Wodehouse and Ethel had only known each other a few weeks when they were married in the Little Church Round the Corner, off Madison Square on East 29th Street. Their courtship was shot through with comedy. An early date was cut short because Wodehouse had toothache; a fit of sneezing overcame him at the moment he tried to propose; and the marriage ceremony itself was delayed because the minister was busy making a killing on the stock market. But their feelings for each other were serious. Ethel was, for Wodehouse, an ‘angel in human form’.1 This unlikely union, between two lonely English people, could be put down to ‘what the unthinking call coincidence’.2 But while chance played a part, there was more to it than that. Four years younger than Wodehouse, Ethel Rowley Wayman was an astute and clever woman. Described as a ‘mixture of Mistress Quickly and Florence Nightingale with a touch of Lady Macbeth thrown in’, she always worked to turn contingency to opportunity.3 Handsome, long-legged, glamorous and intensely sociable, she was in many ways Wodehouse’s opposite – but she understood him well.

Ethel’s spirited nature proved to be a triumph of sorts [see plate 21]. She had not had a straightforward life. Born in Norfolk, with the given name Ethel Newton, she was the illegitimate daughter of a farmer and a milliner. She disliked her mother, who was an alcoholic, and was looked after partly in care, and partly by her maternal grandmother. In her teens, she began to earn her living as a dancer, and it was in 1903, while she was working in Blackpool for the summer season, that she became pregnant. The father, Leonard Rowley, was a university student studying engineering. To avoid scandal, the pair swiftly married. A year later, while Wodehouse was still making his way in the world of London journalism, the Rowleys – and their daughter, Leonora – set off for Mysore in India, where Leonard was to work as an engineer. He died in 1910, in obscure circumstances, believed to be due to drinking infected water.

Left to provide for her seven-year-old daughter, Ethel returned to England. By January of the following year, she married again. She was soon to be twice-widowed. Her second husband, a London tailor called John Wayman, became bankrupt after a failed business venture, and committed suicide. Ethel returned to the career she knew best – the stage. Placing Leonora in a boarding school, she began a series of trips to America, appearing as an ‘artiste’ in various repertory and variety productions under the stage-name ‘Ethel Milton’ [see plate 16].

If not a socialist, Wodehouse had always been, in his own way, an emancipated novelist. So many of his novels would go on to show the butler commanding the aristocrat, the chorus-girl triumphing over the debutante. Much of this came from Wodehouse’s own innate sense of justice and equality. Part of the attraction of America, for him, was its real sense of ‘knockabout’ democracy, in which a college professor and a barman could laugh at the same thing. In 1915, he gave an interview in which he passionately argued that British comic writing was hampered by its class-bound nature. The best humour, he commented, ‘is universal’.4 The force of this must have been felt all the more once he had met Ethel. For though she was only to speak of this privately, she – like the inimitable Sue Brown and the intrepid Jill Mariner – was a chorus-girl who came from nowhere.

In marrying Ethel, Wodehouse not only gained a wife. He also ‘inherited’ Leonora, her daughter [see plate 17]. He first met his new step-daughter in the spring of 1915, when she was eleven years old. They immediately became close, and he formally adopted her that year.

Leonora soon joined the Wodehouses in Long Island, went to school in America for a time, and spent her holidays riding her bicycle around the local roads. Wodehouse adored Leonora. The early US edition of Piccadilly Jim is dedicated ‘To my step-daughter Lenora [sic], conservatively speaking the most wonderful child on earth’, while Leave It to Psmith is ‘For my daughter, Leonora, Queen of her Species’. Indeed, Wodehouse’s 1914 satire on the fashion for eugenic family planning (The White Hope) was oddly prescient. Family, for Wodehouse, was forged through love, not genetics. Leonora – or ‘Snorky’ – as she soon became, was far more precious to Wodehouse than any of his biological relations.

Wodehouse and Ethel had little money when they married. She ‘had seventy dollars’ and ‘I had managed to save fifty’, he recalls – but the letters record them being all the happier for their makeshift existence together. This was an intensely productive time for Wodehouse. He was appointed drama critic for Vanity Fair, wrote numerous feature articles, and sold many of his stories to top magazines.

