similar group of genre movies. For example, during the 1950s surge in science fiction film production, after the success of The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), there was, in short order, The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) and Attack of the Puppet People (1958) – all movies that used special effects to exploit the disparities of scale.

The detective film in the 1930s was dominated by a cycle of Oriental detective films and series, spurred by the popularity of the Charlie Chan series that began with Charlie Chan Carries On in 1931. A number of actors (none of whom were Chinese) played Chan in over two dozen films produced first by Fox and then by Monogram studios until the series finally ended in 1947. Twentieth Century Fox sought to cash in on the success of the Chan films with its Mr. Moto series, starring Peter Lorre as the eponymous Japanese detective, and Monogram also responded with its Mr. Wong films featuring Boris Karloff. Combining stereotypes of Oriental characters with the detective or mystery format, the cycle was brought largely to a halt by the outbreak of World War Two and the retooling of Asian stereotypes as enemies in war films. Altman (1999) suggests that cycles are distinguishable from subgenres in that while a subgenre can be shared among different studios, cycles tend to be ‘proprietary’, dominated by a particular studio, as in the case of the Warner Bros. biopics in the 1930s that began with Disraeli (1929). However, this claim is questionable, particularly after the decline of the studio system. More recently, the big box office success of the action movie Speed (1994, Twentieth Century Fox), with a kinetic plot involving a bomb on a bus that cannot stop or it will explode, was followed by Money Train (1995, Columbia) and Broken Arrow (1996, Twentieth Century Fox) with runaway trains, and Swordfish (2001, Warner Bros.) with its airborne bus hauled by a helicopter. Rumble in the Bronx (Hong Faan Kui, 1996, Golden Harvest/New Line Cinema), with a runaway hovercraft, was made in and produced with funding from Canada and Hong Kong, showing the ability of cycles to work not only among studios but also across nations.

John Cawelti has argued that there were particularly profound changes in American genre movies in the 1970s across all genres. Aware of themselves as myth, genre movies of the period responded in four ways: humorous burlesque, nostalgia, demythologisation and reaffirmation (2003: 243). This development was the result in part of the demise of the Hays Office in 1967 and the continuing break-up of the traditional studio system, allowing directors greater freedom in a more disillusioned and cynical era. Also, the popularisation of the auteur theory (discussed in the next chapter) permitted the generation of ‘movie brats’ – younger directors such as Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian de Palma and John Carpenter – to make genre films by choice rather than assignment. Films like Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) and Apocalypse Now (1979), Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) and New York, New York (1977), Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye and Nashville (1975), and de Palma’s Sisters (1973), Phantom of the Paradise (1975) and Obsession (1976) are genre movies by directors who had grown up watching genre movies on television and studying them in academic film programmes. With a more contemporary sensibility, these filmmakers inevitably made genre films that were at once burdened and liberated by an awareness of generic myth.

For Cawelti, the changes in the period’s genre films were so profound that he wondered whether the traditional film genres had exhausted themselves and hypothesised that ‘the cultural myths they once embodied are no longer fully adequate to the imaginative needs of our time’ (2003: 260). Certainly at different historical moments, different genres are received differently and have different degrees of popularity. As Leo Braudy explains:

Genre films essentially ask the audience, ‘Do you still want to believe this?’ Popularity is the audience answering, ‘Yes.’ Change in genres occurs when the audience says, ‘That’s too infantile a form of what we believe. Show us something more complicated.’ (1977: 179)

The shifting fortune of the western is perhaps the most dramatic example of changing audience acceptance. Once the mainstay of Hollywood studio production, the genre declined precipitously after the revisionist and parody westerns of the 1970s. In the post-Vietnam era westerns no longer seemed able to offer the kind of appeal they once did. For example, given the compromised wars and botched operations that have characterised the American military since Korea, viewers have doubted the efficacy of their armed forces, and so found it difficult to accept without irony conventions such as the cavalry coming decisively to the rescue – as in Stagecoach, when the platoon appears in the nick of time to save the day.

