Our overall policy at the present time may be described as one designed to foster a world environment in which the American system can survive and flourish…. This broad intention encompasses two subsidiary policies. One is a policy which we would probably pursue even if there were no Soviet threat. It is a policy of attempting to develop a healthy international community. The other is a policy of containing the Soviet system.

In the summer and fall of 1950 the administration of President Harry S Truman entered into uncharted fiscal territory, committing the United States to very high levels of military spending on an open-ended basis. The rationale for this move was set forth in NSC 68, one of the foundational documents of U.S. postwar national security policy, completed just a few months before the start of the Korean War. In spite of the undeclared war in Korea, both military planners and their critics understood that the successive supplemental spending proposals that nearly quadrupled the fiscal 1951 military budget were not short-term emergency measures intended exclusively for that particular conflict. Instead, these increases reflected a fundamental shift in strategy. Henceforth, large military expenditures were to remain a fixture of U.S. policy, essential both for the long-term global struggle with the Soviet Union and, beyond that, for the effort to build and maintain “a healthy international community.”

Given their understandable preoccupation with the Soviet Union, the senior administration officials who drafted NSC 68 did not spell out the military implications of policies “which we would probably pursue even if there were no Soviet threat.” This aspect of the strategy, which included the construction of a world order open for American trade and investment, especially in economically important regions, was perhaps less salient at the time. Over the long run, however, it has proven more important. The need to contain the Soviet threat ended by 1990, with the end of the Cold War. Events since then suggest that the demands of developing a healthy international community—and the related high level of U.S. military spending—may never end.

In 1950, the prospect of maintaining relatively high levels of military spending for an indefinite period of time appeared daunting. Depending on their political orientation, observers worried either that the United States might spend too much on the Cold War, or that it might prove unwilling to spend enough. For critics on the right, permanent high levels of military spending carried the risk of transforming the country into a garrison state, its wealth consumed by the cost of its international commitments, and the political and economic freedoms of its citizens compromised by exigencies of permanent war, or at least what Senator Robert Taft (R-OH) called “semiwar.”2 On the other hand, national security policy planners like the authors of NSC 68 expressed concern about the nation’s willingness to sustain the sacrifices required for a long struggle.

Because the United States had never before sought to maintain a large military force in peacetime, these concerns were understandable. They persisted throughout the Cold War. Policymakers and supporters of Cold War foreign policy never stopped worrying that cuts in spending might leave the United States or its allies vulnerable to attack or intimidation. Conversely, concerns about the implications of excessive military spending reemerged whenever the Pentagon budget rose, as it did during the wars in Korea and Vietnam, during the 1980s, and again after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

During the latter part of the Cold War, liberals replaced conservatives as the leading critics of military spending, but the critique itself did not change. The basic charge was this: by consuming an inordinate share of national resources, runaway military spending could damage the economy. It diverted investment away from more economically beneficial uses, and fueled inflation. It warped fiscal priorities, forcing tax increases or diverting funds from domestic priorities such as education, health care, and social welfare. Perhaps most importantly, permanent high levels of military spending promised to distort American politics and society, creating a constituency for militarism.

After more than fifty years of unprecedented levels of military spending, neither camp has seen its worst fears come to pass. The American people have not refused to pay the bill for global military engagement, nor has the country become a garrison state. Nevertheless, the fact that no nightmare scenario materialized does not mean that the concerns expressed by both camps were misplaced. The willingness of Americans to pay for national security policy did have real limits. Furthermore, these limits have left a lasting imprint on U.S. national security policies. Similarly, building and maintaining the force needed to carry out these policies had substantial political and economic effects, even if these effects fell short of causing economic collapse or a descent into military dictatorship. Understanding the patterns and the true implications of U.S. military spending since the end of World War II is essential for fully appreciating postwar national security policies.

PATTERNS OF MILITARY SPENDING AND

AMERICAN POWER

Understanding what American military spending purchased in the postwar era requires an appreciation of two apparently contradictory facts. First, the scale of military spending since World War II has been massive and unprecedented. Second, that spending nevertheless had its limits, with important consequences for the character of the U.S. military. A review of several important trends underscores the importance of both these considerations.

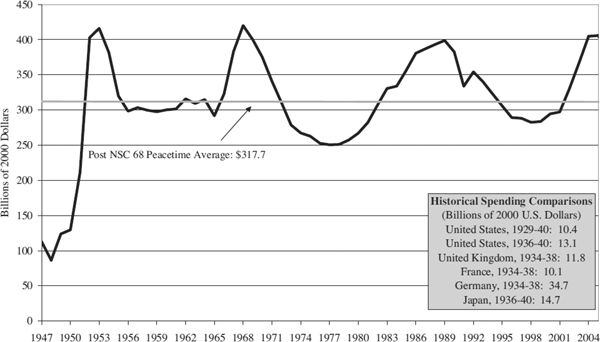

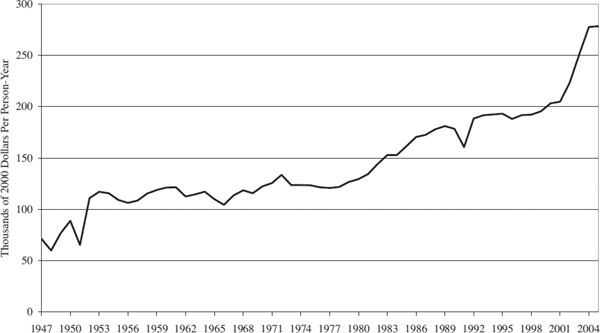

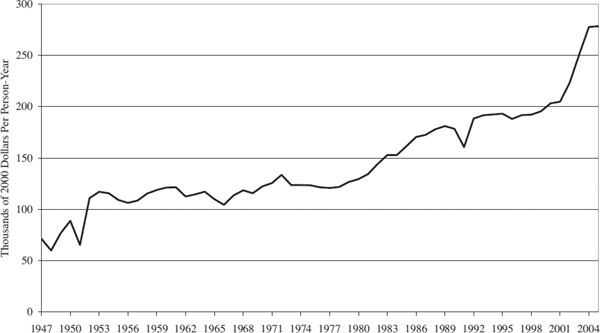

When it comes to the aggregate level of military spending, NSC 68 and the Korean War were indeed watershed events. Ever since the large spending increases of the Korean War era, U.S. defense outlays have followed a recurring pattern. Figure 9.1 shows U.S. defense outlays in 2000 dollars between fiscal 1947 and fiscal 2005. As the graph suggests, American military spending had an inertial quality, consistently returning to its post-1950 mean after major buildups or cutbacks. The major fluctuations in the series can be attributed to the wars in Korea and Vietnam, the Reagan buildup, and the reaction to the September 11 terrorist attacks. Fears that the United States might not be able to sustain greatly increased levels of spending proved unfounded. Even during periods when there was little actual fighting, such as the 1950s (after Korea), the 1970s (after Vietnam), and the 1990s, the United States still allocated far more for defense than it had during the 1947–50 period. As the graph indicates, peacetime military spending during the 1954–2002 period averaged $317.7 billion in 2000 dollars, two and a half times the $124.6 billion spent annually during the 1947–50 period.

The inset table in Figure 9.1 offers several other historical comparisons. U.S. defense outlays since World War II have dwarfed not only prior American spending but also the military budgets of other major powers in the five years before each entered the Second World War.3 The postwar peacetime average was nearly nine times what Germany spent annually as it prepared to launch World War II. Although budgets do not translate directly into military power, and these comparisons are not exact, it is clear that when compared to the military outlays of great powers up to World War II, the scale of resources the United States has dedicated to its military since 1945 is historically unprecedented.

