In April 1946 Christopher Warner, an Assistant Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, had drafted a memo, ‘The Soviet campaign against this country and our response to it’, arguing for the need to respond to the Soviet ideological ‘offensive’, which had taken the form of sponsorship of communist organisations in Western Europe and support for ‘nationalist’ and ‘anti-colonial’ movements. The Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, had agreed the need for a department which could seize the propaganda offensive from Russia, a desire strengthened by his experience at the United Nations in October 1947, where he had faced an onslaught of well-researched misinformation and disinformation from the Russians. Christopher Mayhew, the other Minister of State at the Foreign Office, who incidentally had gone to Russia with Anthony Blunt in 1935, was tasked with setting up a department to win the propaganda war against the Soviet Union.

The new organisation was approved at a Cabinet meeting on 8 January 1948, when it was decided ‘that a new line of foreign publicity should be adopted, designed to oppose the inroads of Communism by taking the offensive against it’.1

Established with £150,000, the new organisation was given the innocuous title of the Information Research Department and came into being at the end of February. Though only in part funded by the Secret Vote – how parliament funds MI5 and MI6 – from September 1948, it enjoyed close links from its inception with MI6. The department didn’t just deal in distributing propaganda through British embassies and media, but also supplied the Labour Party’s international department, whose secretary was Denis Healey, and trade unions. IRD collated information on the Soviets and communism in the Soviet Union, Europe and the Middle and Far East from the media and British representatives abroad, and then produced rebuttals, much like a political research department.

Its role was to brief ministers and delegates to international conferences, produce ‘Speaker’s Notes’, and place articles in the widest range of publications. In the first three months of the department’s existence, briefs were produced on such subjects as the real conditions in Soviet Russia and in the communist-dominated states of Eastern Europe, labour and trade unions in the Soviet Union, and communists and the freedom of the press.

Given his background in propaganda, it was natural that Burgess should work with the new department. Mayhew had approached Hector McNeil, saying he needed someone who ‘knew more about communism than the communists’. McNeil immediately recommended Burgess. ‘I think he wanted to get rid of him,’ Mayhew later remembered. ‘I think Guy Burgess also had a plan in mind. I interviewed Guy Burgess and, of course, on the subject of communist and anti-communist warfare he was brilliant. He knew more about it than I did. He had ideas that had never occurred to me. I immediately employed him.’2

The Information Research Department had three sections: Intelligence, Editorial and Reference. The Intelligence Section was responsible for collecting material from Whitehall departments, reports from missions and colonial posts, as well as press and broadcast monitoring. The Editorial Section prepared the output material and the Reference Section indexed and stored it. It was staffed not just by Foreign Office personnel, but also by wartime propagandists and journalists. There were separate desks for geographical areas, such as Eastern Europe, Africa, China, and Latin America, as well as sections on subjects such as economic affairs.

Burgess’s role in IRD is unclear. According to the Foreign Office official historian Gill Bennett ‘Burgess was never a member of IRD in any established sense … Burgess may have been involved in discussions about the creation of the department, and its early work, but I have seen no documentary evidence of any input from him. I have confirmed this with someone who knows a lot about IRD’.3

But he certainly played some role. A former member of IRD Hugh Lunghi, remembered how Burgess was always losing things and he was sacked because he was ‘lazy, careless, unpunctual and a slob’.4 In his memoirs, Mayhew wrote, ‘I threw him out. He was dirty, drunk and idle. I couldn’t sack him. He was Hector’s protege. I just disposed of him. I sent him back to the pool with a very bad report. Hector was a splendid fellow. He was very patriotic. He was a good man. An able man. But he was taken for a ride by Burgess.’5

Whatever his role, it is likely Burgess gave the Russians details of what he had learnt about the fledgling organisation. Certainly a Soviet bloc newspaper was carrying details of the new IRD by 4 April 1948.8 What is not clear is exactly what Burgess was able to reveal as, according to a leading authority on the subject, ‘Nothing has been found in the IRD files about Burgess or his position in the Department and other early recruits have no recollection of reading any of Burgess’s work … specific directives regarding propaganda in different regions were not drafted until the summer of 1948, when Burgess had almost certainly left the IRD.’6

Burgess was back working for McNeil by the middle of March 1948. Indeed, so trusted was he that McNeil asked him on 15 March to report on anyone who might be suspicious on the staff. Two days later, he accompanied McNeil to Brussels for the signing of the Treaty of Brussels that set up the Western Union Defence Organisation, which was eventually to evolve into the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). There he took the minutes at a secret meeting between McNeil and the Belgian foreign minister, Henri Spaak, with only the British ambassador to Brussels, Sir George Rendell, present. Aware of the heightened security, Burgess was cautious and simply confined himself to passing on the text of the Brussels agreement and the minutes he had so dutifully taken.7

