8

THE EARLY STAGES OF THE FRENCH PROTECTORATE

There are several ways of looking at the years of French hegemony over Cambodia. One is to break them into phases and to trace the extension and decline of French control. Another would examine the period and its ideology and practice—political, economic, educational, and so forth—from a French point of view. A third would treat the period as part of Cambodian history, connected to the times before and after French protection. Now that the French are gone, the third perspective seems the most attractive. Although there are serious gaps in the sources and although useful primary material in Khmer aside from royal chronicles is very scarce, in this chapter I attempt to see the French as often as possible through Cambodian eyes.

In the meantime, if we look at the colonial era in terms of the waxing and waning of French control (the first of the three perspectives), the years break fairly easily into phases. The first phase lasted from the establishment of the protectorate in 1863 to the outbreak of a national rebellion in 1884. The second phase would extend from the suppression of the rebellion in 1886 to King Norodom’s death in 1904 when a more cooperative monarch, Norodom’s half-brother, Sisowath, came to the throne. The third phase lasted until Norodom Sihanouk’s coronation in 1941 and spans the reigns of Sisowath (r. 1904–27) and his eldest son, Monivong (r. 1927–41). This period, it can be argued, was the only systematically colonial one in Cambodian history, for in the remainder of the colonial era (1941–53) the French were concerned more with holding onto power than with systematizing their control.

From a Cambodian perspective, however, it is possible to take the view that the colonial era falls into two periods rather than four, with the break occurring at Sisowath’s coronation in 1906. From that point on, Cambodians stopped governing themselves, and the Westernization of Cambodian life, especially in the towns, intensified. What would have been recognizable in a sruk in 1904 to a Cambodian official of the 1840s had been modified sharply by 1920, when the French government, particularly at the local level, had been organized as part of a total effort in Indochina.

But until the late 1940s, I suspect, few Cambodians would have considered these mechanical changes, or the French presence as a whole, as having a deleterious effect on their lives or on their durable institutions of subsistence farming, family life, Buddhism, and kingship. The political stability that characterized most of the colonial era can be traced in part to French patronage of the king and the king’s patronage of the sangha, which tended to keep these two institutions aligned (politically, at least) with French objectives—partly because kings, monks, and officials had no tradition of innovative behavior and partly because heresy and rebellion, the popular methods of questioning their authority, had been effectively smothered by the French since the 1880s. In terms of economic transformations, the significant developments that occurred in the technology of rice farming tended to be limited to the northwestern part of the kingdom, where huge rice plantations had come into being. In the rest of the country, as Jean Delvert has shown, the expanding population tended to cultivate rice in small, family-oriented plots, as they seem to have done since the times of Chenla.1

Because of this stability, perhaps, many French writers tended to romanticize and favor the Cambodians at the expense of the Vietnamese. At the same time, because in their terms so little was going on, they also tended to look down on the Cambodians as “lazy” or “obedient.” An ambiguous romanticism suffuses many French-language sources on the colonial era, especially in the twentieth century, when clichés about the people were passed along as heirlooms from one official (or one issue of a newspaper) to the next. At the same time, until the early 1940s, no Cambodian-language sources questioned the efficacy of French rule or Cambodia’s traditional institutions.

For these reasons it is tempting to join some French authors and skip over an era when “nothing happened.” But to do so would be a mistake because what was happening, especially after the economic boom of the 1920s, was that independent, prerevolutionary Cambodia (with all its shortcomings) was being built or foreshadowed despite large areas of life that remained, as many French writers would say, part of the “timeless” and “mysterious” Cambodia of Angkor.

It is tempting also to divide French behavior in Cambodia into such categories as political, economic, and social, terms that give the false impression that they are separable segments of reality. What the French meant by them in the context of the colonial situation tended to be idiosyncratic. Politics, for example, meant dissidence and manipulation rather than participation in an open political process. Ideally, in a colony there should be no politics at all. Economics meant budgets, taxes, and revenues—in other words, the economics of bureaucratic control. On the rare occasions when French writers looked at Cambodia’s economy, they related it to the rest of Indochina, particularly in terms of export crops and colonial initiatives like public works, rather than to Cambodian needs and capabilities. By the 1920s, in the eyes of French officials, Cambodia had become a rice-making machine, producing revenue in exchange for “guidance.” This meant that the essence of government—rajakar, or “royal work”—remained what it had always been, the extraction of revenue from the peasants. As for social, the word as the French used it did not refer to solidarity among people or relationships that added up to political cohesion. Instead, society meant a conglomeration of families, obediently at work.

