Buoyed by the publication of The Pothunters, Wodehouse was discussing a new contract with his publishers.

TO MESSRS. A. & C. BLACK

23 Walpole St.

S.W.

December 8. 1902

Dear Sir.

In reply to your letter of today, I beg to acknowledge receipt of your cheque for £6.18.7. I must thank you for your very liberal proposal with regard to my next book, and I shall be only too glad to avail myself of it. I have finished a public school story of almost exactly the same length as The Pothunters, and can forward it immediately if you wish it. The title of the book is The Bishop’s Uncle and like The Pothunters it deals chiefly with the outdoor life of the public school.1 There is a great deal of cricket in the book, in fact, strictly speaking, it is nearly all cricket, for very little else except that game goes on in the Summer Term at school. This being the case, it occurs to me that the book might do better if brought out in the Summer, though of course my knowledge of the science of publishing is very slight. At any rate I will wait until I hear from you before forwarding it. I should very much like Mr R. N. Pocock to illustrate it, if you have no objection. We worked together for so long on the Public School Magazine that we both see things from the same point of view as regards public school matters. I hope, if you do not like The Bishop’s Uncle at first sight, that you will let me revise it. I can generally improve on my work at a second attempt. I am doing a good deal of work for Punch now, and the editor sends back two out of every three of my MSS to be altered, and he always takes them when I return them in their corrected form.

I should be very glad to receive 10% on the Cheap American edition of The Pothunters.

Yrs. faithfully

P. G. Wodehouse.

1 This was to be retitled The Prefect’s Uncle (1903).

Throughout his early career, Wodehouse’s friendship with Townend and Herbert Wotton Westbrook was vital. There was, however, always a competitive edge between Westbrook and Wodehouse, especially over ideas for stories. One night, in Westbrook’s Rupert Street digs, Townend told the story of one of his old acquaintances, Carrington Craxton, a man who ‘drank too much’ and ‘sponged, more or less on people’, and tried to start a chicken farm. Both Wodehouse and Westbrook saw potential in the sketch, and each wished to develop it into a novel.

TO WILLIAM TOWNEND

22 Walpole Street,

S.W.1

March 3. 1905

Dear Willyum,

This is great about our Westy. Damn his eyes. What gory right has he got to the story any more than me? Tell him so with my love. As for me, a regiment of Westbrooks, each slacker than the last, won’t stop me. I have the thing mapped out into chapters, & shall go at it steadily. At present it isn’t coming out quite so funny as I want. Chapter One is good, but as far as I have done of Chapter Two, introducing Ukridge, doesn’t satisfy me. It is flat. I hope, however, to amend this.

[…]

Do send along more Craxton stories (not improper ones).2 I am going to pad book out with them, making Ukridge an anecdotal sort of man. If they are mildly improper, it’s all right. Do come up on 10th. You needn’t bring Westy though. I am very much fed up with him just now, as he has been promising all sorts of things in my name without my knowledge to some damned cousins of his, the Goulds, which might have made a lot of worry for me. I say, I boxed 2 rounds with Brougham in the Junior Study tonight, & he put it all over me. In the second round he was giving me particular Hell. I believe that he might do something if he got down to 10 st. & went up.3

R.S.V.P. I have locked up your MS in case of a raid by Westy. Don’t give him all the information you’ve given me. Not that he would ever get beyond chapter 2, though. His intention of rushing through his book doesn’t worry me much!

Yours

PGW

1 PGW’s London digs from 1902 to 1904. He uses this address (changed by one number) in Not George Washington: ‘A fairly large bed-sitting room was vacant at No. 23. I took it, and settled down seriously to make my writing pay’ (Chapter 3).

2 Many years later, Townend described the Craxton of 1902: ‘he was the worst football player that ever lived […] he played in a sweater, old-fashioned knickerbockers […] brown stockings. […] And his pince-nez really were secured by ginger-beer wire. […] He could not keep his feet, he could not run […] and the boys on the touch line were convulsed’, William Townend to PGW, 22 March 1957 (Dulwich).

