I’m waking up for the second morning in my childhood bedroom, which doesn’t feel at all like the bedroom of my childhood. Mom didn’t waste any time repainting and refurnishing once I left for college. She gave away my big-girl wooden desk with a drawer that locked without telling me. My journal and a love letter from Pete Freelander were locked in that. I took the key with me. I still have that key somewhere.

I was 18. A baby. I remember my first call home.

ME: Hi Mom, I’m calling from the payphone in the hallway and there’s a long line of kids waiting for it so I can only talk for a minute.

MOM: They can wait. How are your classes?

ME: Pretty good. The kids here all seem to know what they want to do with their lives. It’s a little intimidating.

MOM: Intimidation can be motivating. Use it to your advantage. Elise, I’m fixing up the apartment. I started in your room and gave your desk to one of the doormen who needed a desk for his daughter.

ME: But it’s my desk.

MOM: You don’t need it. You left.

ME: Going to college is not leaving.

MOM: To me it is.

By the time I got home for Thanksgiving, all that was left of my childhood bedroom were the books on my bookshelf, which all these years later are still here and still smell like high school crushes and bubblegum lip-gloss. A Separate Peace, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Catcher in the Rye, A Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, The Sun Also Rises, The Scarlet Letter, Great Expectations, The Great Gatsby, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Sons and Lovers, Pride and Prejudice, To the Lighthouse, Demian, The Odyssey, Slaughterhouse Five. It is the bookshelf time stopped for. I underlined practically everything. I didn’t want to miss something important, pass over some symbolism that I was surely not understanding, and I put a little star next to every mention of a setting sun or rising moon.

Yesterday Mom and I had breakfast together and I asked her why she gave away my desk.

“You said you didn’t want it anymore,” Mom said. Instead of getting into it with her about the desk, I asked her if she wanted another piece of toast.

She had an appointment scheduled for a haircut, and put on makeup and a velvet shirt, unbuttoned unnecessarily low. I went with her to a tiny salon, barely noticeable when you walk by, just off of Broadway.

Mom introduced me to her haircutter as “a brilliant playwright.” Her haircutter said, “Your mother is a fascinating woman.” Mom returned the compliment, I think, by calling her “the Georgia O’Keeffe of haircutters” and announced to us both that I could use a haircut. So after Mom’s cut, the Georgia O’Keeffe of haircutters snipped, styled, and blew out my hair.

I was elevator ready and had errands to run. Mom needed food. Mom needed toilet paper. Mom needed lightbulbs. Mom needed laundry detergent. In running these errands I managed to get two elevator rides with my handsome elevator friend. We traversed 30 floors together. I’ve ridden elevators with other men but have never felt this kind of intimacy. When I’m with him, I feel us counting the floors together. It feels like foreplay, no, floorplay. We’re standing in the same enclosed space—a step away from spooning. Breathing the same air, practically kissing. I could ride the elevator with this man forever.

I know I should have been writing, not making up excuses to ride the elevator, not hanging out with Alan the doorman for over an hour, but it was nice catching up with him and hearing the latest building gossip. Alan is both incredibly discreet, and a first-rate gossip, which sounds like a contradiction, but for New York doormen it’s not. Gossip is big currency in the city, and New Yorkers pride themselves on the high caliber of their inside information. The city’s doormen are privy to more good gossip than anyone else. But they’re like priests, or shrinks, or bartenders. It’s almost impossible to get anything out of them. The amount of scandalous information they are in possession of is so secure and solid that it’s probably providing additional structural support for the city’s buildings. To break through the sacred covenant between a doorman and his tenants, you have to pretend you’re not gossiping, so conversations go something along the lines of: “Do you know if it’s supposed to rain again tonight?”

“I believe there are supposed to be intermittent downpours, as in the past three nights, but they’ve been stopping by 2:30, around the time Madonna leaves Mr. Handler’s apartment.”

“Okay, good to know, thanks.”

I don’t know why I’ve waited this long to get the lowdown on my elevator crush, and I certainly couldn’t tell Alan why I was interested. I managed to get quite a bit of information without being too revealing, and he seemed happy to gossip, without being too revealing. What I surmise from Alan’s roundabout way of revealing information is that my elevator crush sometimes has boldface name visitors. Mostly musicians. Most notably a Beatle—“There aren’t cockroaches in the building, but there have been beetle sightings.” I wonder if it was Paul or Ringo? I think he works in the music industry, but that was harder to ascertain. I am certain that he’s got three kids, all adults now. And he’s divorced. His wife left him for a Nobel prize-winning scientist. I swear stuff like this only happens in New York. I would have been thrilled if Elliot had left me for someone who won a Nobel prize. A Pulitzer would have been electrifying. If Midge had been awarded a MacArthur Genius Award, I’d be a proud divorcée. Hell, I’d even settle for someone who earned the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. Being left for a genius gives a breakup heft. It’s a breakup that matters. I’d have been totally understanding, even supportive. “Go be with your genius, Elliot,” I would have said. But no, Elliot left me for a phony dullard who talks babytalk to adults. How humiliating.

