Burgess’s health was now beginning to give him trouble, as he explained to Tom Driberg:

I can’t quite get it clear about my heart. It’s certainly what we call Angina Pectoris with which you can live till 90. It’s equally certainly a worrying nuisance. Amongst other things it interferes with work – and if one goes out without ones Nitroglycerine tablets – which remove the symptoms in a few minutes unfailingly but which are no cure – one may be caught. My attacks for some reason are normally first thing in the morning, either when I wake up (sometimes they wake me up) or, if not then, after breakfast. It interferes with work by having one v tired – and indeed even if no attack one seems to feel tired always. Exercise also brings it on, particularly walking upstairs. Pain oddly not in heart but in chest – particularly in arms (not much in chest). According to electrocardiograms, one of which was rather bad, they say, I have had it for a long time … I beg you to say nothing at all to my mother.

Shortly afterwards, dining with Yuri Modin in a Moscow restaurant, he collapsed with what seemed to be a heart attack, though it turned out to be too much drink. When he recovered, he was ‘very emotional’, saying ‘he did not want to die in Russia’.1

In August Jack Hewit had written to Driberg asking for Burgess’s address. In 1956 he had written a rather bitter letter, which he now regretted – ‘it’s all rather “old hat” now, and I really would like to hear from him again’.2 James Pope-Hennessy had also tried to make contact through Harold Nicolson, sending a copy of his biography of Queen Mary that Burgess had not acknowledged.

At the beginning of February 1960, hearing Stephen Spender would be in Moscow, Burgess rang him – at 1.15 a.m. – and they arranged to meet the next morning. Spender was struck by how he had changed:

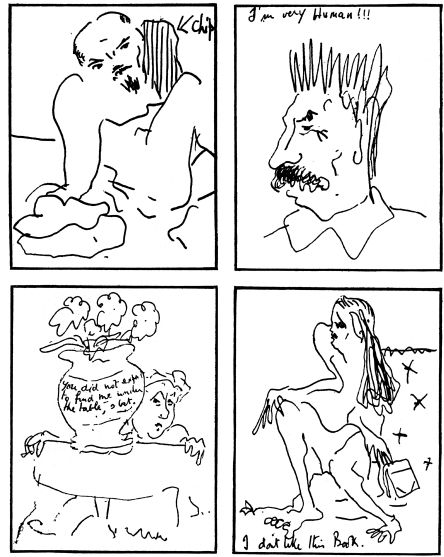

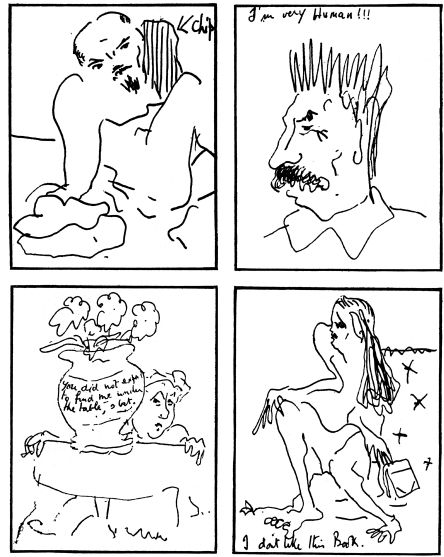

According to psychologist Mayo Wingate these Burgess doodles reveal ‘A strong resentment to feminine domination from which the artist was trying to break away … a lightly neurotic type … it is highly probable that the man who drew these is suffering from a split personality. He has strong leanings towards escapism and there is a rebellious streak in his nature, an eccentric and a fighter but at the same time a shrewd negotiator.’