3 Wodehouse kept up his boxing with the boys at Emsworth House School.

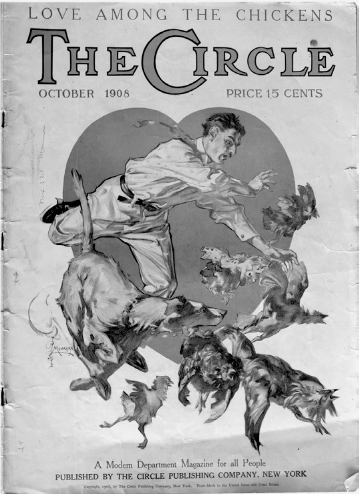

The novel was to become Love Among the Chickens. While Craxton provided the inspiration for Ukridge (the hero of the novel, famous for his chaotic money-making schemes and equally careless wardrobe), his character was fleshed out by Wodehouse’s perceptions of Westbrook himself. Once the novel was completed, Wodehouse realised that he needed an agent, and a sharper focus on placing and marketing his work.

TO J. B. PINKER

‘By the Way’ Room

Offices of ‘The Globe’

367 Strand

W.C.

January 16. 1906

Dear Sir.

I rang you up on the telephone today to ask if you would handle my work. I have made a sort of corner in public-school stories, and I can always get them taken either by the Windsor or one of the Pearson magazines or the Captain.1 I get about £2.10 a thousand words for them, but I fancy that judicious management could extract more.2 I should be very glad if you could find time to place them for me.

I have also written a novel of about 70,000 words.3 I have had this typed once, and a friend of mine on the New York World is handling the typed copy in America. Would it be necessary to have this M.S. re-typed for England? The copy I have by me is perfectly clearly written.

Yours faithfully

P. G. Wodehouse

1 The Windsor Magazine, ‘an Illustrated Monthly for Men and Women’ (1895–1939), featuring writers such as Arnold Bennett, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling and Jack London. The Captain, a Magazine for Boys and ‘Old Boys’ (1899–1924) aimed at the public school market, and those who sought to identify with them, with the emphasis on Muscular Christianity, Imperialism and good sportsmanship.

2 £2.10 – about £175 by today’s standards.

3 Love Among the Chickens (1909); published in the USA as a serial in 1908–9.

TO J. B. PINKER

Offices of ‘The Globe’

367 Strand

W.C.

May 4. 1906

Dear Mr Pinker.

I think the best thing would be to take the £2.2 & then sell the story elsewhere later on, as he suggests. After all, there’s not much difference between £2.2 & £3.3, and when I am a great man we will sell ‘Signs and Portents’ for much gold.1

You might try & make him raise it to £2.10; but failing that take the £2.2. Have Pearson’s taken ‘The Renegade’? I heard from Everett that they were reading it.2 By the way, I have a school story, The White Feather, strong plot, scintillating humour, length 50,000 words, just finished as serial in The Captain. Couldn’t you sound a few publishers about it before sending it round? Sort of accept tenders for it. Or can this only be done with men like Doyle & Kipling?3

Yours sincerely

P. G. Wodehouse

1 PGW’s ‘Signs and Portents: A Cricket Story’, published in Stage and Sport on 19 May 1906.

2 Wodehouse’s story ‘The Renegade’ was not taken by Pearson’s and has not survived.

3 The White Feather, the tale of a schoolboy’s redemption from cowardice through boxing prowess, was published in the UK by A. & C. Black in 1907.

In 1906–7, Wodehouse and Westbrook collaborated on the novel Not George Washington. Despite this, their difficult friendship continued. ‘Brook’ is ‘a complete shit’, Wodehouse confided to Townend. As the following letter shows, Wodehouse was scrupulous in observing the boundaries of intellectual property. Westbrook took a more relaxed approach to questions of ownership, helping himself to various items belonging to Wodehouse and inviting unwelcome house guests to the ‘various houses’ that they shared in Emsworth.

