During the previous few years, it hadn’t simply been my desire to spend time with my parents that led me to make more trips cross-country. Instead, a protracted illness plaguing Mom for “just too long” or an unexpected angiogram that Dad needed were the specific factors that motivated me to leave home in Southern California for New York City, especially during the bracing winter months. Even then, my visits to see Mom and Dad were neither as habitual nor as frequent as they would soon become.

When I came to town that life-changing December, it had only been a matter of months since I’d seen them last. Ever since I’d left home for college, my parents had always been so excited to see their only child that they would come and pick me up from whatever airport I flew into rather than wait for a taxi to deliver me to their apartment. But this visit, in the freezing night air, no one was at the airport for me.

Not only was there no warm welcome, but when I called them on the phone from the hotel where soon I would become a regular, Dad was curt, monosyllabic, and distant. That was so unlike him. Also, sounding extraordinarily exhausted, he tried putting off getting together for dinner until the last possible moment. It seemed as if Dad wished I would cancel the evening entirely.

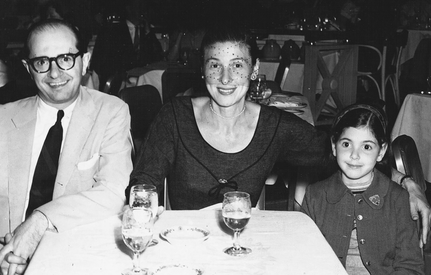

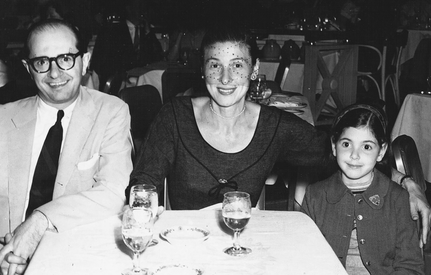

When I finally met up with Lillian and Jack Wolf at a cozy neighborhood restaurant that unnerving evening, I didn’t recognize the old, worn-down couple in front of me. Having always known her to be a perfectionist, Mom’s appearance was shocking. She looked like someone had pulled some old dress from the back of her closet and stuffed her into it. Mom’s customary hairstyle—immaculately combed and carefully organized into a white-haired bun—appeared to have had a comb half-heartedly dragged through it. My hitherto elegant mother would never have let herself out of the house looking like that.

In other ways too, she was a shadow of her former self. Mom’s breathing was clearly labored as she dragged herself to our table at a glacial pace. When I kissed her cheek, her skin was eerily cold to the touch. My sense was that she was icy from the inside all the way to the surface, not merely chilled by the cold temperatures outside.

Earlier in the week, when we’d spoken on the phone, I detected nothing unusual, but the woman in front of me could hardly formulate whole sentences. She had difficulty following our conversation and couldn’t focus on the ordinary restaurant tasks of reading a menu and ordering. When she allowed Dad to order her meal and then speak for her, I knew something was seriously amiss. My “real” mother would never have heard of such a thing.

Dad was acting nothing like his normal self either. He radiated fatigue of such a deep nature that no amount of sleep looked like it would restore him. When I was still back in L.A. talking to him long distance, his voice had been able to deceive me. He had successfully concealed this complete exhaustion—physical, emotional, and mental—but now in person, I could see the true nature of his condition. One of Dad’s signature characteristics was his fascination with life’s details and his daughter; in my dating years, often I’d had to pry my boyfriends away from talking to him. But that night, Jack showed little interest in anything.

As I lay tossing and turning in bed later that night, I couldn’t deny that there was something very troubling going on. I’d wanted to chalk up my parents’ disturbing ways to “a bad evening.” Certainly, we all have them, I told myself. But I just kept thinking: Who stole my parents? Who were these doddering people?

I tried playing detective by thinking back to their histories. Generally, Mom had been as healthy and energetic as women years younger. However, a few years before, she’d contracted a case of pneumonia serious enough to require hospitalization. During that stay, some attending doctor while conducting rounds informed me by long-distance telephone that Mom had dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. It was a diagnosis I’d questioned at the time due to the tests he’d used and other factors, like her being disoriented in an unfamiliar hospital setting. But lying in bed, I wondered if what I was seeing now could be Alzheimer’s?