Source: Office of Management and Budget; Correlates of War Project, National Military Capabilities Dataset

Of course, for most U.S. policymakers the demands of the Cold War had rendered historical comparisons with the 1930s irrelevant. In their view, the challenges facing the United States after 1945 were unique and the contemporary Soviet Union, not the record of earlier great powers or past American practice, provided the principal point of comparison. From this perspective, the key question was whether American military spending sufficed to maintain a force large enough to deter or, if necessary, defeat a Soviet attack on the United States or its allies. Raising and maintaining such a force formed only one aspect of this effort, of course, but it was an important aspect. If the Soviets outspent the United States for a long period of time, policymakers in Washington feared that the United States might slip into a position of pronounced military inferiority. At a minimum, compensating for such a disparity would have posed daunting diplomatic, military, and technological challenges. Using Soviet expenditures as a basis for comparison, U.S. defense outlays, while still impressive, look somewhat less extraordinary.

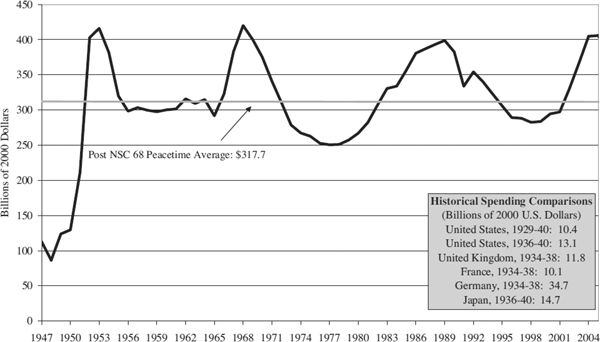

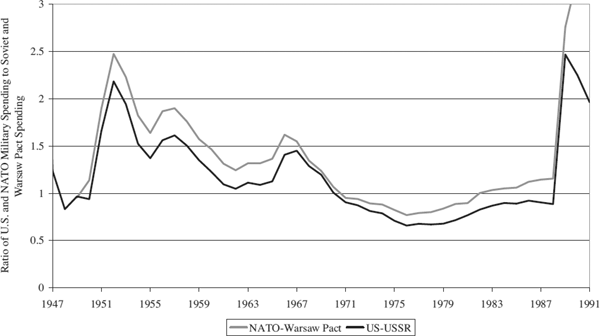

Figure 9.2 depicts the ratio of United States and NATO military spending to outlays by Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, respectively. (In the graph, a score of one indicates parity, while higher scores show an American or allied advantage.) The large jump in spending associated with NSC 68 and the Korean War gave the United States and its allies a substantial edge. Nevertheless, although American spending remained at very robust levels thereafter, the Soviet Union gradually eroded this edge, gaining a slight advantage over the United States during the 1970s, and maintaining it until the waning moments of the Cold War. As the graph indicates, the alliance system worked in favor of the United States, but did not greatly alter the overall East-West balance in Europe. Cuts in U.S. spending that followed the war in Vietnam allowed the Soviet Union to gain on the United States and its allies, a fact that helps explain growing concern among American policymakers and the general public that the United States was falling behind during the late 1970s and early 1980s.4 Although the Soviet gains were real, it is important to keep them in perspective. Through an enormous effort, the Soviets gained little more than parity with the United States. In the long run, the costs of that effort to the Soviet system proved to be enormous.5

While U.S. defense outlays appear reasonable in the context of keeping pace with the Soviet Union, the end of the Cold War created a sudden radical imbalance between the United States and all other potential military adversaries. Although some worried that China might soon emerge as a new “peer competitor,” these concerns proved unfounded, at least in the near term. Chinese military spending did rise steadily during the 1990s. Even so, the $276.7 billion the United States spent in 2002 was nearly five times the $55.91 billion the Chinese allocated. Other states identified as potential threats were at an even greater disadvantage. According to CIA estimates, Iran spent $9.70 billion on its military in 2002. That same year, North Korea and Iraq spent $5.22 billion and $1.30 billion respectively. The military expenditures of major American allies in 2002, totaling some $247.36 billion, further increased the advantage enjoyed by the West.6 These vast disparities in post–Cold War military spending reflected not conscious planning in Washington and allied capitals, but inertia. Although the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union and its empire transformed the international security environment, old spending habits persisted.

Source: National Military Capabilities data assembled by the Correlates of War Project

Accidental or not, the enormous edge in military spending had important implications for U.S. national security policy, permitting military actions that would have been unthinkable only a few years earlier. For post–Cold War administrations, the huge U.S. military advantage constituted a standing temptation—or opportunity, depending on one’s point of view—to intervene militarily in international disputes or humanitarian disasters. Continued high levels of military spending purchased capabilities far beyond what was needed to defend the United States and its allies. Activists of many different political stripes, both in an out of government, clamored to put those capabilities to work.

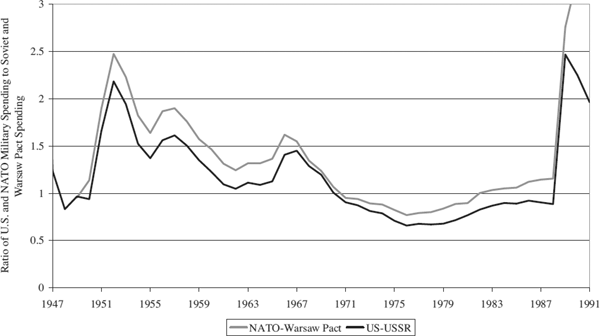

Although the post-1950 U.S. military budget remained fairly consistent in terms of real dollars, it absorbed a declining share of the nation’s overall wealth and of the federal budget. Figure 9.3 depicts the share of the gross domestic product and of total federal outlays allocated to the military. It shows that whereas the military consumed up to 70 percent of the federal budget during the Korean War, the Pentagon’s share of the budget has remained below 20 percent since the end of the Cold War. It also shows that whereas the nation devoted more than 10 percent of GDP to military spending during the early part of the Cold War, this share trailed off to less than 4 percent after the Cold War ended.

It is important to be clear about what these figures mean. The declining Pentagon shares indicate not an erosion of military power but rather massive growth in both the federal budget and the overall U.S. economy.7 However, the declining proportion of the economy or the budget spent on the military does point to some important limits on what the American political system was willing to bear absent the impetus provided by an extreme national emergency. These limits required choices that successive postwar presidential administrations made in different ways.

