On Friday 19 January 1951, the Philbys held a formal dinner party for twelve, which was to become notorious in Burgess’s path of self-destruction. Among the guests were the CIA’s head of the Office of Special Operations, which involved international liaison James Angleton and his wife Cicely; William Harvey, a former FBI agent responsible for counter-intelligence at the CIA and his hard-drinking wife Libby; Robert Lamphere, the FBI liaison to the CIA and his wife; Robert Mackenzie, the British embassy’s regional security officer for the Americas, with Geraldine Dack, one of Philby’s secretaries, and Wilfrid Mann and his wife Miriam.

The couples were enjoying coffee when Burgess returned to the Philby house about 9.30 p.m. He was:

in his usual aggressive mood and, almost immediately after being introduced, he commented to [Mrs Harvey] that it was strange to see the face he had been doodling all his life suddenly appear before him. She immediately responded by asking him to draw her. She was a pleasant woman, but her jaw was a little prominent; Guy caricatured her face … so that it looked like the prow of a dreadnought with its underwater battering ram.1

‘I’ve never been so insulted in all my life,’ Mrs Harvey shouted and stormed out of the house with her equally angry husband. Philby remonstrated it was just a joke and Burgess had meant no harm, but Harvey was having none of it. ‘He saw in Burgess’s gratuitous insult an aristocratic contempt for his unadorned Midwestern background and that of his college dropout wife.’2

Aileen was shattered. Her important dinner party had been destroyed by a man she despised. Whilst Miriam Mann and Cicely Angleton comforted her in the kitchen, the unrepentant Burgess helped himself to drinks, to celebrate his coup against Harvey. James Angleton and Wilfrid Mann, escaping from the highly charged atmosphere, went outside. On returning, Mann found Philby, in short-sleeves and bright red braces, in a darkened room with his head in his hands. ‘The man who had never been known to lose his self-control, the pride of the British service, was weeping. In between his anguished sobs, he kept saying to himself over and over, “How could you, how could you?” One Soviet spy had, in the home of another Soviet spy, insulted the man whose job it was to flush out Soviet spies. As Talleyrand would have put it, it was worse than a crime, it was a blunder.’3 Burgess might have enjoyed his momentary triumph over Harvey, but he had made himself a powerful enemy.

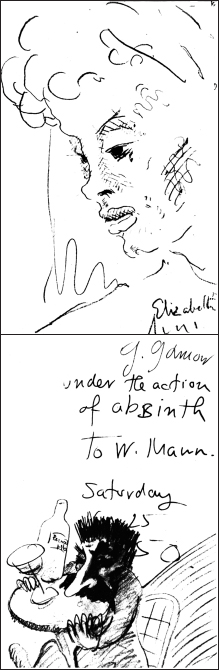

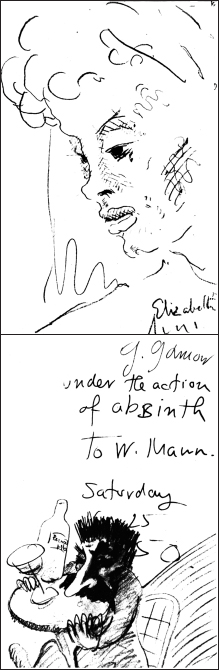

Caricatures by Guy Burgess on Wilfred Mann’s copy of Atomic Energy by George Gamow, 25 November 1950. Elizabeth was a close friend of Burgess.

Returning the next morning to pick up his car, Mann found Burgess and Philby ‘in the double bed that was facing me. They were propped up on pillows, wearing pyjamas; one, or even both of them, may have been wearing a dressing-gown as well. They were drinking champagne together, and asked me to have a glass too as a pick-me-up … I got the impression that both Philby and Burgess were enjoying the situation immensely.’4

Mann’s own loyalty has itself been the subject of much debate. In Andrew Boyle’s The Fourth Man, which led to the exposure of Anthony Blunt, Mann, under the pseudonym ‘Basil’, was named as himself having worked for the Russians. Citing confidential information from a CIA source, Boyle claimed the Israelis ‘passed on to Angleton the name of the British nuclear scientist whom they had unearthed as an important Soviet agent’ just after the Second World War, as ‘the price for uninterrupted but informal co-operation with US intelligence’. Angleton decided to ‘run the operation out of his hip pocket for at least a couple of years … Whether Hoover himself was fully informed is questionable. What can be said is that the FBI did learn eventually that “Basil” was working under CIA control as a double agent. It is impossible to be more precise than this, because no complete chronological record of the operation was kept; next to nothing was committed to paper.’5