It was during this period that Wodehouse developed one of his most memorable characters – the immaculately dressed, monocle-wearing Rupert Eustace Psmith. Psmith was ‘a kind of supercharged, upper-class version of the “masher” or “knut” of the Edwardian comic paper’. Wodehouse elaborated this classic figure by adding characteristics of the flamboyant Edwardian theatre impresario Rupert D’Oyly Carte. Wodehouse introduced Psmith in his 1908 serial The Lost Lambs, which was eventually to become the second part of his novel Mike.

TO CASSELL & CO., LONDON

The Globe,

367, Strand. W.

August 3. 1907

Dear Sir,

The fact that the preliminary notices of Not George Washington have gone out with the names wrong is a pity: but all the same I must make a point of having them altered. To say that the book is by P. G. Wodehouse and H. Westbrook is absolutely out of question [sic] unless you care to insert the enclosed preface.1 If you do, then let the order of the names stand. If not, they must be altered. I absolutely refuse to give people the impression that I wrote the book with some slight help from Mr. Westbrook when my share in it is really so small.

Will you also please insert the enclosed dedication.

Yours faithfully,

P. G. Wodehouse

1 PGW’s suggested correction read ‘The order in which the authors names are placed on the title page of this book is wrong, and is due to a mistake. The central idea, the working out of the plot and everything that is any good at all in the book are by “H. Westbrook”. The rest is by “P. G. Wodehouse”.’ In the end, this prefatory note was not necessary as Westbrook’s name was placed first.

Not George Washington was dedicated to Ella King-Hall, the sister of the owner of Emsworth House School. Although Ella was sixteen years older than Wodehouse, he was, according to the King-Hall family, ‘half in love’ with her. Ella was a talented writer and musician, and the pair collaborated on a musical sketch, The Bandit’s Daughter, which survived only a few nights of its London run in Camden Town.

TO WILLIAM TOWNEND

Constitutional Club,

Northumberland Avenue,

W.C.1

[1908]

Dear Bill.

It’s all right. Got a plot, thanks. Not much good, but will do. May have to call on you for one or two isolated episodes, possibly, if you can manage, but think I’m all right.

[…]

Go over to Emsworth & see the extraordinary deadbeat old Brook has brought to Tresco.2 Old College tutor of his, absolutely on rocks, has been sleeping on Blackfriars Bridge. Drink, etc. Sort of Craxton, only awful bore. Well worth a visit of inspection, though. It will make you laugh to see Brook & him slouching off to the pub together, each looking seedier than the other. Mind you go.

Send stuff here this week, as shall be in London probably till the deadbeat gets out of Tresco.

Yrs,

PGW

1 The Constitutional Club, PGW’s London address, became the model for the Senior Conservative Club in his Blandings novels, ‘celebrated for the steadfastness of its political views, the excellence of its cuisine, and the Gorgonzolaesque marble of its main staircase’ (Psmith in the City).

2 Tresco, the name of PGW’s country ‘residence’ in Emsworth, which he shared with Westbrook. He subsequently rented and then bought Threepwood, a villa next to Emsworth School. Threepwood was to be immortalised in PGW’s choice of names for his characters in his Blandings Castle stories – the Threepwood dynasty includes Galahad, as well as Clarence, Lord Emsworth.

