KAMPFGRUPPE PEIPER-LOSHEIM TO LA GLEIZE

STARTING POINT: THE SCHEID RAILROAD BRIDGE-CARRYING BUNDESTRASSE 421 OVER THE RAILROAD JUST EAST OF LOSHEIM, GERMANY (+/- 25 KM SOUTHEAST OF MALMÉDY, BELGIUM) FACING WEST TOWARD LOSHEIM.

The strongest fighting unit in 6th Panzer Army, SS-Oberführer Wilhelm Mohnke’s 1st SS Leibstandarte Panzer Division, was to spearhead the German attack over the Meuse River and onto Antwerp. Mohnke divided his division into four battle groups, (Kampfgruppen) the most important of which carried the name of its commander, twenty-nine year old SS-Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper.

The strength of Kampfgruppe Peiper’s was one hundred and seventeen tanks, one hundred and forty-nine halftracks, eighteen 105mm guns, six 150mm guns, thirty to forty anti-aircraft weapon systems, four thousand eight hundred men.

When Peiper reached the Scheid railroad bridge he found that it had been destroyed. He swung down the dirt track to the right crossing the tracks less than a hundred yards to the north.

Elements of SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny’s 150th Panzer Brigade included a tank company with five disguised Panthers and a single captured Sherman, two infantry companies each with approximately 120 men and a heavy company with mortar, anti tank, pioneer and panzer grenadier platoons, in all about five hundred men.

Mohnke called Peiper to his headquarters in the village of Tondorf, Germany on 14 December to inform him of his unit’s mission in the coming attack. On the following day, Peiper briefed his subordinates and they in turn, informed their company and platoon leaders.

SS-Oberführer Wilhelm Mohnke, commander of 1st SS Leibstandarte Panzer Division.

SS-Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper, commander of Kampfgruppe Peiper.

On 16 December, after the opening artillery barrage, elements belonging to Generalmajor Gerhard Engel’s 12th Volksgrenadier Division began their attack, their mission being to break through the front line positions of the 394th Infantry Regiment. Peiper himself, went to the 12th Volksgrenadier headquarters near Hallschlag to monitor the progress of this infantry attack and was disappointed to learn that things were not going as quickly as planned. That afternoon, therefore, he re-joined his unit and by 17.00 his lead elements reached the Scheid railroad bridge only to find that retreating Germans had blown it the previous September. He quickly solved this problem by taking the dirt trail to the right of the bridge and crossing the line to the northwest. Accompanying Kampfgruppe Peiper was at least one Kriegsberichte (combat photographer) whose film subsequently fell into American hands.

Drive west on 421 in the direction of Losheim passing a large sawmill on the left. At the junction with 265 turn right then first left in the direction of ‘St. Vith-Belgien’.

Between here and the Our River valley, Kampfgruppe Peiper encountered mines that slowed its progress until cleared by engineers. Continue into Belgium downhill then turn right in the direction of Hullscheid, where you keep left turning up hill and in the direction of Merlscheid. In Merlscheid, pause by the small white chapel on the right side of the road.

Continue on the same road and at the junction with N626, turn right in the direction of Lanzerath (2km). In Lanzerath, pause at the building on the left just before the old schoolhouse today known as the ‘Calypso’ night-club.

This building, then known as ‘Café Scholzen’ served as temporary headquarters of the German airborne battalion which had earlier captured the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, 394th Infantry on the high ground overlooking the village. The Germans held their prisoners here in Café Scholzen prior to moving them into Germany. At midnight on 16/17 December, SS-Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper arrived here and immediately set about moving his column out of Losheim. Accompanied by men of the parachute battalion, Peiper’s column began its advance in the direction of Buchholz Station.

Drive just past the ‘Calypso’ stopping by the steel railings on the left. At the end of the railings where a minor road leads left, note the small house on the corner to your front left. This house was the home of Christoph Schur and family.

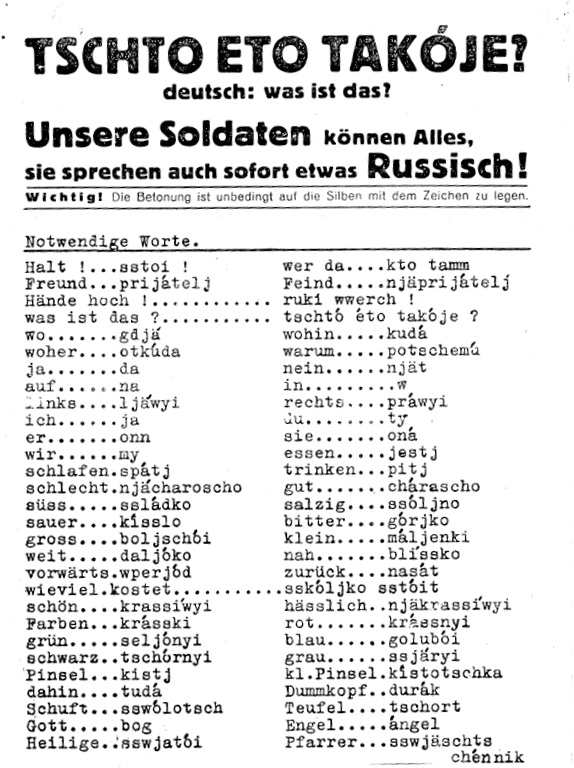

An unidentified SS man left this Russian front dictionary in Lanzerath. (Author’s collection, courtesy Sany and Nicholas Schugens).

The larger building slightly north and across N626 from the Schur home is the Café Palm. It took most of the second day for the bulk of Peiper’s 800 vehicles and men to pass through the rural backwater village of Lanzerath. About midmorning, a group of American prisoners of war captured in Honsfeld a few hours earlier marched down N626 into the village. Among the prisoners were men of Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion 394th Infantry, including Technical Sergeant Luther C. Symons. After interrogating Symons and his buddies in Honsfeld, the Germans marched them back down the advancing column along with two Belgian civilians; a man called Peter Müller from Hasenvenn and his fifteen-year-old nephew Johann Brodel from Krewinkel. The Belgians had tried to escape from the Manderfeld area at the start of the attack and found themselves in Honsfeld as Kampfgruppe Peiper captured the village. As the column of prisoners marched past Café Palm, an SS man standing by a tank outside the building presumed them to be ‘partisans’ and pulled them from the group. He took them into a wooden shed at the south side of the building and shot them both with a pistol. The boy died instantly but his uncle, shot behind one ear, fell to the ground and played dead. Sometime later, when things had calmed down somewhat, Müller rose to his feet and dashed across the darkened street to Christoph Schur’s front door. Inside, Christoph Schur and his wife cleaned Müller’s head wound as more than a score of sleeping German paratroopers slept on, regardless of the activity among them. Suddenly, the door flew open and several SS men entered intent on killing the wounded Belgian. In the First World War, Christoph Schur had served in the Kaiser’s army, he bravely told the newcomers that this was no manner in which to treat a civilian while referring to his service for the Kaiser and showing them a photo of himself in WW1 uniform. Apparently respectful of his status as a veteran, the SS men left the house as quickly as they’d entered. Müller survived but has since passed away as has Christoph Schur. Today, the photograph of the WW1 German Landsers, hangs proudly in the home of Christoph’s son, who still lives in the village.

Continue north on N626 turning left in the direction of Buchholz/Honsfeld. Upon reaching Buchholz, drive on until you reach a bend where the road continues to Honsfeld or turns right in the direction of Losheimergraben. Keep left and pause just upon turning this bend. The forester’s home off to your left existed in 1944.

The Schur family house in the winter of 1943, a year before the battle. (Courtesy Adolf Schur).

The Schur family outside their home. (Courtesy Adolf Schur).