… looked at full-face he was quite like he was before – somewhat florid, the same bright eyes and full mouth. Side-face, he seemed very altered indeed – almost unrecognisable: thickset, chin receding, eyebrows with tufts that shoot out and overhang … He had a seedy, slightly shame-faced air and a shambling walk, like some ex-consular official you meet in a bar at Singapore and who puzzles you by his references to the days when he knew the great, and helped determine policy.3

Burgess was still working for the Foreign Language Publishing House, where he was championing Jane Austen and Anthony Trollope, and the two men discussed books that might be translated. Burgess invited Spender back for lunch, telephoning his cook with gusto, ‘We shall lunch off grouse!’ As they waited for a taxi, he asked a policeman how to get one that was not pre-empted by Intourist, adding, ‘Moscow policemen are sweeties.’4

Before lunch the two men walked around the Novodevichy monastery and discussed religion, Burgess claiming to be a nonbeliever. ‘It’s the intellectual betrayal involved. Last time I met Christopher [Isherwood] I made him cry by attacking him for his religion.’5 Then they moved on to treachery. ‘Everyone gives away information,’ argued Guy. ‘When Churchill was in opposition he used to give away confidential information about what the government was thinking to Maisky, then Russian ambassador … during the war, there were frequent exchanges of information between the British and the Russians, in which the rules of secrecy were more or less ignored, or considered to be suspended.’6

Spender was struck by the extent to which Burgess had reinvented the past in his mind. He asked him whether he had made friends in Moscow and Burgess replied in the affirmative. ‘Are they like your friends in England?’ ‘No one has friends anywhere like they have in England. That’s the thing about England.’7

Graham Greene also saw him and later remembered, ‘I don’t know why he particularly wished to see me as I didn’t like him, I was leaving early the next morning, and I had begun a serious attack of pneumonia. However, curiosity won, and I asked him for a drink. He drove away my very nice translator, saying that he wished to be alone with me, but the only thing that he asked of me was to thank Harold Nicolson for a letter and on my return to give Baroness Budberg a bottle of gin!’8 Burgess later admitted to Harold Nicolson, ‘I fear I behaved inconsiderately and tried him and exhausted him by keeping him up – the temptations of parish-pump gossip were too great.’9

The theatre director Joan Littlewood was another visitor, bringing some requested curry powder when Theatre Workshop went to Moscow. She remembered how ‘Guy Burgess was always phoning my home at Blackheath, because my friend Tom Driberg was staying with me and Guy adored gossip about politicians. He missed London terribly … Tom told me how Guy’s eyes filled with tears as he talked about home. He asked Tom to help him get back, apart from anything else he wanted to see his mother, who was old and not well. Tom tried but didn’t succeed. Guy was no spy … He didn’t know the final destination when he set out.’10

When in August 1960 the journalist James, later Jan, Morris came to report the trial of the American pilot, Gary Powers, whose spy plane had been shot down over the Ukraine, Burgess contacted him and the two had champagne and caviar in Morris’s room at the Hotel Metropol. Morris felt ‘sorry for the poor wretch, whose Foreign Office elegance was by then running to fat, whose manners had become a little gross, but whose humour was still entertaining’.11

Morris wrote later, ‘He was sent the Guardian by mail from England, and was chiefly anxious to talk about everyday affairs at home – new books, teddy boys, changing tastes, and politics … He gave me the impression that, for all his almost hearty air of assurance, his whole life had collapsed around him, and that nobody really much wanted him, either there or here. I couldn’t help feeling sorry for him, for he seemed almost a parody of a broken man.’12

When Morris said he had to go as he had a ticket for the Bolshoi, Burgess said he’d come along as well. He knew the management well and there was bound to be a spare ticket. ‘We walked through the snow to the theatre, and in the lobby I left him to deposit my coat and galoshes in the cloakroom – “quite all right, old boy,” he said (for he spoke in a dated vernacular), “I’ll just fix it up with the manager and meet you here.”’ When Morris returned Burgess had disappeared. ‘Had some secret policeman spotted him and warned him off? Had he decided that I was not the kind to be photographed in compromising positions at orgies? Was he simply not so well in at the Bolshoi as he had implied? I don’t know. I never saw him again.’13

Burgess had known the painter Derek Hill through the Reform Club and Anthony Blunt, and had gone on holiday with him, Andrew Revai and Peter Pollock to Ascona in 1947. Hill had become one of Burgess’s correspondents. Hill now paid Burgess an unexpected visit in the summer of 1960, bringing some ‘He-Tan’ for Tolya and pyjamas for Burgess, which he passed on to Tolya. ‘The pyjamas you brought for me fitted him perfectly and were the centre of attention on the rather grand beach of the sanatorium of the Council of Ministers at Sochi where I stayed. He in town lodgings and commuting in salmon-coloured Van Heusen pyjamas with a beige face on a bus to the beach.’14

