The 14th Dalai Lama is the head of state and the spiritual leader of Tibet. He has traveled the world sharing his views on compassion, tolerance, harmony among religions, and Tibetan Buddhist values. The Dalai Lama’s extensive humanitarian efforts have earned him the name “His Holiness.”

The 14th Dalai Lama was born on July 6, 1935, in Takster, a small village in northeastern Tibet. His mother and father were hardworking farmers and horse traders. They named their son Lhamo Thondup.

Lhamo was the fifth of sixteen children. Seven of his siblings died at a very young age. This was extremely troubling to his parents, but they took solace in Lhamo’s bright and curious nature. At the time of Lhamo’s birth, the Tibetan people were led by the 13th Dalai Lama. Many Tibetans believe that Dalai Lamas are reincarnations of a Buddhist deity known as Avalokitesvara, who is the human form of compassion. To become a Dalai Lama, one must be chosen. When it is time for a new Dalai Lama to be named, religious officials search the world for months. Dalai Lamas are considered those with exceptional spiritual abilities.

The Dalai Lama as a young boy

In an effort to locate the 14th Dalai Lama, a search party was formed. At the time, Lhamo was two years old. The 13th Dalai Lama, who had died, had been placed in an embalmed state, with his head facing in a southeast direction. One day, it was noticed that his head had mysteriously turned to face northeast. The search party took this as a sign. Around this same time, a government official called Reting Rinpoche had a vision while spending time at a sacred lake. In his mind’s eye he saw the region where little Lhamo and his family lived. Reting Rinpoche also envisioned a one-story house with a specific kind of gutter and tiling on the outside.

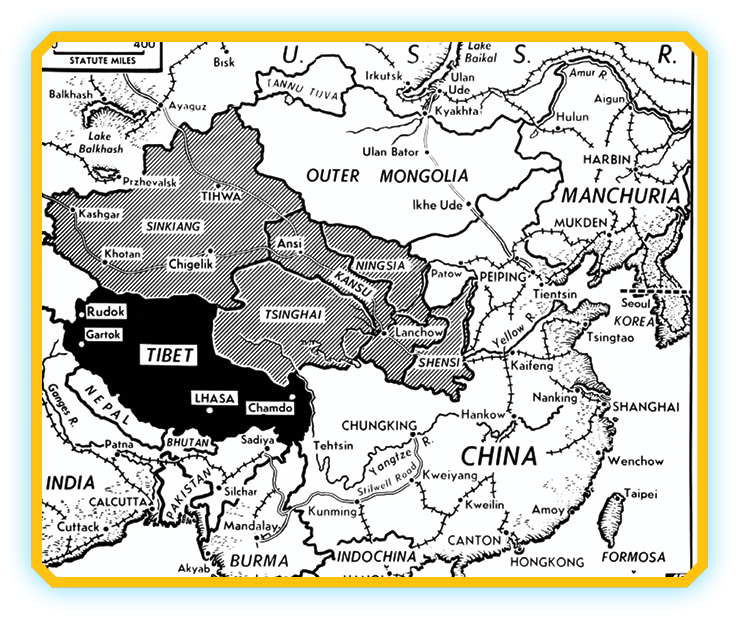

Map of East Asia

The search team looked throughout the region until they found Lhamo’s home, which matched the dwelling in Reting Rinpoche’s vision. To make sure they’d come to the right place, they presented Lhamo with several items. Only some of the things had belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama. The legend says that Lhamo picked out only those toys that were once owned by the previous Dalai Lama. As he reached for each toy, he proclaimed, “It’s mine! It’s mine!”

To those watching, this was all the proof needed — Lhamo was meant to be the 14th Dalai Lama! The officials who had witnessed Lhamo’s claiming of the things gave him a new name. They called him Tenzin Gyatso. The name Gyatso comes from the Tibetan word for ocean. The word Dalai means “ocean” in the Mongolian language. Lama means “guru” in Sanskrit, the ancient language of Buddhism. When combined, the words Dalai Lama mean “Ocean Teacher,” or “a teacher whose spirituality is as deep as the ocean.”