The chronological perspective and the analytical ones just mentioned may be helpful in examining the colonial era because looking at these years in terms of Cambodian history means looking at them in terms of continuity and change. From this angle, the alterations to Cambodian society and the thinking of the Cambodian elite are as important as the apparently timeless life in the villages, which was also changing.

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE FRENCH PROTECTORATE

The beginnings of French involvement in Cambodia are to be found in the eighteenth century, when Catholic missionaries took up residence in the kingdom, especially in the vicinity of Udong. French involvement did not become political, however, before the 1850s, coincident with French involvement in Vietnam. In the mid-1850s King Duang sought French support in an attempt to play off the Thai against the Vietnamese, but a French diplomatic mission to Cambodia in 1856, armed with a draft treaty of cooperation, failed to reach the Cambodian court, which was frightened away from welcoming it by Thai political advisers. The draft treaty, incidentally, contained several clauses that passed into the operative one concluded in 1863. The French wanted teak for shipbuilding, for example, as well as freedom to move about the country and freedom to proselytize for the Roman Catholic faith.2

French interest in Cambodia deepened with their involvement in Vietnam and also after a French naturalist, Henri Mouhot (1826–61), visited Duang’s court and then proceeded to Siem Reap, where he discovered the ruins of Angkor. Mouhot suggested in a posthumously published book about his travels that Cambodia was exceptionally rich and that its rulers were neglecting their patrimony.3 Duang’s openness to Mouhot and to other European visitors in this period stemmed in part from his friendship with a French missionary, Monseigneur Jean Claude Miche, whose mission headquarters was located near Udong and who had actively supported the 1856 diplomatic mission. Miche convinced the king that there could be advantages in being free from Thai control and Vietnamese threats. In the last two years of his reign, moreover, Duang also saw French expansion into Vietnam as an opportunity for him to regain territory and Khmer-speaking people lost to the Vietnamese over the preceding two hundred years.4

Bogged down in guerrilla warfare in Vietnam and unsure of support from Paris, the French administrators in Saigon were slow to respond to Cambodia’s assertions of friendship. The matter lapsed when Duang died in 1860 and Cambodia was plunged into a series of civil wars. Duang’s designated heir, Norodom, was unpopular in the eastern sruk and among Cham dissidents, who had almost captured Udong while Duang was alive. Norodom had spent much of his youth as a hostage at the Thai court. Unable to rule, he fled Cambodia in 1861, returning with Thai support at the end of the following year. But he returned on a probationary basis, for his royal regalia remained in Bangkok. Angered by Thai interference and attracted by French promises of gifts, Norodom reopened negotiations with the French. According to a contemporary, the French admiral in charge of southern Vietnam, “having no immediate war to fight, looked for a peaceful conquest and began dreaming about Cambodia.”5

The colonial era began without a shot and in a tentative way. A delegation of French naval officers concluded a treaty with Norodom in Udong in August 1863, offering him protection at the hands of a French resident in exchange for timber concessions and mineral exploration rights. Norodom managed to keep the treaty secret from his Thai advisers for several months. When they found out about it and notified Bangkok, he quickly reasserted his dependence on the Thai king, declaring to his advisers, “I desire to remain the Thai king’s servant, for his glory, until the end of my life. No change ever occurs in my heart.” The Thai, in turn, kept Norodom’s change of heart a secret from the French, who learned of it only after his earlier declaration of faith had been ratified in Paris in early 1864.6

