12

REVOLUTION IN CAMBODIA

It is uncertain whether historians of Cambodia a hundred years from now will devote as much space to the country’s brief revolutionary period as to the much longer, more complex, and more mysterious Angkorean era. For nearly all mature Cambodians in the early twenty-first century, however, the three years, eight months, and twenty days that followed the capture of Phnom Penh in April 1975 were a traumatic and unforgettable period. Because of the ferocity with which Cambodia’s revolution was waged, however, and the way it contrasted with many people’s ideas about pre-1970 Cambodia, a chapter-length discussion of the period fits well in a narrative history of this kind.

The Communist regime that controlled Cambodia between April 17, 1975, and January 7, 1979, was known as Democratic Kampuchea (DK). Survivors remember the time as vinh chu chot (three words for the sharp tastes of unripe fruit). The bitter-tasting revolution that DK sponsored swept through the country like a forest fire or a typhoon, and its spokesmen claimed after the military victory that “over two thousand years of Cambodia history” had ended. So had money, markets, formal education, Buddhism, books, private property, diverse clothing styles, and freedom of movement. No Cambodian government had ever tried to change so many things so rapidly; none had been so relentlessly oriented toward the future or so biased in favor of the poor.

The leaders of DK, who were members of Cambodia’s Communist Party (CPK) were for the most part hidden from view and called themselves the “revolutionary organization” (angkar padevat). They sought to transform Cambodia by replacing what they saw as impediments to national autonomy and social justice with revolutionary energy and incentives. They believed that family life, individualism, and an ingrained fondness for what they called feudal institutions, as well as the institutions themselves, stood in the way of the revolution. Cambodia’s poor, they said, had always been exploited and enslaved. Liberated by the revolution and empowered by military victory, these men and women would now become the masters of their lives and, collectively, the masters of their country.

The CPK monitored every step of the revolution but concealed its existence from outsiders and did not reveal its socialist agenda or the names of its leaders. It said nothing of its long-standing alliance with the Communists in Vietnam and very little about the patronage of China and North Korea that the regime enjoyed. For several months the CPK’s leaders even allowed foreigners to think that Sihanouk, who had served as a figurehead leader for the anti–Lon Nol resistance, was still Cambodia’s chief of state. By concealing its alliances and agendas, the new government gave the impression that Cambodia and its revolution were genuinely independent. In 1978 Saloth Sar (Pol Pot) boasted to Yugoslavian visitors that Cambodia was “building socialism without a model.” That process began in April 1975 and continued for the lifetime of DK, but by acknowledging that there were no precedents for what they were doing, Pol Pot and his colleagues had embarked on a perilous course.1

To transform the country thoroughly and at once, Communist cadres ordered everyone out of the cities and towns. In the week after April 17, 1975, over two million Cambodians were pushed into the countryside toward an uncertain fate. Only the families of top CPK officials and a few hundred Khmer Rouge soldiers were allowed to stay behind. This brutal order, never thoroughly explained, added several thousand deaths to what may have been five hundred thousand inflicted by the civil war. Reports reaching the West spoke of hospital patients driven from their beds, random executions, and sick and elderly people as well as small children dead or abandoned along the roads. The evacuation shocked its victims as well as observers in other countries, who had hoped that the new regime would try to govern through reconciliation. But these men and women may have forgotten the ferocity with which the civil war had been fought by both sides. Still other observers, more sympathetic to the idea of revolution, saw the evacuation of the cities as the only way Cambodia could grow enough food to survive, break down entrenched and supposedly backward-looking social hierarchies, loyalties, and arrangements and set its Utopian strategies in motion.2

The decision to evacuate the cities was made by the CPK’s leaders shortly before the liberation of Phnom Penh, but it was a closely kept secret and took some Communist commanders by surprise. One reason for the decision was that the capital was genuinely short of food. Another was the difficulty of administering several million people who had failed to support the revolution. A third was that the CPK’s leaders were fearful for their own security. Perhaps the overriding reason, however, was the desire to assert the victory of the CPK, the dominance of the countryside over the cities and the empowerment of the poor. Saloth Sar and his colleagues had not spent seven years in the forest and five years after that fighting a civil war to take office as city councilors. They saw the cities as breeding grounds for counterrevolution. Their economic priorities were based on the transformation of Cambodian agriculture, especially on increasing the national production of rice. By exporting the surplus, it was hoped that the government would earn hard currency with which to pay for imports and, eventually, to finance industrialization. To achieve such a surplus, the CPK needed all the agricultural workers it could find.