Source: Office of Management and Budget

The Korean War made it possible for the Truman administration to obtain the resources required by NSC 68. Senior officials in the Truman administration attributed greater importance to the security (and the economic recovery) of Western Europe and Japan than did their Republican opponents in Congress. The professional activities of many key administration figures before entering government service—mainly in Wall Street investment banks and law firms—had given them a lively appreciation of U.S. interests in Europe, and a corresponding determination to foster those interests. Men like Secretary of State Dean Acheson believed that security at home required the United States to defend its allies, even at the cost of maintaining large conventional forces overseas. Acheson and others in the Truman administration also expected the spending required to maintain these forces overseas to facilitate the economic recovery of Western Europe and Japan, another major goal of U.S. national security policy.8

The expanded military budgets for fiscal years 1951–53 produced the larger military force these Democrats wanted not only to fight the war in Korea but also to bolster the U.S. garrison in Europe. However, the buildup consumed nearly 15 percent of GDP and created a large budget deficit. For fiscal conservatives, including Truman himself, this was a bitter pill. Two groups within the administration collaborated in urging the president to swallow that pill: internationalists such as Acheson who wanted to expand U.S. military capabilities to meet its new obligations; and advocates of an expansionary fiscal policy, such as Leon Keyserling, who chaired the Council of Economic Advisers, determined to spur domestic economic growth.9 The Truman administration’s support for military spending reflected not only concerns about the Soviet threat but also a specific set of economic priorities. The principal economic concern of postwar Democrats was full employment. By contrast, their Republican counterparts worried more about balanced budgets and inflation. Given its economic implications—and even apart from the military crisis triggered by the Korean War—the Truman administration’s national security policy may well have been one that only a Democratic administration could have adopted.10

This willingness to tolerate the economic consequences of very large military budgets ended when Dwight D. Eisenhower succeeded Truman as president in 1953. The Korean War era military build-up required wage and price controls, government intervention in the market for certain strategic raw materials, and higher taxes. To business leaders and conservatives more generally, these measures were anathema. For sound-dollar, low-tax Republicans, well-represented in the Eisenhower administration by the likes of budget director Joseph Dodge and Treasury Secretary George Humphrey, reining in government spending was imperative, even if it meant cuts in the Pentagon budget. Indeed, in spite of uniformed military predictions of dire consequences for U.S. national security, Humphrey and Dodge persuaded Eisenhower to implement substantial cuts in defense spending.11 As figure 9.2 indicates, defense outlays dropped more than 25 percent between 1953 and 1956, and remained at that level throughout the remainder of the Eisenhower administration.

Beyond their budgetary concerns, many Republicans had been skeptical of the Truman administration’s defense posture with its emphasis on conventional deterrence in Western Europe and Japan. By relying more heavily on strategic forces armed with nuclear weapons, the new administration’s “New Look” promised to reduce military spending enough to bring national security policy into harmony with Republican economic policy priorities. Although Dwight Eisenhower was not among those in his party who viewed the U.S. commitment to Western Europe and Japan as a temporary stopgap, he shared their fiscal preferences and was determined to subordinate the military budget to these concerns. For Eisenhower, the Cold War was as much an economic competition as a military one. He continued to resist proposals to boost defense spending even when the Joint Chiefs of Staff thought such increases were needed.12

The Eisenhower administration offered the first but by no means the last instance of politics constraining postwar defense spending. In effect, the peacetime average depicted in figure 9.1 acted as a baseline to which successive administrations eventually returned. In the 1950s, conservatives concerned about the overall health of the economy returned the budget to this baseline. From the mid-1960s on, pressures to limit military spending came mainly from liberals rather than conservatives, and arguments focused on domestic social programs rather than fiscal responsibility. Caught between the demands of the Vietnam War and his desire to preserve his Great Society, Lyndon Johnson sought to limit or conceal any military increases as long as possible.13 When the Reagan administration aggressively promoted increases in the military budget during the 1980s, it siphoned off a relatively small share of the economy and the federal budget, a fact that almost certainly made the Reagan build-up less politically controversial. Nevertheless, even this build-up had reached its limits well before the end of the Cold War. Although total defense outlays grew through 1989 because of previously budgeted spending, appropriations began to fall in fiscal 1986.14 The budget returned to its usual peacetime baseline and remained there through the 1990s.

The political limits on American military spending affected not only the aggregate size of the defense budget, but also decisions about the allocation of these funds within the Pentagon. Over time, technological advances made weapons not only more effective, but also more expensive. During the several decades of the Cold War, the cost of individual aircraft, tanks, and ships increased by several orders of magnitude. Bomber aircraft offer a good example. Throughout the postwar era, the unit cost of each new generation of aircraft increased by roughly a factor of ten. The venerable B-52, which became operational in the 1950s and continued in service well into the next century, initially cost about $30 million each. The unit cost of the B-1, which entered service in the 1980s, was about $200 million. The B-2s, which began flying the 1990s, cost a staggering $2.1 billion each.15 Unfortunately, although not all weapons systems increased in price at this rate, this pattern is not unusual. Commenting on these increasing unit costs in the 1970s, one Pentagon official wrote (only half jokingly) that the nation would one day be able to afford only “one plane, one tank, one ship.”16 Military personnel also cost more at the end of the Cold War than they did at the beginning. Commerce Department statistics indicate that the real wages of military personnel more than doubled over the postwar era, mainly in an effort to keep pace with rising civilian wages in recruiting an all-volunteer force after 1973.17

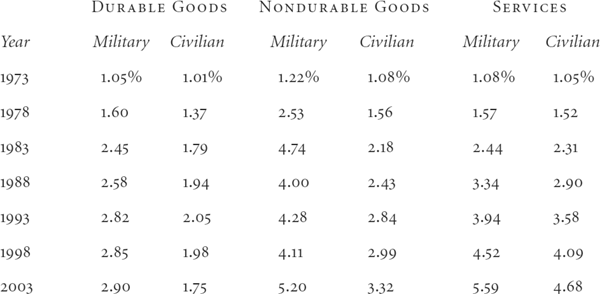

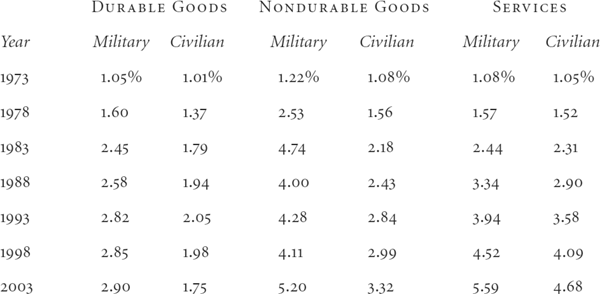

Strictly speaking, not all of these increases constituted inflation. Some of the higher costs bought superior equipment and paid for better-educated personnel. However, genuine price inflation—the cost of buying a roughly identical good or service—was also a serious problem. The price of military goods and services rose more rapidly than did the price of civilian government goods and services and prices in the economy as a whole.18 As table 9.1 indicates, the prices of military services, as well as both durable and nondurable military goods, rose more rapidly than did civilian prices in all these categories. Over the thirty years covered in the table, the differences have been substantial. Military prices for nondurable goods rose 66 percent more than did civilian prices in this category. Durable goods prices rose 57 percent more. The military price of services rose 20 percent more than did the civilian price. In short, elevated rates of price inflation added to the cost of superior technology, making virtually everything the military budget purchased more expensive over time.

The fact that the unit costs of major weapons systems and the wages and benefits of military personnel rose steadily while the budget remained relatively constant had important structural implications. In essence, the emphasis shifted from quantity to quality. Over time the U.S. military came to consist of fewer (but presumably more capable) weapons and personnel. In the 1990s, some observers began to argue that such a force could exploit emerging information technologies to gain a decisive military advantage, but the Pentagon’s force structure was already moving in this direction well before such arguments made a virtue of this necessity.19 For example, the number of navy ships at the peak of the Reagan buildup in fiscal 1987 stood at 594, falling to 337 by fiscal 2001. By comparison, the number of ships never fell below 812 during the budget-conscious Eisenhower administration, or below 523 during the 1970s, another trough in postwar military spending.20 Because the costs associated with military personnel rose more rapidly than almost any other item in the budget, cuts in personnel strength became especially attractive to budget-conscious defense policymakers.21 Increasingly, the Pentagon sought to substitute technology for personnel. Figure 9.4 illustrates this trend, showing dollars spent per man or woman in uniform. This figure rose steadily throughout the Cold War, accelerating after the end of the draft in 1973, and again during the post–Cold War era.

