In the autumn of 1927, Guy Burgess returned to Eton – Nigel had started the previous autumn – after a gap of almost three years. Frank Dobbs was only too happy to have him back and obtained special leave for him to do so from the Provost and Fellows, writing, ‘I am most awfully sorry to hear of the way your career in the navy has been made impossible by your eyesight. I shall be delighted to have you back again.’1 With his intelligence and charm, Burgess’s return to Eton appeared to go well, but this constant changing and abandoning of friendships must have been difficult, and contributed to what would become a growing sense of being an outsider.

He was playing football for his house, running the quarter-mile, and was rowing. He had also joined the Eton College Officer Training Corps, a popular choice though not compulsory, which took place several times a week with drill and field days and an annual camp, usually on Salisbury Plain; Burgess would remain in the ECOTC until his penultimate term, rising to the rank of lance corporal.

At the end of his first term back he took his school certificate – a general exam taken by all pupils aged sixteen and requiring six passes. He was now a history specialist, studying for a history essay question, general paper, divinity, a translation paper – he did both French and Latin – and one on civics or economics.

An important mentor was to be a history teacher, Robert Birley, only eight years older than Burgess, and known as ‘Red Robert’ for his liberal opinions. Birley, an imposing six foot six tall, had arrived straight from a glittering career as a Brackenbury scholar at Balliol a few terms earlier, and was to prove an important influence on Burgess with their shared interest in literature and history. A school contemporary, Nigel Nicolson, remembered how everyone looked forward to his classes. He would say:

Today we are going to talk about one of the most extraordinary events in history – the Sicilian campaign – and would then describe the ships, the armour, the politics, the battle, the danger, the glory, all with such emotion and sense of fun (he adored speaking of war oddly enough) that we felt we were actually in Sicily in 420 BC, rowing in the galleys, slaving in the mines, speaking in the Assembly.2

Birley ran the Essay Society, where each member, who had to be invited to join, read an essay on a subject of their choice over cups of cocoa. Burgess was to give several talks on subjects ranging from Ruskin to Mr Creevey, an eighteenth-century politician best known for the Creevey Papers on the political and social life of the late Georgian era.

Another strong influence was the art master, Eric Powell, a talented watercolourist who had rowed for Cambridge and in the 1908 summer Olympics.3 Burgess had developed into an accomplished artist and received numerous art and drawing prizes throughout his Eton career. He had a keen interest in art and was a regular visitor to art galleries, being especially ‘bowled over’ by Cezanne’s ‘Black Marble Clock’ at the French Exhibition at Burlington House. His own drawings, though, were caricatures in the style of Daumier or the political caricatures of ‘Spy’. David Astor remembered him as forever drawing cartoons of masters and others in authority, and using that as a means of channelling his growing rebelliousness, a view confirmed by Michael Berry, and many of his pictures can be found in Eton’s ephemeral magazines, to which he continued to contribute even after he left Eton.4

Roland Pym, later a painter and book illustrator, who took extra studies in literature and art with Burgess, ‘didn’t like him, but can’t really say why. Bumptious and cocky?’ adding, ‘He would hold forth in front of the whole class. He must have been sensitive because he blushed easily.’5

Burgess continued his intellectual ascent of the school. In Lent 1928 he was first in the Remove and by July 1928 he was ranked twentieth of the First Hundred – boys who were the academic elite of the school.6 He was now a member of the Sixth Form with its special privileges of a butterfly tie and being able to walk on Sixth Form grass, though he claimed he took no pleasure in another perk – attending birchings.7

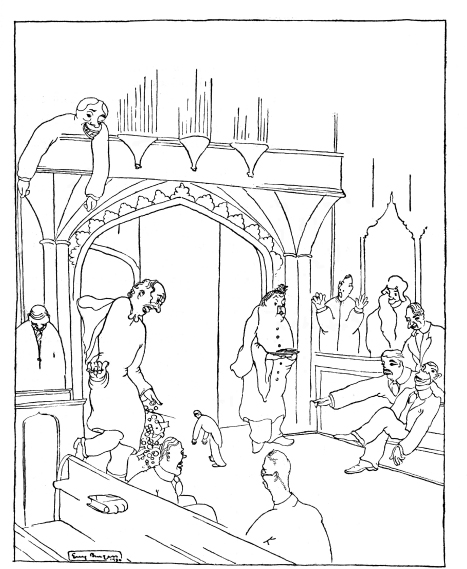

Burgess’s illustration in ‘A Mixed Grill’, 4 June 1930

In November 1928 he had an ‘honourable mention’ with the future philosopher A.J. Ayer in the Richards English Essay Prize and in April 1929 he was second in the school’s premier history prize, the Rosebery.8