Another visitor, with his wife, the painter Mary Fedden, was the artist Julian Trevelyan, who had been a contemporary at Trinity. As they arrived by boat in Leningrad, a man handed them a small piece of folded paper that read: ‘Come and see me the moment you reach Moscow. Guy Burgess’. ‘And every day we were in Moscow, we saw him, because he was so eager to talk to English people, and people from home, and he was very homesick, longed to come home, but knew that he would go to prison if he did,’ remembered Fedden. They, too, went with him to the Novodevichy monastery, where it was clear he knew the clergy well, and on a picnic with him and several Russian artists, bathing in the Moscow River.15

Frederick Ashton, on the Royal Ballet’s first visit to Russia in June 1961, was keen to meet his old wartime friend from the Café Royal – ‘I liked him very much … He was fun and lively’ – and Burgess ‘sent a message to me somehow to come and see him’, but the British embassy refused to let them meet.16

Also in Moscow in the summer of 1961 was ‘Brian’, a recent Cambridge graduate and gifted linguist working for the Foreign Office, who had obtained an introduction to Burgess from Tom Driberg. He recalled that Burgess’s ‘cut-glass accent is blunted; the midriff and jaw-line not what they were; no hand tremor though; a slightly lumbering gait; an ill-fitting suit that speaks more of Red Square than Savile Row (whence he had, at some point, ordered several suits). The charm and wit are still very much there along, rather flatteringly, with a distinctly proactive interest in me and my doings, and an almost childlike hunger for first-hand news of London and, indeed, of anything British’, but what most struck Brian was Burgess’s emotional intelligence. ‘After several meetings,’ he said, ‘Burgess struck me as lonesome, emotional and with a disproportionately strong urge to help me.’

Soon after visiting him, Brian found himself in need of such help, after being caught in a homosexual honeytrap whilst on holiday in Sochi. He was threatened with prison or becoming an informer. Knowing no one he could turn to and terrified by the implications for his career, he approached Burgess, who immediately swung into action with calls to various Soviet officials.

‘Indeed, Guy must have moved heaven and earth to help me as he had finally prevailed on a top Soviet mandarin to abandon his holiday, return to Moscow and meet me in his dustsheet-covered apartment.’ Brian heard no more from anyone and went on to have a distinguished career as a journalist.

‘I think Guy Burgess was very conflicted. He certainly saved me from a show trial. In saving me I wondered if he was making amends for his treachery. I gave him a cause and arguably he saw me as an act of redemption.’17

Burgess’s sympathies may have been triggered by his own experience early on in Russia. Modin recounts that when Burgess was ‘vacationing on the Black Sea in Sochi, he had an incident when he was propositioning a man and he was placed under arrest by the militia … It was very hard for him.’18

That Christmas 1960, Burgess asked Driberg whether he should offer himself as the Moscow correspondent of Reynold’s News:

I am not a journalist but I do know more than many other journalists do and certainly more than Embassy … Tolya has got a good new job – organising and playing in concerts in a big factory. He’s very happy ‘living among real workers’. And I continue to be v. happy with him. I don’t know what saint in yr calendar to thank. Perhaps only Greek Church, or Armenian, has such a saint. I do wish you were similarly suited. It’s the best thing. Politically, I congratulate you on being both brave, truthful and prudent. I am only the first two.19

May Harper, whose husband Stephen had come out as Moscow correspondent of the Daily Express in 1961, remembers meeting Burgess at her engagement party given by the Burchetts. She felt sorry for Burgess. ‘He was pathetic, a maudlin drunk with food spilt down his suit and tie. He looked ill – flabby and pasty. What I remember most vividly is his slack mouth and the weaselly-looking Russian who came with him. Victor must have been twenty years younger and looked evil.’20

In the last six months of Harper’s posting, Burgess regularly rang him when he knew his Russian lesson finished. ‘For some reason, probably because he was homesick, he used to ring me almost every morning precisely at 10 o’clock for a long chat, mainly about the dirt he knew about Lord Beaverbrook.’21

A new confidant was Jeremy Wolfenden, who had been sent to Moscow by the Telegraph in April 1961. Wolfenden, whose father chaired the commission which legalised homosexuality in 1967, was some twenty years younger than Burgess, but they immediately became close friends. Wolfenden had been the top scholar at Eton and gained a history scholarship to Oxford, where he had taken a First in PPE and been a Fellow of All Souls. He shared Burgess’s Eton schooling, homosexuality, love of conversation, talent as a mimic, preference for alcohol over food, left-wing politics, intellectual arrogance, and desire to épater le bourgeois.

