Chapter 7

Use of geospatial

tools during

enumeration

Fieldwork benefits of using GIS/GPS and imagery

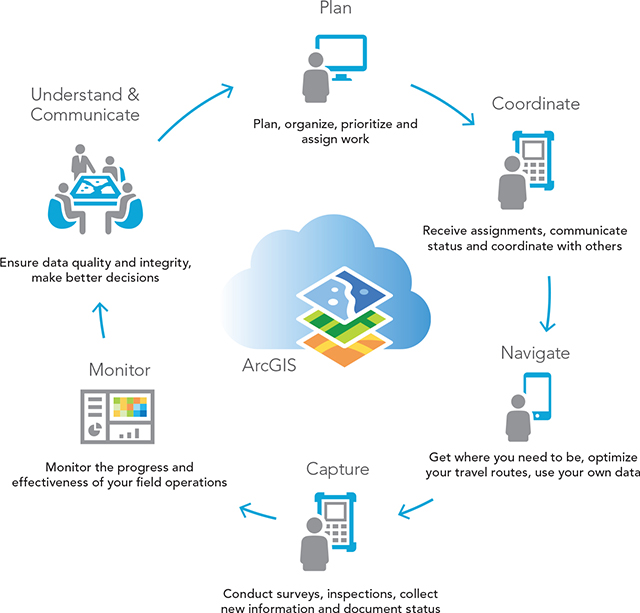

In previous chapters, we highlighted the use of remotely sensed data, GPS, and GIS in basemap creation and the delineation of EAs and how they affect the work at the pre-enumeration stage. This chapter will focus on the combination of the various geospatial tools during the fieldwork of the enumeration phase, including how to rely on the geospatial database to provide the enumerators with the mapping tools they need to conduct the actual enumeration operation. We will specifically highlight the use of the handheld electronic devices for data collection, workforce management, and how geospatial technologies contribute efficiently to the organizational operations and management of the census enumeration.1

Field data verification and quality checks

GIS is used during the pre-enumeration stage (including fieldwork) to build the most complete and accurate delineation of administrative and EA units, and produce the best possible quality EA maps for use during enumeration. As discussed in previous chapters, the digitally created EA map is the result of the integration of data from existing maps (or basemaps) and/or from imagery, complemented by data captured from the field. All this data is structured and organized in the geospatial database. While the EA data is generally accurate, it must mesh with other data (e.g., topographic, built environment, transportation) and then be integrated into the database. This requires final quality checks and verification.

For example, some country experiences have shown that, in the lapse of time between the initiation of GIS-based census work and the time of production of EA maps, some changes to administrative boundaries may have occurred, new buildings may have been built, or some other buildings may have been destroyed. Even when there are instructions to freeze any changes in the last year before conducting the census, there will inevitably be last-minute changes. This means a final verification is required, including consultations with local administrators about any recent changes in their regions.

To do the field verification needed, apps such as Collector for ArcGIS can again be used to collect and update information in the field (whether connected or disconnected). Collector for ArcGIS can be used to collect attribute data as well as capture or edit features. By leveraging the editing function, field-workers can be provided with the ability to edit and suggest changes, plot location of new buildings, or capture POIs not showing on the existing basemap.

Updating EA maps

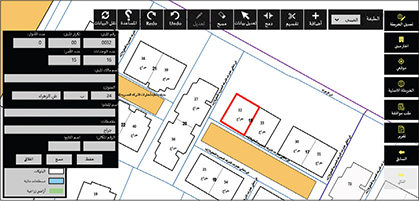

Once the field data verification and quality checks have been carried out, the focus should be on editing and correcting the content of the EA maps as a final step for their design and distribution. Tools such as version control should be used throughout this process to ensure data quality. ArcGIS allows you to set the access level of a version to protect it from being edited or viewed by users other than the version owner or those allowed to edit. It also provides tools that allow for the reconciliation of versions after field-workers have synchronized edits made to versioned data.

For example, a field-worker using Collector for ArcGIS may be tasked to confirm edits from EA maps. The worker goes to the field and collects new data or edits existing features. Once back in the office, the worker synchronizes edits made in the field.

Supervisors or others given permission to accept changes (such as editors) can then conduct QA review. Editors can reconcile with the default geodatabase version and post edits to the default version. (This process can be automated, as well.)

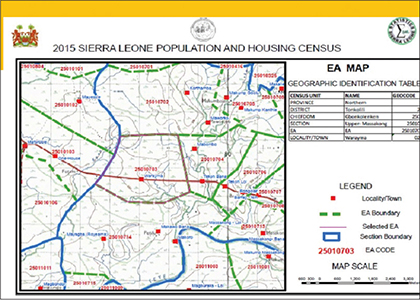

EA map production, map services, and map packages

At this stage, after the completion of the updates and corrections of the EAs and quality assurance checks for all the maps, office work proceeds with the final enumeration map production and printing. The traditional paper-based approach requires a massive production of hard-copy maps in different scales that meet the needs of the enumerators, field supervisors, regional managers, and other staff involved in the census enumeration. Experiences from countries have shown that at least one map must be produced for every EA in the country, with two copies to be printed: one copy to be used by the enumerator and the other by the field supervisor for training and reference purposes.2

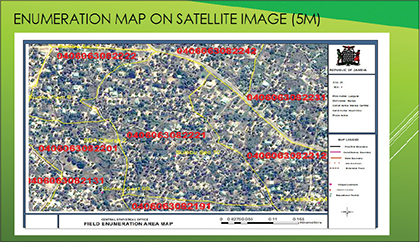

However, the use of geospatial technology in the enumeration process in a CAPI mode is distinguished from the traditional paper-based approach in terms of the reduction in hard-copy map production. In a digital census, once all map data has been verified and EA boundaries signed off, the creation of maps, map services, and printed maps can begin. Digital maps offer better functionality for the enumerator and supervisors—having a detailed basemap available online or offline, in color, and with well-presented features. Digital basemaps also make knowing the location of features and POIs easier and more readily understood compared with hard-copy maps.