By the time Kampfgruppe Peiper got here, men of the 1st and 2nd Platoons, Company K, 394th lightly held Buchholz, the bulk of their battalion committed elsewhere in its role as the 99th Division reserve. In addition to the few sleeping Company K riflemen, three soldiers of Battery C, 371st Field Artillery Battalion, Lieutenant Harold R. Mayer, Sergeant Richard H. Byers and Sergeant Curtis Fletcher had spent the night in this house. As Peiper’s column entered Buchholz, the infantry put up a token defence. Determined to escape, the artillerymen attempted to reach their jeep, which they’d parked the previous night by the stone outbuilding to your left. Seeing the Germans had already turned the bend towards Honsfeld, they couldn’t retrieve their jeep. Mayer and his men turned back intending to go through the building in the hope of making their escape on foot. German paratroops captured Fletcher but Mayer and Byers made good their escape. Working their way through the trees in the dark, they managed to crouch beneath some low-hanging branches at the roadside just in front of where you are presently parked. As a gap occurred in the German column, they raced over the road and through the trees eventually reaching friendly lines in Hünningen, still held by the 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry blocking Rollbahn C.

Continue west and a little further on at a ‘Y’ junction keep right in the direction of Honsfeld. Drive into the village stopping after the school at the Eifelerhof guesthouse by a bus stop on the right.

Circled; the young Christophe Schur as a German soldier in World War One. (Courtesy Adolf Schur).

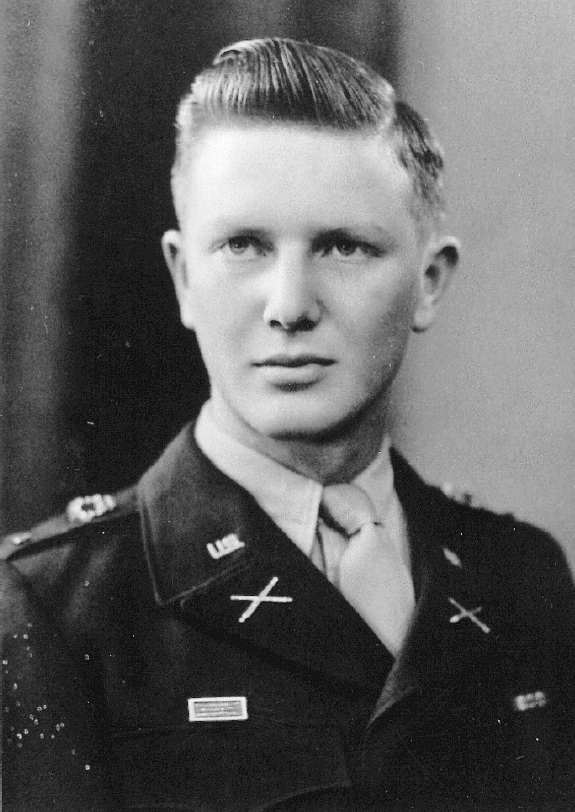

First Lieutenant Harold R. Mayer of ‘C’ Battery 371st Field Artillery Battalion. (Author’s collection, courtesy of Harold and Marie Mayer).

American prisoners captured here, along with some captured later in Büllingen, were assembled in the bar of the guesthouse for interrogation. Private First Class Roger V. Foehringer of Service Battery, 924th Field Artillery Battalion, captured in Büllingen early on the morning of 17 December has vivid memories of what happened:

‘We were taken to a building that reminded me of a big dance hall of some kind. Our troops had been using it as a rest centre where they could get hot food and warmed up. I would say there were about two hundred American prisoners sitting on chairs in this theatre-like room with a stage in front. In a short time, a German officer got up on this stage and told us in perfect English that they were going to interrogate some of us. A young German soldier walked down the aisle by me. I gave him ‘the glare’, he gave me ‘the finger’ and I joined him as he pointed a Luger at me. We went into the wings of a room opposite the stage. He spoke very good English and the first thing he did was to push the pistol in my stomach as he pulled the dogtags off my neck. He was wearing some American clothing and upon examining my dogtags became concerned upon reading that my next of kin was Mrs. William Foehringer. He couldn’t figure out the grammatical connection between a ‘Mrs’ and the name William.’

Shortly after Foehringer’s interrogation, American fighter-bombers strafed and bombed Kampfgruppe Peiper so Foehringer and his fellow prisoners sought refuge in the cellar of the dance hall.

Continue past the old church on your right and pause just around the next bend to the right, opposite a water trough. Note the memorial to the 612th - 801st TD Battalions and attached units of the 99th Infantry Division.

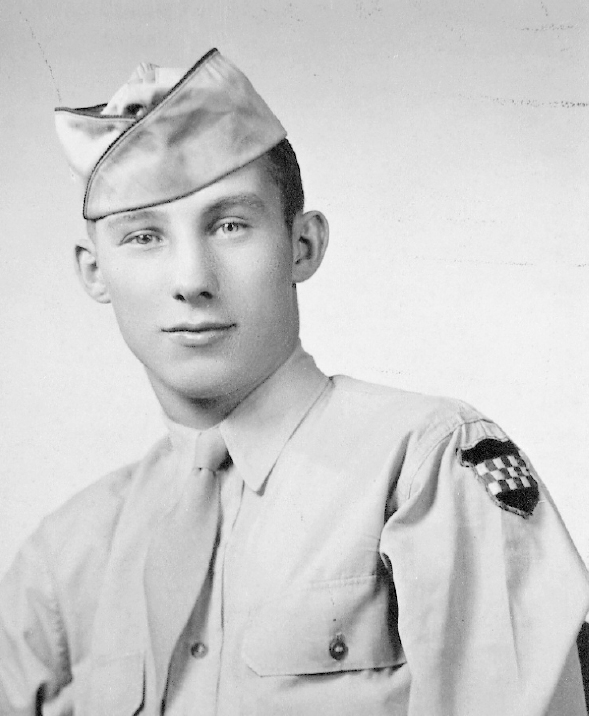

Private Roger V. Foehringer, Service Battery, 924th Field Artillery Battalion. (Author’s collection courtesy Roger and Ruth Foehringer).

Some of the most well-known photographs taken during the battle are those showing three dead GI’s lying face down in the mud in front of this trough as German soldiers try on the dead men’s boots. Roger Foehringer well remembers passing those dead Americans:

‘There were several [three] bodies lying in the road, it was hard to visualise that these were bodies because so many German vehicles had run over them. We tried to avoid walking on them, they were like pancakes, but the Germans made us walk over them.’

Continue up the hill towards Bullingen and after approximately 200 yards stop by the village cemetery on your right.

Here and in the yard of the house just before the cemetery, soldiers of the Kampfgruppe Peiper murdered Americans they’d already taken prisoner. One of the SS men (not identified) involved in killing the men as they exited the farmhouse, bragged about it later in front of a local teenager who later testified of hearing this when called to the post-war trial of surviving members of the Kampfgruppe Peiper. Unknown SS men also murdered a teenage girl named Erna Collas.

Exit Honsfeld following the same road north in the direction of Büllingen. Upon reentering Bullingen pause by the bus stop on your left. Ahead of you the road branches front left and right, you will ultimately keep front left.

Honsfeld. The spot where young men once died.

The bodies of American dead lie by the water trough in Honsfeld. They were later flattened under the wheels and tracks of German vehicles. (US Army Signal Corps).

As Kampfgruppe Peiper approached Büllingen, ten of eleven Piper Cub observation planes, belonging to 99th Division Artillery, managed to take off right under the noses of approaching German tanks as they headed for the improvised airstrip off to the distant left. Over to the right, pilots of 2nd Division Artillery, who couldn’t reach their planes, called friendly fire down upon their aircraft before making good their escape on foot. Captain James W. Cobb of Service Battery, 924th Field Artillery Battalion based in Büllingen, sent a lightly armed platoon under Lieutenant Jack Varner to block this road into town. Varner positioned his men along the hedgerow across the field immediately off to your left. In their role as bazooka team, Sergeant Grant Yager along with Privates Arthur Romaker and Santos Maldanado took up position behind a small rise in the ground which then existed on the spot today occupied by the thatched roofed house off to your front left. Private Bernard Pappel Jr., a 50-calibre machine gunner, placed his machine gun in the hedge to your front where the road splits left and right. Sergeant Yager well recalls that winter’s morning 56 years ago:

‘About 07.00, on Sunday 17 December, Staff Sergeant Zoller, our ammunition sergeant, had us set up what he said was to be a roadblock out of town. Besides our carbines, we carried a number of grenades, one bazooka and a number of bazooka rockets. About 07.30, while the three of us were off to the side of the road, a German tank came over the hill following the road into Büllingen. In just a minute or two, a second tank came over the hill, by which time I’d decided I could fire the weapon without sights just by aiming alongside the barrel. When it was directly in front of us, at about 100 feet, I fired the bazooka. The round hit somewhere on the side and the tank turned part way around in the road. As the crewmen left the disabled tank, I fired my carbine hitting the first two but as I went to shoot a third, my carbine failed.