For the next six months, the people who had been driven out of the cities—known to the regime as “new people” or “April 17 people”—busied themselves with growing rice and other crops under the supervision of soldiers and CPK cadres. Conditions were severe, particularly for those unaccustomed to physical labor, but because in most districts there was enough to eat, many survivors of DK who had been evacuated from Phnom Penh came to look back on these months as a comparative golden age. For the first time in many years, Cambodia was not at war, and many so-called new people were eager to help to reconstruct their battered country. Perhaps, after all, Cambodia’s problems were indeed so severe as to require revolutionary solutions. A former engineer has said, “At first, the ideas of the revolution were good.” He added, however, that “they didn’t work in practice.”3

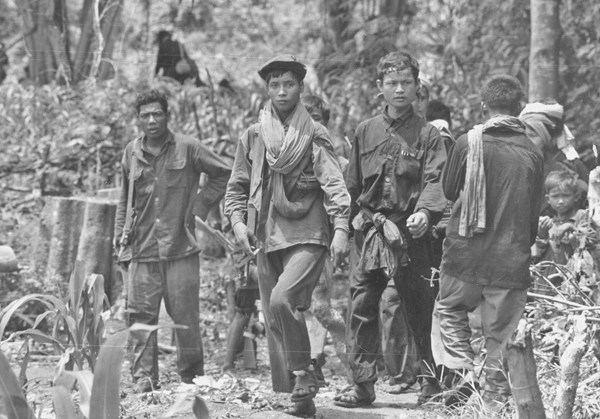

For many rural Cambodians, and especially those between fifteen and twenty-five, fighting against feudalism and the Americans in the early 1970s had provided beguiling glimpses of freedom, self-respect, and power—as well as access to weapons—that were unimaginable to their parents or to most Cambodians. These young people, to borrow a phrase from Mao Zedong, were “poor and blank” pages on which it was often easy to inscribe the teachings of the revolution. Owing everything to the revolutionary organization, which they referred to as their mother and father, and nothing to the past, it was thought that these young people would lead the way in transforming Cambodia into a socialist state and in moving the people toward independence, mastery, and self-reliance. To the alarm and confusion of many older people, these often violent young Cambodians became the revolution’s cutting edge.

DK TAKES POWER, 1975–76

The DK period in Cambodia was characterized by regional and temporal variations. By and large, those parts of the country that had been under CPK control the longest tended to be the best equipped to deal with the programs set out by the party and the most accommodating to the new people. Cadres were better trained and more disciplined in the east, northeast, and southwest than they were in the northwest. Unfortunately for the new people, the northwest, centered on the provinces of Battambang and Pursat, had been the most productive agricultural area in prerevolutionary times. For this reason hundreds of thousands of new people were driven into the northwest in early 1976. The regime’s demands for crop surpluses were heavier there than in other regions, and so were the sufferings that ensued.4

The CPK divided Cambodia into seven zones (phumipheak), which in turn were broken down into thirty-two administrative regions (dombon). In general, conditions were relatively tolerable through 1976 in the northeastern and eastern zones, somewhat worse in the southwest, central, and west, and worst of all in the northern and northwestern zones. Within the zones there was also considerable variation, reflecting differences in leadership, resources, and external factors such as the fighting with Vietnam that broke out in earnest in the east and the southwest in the middle of 1977.5

Life was hard everywhere. On a national scale it is estimated that over the lifetime of the regime nearly two million people—or one person in four—died as a result of DK policies and actions. These included overworking people, neglecting or mistreating the sick, and giving everyone less food than they needed to survive. Perhaps as many as four hundred thousand were killed outright as enemies of the revolution. Most of these people died in provincial prison. On a per capita basis, and considering the short life span of DK, the number of regime-related deaths in Cambodia is one of the highest in recorded world history. Whether or not the death toll fits the terms of the UN genocide convention has been vigorously debated. Those who argue for the use of the term see close parallels in the Cambodian case to what happened during the Holocaust, in Armenia, and in Rwanda. Those arguing against the term suggest that racist motives were much lower on DK’s agenda (except for the systematic execution of Vietnamese residents in 1978 and, in some cases, Muslim Cham) than was destroying the regime’s political enemies, a category of victims purposely omitted from the UN genocide convention. For these critics the term crimes against humanity fits what happened in DK better than the highly charged and perhaps misleading genocide.6