While George Bush was able to invoke the rhetoric of the western to bolster domestic support for his war on terrorism, contemporary viewers tend to snigger at the convenient appearance of the cavalry in Stagecoach. However, essentially the same convention enthrals spectators watching Han Solo (Harrison Ford) come back for the final showdown with the Death Star in Star Wars (1977). George Lucas’ adaptation of genre conventions for his blockbuster space adventure marked the beginning of science fiction’s usurpation of the western in the popular imagination. Indeed, many science fiction movies are like westerns, with space becoming, in the famous words of Star Trek’s opening voice-over, the ‘final frontier’. In the lawless expanse of space, heroes and villains wield laser guns instead of sixguns, space cowboys jockey customised rockets instead of riding horses, and aliens – as a movie like Alien Nation (1988) makes explicit – serve as the swarthy Other in the place of Indians. In Star Wars, Lucas designed the scene where Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) finds his aunt and uncle killed and their homestead destroyed by storm troopers as an homage to the scene in The Searchers (1956) when Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) discovers the charred and defiled bodies of his brother’s family after an Indian attack. Subsequently, there appeared a cycle of science fiction adaptations of famous westerns, including Enemy Mine (1985), a remake of Broken Arrow (1950); Outland (1981), a version of High Noon (1952) set on a space mining station instead of a frontier town; and Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), a remake of The Magnificent Seven (1960), itself a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai (1954).

The western myth survives within a different genre, one with a technological iconography rather than a pastoral one, perhaps because it is more related to our daily experience. Originally westerns appealed to audiences at a time when modernity was eliminating the frontier; now, because we are more likely to be familiar with computers than horses, and more likely to visit the new frontier of cyberspace than what remains of the wilderness, the classic western has been largely replaced by the science fiction film. Altman suggests that genres are composed of both semantic and syntactic elements – roughly distinguishing iconography and conventions from themes and narrative structures, or outer and inner form – and cites the western as one of the genres that has proven most ‘durable’ because it has ‘established the most coherent syntax’ (1999: 225). The successful transformation of the western into the imagery of science fiction would seem to be a case in point.

Case Study: The Musical – 42nd Street and Pennies from Heaven

The musical genre developed quickly after the arrival of sound in 1927. Warner Bros. particularly took the early lead with its Vitaphone system for producing synchronised sound, and released the first all-talking feature, The Jazz Singer, in 1927. By the early 1930s the studio had produced a remarkable cycle of musicals, many featuring the choreography of Busby Berkeley, including Golddiggers of 1933, Footlight Parade and 42nd Street (all 1933). With their upbeat messages of group effort and success, as well as their visual lavishness offering a stark contrast to the realities of economic impoverishment, these musicals were very popular with Depression-era audiences.

While films of every genre employ a romantic subplot, an overwhelming number of musicals are constructed around romance. On one level, the connection between music and romance is hardly surprising, given Western culture’s valorisation of music as the medium that speaks to the soul or heart, and consequently pop music’s emphasis on love as its dominant subject. Often, the romantic plot involves a developing attraction and comic misunderstanding between the protagonists that is eventually resolved with the couple getting together in marriage or its promise. This is the essential plot of numerous musicals, from the RKO cycle with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in the 1930s, to West Side Story and Moulin Rouge! (2001). In On the Town three sailors manage to find their true loves while on a one-day pass in New York City, and the narrative resolution of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954) is evident from its title.

The idealised representation of sexual desire as heterosexual romance and union is one of the mythic and ideological functions of much popular culture, including the musical. Dance, in which the partners move in harmonious physical rhythms, has served as a ready sexual metaphor at least since hot dance jazz of the 1920s. As Ginger sings to Fred in ‘The Continental’ number in The Gay Divorcee (1934), ‘You tell of your love while you dance’. In the Astaire/Rogers films, their union in the narrative is invariably signalled by a final dance in celebration of their reconciliation. In The Pirate (1948), Gene Kelly, known as a more ‘virile’ dancer than Astaire, sings the song ‘Niña’, a proclamation of his sexual prowess and indiscriminate love for all women, while dancing with bold, athletic gestures as he climbs up balconies and around various balustrades and poles, the mise-en-scène a riot of phallic imagery – even ending with a smoking cigarette popping out of his mouth – in a scene that makes particularly explicit the sexual subtext of song and dance. Musical performance provides a conventionalised way of addressing issues of sexuality indirectly, in a manner suitable to both audiences and the Hays Office. From the show’s cast in The Band Wagon to the New York street gangs of West Side Story to the female prison inmates in Chicago (2002), groups in musicals that sing and dance together express communal solidarity. The transformation of desire into romance tames any potential threat to the larger social community.

The first production number in 42nd Street, ‘Shuffle Off to Buffalo’, acknowledges the obligatory romantic union between Peggy (Ruby Keeler) and juvenile Billy Lawler (Dick Powell), but the union in 42nd Street is not only that of the romantic couple, but the larger union of the nation itself. The film’s main plot concerns the attempt of legendary Broadway director Julian Marsh (Warner Baxter) to mount a new musical show, ‘Pretty Lady’, despite the economic difficulties of the Depression and internecine and personal problems among the cast and crew. Marsh himself has lost everything in the stock market crash and tells his producers that he has agreed to direct the show ‘for only one reason – money. It’s got to support me for a long time’. Petty politics and personal interest motivate many of the characters involved in the production, but when several crises develop as opening night approaches, the characters all sacrifice their personal concerns in order for the show to go on.