‘By this time, the rest of the column had come to a halt directly in front of us, only a hundred feet distant. The front vehicle was a halftrack loaded with Panzergrenadiers, this is the group that took us prisoner. At this time, we noticed one of our men, Bernard Pappel, had been wounded and was lying near the side of the road where he had been manning a 30-caliber machine gun. The German soldiers that were there allowed Romaker. Maldanado and myself to give Pappel first aid, using our first aid kits and sulphur powder. A German officer, in a cream-coloured jacket, approached me talking fast in German and poking me with his pistol. I couldn’t understand him and he apparently spoke no English. He walked away, leaving me standing by the halftrack and in a few minutes, the column was ready to move on. They made the three of us sit on the hood of the German halftrack, me in front by the radiator and Romaker and Maldanado behind me nearer the windshield. I heard a single pistol shot and Romaker spluttered “My God! They shot Pappel in the head”.’

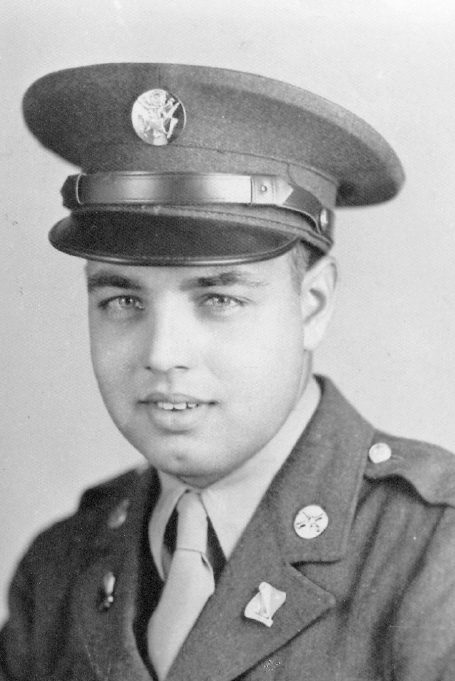

Sergeant Grant Yager of Service Battery 924th Field Artillery Battalion, disabled Peiper’s lead tank as it entered Büllingen early on the morning of 17 December 1944. (Author’s collection, courtesy Grant and Helen Yager).

Men of Service Battery, 924th Artillery Battalion held a roadblock here on the morning of 17 December as Kampfgruppe Peiper entered Büllingen from the direction of Honsfeld. Private Bernard J. Pappel, a machine gunner, was wounded where the small sign is now located. After his capture an SS-Sturmbahnführer shot him in the garden to the right.

Bernard Pappel is buried in Henri Chapelle U.S. Military Cemetery, (Plot C, Row 10, Grave 60) close to Joseph Browzowski (Plot C, Row 8, Grave 38) killed in the ‘Malmedy’ Massacre a few hours after Pappel died here in Büllingen).

Taking the left fork of the road drive on into Büllingen and as you descend into the village, pause at the bend in the road with a stone house ahead of you on the left and a grassy bank to the right.

As the lead tank of Kampfgruppe Peiper began its descent into the village, Privates First Class Roger V. Foehringer and Alfred Goldstein of Service Battery 924th Field Artillery Battalion were walking up this hill carrying a box of grenades. Upon reaching this bend in the road they came face to face with Peiper’s lead tank. Dropping the grenades, they ran off to the front left as machine-gun bullets cracked all around them. Foehringer lay still as a second tank and a halftrack carrying ten or twelve SS-Panzergrenadiers sped down into the village following the first tank. From the garden/yard of the red brick house, just up from the bend, the two GIs could clearly see the vehicles moving down the hill past a stone house on the left (now demolished and replaced by a post-war structure on the same spot). Goldstein spotted two Service Battery cooks who were trying to load a bazooka from the wrong end. Rushing up to them he seized the weapon, loaded it and fired downhill at one of the tanks, the rocket detonating as it hit the side of the house. He and Foehringer then joined other Service Battery soldiers inside the red brick house and for a short while they and other soldiers fired carbines and rifles at the German vehicles moving downhill into the village. Eventually, SS-Panzergrenadiers captured the troublesome ‘Amis’ and after relieving them of watches etc. marched them south in the direction of Honsfeld.

Continue down then uphill straight ahead of you and upon reaching the junction with N632 turn right (East) on the main street. A little further on, take the first left and then keeping right with the church to your left, drive downhill and under the former Railroad Bridge. Pause at the left-hand bend beyond the bridge.

Büllingen church pathway after the battle. (US Army Signal Corps).

While the bulk of Kampfgruppe Peiper turned left at the junction of N632 with the road from Honsfeld, a small group of tanks and halftracks turned right and downhill in the direction of Wirtzfeld. Just prior to this a mixed bag of American vehicles tried to escape from Büllingen via Wirtzfeld to Elsenborn. Sergeant Roger D. Phillips and other men from the 2nd Platoon, Company C, 254th Engineer Combat Battalion, marched this same route and upon turning left at this bend, started uphill out of town behind the fleeing vehicles. As they did so, the approaching German armour began firing shells past the engineers at the American vehicles hitting a weapons carrier and setting it alight before it reached the top of the hill.

Phillips and his buddies hastily left the road in a field off to the right as machine-gunners on enemy halftracks took them under fire. With no possibility of concealment, Phillips’ platoon leader, a lieutenant named Anderson, ordered his men to throw down their weapons and surrender. Panzergrenadiers marched the engineers back down to Büllingen and assembled them atop the Railroad Bridge. As a young SS-man relieved Phillips of his watch, American fighter-planes swooped down and began circling Büllingen a couple of times. The Germans quickly herded their prisoners down off the railroad and obliged them to stand around tanks and other vehicles as the planes circled above. The fighters swooped down and upon spotting khaki-clad troops assembled around the vehicles, the pilots refrained from strafing or bombing this part of the German column. The tanks and halftracks, which had earlier captured the engineers, attacked Wirtzfeld, then defended by men of 2nd Division Artillery Headquarters, the 2nd platoon of Company C, 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion and a 155mm howitzer of Battery C, 372nd Field Artillery Battalion under the command of First Lieutenant Charles Biggio. Together, these American defenders stopped this attack on Wirtzfeld, knocking out at least two enemy tanks in the process.

Turn around and head back the way you came turning right upon reaching the main street just past the church. At the West End of Büllingen, turn front left off N632 in the direction of St. Vith. Pause by the trees on the left just before the ‘Gendarmerie’ (Polizei). To your left is the former cattle market, which in 1944 was an American fuel depot.

Some of Peiper’s halftracks and tanks were able to re-fuel here and at 09.00, the column continued its advance in the direction of Möderscheid. A number of books erroneously suggest that Peiper’s men murdered American prisoners here having forced them to load jerrycans onto the German vehicles. No such massacre ever occurred in Büllingen.

Continue west until you reach the first traffic circle. Here you continue straight ahead before taking a minor concrete road through the woods to your front passing sawmills off to your left and right on the way to Möderscheid. Upon entering the village, you take the first right turn and drive downhill past the village church. Turn right at the next junction in the direction of Schoppen where you take a left turn sign posted ‘Amel’. At the next junction turn right in the direction of Faymonville then at the western end of the village just before the sign for ‘Schoppen’ (with a red bar through the name) turn left on a minor road. Follow this road through the fields past a couple of small factories (on the right), a kilometre further on, the road turns sharply to the right. At this point take the minor road straight ahead. At the next ‘T’ junction, turn left. The first building on the left of this road is a large farmhouse called ‘Stephanshof’. Pass a second farmhouse (on the right) and take the next right, pausing immediately after turning the corner. The woods to your left are where Captain Charles B. MacDonald of Company I, 23rd Infantry was wounded in a night attack aimed at outflanking a German roadblock on 18 January 1945. The roadblock was across the Ondenval to Amel road and MacDonald and four of his men were wounded in a north-south firebreak close to the far side of the woods and overlooking the road.