According to Boyle, quite separately in late 1948, American cryptoanalysis revealed a Russian source inside the British embassy who had passed classified information during the final stages of the Second World War. ‘Basil’ was identified and ‘broke down quickly and easily, confessing that he had become a covert communist in his student days and a secret agent for the Soviets not long afterwards’. He was given the choice of continuing to work for the Russians under CIA direction, or ‘take whatever penalties were visited on him by American law’. In return for protection and the promise of American citizenship, ‘Basil’ agreed to be played back against the Russians. He also revealed that the Russians had penetrated British intelligence, hence Angleton failing to share his coup with the British. According to Boyle, ‘Angleton intended to use “Basil” next to test the slight suspicions he had long nursed about Philby.’6

Mann understandably vigorously denied the accusations, publishing a book challenging some of the evidence that Boyle had produced, though some of his defences were themselves found to be false – but he did not sue. Mann’s recruitment and turning is backed up by Patrick Reilly, chair of the Joint Intelligence Committee, and then the Foreign Office Under-Secretary in charge of intelligence, who wrote in his unpublished memoirs, ‘That “Basil”, who can easily be identified, was in fact a Soviet spy is true: and also that he was turned round without difficulty.’7

Those who defend Mann say his name does not appear in Guy Liddell’s diary, the Venona decrypts nor the Mitrokhin Archive, that he was several times security cleared and his FBI file is not designated R for Russian espionage, and they believe Angleton misled Boyle to protect his own reputation over Philby and Reilly simply wrote down gossip.

However, the fact Mann’s name has not cropped up in Liddell, Venona and Mitrokhin does not necessarily mean he did not spy for the Russians but simply there is no record. He could, for example, have been run by Russian military intelligence, the GRU, or outside the rezidentura. The spy writer Nigel West claims that in 2003 documents were retrieved from the KGB archive suggesting ‘that Mann may have been a Soviet spy codenamed MALLONE’ whilst Jerry Dan’s novel, based on interviews with a KGB scientific officer Vladimir Barkovsky, Ultimate Deception: How Stalin Stole the Bomb includes an interview with Mann confessing to his treachery. The jury remains out.8

Meanwhile some code-breaking investigations, in which the FBI agents at the dinner party were involved, were proceeding.9 During the previous eight years, American cryptanalysts had intercepted thousands of Soviet intelligence telegrams written in code, though only managed to partially decrypt about two thousand. In 1946 one of the analysts, Meredith Gardner, had, through a Soviet error, managed to decipher one of the messages between the US and Moscow. The operation codenamed BRIDE and then VENONA revealed that over two hundred Americans had become Soviet agents during the war, with spies in the Treasury, State Department, the nuclear Manhattan project, and the OSS. It had also uncovered an unidentifiable Soviet agent, codenamed HOMER, based in the Washington embassy in 1945, who was passing secrets. The information was immediately passed to the head of the MI6 station in Washington, Kim Philby, who in turn told Burgess.10

A few weeks earlier the decoders had decrypted a message from June 1944, narrowing the number of suspects for the spy ‘Homer’. Investigations suggested one of two men – Paul Gore-Booth and Donald Maclean. Philby immediately informed his controller Makayev and plans were set afoot to warn Maclean and exfiltrate him.11

Though neither Burgess nor Philby had yet come under suspicion of espionage, Burgess’s cruising of Washington bars and lavatories had begun to excite the interest of Inspector Roy Blick of the Washington Metropolitan Police Vice Squad, who now put him under surveillance, reporting that he had been seen on two occasions escorting a striking platinum blonde, and in the company of Russians eating at the Old Balalaika Restaurant in downtown Washington. Meanwhile Valentine Vivian, now an SIS security inspector and visiting America, warned Philby that his association with Burgess was unwise.12

Burgess’s increasing disillusionment with political events continued. Writing to Peter Pollock in mid-January from Nebraska Avenue, with instructions on cashing some cheques he’d sent, he admitted, ‘Life is not hell at the moment. But it is so absolutely bloody in its official aspects, I mean American Policy, as to make even you most apoplectic … Can one last, or will one go quite mad?’13

Interviewed later about his Washington sojourn, Burgess spoke of:

The appalling experience I’d had at the embassy in Washington – that terrible and ignorant subservience to the State Department that I’ve told you about – and the realisation you see that this was what my life would be for the next twenty years. I wouldn’t have minded nearly so much if I could have sat in the Foreign Office all the time. But I knew I couldn’t do that: everybody has to serve in the various missions overseas … and Washington is supposed to be one of the top embassies – so what on earth could the others be like?14

