On 28 July Burgess set sail from Southampton on Cunard’s Caronia, with 499 passengers on board, for the week’s crossing to New York. It was not just embassy officials who were not looking forward to Burgess’s arrival. Neither was Aileen Philby, who had a history of self-harm and had almost had a nervous breakdown after his visit to Istanbul in 1948, but his old friend Kim had agreed to let him stay for a few days, until he found an apartment for himself. She knew better, writing to friends, ‘Who do you think has arrived? Guy Burgess. I know him only too well. He will never leave our house.’1

‘My heart bled for Guy’s host and even more for his host’s wife. I thought of the cigarette ends stuffed down the backs of sofas, the scorched eiderdowns, the iron-willed determination to have garlic in every dish, including porridge and Christmas pudding, the endless drinking, the terrible trail of havoc which Guy left behind him everywhere’, Rees later recollected. ‘Yet I knew his misdemeanours would be readily forgiven, for Guy had a devotion to his friends which inspired an equal and answering devotion, and strangely enough, he never quite strained it beyond breaking point.’2

The Philbys lived at 4100 Nebraska Avenue, near American University, in a large five-bedroom, two-storey house with a classical portico. Even so, it was a tight squeeze with Kim, Aileen and baby Harry in the master bedroom, the Scottish nanny in another bedroom, and the other four children sharing two more bedrooms. Esther Whitfield, Philby’s secretary and lover from Turkey, was in the attic, reached by a retractable ladder on the landing, whilst Burgess was given a room in the basement opening out on to the back garden, which fell away gradually into woods and rough ground. Writing to Peter Pollock, shortly after arriving, he noted, ‘I am living in the Philby house which is nice – in an expanded room with bath, with a separate entrance. Not that separate entrances do much good. I will not write about “Life in Washington”, except to say that even I agree with Eric – it simply is not safe or reasonable to do anything in the city.’3

If Aileen was unhappy and Philby nervous about their new lodger, at least the Philby children – Josephine, John, Tommy and Miranda – found him a thrilling companion. He was always buying them presents, including a large wigwam, and took a particular interest in John’s electric train set, which took up part of his flat, running trains around obstacles such as a bottle of whisky. John Philby later recollected, ‘I remember his dark, nicotine-stained fingers. He bit his nails, and always smelled of garlic. Many years later in Moscow, my father told me Burgess had kept his standard-issue KGB revolver and camera hidden under my bed.’4

Burgess was very good with children and had numerous godchildren, including Josephine Philby and the sons of Goronwy Rees and his wartime MI5 colleague, Kemball Johnston. Nancy McDonald Hervey, who lived next door to the Philbys, had fond memories:

Guy Burgess was very friendly to us and we thought that he was great! We called him ‘Uncle Guy’, probably because that’s what Josephine called him, but also because we called our parents’ good friends ‘aunt’ and ‘uncle’. Guy Burgess drove a convertible – I have no idea what make or model. He drove us around in the convertible more than once and he seemed to enjoy it as much as we did. Back then, it was exciting to have a ride in a convertible with the top down and Guy Burgess was fun to be with … He was jolly and scruffy.5

If Burgess was aware of the reaction of Foreign Office officials to his posting, he certainly made no attempt to win their approval. It was customary for all new arrivals at the embassy to visit Francis Thompson, the embassy’s senior security officer, for a briefing on local security matters. Burgess did not bother, but the two were quickly to meet after a member of staff reported Burgess for leaving some classified documents unprotected in his office. Thompson took the security violation form to Burgess in his office. ‘One of my men found some papers in your office last night which should have been returned to the registry, and we have a system here which requires you to write an explanation on this form’, Thompson told him. ‘He did not apologise, as most people normally did.’ Thompson advised him to be more careful in future. ‘Burgess looked at me in a rather supercilious way, and I left him. My impression was that he was thoroughly unfriendly, and a little scared.’6

Burgess’s role in the embassy isn’t entirely clear, partly because no one wanted him or knew quite what to do with him, and partly because there are so many conflicting reports about what he did and little official confirmation.7 The embassy had some nine hundred staff, spread over several sites, but most of the important work was done in the sixty-foot stretch of corridor that constituted the chancery on Massachusetts Avenue. It was here that Burgess’s office was located by the front door, looking out on to an internal quadrangle.