Drive downhill and past an old farm on the right then turn second left downhill into Ondenval. In Ondenval turn right on N676 then turn first left in the direction of Thirimont, continue uphill, passing the village cemetery on your right (outside the village) and in Thirimont keep on the main road passing the modern village church on the right. At the western edge of the village where the road takes a major bend to the right, pause. Note the small lane to your left.

Shortly before noon on 17 December 1944, Kampfgruppe Peiper reached this point in its dash to the Meuse River. Here Peiper intended taking the shortest route to Ligneuville, which meant sending elements of his spearhead down this lane. Unfortunately for them, these vehicles got bogged down between here and the Baugnez-Ligneuville road. The bulk of the column therefore kept to the main road leading north/northwest of Thirimont.

Continue out of the village on the main road, passing through a small patch of woods and pausing about 150 metres further on.

A German combat photographer took this shot of men from the 1st SS Panzer Division off to Peiper’s south flank at Kaiserbaracke and the film was later captured by the Americans. (US Army Signal Corps captured film).

American troops Evacuate Civilians in Malmedy in front of the Cathedral. (US Army Signal Corps).

An American MP directs traffic through Malmedy after its mistaken destruction by US bombers. (US Army Signal Corps).

Upon reaching this point, across the open field to their front left, the spearhead Panzergrenadiers and tankers of Kampfgruppe Peiper could clearly see the Baugnez road junction and American vehicles turning south in the direction of Ligneuville. Today, the view has changed considerably given the amount of construction in the immediate vicinity of the crossroads. From where you are parked, the crossroads is hidden by a large blue metallic building, whereas in 1944 only a few buildings existed, today the area is largely built up. To give the reader the view on the American side, this itinerary takes you down into Malmedy prior to visiting Baugnez, the junction where the ‘Malmedy Massacre’ occurred.

Carry on until you reach the ‘T’ junction, with the main road (N632) where you turn left in the direction of Malmedy. Continue downhill a couple of kilometres, crossing over the railroad and passing the Carrefour supermarket on the right. Pause at a convenient place on your left approximately 90 metres before reaching the next traffic circle.

Around 12:30 on 17 December 1944, a column of trucks and jeeps belonging to Battery B, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, pulled up here outside the (now demolished) command post of Lieutenant Colonel David E. Pergrin’s 291st Engineer Combat Battalion. Pergrin advised Captain Mills, the Battery B commander against continuing on to St. Vith via Baugnez since he had reports of German armour approaching Malmedy from the east and felt it would be safer for them to take an alternative route to St. Vith. They chose to ignore his advice and the column set off towards its fateful encounter with ‘Hitler’s Own’ – SS Leibstandarte.

Move on into Malmedy and park in the town centre.

In three ‘friendly fire’ incidents American aircraft completely destroyed the town centre (except for the cathedral and an obelisk in the main square) killing American soldiers and Belgian civilians alike. In the grassed area to the right rear of the cathedral are four large black stones commemorating the civilian victims of the bombing and listing their ages and respective names. Around the other side of the cathedral is a large stone bearing the names of all the American units that spent time in Malmedy either at the liberation in September 1944 or later during the ‘Bulge’. The stone mason obviously didn’t realise that the 99th Infantry Battalion (Separate) and ‘Hansen’s Norwegians’ are one and the same, neither could he or she spell ‘Engineer’ or ‘740th’!

Return to Baugnez following road signs for Waimes. Turn right on N62 in the direction of St. Vith and park in front of the large blue garages to your left, just past the monument.

Note the ‘Baugnez 44 Historical Center’. (www.baugnez44.be)

The incident most often referred to as the ‘Malmedy Massacre’ occurred on the right side of N62 in the field directly outside the stone farmhouse across the road from the prefabricated blue building. In 1944 this was an open field, the red brick house and its driveway having been built post-war. The Battery B column of trucks and jeeps came under fire after the point turned due south in the direction of Ligneuville. The men exited their vehicles to be marched back up to the field opposite you by their German captors.

At the request of the author, Danny S. Parker, himself the author of Hitler’s Warrior, a book on Jochen Peiper and ‘Fatal Crossroads’ has kindly summarized the massacre:

‘The massacre was neither a premeditated slaughter, nor a complete battlefield accident. There were elements of both, primarily brought on by the actions of Max Beutner or Eric Rumpf (which, is not completely clear). Suffice it to say that the battlegroup commander, Obersturmbannführer Jochen Peiper was not there. However, Werner Poetschke was present and fuming after a particularly testy encounter with Peiper regarding the lack of progress of the tank group and the missing nature of Werner Sternebeck’s spearhead (unknown to them it had already motored on ahead). Peiper was also annoyed that the firing would alert the American forces in Ligneuville nearby. He had learned that an American general, (General Edward Timberlake) was there and having never captured one before, was intent on that prospect!

A post-war house now stands just right of the location of the Malmedy Massacre. Prisoners from Battery B, 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion were murdered just left of where the house now stands.

The grim discovery under the snow – the body of a victim with an identification marker. (US Army Signal Corps).

In any case, Peiper gave Poetschke an earful about having shot up the trucks, suggested that he impress them into the column and drove on. His exact words to Poetschke were ‘What is the meaning of this sitting around! The little there is to be done here can be taken care of by the infantry!’ With that, Peiper in a jeep driven by Paul Zwigart, zoomed off. On the radio. Peiper immediately ordered Arndt Fischer to proceed to Ligneuville at maximum speed. Peiper drove right behind him. Peiper gone, Poetschke then dismounted from his tank to approch the prisoners walking up to the crossroads. His blood must have boiled when he found that the surrendered Americans ignored his request in broken English (Chauffeur? Chauffeur !) that some of the Americans volunteer to drive the trucks for his column. They kept walking and completely ignored him. They did not even turn their heads! Ignoring an angry SS officer may have sealed their fate. After that, Poetschke gave Rumpf an earful and prepared to leave himself. What he said is unclear as Beutner died at Stoumont a few days later and Rumpf appears never to have been completely honest regarding his involvement. That is the way command works--negative admonishment flows downhill. By the time, the shooting began, it appears that Poetschke, too, was headed south. A few tanks of the 7th Panzerkompanie were parked by the prisoners. (Hans Siptrott, Roman Clotten and Pilarsek further back). Several halftracks from 9th Panzer Pioniere Kompanie were also present. In his original deposition (later retracted at Landsberg), Siptrott indicated that he was ordered to fire on the prisoners, but refused claiming inadequate ammuntion. However, a Romanian SS volunteer in his tank, Georg Fleps, popped out of one tank hatch, produced a pistol and fired. As if on signal, several machine-guns on the nearby halftracks opened fire. Most of the GIs were stood in the field when the shooting started (first pistol shots), but not all. At least two Americans bolted for the rear at the first shot. The rest stood when the firing began, but there was a good amount of shouting. Such is understandable; men were dying. It is noteable that Siptrott had never denied the shooting that ensued, and has always maintained that his first reaction to the above was to kick Georg Fleps and throw his Mark IV in gear to get away from this mess. A detailed map shows the position of each body in the field by the crossroads. It makes it clear that a mass shooting did happen to men standing there although with a number shot as they ran. A number ran at the first shots. Later, in Ligneuville, an angry Siptrott reported on Flep’s actions, knowing that this whole incident would create a lot of trouble. He was right.

After the initial shooting, members of the pioniere battalion moved through the mass of Americans lying in the field and shot anyone who appeared to remain alive. Amazingly, after the Germans departed the scene later that afternoon, some thirty Americans, who were still alive and feigning death, rose suddenly from the field and ran towards friendly lines. Many would escape and report an incident that would haunt Peiper and his men for the rest of their days.