Figure 4 42nd Street: everyone works to put on the show

In 42nd Street, as in Golddiggers of 1933 and Footlight Parade, the story concludes that everyone has to pull together to mount the show. The opening number of Golddiggers of 1933, ‘We’re in the Money’, makes clear the metaphoric connection between theatrical show and the economy, as the chorines, dressed in costumes representing coins and singing about being financially flush, are interrupted by men from the sheriff’s office repossessing the costumes, sets and equipment because the producer has not paid his bills. In 42nd Street, similarly, the show that must be put on is both a musical and a business enterprise. Everyone talks about the fact that the show represents an investment by entrepreneur Abner Dillon (Guy Kibee), who is hoping to date a chorus girl as his return. The beginning of rehearsals is a clash of egos and personal concerns, and the aspiring chorus girls push each other, jockeying for position on the audition line. But when temperamental star Dorothy Brock (Bebe Daniels) dumps Abner after rehearsals begin, and the show is in danger of folding before it opens, Abner agrees to let the show go on; while Dorothy, initially angry and jealous after being replaced by newcomer Peggy Sawyer, instead gives Peggy a stirring speech of encouragement before Peggy goes on stage as her replacement after Dorothy falls and breaks her ankle. And, too, there is Marsh’s stirring speech to Peggy as she makes her debut: ‘Two hundred people, two hundred jobs, two hundred thousand dollars, five weeks of grind and blood and sweat depend upon you … and, Sawyer, you’re going out a youngster, but you’ve got to come back a star!’

Upon agreeing to direct the show, Marsh learns that he has a heart problem and is seriously ill. As he proceeds to whip his cast into shape, rehearsing them night and day in order to open in five weeks, he is visibly ailing but carries on anyway. Physically and financially, he is in a weakened state. But he is nevertheless a strong and paternal leader who will sacrifice himself for the good of all, if necessary. In rehearsals before the show opens, Marsh emphasises the importance of teamwork and discipline (‘you’re going to work, sweat and work some more’) in order to make the show a success. At the end of the film, when the show has concluded its successful debut and the satisfied patrons are leaving the theatre, the final shot shows Marsh, alone after everyone departs, the exhausted leader who has ensured another triumph.

The production numbers within the ‘Pretty Lady’ show offered a lavish spectacle that appealed to Depression audiences. Importantly, no stage production could ever hope to achieve the kind of elaborate spectacles supposedly taking place on a theatre stage in 42nd Street. Berkeley’s production numbers are made for film viewers, not theatre spectators. The camera moves freely from the perspective of the theatre audience in the story to bird’s-eye views of the dancers, creating visual patterns that sway and reconfigure, and which could be appreciated only from above. The film also uses other cinematic as opposed to stage techniques to create its opulent spectacles. When Peggy and Billy kiss in the ‘Shuffle Off to Buffalo’ number, the chorines appear suddenly behind them as a result of film editing, not stagecraft. At the conclusion of the number the camera tracks through the spread legs of the chorines, a perspective unavailable to the audience in the film supposedly watching this performance. In the climactic number, the eponymous ‘42nd Street’, there is a cut from Peggy singing and tapping a solo on the roof of an automobile to an elaborate street mise-en-scène that was not there in the shots before.

Berkeley’s production numbers are perfectly suited to the theme of the story. Just as the characters must pull together for their mutual effort to succeed, so all the chorines in the production numbers have to perform in synchronisation for the visual effects to work. Emphasising the importance of geometric patterns and shapes, Berkeley’s drill team-like dance routines, as with the ‘Pretty Lady’ show itself, require both individual and group effort. Thus, both the genre’s backstage narrative and the musical numbers present a message of group unity. In the film’s historical context, the show that must be, and is, successfully put on becomes a metaphor for getting the country ‘back on its feet’. Peggy’s successful rise to stardom is a variation of the Horatio Alger success story of rising to the top through pluck and luck; also, in putting on the show, the dancers’ vitality of motion might be said to equal the dynamic energy of the American spirit, and the lavishness of the production numbers themselves an affirmation of the American Dream.