In 1974 I moved to California from the East Coast, where I’d been raised and schooled. By the time I made this holiday visit in 1997, I’d lived out West for nearly twenty-five years. I was approaching middle age and my parents were each eighty-five. Although I’d seen aspects of Mom’s memory dimming during earlier visits, I was shocked when that doctor broke the news to me of his medical opinion. Watching her work her beloved crossword puzzles for many years following this diagnosis supported my suspicion that it had never been properly determined.

However, on this sleepless night of searching for a reasonable explanation of her bizarre behavior, I feared that Mom was finally “showing her Alzheimer’s.” Understanding the slow and progressive course of the disease as I did from years of working as a geriatric therapist, I soon ruled out that dementia had suddenly descended on my poor mother. It wasn’t possible that she had declined so rapidly as to need institutionalization, between the time on Monday when she’d talked lucidly on the telephone and Friday when I saw her in the restaurant. There must be something else going on. As for Dad, I thought that perhaps he too had gotten sick while caring for and worrying about Mom. I was troubled by his appearance and lack of spirit as well.

My most pressing problem was to discover what was causing them to seem so unlike themselves—so very old and needy. The next morning, bleary-eyed from lack of sleep, I called to arrange to have breakfast with them. Dad put me off, postponing our getting together that day completely. “Mom’s still under the weather,” he said casually. “Go enjoy your friends and the wonderful show at the Met.” The following morning, I called again and got more excuses. In fact, Dad seemed more determined than ever that I stay away.

A part of me wanted to obey him and let them rest alone. But another part just couldn’t do the “good daughter” thing and comply, because something wasn’t right. Once I’d made up my mind that I needed to see for myself what was going on, the taxi-ride across town seemed to take forever. The look on my father’s face when he opened the door to their apartment, and his cold stare were both foreign to me: “I told you not to come. What are you doing here?” Once inside, the sight left me in shock, stone cold. It wasn’t long before sad and even mad joined the emotion of shock.

My mother, always so attentive to the appearance of her home, herself and her things, had allowed their apartment to become caked with dust. I quickly calculated that that much dust must have taken a while to accumulate. I learned as I walked in that my folks had gotten rid of their longtime housekeeper at a time when they particularly needed someone to clean and cook for them. Nostalgically, I remembered how Dad used to joke that Mom was so neat “she’d make the bed in the middle of the night, even before I returned from the bathroom.” That seemed like a lifetime ago.

Heading into their bedroom, I saw that my venerable parents were sleeping in sheets that had turned a deep gray from their original white. Neither of them had taken a bath in several weeks, as it turned out. Mom had been too weak to navigate the tub and Dad was afraid to leave her alone long enough to bathe himself. Predictably, their moods were equally low. Mom was confused, alternately passive and then aggressive, even lashing out violently if she felt she was being challenged.

Dad seemed deeply disturbed, not only by his own fatigue, but perhaps more pressingly by his inability to care for his sick wife and whatever meaning he was attaching to that. It all seemed to be dangerously depressing him. I finally understood why my father hadn’t wanted me to come over. They both had been hiding from me the extent of their medical conditions, their home, and their need for help! In that moment, I feared for all of us, for myself as well as for them. Things had gotten totally out of control and someone needed to straighten them out.

There was no one but me. I had no siblings or even close friends who lived near enough to enlist for the type of help I was now envisioning my parents were going to need. I previously had no plans to stop working; quite the opposite, as I had just started my second career thousands of miles away. Although surrounded by my clearly dependent parents, I suddenly felt alone. And in spite of my years of seemingly relevant education and experience, I was lost and panicky.

I saw that I’d been pretty much ignoring the fact that someday my parents would need help. I had been reluctant to ask them important questions until this crisis forced me to. Up until that visit, I had avoided looking ahead and had made no plans for my parents’ future. Now I needed to do a lot of fast thinking and catching up. My New York vacation had been scheduled to end in three more days, when I was slated to return to my life in California.

What life? My life—as I’d known it up until then—seemed like it was about to be altered forever. Slowly I saw there were significant choices I would need to make. Would my attention, time, and resources become increasingly trained on my parents? It seemed I might be choosing to honor and preserve the threesome my life had begun with or that “’til death do us part” might refer to my new relationship with my parents. I might even have to contemplate parenting my own parents as my commitment grew over time.