What Norodom wanted from the French vis-à-vis the Thai is unclear. He seems to have been playing for time, and the method he chose resembled that of his uncle, King Chan, with the French in the role of the Vietnamese. He also wanted to be crowned, and by the middle of 1864, the Thai and the French had agreed to cosponsor his coronation. The unintentionally comical aspects of the ceremony are recounted by several French sources. Thai and French officials quarreled about precedent, protocol, and regalia while Norodom, using time-honored filial imagery, proclaimed his dependence on both courts. For the last time, the Cambodian king’s titles were chosen and transmitted by Bangkok; for the last time, too, the Cambodian king claimed to draw legitimacy from two foreign courts. For the first time, a Cambodian king accepted his crown from a European. The next three Cambodian monarchs followed suit. From this point on, Thai influence in Cambodia began to wane, fading even more sharply and more or less for good after King Mongkut died in 1867.7

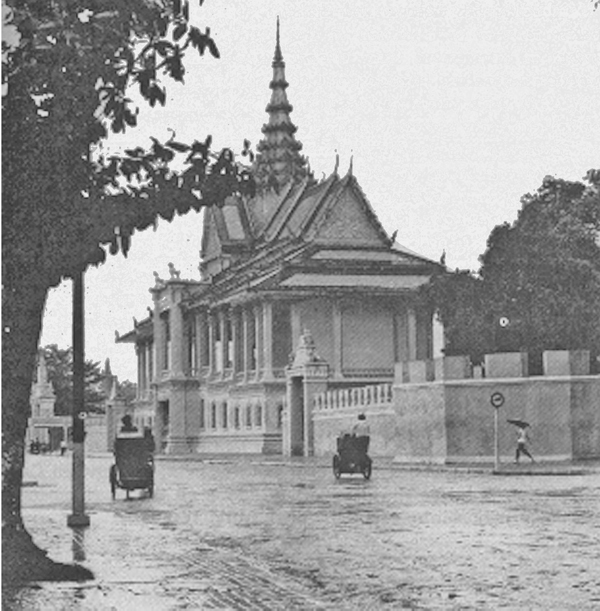

The imposition of French protection over Cambodia did not end the dynastic and millenarian rebellions that had plagued the beginning of Norodom’s reign, although French military forces were helpful in quelling these rebellions by 1867. The most important of them was led by Pou Kombo, an ex-monk who claimed that that he had a better right than Norodom to be king. A year before, Norodom had shifted his palace to Phnom Penh. He had been urged to do so by the French, just as Chan had been encouraged to move by the Vietnamese earlier in the century, and for similar tactical reasons. In the French case, commercial motives were also at work, for Phnom Penh was more accessible from Saigon than an inland capital would have been, and it was hoped that the exploration of the Mekong River under Commandant E. Doudart de Lagrée (1823–68) would result in data about the river’s northern reaches that would justify French pipe dreams of Phnom Penh as an important commercial city.8

For the French the 1860s and 1870s were a heroic period, partly because government remained largely in the hands of young naval officers hungry for glory, eager for promotion, and entranced by the exotic setting in which they found themselves. By and large, these omnicompetent pioneers of colonialism—Doudart de Lagrée, Francis Garnier, Jean Moura, and Etienne Aymonier, among others—possessed great energy, intellectual integrity, and sympathy for ordinary Khmer. They explored the Mekong, translated Cambodian chronicles, deciphered inscriptions, and arranged for the shipment of tons of Cambodian sculpture to museums in Paris, Saigon, and eventually Phnom Penh. The grandeur of their exploits and of Cambodia’s distant past formed a sharp contrast in their minds with what they regarded as the decay of the Cambodian court and the helplessness of the Cambodian people. At the same time, as Gregor Muller has shown, the protectorate in its early years was plagued by unscrupulous French adventurers posing as entrepreneurs and eager to capitalize on royal cupidity and the ambiguities of French control.9

There was probably little difference, however, between the way Cambodia was governed in the 1860s and 1870s and the way Angkor had been governed almost a thousand years before. In both cases, perhaps, and certainly for most of the years between, government meant a network of status relationships and obligations whereby peasants paid in rice, forest products, or labor to support their officials in exchange for their protection. The officials, in turn, paid the king, using some of the rice, forest products, and peasant labor with which they had been paid. Entrepreneurs—often Chinese, occasionally French—paid the king for the right to market and export the products. The number of peasants one could exploit in this way depended on the positions granted by the throne, positions that were themselves for sale. Officeholders in such a system tended to be members of the elite with enough money or goods on hand to purchase and protect their positions.