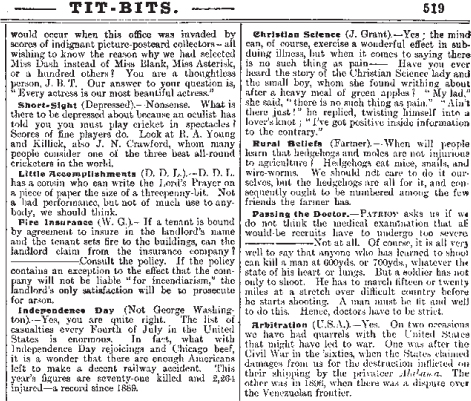

One of Wodehouse’s many collaborative sidelines included freelancing for Tit-Bits – a mass-circulation weekly, which included stories and human-interest features. The most popular page was the ‘Answers to Correspondents’ – an early Edwardian agony column – which Wodehouse handled with his friend Bill Townend. Such pages had been common in the Victorian penny journals. The novelist Wilkie Collins considered these pages both fascinating and highly comic. ‘There is no earthly subject that it is possible to discuss, no private affair that it is possible to conceive, which the amazing Unknown Public will not confide to the Editor in the form of a question, and which the editor will not set himself seriously and resolutely to answer. Hidden under cover of initials, or Christian names, or conventional signatures, such as Subscriber, Constant Reader, and so forth, the editor’s correspondents seem, many of them, to judge by the published answers to their questions, utterly impervious to the senses of ridicule or shame. Young girls beset by perplexities which are usually supposed to be reserved for a mother’s or an elder sister’s ear only, consult the editor. Married women who have committed little frailties, consult the editor. Male jilts in deadly fear of actions for breach of promise of marriage, consult the editor. Ladies whose complexions are on the wane, and who wish to know the best artificial means of restoring them, consult the editor’. The actual editor, George Newnes, had a different view. He saw the page as the most important in the paper. It was his way of keeping in touch with his public – and it was crucial to him that the queries from his readers were sympathetically handled. Wodehouse, like Collins, took the page less seriously, including fictional correspondents along with the actual, and publicising his own works. It was not long before Wodehouse was dismissed from this particular job. Newnes decided to keep such work ‘in house’.

TO VARIOUS CORRESPONDENTS

George Newnes Limited

Editorial Department

Tit-Bits

8, 9, 10 & 11 Southampton Street

Strand

London

August 29. 1908

A Lover’s Trials. – CITIZEN’S grievance is against aunts. Not his own aunts, but those of his fiancée. They insist on accompanying him and the young lady, apparently thinking they are doing the latter a kindness. —— CITIZEN has our sympathy. A little personal reminiscence may interest him. A short time ago we dragged our tired limbs to the Franco-British Exhibition, and there treated ourselves to a trip on the Spiral Railway. As the car reached the top, a young lady, hitherto silent, gave out the following remark to her companion: ‘Well, Henry’, she said, ‘thank goodness, we’ve managed to lose the auntie at last.’ Does CITIZEN see the point?

Wilkie Bard (Druriolanus). – Yes, your friend was right. Wilkie Bard will be the principal comedian in the next Drury Lane pantomime.1

Queer Quarrels (Albert). – Of all disputes this is the silliest. ALBERT loves a red tie. He says it suits his complexion. His wife hates the colour, and wants him to wear purple. She says it is so much more gentlemanly. —— Why not compromise? Would not a tie of alternate purple and red stripes solve the problem? It would be chic and je ne sais quoi (not to mention verb. sap.) without being ostentatious.2 Besides, anything for a quiet life.

American Policemen (U.S.A.). – American policemen have different methods from London policemen, but it must be remembered that they have a different public to handle. The London constable takes it for granted that a word from him will be sufficient, and he is generally right. The American policeman finds it safer to rely on a stout arm and a stouter truncheon.3

Top-Hats (Well-Dressed, Kensington). – Our chief objection to the top-hat is its discomfort. Not that we think it is altogether a thing of beauty.4 But, of course, it does lend a certain air of respectability.

1 Wilkie Bard (1874–1944), pantomime dame and British music hall artist, specialising in ‘coster songs’ and tongue-twisters. Bard did indeed make his reputation in the 1908 Drury Lane pantomime, with his popular tongue-twister, ‘She sells sea shells on the sea shore’.

2 Albert’s tie dilemma recalls the description of Rosie’s outfit in ‘The Spring Frock’ which ‘had no poetry, no meaning, no chic, no je-ne-sais-quoi’ (The Strand Magazine, December 1919).