The DK period can be divided into four phases. The first lasted from the capture of Phnom Penh until the beginning of 1976 when DK formally came into existence, a constitution was proclaimed, and a new wave of migration was set in motion from the center and southwest, which were heavily populated but relatively unproductive, to the rich rice-growing areas in the northwest. The southwest had been liberated early and contained many revolutionary bases. It was crowded with refugees from Phnom Penh. Most of the northwest on the other hand had remained under republican control until April 1975. The regime counted on this area to lead the way in expanding Cambodia’s rice production, and the new people were the instruments chosen to achieve this goal. The fact that they were socially unredeemable was seen as an advantage because their deaths made no difference to the regime. In a chilling adage recalled by many survivors, they were often told, “Keeping you is no profit; losing you is no loss.”7

During this period, Phnom Penh radio enjoined its listeners via anonymous speakers and revolutionary songs to “build and defend” Cambodia against unnamed enemies (khmang) and traitors (kbot cheat) outside and within the country in patterns reminiscent of Maoist China. In view of the regime’s collapse in 1979, there was a poignant optimism built into these pronouncements, but in the early stages of the revolution many Cambodians seem to have believed that it would succeed. Moreover, from the perspective of the party’s leaders, genuine or imagined enemies had not yet surfaced.

DK’s second phase lasted until the end of September 1976 and marked the apogee of the regime, although conditions in most of the countryside deteriorated as the year progressed. It is uncertain why the leaders of the CPK waited so long to come into the open. They had managed to control the population without identifying themselves for nearly a year and a half. Perhaps this anonymity made them feel secure. China’s continuing patronage of Sihanouk might also have been a factor in the CPK’s postponing of its outright assumption of power. When the Chinese prime minister, Zhou Enlai, who was Prince Sihanouk’s most important patron, died in January 1976, the leaders of the CPK were ready to brush the prince aside and to force him to retire as chief of state. A confidential party document of March 1976 stated that “Sihanouk has run out of breath. He cannot go forward. Therefore we have decided to retire him.”8 Sihanouk resigned three days later. In reports broadcast over Phnom Penh radio probably for foreign consumption, he was offered a pension that was never paid and a monument in his honor that was never erected. By April 1976 he was living under guard in a villa on the grounds of the royal palace with his wife and their son, Sihamoni, who became king of Cambodia when Sihanouk retired in 2004. The prince stayed there, in relative comfort but in fear of his life, until he was sent by DK on a diplomatic mission to the UN in January 1979. The March 1976 DK document also noted that the new government “must be purely a party organization” and stated that “Comrade Pol,” a pseudonym for Saloth Sar who was not otherwise identified, would be prime minister.

The constitution of Democratic Kampuchea, promulgated in January 1976, guaranteed no human rights, defined few organs of government and, in effect, abolished private property, organized religion, and family-oriented agricultural production. The document acknowledged no foreign models, denied any foreign alliances or assistance, and said nothing about the CPK or Marxist-Leninist ideas. Instead, it made the revolution sound like a uniquely Cambodian affair with no connection to the outside world.9

When National Assembly elections were held in March, the CPK’s candidates were voted in unopposed. They included members of the CPK Central Committee, elected as peasants, rubber workers, and so on, as well as others harder to identify. Pol Pot, not otherwise identified, represented “rubber workers in the eastern zone.” The candidates had no territorial constituencies, being seen instead as representatives of certain classes of Khmer. New people were not nominated or eligible to vote, and it seems that in much of the country no elections ever took place. The assembly met only once, to approve the constitution, and never played a significant role in DK. Like the elections themselves, the assembly seems to have been formed to placate foreign opinion.

The people who achieved a prominent place in the new government were a mixture of intellectuals who had studied in France, including Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Sary’s wife, Ieng Thirith, Hu Nim, Khieu Samphan, Thiounn Thioenn and Son Sen; older members of the Indochinese Communist Party like Nuon Chea, Nhek Ros, Chou Chet, Non Suon, Ta Mok, and Sao Phim; and younger militants who had never left Cambodia, such as Von Vet, Khek Pen, and Chhim Samauk. Those in charge of the zones did not include any ex-students from France; they were concentrated in the newly established ministries of Phnom Penh.