THE TIGHTENING OF FRENCH CONTROL

Within the palace, Norodom governed Cambodia in what the French considered to be an arbitrary, authoritarian way. The French, however, offered him no alternative style, and throughout his reign Norodom was drawn less by the idea of a sound administration than by what he considered to be the imperatives of personal survival. Revolts against his rule (and implicitly against his acquiescence to the French) broke out in 1866–67 and in the 1870s. Both attracted considerable support, and the French put both down with difficulty. Unwilling to blame themselves for this state of affairs, the French blamed Norodom and were increasingly drawn to support his half-brother, Sisowath, who had led troops alongside the French in both rebellions.

Under French pressure and while another half-brother, Siwotha, was in revolt against him, Norodom agreed in 1877 to promulgate a series of reforms. Although these were never carried out, they are worth noting as precursors of more extensive French control and as indications of areas of French concern. The reforms sought to dismantle royal involvement in landownership, to reduce the number of okya, to rationalize tax collection, and to abolish slavery. Had they been enacted, they would have worn away the power bases of the Cambodian elite. Like Minh Mang in the 1830s, the French disliked the Cambodian way of doing things, which interfered with their ideas of rational, centralized control. Institutions like slavery and absolute monarchy, moreover, went down poorly with officials of the Third Republic, less charmed by the romantic operetta aspects of Cambodia than Napoleon III and his entourage had been.

In the early 1880s, as the French tightened their grip on Vietnam, it was only a matter of time before they solved what they saw as Cambodia’s problems and imposed their will on the Cambodian court. The comedy in Phnom Penh had gone on too long and had cost the French too much. The Cambodians had not seen the importance of paying for French protection. The French became impatient and assumed for this reason that time was running out. The riches of Cambodia remained largely untapped. What had seemed exotic and quaint in Cambodian society in the 1860s and 1870s was now seen by a new generation of civilian officials as oppressive; it was time for protection to become control.

In 1884 the French succeeded in getting Norodom to agree to siphon off customs duties, especially on exports, to pay for French administrative costs. Norodom sent a cable to the president of France protesting French pressure and was chided for doing so by the governor-general of Cochin China, Charles Thomson, who had been negotiating secretly with Sisowath to arrange a transfer of power should Norodom prove resistant to the reforms.10

A few months later, Thomson sailed from Saigon to Phnom Penh and confronted Norodom with a wide-ranging set of reforms encased in a treaty that went further than previous documents had to establish de jure French control. Thomson arrived at the palace unannounced one day at 10 p.m., traveling aboard a gunboat that was anchored within sight of the palace. As Norodom reviewed the document, Thomson’s armed bodyguards stood nearby. Aided by a complaisant interpreter, Son Diep, who rose to bureaucratic heights after Norodom’s death, the king signed it because he saw that doing so was the only way to stay on the throne; he undoubtedly knew of Sisowath’s machinations. Perhaps he thought that the document’s provisions would dissolve when the French encountered opposition to the provisions from the Cambodian elite. This is, in fact, what happened almost at once, but Article 2 of the treaty nevertheless marked a substantial intensification of French control. As it read, “His Majesty the King of Cambodia accepts all the administrative, judicial, financial, and commercial reforms which the French government shall judge, in future, useful to make their protectorate successful.”11

It was not this provision, however, that enraged the Cambodian elite, who by that time probably viewed Norodom as a French puppet. The features they saw as revolutionary (and that the French saw as crucial to their program of reforms) were those that placed French résidents in provincial cities, abolished slavery, and institutionalized the ownership of land. These provisions struck at the heart of traditional Cambodian politics, which were built up out of entourages, exploitation of labor, and the taxation of harvests (rather than land) for the benefit of the elite, who were now to become paid civil servants of the French, administering rather than consuming the people under their control.

Although few French officials had taken the trouble to study what they referred to as slavery in Cambodia, and although their motives for abolishing it may have included a cynical attempt to disarm political opposition in France to their other reforms, it is clear that the deinstitutionalization of servitude was a more crucial reform, in Cambodian terms, than the placement of a few French officials in the countryside to oversee the behavior of Cambodian officials. Without this reform the French could not claim to be acting on behalf of ordinary people. More importantly, they could do nothing to curb the power of the perennially hostile Cambodian elite, which sprang from who controlled personnel. Without abolishing slavery, moreover, the French could not proceed with their vision—however misguided it may have been—of a liberated Cambodian yeomanry responding rationally to market pressures and the benefits of French protection.