All EA maps—whether digital or paper—should be simple, clear, and easy for the enumerator and field supervisor to use. EA maps typically contain the following:

•Basemap with streets and roads, buildings, major water bodies, topographic and other hydrologic features, and map annotations

•EA boundaries

•POIs for orientation with symbols (e.g., church, school, hospital)

Many countries may not be fully digital in their data collection. For those that use multimode methods (paper-and-pencil interviewing [PAPI] and CAPI), they must create both printed maps for PAPI and map services and map packages for CAPI.

Printing maps involves considering such decisions as color or black and white, map size, map scale, the need for inset maps, the use of QR codes or bar codes, and the creation of digital map files in easy-to-print formats as backups for the field and regional offices (including .pdf).

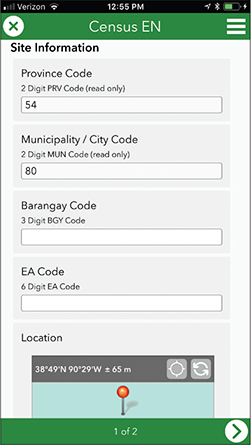

If countries use CAPI, they must rely on map services and mobile map packages more so than printed maps. Today, geospatial technology allows field-workers to use maps and imagery as basemaps in a web GIS approach, allowing the field-worker to collect data and transmit it back to the regional or central office in near real time. For example, mobile apps such as Survey123 for ArcGIS® can be configured to enable a user to download map areas where connectivity is available, show the user’s GPS location, and, with a simple tap on the feature (dwelling or housing unit), add information about the location and accurately capture statistical data about a household, completing the electronic questionnaire related to that household. The enumerator then transmits the data collected online, feeding it directly into the GIS, or saves it until he or she is back within connectivity range for sending to the central office.

As mentioned previously, maps can be used in both online and off-line modes. By creating mobile map packages and downloading these to the device when connected, users simply continue their work in the same manner whether connected or not. The collected data should be uploaded as soon as possible once back in range because progress reports are based on data gathered at the central server. We will elaborate further on the use of handheld devices in the next section.

During enumeration, the EAs may still need additional updates and corrections that must be brought to the master database. Traditionally, the census cartographic staff would collect the paper EA maps after the census and incorporate the edits into the master database; this task can be tedious and sometimes affect the time of the census results. But with the digital approach of the enumeration, this operation can be automated if an app is used with field edits captured for QA. Updates captured in this manner can be verified and then submitted to the database in a more streamlined fashion.

Figure 7.1. Example of an EA map of Sierra Leone. Source: United Nations Regional Workshop on the 2020 World Program on Population and Housing Censuses: International Standards and Contemporary Technologies, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2017.

Figure 7.2. Example of an EA map overlaid on satellite imagery of the Republic of Zambia. Source: United Nations.

Figure 7.3. Example of an EA map from a device in the field. Source: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), Egypt.

Field data collection

Mobile devices and apps

Traditional paper-based methods of census data collection have proven to be tedious, time-consuming, costly, and often prone to errors. To overcome these problems, CAPI methods are increasingly replacing pen-and-paper methods (such as PAPI) as a viable alternative for census data collection. The technological developments in mobile computing, storage, higher connectivity, and network coverage have made the CAPI approach possible for many. Increasingly powerful handheld devices are now an affordable and realistic option, so the CAPI approach is more commonly used. Realizing the advantages of directly entering digital data into a computer software application at the point of data collection using mobile technology for data collection and statistical production, the UN has recommended its use in the 2020 Round of Censuses3 in recognition of its importance and usefulness for many countries.4

Handheld electronic devices have been used by NSOs for many years for the collection of statistical data, initially for surveys and increasingly for census operations. Basically, a handheld electronic device allows for census data to be captured and stored electronically. The contents of the census (questionnaire) form are stored on the handheld device so that the questions appear sequentially on the screen. The enumerator then enters the answers in different ways: with a selection from the offered list of answers or from a classification in hierarchical order presented in the form of a drop-down list; or by entering a variable via a free-form text field, attachment of a photo, or even a scan of a bar code.

In operational terms, the app will not allow the enumerator to skip a question or move from an incomplete answer to another question unless the former has been completed. This ensures that all questions are completed and avoids the lack of answers due to forgetfulness or mistake by the enumerator, which occurs frequently with the traditional paper method.

In addition, building automatic skips and logic into the questionnaire allows the enumerator to avoid covering unnecessary items and ensure increased accuracy. Further, the electronic questionnaire can be designed so that the enumerator conducts minimal data entry as some administrative data can be used to prepopulate fields in the census forms in the office, significantly reducing time needed to complete the form, reducing data errors, and improving accuracy.5

Moreover, data is recorded against predetermined validation rules, and procedures for instant data verification are programmed into the app so that a warning is activated if any data is inconsistent with the format or with other responses already entered in the app. The fact that the app warns the operator when there is an error means that the data can be immediately verified and evaluated by the enumerator, allowing him or her to look for more accurate data while still on location at the time of the interview with the household. In addition, the app cannot accept codes or answers beyond the logical and acceptable norms, thereby decreasing data recognition errors and improving the quality of the data. Another useful feature allows the provision of on-screen help for the enumerators. A help system can make it easier for the enumerators to access definitions or other items needing clarification during the interview. Unlike in a paper manual, the help feature in an electronic questionnaire is more flexible because it can be linked to each question or a term that often needs clarification.