At Christmas 1928, Robert Birley wrote to Burgess’s housemaster, Frank Dobbs:

At the moment his ideas are running away with him and he is finding in verbal quibbles and Chestertonian comparisons a rather unhealthy delight, but he is such a sane person, and so modest essentially, that I do not feel this very much matters. The great thing is that he really thinks for himself. It is refreshing to find one who is really well read and who can become enthusiastic or have something to say about most things from Vermeer to Meredith. He is also a lively and amusing person, generous, I think, and very good natured … He should do very well.9

After Malcolm’s death, the family had continued to live in West Meon, though they had briefly moved to the Old Barn at Chiddingfold at the beginning of his Eton career. Holidays tended to be spent in Hampshire, though there was some excitement at the beginning of April 1929 when Burgess, his brother, then known as Kingsley, and their mother sailed from Southampton, via Tangier, to escort a relation, a sugar refiner called John Bennett Crispin Burgess, to Indonesia, returning three weeks later with a stop at Colombo.10

It is not clear when Burgess realised he was homosexual or the extent of his sexual experiences at Eton. He later claimed to the Russians that he had become homosexual at Eton, where it was common and even masters were seducing boys, and a later screenplay, Influence, by Goronwy Rees, has him beaten for sexually assaulting a boy. Homosexuality was certainly prevalent – many Old Etonian memoirs for the period discuss it – and it seems unlikely that Burgess, with his good looks, would have gone unnoticed. Burgess later told a boyfriend that a scion of the aristocratic brewing family Guinness was totally infatuated with him. Outside the door of the younger boy’s tiny room in Dobbs’s house, he attached an advertising sign as proof of his devotion. It read: ‘Guinness is Good For You’.11

But the accounts of contemporaries suggest that, if he was homosexual, he was very discreet. Dick Beddington, one of Burgess’s closest friends at Eton, saw no indication of it, but felt he was a very private person who kept his life very compartmentalised. Michael Berry told Andrew Boyle that he thought Burgess had indulged in homosexuality,12 whilst Evan James suggested, ‘He may have done, but if he had been in any way notorious for this I should possibly have heard wind of it.’13

Lord Cawley, who was in his house, said, ‘Burgess always appeared to be an affable character and I never heard any rumour about his homosexuality.’14 Lord Hastings thought ‘he was probably homosexual but so were a great many boys (some twenty per cent in my tutor’s) who indulged in mild sexual practices (never oral for instance), but who subsequently grew up as perfectly normal adults’.15

Memories of him from his contemporaries vary. Many refer to his unpopularity, his sense of inferiority and being a loner, whilst others speak of his kindness and warmth. Diametrically opposing views of Burgess were to be a pattern that was to repeat itself throughout his double life. Lord Hastings wrote, ‘It is difficult to analyse a boy’s character if you are not in the same house, but I gather that Guy was lacking in self-confidence and trying to ingratiate himself with everybody, and that seldom leads to popularity!’16 Michael Legge remembered him as ‘an amusing man, totally unself-conscious and a strong personality’,17 whilst David Philips, another contemporary, thought him ‘a bit of a loner and a bit of a rebel. He was looked on as a bit left-wing and an outsider in his social and political views.’18

William Seymour, a neighbour in West Meon, liked Burgess and remembered a flamboyant figure who flouted his house colours, wrapped his scarf around his desk, and was keenly political.19 Another classmate, Mark Johnson, simply remembered him as ‘being kind and friendly to small boys’.20

Evelyn had taken her husband Malcolm’s death hard and remained a recluse for four years, but in late 1928 she met a retired army officer, John Bassett, and the following July they were married at St Martin-in-the-Fields church in Trafalgar Square. Guy and Nigel Burgess learnt the news of the forthcoming marriage not from their mother, but from their housemaster.21