***

The Golden Age of the Hollywood musical is generally considered the 1950s, when many musicals, particularly those produced by MGM’s Freed Unit (named for producer Arthur Freed), grew more sophisticated in integrating plots and musical sequences. In It’s Always Fair Weather (1955), for example, sparring smoothly segues into choreography in the ‘Stillman’s Gym’ number, and the ‘Situation Wise’ number grows organically out of the verbal rhythms of the advertising executives’ jargon. Yet only a decade later the production of musicals in Hollywood dropped drastically. The downturn in big-budget musicals during this period can be linked to the widening gap between the kind of music used in the musicals that the studios were producing and the music that an increasing percentage of the movie-going audience was actually listening to – rock ’n’ roll (Grant 1986).

The Girl Can’t Help It (1956), the first big-budget Hollywood musical with rock music, contains a prologue in which star Tom Ewell appears as ‘himself’ and, speaking directly to the camera, explains that the film we are about to see is a story about music – ‘not the music of long ago, but the music that expresses the culture, the refinement, the polite grace of the present day’. On the word ‘culture’, the camera pans right to bring a jukebox into centre frame with Ewell; at the end of the sentence, Little Richard’s raucous title tune begins on the soundtrack and the camera tracks into the jukebox, which glows with a red-hot intensity. The song overwhelms the more sedate classical music that precedes it on the soundtrack, as well as Ewell’s adult, authoritative narrator. This pre-credit sequence of The Girl Can’t Help It is a telling expression of the generation gap engendered by the new post-war youth culture of the 1950s. Little Richard’s title song refers to the hypersexualised Jerri Jordan (Jayne Mansfield), who causes the milkman’s bottles to pop open and overflow when he sees her walking down the street. The association of rock music with sexuality and unleashed libido seemed antithetical to the romantic and communal syntax of the Hollywood musical, but as the trajectory of Elvis Presley’s film career shows, the genre was able to absorb and defuse rock music of its more primal connotations.

Pennies from Heaven (1981) is a refined or intellectual stage musical that, in its awareness of popular music’s sexual ideology, could exist only after rock ’n’ roll. The film professes a more frank view about desire than ever expressed directly by earlier popular music, yet does so by using that very music in sometimes wildly inappropriate contexts. Most obviously, characters sing male and female parts regardless of their gender. The songs are all actual recordings of 1930s popular vocalists like Connie Boswell, Bing Crosby and Rudy Vallee, with the actors lip-synching. This postmodern juxtaposition, which shatters the illusion of the musical’s utopian plentitude, is central to the film’s theme, the influence of pop culture on our individual and collective consciousness.

The film’s plot involves Arthur (Steve Martin), a sheet music salesman who believes fervently in the American Dream. Living in a stultifying marriage with his wife Joan (Jessica Harper), Arthur falls for and seduces a schoolteacher, Eileen (Bernadette Peters). Becoming pregnant, Eileen loses her job, leaves home and becomes a prostitute in order to survive. Arthur spends his wife’s inheritance on a record shop, but the business fails and, meeting Eileen again by chance, they decide to leave town together. Circumstantial evidence causes Arthur to be arrested, convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a blind girl. The ending is somewhat ambiguous but Arthur’s inexplicable happy reunion with Eileen after being led to the gallows may be understood as his final (dying?) fantasy, yet another determined by Arthur’s belief in the romantic vision of the pop songs he had sold.

A salesman, Arthur, ironically, has himself been ‘sold’ on the sunny ideology of Depression-era pop music – the impossibly optimistic view that every cloud has a silver lining and that every time it rains, it rains pennies from heaven. Embracing, like the title song, a staunchly upbeat perspective, Arthur’s imagination transforms an itinerant musician, known as Accordian Player (Vernel Bagneris), from an awkward stutterer to an eloquently expressive dancer, his cloying subservience now the fluid dance of a free spirit in the title number. When the sequence begins, the roadside café where the two men are eating opens up like the Pullman Porter in 42nd Street, but only Arthur notices.

A fervent romantic, Arthur imagines the production number ‘Did You Ever See a Dream Walking?’ when he first sees Eileen in a music shop. Later, Arthur and Eileen go to the cinema, where they watch Astaire and Rogers in Follow the Fleet (1936). Arthur becomes transfixed by the film couple’s romantic allure, and he and Eileen appear on the stage beneath the screen, dancing in perfect harmony with the towering images of Fred and Ginger in the ‘Let’s Face the Music and Dance’ number (the lyrics taking on a more ominous undertone for Arthur, who is soon to be arrested). Then, suddenly, Arthur and Eileen are ‘in’ the number, as Fred and Ginger, in a marvellous reconstruction of the original scene that suggests the way we project ourselves into the fantasy worlds of movies (and as Arthur also does with song).

