After Hitler’s annexation of Austria, several overlapping irregular and clandestine organisations had been set up. One of them was Section D of SIS, created in April 1938 ‘to provide lines of communication for covert anti-Nazi propaganda in neutral countries and to direct and harness the efforts of the various anti-Nazi organisations then working in Europe’.1 Its role was to organise and equip resistance units, support anti-Nazi groups, sabotage, covert operations, and subversive propaganda. Indeed, it had already ‘organised secret propaganda during the Munich crisis’.2

Through David Footman, Burgess had obtained an introduction to its head, Major Laurence Grand. A Cambridge graduate, Grand was then thirty-nine, a Royal Engineers officer who had experience in irregular warfare in Russia, Iraq, Kurdistan and India. A tall, handsome man with a heavy dark moustache, always with a red carnation in his well-tailored suits, and a chain smoker, he was a man full of ideas and he quickly came up with plans for subversive operations, ranging from sabotage and labour unrest to propaganda.

Burgess had a vague brief over the next two years, which included acting as liaison between Section D, the Ministry of Information, and a ‘black ops’ propaganda organisation based at Electra House on the Thames embankment. It meant Burgess was, in his own words, ‘buzzing about doing a lot of things’ without anyone being sure who had authorised his schemes or what he was doing. It also meant he had access to highly confidential information about the preparations for war.3

His main focus, where his skills as a talks producer came in most useful, was the Joint Broadcasting Committee, set up a few months earlier by the Foreign Office, which recognised that a counteroffensive was needed against Hitler. As broadcasting directly into Germany was forbidden by the 1936 International Broadcasting Convention, a secret broadcasting organisation was required.4

MI6, working with Joseph Ball and Gerald Wellesley, later 7th Duke of Wellington, had already engineered the transmission of Chamberlain’s speeches on the Munich crisis over Radio Luxembourg. Broadcasting mainly popular music, this commercial operation was one of Europe’s most popular stations, and the British government had paid for the air time through the secret agency of the Travel and Industrial Association of Great Britain and the Hendon Travel Bureau. Now the operation was expanded, with a brief to spread positive information about Britain, its way of life and values.5

The JBC was very much a BBC operation. It was run by Hilda Matheson, who had been in MI5 during the First World War and was the BBC’s director of Talks and News between 1926 and 1932 – and incidentally was a former lover of Harold Nicolson’s wife – assisted by Isa Morley, the foreign director of the BBC from 1933 to 1937. Burgess was number three and represented Section D’s interests. In March 1939 Harold Nicolson joined the Board. The JBC’s overt programmes were sent free to neutral and friendly countries in the languages of those countries by telephone, on disc, or sometimes the scripts were sent to be produced locally. A strong focus was securing British propaganda broadcasts on the American networks.6

The covert side, where Burgess largely worked, produced programmes for distribution in enemy countries, working with Electra House. Burgess was responsible for a variety of programmes that were recorded on large shellac discs and then smuggled in the diplomatic bag or by agents into Sweden, Liechtenstein and Germany, and broadcast as if they were part of regular transmissions from the German stations themselves.

One of Burgess’s jobs was producing anti-Hitler propaganda broadcasts, using clandestine transmitters from radio stations in Luxembourg and Liechtenstein, which were then beamed into Germany. The work was similar to his work in the Talks Department – preparing scripts and producing the recordings, giving a picture of life in Britain. JBC staff were authorised to use BBC studios and the recording facilities of commercial firms such as J. Walter Thompson. They also had mobile recording units, which could be contained in a couple of suitcases and moved by car.

Though scripts were prepared by JBC staff, many were read by prominent exiles such as the writer Thomas Mann, or later by well-known actors such as Conrad Veidt, shortly to star in the film Casablanca. Amongst those Burgess persuaded to broadcast was J.D. Bernal on ‘The British Contribution to Science’ and President Benes, now an exile in Britain, who recorded a talk on 19 September 1939.7 Thanks to his international contacts, gained ironically through his work for the Comintern, Burgess quickly found sites for transmitters, and the radio stations began broadcasting in the spring of 1939.