As mentioned in chapter 6, another feature that can provide substantial aid to the CAPI enumeration process is to upload the EA maps onto the device. This allows the enumerators to visualize the EA maps, helping them in their field orientation to find the correct housing units within their assigned EAs. Use of the EA maps and the electronic questionnaires filled out by enumerators, along with GPS points collected on the device, allow the NSO to verify the collected data and confirm whether the EAs were fully covered. Ideally, once the data is transmitted to the central data center, the data including geocodes would be synced with the GIS census database, providing information about the progress of the census coverage.

This highlights another benefit of using handheld devices and configurable apps in the field: being able to report on enumerated units (cumulative) in real time. By using real-time data and operational dashboards, census operations managers can observe, measure, and monitor the progress of the work as well as the remaining time needed for enumeration of each separate enumeration unit. Regularly uploading the data from a handheld device and transmitting it in near real time to the server can also minimize the need to re-enumerate an area if the device suddenly is lost or begins malfunctioning.

Esri’s CAPI tool: Survey123 for ArcGIS

Census survey questions are one of the most powerful ways of gathering information for making decisions and taking action. Survey123 for ArcGIS is a simple and intuitive form-centric data-gathering solution that makes creating, sharing, and analyzing surveys possible with the ArcGIS platform.

A versatile data-gathering tool, Survey123 for ArcGIS makes collecting data in the field straightforward. After a survey is configured in Survey123, downloading and using it in the Survey123 field app is a matter of a few steps. Data captured in Survey123 for ArcGIS is immediately available in the ArcGIS platform. This data can be used to optimize field operations, understand data or data gaps (areas with missing or underreported data) to communicate and make adjustments in the collection, and communicate and share work with others. Survey123 allows data capture anytime and anywhere because it works across devices as a native app and in a browser (online and off-line). The user-friendly intuitive interface also means that training field staff is made simpler.

Figure 7.4. Survey123 for ArcGIS on a handheld device.

In summary, what distinguishes the handheld digital approach from the paper-based one is its integrated data collection process, in which data collection, entering, coding, and editing are carried out simultaneously and automatically. The process is also more efficient and cost-effective overall in the census process when taking into consideration the true total cost of ownership of paper methods. Several country experiences have shown that this method of capturing and processing census data is faster, leading to timely availability of census information results.6 Generally, when using handheld devices, NSOs will significantly automate the whole process of data collection by having a centralized data center (often with regional data centers and even possibly local ones for some large countries) where the data collected and transmitted by each handheld device would be compiled automatically. The data center would also enable the supervisors of the census collection process to make real-time checks into the data collected to verify that the data collected is relevant and correct.

In response to many African countries that expressed their interest in the use of mobile technology for data collection, UNECA has developed guidelines on the use of mobile devices for census data collection and dissemination. The guidelines outlined the main features for selecting a desirable mobile device in terms of hardware and software (see the table) and detailed the key criteria for selecting a mobile device.

Feature |

Description |

Affordability: price of the device |

•License/subscription cost or purchase fees •Maintenance fees •Annual/monthly renewal fees |

Interface |

•User interfaces, color, resolution, keyboard, screen |

Battery life and management |

•Length of battery life |

OS support and updates |

•What type of operating system is used? (Android®, iOS®) •How often is the OS updated with bug releases and features? |

Customizability |

•Can the device be customized, including shortcuts, color schemes, keyboards, etc.? |

Storage/memory |

•Storage capacity |

Peripheral (or APP) support |

•The ecosystem of peripherals or apps (GPS, camera, etc.) |

Multiple-language support |

•Local language support |

Interoperability and connectivity |

•Exchange of data directly or through a network •Cellular mode •Wi-Fi mode •Bluetooth capable |

Security |

•Hardware security (manual lock) •Supports data encryption •Biometrics |

Figure 7.5. Mobile device considerations for data collection (originally from Economic Commission for Africa [ECA] and adapted for current requirements).

Technology is constantly evolving, and computer technology is becoming more portable and more powerful, making the tablet computer affordable and suitable for data collection in the field. Tablets, being computers, do what other personal computers do but lack some I/O capabilities that others have. Tablet computers vary in size, ranging from around 5 inches to 12 inches depending on the model7 and are available in a variety of forms: the main slate tablets don’t come with a physical keyboard, while the hybrid tablets come with a detachable keyboard or an integrated one (convertible).

While available connectivity varies by model, most tablets include Wi-Fi connectivity, and many can also access the Internet over-the-air using a service provider subscription. A tablet’s touch interface makes some common tasks more intuitive, and the device provides easy web browsing and navigation in many applications. Tablet computers, like standard computers, are powered by different operating systems. Three operating systems prevail currently in the tablet world: Android (Google®), iOS (Apple®) and Windows® (Microsoft®),8 though the Amazon Fire Tablet® (with custom Android OS) is also gaining traction.

The compact design of tablet PCs makes them suitable for fieldwork; they are easy to use, lightweight, and portable.

Smartphones are also making a big impact in field data collection. With rapid changes in technology, smartphones today can do many things that would have required a personal computer just a few years ago.

A smartphone is a handheld personal computer with a mobile operating system and an integrated mobile broadband cellular network connection for voice, short message service (SMS), and Internet data communication. Most if not all smartphones also support Wi-Fi. Smartphones are typically pocket-sized, as opposed to tablet computers, which are much larger. For fieldwork, smartphones and tablets each have their own advantages and disadvantages. Both can capture, store, and transmit data, but they have distinct differences in price, features, and functionality.

Figure 7.6. Dell® Rugged device.

One of the most important options that contributed to the adoption of handheld electronic devices for census data collection is the built-in GPS receiver. A GPS receiver integrated into the handheld device allows enumerators to understand their current location and capture the geographic location of where census data is being collected. GPS data also allows local supervisors and/or those at the NSO to track the enumerators and check whether the capture of the data was performed at the right place in the household, avoiding false data entry. In addition, captured GPS locations can be used as a reference point for other post-enumeration activities. Since many handheld devices are designed as consumer items, the built-in GPS receiver may vary greatly in locational accuracy (1 to 5+ m) to capture the latitude and longitude of each housing unit or building. Therefore, NSOs should inquire about the accuracy and proceed with field tests in both urban and rural areas.9 If greater locational accuracy is needed, you can pair with third-party external GPS receivers that connect to the smartphone via Bluetooth.