A journalist who saw him several times that spring remembered that Burgess ‘drank heavily but was able to “hold his whiskey”, in that he could drink six highballs, “without turning a hair”. He stated that although Burgess would drink an unusually large amount of whiskey, he never seemed to even approach becoming intoxicated … He found Burgess “restless and agitated” and:

feeling that the United States was headed for doom because of having gotten confused and bogged down with regard to Oriental affairs … Burgess was very free in manner and seemed almost desperate in his seeking friends. He stated Burgess made a very poor personal appearance, pointing out that he never wore a hat, his hair was always tousled, and his fingernails were always very dirty … Burgess liked to drive his convertible car with the top down in the wintertime and to make a lot of noise with it. He stated that Burgess would continually pace the floor while talking and was a very unconventional type of individual … expressed the opinion that it would be interesting, from a psychological point of view, to determine the reason for Burgess’s ‘flamboyance’ and his apparent revolt from conventions.15

He recollected how ‘Burgess seemed to consider the fact that investigation of homosexuals was being made by Congress as a personal affront … that his meetings with Burgess were getting rather monotonous, because all that Burgess talked about was China, the United States, and his Lincoln Continental automobile’, adding that after Burgess took him to lunch ‘he had parked between two signs designating a no parking loading zone, telling [redacted] that he didn’t have to worry about being illegally parked since he was a diplomat’.16

Burgess was approaching forty, still a second secretary, often being given mundane work and aware his Foreign Office career was going nowhere. He and the ambassador had a mutual-hate relationship and Burgess was gradually being demoted from one job to another, until to his indignation he was left administering the George Marshall scholarships. His diabetes was leading to blackouts and his dependence on drink, always there, was becoming more critical. Senator Joe McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade was in full swing and Burgess could be aroused almost to hysteria by McCarthy’s identification of communism with homosexuality. He was also becoming increasingly angry about American foreign policy. The security violations continued, with constant complaints to Thompson about carelessness, classified papers not locked away, and so on. It was almost as if Burgess was trying to get himself dismissed, not least by his truculent responses. Philby later wrote:

For all his apparent waywardness, Guy was dreadfully afflicted by awareness of his failures. Indeed the waywardness and the failure fed each other, causing a vicious spiral, spinning downwards. A lesser character might well have succumbed completely, years earlier. But Guy had a stubborn streak of integrity which no outrage could wholly subdue. Repeatedly he sat in judgement on himself, pronouncing harsh sentences. But he had no means of executing them and the sentences remained in the air. The outcome was galling unhappiness. He stood shame-faced in his own presence.17

Most of his colleagues tried to avoid him. Patsy Jellicoe remembers him covered in dandruff and an ‘awful show-off. He knew everyone and would tell you … no one liked him because he pretended to be so grand. He dropped names to be important … He was just irritating’, adding that ‘he was always propositioning everyone’.18 One colleague, however, with whom he remained on good terms was Esther Whitfield. After they had met in Istanbul, they had stayed in touch when Esther was posted to London between September 1948 and March 1950. They now saw much of each other and even went away for weekends together. Philby told MI5:

In the meanwhile, his relations with Miss Whitfield developed. I did not pry into the matter myself, partly because I was afraid of being asked for advice. On the other hand, I thought it possible that marriage might prevent Guy from going completely to the dogs; on the other hand, I doubted whether Miss Whitfield could take the strain. My information on the progress of the affair is therefore derived from rather shoddy de-tails derived from Guy himself. I gather that he did make a definitive proposal on one occasion, but that her reply was non-committal.19

Alan Davidson, private secretary to the ambassador Oliver Franks, had first encountered Burgess when he joined the Foreign Office in 1948 and was serving in the Northern Department. In Washington, Davidson would sometimes meet Burgess for drinks with Pat Grant, the personal assistant to the ambassador. One day in the spring of 1951, Davidson had a telephone call from the security guard at the front door, saying there seemed be a fire in Burgess’s office. They couldn’t get in, but there was smoke coming from under the door, and there had been no response when he’d knocked. Davidson told him to break down the door. The door was solid, and after they had been battering away for some time, to their astonishment it was opened from the inside. ‘At that point Guy appeared at the door looking a bit flustered. “I was burning a few papers.” It seemed perfectly natural for someone like him to be burning private correspondence. Oh Guy, he was always doing crazy things. It fitted in with the messy side of his behaviour.’20