Next door was Philby, the head of the MI6 station, and his secretary Esther Whitfield, and on the other side Lord Jellicoe, dealing with Balkan matters. Nearby was Geoffrey Paterson, the MI5 representative, and diagonally opposite, Dr Wilfrid Mann, who worked on atomic energy intelligence. This part of the embassy, with its grilles and locks on all doors, was known as the ‘Rogue’s Gallery’ and it suggests that Burgess’s responsibilities had some bearing on intelligence, possibly propaganda, and the need for secure communications. It’s also clear from circulation lists that Burgess, even though only a second secretary, received highly sensitive material.

According to Denis Greenhill, it was first intended that Burgess work for Counsellor Hubert Graves, who dealt with Far Eastern matters, but he refused to have anything to do with Burgess. The head of chancery, Bernard Burrows, then tried to foist Burgess onto Greenhill, head of the Middle Eastern section, who also dealt with Korea. He refused, because State Department colleagues do ‘not like to be fobbed off with a new, more junior man, who had no knowledge of the Middle Eastern area’, but he was overruled. Greenhill later remembered how Burgess ‘expressed at once a total disinterest in the Middle East and I soon abandoned any attempt to involve him in my work’.8 Thereafter Burgess had a roving brief that included picking up information gained through his wide socialising and writing general reports on the American scene.9

However, there is no doubt that he worked on Far Eastern matters; Burgess was, for example, on the distribution list for a secret cable concerning Chinese troop movements that otherwise only went to the ambassador, the military attaché and Greenhill, and amongst the heavily weeded embassy files for the period is a report by Burgess to Greenhill and Graves dated 29 August 1950, passing on information from the Chinese Nationalist military attaché, which he’d heard from an unidentified head of mission.10

Documentation shows that from his arrival at the beginning of August until the end of November, as Greenhill’s assistant, Burgess was also an alternate member of the UK delegation to the Far Eastern Commission. The commission, consisting of the representatives of eleven countries, including the Soviet Union, had been set up in 1945 by the United Nations to ensure Japan fulfilled the terms of its surrender. However, it was ignored by MacArthur and the Soviets resigned from it in February 1950, because there was no representation of the Chinese Communist Government on the commission. The position certainly gave Burgess access to classified documents, but not anything startling. He was also on the Steering and Reparations committees, and on the sub-committees dealing with Strengthening of Democratic Tendencies, War Criminals, Aliens in Japan, Occupation Costs, Financial and Monetary Problems, but as several of these sub-committees didn’t meet while he was in Washington, they cannot have been onerous responsibilities.

The legal representative from the State Department on the Aliens in Japan sub-committee, when later interviewed by the FBI, remembered how ‘after Burgess came on the committee, he was much more co-operative with the United States in connection with this proposal than had been the prior British representative. She said that he had a good attitude with respect to the work of the committee, and that he seemed to believe firmly in co-operation between the British and Americans’ though she ‘noted the odour of liquor on Burgess’s breath in the morning, and had concluded that he was a rather heavy drinker’.11

One of Burgess’s jobs was to monitor American public opinion towards the Far East, so he had wide contacts amongst newspapermen. One journalist, who met him several times between January and March 1951 at the Press Club bar of the Foreign Policy Association in Washington, remembered, ‘he was interested in questions concerning the Far East’ and that:

He seemed to be in agreement with the official British attitude, which was that the rise of communism in China was a Chinese matter which had been accelerated by the Chiang Kai-shek administration, because of the latter’s inefficient and dishonest methods. [Redaction] stated that it was of great importance to Burgess as a student of China that the Chinese situation be allowed to follow through in its own right to a natural conclusion, and that it bothered Burgess to think that the United States might try to control the Chinese situation.12

William Manchester, in his biography of General MacArthur, stated that Burgess ‘sat on the top-secret Inter-Allied Board’ responsible for policy decisions about the conduct of the war, and therefore was in a position to pass on sensitive material to the Russians, but he provides no more detail and it seems unlikely.13

‘He was a most unprepossessing sight, with deep nicotine stains on his fingers and a cigarette drooping from his lips’, wrote Dennis Greenhill:

Ash dropped everywhere. I took an instant dislike and made up my mind that he would play no part in my official duties. It took little longer to find out that he was a drunken name-dropper and totally useless to me in my work. But he certainly had an enormous range of acquaintances. He made no secret of being a homosexual, but at that time there was no link in official minds with security. Over months it was difficult for anyone to find anything constructive for him to do. I noticed that from time to time he asked me to show him classified telegrams on matters which were not his concern. I declined to do so, not because I thought he might be a spy, but because I felt sure he would not be able to resist the temptation to show off his knowledge to the friends of whom he boasted. He explained his morning lateness in coming into the embassy by ‘sinus’ trouble, caused by a blow to his head, when a colleague (Sir) Fred Warner had ‘deliberately’ pushed him down the stairs of a London night club. One redeeming gift was an ability to caricature.14