No matter what type of device is chosen, security must be a consideration. If a device is lost or stolen, procedures need to be in place to make sure that data privacy is secured. No single type of security will ensure the prevention of data tampering or theft. Multiple levels of security should be considered, including hardware security, application-level security, data encryption, and data transfer security protocols. For more information on mobile security and GIS, see the Esri white paper on mobile security (ArcGIS Secure Mobile Implementation Patterns) in the online ancillaries at esri.com/Census2020.

The benefits of using handheld devices lie in their ability to provide consistency and validity checks during the interview of the households, facilitating the control of the enumerators’ work—for example, by checking that the coordinates captured by the GPS correspond to the assigned EA and transmitting the data collected in real time or near real time to the data center. Paradata from the device can also be used to validate, using date and time stamps for the start and stop of a survey—for example, as a key indicator of accuracy and to help prevent fraudulent entry.

Figure 7.7. Bad Elf® GNSS Surveyor, which offers submeter accuracy.

Even though the benefits of mobile data collection are many and are leading to its adoption by numerous countries10 with many more planning for its adoption in the ongoing 2020 Round of Censuses, its use will present some challenges that the NSO may be unfamiliar with and should consider, including the following:

1.Consideration should be given to the configuration and use of the devices. Planning for the use of mobile devices should be considered in all parts of the business process, testing will need to be conducted, training plans will need to include device training, and the loading of data and applications should also be understood and planned for.

2.When designing the digital questionnaire, consider the mode or modes of use. In a multimode survey, a digital version may vary slightly from a paper version, which doesn’t allow for skips in the same manner.

3.This approach also requires the consideration of the field operations and support necessary during enumeration, including provisioning and field support and connectivity for the devices. The mobile data collection process is an integrated approach that requires the following:

a.Device—A device manufacturer is required to provide the devices as per specifications, or an agreement with a connectivity provider on a hardware lease program.

b.Connectivity—A wireless carrier or connectivity provider is needed to provide service for the device so that the data can be transferred seamlessly to the data center.

c.Applications—Consider the applications that are needed on the device beyond just the basic data collection applications. Email, calendar, or other productivity applications, navigation applications, and security applications all need to be understood.

d.Capacity building—An important component requiring the enumerators to be trained on using the survey app and forms on the device, the entire process of data collection, the basics of the device, and troubleshooting.

4.The use of the device in the field requires that the battery life and the practicalities of charging the device be tested and checked because failure in the field would also cause support issues (e.g., if the battery lasts less than needed, a portable charger, solar charger, or some type of battery extender may be required).

5.Testing the download process and data transmission speeds should be conducted. This testing may identify parts of the system that require scaling to accommodate any expected peak or heavy loads. This should also include the testing of security protocols.

6.If the unit is lost or stolen, precautions should be in place to transfer data from the device and remotely wipe the device.

Case study: Jordan

In 2015, Jordon took a geospatial digital approach to its census, and the outcomes were astounding. The kingdom’s Department of Statistics (DOS) reduced a two-year-long process to just two months, improving data accuracy, speeding the delivery of vital data to stakeholders, and safeguarding millions of records of sensitive personal information.

Every ten years, the DOS gathers census data to formulate and improve diverse national programs such as economic development, agriculture, and healthcare. The government welcomed the modernization of its census processes and hoped that doing so would produce accurate and up-to-date statistical data and information. Census data is an important and essential tool for making evidence-based decisions and intelligent planning. Furthermore, the 2015 census project represented a major step forward in Jordan’s digital transformation that would move it closer to its vision of becoming a regional technology hub.

The DOS was faced with the challenge of running a census at a national level for the first time and using a digital system to do it. By the time the DOS completed the Population and Housing Census 2015, it had collected census data for 9.5 million citizens. More than twenty thousand surveyors had participated in the largest statistical project in the kingdom’s history.

How did they do it? In the digital world, all projects begin with data. The DOS needed good data to set the data groundwork for a well-run enumeration operation. In cooperation with governmental agencies and local private companies, the department procured aerial images and created a current and accurate basemap. Using GIS, it digitized census blocks and created data layers that delineated collection areas on a map.

The department acquired more than twenty-three thousand high-spec HP tablets that enumerators would use to capture survey data. Staff prepared the tablets with aerial imagery, census blocks, building points, routes, and the survey form. They also synchronized the tablets with the operation’s server and added census applications to them.

The census application’s rules-based workflow ensured that the correct questions were asked, no questions would be missed, and correct data was collected. Survey data was not stored on the tablets but synced back to the server. The application communicated with a central server in Amman via the tablet’s 3G communications. Thus, the system could cross-check the validity of information in real time during the survey.

In previous censuses, fraud was a concern, including the altering of data before it was reported. To address the problem, administrators devised another workflow for data security. Once surveyors left their assigned areas, the application suspended access to the system by the surveyor. Furthermore, automated processes controlled the amount of data feeds emitted by surveyors and stored data in an Oracle® DBMS geodatabase. The method secured data against corruption and manipulation. DOS administrators reported that the digital solution inspired more trust from citizens because it was modern and that they perceived it to be less susceptible to inaccurate reporting.

The DOS usually outsources census field survey labor and hired twenty thousand surveyors and two thousand field managers for the 2015 operation. Because the department had deployed easy-to-use mobile apps, workers needed only a little training before going into the field. Assigning work areas to so many people is a geospatial problem, so, again, GIS proved useful. It defined surveyors and assigned them to designated census blocks, thereby avoiding survey duplication and wasted effort. Other time savers were apps that showed surveyors their assigned work areas along with routes that would help them collect the data in sequence.