The capital-intensive force structure that has resulted from budgetary pressures has potentially important if uncertain implications for U.S. policy. If information technology is facilitating a “Revolution in Military Affairs,” then the United States enjoyed a substantial head start in taking advantage of this opportunity by the end of the Cold War. On the other hand, whatever the advantages of technological sophistication, a smaller force has its limits. Because even technologically superior forces cannot be in two places at once, small size limits the number of operations that can be conducted simultaneously. Moreover, some missions, such as peacekeeping, occupation, and counterinsurgency, are unavoidably labor-intensive, requiring the presence of large numbers of troops on the ground. If the United States cannot provide these troops, it will have to outsource this function, relying on mercenaries (in contemporary parlance, contractors) or allies to take up the slack. Yet mercenaries are expensive and less than fully reliable. And as the diplomatic wrangling over the war in Iraq suggested in 2002 and 2003, obtaining allied cooperation limits American freedom of action.

Source: Department of Defense

MILITARY SPENDING AND THE AMERICAN ECONOMY

What were the results of high military spending for the American economy? Cold War critics of the Pentagon budget worried that it might hurt overall economic performance, as well as channeling federal resources away from other desirable programs. There are indeed solid grounds for concern about the economic implications of military spending. Nevertheless, in the postwar United States, Pentagon spending did not have large or long-lasting adverse effects on the overall economy or even on the government’s ability to support other priorities.

Economists have suggested two major avenues through which military spending might theoretically affect the economy: by influencing the allocation of resources in the economy as a whole, and through technological “spillovers” from military spending into the civilian economy.22 The impact of defense spending on the allocation of resources within the economy could be either bad or good. When the economy is at or near full employment, diverting resources from civilian to military use will reduce economic growth. Resources used for military purposes, such as tanks or fighter jets, have fewer economic benefits than those employed to produce goods and services in the civilian sector, such as automobiles or airliners. Moreover, military demand for certain materials such as steel, electronic components, and the like, may drive up the prices of these items and contribute to inflation. On the other hand, when substantial unused economic capacity exists, devoting resources to military purposes would not draw them away from other uses. By using labor and capital that would otherwise be unemployed, defense spending could actually promote economic growth. The beginning of World War II demonstrated the positive effects of military spending, helping the United States recover from the Great Depression. The Vietnam War demonstrated the negative effects: because that conflict took place during the relatively prosperous 1960s, when the economy was much closer to full employment, increased military spending helped fuel inflation.

Economic conditions like those prevailing at the beginning of World War II or during the Vietnam era were not the norm. Across the entire postwar era, the impact of military spending through the allocation of resources was generally quite small. As some critics feared, there is evidence that military spending came partly at the expense of civilian investment.23 On the other hand, military spending propped up some sectors of the economy at politically or economically propitious moments.24 On balance, these conflicting dynamics did not add up to any clear effect on overall economic growth.25

The impact of spillovers from military spending into other economic activities has also been modest. Technologies developed for military use sometimes found civilian applications as well. Throughout the postwar era, many innovations in aviation, computers, and electronics—including the global positioning system and the Internet—got their start in military research and development programs. Similarly, many people received education and training in the military that they later put to use in civilian life. Not all the potential spillovers were beneficial, however. In spite of the success of some military technologies in civilian economy, military research was still less likely to produce useful civilian-sector applications than was civilian-sector research during the postwar era. In spite of well-known positive spinoffs like those just mentioned, the broader effects of military research on productivity have been small.26

Apart from its impact on the economy as a whole, many Cold War critics worried that high levels of military spending might force a tradeoff between “guns and butter” in the federal budget. In fact, military spending did not constrain the growth of civilian government spending during the Cold War era.27 In practice, the United States generally incurred budget deficits in order to finance both military spending and social programs at times when the two priorities appeared to conflict. Confronted with an apparent need to choose guns or butter, the Congress typically opted for both, passing the bill on to future generations.

Although the overall pattern is clear, it requires some qualification. Even though there was no general tradeoff, military spending did influence funding for domestic social programs at particular points in time, most notably during the wars in Korea and Vietnam. The buildup associated with NSC 68 and the Korean War prompted the Truman administration to abandon the most ambitious social programs it had proposed, such as its national health insurance plan. Strictly speaking, there was no direct budgetary tradeoff, because nearly all the military spending was financed through borrowing and increased taxes. The cuts in non-defense programs, which amounted to only $550 million in the fiscal 1951 budget, came nowhere close to balancing the massive increase in military outlays, which totaled over $23 billion by the end of the fiscal year. However, the political necessities of rearmament certainly put an end to Harry Truman’s “Fair Deal.”28

The Vietnam War produced a similar result, forcing Lyndon Johnson to scale back his domestic social programs, but once again for political rather than strictly budgetary reasons. Through 1967, Johnson sought to finance both his “Great Society” and the war in Vietnam without higher taxes, an effort that ultimately proved futile. In the fall of 1967, Johnson tried to persuade congress to increase taxes but Wilbur Mills (D-AR), the powerful conservative chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, refused to cooperate. Arguing that “I just do not believe that when we are in a war that is costing us $25 to $30 billion a year we can carry on as usual at home,” Mills demanded cuts in Johnson’s social programs, which he disliked in any case. Johnson held out against Mills until March 1968, when a financial crisis (also exacerbated by the overseas military spending associated with the war in Vietnam) forced him to give in.29 As had been the case during the Korean War, the ensuing cuts in domestic spending did not compensate fully for the expenses associated with Vietnam, but the war’s costs clearly undermined support for Johnson’s domestic programs. Political realities proved more important than economic ones.

By the time the Cold War ended, the possibility that military spending could influence either the economy or overall government spending was becoming increasingly remote. The trends shown in figure 9.3 show why. Because military spending remained fairly constant in real terms while both the economy and the federal budget grew enormously, the economic and budgetary importance of military spending diminished. Even the large boost in military spending that followed the September 11 terrorist attacks, raising the military budget to levels comparable to the peak spending years of the Cold War, consumed less than 20 percent of the federal budget and less than 4 percent of gross domestic product, shares lower than those seen at any time since 1950. These facts help to explain why critics of the Bush administration’s foreign and defense policies said relatively little about the size of the military budget. The major national debates about the need to choose “guns or butter” may well be a thing of the past. Future disagreements over national security policy are more likely to focus on issues where there is genuine scarcity. For example, while the supply of budgetary dollars is abundant, the supply of people is not. Recent military recruiting difficulties suggest that the limited number of citizens willing to volunteer for military service may constrain American policy in important ways. The potential solutions to a personnel shortage, ranging from a return to the draft to the acceptance of limits on overseas commitments, are all likely to spark controversy.

DISTRIBUTIVE IMPLICATIONS

Critics of postwar military spending worried a lot about its economic effects, but they were even more concerned about its political implications. During the early Cold War era, conservatives like Senator Taft and President Eisenhower feared that the United States might become a “garrison state.”30 Increased military spending entailed higher taxes, expanded bureaucracy, and a general growth in the power of the state, all of which seemed to threaten free enterprise and eventually to endanger democratic government.31 Subsequently, liberal critics worried about the growth of militarism and a “military-industrial complex” that would undermine democratic control of foreign policy and promote war.32 In both cases, the critics worried that constituencies benefiting most from military spending would sacrifice core political values in their quest for power and profit. Postwar military spending did not destroy American democracy or the free enterprise system, but it did have important political consequences. The changing identity of the domestic “winners” and “losers” from military spending tells a politically important story. Not surprisingly, the impact of military spending on different regions and socioeconomic classes helped shape the politics of national security policy.