Among his colleagues was the writer Elspeth Huxley, whose abiding memory ‘is of Guy Burgess going downstairs to lunch about 12.30 and staggering back quite drunk and reeking of brandy at about 3.30 or 4 p.m.’8 Another colleague was Moura Budberg, until MI5, who had kept her under surveillance since the 1920s, asked for her to be moved elsewhere. Budberg had an exotic past. She had been the lover of the former Russian prime minister Alexander Kerensky, Maxim Gorky and H.G. Wells, imprisoned in the Lubyanka during the First World War accused of spying for the British, and was probably correctly suspected of having being a Russian agent. She was to become a close friend of Burgess.9

Few of the JBC records have been released, but tantalising glimpses of Burgess’s work can be gleaned from Harold Nicolson’s diary. On 5 May he recorded that Burgess ‘wants us to get Geneva to broadcast foreign news from the L[eague] of N[ations] station regularly each hour’. On 13 June, ‘He tells me dreadful stories about his childhood and in the interval, we discuss foreign broadcasts.’ On 26 July, ‘Guy Burgess comes to see me. He is organising his wireless very well.’10

Section D used a series of front organisations, such as the news agency United Correspondents, which produced innocuous but anti-Nazi articles for circulation to newspapers around the world, and Burgess worked with writers such as the Swiss journalist Eugen Lennhof and the Austrian writer Berthe Zuckerkandl-Szeps.11

As war grew more likely, new organisations were created and Burgess was now transferred from Grand’s budget to the Ministry of Information and appointed as the JBC Liaison Officer with the Ministry of Information, which had taken on many of the responsibilities for wartime propaganda.12

In March 1939 Britain and France had agreed to guarantee Poland’s sovereignty and two weeks later the Soviet foreign minister had proposed a triple alliance against a German attack. Throughout the summer, British and French diplomats had been trying to agree terms with the Soviet Union. Burgess proved invaluable to the Russians, reporting to Moscow that the British Government remained distrustful of the Soviet Union and was continuing to talk to Germany.

In July, Burgess had contacted John Cairncross, who had moved from the Foreign Office to the Treasury, saying that he was working for a secret British agency and was in touch with some anti-Nazi German generals linked with an underground broadcasting network. He needed information for them on British intentions towards Poland, but for various bureaucratic and personal reasons was unable to obtain it from the Foreign Office. Could Cairncross perhaps talk to some of his former colleagues, by giving them lunch, and he offered him £20 for his expenses. Cairncross duly obtained the information and wrote up some notes adding ‘a personal description of my “sources” designed to enable the recipient of my notes to make some kind of assessment of their reliability’. He also signed a receipt for the expenses, as Burgess thought he might be able to claim the monies from his employers. It was to prove a fateful mistake for him.13

On 3 August 1939, Burgess reported to the Russians that the British chiefs of staff felt that ‘a war between Britain and Germany can easily be won’ and that therefore the government did not need to conclude a defensive pact with the Soviet Union. Such inside information only reinforced Stalin’s suspicion that the British and French governments were not seriously interested in a treaty and Russian interests might best be served by a pact with Germany.14 Two days later, Burgess had dinner with Major Grand, who had that day met members of the military mission to Russia to discuss some sort of Anglo-Soviet agreement to guarantee Poland’s sovereignty, and was shocked by Grand’s response that ‘they had no power to reach agreement, and indeed their instructions were to prolong the negotiations without reaching agreement’.15

Three weeks later, Burgess wrote that, ‘In Government departments and talks with those who saw the documents about the negotiations, the opinion is that we have never intended to conclude a serious military pact … with the Russians.’16 The consequences were momentous. On 23 August the Soviet Union and Germany signed a ten-year non-aggression pact, which included a secret protocol to divide Poland and the Baltic states between them. It was a seismic moment for British communists, who had placed their faith in the Soviet Union to stand up to Hitler, and undermined all they had been fighting against over the previous six years.