By cutting the ties that bound masters and servants—or, more precisely, by saying that this was what they hoped to do—the French were now able to justify their interference at every level of Cambodian life. Their proposal effectively cut the king off from his entourage and this entourage, in turn, from its followers. The French wanted Cambodia to be an extension of Vietnam, with communal officials responding directly to the French, even though government of this sort and at this level was foreign to Cambodia, where no communal traditions—had they ever existed—survived into the nineteenth century.

In the short run the Cambodian reaction to the treaty was intense and costly to the French. In early 1885 a nationwide rebellion, under several leaders, broke out at various points.12 It lasted a year and a half, tying down some four thousand French and Vietnamese troops at a time when French resources were stretched thin in Indochina. Unwilling to work through Norodom, whom they suspected of supporting the rebellion, the French relied increasingly on Sisowath, allowing him a free hand in appointing pro-French officials in the sruk, further undermining Norodom’s authority. It seems likely that Sisowath expected to be rewarded with the throne while Norodom was still alive, but as the revolt wore on the French found that they had to turn back to Norodom to pacify the rebels. In July 1886 the king proclaimed that if the rebels laid down their arms, the French would continue to respect Cambodian customs and laws—in other words, the mixture as before. The rebellion taught the French to be cautious, but their goals remained the same—to make Canbodian governance more rational and to control the kingdom’s economy. It was at this stage that the French began to surround Norodom with Cambodian advisers who were loyal to them rather than to the king. These were drawn, in large part, from the small corps of interpreters trained under the French in the 1870s. The most notable of them was a Sino-Khmer named Thiounn, who was to play an important role in Cambodian politics until the 1940s.

The issue at stake in the rebellion, as Norodom’s chronicle points out, was that the “Cambodian people were fond of their own leaders,” especially because alternatives to them were so uncertain. A French writer in the 1930s blamed the French for their hastiness in trying to impose “equality, property, and an electorate,”13 because Cambodians were supposed to choose their own village leaders under an article of the treaty. He added that, in fact, “the masters wanted to keep their slaves and the slaves their masters”; people clung to the patron-client system that had been in effect in Cambodia for centuries.

Faced with the possibility of a drawn-out war, the French stepped back from their proposed reforms. Although the treaty was ratified in 1886, most of its provisions did not come into effect for nearly twenty years, after Norodom was dead.

At the same time, it would be wrong to exaggerate this Cambodian victory or to agree with some Cambodian writers in the early 1970s who saw the rebellion as a watershed of Cambodian nationalism, with Norodom cast as a courageous patriot cleverly opposing French control. The evidence for these assertions is ambiguous. Norodom, after all, accepted French protection in a general way but attacked it when he thought his own interests, especially financial ones, were at stake. There is little evidence that he viewed his people as anything other than objects to consume, and certainly the French distrusted him more than ever after 1886. They spent the rest of his reign reducing his privileges and independence. But it would be incorrect to endow Norodom or the rebellious okya with systematic ideas about the Cambodian nation (as opposed to particular, personal relationships).

With hindsight we can perceive two important lessons of the rebellion. One was that the regional elite, despite French intervention in Cambodia, was still able to organize sizable and efficient guerrilla forces, as it had done against the Thai in 1834 and the Vietnamese in 1841; it was to do so again in the more peaceable 1916 Affair discussed in Chapter 9. The second lesson was that guerrilla troops, especially when supported by much of the population, could hold a colonial army at bay.

The next ten years of Norodom’s reign saw an inexorable increase in French control, with policies changing “from ones of sentiment . . . to a more egotistic, more personal policy of colonial expansion.”14 All that stood in the way of the French was the fact that Norodom still made the laws, appointed the officials, and controlled the national economy by farming out sources of revenue (such as the opium monopoly and gambling concessions), by demanding gifts from his officials, and by refusing to pay his bills. By 1892, however, the collection of direct taxes had come under French control; two years later, there were ten French résidences in the sruk. The 1890s, in fact, saw increasing French consolidation throughout Indochina, culminating in the governor-generalship of Paul Doumer (1897–1902).