Continue down N62 in the direction of Ligneuville. As the road begins to descend and you approach the first major bend to the right, note the narrow dirt road that joins you from the left. This is the place at which Kampfgruppe Peiper would have joined the main road, had its lead vehicles not gotten bogged down upon leaving Thirimont.

Drive down into Ligneuville stopping at the monument on the right, just before the Hotel du Moulin.

Situated several kilometres west of the front lines on 16 December, Ligneuville had been considered relatively ‘safe and secure’ by GIs of Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division and the staff of Brigadier General Edward W. Timberlake’s 49th Anti-aircraft Artillery Brigade. The Service Companies of the 14th Tank, 16th Field Artillery and 27th Armored Infantry Battalions were scattered about the village. Two companies were across the Amblève River to the south and that of the 14th Tank Battalion in the vicinity of where you are now parked. The Hotel Du Moulin, reputed for its fine cuisine, served as General Timberlake’s headquarters.

Early that morning, General Timberlake learned of the breakthrough in the 99th Division sector via a radio message from one of his front line firing batteries near Bütgenbach and prepared his headquarters to evacuate Ligneuville at short notice. Shortly after 13:00, Timberlake and his staff hurriedly departed.

Tanks and halftracks of SS-Obersturmführer Werner Sternebeck’s spearhead led the rest of the Kampfgruppe down into the village. Here, the German column encountered its first American armour in the shape of tanks of the 14th Tank Battalion. As Sternebeck’s vehicles moved down into the village they came under fire from an American tank-dozer (A Sherman tank with a bulldozer blade attached) positioned in a barn on the high ground to your right rear. The American tank knocked out the third tank in the column, a Panther commanded by SS-Untersturmführer Arndt Fischer, as it passed the Hotel Du Moulin on the right and then the village church off to its left. The tank-dozer then hit a follow-up halftrack which burst into flames outside a small house about 75 yards up the hill to your left rear.

Another German halftrack subsequently knocked out this troublesome tank-dozer which Peiper himself is reputed to have gone stalking with a Panzerfaust, having left his command vehicle, a halftrack, by the church.

The monument to your right commemorates several GIs murdered by an SS sergeant. At least one American survived this incident and later fled the scene only to be re-captured elsewhere in the village.

In a sworn statement made after the war, SS-Oberscharführer Paul Ochmann stated that he and SS-Sturmmann Suess of Kampfgruppe Peiper murdered these prisoners:

‘Suess stepped from his vehicle (a halftrack) after having previously taken a weapon from the vehicle. I no longer know what kind of weapon it was. Together with Seuss, I led the prisoners past the SPW (halftrack) of SS-Unterstrumführer Hering over to the other side of the road. I cannot tell any longer exactly how far I led the prisoner (sic) but it was hardly more than a hundred metres, probably even less.

‘Thereby I again went back a short distance on the road on which we came, therefore north in the direction toward Malmedy.

‘In the vicinity of the cemetery at a place where the terrain descends on the right of the street, I stopped the prisoners, who were marching one behind the other. (If I now say ‘right’, I mean right as one goes in the direction toward Malmedy). I formed them right at the edge of the road for I selected this location intentionally because there the bodies could drop right down the steep terrain without lying in our way.

I then indicated to the prisoners with my hand that they should place themselves with their backs towards me and therefore with the face towards the slope, as I intended to kill them by a shot in the neck. I know that by a shot in the neck the victim falls forward.

Thereupon, I first shot the first American prisoner of war from a distance of about 20cm. I shot him with a shot into the neck from the rear because I know from my service with the ‘Totenkopf Einheit’ that this is the customary way to shoot people. All told, I myself shot and killed with my pistol in this manner four or five of these American prisoners of war. SS-Sturmmann Suess of the 9th Panzer Company shot the other prisoners in my presence. About 500 metres north of the place where SS-Sturmmann Suess and I shot the prisoners stood another eight prisoners of war. I believe an officer was among them. I brought these prisoners into a hotel located in the village because I was of the opinion that enough prisoners of war were already bumped off. These eight prisoners whom I brought to the hotel were still together with some other wounded American prisoners of war when I left the hotel around noon on 18 December 1944.’

SS panzergrenadier belonging to the 1 SS Leibstandarte Panzer Division enjoys a cigerette ‘captured’ from the Americans during the drive to the Meuse.

Reverand Francois Emes officiates at the temporary burial of civilians killed by the Waffen-SS in Stavelot. (US Army Signal Corps).

Ochmann later retracted this statement.

Marie Lochen, a then resident of Ligneuville witnessed this incident and testified to the effect of having seen two Germans shoot these prisoners.

At about 17:00, the Kampfgruppe Peiper began leaving Ligneuville.

Continue through the village crossing the Amblève River Bridge and at the top of the hill turn right in the direction of Vielsalm/Pont on N660. Pass through Pont and under the viaduct carrying E42. Take the next right in the direction of Stavelot and keeping off E42. Drive six kilometres to Vau Richard and here watch out on the right for a house with a (false) red brick finish. Past this house, keep your eyes peeled for a small road leading uphill to your left rear. Turn up this road sign posted as a ‘dead end’ and park where the road takes a sharp bend uphill to the right. Walk up the dirt trail leading past a single storey house on the left and into the woods. Just as you enter the trees note the monument to your right.

Here where the monument stands, unknown SS men took twelve American prisoners and three local civilians and murdered them in cold blood. Later, as the battle wound to a close, local villagers searching for the missing civilians discovered the bodies. The GIs lay where the monument now stands and the civilians across the trail where a wooden bench marks the spot.

The murdered soldiers were men of Company A, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion of the 9th Armored Division. This unit would earn itself a place in history a few months later when, under Captain Karl Timmermann, it captured the Ludendorf Bridge over the Rhine River at Remagen.

Return to the main road turning left in the direction of Stavelot. At the West End of the village (Vau Richard) note a narrow lane leading to the front left between two houses. The house between the lane and the main road was that of Albert Petit and his family.

SS-Sturmbannführer Knittel (right) commander of 1 SS Leibstandarte Panzer Division’s Reconnaissance Battalion, confers with his adjutant, SS-Obersturmführer Leidreiter, during the fighting around Stavelot.

A photograph taken by a German Kriegsberichter on 18th December 1944 shows SS-Sturmbannführer Gustav Knittel commander of the Reconnaissance Battalion of 1st SS and the commander of his 3rd Company Obersturmführer Walter Leidreiter studying a map.

Continue a few hundred metres in the direction of Stavelot and as the road begins to descend prior to reaching the rock outcrop note a small moss-covered stone foundation just left of the road. Pause here.

Locally, this spot is known as ‘La Corniche’ and this stone foundation is all that remains of a pre-war Belgian army guard hut built for sentries guarding the road from Ligneuville.

At about 1830 on 17 December 1944, Sergeant Charles Hensel and his twelve-man squad from Company C, 291st Engineer Combat Battalion placed mines across the road and a bazooka team and .30- calibre machine gun a little further downhill. Hensel sent one man, Private Bernie Goldstein beyond the roadblock to the guardhouse to keep watch for the approaching Germans.

About 21.00, Peiper’s spearhead reached the engineer roadblock and after a brief exchange of fire during which Goldstein escaped up a path through the trees above the road, Peiper ordered the column to bivouac overnight. Hensel’s men climbed into their truck and freewheeled silently down into Stavelot.

Continue downhill and stop just past the last bend on the high ground overlooking the ancient town of Stavelot to your front right.

The high wooded hill on the far side of town was the location of U.S. First Army Fuel Dump number 3, a massive fuel depot, which fortunately, for the Americans, Peiper’s column never spotted.

In Stavelot, a large red brick building, clearly visible from where you are parked, served as a shelter for civilians during the battle given the thickness of its walls and an extensive network of cellars. This building features prominently in the story of Marcel Ozer, a local man and Tony Calvanese, an American soldier.