Burgess and Blunt were on a month’s holiday and in the south of France, en route to Italy, when news of the non-aggression pact broke. Burgess, according to Blunt, ‘got a telegram ordering him back to London from “D”, the organisation within MI6 for which he was working’, and immediately drove back from Antibes, left his treasured car at a Channel port to be shipped back later, and caught the night boat back.17

Anthony Blunt remembered:

During the day [Burgess] produced half-a-dozen justifications for [the Russo-German pact] of which the principal argument was the one which eventually turned out to be correct, namely that it was only a tactical manoeuvre to allow the Russians time to rearm, before the eventual and inevitable German attack. He also used an argument which he had frequently brought up during the previous months, that the British negotiations which had been going on for an Anglo-Russian pact were a bluff … Whether this was true or not I had and have no means of knowing, but Guy certainly believed it at the time – and no doubt passed on his opinion to his Russian contact.18

According to one of the Russian handlers:

The Group organised a meeting in London, with Philby present. They analysed the pact with precision, considering its articles one by one and gauging its probable consequences. The discussion was calm but uncompromising. After several hours of argument they concluded that the pact was no more than an episode in the march of revolution; that in the circumstances it might easily be justified; and that in any event it did not constitute sufficient pretext for a break with the Soviet Union.19

The next day Burgess appeared at Goronwy Rees’s flat in Ebury Street. ‘He was in a state of considerable excitement and exhaustion; but I thought I also noticed something about him which I had never seen before. He was frightened’, Rees later wrote. Burgess appeared accepting of the volte-face, claiming ‘that after Munich, the Soviet Union was perfectly justified in putting its own security first and indeed that if they had not done so they would have betrayed the interests of the working class, both in the Soviet Union and throughout the world’, but Rees noticed he was strained and apprehensive.20

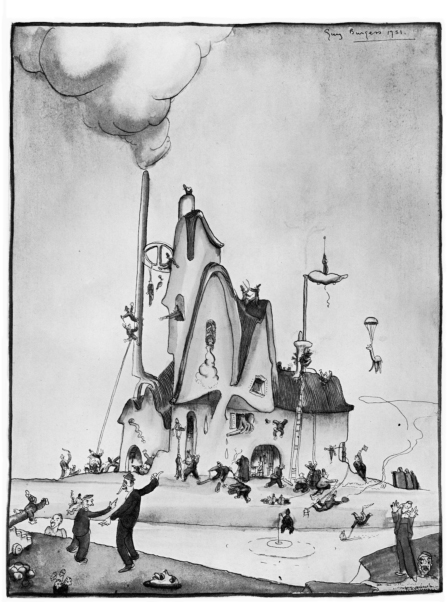

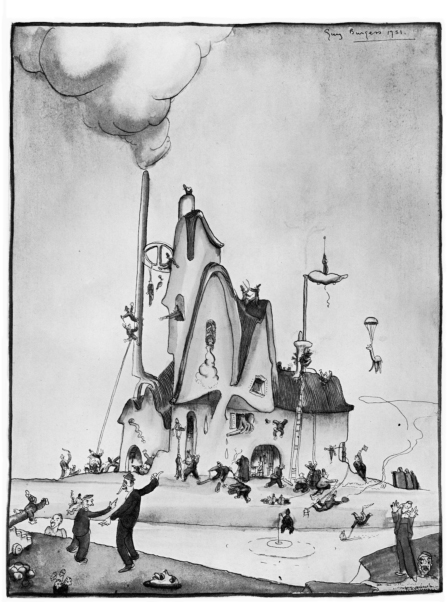

Burgess’s cartoon from the Eton ephemeral magazine ‘Motley’, 10 July 1931

Burgess asked him what he wanted to do and Rees replied, ‘“I never want to have anything to do with the Comintern for the rest of my life. Or with you, if you really are one of their agents.”

“The best thing to do would be to forget the whole thing,” he said. “And never mention it again … as if it had never happened.”

“I’ll never mention it,” I said. “I want to forget about it.”

“That’s splendid,” he said with obvious relief. “It’s exactly what I feel. Now let’s go and have a drink.”’21

Burgess, in order to ensure Rees wouldn’t betray him and Blunt, pretended to his friend that he, too, had become disillusioned by the Nazi-Soviet Pact and given up his illegal work for the Communist Party. Rees seemed to be reassured, but he was to prove to be a ticking bomb.