Buddhist monks

Before Tenzin could officially assume the role of the Dalai Lama, he needed proper schooling. While Tenzin focused on learning, the regent—a secondary government official—served as the head of state. Most of Tenzin’s studies came from two male teachers who were responsible for instructing the boy in the essentials of what he would need for his future role as the Dalai Lama. Tenzin’s lessons were rigorous, but they sparked his imagination as they prepared him for leadership.

On November 17, 1950, when Tenzin was fifteen, he was formally enthroned as the Dalai Lama, the ruler of Tibet. As part of his appointment, Tenzin was given the full name Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, which means “Holy Lord, Gentle Glory, Compassionate, Defender of the Faith, Ocean of Wisdom.”

The Dalai Lama with his family in 1956

The Dalai Lama’s spiritual fortitude and leadership abilities were immediately tested. Prior to his appointment, the army of the People’s Republic of China had invaded Tibet. The Chinese government succeeded in incorporating Tibet into the People’s Republic of China territory, thus suppressing the Tibetan people and their land, and placing them under Chinese rule.

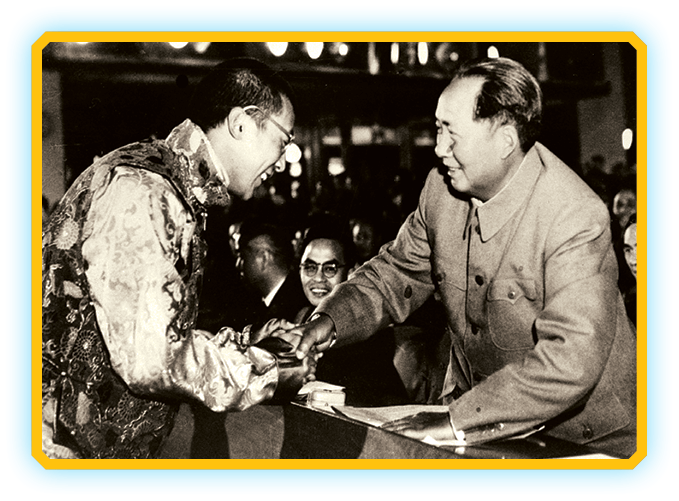

In 1954, when the Dalai Lama was nineteen, he traveled to Beijing to meet with Chinese leader Mao Zedong. The Dalai Lama arrived with peace as his top priority. It was his hope that the Chinese government would release Tibet as a free state. But the Chinese government was not willing to give Tibet its independence. This greatly troubled the Dalai Lama. He could not effectively lead the Tibetan people if they were governed by the People’s Republic of China. Chinese rule served to oppress the Dalai Lama’s power.

The Dalai Lama shakes hands with Chinese leader Mao Zedong in 1954

In 1956, the Dalai Lama visited India to celebrate the Buddha’s two thousand five hundredth birthday. While in India, the Dalai Lama met with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to tell him about Tibet’s declining conditions. He asked the prime minister if he could remain in India under political asylum. This would allow him to escape persecution and live freely. At first, the prime minister did not want the Indian government involved in the struggle between Tibet and the People’s Republic of China. He believed that to allow political asylum for the Dalai Lama was an act of anti-peace. It would mean that India was intervening in the conflict between the two nations.