In Cambodia this consolidation involved tinkering with fiscal procedures and favoring Sisowath rather than any of Norodom’s children as the successor to the throne. French officials wanted Norodom to relinquish control but were frightened by the independent-mindedness of many of his sons, one of whom was exiled to Algeria in 1893 for anticolonial agitation. The king’s health was poor in any case and was made worse by his addiction to opium, which the French provided him in ornamental boxes free of charge. As French officials grew more impatient with Norodom and as he weakened, they became abusive. After all, there were fortunes to be made by colonists in Cambodia, or so they thought, and Norodom barred the way. The climax came in 1897 when the résident supérieur, Huynh de Verneville, cabled Paris that the king was incapable of ruling the country. Verneville asked to be granted executive authority, and Paris concurred. The résident was now free to issue royal decrees, appoint officials, and collect indirect taxes. As Milton Osborne has pointed out, high-ranking Cambodian officials, previously dependent on Norodom’s approval, were quick to sense a shift in the balance of power.15 By the end of the year, the king’s advice—even though he had now regained his seals and Verneville had been dismissed—was heeded only as a matter of form; the new résident supérieur was in command, answerable to authorities in Saigon, Paris, and Hanoi. What was now protected after a thirty-year tug-of-war between Norodom and the French, was not Cambodia, its monarch, or its people, but French colonial interests.

In the meantime, long-postponed royal decrees, such as one that allowed French citizens to purchase land, had produced a real estate boom in Phnom Penh. The effect of the reforms in the sruk, as far as we can tell, was less far-reaching. Throughout the 1890s, French résidents complained officially about torpor, corruption, and timidity among local officials, although one of the latter, sensing the tune he was now expected to play, reported to his French superiors that “the population of all the villages in my province is happy; [the people] have not even the slightest complaint about the measures that have been taken.”16 The Cambodian countryside, however, as many French officials complained, remained a terra incognita. No one knew how many people it contained, what they thought, or who held titles to land. Although slavery had been abolished, servitude for debts—often lasting a lifetime—remained widespread. Millenarian leaders occasionally gathered credulous followers and led them into revolt; in the dry season, gangs of bandits roamed the countryside at will. At the village level, in fact, conditions were probably no more secure than they had ever been.

And yet, many high-ranking French officials still saw their role in the country in terms of a civilizing mission and of rationalizing their relationships with the court. In the countryside, ironically, Sisowath was more popular than Norodom, partly because the people had seen him more often, on ceremonial occasions, and partly because Norodom’s rule had been for the most part rapacious and unjust. Sisowath, in fact, looked on approvingly at developments in the 1890s, and by 1897 or so French officials had formally promised him the throne.

Norodom took seven more years to die. The last years of his reign were marked by a scandal involving his favorite son, Prince Yukanthor, who sought to publicize French injustice in Cambodia when he was in France by hiring a French journalist to press his case with French officialdom. Officials paid slight attention, except to take offense. Yukanthor’s accusations were largely true, if perhaps too zealous and wide-ranging, as when he declared to the people of France, “You have created property in Cambodia, and thus you have created the poor.”17

Officials in Paris persuaded Norodom by cable to demand an apology from his son. It never came, for Yukanthor preferred to remain in exile. He died in Bangkok in 1934 and until then was viewed by French colonial officials with slight but unjustified apprehension.

The two last prerogatives that Norodom surrendered to the French were the authority to select his close advisers and the right to farm out gambling concessions to Chinese businessmen in Phnom Penh. Little by little, the French reduced his freedom of action. Osborne has recorded the battles that Norodom lost, but the last pages of the royal chronicle (compiled during the reign of Sisowath’s son, King Monivong, in the 1930s) say almost nothing about the confrontation, leaving the impression that the reign was moving peacefully and ceremoniously toward its close.