The ArcGIS platform made managing data collection a smooth process. It provided census operations managers with tools to control and monitor human resources, material, and time. The approach produced better data quality and turned it around faster than ever before.

Jordan’s census project was further marked by its extensive use of GIS throughout all phases, including operations planning, fieldwork management and monitoring, and data proliferation throughout the kingdom. It also provided an online infrastructure for spatial data dissemination and analysis that included tools for analyzing data about the population’s economic, social, and demographic characteristics.

The ArcGIS platform, the project’s cornerstone software, integrated with Microsoft® Windows 10 and the HP® tablet to enable mobile capabilities. The platform also processed data and disseminated key statistics. The DOS completed its operations in record time and was publishing 2015 census results about three months after the fieldwork had been completed, compared with the 2004 census results that took one and a half years to publish.

Most importantly, e-census data provides analysts and decision makers with a simple, intuitive means to get answers to their inquiries.

Internet

Like with mobile technology, the use of the Internet for census data collection is growing. Considerations for using GIS technology in Internet self-reporting should also be given.

The big difference between mobile data capture and Internet self-reporting is that the Internet-based data collection directly involves the household and requires household members to fill out the census questionnaire online, eliminating the enumerator as an intermediary. The self-response method requires that the household respondent have the necessary equipment and reliable Internet connectivity, with a sufficient level of computer literacy.

Similar to mobile data collection, the online Internet questionnaire or computer-aided web interview (CAWI) is not a simple replication of the paper form. Adjustments are likely to be made to accommodate the respondent with an easy-to-access user-friendly interface. GIS functionality can be included in the web-based form by way of a map presented to users, allowing them to indicate their place of residence. This information can be captured and stored along with the form providing the location component of the survey for validation against preassigned codes or other information.

CAWI data collection relies on self-enumeration and, like other modes, must ensure that every household and individual is counted once and only once. A key factor in managing data collection requires the provision of each respondent with a unique code. This code may be linked to a geographic location (e.g., the “census-assigned unique address identifier” to be used at the 2020 US census). Also, since the CAWI-collected data must be incorporated into the database with other modes of collected data (CAPI/PAPI), census data collection methodology requires careful thought as does the management of the other streams of data, when the census is multimodal.11

Field operations management

Field enumeration operations are often a huge undertaking with a large workforce that can range from hundreds of people to hundreds of thousands of people, depending on the size of the country, the methodology for data collection, and the time frame for its execution. Field operations management presents a big challenge in several areas, including logistics, the movement of assets, the movement of employees and data in the field, employee safety, and data security. One of the benefits of using new technologies (including GIS) is the capability they provide the NSO to streamline and automate field operations and thus improve their management and the quality of the census itself. Field operations require efficient communication among possibly thousands of field-workers, field supervisors, and census managers, as well as the constant monitoring of a large variety of logistical items and materials, most of which must be distributed to field offices in all regions of the country and then recollected. Achieving productivity in the field depends particularly on the NSO’s ability to share information that’s accurate and up-to-date.

The key concern is the flow of timely information to and from the field. Mobile technology provides the real-time bidirectional flow of information between census managers in the back office and enumerators in the field. Bidirectional workflows allow the census managers to be informed of the progress of the data collection operations while providing the enumerators with updates, including which households need follow-up. Furthermore, with GPS-enabled handheld devices, census managers can locate and track the location of the enumerator (in real time or near real time) or identify areas of gaps where enumeration is falling behind or not meeting quality standards. This triggers urgent attention to be given to the affected EAs for appropriate decisions to remedy the situation. In this manner, GIS systems provide for better engagement and needed transparency across all levels of management and field-workers.

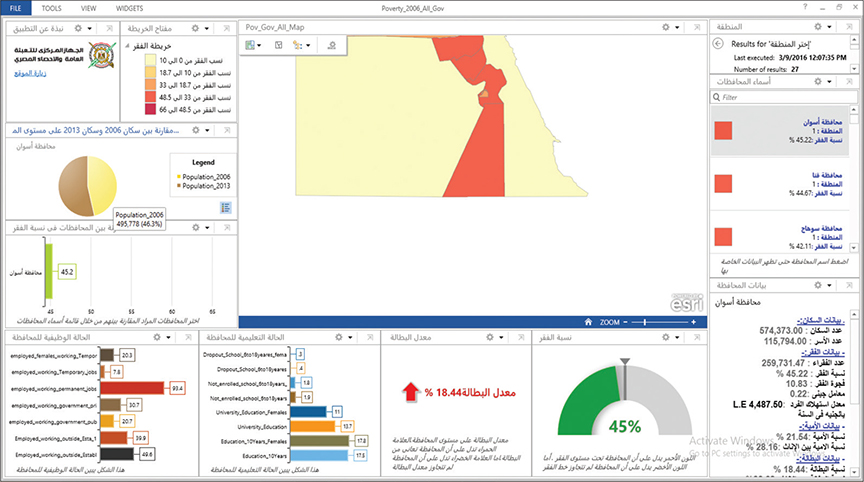

Operational dashboards can also be used to provide a view of geographic information that helps you monitor events or activities. Dashboards are designed to display multiple visualizations that work together on a single screen. They offer a comprehensive and engaging view of data to provide key insight for at-a-glance decision-making. From a dynamic dashboard, supervisors can view the activities and key performance indicators most vital to meeting objectives.

Figure 7.8. Field operations workflows.