If earlier Hollywood musicals sought to integrate story and production numbers into a unified work, Pennies from Heaven emphasises dissonance between narrative and music. Most obviously, the voices are only lip-synched, not the voices of the actors on screen. (Ironically, this gives Pennies from Heaven a greater truth than most musicals, in which the actors lip-synch their voices – or someone else’s – with the sound recorded at another time and mixed in later.) The production numbers are all contextualised as fantasies of the characters, and the film’s plot emphasises the disparity between pop culture fantasies and the harsh realities of Arthur’s noirish world. When, for example, the bank manager refuses Arthur a loan to start his business because he has no collateral, suddenly the musical sequence ‘Yes, Yes’ (‘My Baby Said Yes, Yes Instead of No, No’) begins. The song’s insistent positivism is a denial of Arthur’s rejection by the banker, and the choreography includes the two of them happily dancing together along with a line of tellers cheerfully bestowing sacks of money upon Arthur. At the end of the sequence we see Arthur in his car, riding home dejectedly after being denied a loan at the bank.

Figure 5 Pennies from Heaven: yes, yes, instead of no, no

Arthur insists that ‘songs tell the truth’, but life as envisioned by Pennies from Heaven is hardly the romantic fantasy offered by the Astaire-Rogers musicals. A billboard advertising a movie entitled ‘Love before Breakfast’ looms in the background by the bridge where several fateful events take place in the story for Arthur, but Arthur’s marriage is loveless at any time of day – or night. While in earlier musicals singing and dancing tends to express love and joy, Joan sings ‘It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie’ in response to her cheating husband, making Dolly Dawn’s original vocal sound much more ominous while imagining stabbing Arthur in the back with a pair of scissors. At the nadir of Arthur’s relationship with Eileen, the couple are in a seedy hotel room, Arthur wearing a T-shirt like Burt Lancaster in The Killers (1946) and I Walk Alone (1948), the hotel’s neon marquee blinking on and off. The mise-en-scène here, borrowed from film noir, stands in stark opposition to Arthur’s brightly-lit musical fantasies.

The disjunction between Arthur’s imagination and the real world shows how torn Arthur is between his own animal desire and the romantic visions of popular song. Arthur vacillates between idolising Eileen and regarding her as a sex object. Not knowing how to distinguish his fantasy from reality, Arthur is in a way as blind as the blind girl he meets, tellingly, in a tunnel. Measured against the classic musicals of the 1930s–1950s, Pennies from Heaven might be described as an anti-musical, but that is only because it works oppositely from classical musicals. If musicals conventionally use musical numbers as fantasies of sublimated desire, Pennies from Heaven employs its music to reveal how the fantasies of popular music do so. The film’s unconventional staging of its musical numbers distances viewers, preventing them from escaping into the musical’s typically appealing illusionary world as Arthur, the model cultural dupe, escapes into popular song.

Case Study: The Horror Film – Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Night of the Living Dead

Apart from the western, there has been more written about the horror film than any other genre. Of all this work, undoubtedly the most influential has been that of Robin Wood. Combining aspects of Marxist, psychoanalytic, feminist and structural analysis, Wood proposes an elegantly simple dramatic structure as the core of the genre: they are ‘our collective nightmares … in which normality is threatened by a monster’ (1979b: 10). He sees the genre as an articulation of the Freudian notion of the return of the repressed: that is, the horror film expresses cultural and ideological contradictions that otherwise we deny. For Wood, the subject of horror is ‘the struggle for recognition of all that our civilisation represses or oppresses’. The source of horror, the monster, is thus the Other in the sense used by Barthes: that which we cannot admit of ourselves and so disavow by projecting outward, onto another. Wood provides a list of specific Others in the horror genre: women, the proletariat, other cultures, ethnic groups, alternative ideologies or political systems, children and deviations from sexual norms (1979b: 9–11). All of these have been taken up by critics of the genre over the last three decades, although the last category – deviations from sexual norms – has been the one most frequently explored.

Wood’s usefully concise definition allows him to identify horror’s primary binary opposition as one between the monstrous and the normal, and to suggest that the ideological position in any given horror film is expressed by the relation between these two terms. It is in this relation that each horror film defines what is ‘normal’ and what is ‘monstrous’. Broadly speaking, conservative films endorse the ideological status quo, literally demonising deviations from the norm as monstrous; by contrast, progressive examples of the genre challenge these values, either by making the creature sympathetic or by showing normal society to be in some way horrifying in itself, problematising any easy distinction between normal and monstrous.