Crucially – in 1915 – a serial was bought by the top ‘slick’ paper, the Saturday Evening Post. Something Fresh (published in America as Something New), the tale of hard-up Ashe Marson and the enterprising Joan Valentine, marked Wodehouse’s arrival as a major writer in America. The first of his Blandings Castle saga, this was just the beginning of many more appearances by the absent-minded Earl of Emsworth and the dread Lady Constance Keeble. The writing of this was, Wodehouse recalls, ‘a turning point’: ‘It gave me confidence and I suddenly began to write much better.’5

The year 1915 was also important for Wodehouse as it saw the first appearance of two of his most memorable characters. The Saturday Evening Post story ‘Extricating Young Gussie’ features a ‘drone’, Bertie Wooster, making ‘his formal bow, not very forcefully assisted by Jeeves, whose potential was yet to be realised’.6 Writing fifty years later, Wodehouse commented that ‘I find it curious, now that I have written so much about him, to recall how softly and undramatically Jeeves first entered my little world. Characteristically he did not thrust himself forward.’7

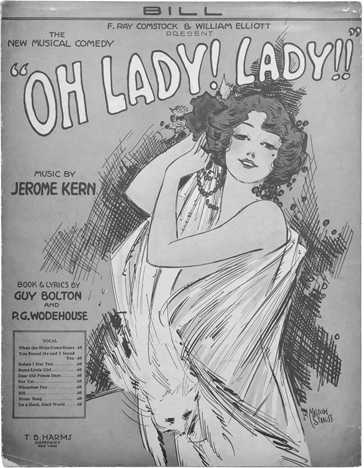

But Wodehouse was thrusting forward at quite a rate. His greatest opportunity came not in the field of novel writing, but in that of musical theatre. While he had already had some small success, writing occasional lyrics for musicals in London, the years from 1916 to 1918 were in a different league. This was his great period of collaboration with the British-American librettist Guy Bolton (1884–1979) and the New York composer Jerome Kern (1885–1945). Kern, who was at this point a rising star, would go on to write such songs as ‘Ol’ Man River’, ‘All the Things You Are’ and ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’. Wodehouse later recalled that ‘Guy and I clicked from the start like Damon and Pythias.’8 The ‘trio of musical fame’ collaborated on a series of hits known as the ‘Princess’ musicals that included Miss Springtime (1916), Have a Heart (New York, 1917), Oh, Boy! (New York, 1917), Leave It to Jane (New York, 1917), and Oh, Lady! Lady!! (New York, 1918) [see plate 20]. They toured these musicals across the eastern states of America – testing their success with audiences and refining the music and lyrics – before opening in New York.

The cover of the sheet music for Wodehouse and Kern’s song ‘Bill’, first performed in 1918.

Wodehouse was an extraordinarily talented lyricist. ‘Ten years of training in repression, and the worship of good form at public school’, as he admitted, beat sentiment out of a man.9 But the presence of music allowed him to capture moments of feeling with great tenderness, as shown in perhaps his best-known lyric, ‘Bill’.

Despite his new-found personal happiness and success, Wodehouse knew all too well the daily devastation that was taking place in Europe. The darkness leaves no trace in the fiction of this period – save, perhaps, for the comic figure of Willie Partridge, the enthusiastic bomb-maker in Piccadilly Jim. Wodehouse’s letters touch on war from time to time. He considers the Zeppelin threat; there is a mention of his friend, Thwaites, who had been shot through the neck; he worries about the old Dulwich boys who were still on the front; he frets that his friend Lily will not get enough to eat. But, characteristically, Wodehouse can never bear to brood on pain for long.

1 ‘Preface’ (1969), Something Fresh (1915).

2 Something Fresh, Chapter 4.

3 Malcolm Muggeridge, Chronicles of Wasted Time, quoted in Phelps, p. 104.

4 Interview with Joyce Kilmer, The New York Times, 7 November 1915.

5 PGW to Richard Usborne, 21 May 1956 (Wodehouse Archive).

6 Jasen, p. 56.

7 The World of Jeeves (London: Jenkins, 1967), p. viii.

8 Performing Flea (London: Jenkins, 1953), p. 14.

9 Kilmer.