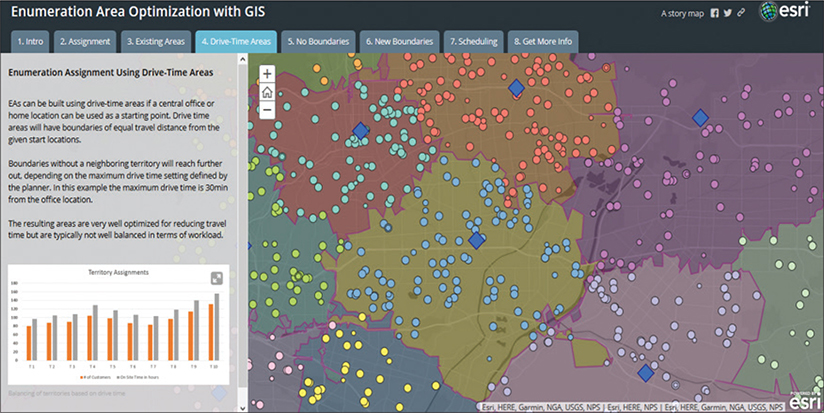

Optimizing workloads

Another management activity is the assignment of workloads to the enumerators. GIS-based analysis of the EAs helps optimize the workload assignment. Since the master EA database or plan is centralized and available on the same system, the GIS manager and the staff in charge of the census organization have a complete view of the distribution of the EAs and supervisory maps in the field. The geographic database helps in the assignment of administrative units to operational areas and, as we saw earlier, in the location of field offices.

For each field office, the map compiled from EA maps for use by the supervisors allows the manager to know exactly who is assigned to which tasks combined with the list of tasks to be executed. It also, importantly, allows the field manager to estimate the optimal workforce needed and to optimize the workloads and potential travel needed to cover the area the field office oversees. This includes the optimal scheduling of fieldwork (see figure 7.10). Optimization is essential to avoid field teams having to drive unnecessary distances between operational areas; avoiding duplication of effort where the same operational area is allocated to two teams or multiple enumerators (e.g., gated community with limited time constraints); allocating and delivering the right number of handheld devices and appropriate logistical material to the teams of enumerators; and obtaining status reports from the field and office.

Figure 7.9. Supervisor dashboard from the Philippine Statistics Authority.

In addition to the provision of digital maps for use in the field, GIS allows us to use apps such as Workforce for ArcGIS® that help efficiently manage field operations. Sometimes, the unexpected can happen: a trained enumerator may get sick or quit, and reassignments must be made. Workforce for ArcGIS enables a common view of the workload in the field and the office. It enables managers to assign tasks and make sure the count stays on track. By using a web-based app in the office, managers can create and assign work to mobile workers, who use the mobile app to receive and work through their list of new assignments.

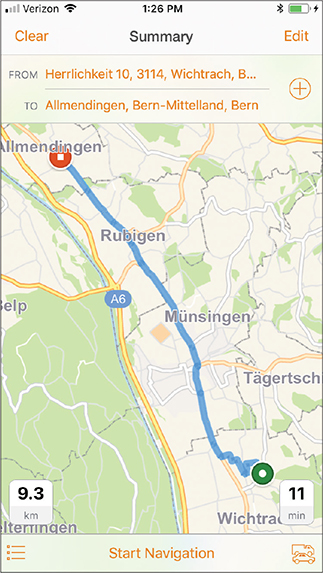

Optimizing routes

Once the assignment of the workloads has been made and fieldwork is ready to begin, the teams of enumerators need to know where to go and ideally the best route to take. GIS provides tools for solving complex routing problems and can be used to create suggested routes for the workers. These tools allow us to solve for variations in schedule, such as days of the week, time of day, or even the skill set in workers (e.g., language skills). Once the routes are generated, they can be shared with workers via the mobile device. If a navigable dataset is not available for the area, workers can simply use built-in maps on the device as a visual guide along with GPS coordinates of the locations (households) to be enumerated.

Figure 7.10. Optimization of EAs with GIS. The map shows drive-time calculations from the central office location.

Figure 7.11. Workforce for ArcGIS app on a mobile device.

Figure 7.12. Route optimization and navigation.

Optimizing routes to enumeration sites in urban areas will usually not be a problem because the road network is generally well-defined. Optimization can be difficult in rural and remote areas where the road networks are less demarcated and perhaps data is not available for routing.

GIS-based mobile apps are increasingly available to cope with specific navigation or routing problems. For example, Navigator for ArcGIS®, a mobile app that gets the field workforce where it needs to be, works in online and off-line mode on any device. Navigator for ArcGIS even allows field crews to navigate vehicles on their organization’s custom data and street network. Crews can also search by asset ID or location and easily plan their day by creating a work list of all their stops.

Monitoring the progress of census operations

Mobile technology has the advantage of being able to feed in real time (or near real time) data collected from each device to the central database. This data can also be used to monitor the progress of the enumeration and identify which households the enumerators may need to revisit. As explained earlier in the chapter, workload assignments and the navigation and optimization of routes happens on the same system, so the GIS manager not only knows exactly who is doing what at any moment but also more importantly can monitor the overall status and progress of each stage of the census operations. GIS dashboards can display supervisory maps combined with work assignments and schedules and can track the progress of completed work.

Monitoring the progress of census operations, from supervisors through the regional census offices and on to the central office, allows managers to assess where operations are running smoothly and where problems may be encountered. With the traditional approach, these assessments are compiled in tabular form and would take time to provide a clear idea of the progress and to review and proceed with any follow-up. But with the use of geospatial and mobile technologies, census managers can be informed of the progress of the collection operations as the enumerators deliver and collect completed census forms. The assessments of the situation and the progress can then be visualized geographically through a dashboard. This allows census managers to review the situation in near real time, identify areas where the enumeration is not progressing as expected, and provide the enumerators and their supervisors with appropriate updates and instructions on the households to be followed up.12

Figure 7.13. Operational dashboard, CAPMAS Egypt.