Cold War military spending had major consequences for the regional distribution of manufacturing industries in the United States, contributing to the spread of these industries out of the Northeastern quadrant of the country and into the South and West. In 1939, the fourteen states from Illinois east and from Pennsylvania north produced 71.1 percent of the country’s manufacturing output, and contained 68.8 percent of its manufacturing jobs.33 By 2001, the Northeast’s share of national manufacturing output and employment had fallen to 39.7 and 40.2 percent, respectively.34 Military spending was certainly not the only reason for this shift, but it was nevertheless an important contributing factor.35

The impact of military spending on the regional distribution of manufacturing began with the massive mobilization of the economy for World War II. Although the Northeast received the largest share of government contracts during World War II, new production facilities were set up outside established manufacturing centers. The need to supply the war in the Pacific, along with regulations prohibiting the construction of munitions plants within 200 miles of the coast, prompted the building of new facilities in areas that had previously had little manufacturing employment, such as Dallas and Oklahoma City. Labor shortages in traditional manufacturing centers also encouraged this practice: it was cheaper and easier to establish new plants in areas where labor was relatively abundant than to import workers from other parts of the country.

The legacy of the World War II mobilization proved important in two respects. First, the existence of manufacturing facilities in the South and West created expectations that these regions ought to receive a share of government contracts during the Cold War. Second, military investment in the South and West during World War II had emphasized the aircraft manufacturing and petroleum industries. During the postwar era, these industries grew especially rapidly, giving an important if unforeseen spur to the growth of manufacturing outside the Northeast.36

The contribution of military spending to the growth of manufacturing industry in the South and West also reflected partisan differences over the allocation of the military budget as well as the exigencies of the wars in Korea and Vietnam. The party differences that had developed during Truman and Eisenhower administrations persisted throughout the Cold War. The Democrats favored spending for conventional forces, although that commitment declined over time, and disappeared altogether under the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Republican administrations from Eisenhower through the younger Bush tended to favor strategic forces and to emphasize strategies that relied more heavily on technological advances. These preferences turned out to have important implications for the regional distribution of military spending, as well as for the content of the arsenal.37

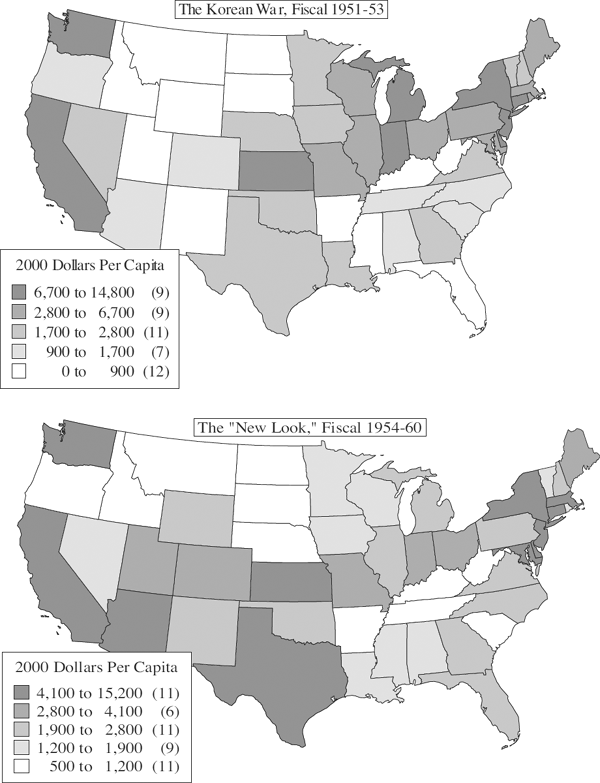

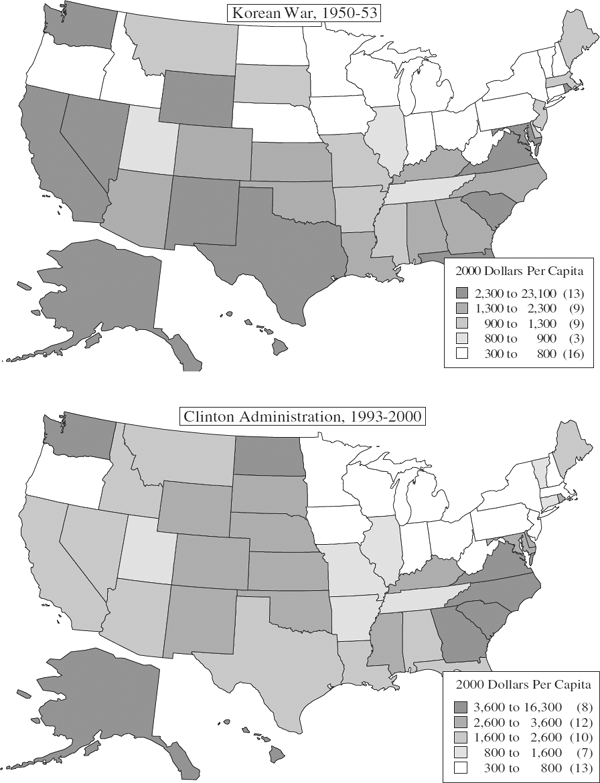

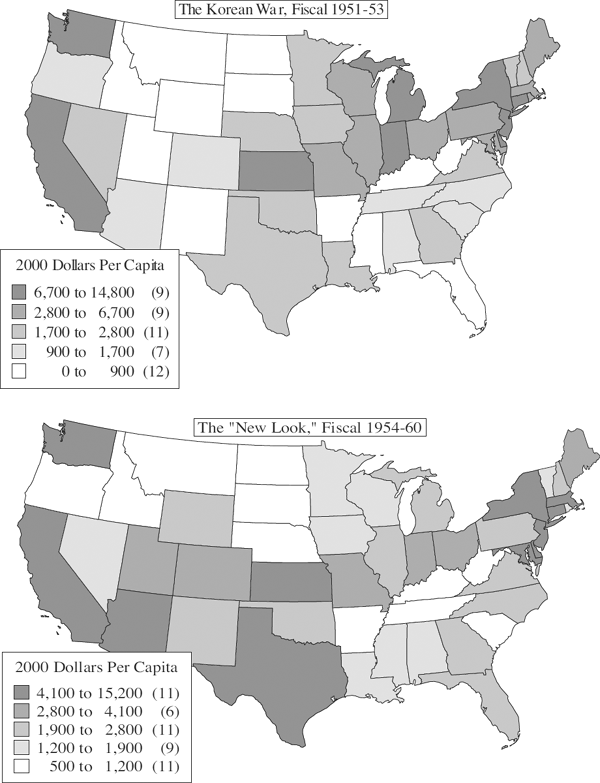

The build-up that followed NSC 68 and the Korean War reflected the Democratic preference for conventional forces, a strategy that favored the predominantly Democratic states of the Northeastern manufacturing belt. The upper panel in figure 9.5 indicates the total per capita value of prime contracts issued by the Department of Defense during the three highest-spending fiscal years of the Korean War.38 Although several states outside the Northeast, especially aircraft manufacturing centers like California, Washington, and Kansas, received substantial benefits from these prime contracts, the Northeast received the lion’s share. This regional concentration also reflects the fact that it was easier to convert factories from military to civilian use during the Korean War than it would be later. At the time, conventional war consumed huge quantities of manufactured goods that were similar to those produced for civilian use.39 (As military hardware grew more technologically advanced in later years, the resemblance between military and civilian products diminished.) The Northeast, where most civilian manufacturing in the United States took place, was in the best position to meet these needs.