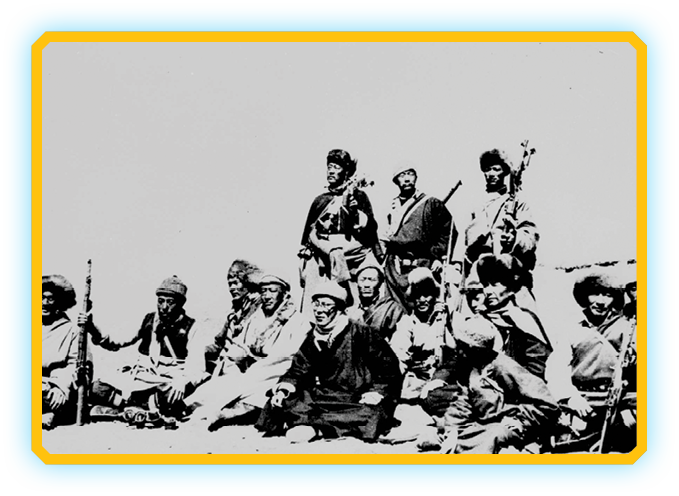

But as the struggle raged, the Dalai Lama’s choices for a peaceful existence became limited. While the government of Tibet stayed intact under the authority of China, the Tibetan people were angered by their complete lack of autonomy. This led to an uprising of the Tibetan people in 1959. On March 10, in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, armed men struck out against the Chinese army in a brutal rebellion. The uprising enraged many citizens and government officials. The Dalai Lama and his advisors came to believe that the Chinese government had plans to assassinate him in an effort to further weaken Tibet. The People’s Republic of China considered the Dalai Lama to be a leader who represented outdated religious beliefs that were not in keeping with China’s Communist values. Because of the Dalai Lama’s actions on behalf of Tibetan self-rule, the Chinese government accused him of being a traitor. They had also branded him a terrorist, blaming him for Tibet’s rebellion. Now the Dalai Lama was forced to flee Tibet. He and tens of thousands of his followers fled to northern India, where they could live safely and establish an alternative government.

The Dalai Lama at a military camp in India, 1959

In an effort to gain support for Tibet, over the years, the Dalai Lama has petitioned members of the United Nations. The United Nations General Assembly has established several resolutions that have called on the Chinese government to respect the human rights of Tibetan people, to varying degrees of success.

When the Dalai Lama was twenty-three years old, he completed his formal education by taking a rigorous university exam that was administered in three parts. The exam was held in January 1959 at a holy temple in Lhasa, Tibet.

To pass the test, the Dalai Lama had to appear in front of a large audience of scholars who posed questions that the Dalai Lama had to answer verbally. He passed all aspects of the exam with honors and was awarded a geshe degree, the highest-level degree a student can earn in the field of Buddhist philosophy.

With his education completed, the Dalai Lama was even more ready to serve as a leader. One of the Dalai Lama’s goals has been to gain autonomy for the Tibetan population living within the People’s Republic of China. In 1963, he issued a constitution that outlined reforms, which called for a democratic government. He based the constitution on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that all human beings are entitled to peace, justice, and freedom. The Dalai Lama’s constitution was named “The Charter of Tibetans-in-Exile.” The charter fosters freedom of speech and the right to select and practice one’s chosen religious beliefs. Also part of the charter’s code is the right for Tibetan people to assemble as they wish and to move about freely, as individuals or in groups. The charter was submitted to the Eleventh Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies. After years of deliberation, the charter was passed on July 14, 1991. While the Dalai Lama’s steps toward strengthening his people have brought worldwide attention to Tibet’s struggles, the Chinese occupation of Tibet continues. Freedom of speech, religion, and assembly are still limited because the Chinese government has shown great resistance in adopting a peaceful reconciliation with Tibet. Protests and “Free Tibet” rallies in China and many other nations have sparked volatile reactions. In some instances, demonstrations have become violent. The Dalai Lama has worked unceasingly to promote a peaceful resolution to this conflict.

Tibetan exiles holding pictures of Tibetans who have immolated themselves in protest against Chinese rule at a demonstration in 2012

In the 1980s, the Dalai Lama sought to gain support for his cause by proposing what he called the Five Point Peace Plan for Tibet.

The Dalai Lama presented his plan on September 21, 1987, in Washington, D.C., at the U.S. Congressional Human Rights Caucus, a gathering of men and women who had joined together with a goal — lasting peace throughout the world.

The Dalai Lama spoke with passion, dignity, and conviction. His plan pinpointed five new peace initiatives:

1. Tibet becoming a sanctuary where enlightened people — those committed to spiritual growth — can exist in what the Dalai Lama called a “zone of peace.”

2. An end to what had become a massive transfer of the Chinese population into Tibet, which was weakening Tibet’s cultural traditions and heritage.

3. A restoration of fundamental human rights and democratic freedoms in Tibet.

4. The abandonment of China’s use of Tibet for the production of nuclear weapons and the dumping of nuclear waste.

5. The beginning of earnest negotiations on behalf of the troubled relations between the Chinese and Tibetan people.

The audience agreed with the Dalai Lama’s brilliant plan. Many offered to help him promote the plan by sharing it with others and seeking support for Tibet.