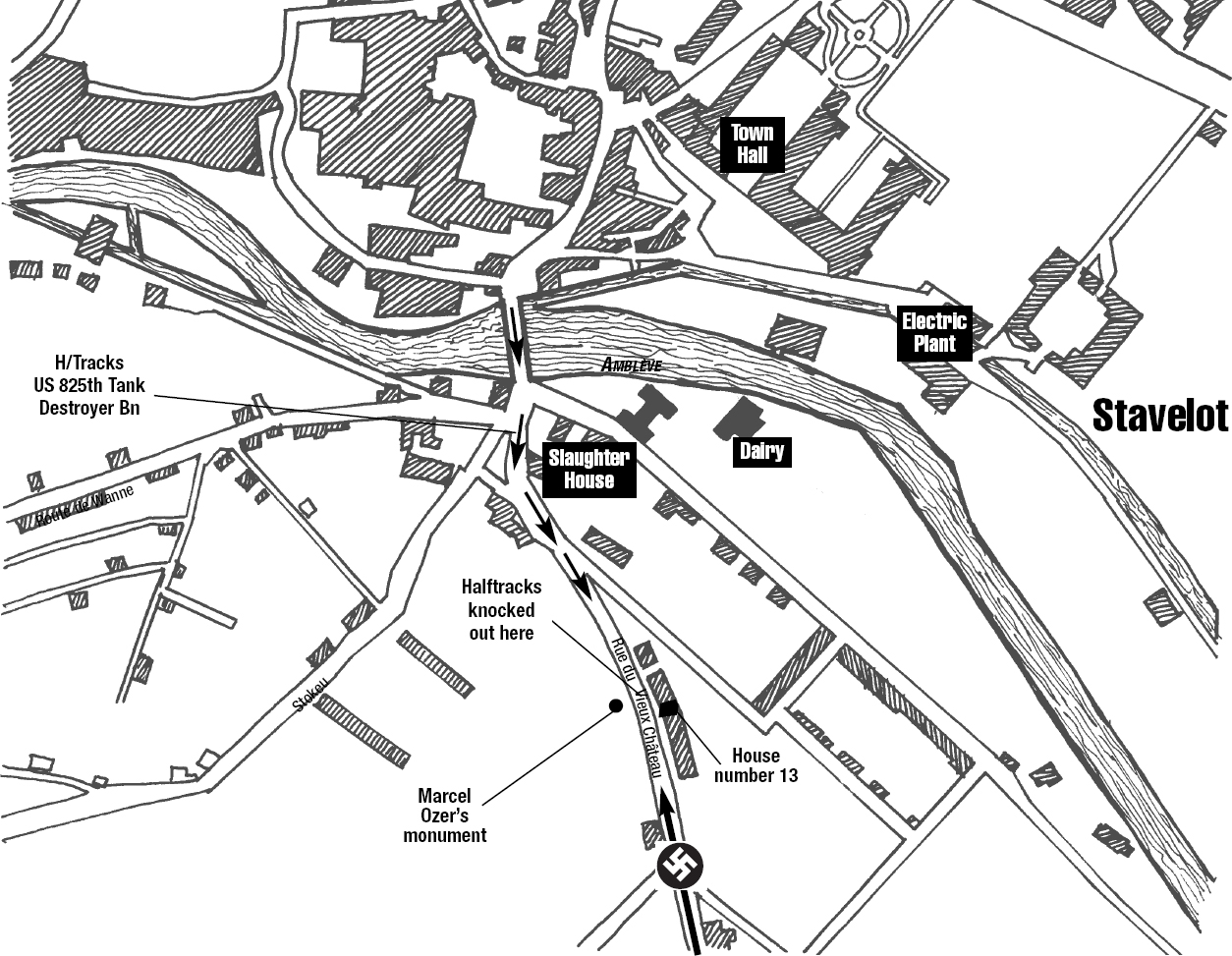

Continue downhill and upon reaching the brick houses on the right, the more sharp-eyed traveller can still spot traces of gunfire in the brickwork. Bullet holes bear now silent witness to the passage of Kampfgruppe Peiper. Closer to the bottom of the hill (opposite house number 13) keep an eye out for a small monument on the left side of the street. Pause here.

Marcel Ozer, a ‘Stavelotain’ erected this and other memorials on his own initiative. It commemorates the men of the 825th Tank Destroyer Battalion, 291st Engineer Combat Battalion and 526th Armored Infantry Battalion killed here in Stavelot and on the road to Trois Ponts.

At about 06.00 on 18 December, four halftracks of Company A, 526th Armored Infantry Battalion and two towed 3″ anti-tank guns of Lieutenant Jack Doherty’s 1st Platoon, Company A, 825th Tank Destroyer Battalion, crossed the Amblève River bridge. Second Lieutenant James Evans positioned his 3rd Platoon, Company A, 526th Armored Infantry Battalion just Southeast of the bridge. Sergeants Jonas Whaley and John G. Armstrong the two tank-destroyer commanders turned their halftracks sharp left upon crossing the bridge and found themselves up a dead-end street. They quickly turned around and began moving uphill on La rue du Vieux Château in the direction of the advancing German column. In the lead tank, SS-Rottenführer Eugen Zimmermann’s gunner spotted Armstrong’s halftrack and set it alight with his first shot killing some of its crew (Sergeant Armstrong and five other soldiers of Company A would die in this action). The survivors sought refuge in nearby houses or fled back across the river. The Germans then hit the 1st and 3rd Platoons of Company A, 526th Armored Infantry and Sergeant Jack Ellery commanding a machine gun squad was killed on the bridge. The surviving infantrymen withdrew across the bridge taking up position in houses on the far bank.

Marcel Ozer with his wife Julia just after the war. (Courtesty Marcel and Julia Ozer).

Soldiers of 1st Platoon, Company A of the 825th Tank Destroyer Battalion inspect the wreckage of two of their guns and halftracks knocked out by Kampfgruppe Peiper early on the morning of 18 December 1944. (Courtesy Mrs. Frances W. Doherty).

Corporal ‘Bob’ Hammons a survivor from Sergeant Whaley’s halftrack sought refuge in a shed and later a basement potato bin before successfully wading the icy waters of the Amblève and reaching friendly lines in nearby Malmedy.

Private Tony Calvanese, shot in the left thigh, managed to find shelter in, what today is, house number 13. Later that morning when a passing SS officer shot at him through a window, Tony climbed out of a large hole at the rear of the property and crawled to a nearby dairy to find it full of terrified civilians. Among them were Marcel Ozer and Louis van Lancker, two young men in their mid-twenties. Earlier that morning, in the dark, the two Belgians had tried to escape from Stavelot but ran into SS Panzergrenadiers on the bend downhill from your present position. These Germans apparently chose not to shoot the intrepid pair thus risking alerting nearby American troops and told them to ‘get lost’. Hurrying away, the Belgians went straight to a dairy in the street behind these houses and were present later that morning when Tony Calvanese showed up.

Continue downhill pausing by the monument under a copper beech tree on the left as you turn right toward the bridge. This plaque commemorates the civilian men, women and children murdered by the Waffen-SS in and around Stavelot.

Prior to crossing the bridge, park on the right side of the road.

The halftrack to your left, honours the men both American and Belgian who kept Peiper’s main supply route closed after the Americans blew the bridge behind him on 19 December. The dairy to which Tony Calvanese escaped was along the street to your right when facing the bridge.

Private Tony Calvanese of Agawam Massachussetts after his rescue by the citizens of Stavelot. (Author’s collection, courtesy Tony Calvanese).

Stavelot after heavy shelling by the Americans. This vital bridge over the River Amblève was heavily contested for the best part of two days. A Königstiger can be seen on the far side of the bridge.

At 08.00 on 18 December, German mortar and artillery fire hit Stavelot as tanks of SS-Panzer Regiment 1 crossed the then narrower stone bridge over the Amblève.

At about 10.00, it became obvious to the civilians in the dairy that if SS men discovered Calvanese in their midst, they may well vent their anger on all present. Marcel Ozer volunteered to wade over the river in order to try and get help from the Americans on the far bank. Setting foot in the icy water, the current proved too strong and swept him off his feet and a short distance downstream. He nonetheless struggled free of its grasp and climbed up the riverbank soaked to the skin. He rushed home to change his clothes then returned to the dairy, where he and other townspeople decided to evacuate the injured GI. A local Red Cross worker, Madamoiselle Berthe Beaupain said she could get a stretcher from a nearby Red Cross building and promptly set off to collect it and her nurse’s uniform. Arriving at the house in question, she found it occupied by twenty local people and Father Antoine Bernard, a priest from the German speaking village of Amel. Together, she and Father Bernard made their perilous way through advancing SS Panzergrenadiers and gunfire, back over the bridge to the dairy with the much-needed stretcher.