Most horror films are consistent in defining normality as the heterosexual, monogamous couple, the family, and the social institutions (police, church, military) that support and defend them. The monster in these films is a projection of the dominant ideology’s anxiety about itself and its continuation, but disguised as a grotesque other – what Wood calls the inevitable ‘return of the repressed’. Many horror movies tend to allow spectators the pleasure of identifying with the monster’s status as outsider, but ultimately contain any potentially subversive response by having the monster defeated by characters representative of social authority. In the terms of one of the genre’s conventions for expressing this ideological dynamic, victorious human heroes gaze at the destroyed remains of the monster and ruminate with seeming profundity that there are certain things that man is not meant to know.

In Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (1897), the vampiric Count clearly represents an unleashed sexuality that was strongly repressed during the Victorian era, when the novel was published. Subsequent film variations of the vampire have accommodated a wide range of interpretations, including fascism (Mark of the Vampire, 1944), Marxism (Andy Warhol’s Dracula, aka Blood for Dracula, 1974) and race (Blacula, 1972; Vampire in Brooklyn, 1995). But it is the sexual aspect, whether in the buxom victims of Hammer Studio’s Horror of Dracula (1958), the seductive romanticism of Frank Langella’s Dracula (1979) or the lesbian vampire movies like Daughters of Darkness (1971) and The Velvet Vampire (1971), that has been the dominant preoccupation of vampire movies.

This is the emphasis, for example, of the most famous of vampire movies, Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931). The film, based on the play (1927), in turn based on the novel (1897), today seems rather stage-bound, the special effects unconvincing (in his bat form, Dracula never seems more than a rubber toy dangling on a wire), and much of the action, including the climactic death of the vampire, takes place off-screen. Its vision of the normal, the monstrous and their relation is equally as schematic, but Bela Lugosi’s incarnation of the undead Count in Dracula, first on stage and then in Universal’s classic film, has become the familiar icon of the movie vampire. Dracula’s foreign accent, along with his aristocratic bearing and title, renders him as Other, a more monstrous version of the lustful nobleman familiar from English literature since Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740).

In the plot, after an eerie ride through the Carpathian mountains in eastern Europe, Renfield (Dwight Frye) arrives at castle Dracula to complete a London real estate deal with Count Dracula. Renfield is turned into one of Dracula’s thralls, protecting him during his sea voyage to London, where upon arrival Dracula attacks young Lucy Weston (Frances Dade), turning her into a vampire. Dracula is a sexual seducer who slips by night into young women’s boudoirs and transports them with his erotic kisses. When Dracula next turns to Lucy’s friend Mina (Helen Chandler), her father calls in a specialist, Dr Abraham Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan), who deduces that the mysterious Count is in fact a vampire. In the film’s climax, Van Helsing, with the help of Mina’s fiancé, John Harker (David Manners), tracks Dracula to his lair and destroys him.

In Dracula Van Helsing, far from the superhero makeover he received for Van Helsing (2004), is a benevolent figure of paternal patriarchy. A man of science, he uses deductive logic to determine that a vampire is at work, and combines it with action, enlisting the young hero Harker to help him destroy the threat of the vampire, tracking him to his own lair. The creature is destroyed and phallic sexuality staked in favour of monogamous heterosexuality. In the film’s final shot, with Dracula now finally able to rest in peace, the young couple ascend a long staircase to the heavenly light of day, accompanied by the promise of wedding bells on the soundtrack as the final fade-out suggests they will live happily ever after.

***

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), like Dracula, also raises issues about women and their growing independence, but the film’s focus is more on contemporary social and political concerns. By the 1950s, the real and potential horrors of the nuclear age and Cold War anxieties made Stoker’s middle-European Count seem somewhat dated. Recalling Cawelti’s discussion of 1970s genre films, Wood suggests that in today’s more sexually liberal society the conventional vampire should be discarded as an anachronism (1996: 378). Many movie vampires have appeared since 1983 when Wood originally urged that the undead Count be allowed to rest in peace, but more appropriate to the terror of potential nuclear and biological annihilation are apocalyptic visions of undead legions, as in Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Night of the Living Dead. These horror films exploit Stoker’s association of Dracula with the plague or contagion (shown in Nosferatu (1922), but not in Dracula), but imagine the infection on a national rather than personal scale. In Invasion of the Body Snatchers, all of society is threatened with emotionless replicas, zombie duplicates that, like vampires, consume our minds, bodies and souls. At a time when Americans felt particularly threatened both from within and without, the film offered a horrific yet ambiguous metaphor of the monstrous as both communist infiltration and creeping conformism.