One of Burgess’s responsibilities was dealing with French claims arising from the war. Ronald Grierson, then in the Paris embassy, remembers liaising with Burgess over the military awards to members of the French Resistance, and thought him ‘unstuffy and like an eccentric academic’.8 Rosemary Say, who had escaped as a young au-pair from German-Occupied France in 1942 and then found herself presented with a bill by the Foreign Office after the war, for monies she had been advanced by consular officials to live on, remembered, ‘I was still bitterly resentful that I had to pay the full cost of my escape and that no recognition had been given of what I had done or had been through. I was by now working as a secretary to Tom Driberg, the Labour MP. In that capacity, I had come into contact on several occasions with a very helpful official at the Foreign Office – a Mr Guy Burgess.’ At the end of November 1947, she wrote to Burgess asking if her debt could be cancelled and three weeks later, writing from 8 Carlton House Terrace, he replied that he had made enquiries and it had been agreed.9

There were also various odd jobs. McNeil chaired the Refugees Defence Committee, which looked at the question of resettling the millions of people displaced by the war. Michael Alexander, only just released as a POW from Colditz, worked with him on resettlement and was noticeably struck by Burgess’s ruthless views on sending refugees back to their home country.10

Another role was as McNeil’s speech writer. The journalist Henry Brandon, who was a close friend of McNeil’s, later claimed, ‘McNeil kept him on in spite of his often irascible behaviour and drinking habits because, he said, Burgess had all the important Stalin and Lenin quotes at his fingertips.’11 The relationship between Brandon and Burgess was less good. ‘He considered me too prejudiced against the Soviet Union’, Brandon later wrote. ‘Once at a small dinner in McNeil’s flat in London, Burgess attacked me personally in such an abusive manner that next day the Minister of State sent me a note of apology; none came from Burgess.’12

In spite of the difficulties of taking out documents, a Russian assessment of the information Burgess provided for the six months to 15 May 1948 shows that he had taken out over two thousand documents, of which almost seven hundred had been forwarded to Moscow where they were distributed to, amongst others, Stalin, the foreign minister Molotov, the Foreign Ministry, Russian Army intelligence, and various directorates of Soviet intelligence. So pleased were the Russians that Burgess was paid £200.13 During the summer, he was much involved in the Berlin Crisis, working closely with the German political section in Northern Department and IRD. There are numerous minutes giving background to the crisis and it’s clear Burgess saw reports from the Berlin Intelligence Staff and the Military Government Liaison Section.14

A good example of how stolen documents helped the Russians is a memo Burgess wrote on 5 July 1948 to McNeil, on the agreements governing written rights of access to Berlin.15 Why was this important? The previous month, Britain, France and America had given up their zones to create West Germany, with Berlin remaining a divided city reached through the Russian sector. The Russian response was to cut off all rail and road links, in an attempt to force the city to become part of the Russian sector. The knowledge that the British had looked recently at the agreements about access to the city would have given the Russians a clear idea of the policy and mindset of the British.

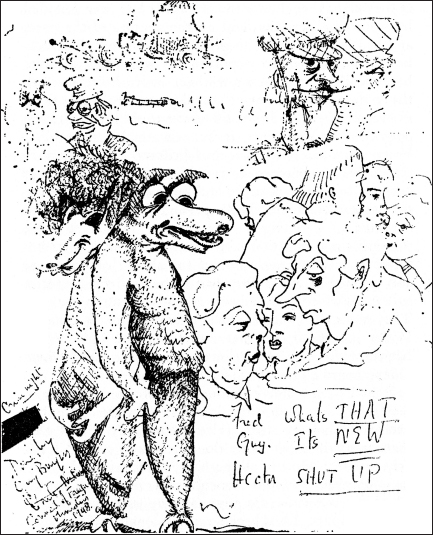

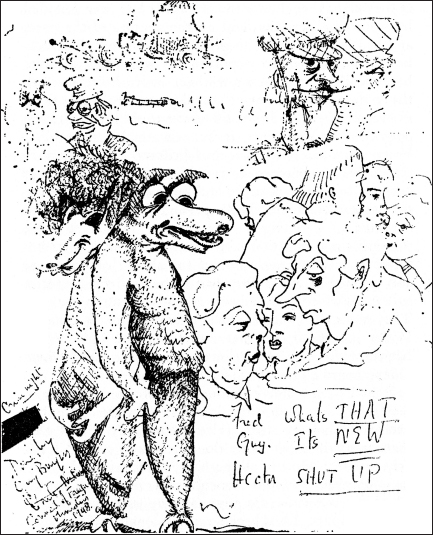

The Berlin Blockade, which was to last until the following May and only be broken by an airlift of supplies to the beleaguered city, was the background for one of Burgess’s best-known cartoons. Bevin had committed himself to a bilateral Anglo-American trading agreement, which he did not feel the Cabinet would accept. Accordingly he had succumbed to a diplomatic illness and was recuperating on Lord Portal’s yacht at Poole. When the Prime Minister heard about the agreement, Bevin was summoned to Downing Street, but the Foreign Secretary had ensured that the yacht should not be in wireless communication with the shore. Fred Warner was therefore sent to sit in the yacht-club in Poole and try to establish contact by semaphore whenever the yacht sailed close to the shore. Meanwhile Burgess, acting as the intermediary between Poole and Downing Street, doodled a drawing of Bevin in a small speedboat exclaiming, ‘Ector needs me!’ McNeil added an ‘H’, showed it to Bevin and it was circulated around the Cabinet table as part of a softening ruse to bring the Cabinet on side. The cartoon is now part of the Cabinet papers.16