Quickly, the courageous Belgians decided to evacuate Calvanese across the bridge then being crossed by the bulk of Peiper’s column. Marcel Ozer and Louis van Lancker volunteered to carry the injured American across the river accompanied by Berthe Beaupain, her brother Gustav and Father Bernard. Upon reaching your present location they paused as a Panther tank rounded the bend and began crossing the bridge. Marcel Ozer then seized the initiative and urged the group into the depths of hell. Walking behind the tank, they passed the crushed remains of Sergeant Ellery while further on a dead SS officer sat with his back propped up against the bridge parapet with his legs turned sideways in order to prevent the tanks from running over him. Both small and larger calibre gunfire raked the bridge as the Belgians raced across the river.

On the evening of 19 December 1944, American Engineers blew the bridge span nearest the far bank, effectively cutting Peiper’s link with the rest of 1st SS.

Cross the bridge and upon doing so, pause on the far side.

Across the Amblève, Marcel Ozer and his companions turned right along a narrow street and made their way unhindered to the large red brick building you saw from the top of the hill.

Continue up the street keeping front right at the ‘Y’ junction and pausing by the archway on the right.

Here in the present day city hall, the group separated after placing Tony Calvanese in part of the extensive cellar system beneath the building. While the others returned across the bridge, Marcel Ozer stayed behind with Calvanese until soldiers of the 117th Infantry regained possession of the buildings facing the river and evacuated the wounded American.

Continue up the same road turning right at the first major junction. Drive straight ahead past a mini traffic island to the next traffic circle where you join the N68 (second exit) in the direction of Trois Ponts. Pause at the western edge of town just past the right turn marked ‘Parfondruy’. Peiper’s column drove up the old main street of Stavelot but present day traffic signs won’t permit today’s traffic to do likewise.

After 19 December, the Germans made numerous attempts to recapture the Amblève River Bridge head on from the south bank of the river; they also attacked in strength from the direction of Trois Ponts. Here at the western edge of town, SS-Obersturmführer Manfred Coblenz led his attacking 2nd SS Reconnaissance Company under heavy fire up the Trois Ponts road to capture the very first few houses in town but got no further. In his command post just west of Stavelot, SS-Sturmbannführer Gustav Knittel ordered elements of his Reconnaissance Battalion to move east and north of the main road to capture Parfondruy and hit Stavelot from the north. Upon clearing Parfondruy, SS-Obersturmführer Heinrich Goltz and his men ran into American opposition at Renardmont and therefore joined Coblenz in further attempts to take Stavelot from the west.

Medics of the 82nd Airborne Division load a wounded SS man onto a stretcher. He was aged 20 and had been in the service for four years at the time the Americans captured him in Erria. (US Army Signal Corps).

Civilians in Parfondruy and other hamlets west and northwest of Stavelot suffered the wrath of the attacking Waffen-SS when Goltz’s men massacred men, women and children alike.

Bitter fighting at the western edge of town and in the villages to the right (north) side of the road to Trois Ponts continued unabated until dusk on Sunday 24 December.

Continue west in the direction of Trois Ponts pausing after one kilometre opposite a large red brick farmhouse on the left. This is the Antoine Farm, SS-Sturmbannführer Gustav Knittel’s command post during the attacks toward the western edge of Stavelot. Knittel and his staff shared their basement refuge with numerous terrified civilians. The east gable of the house still supports its hard-earned battle scars in the shape of gunfire damage.

Continue in the direction of Trois Ponts and 2.2 kilometres further on note the Petit Spai Bridge to the left of the road. Pause here.

On Thursday 21 December 1944, infantry elements of the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Battalion, crossed the swollen Amblève River here at Petit Spai, then moved up the high ground to your right on their way to the fighting in and around Parfondruy. Soon after these infantrymen crossed the bridge their commander sent his Jagdpanzers (tank destroyers) in their wake. Under the weight of the lead Jagdpanzer, the Petit Spai Bridge collapsed into the turbulent waters of the Amblève. All further attempts by the 1st SS Pioneer Battalion to bridge the river during daylight failed but that night they managed to put in an infantry footbridge. Ultimately on Christmas Eve Gustav Knittel ordered his remaining men to withdraw across the river using the twisted remains of this infantry bridge.

Continue in the direction of Trois Ponts stopping just before the two railroad tunnels.

In 1944, the building off to your left just before the tunnels was known as the Hotel Lifrange. Recognising the importance of stopping Peiper from moving through Trois Ponts, a mixed bag of American defenders set about blocking the road at this point while men of the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion wired the nearby Amblève River Bridge for possible demolition.

Lieutenant Richard Green commanding the 3rd Platoon of Company C, 51st Engineer Combat Battalion, had orders to defend east of the railroad tunnels near Trois Ponts, supported by a 57mm anti-tank gun crew of the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion. Two other men of the 526th, Corporal Bruce Frazier and Private First Class Ralph J. Bieker positioned themselves 250 yards east of the anti-tank gun with the intention of pulling a ‘daisy chain’ of mines in front of the lead German tank as it approached from the direction of Stavelot. The job done, the two GIs were to run back to the anti-tank gun just east of the hotel.

Shortly before noon on the 18th December the lead tank nosed around a bend towards the 57mm anti-tank gun. Frazier and Bieker fired several rifle shots at the approaching Germans as the tank and others behind it stopped at the daisy chain. Other engineers came back down the road to Lieutenant Green’s position to warn him of the Germans’ approach. By this time the antitank gunners and engineers in the vicinity of the gun could see the lead tanks and heard others moving down the road through the trees. The gun crew had to make every round count since they only had a total of seven rounds available. As they pondered when to open fire, the third tank in the column fired four rounds in quick succession. One shell skipped over the river to their backs and a second no more than six inches above their heads. Another hit a tree behind the anti-tank gun; felling the tree and showering fragments in the area. The anti-tank gunners opened fire and one of their first rounds caused the lead tank to start smoking. There was some difficulty initially with ammunition for the anti-tank gun since seven rounds would not suffice to stop the attacking enemy armour. Captain Robert N. Jewitt, Supply Officer of the 1111th Engineer Group headquarters in Trois Ponts started throwing shells across the road to Lieutenant Green, who passed them to another man who in turn handed them to the gun crew. The defenders clearly heard the detonation as their buddies in town blew two of the three bridges behind them effectively cutting them off from Trois Ponts. The 1111th Engineer Group commander, Colonel H. Wallis Anderson observing with binoculars from across the river, counted a total of nineteen tanks that came through the position and then turned right in the direction of Coo. Back at the anti-tank gun the German shells got closer and closer until one hit the base of the gun killing the gun crew. Their position now hopeless, the remaining engineers piled into a halftrack and a 2½ ton truck and proceeded by their only escape route – the road to Stoumont. The sacrifice made by this anti-tank gun crew is commemorated on Marcel Ozer’s monument on La rue du Vieux Château in Stavelot. Shortly after this action, between the tunnels, men of the Headquarters Company, 1st SS Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion murdered brothers Gustave and Oscar Job of Stavelot.

Continue through the tunnels and turn left in the direction of Hamoir/Vielsalm. Cross the bridge then turn around and drive back over it stopping on the north side. Note the plaque on the wall of the bridge commemorating the role of Captain Sam Scheuber’s Company C, 51st Engineer Combat Battalion in the defense of Trois Ponts.

By the church in Trois Ponts a stone marks the passage of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. (Author’s collection).

As Peiper’s tanks made their way through the tunnels men of Company C blew the Amblève River Bridge effectively stopping Peiper from taking the direct road to Werbomont and forcing him to take the alternative road in the direction of Coo. Men of the 51st and 291st Engineer Combat Battalions defended Trois Ponts until relieved by incoming soldiers of the 505th Parachute Infantry of the 82nd Airborne Division. Major Robert B. Yates, Executive Officer of the 51st, witnessed SS men chasing a young boy, thirteen year-old Michel Nicolay between the houses on this side of the blown bridge. From across the river, Major Yates fired his Colt 45 in a vain attempt to help the unfortunate boy whom the pursuing SS men caught and later murdered.