The story is told in flashback by a wildly dishevelled doctor, Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy), to another doctor and a psychiatrist in a hospital emergency room. Dr Bennell explains that upon returning home from a conference to his small town of Santa Mira, he stumbled upon what at first seemed a strange mass delusion whereby people were having paranoid fantasies that their friends or family members were imposters. His old flame Becky (Dana Wynter), now divorced, returns to town and they go out on a date for dinner, but are interrupted when his friends Jack (King Donovan) and Teddy (Carolyn Jones) telephone, urging Miles to come to their house, where they find a mysterious, half-formed body that bears an uncomfortable resemblance to Jack. The next morning the two couples discover replicant bodies of themselves popping out of large pods in Miles’ greenhouse. Splitting up, the couples try to escape, but Miles and Becky end up doubling back and hiding in his office. The following day Jack, now a pod person, shows up with other pod replacements to detain Miles and Becky until they fall asleep. The two manage to escape and hide out from the pursuing townsfolk in an abandoned mine shaft, but Becky falls asleep, becomes a pod, and alerts the entire town to Miles’ whereabouts. He flees to a nearby highway, where he stands between lanes jammed with traffic shouting warnings (‘You’re next!’) to the heedless drivers and directly to the camera before a fade-out returns us to the present, where Miles has been telling his story in the hospital.

Director Don Siegel wanted to end the film here, but Allied Artists forced him to add the narrative frame that makes the story a flashback. In the added ending, Miles finishes telling his story, convincing his listeners only of his insanity, but at the last minute an injured truck driver is wheeled in for surgery as the paramedics explain that he was coming from Santa Mira and was buried under some weird looking pods. Now believing Miles, the psychiatrist (Whit Bissell) instructs the staff to get the FBI and the President on the telephone. This imposed ending may seem upbeat, but in fact does not provide the comfortable closure of a horror movie like Dracula. For how could the FBI or anyone possibly contain the pod invasion, which by now has spread much wider than the town of Santa Mira? The film’s ending is considerably more ambiguous than the ending of Jack Finney’s source novel, in which Miles sets fire to a field of growing pods, forcing those that do not burn to rise into the sky and retreat from Earth.

Figure 6 Invasion of the Body Snatchers: alien pods threaten domestic space

The ambiguity of the film’s ending is indicative of its ambivalence towards the normal and monstrous. The pod people are a horrific, emotionless Other bent on destroying humanity. Like the giant ants in Them! (1954), the emotionless pod people (‘No more love, no more beauty, no more pain’) work for a collectivist mentality that threatens to undermine America. The pod people gather in the town square, brought together by some silent signal, to spread the conspiracy by taking pods to nearby towns and cities. Yet at the same time, the pod people are only horrific exaggerations of the alienation of modern American life: as Miles observes while hiding in his office, ‘In my practice I’ve seen how people have allowed their humanity to drain away … We harden our hearts. Grow callous.’ In the climax, everyone in town pursues Miles and Becky up the long stairway into the hills as the town warning siren blasts ominously. The crowd searches out dissenters like Miles, recalling the HUAC witch hunts of a few years earlier. The relative proximity of the highway, when Miles finally reaches it, provides an extra horrific twist by enacting this nightmarish invasion so close to the flow of civilisation. The cars are bumper-to-bumper, the drivers oblivious to what is going on around them, already alienated in their rush to nowhere.

The film makes the mundane seem menacing, as in the scene where Miles and Becky visit her cousin Wilma (Virginia Christine), who is convinced that her Uncle Ira is no longer her Uncle Ira. Nothing dramatic happens, but Ira is shown in a slightly canted image, suggesting that something is off kilter as he goes through the banal motions of mowing the lawn and chatting idly about the weather. Even before Psycho, Invasion of the Body Snatchers revealed the horrors of the quotidian world. The film begins in sunny southern California but grows darker and more threatening, a movement paralleled by the increasingly smaller spaces in which the characters are placed, from Becky’s basement to the closet in Miles’ office to the hole in the ground in the mineshaft. The image of Miles and Becky running down an alley in the dark of night, looking for a place to hide, evokes such classic ‘outlaw couple’ noirs as You Only Live Once (1937) and They Drive by Night (1949). As in It’s a Wonderful Life, the town changes from a Norman Rockwell vision of idyllic small-town America to a noirish nightmare.

***

Drake Douglas explains the derivation and the original power of the zombie, the only important movie monster of legendary proportion to emerge from the New World, as a horrifying image for enslaved blacks in America and their consequent loss of volition in perpetuity (Douglas 1969: 158–71). This meaning is invoked in the first important zombie movie, White Zombie (1932), when one of the undead workers is crushed by the grinding apparatus of a sugar mill as the rest unflinchingly carry on with their tasks, grist for the mill of capitalist exploitation. More contemporary zombies have figured as metaphors of modern crowd behaviour (Waller 1986: 279), a direction initiated by George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968 and taken to comic extreme in Shaun of the Dead (2004) and Fido (2006). Night of the Living Dead reverses many conventions of the genre and, perhaps because it was made independently, outside of Hollywood, boldly depicts normality itself as unambiguously monstrous. Romero’s independently-produced film has been extraordinarily influential within the horror genre, spawning three sequels (Dawn of the Dead, 1978; Day of the Dead, 1985; and Land of the Dead, 2005), numerous imitations and establishing a new monster mythology.