3 The play on the literal and figurative meanings of ‘stout’ and ‘stouter’ reappears in ‘Honeysuckle Cottage’ (1925), repr. in Meet Mr Mulliner (1927).

4 ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever’, John Keats, ‘Endymion’ (1818).

A page from Tit-Bits, ‘Answers to correspondents’, 15 August 1908. Note the appearance of ‘Not George Washington’ as the pseudonym of the ‘Independence Day’ correspondent.

TO WILLIAM TOWNEND

May 6. 1908

Dear Bill.

Here’s a go. I’ve been commissioned by Chums to do a serial (70,000 words) by July. They want it not so public-schooly as my usual, & with rather a lurid plot. For Heaven’s sake rally to the old flag & lend a hand with the plot.1 I’ve written off today earnestly recommending you for the pics on the strength of The White Feather, & this time I think it really may come off (Beroofen),2 as I am to them practically old man Kip doing the story as a bally favour.3

In any case, give me an idea or two for the plot. I enclose root idea.

I have asked them to write to you. If they give you the pics to do, wire to me at once, as it will buck me up.

Yours

PGW

P.S. Your reward will be my blessing & at least a fiver, as in case of Lost Lambs, which, by the way, I have only just finished with incredible sweat.4

RSVP

1 PGW’s commission was to become The Luck Stone, published under the pseudonym Basil Windham. Chums published the serial in nineteen weekly instalments from September 1908 to January 1909.

2 Unberufen – ‘touch wood’ (German). The joke can be traced back to an 1891 Punch sketch. PGW uses ‘beroofen’ again in The Gem Collector (1909; US title, The Intrusion of Jimmy), and still remembers it in 1934 for Aunt Dahlia in Right-Ho, Jeeves.

3 Old Man Kip – Rudyard Kipling. See ‘The Sing-Song of Old Man Kangaroo’, in Just-So Stories (1902). Though he was only forty-three years old in 1908, Kipling’s success made him, in PGW’s eyes, one of the grand old men of the literary establishment.

4 The Lost Lambs (which was later to become the second part of Mike) was published in The Captain from April to September 1908.

Wodehouse’s Love Among the Chickens, in American serialised form.

The Luck Stone was not as great a success as Wodehouse’s other works. ‘Although the plot is excellent’, his publisher noted, ‘the general atmosphere is hardly up to the standard of Mike.’ The manuscript was sent back to Wodehouse, with a request that he rewrite it with a view to turning it into a novel. As the decade drew to a close, Wodehouse headed for New York and attempted to track down his American literary agent, A. E. Baerman, who had promised (but not delivered) a $1,000 advance on an American edition of Love Among the Chickens. The novel was described by a reviewer as ‘a merry tale, cleverly told’ full of ‘ludicrous situations […] kept in fine restraint’. In the battle of Westbrook v. Wodehouse, Wodehouse had won hands down. Now he needed to find his way in New York, alone.

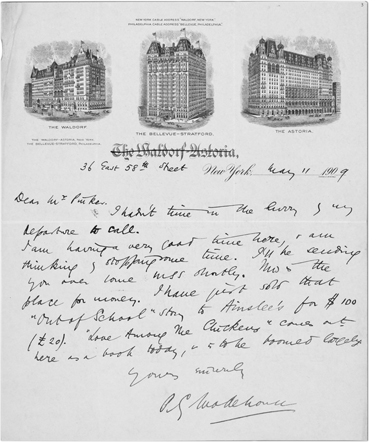

TO J. B. PINKER

36 East 58th Street

New York

May 11. 1909

Dear Mr Pinker.

I hadn’t time in the hurry of my departure to call.

I am having a very good time here, & am thinking of stopping some time. I’ll be sending you over some MSS shortly. This is the place for money. I have just sold that ‘Out of School’ story to Ainslee’s for $100 (£20). Love Among the Chickens comes out here as a book today, & is to be boomed largely.

Yours sincerely

P. G. Wodehouse.

P. G. Wodehouse to J. B. Pinker, 11 May 1909.