Project management oversight and identifying trouble spots

Project management oversight is generally conducted and based on management standards, policies, processes, and methods to ensure that a project has been carried out on time, within scope, and on budget. The oversight ensures that the risks threatening the project have been identified and mitigated. This model of management oversight applies to the census field operations. As we have seen earlier, the use of GIS and mobile technology supports the management of field operations, including the optimization of workloads, routes and navigation, and monitoring of the enumeration progress. Streamlined field management using automation and technological tools has the advantage of rapidly producing performance metrics associated with field operations, which can then be used to measure whether tasks have been carried out on time, the rate of coverage is within expectations, and the cost estimates are within the budget allocated.

The geographic approach to these field operations with the use of GIS- and GPS-enabled handheld devices also has an important risk management advantage in terms of the identification of trouble spots and the solution brought to mitigate their effects, including adequate and timely feedback to enumerators so that they can update their own collection control information and arrangements of visits by office personnel to field locations. Since the handheld devices are integrated into the central census database, alerts may be sent to the field staff or supervisors—for example, when the monitoring system detects that “coverage is lower than expected.”13

Based on good practices from the 2010 Round of Censuses and recent country experiences, studies, and reviews, there is general recognition that the use of geospatial information technology offers integrated systems for field management that have a positive impact on the management of the field operations, including the reduction of costs and improvements in the quality of the data collected, provided that some arrangements are taken into consideration. As stated previously, those arrangements include the early planning of their use, the existence of reliable telecommunication and connectivity infrastructures, testing, and trainings. GIS can provide both operational dashboards to see the status of the project and survey dashboards to see the status of the work. Supervisors can use these dashboards to spot-check data collection activities and to ensure the survey sample size is being met as expected.

Location-based apps used during the enumeration process can create improved workflows to replace repetitive and outdated stand-alone fieldwork processes; make data available across the NSO so that operations run more smoothly; and monitor field activities accurately to improve reliability, consistency, and create transparency.

Figure 7.14. Survey123 for ArcGIS dashboard.

US Census: Mobilizing field operations

[The Former Chief Geospatial Scientist Tim] Trainor thinks the Census Bureau will save the most money by infusing its field operations with more GIS and mobile technology.

Although the census has a 65–67 percent response rate, which is exceptionally high, the Census Bureau still has to get the rest. And nonrespondents live across the United States, so this ends up being a huge field operation that must be completed in a short amount of time.

In the past, this has required hiring hundreds of thousands of temporary staff to go door-to-door to find the people who didn’t fill out the census and convince them to do so. All these employees had supervisors as well to introduce them to their assignments and oversee each portion of the larger operation.

“We used mobile technology in 2010, but it was basically to ensure that we had complete coverage and to give folks an idea of where they were,” said Trainor. “There was no navigation capability.”

For the 2020 census, however, the Census Bureau is looking to expand its use of mobile technology and incorporate navigation and workload management into it.

“When we hire [these temporary staff members], we geocode them to their location . . . to give them assignments close to where they live so we don’t have people traveling [farther] than they need to,” said Trainor. “It’s also an opportunity for us to manage whether or not we have enough people in a given area to do the work, which has always been one of our greatest concerns.”

The Census Bureau also wants to use mobile technology to provide field employees with short, portable training segments.

“We’re very good at making manuals, and we’ve made hundreds of pages of training manuals that some people read and others don’t,” said Trainor. “But we’re moving away from that and trying to make it as easy as possible for people to understand . . . how to do their jobs”—ideally allowing them to refer back to their training materials while they’re out in the field by using their mobile devices.

This will let the Census Bureau significantly reduce its field infrastructure and supervisory setup.

“This time around, we’ll have six regional census centers and approximately 300 local census offices,” estimated Trainor.

That’s a 50 percent cutback in regional management and a 40 percent reduction in on-the-ground labor.

A more seamless census

The US Census Bureau is hoping that its increased use of GIS and other technologies will lead to a safe and easy 2020 Census and bring expenses down to 2010 levels.

“We’re estimating we’ll be in the neighborhood of a $5 billion savings,” said Trainor.

Not only that, but by digitizing many operations and using GIS more pervasively throughout the census cycle, the Census Bureau anticipates a more efficient, seamless enumeration on census day, April 1, 2020. States across the country will certainly appreciate this, since they only have a few months after the first part of the census data is released in early 2021 to redistrict their jurisdictions for elections later that year.

Extract from ArcNews “2020 [US] census embraces digital transformation.” Fall 2016. Available at http://www.esri.com/esri-news/arcnews/fall16articles/2020-census-embraces-digital-transformation.

Case study: Arab Republic of Egypt

The Egypt 2017 national census for population, housing, and facilities is the country’s first census completed electronically. The transformation from a paper to a digital census system enables Egyptians to see census data in a geographic context. Moreover, the modernization of the process introduces technology that is a gateway to information at a greater depth and scale than ever before.

Understanding the country’s data strengthens the Egyptian government’s ability to monitor social trends and mitigate disaster. Egypt’s statistical office—the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS)—implemented an enterprise GIS platform so that government, industry, and the private sector can easily access and analyze data. The central technology for disseminating census data is the CAPMAS geospatial portal Egy-GeoInfo, which gives officials and citizens alike access to the nation’s statistics.

Project planning

To plan the project, CAPMAS worked with the H.E. minister of planning and the World Food Programme (WFP) to evaluate the system’s business goals and anticipate user requirements. The partners worked with a team of economists and statisticians to determine how people could use geospatial national statistics for investment, economic development, building policies, and so forth. They also took into consideration the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for Egypt 2030.

CAPMAS, which was responsible for executing the plan, called on Esri to provide the GIS platform and technical direction. WFP offered technical support and its international knowledge of best practices to guide the system’s design. The partners carefully considered all aspects of census activities and determined if and how GIS could support them.

Data planning

The 2017 census plan included bringing all statistical data into a geospatial database. The team implemented a new geospatial database repository for organizing geospatial and nongeospatial data. It also added big-data management capabilities to the system. The 2017 census geodatabase now manages one-half billion records.