Greenhill felt Burgess took little interest in his work and that ‘he was at his most congenial on someone else’s sofa, drinking someone else’s whisky, telling tales to discredit the famous. The more luxurious the surroundings and the more distinguished the company, the happier he was. I have never heard a name-dropper in the same class.’15

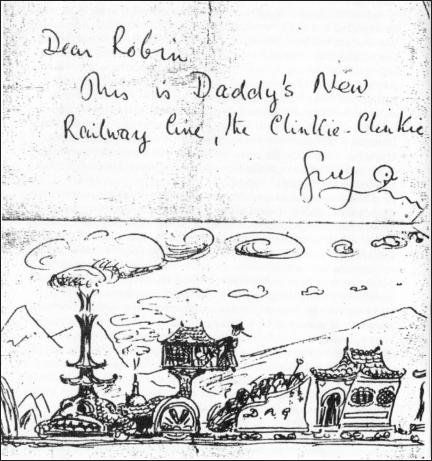

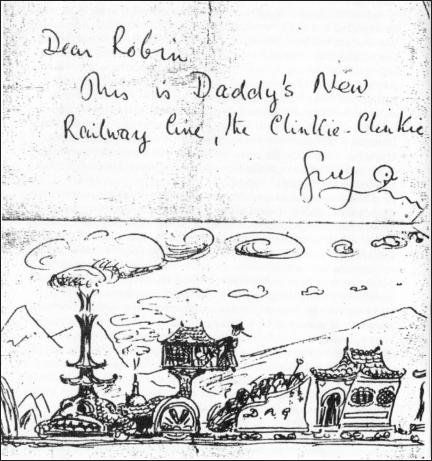

A Burgess drawing done for Dennis Greenhill’s son Robin.

According to another embassy colleague, Tim Marten, a first secretary dealing with atomic energy:

He used to appear about 11 o’clock in a suit with a waistcoat which was covered with droppings of his food. Shortly before one, he left for a diner at Dupont Circle. He had his Stammtisch – the table where he always sat – and the waiter came with a gallon jar of Californian red, a stone jar, which he plonked in front of him. Burgess couldn’t finish that, so the remains would be kept for the next day. He would have pasta … and reel out absolutely drunk and then go back to his room at the embassy where he sat, sprawled and snoring loudly, and that was his day. I don’t think he ever had any proper work to do. No one trusted him a yard.16

Somehow Burgess survived, in spite of his disdain for American values, his superciliousness and his indiscretions, because there were still flashes of the old brilliance, wit and ability to carry out his work effectively, and because he was protected. Tim Marten remembered how ‘Oliver Franks and Frederick Hoyer Millar had fought for a year to stop his being posted to the embassy, but his last job had been speechwriter to Hector McNeil … Burgess had been very useful to Hector McNeil and Hector felt sort of indebted to him and through Bevin insisted on Burgess coming to Washington.’17

One of the first things Burgess, a motor enthusiast, had done on arrival was to purchase a car – a twelve-cylinder 1941 white Lincoln convertible, to which he had added lots of gadgets. This was to be his pride and joy and a source of much irritation to his colleagues, as he parked it wherever he fancied in the embassy compound.

Kim Philby remembered ‘… the delight the Lincoln gave its new owner and it would be nice to say that it was treated thereafter with loving care. But that would give a wholly wrong impression. Love was indeed lavished on it, but not care. It lay in the garden in all weathers with its hood down, its rear compartment gradually filling up with a distasteful mess of miscellaneous junk, sodden newspapers, empty bottles, beer cans, crushed cigarette packets, spent matches and plain dirt.’18

Shortly afterwards Burgess wrote to Peter Pollock, who shared his love of cars, explaining he had already been on two trips of six hundred and eight hundred miles each, often driving at 85 mph all day. ‘I have been extremely unfaithful and bought a car that is more beautiful, more fast, more comfortable, more reliable even than the Railton. And nearly as old (1941). It is true that many think it is the best car ever made in the USA – anyhow it’s the best I dreamt of having before I arrived here, if I could find one – a Lincoln Continental.’19

A family friend of Colonel Bassett from Egypt was Emily Sinkler Roosevelt and, shortly after Burgess’s arrival, she and her husband Nicholas, a retired investment banker and cousin of Franklin Roosevelt, issued an invitation to stay at their eighteenth-century estate, Highlands, in Pennsylvania, a hundred-and-thirty miles north of Washington. The Roosevelts, some thirty years older than Burgess, were to open many doors socially for him, not least to the Alsop brothers, Joseph and Stewart, both famous newspaper columnists. Burgess became a frequent visitor to their various properties, including spending Christmas 1950 with them, where he managed to leave behind a pair of striped seersucker, blue-and-white trousers, white dinner jacket, white hairbrush, and umbrella.