What Burgess didn’t know was that they had more than that in common. Wolfenden was a double agent, an MI6 informant who had been photographed in a homosexual honeytrap – Wolfenden professed to be so delighted with the pictures that he requested enlargements – and was being blackmailed by the Russians. When Burgess decided to give an interview, it was to Wolfenden. ‘In his own disreputable way, Guy Burgess is very amusing,’ Wolfenden wrote, ‘but he has to be taken in small quantities … apart from anything else, to spend 48 hours with him would involve being drunk for at least 47. He has a totally bizarre, and often completely perverse [idea] of the way in which the outside world works; but he makes up for this with a whole range of very funny, though libellous and patently untrue, stories about Isaiah Berlin, Maurice Bowra and Wystan Auden.’22

Journalist Ian McDougall saw this odd behaviour when he and the Observer correspondent Nora Beloff entertained Burgess at a private room in the National Hotel. Burgess arrived drunk and during the course of the meal became steadily drunker, until halfway through dinner he:

unceremoniously removed his shirt, complaining of the heat – it was a Moscow July at its sultriest – and revealed a very hairy chest. My guess is that he would have done the same even if we had been eating in the public dining-room. We had a long argument about, of all things, religion. He knew a great deal about the history of the Papacy, and I formed the strong impression that his communism, as is often the case with a certain type of intellectual, was one facet of a deep religious instinct … I also formed the impression that, if he had not consistently drunk so much, Guy Burgess would have been an outstandingly intelligent man, and that the early image he was given in the press – that of a sidekick to Maclean – was probably the reverse of the actual relationship between them.

To the two journalists, he claimed he was working for Russian radio and television studios monitoring British broadcasts.23

Nora Beloff had first met Burgess through a letter of introduction from the Soviet commentator Edward Crankshaw. Burgess had promptly rung her and invited her to his flat. ‘Burgess was a flabby, shabby man with badly broken teeth … He met me with an endearing smile and disarming candour. “You will have heard that I normally prefer boys,” he said, “but I will make an exception in your case.”’ They met ‘fairly frequently’ and Beloff joined him for a holiday in Sochi, where she even danced with him. ‘He gave me a few basic tips about how to treat the bureaucracy – for instance, to bang your fist on the table and outshout them. Later, when he used to come to visit me, and we ordered meals in my Intourist suite at the National Hotel, he would storm at the servants until we got adequate service.’24

Norman Dombey, an exchange graduate student at Moscow State University in the autumn of 1962, was introduced to Burgess through Jeremy Wolfenden, with whom he had been at Magdalen College. He visited Burgess at his flat, which he thought large by Soviet standards, noting that with the exception of the guards at the entrance, ‘The flat could have been in Chelsea. There was a pile of New Statesman. He had subscriptions to various British papers. Burgess looked to me like a Western intellectual.’ He found him well-informed on British politics and the two men talked about the failures of Soviet communism and how the Chinese model was better, and Burgess lent him Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China. He also remembered how Burgess spoke a lot about his mother, but an attempt to meet again had to be cancelled because Burgess was ill.25

A regime of little food and excessive alcohol had taken its toll on Burgess’s health. In the spring of 1960 he had spent time in a sanatorium in the park of Prince Youssopoff’s Archangelsk Palace just outside Moscow, being treated for arteriosclerosis, ulcers and arthritis.26 He wrote to Nicolson, ‘The house itself which resembles Chiswick and Osterley and might have been built by the brothers Adams … is a museum full of Herbert Roberts but one good Titian, one very good Tintoretto.’27

During the summer of 1961 he had two operations for his ulcer and in October he was hospitalised for hardening of the arteries, quipping, ‘I think it was Churchill who said nobody does any good work who has not had hardening of the arteries at 40 or 50.’28 The next month he almost died.