The team knew that data is more valuable if it can be harmonized with other data. Therefore, the team specified that data be open so that it can be used by other organizations and systems. The metadata would include time and GPS location. They also devised a strategy for keeping data updated.

Enumeration planning

To train surveyors, CAPMAS developed agile-training activities for everyone from top management to enumerators. It also developed a faster training course to get new recruits up to speed if they joined the enumeration after it started. Training was included in the census budget.

The 2017 e-census covers more than ninety million capita over approximately one million square kilometers. Administrators used GIS to monitor forty thousand enumerators and synchronize forty thousand tablets. CAPMAS created high-quality maps for surveying activities and made live updates to them reflecting field data collection. The system updated digital maps for all urban and rural areas in Egypt.

Dissemination planning

CAPMAS set goals for census data distribution. The dissemination mechanism had to be built on a decision support system. The system needed to be easy to use and easy to update. Also, the data needed to be anonymous. The ArcGIS platform’s portal technology met these requirements, and CAPMAS used it to build the Egyptian Geospatial Information Portal, or Egy-GeoInfo.

Egy-GeoInfo (geoportal.capmas.gov.eg) provides transparency to census data by allowing citizens to see all census and other statistics produced by the national official statistical system. The secure system aggregates data to the village level but does not disclose statistical information at the address level. People needing the most updated statistics, from high-level decision makers to common Egyptian citizens, can use it. In addition, Egy-GeoInfo provides the evidence-based regional info-structure to monitor and evaluate Egypt Vision 2030 activities for meeting the country’s SDGs.

The portal accesses cross-discipline information that expands the system’s research capabilities. In addition, geoanalytic tools help users manage much of their own research. For instance, they can see clusters of unemployment, trends for home ownership, and education levels by area. They can also see population growth over time and analyze changes in population patterns and location. Because the data is on the ArcGIS platform, decision-makers can combine different statistics, such as income levels and education, to research sales and investment potential.

From planning to execution to dissemination, Egypt completed the digital census project in four years. It now has the foundation to complete other statistic projects that will move the country toward meeting its sustainability goals. Egy-GeoInfo is an award-winning technology and has been highlighted at the UN GIS conference. It also received a smart government award for the best Arab smart application.

References

•A. E. Anderson and A.J. Tancreto. 2011. “Issues, Challenges and Experiences of the Internet as a Data Collection Mode at the US Census Bureau.” Paper presented at the International Statistical Institute (ISI), Dublin, Ireland.

•UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division. 2009. Census Data Capture Methodology: Technical Report.

•UN. 2009. Handbook on Geospatial Infrastructure in Support of Census Activities.

•UN Statistics Division. 2010. Report on the Results of a Survey on Census Methods Used by Countries in the 2010 Census Round.

•Zelia Bianchini. 2011. “The 2010 Brazilian Population Census: Innovations and Impacts in Data Collection.” Paper presented at the 58th World Congress of the International Statistical Institute (ISI), Dublin, Ireland.

Notes

1.According to the UNSD’s Report on the Results of a Survey on Census Methods Used by Countries in the 2010 Census Round of Censuses, 102 of the 138 countries, representing about 74 percent of the responding countries, reported employing GIS/GPS technology. This report is available at http://unstats.un.org/unsd/census2010.htm.

2.See the UNSD’s Handbook on the Management of Population and Housing Censuses, rev. 2. Available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesF/Series_F83Rev2en.pdf.

3.The UN has recognized the following:

a.Availability of wide range of geospatial technological tools for use in census mapping

b.Enablers for NSOs to collect more accurate and timely information about their populations

c.Use and application of geospatial technologies are very beneficial to improve quality of census activities at all stages of census

d.Satellite images

e.Aerial photography

f.GPS

g.Georeferenced address registry

h.GIS for enumeration maps and for dissemination

i.Adoption of GIS should be a major strategic decision

j.A census GIS database is an important infrastructure to manage, analyze, and disseminate census data

k.Geospatial analysis must become a core competence in any census office

l.Statistical offices should develop GIS applications with population data and other georeferenced data from other sources for more advanced forms of spatial analysis

m.Use of interactive tools

n.Mapping functionality

4.See Principles and Recommendations, rev. 3. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/67/Rev.3. Available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/Standards-and-Methods/files/Principles_and_Recommendations/Population-and-Housing-Censuses/Series_M67rev3-E.pdf.

5.See the UNSD’s Census Data Capture Methodology Technical Report. Available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/census/documents/CensusDataCaptureMethodology.pdf.

6.For example, Egypt used mobile devices for its 2017 census data collection, improving the timeliness of census releases—releasing data in a few short weeks instead of more than one year for previous censuses. Source: CAPMAS presentation at Esri UC 2018 “MRamadan Geo-SoOSs-2.”

7.Those tablets suitable for census data collection range from 7 to 10 inches, which allows for the optimized size, weight, and brightness and holding with one hand, all of which are suitable for fieldwork.

8.Just a few words about pricing: Tablet prices are changing rapidly, ranging in 2017 from dozens of dollars to hundreds of dollars, depending on the type of the tablet.

9.See the US Census Bureau’s “New Technologies in Census Geographic Listing.” Available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2015/demo/new-tech-census-geo.pdf.

10.Ranging from large countries such as Australia, Brazil, Canada, and Egypt to small countries such as UAE and Cape Verde.

11.There were three streams in the case of Singapore, where computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) was another alternative.

12.See Conference of European Statisticians Recommendations for the 2020 Censuses of Population and Housing, ECE/CES/41–2020 Census Recommendations. Available at https://www.unece.org/publications/2020recomm.html.

13.See the UNSD’s Handbook on the Management of Population and Housing Censuses, rev. 2. Available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesF/Series_F83Rev2en.pdf.