In September travelling with Eric Kessler he had a weekend in Virginia, staying with a friend in Richmond and visiting the University of Virginia and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, which he found ‘the most civilised and beautiful house I had ever seen’. Later in the month he drove with a friend, probably Eric Kessler again, who despite his nervousness about Burgess’s driving was a frequent companion, to Maryland, where he’d been with Peter Pollock a few years earlier.

‘On this trip to Great Falls, Burgess brought 30 to 40 small drawings and watercolours that he had done, most of which were scenes from the Middle East’, one FBI report stated. ‘Burgess expressed love of life in that part of the world, especially the Mohammedan countries, where men are dominant and women are in the background. Burgess also expressed the opinion that the Western world was very “muddled” and said he would like to get away from it. He told [deleted] that the things he had hoped for in the way of peace, and generally improved conditions, had not come to pass.’20

In October he was back at the Roosevelts, where his hosts noticed he was drinking heavily – whisky – but not intoxicated. They ‘stated that Burgess had a brilliant mind, talked knowledgeably on many subjects and impressed them as a keen, young British diplomat who was interesting and stimulating. They advised that Burgess appeared to be emotionally unstable, being gay and exhilarated at times, quarrelsome, worried and distracted at others … Burgess was a very nervous individual, who chain-smoked cigarettes almost continuously during his visit …’21

At the beginning of November, Burgess was assigned to look after his fellow Old Etonian, Anthony Eden, probably at the behest of Robert Mackenzie, another Old Etonian. Eden was in Washington, representing the former War Cabinet, at the unveiling of a statue in Arlington National Cemetery of Sir John Dill, the British head of the Combined Chiefs of Staff during the Second World War. It was to prove a dramatic visit. Just as President Harry Truman was about to meet Eden at the White House to drive to Arlington, Puerto Rican revolutionaries attempted to assassinate the President. They were shot dead and Truman continued to the unveiling. Eden, who was to become Foreign Secretary again in October, held a series of high-level talks with the President, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Secretary of State, and it’s highly possible that Burgess, even as a junior diplomat and chauffeur, would have been present.

Eden’s thank-you letter, written from Government House in Ottawa, was to become one of Burgess’s most valued possessions. ‘Thank you so much for all your kindness. I was so well looked after that I am still in robust health, after quite a stormy flight to New York and many engagements since! Truly I enjoyed every moment of my stay in Washington, and you will know how much you helped to make this possible. Renewed greetings and gratitude.’22

China entered the Korean War at the end of November and, after Truman suggested at a press conference that he might use atomic weapons against the Chinese, Prime Minister Clement Attlee flew to Washington to remind the Americans they needed to consult Britain if nuclear weapons were to be used. As the embassy’s expert on Chinese communism and its relationship with the Soviet Union, Burgess would have been deeply involved in the crisis and would have passed on any of the discussions, not least information he picked up from Gladwyn Jebb, the UK’s ambassador to the United Nations, and his private secretary Alan Maclean, directly to his Russian masters.

A frequent destination was New York, where Burgess often stayed at the flat of Alan Maclean, his former colleague at the News Department.23 He was also seeing something of his Eton friend Robert Grant, a stockbroker and champion racquets player, and one of his first trips was to Valentine Lawford, a Cambridge contemporary and former British diplomat, whom he insisted on taking for a spin around Oyster Bay and in whom he confided he was ‘thinking of leaving the Foreign Office’.24 On these New York trips he also took the opportunities provided at the Everard Turkish Baths on 28th Street to pick up young men.