Her new husband, John Bassett, was seven years older than Eve, and had retired as a lieutenant colonel in his early forties in 1920. The couple shared a love of racing, which extended in Bassett’s case to horse betting. When asked what his new stepfather did, Burgess would reply in a solemn voice, ‘I’m afraid he’s a professional gambler.’ Bassett was, in fact, rather more than that, and he’d had a distinguished military career. Commissioned into the Royal Berkshire Regiment in 1898, he had served in East Africa, the Sudan, where he had governed a province, Abyssinia, and in the Boer War, and later he worked alongside Lawrence of Arabia. For his services in the First World War he had earned a Légion d’Honneur, OBE, and DSO, which rather eclipsed Malcolm’s Order of the Nile 4th Class.

Burgess returned to Eton for his final year in September 1929 and was one of six boys chosen to give speeches on 5 October. He had picked a piece from H.G. Wells’, ‘Mr Polly’s reflections on the plump woman’, to which the Eton College Chronicle commented: ‘he brought out the climax well [but] his enunciation is too much slurred to allow him always to be audible’.22

Burgess had always read widely, but now his reading became increasingly politicised, with Arthur Morrison’s The Hole in the Wall and Tales of Mean Streets and Alexander Paterson’s Across the Bridge, with its exposure of conditions in London’s East End, being particularly influential. Burgess’s own political views were also being shaped by his history teacher Robert Birley’s concern for social justice. A visit by a dockers’ trade union organiser to the school, where he talked about inequalities between rich and poor, only helped to reinforce a growing interest in radical politics.23

He had joined the Political Society, which met on Wednesday evenings in the Vice Provost’s Library, hearing talks from Hilaire Belloc on ‘The Decay of Parliament in Central Europe’, G.K. Chesterton on ‘Democracy’ and Paul Gore-Booth, a Colleger, on ‘Russian Bolshevism’.24 In July 1929 he was elected to the committee, of which his friend Dick Beddington was secretary, though clearly something had happened by May 1930, when it ‘was decided that Mr Burgess should be deposed from the Committee’ and his appeal to be reinstated was rejected, suggesting some sort of disagreement. Burgess was later to claim that the election of the Labour government in 1929 ‘made some impression’ on him and he would argue ‘in favour of socialism with the son of an American millionaire’, Robert Grant.25

He was also active in the newly resurrected debating society, which met on Monday evenings. On 3 October 1929 they met to discuss whether the English public school system was a good idea or not, and on 10 October it was ‘Russia – Country of the Future?’ On 25 October, with police riot squads forced to deal with crowds on Wall Street, he attended a debate on ‘whether radical changes are needed at Eton in view of the rise of Socialism’. It was proposed by David Hedley and Burgess supported the motion, though it was lost with 38 for and 50 against.

According to Dick Beddington, the fair-haired six-foot Hedley was a brilliant student and with Burgess ‘undoubtedly the two most interesting chaps at Eton at the time’.26 Hedley was school captain, a 1st XI footballer, gregarious, amusing, popular, good-looking, Keeper of the Wall, winner of the Newcastle Prize, Editor of Eton College Chronicle, and a rower. He also had supposedly become one of Burgess’s sexual conquests.

By January 1930, Burgess was ranked second after Hedley in the Sixth Form, which comprised the top ten scholars and top ten Oppidans – Oppidans are the non-scholars at Eton – and that month he sat and won a history scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, with Hedley winning a scholarship in classics to King’s College, Cambridge.

According to Burgess’s own later account:

when he met the examiners later, they told him that they had never before given an open scholarship to anybody who knew so little as he did. Apparently they decided in his favour largely on the strength of one exceptionally promising paper in which, referring to the French Revolution, he expressed energetic disapproval of Castlereagh.27

Burgess, who so much wanted to belong, had achieved most of Eton’s Glittering Prizes. He had been awarded his house colours, was a highly regarded member of the 1st XI Football and probably the best swimmer in the school. He was also a member of the self-elected Library (the house prefects) in his house, where one blackball excluded, which suggests he wasn’t that unpopular, although as a member of Sixth Form he should have been captain of the house.28

However, one distinction still eluded him – membership of Pop, a self-elected elite of between twenty-four and twenty-eight boys, which conferred special privileges such as wearing coloured waistcoats, carrying umbrellas, and caning other non-Pop boys. Between September 1929 and May 1930, Burgess’s name was put forward unsuccessfully several times, sponsored by, amongst others, David Hedley and Michael Berry. There were good reasons for his failure. His house already had two members of Pop, the president of Pop, Robert Grant, an outstanding racquets player, and Tony Baerlein, who kept wicket for the Eton 1st XI for three years.29 Burgess was clever, but Pop tended to recognise sporting rather than academic achievement, and to prefer aristocrats rather than the sons of naval officers.