I suppose the next time we’re in the elevator together I could ask him out for a cup of coffee, but I know I won’t. I hate having the sophistication level of a 12-year-old, and not one of those precocious 12-year-olds that are everywhere these days. And I hate not being able to finish my play. I need to refocus. I can’t get obsessed right now with a luscious-lipped man in an elevator. Once she wakes up, I’ll have breakfast with Mom, then drive back home and get back to work.

(Laurie’s house. LAURIE is slouched at the table eating while reading something on her laptop. GRACE is reading while sitting upright on a corner of the couch. The doorbell rings, followed quickly by a succession of knocks and bangs at the door.)

GRACE

Somebody’s at the front door.

LAURIE

They sure are.

GRACE

I’ll get it.

LAURIE

That’s okay. I’ll get it. You relax, Mom.

GRACE

You’re eating. I’ll get it.

LAURIE

It’s just a snack. I can get it.

GRACE

I’m not an invalid. I can get up and answer the door.

LAURIE

Fine then, you answer the door.

(Laurie goes back to eating and looking at her laptop. Grace puts her book down on a table near her chair and gets up with a loud groan. She walks slower than necessary toward the front door, while the knocking continues.)

LAURIE

Mom, are you okay?

GRACE

I’m still a little sore. That accident should never have happened. It wasn’t my fault, and yet, you insist that I stop driving. What happened was the fault of the auto industry. You should be blaming Detroit for my accident, not me.

LAURIE

I don’t want to blame Detroit. I like Detroit. It’s one of my favorite cities. And even if what you’re saying had a semblance of truth to it, you still shouldn’t be driving. Are you going to answer the door or not?

(Grace opens door the door.)

GRACE

Larry?

(She pushes the door closed. LARRY, standing on the other side of the door, pushes it back open. The door remains open.)

What are you doing here? Laurie, did you invite your father over?

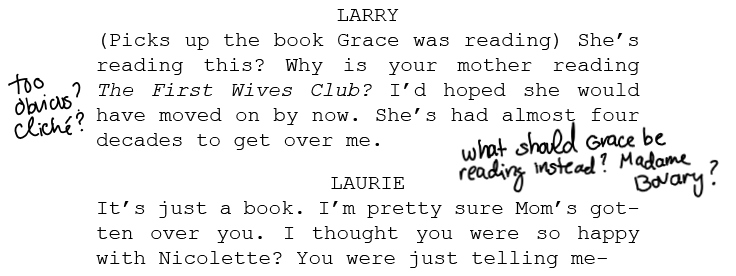

LARRY

How are you, Grace? Don’t answer. I really don’t care. I was driving by and thought I’d stop in to see my daughter. Laurie mentioned to me that you had imposed yourself on her and taken up residence. I see she wasn’t kidding. If you don’t mind, I’d like to speak to my daughter.

GRACE

Don’t you have a phone, Larry? You should call Laurie if you want to talk to her. Laurie is excellent on the phone. She mastered the art of speaking on the phone when she was a teenager. Of course, you weren’t around enough to have known that, but I assure you, she’s a pro. One of the best.

(Grace cranes her neck to look beyond Larry.)

Is that your fancy car out there? I bet that car has its very own phone in it. Why don’t you go back and sit in that nice-looking car and call Laurie. I’ll make sure she picks up. Good-bye, Larry. Have a good call.

(Grace tries to push the door closed. Larry is holding it open. They start pushing and pulling on the door while grunting and groaning, with subtle hints of orgasmic sounds as they scuffle. Laurie listens from the other room, shaking her head. She closes her laptop and walks to the front door. She makes umpire signals for TIMEOUT/FOUL BALL and SAFE while she walks toward them. Then she steps across the threshold and gives Larry a hug.)

LAURIE

Pops, what are you doing here?

GRACE

An excellent question.

LARRY

I should ask the same of you, Gracie. By the way, you look good. Did you get some work done?

LAURIE

Pops, be nice.

LARRY

Laurie, is there someplace private we can go to talk? Come for a drive with me. No offense Grace, but I want to talk to my daughter in private.