The following year, on June 15, 1988, the Dalai Lama was invited to Strasbourg, France, to address members of the European Parliament. He proposed an additional element to the plan — the creation of a self-governing Tibet that would work in association with the People’s Republic of China.

The Dalai Lama and French president Nicolas Sarkozy

With this important aspect added to his Five Point Peace Plan, it was later called “The Strasbourg Proposal.” The other members of the Tibetan government-in-exile carefully considered the revised plan. In 1991, they rejected the proposal, calling it invalid due to the tremendous resistance and negativity from Chinese government leaders. Having served as the leader of this government, the rejection greatly disappointed the Dalai Lama.

For his nonviolent efforts and policies to gain justice for Tibet, the Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. In their citation, the Nobel committee emphasized that the Dalai Lama has “consistently opposed the use of violence” and has instead “advocated peaceful solutions based upon tolerance and mutual respect in order to preserve the historical and cultural heritage of his people.” Additionally, the Dalai Lama was the first Nobel Laureate whose concern for global environmental problems was also recognized as part of his Nobel acknowledgment.

The Dalai Lama receiving his Nobel Peace Prize

In his Nobel Prize speech, the Dalai Lama paid tribute to Gandhi’s tradition of nonviolence in the face of aggression, which has served as inspiration for his own peace philosophies. He said, “I believe all suffering is caused by ignorance. People inflict pain on others in the selfish pursuit of their happiness or satisfaction. Yet true happiness comes from a sense of peace and contentment, which . . . must be achieved through . . . love and compassion.” He spoke of his belief that “everyone can develop a good heart and a sense of universal responsibility with or without religion.”

Free Tibet protester

The struggle for autonomy for Tibet has continued. As the 2008 Olympics, held in Beijing, approached, extreme unrest broke out in Tibet. There were violent protests — condemning the Chinese for their ongoing mistreatment of the Tibetan people — in which men and women lost their lives. The Dalai Lama pleaded for peace, but none came. This frustrated the Tibetan people. There were those who felt the Dalai Lama’s words were wasted and that they didn’t help.

The violence — and the expression of disappointment by his people — were so deeply troubling to the Dalai Lama that on March 18, 2008, he threatened to give up his duties as Tibet’s spiritual and political leader. No Dalai Lama had ever done this. But instead of quitting, the Dalai Lama proposed ideas for how the role of the Dalai Lama could be fulfilled in the future. His ideas included having a woman as the next Dalai Lama, having no Dalai Lama, or having two Dalai Lamas — one being his approved successor and one being China’s approved successor — who would share the Dalai Lama duties and work together toward a common solution. His ideas have not been fully embraced, though are still under consideration.

Many wonder if a peaceful reconciliation between China and Tibet will ever come. The Chinese government has made no effort to free Tibet. There are some who believe the Dalai Lama has not been proactive enough in his peace pursuits. He has been deemed an ineffective peace warrior by his dissenters. The Dalai Lama has said, “Nonviolence means dialogue, using our language . . . There is no hundred percent winner, no hundred percent loser . . . that is . . . the only way.”

March 10, 2011, marked the Dalai Lama’s fifty-second anniversary of his exile from Tibet. On this day, he announced that he would make changes to the Tibetan government-in-exile’s constitution. As part of these changes, he would relinquish his duties as Tibet’s head of state and no longer hold his role as a political leader. Under the new constitution, Tibet’s new leader would be an elected official. The Dalai Lama stated, however, that he would keep his position as a religious dignitary. By proposing these changes, many felt the Dalai Lama was defying thousands of years of Tibetan custom. For centuries, it has been believed that Dalai Lamas are chosen, not elected — that each new Dalai Lama is a reincarnation of the last. To ensure the future of the Dalai Lama’s role, he said, “no recognition or acceptance should be given to a candidate chosen for political ends by anyone, including those in the People’s Republic of China.” Though the selection of the 15th Dalai Lama and conflict between China and Tibet are uncertain, there is little doubt that the 14th Dalai Lama is a man whose abiding commitment to peace and compassion has inspired many to live their present lives with tolerance and to strive for harmony among people everywhere.