It didn’t surprise another Eton contemporary, Peter Calvocoressi: ‘I don’t think it was very strange that he never got into Pop. There were three kinds of Pop members: ex officio, good at games, an exceptionally “good chap”. He was none of those things!’30 As Berry was later to admit, ‘When it came to getting Guy in, I discovered to my surprise how unpopular he was. People just didn’t like him.’31

Pop notwithstanding, Burgess’s final days were ones of glory. He played a prominent role in the school’s 4th June celebrations, graced that year by the presence of the King who presented the Officer Training Corps with new colours. At speeches in the morning, dressed in breeches and black stockings, he read Southwell’s ‘Good Things’, though the Eton College Chronicle noted, ‘Only two of the prose passages suffered from being spoken too low. In the case of Burgess the trouble was, perhaps, rather a failure to enunciate clearly. A catalogue of “good things” is a difficult idea to manage. He expressed well, however, the minor key of his passage.’32 He played Sir Christopher Hatton in Sheridan’s The Critic and several of his cartoons were in The Mixed Grill, a magazine produced for the day. That evening he rowed in Monarch, the senior boat in the Procession of Boats made up of school celebrities, alongside Hedley, McGillycuddy, and Robert Grant.

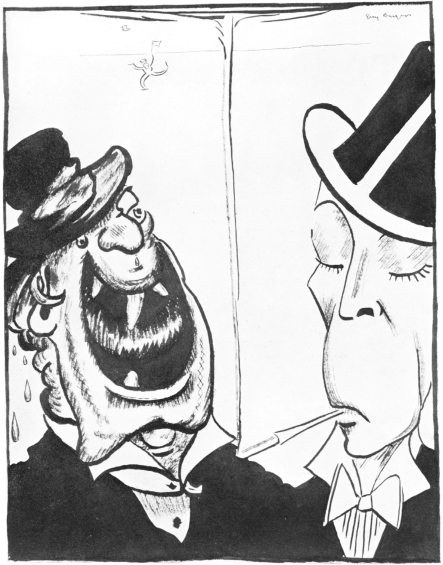

Guy Burgess’s cartoon in Eton ephemeral magazine ‘Motley’, 10 July 1931

A month later, his career at Eton came to an end. He had been awarded the Gladstone Memorial Scholarship based on the results of the final exams – £100 and a two-volume set of Morley’s life of Gladstone, signed by a member of the Gladstone family – and the Geoffrey Gunther Memorial Prize for design. His time at the school had been a success. Robert Birley was later to tell Andrew Boyle that Burgess:

had a gift for plunging to the root of any question and his essays were on occasion full of insights. He went through Eton without a blemish. V. gifted and affable, articulate, never in trouble. No hint of any fault or defect in character. Member of the Essay Society and a good one. He had a natural feel for history and did well at Eton.33

Burgess’s feelings about the school were complex. Steven Runciman, an Old Etonian who taught him at Cambridge, later claimed, ‘He enjoyed Eton without liking it. He used to laugh about it,’34 but many of Burgess’s contacts and much of his identity came from being an Old Etonian, and he retained a strong emotional attachment to the school. He would later say that though he disapproved ‘of the educational system of which Eton is a part’, as an Old Etonian, he had ‘an enduring love for Eton as a place, and an admiration for its liberal educational methods’. He continued to wear his OE tie – he proudly boasted of being ‘one of the few Old Etonians to wear an Old Etonian bow-tie throughout his life’ – and often returned to the school to see Dobbs and Birley, attend chapel services and, as he later recollected, ‘spend summer weekends in a punt moored by Luxmoore’s Garden’.35