THE FOUR-YEAR PLAN

Over the next few months, Pol Pot and his colleagues drafted a four-year economic plan “to build socialism in all fields.” The plan was to go into effect in September 1976, but it was never formally launched. It called for the collectivization of all Cambodian property and proposed ever-increasing levels of rice production throughout the country, with the aim of achieving an average national yield of three metric tons per hectare (1.4 tons per acre). The prerevolutionary national average, harvested under less stringent conditions and with monetary incentives, had been less than a ton per hectare, one of the lowest yields in Southeast Asia. The goal of tripling the average was to be achieved by extensive irrigation, double and triple cropping, longer working hours, and the release of revolutionary fervor supposedly derived from the people’s liberation from exploitation and individual concerns. The plan was hastily written. No effort was made to see if its proposals were appropriate to soil and water conditions in particular areas or if the infrastructure with which to achieve its goals was in place. Instead, the plan called for an “all out, storming offensive” by everyone throughout the country. Some writers have drawn parallels between the CPK’s program and the so-called war communism of the Soviet Union in the early 1920s; others compare DK’s policies to those known as the Great Leap Forward in China in the 1950s. No material incentives were offered the Cambodian people in the plan except the bizarre promise that everyone would enjoy dessert on a daily basis—by 1980! Cambodia’s newfound independence, the empowerment of the poor, and the end of exploitation were thought to be sufficient incentives and rewards.10

Under the plan, crops such as cotton, jute, rubber, coconuts, sugar, and kapok were also to be cultivated for export. With the money earned from exports, light industry was to be established and, eventually, heavy industry as well. Plans for the latter were particularly Utopian, for they were dependent on raw materials like iron, steel, and petroleum, which did not exist in DK. Cambodia’s extensive offshore petroleum deposits were not discovered until the 1990s.

In explaining the plan to high-ranking members of the party, an unnamed spokesman, presumably Pol Pot, stated that it could be accomplished swiftly. The DK revolution, after all, was “a new experience, and an important one for the whole world, because we don’t perform like others. We leap [directly to] a socialist revolution, and swiftly build socialism. We don’t need a long period of time for transformation.”11

The plan said nothing about leisure, religion, formal education, or family life. Although it was deemed crucial to “abolish illiteracy among the population,” nothing was said about what people would be given or allowed to read. Some primary schools existed in base areas by 1976, but education was not extended to new people or their children until 1977 or 1978. Education above the primary level did not exist before 1978, when a belated attempt was made to establish a technical high school in Phnom Penh. In part, DK officials were making a virtue of necessity, since most men and women known to be experienced schoolteachers and hostile to the CPK were suspected of treasonous intentions and were often killed as class enemies. Former teachers who were members of the party, like Pol Pot and Ieng Sary, now had more rewarding tasks to perform.

Most Cambodians under DK had to work ten to twelve hours a day, twelve months a year to accomplish the objectives of the plan. Many of those who were unaccustomed to physical labor soon died of malnutrition and overwork, but even those who had been farmers in prerevolutionary times found themselves working longer and harder than they had before 1975, with no material rewards, limited access to their spouses and children, and very little free time. By early 1976, food was already scarce, since the surpluses from the first harvests had been gathered up to feed the army, to be stored, or to be exported. The situation deteriorated in 1977 and 1978 when much of the country was stricken with famine. Many survivors recall months of eating rice gruel without much else. One of them, now living in Australia, has said, “We looked like the Africans you see on television. Our legs were like sticks; we could barely walk.”12

A similar famine had swept through China in the early 1960s in the wake of the Great Leap Forward. In Cambodia, news of the famine was slow to reach the leaders in Phnom Penh; when it did, starvation was seen as evidence of mismanagement and treachery by those cadres charged with distribution of food. These people, many of them loyal members of the CPK, were soon arrested, interrogated, and put to death. The DK’s leaders seem to have believed that the forces they had mobilized to defeat the Americans—two weeks earlier than a similar victory had taken place in Vietnam—were sufficient for any task set by the “clear-sighted” CPK.13

During this second stage of the DK era, inexperienced cadres, in order to meet the targets imposed from the center, placed what were often unbearable pressures on the April 17 people and everyone else under their command. One way of achieving surpluses was to reduce the amount of rice used for seed and what had been set aside to feed the people. Rations were sufficient for survival, and in several parts of the country, people had enough to eat for most of 1976. In much of the northwest, however, rations diminished as the center’s Utopian priorities came into force. Several hundred thousand more “new people” had been brought into the area in early 1976, and many of them were set to work hacking clearings out of the jungle. No Western-style medicines were available, and thousands soon died from malaria, overwork, and malnutrition.