The Republicans who took office in 1953 had a different strategic vision and different spending priorities. As the lower panel in figure 9.5 indicates, Eisenhower’s New Look geographically dispersed military spending across a wider range of states, and shifted it away from traditional manufacturing centers. The end of the Korean War and Eisenhower’s more stringent fiscal policies greatly reduced military procurement, with the total value of prime contracts falling from an annual average of $176 billion in 2000 dollars during the Korean War to $87 billion between fiscal 1954 and 1960. Because of the reduced emphasis on conventional forces, the impact of this 51 percent decline in contracting fell most heavily on Northeastern manufacturing. Although New York and New England continued to receive a substantial per capita share of prime contracts, the Midwestern manufacturing belt suffered huge losses. States in the East North Central census region (Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois) lost an average of 82 percent of the value of their prime contracts. The declining military demand for motor vehicles made Michigan the biggest loser in the entire nation, with firms in the state losing 92 percent of the value of prime contracts they had received during the Korean War. By contrast, many states in the Rocky Mountain and Great Plains regions actually gained during the New Look, in spite of the overall drop in military spending. (The net winners were Florida, South Dakota, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and North Dakota.) These states had produced fewer of the conventional manufactures most heavily cut after the end of the Korean War, and more of the relatively exotic high-technology items the New Look demanded.

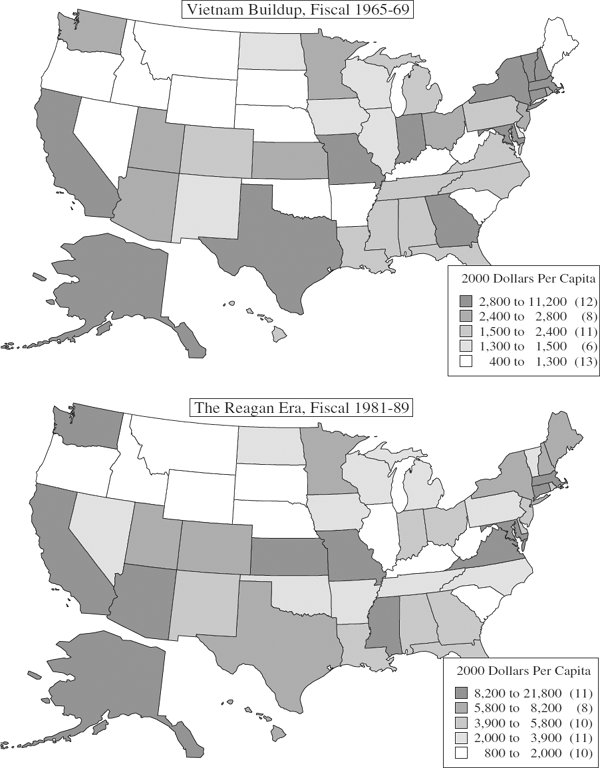

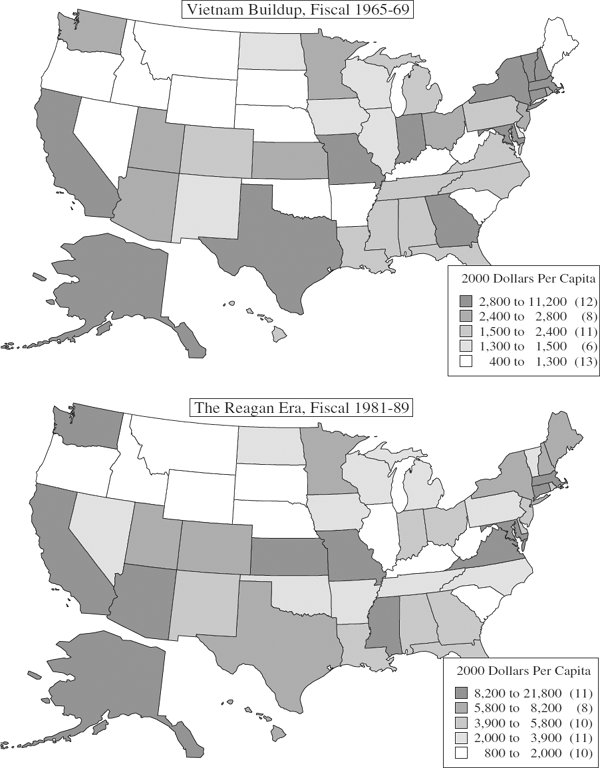

The onset of the war in Vietnam once again required large quantities of materiel that could be produced by converted civilian industries. That meant more defense business for firms in the manufacturing belt. However, important differences between the Korea- and Vietnam-era buildups limited the flow of benefits to the Northeast during the Vietnam War. First, unlike the Truman administration, the Johnson administration did not couple its war effort with plans for maintaining a substantially larger military force after the war ended, and did not convert civilian industries to large-scale military production. Although the Johnson administration’s efforts to contain the cost of the war were not successful, the Vietnam-era buildup in military procurement was still smaller than that associated with NSC 68 and Korea, lasting only from the 1966 through 1969 fiscal years. During this period, the value of prime contracts rose to $144 billion in 2000 dollars, a 66 percent increase over the New Look period, but smaller than the $176 billion annual average during the Korean War.

Second, in part because military industry had shifted away from the Northeast during the New Look, military contracting was also less geographically concentrated in the Northeast during the Vietnam War than it had been during the Korean War. This fact is evident in the upper panel of figure 9.6. Of the five East North Central states mentioned earlier, only Indiana and Wisconsin gained more than the national average in the value of prime contracts. Michigan gained 46 percent, but still received only $408 per capita in prime contracts during the Vietnam-era buildup compared to the $3,470 per capita firms in the state had received during the Korean War. The biggest geographic beneficiaries of Vietnam-era prime contracts compared to the New Look were located in the South. In Texas, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee, for example, the annual average value of prime contracts all more than doubled. American manufacturing was still concentrated in the Northeast during the 1960s, but most of it continued producing civilian goods during the war. The benefits of Vietnam-era military contracts went mainly to defense contractors in other parts of the country.

The Reagan administration’s military buildup differed from those associated with the wars in Korea and Vietnam in ways that further benefited the South and West rather than the Northeast. Because this buildup was not associated with a major war, it emphasized procurement rather than operations and maintenance. It was also sustained for a longer period of time than the Korean War or Vietnam War buildups, lasting from the 1981 through 1989 fiscal years before trailing off at the end of the Cold War. During this period, the value of prime contracts averaged $174 billion annually, roughly the same as during the Korean War. The Reagan administration’s spending priorities resembled those of the Eisenhower administration, with its stress on strategic forces and advanced technology, more than those of the Democrats who had presided over the preceding military buildups.

A comparison between the regional beneficiaries of the 1951–53 and 1981–89 military buildups, shown in figures 9.5 and 9.6 respectively, reveals much about the evolution of military spending during the Cold War. Leaders in aerospace like California, Washington, and Kansas still received relatively large per capita shares of prime contracts in both periods, but states in the old manufacturing belt received less during the 1980s in both absolute and relative terms. Of the fourteen New England, Mid-Atlantic, and East North Central states that had once dominated manufacturing and military industry in the United States, all but Massachusetts received a smaller annual per capita level of military prime contracts during the Reagan buildup than during the Korean War. In percentage terms, seven of the ten biggest losers were located in this region. As was the case during the New Look, Michigan was the biggest loser, suffering a 91 percent decline, almost exactly what it had experienced in the transition from the Korean War to the New Look.