The visits to New York took on a new momentum, several times a month, usually staying at the Sutton Hotel on East 56th Street, a semi-residential hotel between 2nd and 3rd Avenue, with literary connections and a swimming pool. Alan Maclean’s flat, which he shared with an artist friend, James Farmer, was just around the corner and Burgess often stayed there, to the extent that Gladwyn Jebb formed the mistaken impression that the two men ‘shared a flat’.25 These trips tended to follow a pattern of arriving on a Friday night and returning on Sunday or Monday to Washington. Though ostensibly social, the weekends actually served another purpose. Burgess acted as a courier for Philby, which was the real reason he was living with him, and these visits were used to meet their controller, Valeri Makayev.26

Burgess was also travelling further afield. Martin Young, an Apostle and then a junior diplomat, remembered in late 1950 how he brought the diplomatic bag from Washington to Havana, where he was a twenty-three-year-old third secretary:

I asked Guy to dinner and he spent the evening at my flat in Vedado, scattering the sofa with cigarette ash and mesmerising me with his conversation. Of this I remember only two items: an account of the delights of sex with boys behind the rolled-up mats of one of the mosques of Constantinople … The other was the story of his being hauled before the head of chancery or minister in the Washington embassy after one of his flagrant speeding offences, and getting out of trouble by managing to let whoever it was catch sight of his copy of Churchill’s speeches, with Winston’s praise for Guy’s ‘admirable sentiments’ inscribed on the fly-leaf …27

Young arranged to meet Burgess first thing next morning at a café-bar by the street entrance to the chancery offices, but he didn’t turn up … ‘the driver of the Legation car which had taken him and our bag to the airport later gave me a scrap of paper on which Guy had scribbled an almost illegible drunken apology’.28

According to Stanley Weiss, a twenty-one-year-old American whom Burgess had met and unsuccessfully tried to seduce on the boat from London, he was also travelling frequently to Mexico. In spite of the two-decade age difference and the fact Weiss was heterosexual, the two men became friends. Over the next six months they would meet every few weeks, occasionally to go to films, but mainly to simply drive around town and drink. ‘He loved Beethoven and we would often talk about music. He never stopped smoking or drinking but I never saw him drunk,’ Weiss later remembered. Burgess wrote to him regularly, encouraged Weiss’s reading – in particular The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles – and suggested he apply to Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. In hindsight, Weiss realised he was being cultivated.29

The journalist Henry Brandon ran into Burgess soon after his arrival. ‘“Guy, who on earth sent you to Washington?” Burgess, not sure whether to be flattered or offended by my incredulity, replied that he had just joined the embassy staff as a second secretary concerned with Far Eastern Affairs’. After Brandon had been in Washington for about three months, he got a letter from Hector McNeil:

Saying Guy was feeling ‘lonely’ there and could I ask him to some parties of mine? So, to please Hector, I asked Burgess for drinks to my apartment and to one or two dinner parties. He was always surprisingly civil. Several times on leaving my apartment he said to me in a quasi-confidential tone of voice that he was going to spend the evening with Sumner Welles, a very rich man who used to be Under-Secretary of State … with a twinkle he suggested that he was a fine man to have an affair with …30

Burgess continued to be unhappy – about his job and life in America. In December he took the opportunity of sounding out Michael Berry, when he was in Washington for two days, about a job on the Daily Telegraph foreign desk, but with no success. Burgess had invited him to have tea with Sumner Welles, who had been the American Under-Secretary of State from 1937 to 1943 until dismissed in a homosexual scandal. Welles’s wife had just died and he and Burgess had struck up a friendship, helped by their shared interest in politics, alcohol, men and their self-destructive character.31 Berry later remembered, ‘We went to his house, which was about an hour out of Washington, in Guy’s car, and had a very ordinary tea, talking about foreign affairs. One thing I remember was that Guy had a full bottle of whisky in the glove pocket of his car, and offered me a swig directly after lunch. When I declined, he had some.’32

When he heard Joseph Alsop was hosting a party in honour of Berry and his wife Pamela that evening, Burgess tried to get himself invited. Though there was no room at the dinner, Alsop suggested he drop in for coffee afterwards. According to one account, ‘Burgess arrived drunk, unshaven, and unkempt, and soon started denouncing America’s Korean War policy’ and was thrown out.33 Berry’s own recollection was more prosaic. ‘He was full of beans, but, according to my wife, was a little drunk when he offered us a lift back to our hotel. Consequently, though I had no licence, I was made to drive his car.’34

The following day James Angleton, a senior CIA officer, was lunching in Georgetown when Burgess appeared. ‘He wore a peculiar garb, namely a white British naval jacket, which was dirty and stained. He was intoxicated, unshaven and had, from the appearance of his eyes, not washed since he last slept. He stated that he had taken two or three days’ leave and had “an interesting binge” the night before at Joe Alsop’s house.’35

Burgess explained that he intended to make a fortune working with a friend on Long Island, importing thousands of the type of naval jacket he was wearing and selling them in exclusive shops in New York. He also pressed Angleton ‘for a date when they might meet in order that he might test the overdrive on the Oldsmobile’. The encounter was duly reported back to Philby.36