Night of the Living Dead begins with brother and sister Johnny (Russell Streiner) and Barbara (Judith O’Dea) driving in their car for an obligatory visit to their father’s grave in a rural cemetery. Suddenly they are attacked by a ghoulish figure in the graveyard. Johnny is overwhelmed by the attacker, and in a state of shock Barbara manages to escape to a nearby farmhouse. Soon she is joined by Ben (Duane Jones), also fleeing from the ghouls. After fighting off several zombies and boarding up the doors and windows of the house, they discover several other people hiding in the basement: Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman), his wife Helen (Marilyn Eastman) and young daughter, Karen (Kyra Schon) – who has been bitten by one of the zombies – and a pair of teenage lovebirds, Tom (Keith Wayne) and Judy (Judith Ridley). Harry and Ben disagree over whether to escape or barricade themselves in the basement, eventually trying Ben’s plan, but Tom and Judy are killed when the truck they attempt to fill with gas explodes, and their charred remains are consumed by the zombies. Harry thinks only of his family, endangering the others as a result, and in a power struggle and scuffle over a rifle Ben kills him. Karen turns into a zombie, kills her mother and is shot by Ben, who then seals the basement door, preventing the zombies from entering. In the light of morning Ben emerges from the basement, only to be shot by a member of a vigilante group moving through the area trying to clear it of zombies.

The film consistently violates generic convention. Unlike most earlier horror films, in Night of the Living Dead the horror begins immediately, and in the daytime rather than at night. The death of the endearing teenage couple violates the conventions of numerous earlier monster movies, such as The Blob, where the young couple live to warn adult civilisation. Ironically, the basement turns out to be the safest place rather than a metaphor for the subconscious terrain from which monsters usually emerge, as in Psycho. Night of the Living Dead features the conventional scenes of conferences between the military and scientists as civilisation marshals its forces against the monstrous threat, but here the authorities are bumbling, evasive and confused as the news camera vainly pursues them for information. Untypically, the hero is black, which gives the tension between Harry and Ben added resonance. Although the newscast on the farmhouse television suggests a possible explanation for the zombie phenomenon (radiation brought back to Earth from a space probe is reanimating the corpses of the recently deceased), no definitive explanation is ever provided, and ultimately the various institutions (social, religious, military) that defeat the monster in earlier horror films offer no such salvation in Night of the Living Dead.

Robin Wood argues that cannibalism ‘represents the ultimate in possessiveness, hence the logical end of human relations under capitalism’ (1979b: 21). From the beginning of the film there is a clear attack on American society: in the first scene Johnny and Barbara are driving through a cemetery with an American flag in the distance, offering at the outset a chilling image of the pervasiveness of death in American culture. Such imagery was particularly resonant in 1968, during the height of the Vietnam War. Instead of the sense of national community and pride for the flag depicted in Drums Along the Mohawk (discussed in the next chapter), the America of Night of the Living Dead is marked by death. Tellingly, the zombies are dressed like average folk from all walks of life – that is, middle America. As represented by the bellicose Harry Cooper, the film also attacks the nuclear family, the very institution valorised in the happy ending in Dracula.

When, in the end, the sheriff’s marksman shoots Ben, it would seem that they cannot tell for sure whether the figure in the house is alive or undead. This is a troubling ambiguity, given that Ben is black and that the vigilante group seem like stereotyped rednecks. The film was made during a period of violent racial tensions in America in the late 1960s. Its grainy black-and-white imagery may have been the result of the film’s rather small budget compared to the typical Hollywood feature; however, it adds to the film’s power by evoking a cinéma vérité-like realism similar to contemporary television news footage of combat in Vietnam and civil rights strife at home. Because the hero is black, the final montage of still images of Ben’s body being thrown on a large pyre, his body handled with meathooks, suggests news photos of beatings and lynchings in the American south at the height of the Civil Rights movement. The sheriff’s comment, ‘another one for the fire’, resonates with the fear of racial violence that had erupted in many American cities around the time of the film’s release. Whereas an earlier horror movie like Dracula presents the normal as unquestionably good and just, and the vampire unwaveringly evil, Night of the Living Dead shows normal society (those on the ‘inside’) as monstrous and as much of a threat as the zombies on the outside.