A CRISIS IN THE PARTY

In early September 1976, Mao Zedong died shortly before the CPK was to celebrate its twenty-fifth anniversary. Pol Pot used his comments on Mao’s death to state publicly for the first time that Cambodia was being governed in accordance with Marxist-Leninist ideas. He stopped short of identifying angkar padevat as the CPK. It seems likely that the CPK had hoped to use its anniversary on September 30 to announce its existence to the world and to launch its Four-Year Plan. As the month wore on, however, a split developed inside the CPK between those who favored the 1951 date for the foundation of the party and those who preferred 1960, when a special congress had convened in Phnom Penh and had named Pol Pot and Ieng Sary, among others, to the party’s Central Committee. To those who preferred the 1960 date, the earlier one was suggestive of Vietnamese domination of the party. They viewed those who favored 1951 as people whose primary loyalties were to Vietnam. What Pol Pot later described as the putting down of a potential coup d’état against his rule was more likely a preemptive purge of several party members whose loyalties to the party (or to Vietnam) seemed to be greater than their loyalties to Pol Pot.14

Two prominent members of the CPK, Keo Meas and Non Suon, who both had ties to the Vietnamese-dominated phase of the party’s history were arrested and accused of treason. Their confessions assert that they supported a 1951 founding date for the CPK.15

Overall, several thousand typed and handwritten confessions have survived from the DK interrogation center in the Phnom Penh suburb of Tuol Sleng, known in the DK period by its code name S-21. At least fourteen thousand men and women were questioned, tortured, and executed at the facility between the end of 1975 and the first few days of 1979, and over four thousand of their dossiers survive. Some of these run to hundreds of pages. The confessions are invaluable for historians, but it is impossible to tell from these documents alone whether or not a genuine conspiracy to dethrone Pol Pot and his associates had gathered momentum by September 1976. Like Sihanouk and Lon Nol, Pol Pot considered disagreements over policy to be tantamount to treason, and arguments over the party’s founding date suggested to him that certain people wanted him removed from power.16

At the end of the month, barely four days before the anniversary of the party was to be celebrated, Pol Pot resigned as prime minister “for reasons of health” and was replaced by the second-ranking man in the CPK, Nuon Chea. Pol Pot’s health had often broken down in the preceding year and a half, but he probably announced his resignation at this point to throw his enemies off balance and to draw others into the open. The resignation, in fact, may never have actually taken place. By mid-October, in any case, he was back in office. In November, after the arrest of the Gang of Four, Pol Pot and five of his colleagues traveled secretly to China to reassure themselves of continuing Chinese support. By 1978 this included two Chinese engineering regiments engaged in building a military airfield near Kompong Chhnang. It is likely that this ongoing military help was agreed upon at this time.17

There was still no announcement of the party’s existence, however, as its leaders had decided to keep the matter secret for the time being, to postpone a formal announcement of the Four-Year Plan and to intensify the search for enemies inside the party. In the meantime, S-21 expanded its operations. Only two hundred prisoners entered the facility in 1975, but more than ten times that many (2,250) were brought there in 1976, and more than two-thirds of them were imprisoned between September and November, covering the period of unease in the CPK discussed above. Another five thousand prisoners were taken there in 1977, and approximately the same number were imprisoned in 1978. Factory workers in Phnom Penh, who knew about the center’s existence but not about what went on inside its barbed-wire walls, called it a“place of entering, no leaving” (konlanh choul ot cenh). Only a dozen of the prisoners taken there for interrogation avoided being put to death.18

In December 1976, as the purges intensified, Pol Pot presided over a “study session” restricted to high-ranking members of the party that was called to examine the progress of the Cambodian revolution. The document that has survived from this meeting, a speech by Pol Pot, is darker and more pessimistic than those produced earlier in the year. In a vivid passage, Pol Pot spoke of a “sickness in the party” that had developed during 1976:

We cannot locate it precisely. The illness must emerge to be examined. Because the heat of [previous stages of the revolution] was insufficient at the level of people’s struggle and class struggle . . . we searched for the microbes within the party without success. They are buried. As our socialist revolution advances, however, seeping more strongly into every corner of the party, the army and among the people, we can locate the evil microbes. . . . Those who defend us must be truly adept. They should have practice in observing. They must observe everything, but not so that those being observed are aware of it.19

Who were the observers and who were the observed? People opposed to the revolution were moving targets depending on the evolving policies and priorities of the party’s leadership. At different stages of DK’s short history, the “evil microbes” were those with middle-class backgrounds or soldiers who had fought for Lon Nol, those who had joined the Communist movement when it was guided by Vietnam, or those who had been exposed to foreign countries. In 1977, attention shifted to the northern and northwestern zones where famines had occurred, and by 1978 victims included high-ranking members of the party, military commanders, and officials associated with the eastern zone. To be suspected, a person had only to be mentioned in the confessions of three other people. Those accused would name the people they knew, and so on. Hundreds, probably thousands of those who were taken to S-21 were completely innocent of the charges brought against them, but everyone who was interrogated was considered guilty, and nearly all those who were interrogated were killed. News of people’s disappearances was used to keep their colleagues in the party in line, but the deaths themselves and the existence of the prison were not made public. The regime never expressed regret for anyone it had executed by mistake. For Pol Pot and his colleagues, too much hung in the balance for them to hesitate in attacking enemies of the party: the success of the revolution, the execution of policy, and the survival of the leaders themselves. At the end of his December 1976 speech, Pol Pot remarked that such enemies “have been entering the party continuously. . . . They remain—perhaps only one person, or two people. They remain.”20