GRACE

Larry, give me the keys to that fancy car and I’ll take it for a spin. You come in and talk to Laurie.

LAURIE

Mom,I don’t want you driving.

GRACE

I won’t go far. What kind of car is that anyway, Larry?

LARRY

It’s a Jaguar. It reminds me of you, Grace. Beautiful on the outside.

GRACE

Our daughter is beautiful on the outside and the inside. I don’t know how she got that way with us as her parents. Laurie, you’re a miracle child.

LAURIE

I’m forty, Mom, hardly a child.

GRACE

Still a miracle that you came out so grounded after all we put you though. With all you’ve had to endure, it’s completely understandable that you’re a few pounds overweight.

LAURIE

Thanks, Mom.

GRACE

Larry, come in and let me take the car.

LARRY

And let you destroy my car too?

GRACE

If you want to be alone with Laurie…

LARRY

(Hesitantly and yet patronizingly) Don’t forget to look in the mirror before you turn, and I don’t mean looking at yourself. And the accelerator is on the right. The brake is on the left side….

(Larry hands Grace the car keys, shaking his head, and walks inside.)

Got any coffee, Laurie? The place looks great!

GRACE

(Gripping the car keys) Larry, our daughter is a modern success story, buying her own house before she was thirty. And she’s beautiful. And kind.

LARRY

It’s a miracle you didn’t screw her up Grace, with your rages, neuroses, and paranoid conspiracy theories.

LAURIE

Mom, I don’t want you driving. Give me the car keys.

LARRY

Well maybe you did mess with her brain a bit. How could you not? I remember how you taught her the alphabet. A was for Angry.

LAURIE

That’s incorrect. A was for Anxiety.

LARRY

I stand corrected.

LAURIE

B was for Betrayal.

GRACE

I knew you were going to screw me over. C should have been for that Cunt of a girlfriend you had.

LAURIE

Mom!

GRACE

I’m going for a drive. I don’t want to be insulted any longer.

LARRY

She’ll be fine.

LAURIE

Pops!

(Grace walks out. Larry plops himself down on the chair.)

LARRY

She says she’s done with me.

LAURIE

What?

LARRY

Nicolette. She kicked me out.

LAURIE

Of your new house?

LARRY

I don’t know what happened. I need a place to stay for a few nights.

LAURIE

Shouldn’t Nicolette be the one who is moving out if she’s the one leaving you?

LARRY

The house is in her name. She wanted equality in our relationship, so I gave her the house to make her feel like an equal partner.

LAURIE

You did what? Pops, how could you think putting the house in her name was a good idea?

LARRY

I thought so too. She called me an uncompromising narcissist.

LAURIE

Well, there is that.

LARRY

I only wanted her to be happy. I need a little time to organize and recover. Laurie, I was wondering if I could stay here for a few nights?

LAURIE

Here? I think you should get a hotel room. That’s what husbands who get kicked out do, they move into a hotel room.

LARRY

She froze my credit cards. She’s out to get me. Why didn’t I see this coming?

LAURIE

You never see it. It’s your blind spot. You can use my credit card.

LARRY

That’s generous, honey. But I don’t feel right about that. I’d like to stay with my daughter. I’m not so young anymore, you know.

LAURIE

Normally I’d say yes, but Mom’s still living here. I can’t kick her out.

LARRY

Maybe she can leave for a few days or a week. Give me a turn.

LAURIE

I am not going to ask her to leave.

LARRY

How are you two getting along?

LAURIE

I’m not kicking Mom out.

LARRY

I understand. I’ll sleep in my car.

LAURIE

Damn. You are uncompromising!

LARRY

If you won’t help me out.

LAURIE

Pops, this isn’t fair to me or Mom. But fine, stay here. Please try to get things sorted out quickly. I hope you kept notes from last time. Your last divorce was a nightmare.

LARRY

The one before that wasn’t bad though.

LAURIE

You were married to Honey-Bunny for less than a month. That wasn’t a real marriage. It was a fling with paperwork. Pops, I don’t know-you’re a hopeless romantic and a narcissist. Those traits are combustible. If you stay here, you have to promise me you won’t let her drive again. In fact, sell your car to get some money. Why am I doing this? You two are going to kill each other.

(The front door opens and GRACE walks in.)

GRACE

You’re right, Larry. That fancy car of yours does practically drive itself. Now, why don’t you take that fancy car and drive it home.

(Grace walks over to Larry, holds her arm up in the air, and drops the car keys in Larry’s lap, but they fall on the floor.)

BLACKOUT