The pattern of Democratic procurement favoring large conventional forces and Republican procurement favoring high-tech strategic forces ended with the Clinton administration in the 1990s. The Clinton administration abandoned the old Democratic commitment to a large conventional force, opting instead to continue Republican-style reliance on better technology and fewer personnel. This decision was a concession to new fiscal and technological realities. By the 1990s, standards for the technological sophistication of military equipment and the pay of military personnel were greater than ever, and the associated costs were much higher. Barring a return to a technologically simpler force—something no one contemplated—building a large conventional force in the 1990s would have been exceedingly expensive. Few in the Democratic Party were still willing to pay such a price.

In adopting Reagan-era spending priorities, the Clinton administration did not redirect military procurement back toward the “rustbelt.” Instead, the “gunbelt” states that had received the largest share of prime contracts during the Reagan buildup continued to do so under the Clinton administration.40 Of the ten states enjoying the greatest per capita success winning military contracts under the Reagan administration, eight remained in the Clinton-era top ten. Clinton made no effort to reverse the trend toward a more capital-intensive military, which accelerated during his last three years in office. The personnel strength of the force also fell by 18 percent between fiscal 1993 and 2001. As the shift toward a more technology-intensive force continued, firms in the Northeast continued to lose ground in prime contracting to firms in the South and West.

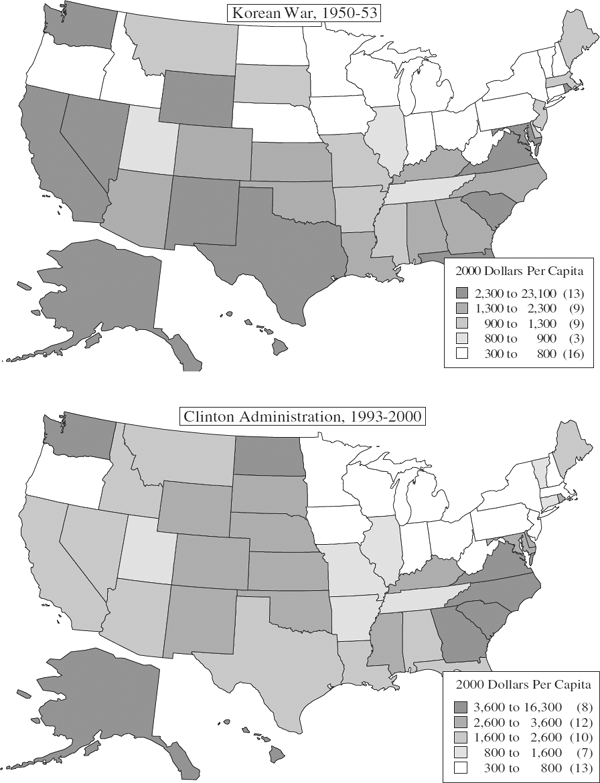

Defense contracting is not the only way military spending influenced the regional economies. Data on personal income from military sources gathered by the Department of Commerce offer a useful complement to the prime contracting data. These data reflect mainly military wages and salaries as well as some activities associated with military bases. They show an even more pronounced pattern favoring the South and West. The two maps in figure 9.7 depict the share of personal income derived from military spending in each state during the Korean War and the Clinton administration. As the maps suggest, throughout the postwar era military spending accounted for a higher share of personal income in the South and West than it did in the Northeast. The fact that these regions always hosted more military bases than did the Northeast suggests that spending associated with these facilities canceled out much of the Northeast′s advantage in prime contracting during the wars in Korea and Vietnam. The bottom line is that military spending since World War II redistributed income from the Northeast to the South and West. The regional disparities in income from military bases and salaries were clear throughout the postwar era, and amplified disparities in military contracting that grew over time.

As the regional beneficiaries of military spending became increasingly Southern and Western over time, they also became wealthier. Once again, a comparison of the major military build-ups of the Cold War era is instructive. Fighting wars in Korea and Vietnam required greater spending on operations and maintenance and on personnel. These types of expenditures tend to reduce poverty.41 Much of this effect is due to the educational spinoffs from this type of spending. The relatively poor benefit more from military training and education than do the relatively wealthy because the poor have less education to begin with. Moreover, drafting relatively large numbers of people, especially from low-income groups, lowers unemployment by reducing the number of people looking for jobs.42 Neither of these effects should generate enthusiasm for war as an anti-poverty program, but they are nevertheless quite real and relevant to understanding the impact of military spending during the first part of the Cold War.

Because it was not associated with a war, and reflected a different set of spending priorities than did earlier military buildups, Reagan-era spending lacked the poverty-reducing side effects of these earlier increases in the military budget. Indeed, increased peacetime military spending is correlated with increased poverty and inequality. Such a relationship is not surprising in view of the character of defense outlays during the 1980s. In spite of higher military spending, the number of men and women in uniform did not increase during the 1980s, limiting the education and training spillovers that have tended to help low-income groups. Moreover, the tightening of educational standards required of new recruits—in practical terms making most high school dropouts ineligible for military service—may also have had the unintended consequence of reducing these spillover effects. As military procurement focused on more specialized and exotic systems, and less on goods similar to those produced by civilian industry, the workforce in defense industries also became wealthier and better educated. Overall, the increasingly capital-intensive force the United States has established since the 1980s has fewer ancillary social benefits than did the early Cold War era force.43

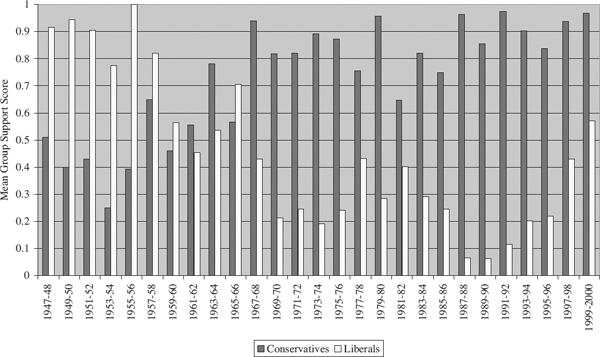

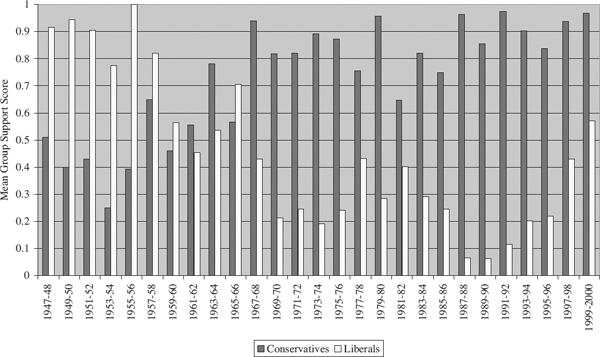

How did the changing identity of the winners and losers from military spending affect politics? There is little evidence to support the proposition that members of congress voted for military spending bills strictly based on whether their constituents stood to gain as a result.44 Nevertheless, there is evidence to suggest that conservative or liberal support for military spending warmed or cooled depending on which constituencies benefited most from it. During the early Cold War era, congressional liberals tended to support military spending and conservatives to oppose it. By the early 1960s, these two factions had begun to switch their positions, a transformation that was complete by the early 1970s, and persisted through the rest of the Cold War. Figure 9.8 illustrates these trends, showing the proportion of votes in support of maintaining or increasing military spending cast by the most liberal and most conservative senators. The shift in both groups’ behavior makes sense in terms of the changing distributive implications of military spending.