The effect of brutal, ambiguous threats like these on the people listening to them is impossible to gauge. Within a year many of these men and women had been arrested, interrogated, tortured, and put to death at S-21. In most cases, they were forced to admit that they had joined the “CIA” (a blanket term for counterrevolutionary activity) early in their careers. Others claimed to have worked for Soviet or Vietnamese intelligence agencies. It is unclear whether Pol Pot and the cadres at S-21 who forced people to make these confessions believed in these conspiracies or merely in the efficacy of executing anyone who was suspected by those in power.21

CONFLICT WITH VIETNAM

The third phase of the DK era, between the political crisis of September 1976 and a speech by Pol Pot twelve months later in which he announced the existence of the CPK, was marked by waves of purges and by a shift toward blaming Cambodia’s difficulties and counterrevolutionary activity to an increasing extent on Vietnam. Open conflict with Vietnam had been a possibility ever since April 1975, when Cambodian forces had attacked several Vietnamese-held islands in the Gulf of Thailand with the hope of making territorial gains in the final stages of the Vietnam War. The Cambodian forces had been driven back and differences between the two Communist regimes had more or less been papered over, but DK’s distrust of Vietnamese territorial intentions was very deep. So were Pol Pot’s suspicions of the Vietnamese Communist Party, whose leaders had been patronizing toward their Cambodian counterparts for many years and had allowed Cambodia’s armed struggle to flourish only in the shadow of Vietnam’s. Pol Pot’s suspicions deepened in July 1977 when Vietnam signed a treaty of cooperation with Laos, a move that he interpreted as part of Vietnam’s plan to encircle Cambodia and to reconstitute and control what had once been French Indochina.22

Realizing the relative strengths of the two countries, however, Pol Pot tried at first to maintain correct relations and was unwilling to expand DK’s armed forces to defend eastern Cambodia against possible Vietnamese incursions. The Vietnamese, recovering from almost thirty years of fighting, were also cautious. In 1975–76, however, their attempts to open negotiations about the frontier were rebuffed by the Cambodians, who demanded that the Vietnamese honor the verbal agreements they had reached with Sihanouk in the 1960s. Cambodians claimed parts of the Gulf of Thailand, where they hoped to profit from partially explored but unexploited offshore oil deposits, but these claims were rejected by the Vietnamese, who had similar hopes. Skirmishes along the border between heavily armed, poorly disciplined troops in 1976 led Vietnamese and Cambodian leaders to doubt each other’s sincerity. The Cambodian raids were much more brutal, but the evidence for centralized control or approval for attacks on either side before the middle of 1977 is contradictory.23

The situation was complicated further by the fact that Pol Pot and his colleagues believed the Cambodian minorities in southern Vietnam were ready to overthrow Vietnamese rule; they wanted to attach these minorities to DK. Sihanouk and Lon Nol had also dreamt of a greater Cambodia. In fact, whatever the views of the Khmer in Vietnam might have been, they were insufficiently armed, motivated, and organized to revolt. When no uprising occurred, Pol Pot suspected treachery on the part of the agents he had dispatched to foment it. His troops were also merciless; on their cross-border raids that began in April 1977, they encountered and massacred hapless Khmer who had unwittingly failed to follow his scenario.

As so often in modern Cambodian history, what Cambodians interpreted as an internal affair or a quarrel between neighbors had unforeseen international repercussions. For several months after the death of Mao Zedong and the arrest of his radical subordinates known as the Gang of Four, the Chinese regime was in disarray. Although the four radicals were soon arrested, the new ruler, Hua Guofeng, tried to maintain Mao’s momentum by opposing the Soviet Union, praising Mao’s ideas and supporting third world revolutions like DK’s. Many Chinese officials, including Hua’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, perceived Vietnam as a pro-Soviet threat along their southern border—much as the United States at the time saw Cuba. For the Chinese, Cambodia was a convenient and conveniently radical ally. By early 1977, large quantities of arms, ammunition, and military equipment were coming into DK from China. Ironically, the Chinese were asking DK to play a role that mirrored the one played by the regime DK had overthrown, when the Khmer Republic had been “groomed” to serve the interests of the United States.24