Was I ready and willing to parent my own parents? They seemed to need something different from me than I’d ever considered before. If I decided to care for Lillian and Jack, I might have to give up many of my previous pictures of how my life was supposed to be. I would need to make important decisions, maybe different ones than I’d previously expected.

I didn’t yet know that I would find myself maneuvering through complicated role reversals, balancing my need for my parents’ safety with their independence, and discovering how to honor both their wishes as well as my own. I couldn’t even imagine how long caring for my parents might last or what kinds of changes I would need to face. Nor did I realize at that moment that I’d remain on call and never leave a phone unanswered for the next ten years lest I miss an urgent call from my parents or their doctors.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. On that freezing December morning that marked the birth of our family’s POPcycle, there were no tree ornaments or other symbols to suggest any festivities at the Wolf home. Instead, that morning initiated an intense nostalgia, as the girl in me longed for the old days, when things were fine. It felt like I was going through the rigors of birthing a new phase of my life. Maybe more importantly, in that moment, it felt like death—the end of an era.

If I were to take on this challenge, Lillian, Jack, and I would need to reverse our roles. I would be caring for them this time around. That Christmas, we were beginning our last journey together, through a cycle that would be unidirectional and irreversible. I could see ahead enough to imagine the way it would go: my parents would inevitably become increasingly unable to care for themselves and the details of their lives. They would become more and more dependent on me. Simultaneously, I would become more and more responsible for them, making more and more of their decisions and acting increasingly parental.

Since Lillian had started coughing and wheezing, maybe two weeks earlier, she had become weaker and was acting more bizarrely each day. I too had come down with something physically unpleasant, a tickle in my throat and some sneezing, but I avoided taking my temperature. Instead, I just kept popping aspirin. I saw it as my responsibility to look after Lillian, after all I always had.

When we’d first met, taking care of Lillian had been all I’d wanted. Our fit seemed a natural. Not only was she a strikingly beautiful and smart woman, she was also the youngest in a family of six, vulnerable from having lost her dad as a mere girl of five. I was the eldest son and I had always protected my younger brothers—organizing the boys, making sure everyone had enough food and pocket money and that their homework was done. My father didn’t pay that much attention to us kids. That was the way at the time. My mother was absent a lot, having been a political activist and a newspaper columnist. So, I learned to do a lot of family caregiving from the time I was fairly young. Probably it was also in my nature.

I had thought that looking after Lillian now, with her coughing and weakness, would be fairly simple. I’d bring her what she needed—some aspirin, something to help her breathe better, some chicken soup—but nothing I did was helping her much. My wife seemed to be getting worse rather than better. I didn’t really know what to do.

As Lillian’s physical condition worsened, her behavior also became increasingly irrational. She had been insistent that I not tell Jane how ill she had become. When I suggested we invite Jane over to help us since she was in town, Lillian’s response had been immediate: “Absolutely not! She’ll just want to come in here and tell me what to do,” Lillian had cried. I didn’t know what to do but decided to keep my wife calm by agreeing with her. Usually that worked.

The night we met Jane for dinner at the restaurant was our first venture out of our apartment in some weeks. It took a lot out of both of us. For days we hadn’t really bathed or changed our clothes very often. I didn’t have enough strength to lift Lillian high enough to get her into or out of our bathtub although we both did need to wash, after a while. When I reached the point where I knew I needed to bathe, I was afraid to leave her alone long enough to run my own tub and soak there. So, I just kept waiting, thinking eventually it would all pass and things would return to normal. I was so exhausted I often couldn’t sleep. My body and mind were beyond any fatigue I’d ever known, or at least as I can recall at this point.

In order to go out to meet Jane for dinner, I’d been forced to get some clean clothes on Lillian and myself and to straighten her hair out as well. She would barely let me put a comb through her beautiful white hair, generally perfectly organized, but that night it looked all ratted up and silly. I have hardly any hair of my own, so tending hers was not something I did well. Dressing her was another matter. I found a dress in her closet that she used to like wearing, but she wasn’t very cooperative. When I was done, she looked amazingly disheveled, as if someone had poured her into someone else’s dress. I thought to change her but didn’t have the energy to start all over again.