Apart from the Berlin Crisis, Burgess continued to work on a variety of issues for McNeil, particularly Palestine, where the Arabs had risen against the British Mandate. In the autumn he accompanied McNeil to the Third Session of the General Assembly of the UN in Paris, passing on the draft resolutions, including the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and the Cabinet’s instructions for the British delegation, to his Russian controller under the Arc de Triomphe.17

It was in Paris that a UN official, Brian Urquhart, came across him:

An evening meeting of the Balkan Subcommittee, which was trying to deal with the violent and chaotic situation on the northern borders of Greece, offered an excellent opportunity for Burgess’s propensity to shock. The group consisted of the foreign ministers of Great Britain, Greece, and of Greece’s Balkan neighbours, the latter being eminently conventional, old-fashioned communists, and Burgess’s appearance one evening, drunk and heavily painted and powdered for a night on the town, caused much outrage. When I mentioned this episode to Six Alexander Cadogan, the head of the British Delegation, he replied icily that the Foreign Office traditionally tolerated innocent eccentricity.18

In February 1947 Kim Philby had been posted to Turkey as the head of the MI6 station, eventually settling in a house at Vanikoy, up the Asiatic coast from Istanbul. It was an old Turkish structure standing alone on the shore, looking out to the left to the minarets of Aya Sophie and to the right to the Anadolu Hisari fortress. A few hundred yards downstream was the boat station, from which Kim caught the ferry to his office in the majestic Consulate General building, which MI6 preferred to the embassy in Ankara. It was here in August 1948 that Burgess arrived, probably unannounced, on three weeks’ leave, claiming to be on government business. Tim Milne, a school-friend of Philby and colleague in SIS, who was staying at the same time, later wrote:

However professional the visit, Guy was in no way inhibited from behaving the way he usually did. He came and went as he pleased. He might be out half the night, or hanging around at home all day. If he was in, he would probably be lolling in a window seat, dirty, unshaven, wearing nothing but an inadequately fastened dressing-gown. Often he would sleep there, rather than go to bed.19

Sometimes Milne, his wife, Philby and Burgess would go on countryside drives in the jeep. ‘Guy would sit at the back singing endlessly, “Don’t dilly-dally on the way” and a peculiar ditty of his own invention, “I’m a tired old all-in wrestler, roaming round the old Black Sea”.’20

Philby and Burgess would spend days out together, sometimes with Philby’s secretary Esther Whitfield, with whom Philby was having an affair, leaving Aileen at home with four young children. One evening the two men turned up at the exclusive Moda Yacht Club – Burgess was dressed in an open-necked shirt and sandals and had to borrow shoes and a tie from a waiter to be allowed in – where, with two young women, they proceeded to drink fifty-two brandies.21 On another occasion, Milne remembered Burgess, proud of his swimming and diving, one day spurred on by drink but by no means drunk, deciding ‘to dive into the Bosphorus from the second-floor balcony at Vanikoy. With no room to stand upright on the balcony rail, he fluffed his dive and hurt his back.’22 Burgess continued to be the house guest from hell and Aileen became increasingly depressed by his behaviour and bad influence over her husband.

Burgess’s cartoon with sketches of his Foreign Office collegues Fred Warner and Hector McNeil.

One night Burgess had not returned home by about midnight and Philby began to get extremely worried. Had he found himself in a drunken fight, had an assignation with a cadet at the nearby military academy, or was he meeting a Russian contact? After looking for him for almost an hour, Philby gave up. Burgess turned up the next day with no explanation. When a telegram arrived saying that Burgess was not needed back at the office and could stay another week, Philby attempted to suppress the telegram but, in the end, Burgess discovered it and stayed the extra week.

And yet for all his ‘awfulness, unreliability, malicious tongue and capacity for self-destruction’, Milne found him ‘oddly appealing. He let his weaknesses appear, something that Kim seldom did. Indeed he wore almost everything on his sleeve, his celebrity-snobbery and names-dropping, his sentimentality, his homosexuality; he never seemed to bother about covering up.’23 Milne was particularly struck by Burgess’s sentimental side. One evening Guy told the story of how the founder of MI6, Mansfield Smith Cumming, trapped after a road accident, had amputated his own leg in order to get to his dying son. When he finished telling it he ‘burst into tears, to our embarrassment more than his …’24

Burgess would recount stories about the famous and his encounters with them. ‘“If I’d had a choice”, he would say, “of meeting either Churchill or Stalin or Roosevelt, but only one of them, I wonder which it would have been”, adding, “As it is, I’ve met Churchill …”’ Milne remembered that ‘far from being a mere name-dropper; he could talk interestingly, often brilliantly, about his celebrities, and indeed about many subjects’, but he found him to be a tragic figure. ‘Unlike Kim, he did not have the nerve for the role he was called to play. I wonder if some hint of this showed itself on his visit to Istanbul …’25