This phase of the DK era ended in late September 1977 when Pol Pot, in a five-hour speech recorded for Phnom Penh radio, announced the existence of the CPK on the occasion of the seventeenth anniversary of its foundation.25 The speech failed to explain why the party’s existence had been kept a secret for so long, and the announcement may have responded to pressure from China in exchange for that country’s continuing military assistance. In any case, the day after the speech was broadcast Pol Pot flew to Beijing where he was feted publicly by Hua Guofeng, whom he had met in secret a year before. The Chinese offered extensive help to DK in its confrontation with Vietnam. More realistic than DK’s leaders, they did not support a full-scale war, knowing that Cambodia would lose, until they were pushed by Pol Pot and Vietnamese intransigence toward that position in 1978.26

Pol Pot’s long speech contained some veiled warnings to Vietnam, but its main intention was to review the long trajectory of Cambodian history, culminating in the triumph of the CPK. The format was chronological, divided into a discussion of events before 1960, between 1960 and 1975, and developments in DK itself. The 1960 congress, he asserted, marked the establishment of a “correct line” for the CPK, but since armed struggle was postponed for eight more years and the party’s leaders had to flee Phnom Penh in 1963, he found few benefits to mention that flowed from the party’s line in terms of revolutionary practice. Benefits flowed after the anti-Sihanouk coup, to be sure, but Pol Pot failed to mention the most significant of them, Vietnamese military assistance to the Khmer Rouge. Similarly, Sihanouk himself was never mentioned.

In closing, Pol Pot noted that “with complete confidence, we rely on the powerful revolutionary spirit, experience, and creative ingenuity of our people,” failing also to mention Chinese military aid. Optimistically, he predicted that Cambodia would soon have twenty million people (“Our aim is to increase the population as quickly as possible”) and claimed that the average food intake had reached over three hundred kilograms (660 pounds) of rice per person per year. Many refugees later took issue with the latter statement, pointing out that by the middle of 1977 in much of the country and for the first time in Cambodian history, rice had virtually disappeared from the diet.

It is likely that Pol Pot had been encouraged to make the speech and to bring the CPK into the open by his Chinese allies and that, because of the importance of that alliance, he was happy to oblige.

In late September 1977 Pol Pot embarked on a state visit to China. At the Beijing airport, the DK delegation was met by China’s premier, Hua Guofeng, and Deng Xiaoping, who was to replace Hua in 1978. The visit probably marked the high point (for Pol Pot at least) of the DK regime. The warmth of the welcome that the Cambodians received probably convinced him that the Chinese would support DK if and when hostilities broke out between Cambodia and Vietnam. In fact, while the Chinese encouraged DK’s hostility toward Vietnam, they also hoped for a peaceful solution.27

DK CLOSES DOWN

Vietnam saw the DK-Beijing alliance that was strengthened during Pol Pot’s visit to China as a provocation, and in mid-December 1977 Vietnam mounted a military offensive against Cambodia. Fourteen divisions were involved, and Vietnamese troops penetrated up to thirty-two kilometers (twenty miles) into Cambodia in some areas. In the first week of 1978, after DK had broken off diplomatic relations with Vietnam, most of the Vietnamese troops went home, taking along thousands of Cambodian villagers as hostages. The Vietnamese soon began grooming some of these hostages as a government in exile; others were given military training. One of the exiles, a DK regimental commander named Hun Sen, who had fled Cambodia in 1977, emerged as the premier of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) in 1985. Aside from the UN interregnum in 1992–93, he has remained in command of Cambodian politics ever since.

Pol Pot’s response to the Vietnamese withdrawal was to claim a “total victory,” while secretly purging military officers and CPK cadres in the eastern zone where the Vietnamese penetration had been the deepest. These men and women were said to have Cambodian bodies and Vietnamese minds. Several hundred of them were executed at Tuol Sleng; hundreds of others, on the spot.28 In the confusion many DK soldiers from the eastern zone sought refuge in Vietnam. One of them, Heng Samrin, later became the chief of state of the PRK and a revered, inconsequential figure in subsequent regimes. In addition, thousands of people in the east were forcibly transferred toward the west in early 1978. Local troops in the east were massacred and replaced by troops from the southwest. The man in charge of the eastern zone, an ICP veteran named Sao Phim, committed suicide in June 1978 when summoned to Phnom Penh for consultation. The massacres in the east continued for several months.29

In 1978 the DK regime tried to open itself to the outside world and to improve its image with the Cambodian people. Gestures included a general amnesty offered to the population and the establishment of a technical high school in Phnom Penh. The regime welcomed visits from sympathetic journalists and foreign radicals and inaugurated diplomatic relations with non-Communist countries such as Burma and Malaysia

These actions had mixed results. For example, a Yugoslavian television crew visited DK in 1978, and the footage broadcast later in the year gave the outside world its first glimpse of life there and of Pol Pot. One of the cameramen later remarked that the only person the crew had seen smiling in Cambodia was Pol Pot. Other visitors who sympathized with DK praised everything they saw. They were taken to see places the regime was proud of, and what they saw fit their preconceptions.