I know Jane was taken aback that first night when she saw us both, especially Lillian. My approach was just to get us through the evening—order for Lillian, eat, and make some conversation. I was so stressed just trying to make everything seem normal. I was still hoping that pacifying Lillian would get us beyond this particular crisis and then we’d be able to get back home without Jane’s becoming too suspicious.

Putting Jane off for a day or two after that dinner seemed to work. But then she showed up unexpectedly at our front door, after I’d told her specifically not to come. Finding Jane there was a shock. Her mother and I had always encouraged her to have a mind of her own and I’d been proud to see her develop as a bright and independent thinker. But Jane was also an obedient girl, having given us no real trouble and doing what we’d asked of her most of the time, as far as I knew. That morning was the first time I remember her ever defying me directly. While we were on the phone I’d said clearly to my daughter: “Do not come here,” but hardly were the words even out of my mouth, she was at our door.

I wouldn’t have tried to keep the state of Lillian’s ill health or our home from Jane if it had been totally up to me. I thought Lillian’s dissembling was ill conceived, especially since Jane was coming to town and, most certainly, would observe the condition of our apartment and our health. But Lillian had always been concerned to be her own person and had some fear that Jane would take that away: she had also become increasingly paranoid as her illness wore on. I had been torn, wanting Jane to know but not wanting to upset Lillian.

And then all of a sudden, Jane was there at our door. I felt like we’d been caught red-handed. After my shock and short-lived anger retreated, I recognized that I was enormously relieved I didn’t have to hide anything anymore. The truth Jane saw was not pretty. Lillian had always been a perfectionist about her home and her appearance and a really clean person. But she had begun to let everything go. She didn’t open the mail or clean a dish. Things were just used and then left everywhere. The dust was caked on our beautiful antiques she and I had so carefully chosen years before. I understood how badly my wife must have been feeling to let everything go like this. To Jane, the current scene was the exact opposite of her childhood home: it must have been frightening.

We hadn’t changed the sheets or done laundry in a while either, so Lillian and I were sleeping on pretty badly graying sheets. Everything was becoming harder and harder to take care of. Things were piling up around us. I had taken to calling in for our meals from our favorite delis and coffee shops in the neighborhood, so we did stay fed. As for me, I was desperate to see Lillian’s special smile reappear and I would have done anything to bring it back.

Now that Jane had seen fit to defy me and show up, I knew that she would help me.

If you are fortunate enough to still have older living parents or other close loved ones who are seniors, you must have seen them change over time. Whether your attention was drawn to this slowly and imperceptibly through the years or dramatically one day, you must have seen that, after a while, even the most robust of our elders starts to slow down.

Not everyone has as dramatic or traumatic a Christmas “revelation story” as I did, thankfully. Maybe you first noticed the change when your parents uncharacteristically began asking you for advice—and then actually took it. Or maybe your folks simply started expecting you to help them with many more things, far more often than they used to. Perhaps it was your mother-in-law’s continued refusal to accept your help when she clearly needed it that caught your eye.

Maybe your mom took a fall a few months ago and even though she’s tried, she can’t really get back on her feet. Now maybe she’s having trouble going back to work and even getting to the market. Cooking, which she’d always loved, is becoming a chore. She’s feeling badly that she can’t take care of your kids on Saturdays, as she used to. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, three million older Americans are treated in ERs from fall injuries. The long-term impact of such falls can often be life changing for the senior and the family (see https://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html).

Or perhaps your wake-up call came in the form of your dad’s calling you, incensed about some man repeatedly phoning him about some unpaid hospital bill who is getting increasingly hostile. Although he doesn’t remember being hospitalized, your dad would like this bill paid just to stop the disturbing phone calls. Maybe he did pay the bill, he tells you. He’s not really sure if he’s been in a hospital recently or not, so he asks you to speak to the man for him.