Liberals were associated with the interests of organized labor and the urban Northeast. Indeed, one scholar has described liberals as “the northern industrial wing of the Democratic party.”45 As we have seen, military spending during the early Cold War era tended to favor the interests of the industrial northeast. At the beginning of the Cold War, when manufacturing industries in the Northeast received the greatest share of prime contract from the Department of Defense, Northeastern congressional delegations were more likely than those from other regions to support military spending. Delegations from areas of the country that received a smaller share of the benefits were less so. By the 1970s, this situation had been reversed, with more conservative delegations from the South and West compiling more reliably pro-military voting records. The political complexion of the Northeastern congressional delegation remained relatively liberal, but that no longer implied enthusiastic support for military expenditures.46

Beyond the regional dynamics, the conservative shift from opposition to support for military spending also makes sense in terms of its changing economic implications. The relatively large share of the economy spent on the military during the early Cold War era required high taxes or large budget deficits, posed a serious risk of inflation, and often included substantial government intervention in the economy, all of which were anathema to conservatives, particularly those from Mountain states and areas of the Midwest outside the manufacturing belt.47 Over time, however, the distributive implications of military spending became less of a barrier to conservative support. As defense outlays declined in terms of gross domestic product and the federal budget, their implications for taxes and inflation diminished.

Of course, the distributive implications of military spending do not entirely account for the politics of this issue. For one thing, liberals and conservatives also argued about the foreign policy objectives military spending supported, and these considerations probably had a greater effect on the positions they adopted than did the parochial benefits of defense outlays.48 Neither the regional origins nor ideological orientation of members of congress or of other political actors fully explain all the positions they adopted. Nevertheless, despite many exceptions to the patterns discussed here, the changing identity of the economic winners and losers from military spending had important political implications.

CONCLUSION

Where has more than fifty years of elevated military spending left the United States? The evidence reviewed here suggests three major conclusions about postwar spending, each of which has important implications for the future of U.S. national security policy. First, military spending has not contributed to the decline of the United States as a world power by undermining its economy. Military expenditures have remained fairly consistent in real terms since 1950, but have consumed a steadily declining share of both the American economy and the federal budget. In contrast to the plight of the Soviet Union, which had a smaller economy and did not enjoy continuing economic growth, the United States saw the burden of fighting the Cold War ease the longer the struggle lasted. Since the end of the Cold War, the defense burden has become lighter still. The military spending increases that followed the September 11 terrorist attacks were as large as any undertaken during the Cold War, but consumed less than 4 percent of GDP and less than 20 percent of the federal budget. Both these figures are lower than those that prevailed at any point during the Cold War.

The adverse economic consequences of military spending have not been nearly so dire as critics feared during the early Cold War era. The effects of military spending on economic growth during the Cold War were mixed and generally small. Similarly, there was no systematic trade-off between military and civilian spending in the federal budget, although the political implications of elevated military spending influenced funding for civilian programs at certain times, particularly during the Korean and Vietnam Wars. All the economic effects of military spending diminished as the military share of the economy and the federal budget declined. There may be many reasons for questioning contemporary U.S. national security policies, but the fiscal and economic consequences of military spending are not among them.

The absence of economic constraints on American military power is worth emphasizing both because it is historically unusual and because it has critical implications for the future of American foreign policy. Major powers have often been exhausted by their efforts to retain their position in the international system.49 In view of the longstanding American effort to build and maintain a world order congenial to its economic and security interests—the “healthy international community” mentioned in the opening quotation from NSC 68—it is not surprising that the United States chose to maintain a relatively large military force after the end of the Cold War. What is surprising is that the United States has been able to maintain this force at such a low cost. The Cold War, in spite of the huge absolute expenditures it entailed, left the United States in a position to retain—and even to expand—its military advantage over all other states without seriously damaging its own economy. As the war in Iraq suggests, American military supremacy does not mean the nation can quickly defeat all possible opponents, but it does mean that other major powers will find it very difficult to seriously threaten the United States. This unprecedented situation is the cornerstone of American national security policy, and it has profound implications for other states as well. It may be the single most important fact about the contemporary international system.

Second, the economic implications of postwar military spending for different regions and groups within the country are more important than its effects on the economy as a whole. Pentagon expenditures benefited the South and West at the expense of the Northeast, particularly the Great Lakes manufacturing belt, and contributed to the geographic shift in manufacturing out of the Northeast. The Northeast consistently received a smaller share of the economic benefits of military bases, and wages and salaries.

The distributional effects of military spending were both a cause and a consequence of political divisions over national security policy. The Truman administration’s preference for conventional forces in order to bolster the security of U.S. allies in Western Europe and Japan, as well as the need to fight the Korean War, tended to benefit the Northeast. The Eisenhower administration’s search for a less costly alternative strategy resulted in an emphasis on strategic forces and nuclear weapons. It also tended to benefit the West and South. In both cases, the political constituencies these administrations represented set important limits on their strategic choices and corresponding decisions about the allocation of military spending. In this sense, politics drove spending decisions and determined their distributive consequences.

On the other hand, changing priorities in military spending also produced long-term (and probably unforeseen) changes in patterns of political support for it. Liberal support for defense outlays waned as the benefits of these outlays for heavily unionized industries in the Northeast and their poverty-reducing side effects diminished. At the same time, conservative support for military spending grew as its consequences for taxes, regulation, and government spending changed. The identity of the domestic winners and losers from military spending do not fully explain these political changes, but they were an important source of support and opposition to Cold War national security policy.

The distributive implications of military spending underscore the inescapably political nature of these policy choices. Even if all Americans could agree on national security policy goals in principle, the spending required to achieve these goals would still create domestic winners and losers. Although military spending is no longer as economically important as it was when it consumed ten or fifteen percent of GDP, it is still substantial enough to engender political conflict.

In view of the political character of military spending, the third conclusion follows from the second. Political considerations rather than economic realities have dictated the upper limit on what the United States has been willing to pay for defense. Even though the burden of defense fell steadily from the 1950s onward, the United States only episodically increased the absolute level of resources it allocated to the military. After each major buildup of the postwar era, military spending consistently reverted to a level very near its postwar peacetime average. This pattern continued even during the 1980s and 1990s, when military spending consumed a relatively small share of both the budget and the economy as a whole. The military budget was headed downward well before the fall of the Berlin Wall or the collapse of the Soviet Union, and it remained at typical postwar peacetime levels throughout the 1990s.

The political limits on military spending have important consequences for the future of American national security policy. The fairly consistent level of postwar spending did not buy the same military force across the entire period. In part because of the rising unit costs of high technology military equipment, the United States purchased a progressively smaller number of these (presumably) superior weapons systems and paired them with a declining number of relatively better-paid personnel. The United States military relied increasingly on technology as a substitute for personnel over the course of the Cold War, especially during its final decade. The budgets of the first fifteen years after the end of the Cold War give no indication that any change in this pattern is imminent.50 The future of American power depends on part on whether this force is as effective for the missions assigned it in the future as it was in deterring the Soviet Union. Current events provide ample reasons for doubt. The irony of American military supremacy is that it makes the nation more likely to find itself involved in the unconventional wars for which its capital-intensive military force is least well-suited. Other states are unlikely to challenge the United States with conventional military forces, but guerrilla forces like those fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan are not so easy to deter. These conflicts suggest that technological superiority is not always a good substitute for more “boots on the ground,” and that guerrilla forces can still do substantial damage to a technologically superior force. Finding a solution for this problem, whether it means restructuring American military forces or limiting the range of conflicts in which they are deployed, poses a major challenge for American policymakers.

Notes