Most survivors of the regime, however, remember 1978 as the harshest year of DK, when communal dining halls were introduced in many areas and rations fell below the starvation levels of 1977.

By this time also, Vietnamese attempts to reopen negotiations with DK had failed. Nearly a hundred thousand Vietnamese troops were massed along the Cambodian border by April 1978, just before Pol Pot’s suppression of enemies in the eastern zone. Vietnam also signed a twenty-five-year treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union to balance the threat from China and in early December announced that a Kampuchean Front for National Salvation had been set up in “liberated Cambodian territory” to overthrow DK. The front included several leaders of later Khmer politics, such as Heng Samrin, Chea Sim, and Hun Sen.30

Vietnam and DK now embarked on a long and costly struggle that played into the hands of larger powers. These powers, in turn, were not prepared to take risks. There is evidence, for example, that Pol Pot requested that the Chinese provide volunteers but that the request was turned down. DK would have to face the Vietnamese (and serve Chinese interests) on its own. The parallels between the last days of DK and the last days of Lon Nol’s regime in 1975 are striking, and ironic.

In December 1978 two American journalists and a Scottish Marxist academic, Malcolm Caldwell, visited Cambodia. The journalists, Elizabeth Becker and Richard Dudman, had worked in Cambodia in the early 1970s, and they were the first nonsocialist writers to visit DK.

Recalling her visit several years later, Becker wrote:

The Phnom Penh I first glimpsed had the precise beauty of a mausoleum. . . . There was no litter on the streets, no trash, no dirt. But then there were no people either, no bicycles or buses and very few automobiles.31

Caldwell, who had written sympathetically about the regime, was invited to Cambodia as a friend, but Becker and Dudman were thought by DK officials to be working for the CIA, and the movements of all three were closely monitored. On their last night in the country, December 22, Caldwell was killed in his hotel room by unknown assailants perhaps connected with an anti–Pol Pot faction eager to destabilize the regime.

On Christmas Day 1978, Vietnamese forces numbering over one hundred thousand attacked DK on several fronts. Because DK forces were crowded into the eastern and southwestern zones, Vietnamese attacks in the northeast encountered little resistance, and by the end of the year several major roads to Phnom Penh were in Vietnamese hands. At this point the Vietnamese altered their strategy, which had been to occupy the eastern half of the country, and decided to capture the capital itself.

The city, by then containing perhaps fifty thousand bureaucrats, soldiers, and factory workers, was abandoned on January 7, 1979. Up to the last, DK officials had confidently claimed victory. Pol Pot, like the U.S. ambassador in 1975, escaped at the last moment in a jeep; other high officials and foreign diplomats left by train. They were followed later, on foot, by the half-starved, poorly equipped remnants of their armed forces.32

It was a humiliating end for the DK leaders and for their Utopian vision of Cambodia. The revolutionary organization never expressed regret for the appalling loss of life that had occurred since “liberation” in 1975. Even after DK’s demise, well into the 1990s, tens of thousands of Khmer, particularly young people, were still prepared to give their lives to the first organization that had given them power and self-respect. Some of these people formed the backbone of the Khmer Rouge guerrilla army in the 1980s. Moreover, once the purges had burnt themselves out, the leaders of the CPK (despite or perhaps because of the party’s official dissolution in 1981) remained in place and in command of the resistance throughout the 1980s and 1990s.33

Nearly everyone else welcomed the Vietnamese invasion and accepted the government that was swiftly put in place by the invaders as preferable to what had gone before. The new government called itself the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) and was staffed at its upper levels by former CPK members who had defected to Vietnam in 1977–78, as well as by some Khmer who had lived in Vietnam throughout the DK period. Most Cambodians rejoiced at the disappearance of a-Pot (“the contemptible Pot”), as they now called the deposed prime minister. For nearly everyone the DK era had been one of unmitigated suffering, violence, and confusion. With luck, in exile, or in the PRK, most Cambodians now thought they could resume their prerevolutionary lives, which DK had held in such contempt.34