Maybe your parents have recently stopped coming to Sunday-night dinners at your house. At first, they offered weak excuses, but one day your mom finally revealed: “Dad doesn’t like to drive at night anymore.” On a hunch, on your next visit to your parents’ home, you take a look at his vintage car and notice the passenger door is dented and the car has a flat tire. You understand that it’s more than night driving your father is no longer doing. You wonder if he’s been afraid to drive or if he even should. Did he have an accident? Was anyone hurt? Is there a lawsuit pending? Is he confused on the road? Is he afraid to tell you that he dented the car? Maybe he really wants you to know. You ask a few more questions and find out: “I had a small accident. I didn’t think you needed to know.”

These are the sort of telltale signs that can let you know that your parents are beginning to need some help. The people who raised you may now need you and/or your siblings or even an occasional caregiver to do a few tasks so everything can “get back to normal.” But your parents, like mine, will continue to slow down and progressively age. And eventually, if they live long enough, your parents may resemble childlike, even infantile, versions of their earlier selves. You are witnessing the final chapter in their life, the POPcycle.

As you pay further attention to these initial signs of aging and stop to evaluate your parents’ level of frailty, fragility, or even possible senility, you may also be catching a glimpse of a unique part of your own life cycle. If you also choose to parent your own parents, you will be joining a special cadre of loving people who are taking on more and more responsibility for their aging parents’ well-being.

Soon you may be taking your parents to their doctor appointments, where you may often act as their historians, truth tellers, and translators. Then you will probably find yourself interceding for your parents with Medicare and Social Security. Next, you’re getting their perhaps all-too-numerous prescriptions filled and refilled and picking up some adult diapers—since you’re already at the pharmacist. And before long, you’re paying their delinquent, “misplaced” bills and shopping for healthier food for them. And one bizarre day, soon, you may be telling the very people from whom you used to borrow the family car that they need to stop driving.

Many of you have already begun attending to your aging parents, some full-time and some part-time. Your involvement is at some point likely to become critical to your parents’ everyday living. The truth is that you and I are developing new relationships with our senior parents, ones we probably never expected we would have. Over the course of time, you are likely to become substantially involved in your parents’ lives emotionally, financially, and even spiritually. Some of you may leave your job, give up your home, and move across states to POParent your folks. Given the longevity of today’s seniors and the current offering of new medical treatments and pharmaceuticals, no matter how many years you put in to parent your children, you may end up parenting your parents for even longer.

If you choose to parent your parents, you will be joining me and countless others who’ve made the choice—to Parent Our Parents, to do POP. You will be part of the millions of loving adult children who are deciding that we wish to devote ourselves to caring for our aging relatives and making this POP time a special one for all concerned. Your realization of your parents’ neediness and your need to face this decision may be as shocking as mine was. Ultimately, you may join us in saying: Oh my God! We’re Parenting Our Parents! We’re doing POP!

Choosing to do POP at this important juncture can provide unexpected opportunities for completion and closure for you, your other family members, and certainly for your parents. How you choose to participate in this special time is limited only by your particular circumstances and your imagination. Some will make up for missed time from the past. Others will establish more intimate connections with their parents than they’ve ever had before. Still others will undo decades-long estrangements with their parents and siblings.

How will you know if your time for doing POP has begun? How might your parents display their changes to you? How can you learn to read the signs soon enough so that, hopefully, you will have figured this out before you face the kind of crisis I encountered? Will you be able to demonstrate the necessary confidence, courage, and determination to discover whether, how much, and when your parents need POParenting?

You will need a method to evaluate your parents’ needs, both at the start and then

again later. Likely you will have to do so repeatedly over your years of doing POP.

To help you better conceptualize what is happening developmentally between you and

your

parents, their growing dependency, and your increased responsibility and decision-making,

I offer you the “POPcycle” (not necessarily pronounced “Popsicle”).

You can chart the relevant factors in your senior parents’ functional dependence/independence to see when, where, and how you will want or need to increase the support and protection for your aging loved ones. It is useful to have the POPcycle as a measurement of where your parents are, since the chronological model that pediatricians use to assess your child’s development is of little value to the geriatrician or the POP family seeking to evaluate aging parents’ development.

Once you’ve done your initial assessment of your parents’ current circumstances, you will need to discover many other important things. You will either choose to jump in or else find out if there is or could be someone else to take on the job. But for that, you will want to move on to chapter 2.