SISOWATH’S EARLY YEARS

Norodom, like millions of people of his generation, was born in a village and died in a semimodern city, graced at the time of his death with a certain amount of electricity and running water. The modernization of the edges and surfaces of his kingdom, however, spread very slowly. Communications inside Cambodia remained poor; monks, royalty, and officials—the people held in most respect—resisted institutional change; and the so-called modernizing segment of the society was dominated by the French, aided by immigrants from China and Vietnam. The modernizers, interestingly, thought in Indochinese terms, or perhaps in capitalist ones, while members of the traditional elite saw no reason to widen their intellectual horizons or to tinker with their beliefs.

Norodom’s death, nonetheless, was a watershed in French involvement and in Cambodian kingship as an institution, as the French handpicked the next three kings of the country. Until 1953, except for a few months in the summer of 1945, high-ranking Cambodian officials played a subordinate, ceremonial role, and those at lower levels of the administration were underpaid servants of a colonial power. At no point in the chain of command was initiative rewarded. While Norodom lived, the French encountered obstacles to their plans. After 1904, with some exceptions, Cambodia became a relatively efficient revenue-producing machine.

The change over the long term, which is easy to see from our perspective, was not immediately perceptible in the sruk, where French officials found old habits of patronage, dependence, violence, fatalism, and corruption largely unchanged from year to year. Offices were still for sale, tax rolls were falsified, and rice harvests were underestimated. Credulous people were still ready to follow sorcerers and mountebanks. As late as 1923 in Stung Treng, an ex-monk gathered a following by claiming to possess a “golden frog with a human voice.”18 Banditry was widespread, and there were frequent famines and epidemics of malaria and cholera. The contrast between the capital and the sruk, therefore, sharpened in the early twentieth century, without apparently producing audible resentment in the sruk, even though peasants in the long run paid with their labor and their rice for all the improvements in Phnom Penh and for the high salaries enjoyed by French officials, fueling the resentment of anti-French guerrillas in the early 1950s and Communist cadres later on.

When Sisowath succeeded his brother in 1904 he was sixty-four years old. Ever since the 1870s he had been an assiduous collaborator with the French. He was a more fervent Buddhist than Norodom and he was more popular among ordinary people, some of whom associated him with the Buddhist ceremonies that he had sponsored (and that they had paid for) rather than the taxes charged by his brother or by the French. According to one French writer, he was so frightened of his brother, even in death, that he refused to attend his cremation. The first two years of his reign, according to the chronicle, were devoted largely to ceremonial observances and to bureaucratic innovations (such as appointing an electrician for the palace and enjoining officials to wear stockings and shoes in Western style).19 On another occasion, Sisowath harangued visiting officials—probably at French insistence—about the persistence of slavery in the sruk.20 Throughout the year, like all Cambodian kings, he sponsored ceremonies meant to ensure good harvests and rainfall. Each year for the rest of his reign, the French provided Sisowath (as they had Norodom) with an allowance of high-grade opium totaling 113 kilograms (249 pounds) per year.21

This early stage of his reign culminated in Norodom’s cremation in 1906, which was followed almost immediately by Sisowath’s coronation. For the first time in Cambodian history, the ceremony is described in detail in the chronicle (as well as by French sources). It lasted for several days. One of its interesting features was that the French governor-general of Indochina was entrusted with giving Sisowath his titles and handing him his regalia. Another was that the chaovay sruk, summoned to the palace for the occasion, solemnly pledged to the king “all rice lands, vegetable fields, water, earth, forest and mountains, and the sacred boundaries of the great city, the kingdom of Kampuchea.”22

Almost immediately after being crowned, Sisowath left Cambodia to visit the Colonial Exhibition at Marseilles, in the company of the royal ballet troupe.23 His voyage is scrupulously recorded in the chronicle, which makes it sound like an episode in a Cambodian poem, and also in the account of a palace official who accompanied the king. Sisowath’s progress through Singapore, Ceylon, and the Indian Ocean is reverently set down in both texts, and so are gnomic comments about the sights farther on (three-story buildings in Italy, the coastline of the Red Sea consisting of “nothing but sand and rock”). At Port Said, people eagerly came to pay homage to “the lord of life and master of lives in the south.” In Marseilles, when the king made a speech, “All the French people who were present clapped their hands—men and women alike.” The chronicle and the official’s somewhat overlapping account gives the impression that the king decided to visit France; in fact, his visit was forced on him by the requirement of the exposition officials that the royal ballet perform at the Colonial Exhibition.24 From the French point of view, unofficially at least, this visit by an aged potentate and his harem told them what they already “knew” about his exotic, loyal, and faintly comic little country.25

After exchanging visits and dinners with the president of the republic, and a trip to Nancy to observe “the 14th of July in a European way,” the king returned to Cambodia. Although neither the chronicle nor the palace official’s narrative of the voyage mentions discussions of substantive matters, Sisowath’s visit to Paris coincided with Franco-Thai negotiations there that culminated, a few months later, in Siam’s retrocession to Cambodia of the sruk of Battambang and Siem Reap.26 The trip received little publicity at home and is mentioned in French reports from the sruk only in connection with a rumor that Sisowath had gone to France to plead with the French to legalize gambling in Cambodia.

The number of pages in Sisowath’s chronicle devoted to the return of Battambang and Siem Reap suggests that the compilers, like the French, considered this to be the most important event of the reign, even though the king had little to do with it beyond providing the résident supérieur, in 1906, with a history of Thai occupation. The importance of the retrocession was probably connected with the importance that Angkor, and especially Angkor Wat, had retained for the Cambodian monarchy for several centuries.27 In 1909 a copy of the Cambodian translation of sacred Buddhist writings, the Tripitaka, was deposited in a monastery on the grounds of Angkor Wat, and for another sixty years Cambodian monarchs frequently visited the site and sponsored ceremonies there.

As we have seen, the northwestern sruk had come under Thai control in 1794, apparently in exchange for Thai permission for Eng, Sisowath’s grandfather, to rule at Udong. Over the next hundred years, except for a brief period in the 1830s, the Thai made little effort to colonize (or depopulate) the region, choosing to govern it at most levels with ethnic Khmer. Although they did nothing to restore the temples at Angkor, they left them intact. Revenue from the two sruk—in stipulated amounts of cardamom and other forest products—was not especially high, and the region was more defensible by water from Phnom Penh than overland from Bangkok.28

For these reasons, but primarily to avoid further friction along its border, the Thai decided in 1906 to cede the sruk to France. The French and the Thai signed the final agreement in April 1907, and the sruk came under French control toward the end of the year. Sisowath was not encouraged to visit the area, however, until 1909, for reasons that the chronicle fails to make clear.

And yet the king and his subjects were overjoyed at the restoration of Angkor. In the tang tok ceremonies of October 1907, when officials traditionally offered gifts to the monarch, widely attended celebrations occurred throughout the kingdom to “thank the angels” (thevoda) for the return of the sruk, and local officials assigned to the region came to Phnom Penh to pay homage to the king.

Over the next half century, French scholars and Cambodian workers restored the temples at Angkor. In the long run the restoration was probably France’s most valuable legacy to Cambodia. Battambang, especially in the 1920s, developed into the country’s most prosperous sruk, providing the bulk of Cambodia’s rice exports and sheltering, idiosyncratically, the greatest number of landlords in the country as well as the highest number of immigrants from elsewhere in Cambodia and from the Cambodian-speaking portions of Cochin China.29

By 1909, typewriters had been installed in all the résidences; automobiles came into use on a national scale at about the same time. These two improvements in French administration had several unintentional effects. For one thing, the volume of reports required by résidents, and consumed by their superiors in Phnom Penh, Saigon, Hanoi, and Paris, increased dramatically. Résidents, more than ever, were tied down to their offices, presiding over a two-way flow of paper. They were seldom in contact, socially or professionally, with the people they were paid to supposedly civilize and protect. In automobiles, tours of inspection became speedier and more superficial, for résidents, and their aides were confined to passable roads. In fact, the intensification of French economic and political controls over Cambodia, noticeable throughout the 1920s and after, was accompanied, ironically, by the withdrawal of French officials from many levels of Cambodian life. The government that a Cambodian peasant might encounter in these years was composed of a minority of Cambodians and of a great many Vietnamese brought into the protectorate because they could prepare reports in French, and this interplay between Cambodians and Vietnamese had important effects on the development of Cambodian nationalism, especially after World War II.