Colonel Anderson, the Engineer Group Commander, sent his Motor Pool Officer, Captain A.P. Lundberg to warn First Army Headquarters in Spa of the approach of Kampfgruppe Peiper. Captain Lundberg and his driver were to run smack into Peiper’s spearhead as it neared the Neufmoulin Bridge

In the small park in front of the Trois Ponts parish church is a monument to the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

Continue on N63 in the direction of Liege/Remouchamps passing through Coo and ultimately entering La Gleize. Upon reaching the village take the second road to the left driving down a narrow lane marked ‘Rahier 7.’ At the time of writing there is also a sign saying ‘Descente de L’Amblève en Kayak arrive Cheneux.’ Pause at the bottom of this short lane before turning right. Note the impressive Château Froidcour in the trees to your front. This castle, ancestral home to the De Harenne family, figured prominently in the battle since a stone farmhouse in its grounds served as Peiper’s command post while in the vicinity of Stoumont. The Germans also used the castle bedrooms to hold American prisoners captured in the La Gleize/Stoumont area.

Turn right in the direction of Cheneux/Rahier following the winding road down to the Amblève River Bridge at Cheneux where you pause.

SS-Obersturmbannführer Peiper wearing his Knight’s Crossed with Oakleaves and Cross Swords.

At about 13.30 on 18 December, the spearhead of Kampfgruppe Peiper began its descent toward the river at Cheneux. Spotting movement in the vicinity of the bridge, the machine gunner on the lead Panther opened fire fully expecting the bridge to be blown before the column reached it. Unfortunately, the five people spotted near the bridge were civilians, a man and four women. One woman died instantly and a second shortly afterwards. The man and a third woman were less seriously wounded.

Continue uphill toward the village pausing at the first bend to the right.

Minutes later, as Peiper’s lead vehicles crossed the bridge, American fighter-bombers strafed and bombed the column wrecking three tanks and five halftracks in the process. Peiper and Gustav Knittel sought temporary shelter in the pre-war Belgian pillbox to your left and overlooking the bridge. During this attack, a bomb exploded knocking out a panther tank and blowing out the gable end wall of the Dumont house to your front right.

Continue uphill into Cheneux noting the splendid view of the Château Froidcour to your front right. Continue through Cheneux and the next villages of Rahier and Froidville to the junction with N66 turning right and pausing immediately upon joining the main road.

At approximately 16:15 on 18 December, as Peiper’s lead tank turned right onto N66 in the direction of the Neufmoulin Bridge, the jeep carrying Captain A.P. Lundberg Motor Officer of the 1111th Engineer Group and his driver ran smack into it. One American died instantly while the Germans shot the other at the roadside.

Continue downhill in the direction of E25 crossing the Lienne Creek at the Neufmoulin Bridge. Pause on the left side of the road on the far bank.

At about 15.00 on 18 December, Sergeants Edwin L. Pigg and Robert C. Billington of the 2nd Platoon, Company A, 291st Engineer Combat Battalion arrived here at the bridge to prepare the structure for demolition. Lieutenant Alvin Edelstein, their platoon leader, joined them shortly afterwards and by 16.00 the 180 foot-timber trestle bridge was ready to be blown. At about 16.45, as the lead Panther turned the bend, Corporal Fred Chapin turned the key and blew the bridge sky-high. The engineers subsequently made good their escape. Note the monument to the 291st, again erected by Emile la Croix and the members of the C-47 club.

Turn around and return back in the direction of Rahier/Froidville taking the second turning to the left marked ‘Chauveheid’. Stop at the small stone bridge in Chauveheid.

At the Neufmoulin Bridge a monument commemorates the role of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion in stopping Kampfgruppe Peiper. (Author’s collection).

When the Americans blew the Neufmoulin Bridge in his face, Peiper ordered halftracks of the 11th Panzer Grenadier Company across the then timber trestle bridge here at Chauveheid. The structure was capable of supporting halftracks but not tanks. Other halftracks of the 10th SS Panzergrenadier Company crossed another wooden bridge at nearby Moulin Rahier.

Carry on to the junction with the main road turning left then as far as the junction with N66. At this junction turn right and drive about 100 yards uphill pausing at the Belgian Touring Club marker on the right side of the road.

Upon crossing the Lienne Creek at Chauveheid, the 11th Panzer Grenadier Company halftracks eventually drove uphill to where you are now where soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, 119th Infantry supported by four M-10 tank destroyers and three 57mm anti-tank guns knocked them out. In radio contact with his Panzergrenadiers, Peiper ordered them back across the Lienne then turned his entire column back through Cheneux to the grounds of the Château Froidcour.

Continue a couple of kilometres further to the village of Werbomont where on the right side of the road in the centre of the village, stands a monument to the ‘All American’ 82nd Airborne Division. Return across the Neufmoulin Bridge and via Froidville and Rahier to the bend by the church in Cheneux. Here on the right side of the road stands a monument to Colonel Reuben H. Tucker’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne.

Upon his withdrawal back through Cheneux, Peiper left fourteen flak guns here in Cheneux to cover his rear. These flak gun crews were later joined by the battered remnants of the 11th SS Panzergrenadier Company after it suffered heavy losses near Stoumont Station. Also in Cheneux were five 105mm guns of the 5th SS Panzer Artillery Battery along with reinforcements of the 6th Panzergrenadier Company of 2nd SS Panzer Regiment who crossed the Petit Spai Bridge and moved to Cheneux in the early morning darkness of 20 December. At midday that same day, Colonel Reuben H. Tucker of the 504th Parachute Infantry ordered Companies A and B of his 1st Battalion to launch a night attack against Peiper’s rearguard in Cheneux.

By 23:00, the defending SS men still held onto the main part of the village having inflicted tremendous losses upon the attacking paratroopers.

At 03:00 on Thursday 21 December, Company G of the 504th attacked Cheneux but made no headway.

At 17:00 that same day, Peiper ordered a withdrawal toward La Gleize and Tucker renewed his attack by the 1st Battalion and Company G.

At 18:30, company G supported by two tank destroyers moved into the main part of Cheneux against light resistance, since by then most of the defending Germans had left the village.

Exit Cheneux in the direction of La Gleize and 1.6 kilometres further on turn left at the crossroads and uphill through the trees. On a bend in the trees, note the stone farmhouse off to your left that served as Peiper’s command post during the attack towards Stoumont. Many of Peiper’s vehicles spent the night here on the grounds of the De Harenne estate. At the junction with the main road (N633) turn left in the direction of Stoumont (not sign posted). A few hundred metres along the road where the Château Froidcour driveway joins N633 from the left note the gatekeeper’s lodge that served as the command post of Sturmbannführer Werner Poetschke’s 1st SS Panzer Battalion during the battle for Stoumont.

As N633 bends to the right leading into Stoumont, keep an eye out for the brick ‘Gendarmerie’ (Polizei) on the left. The half-timbered house after the Gendarmerie existed in 1944 and features prominently in film and photographs taken by German combat photographers during the battle for Stoumont. In this film, German paratroops are clearly seen setting up a machine-gun in the then small field where the Gendarmerie now stands. In that same film, SS-Sturmbannführer Werner Poetschke can be seen turning around to pick up a discarded Panzerfaust anti-tank weapon.

Continue to the church in Stoumont.

On Tuesday, 19 December 1944, a mixed bag of American troops defended Stoumont. They included ten tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, elements of the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 119th Infantry and eight tank destroyers of Company A, 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion as well as three 57mm anti-tank guns in nearby Roua.

At 08.30am, eight or nine German tanks drove straight down the main street into the village as SS Panzergrenadiers, pioneers and paratroopers, moved around the south edge of Stoumont on foot. Reduced visibility enabled German infantry to get in among the tank destroyers and overrun them before they could fire a shot. American tanks were able to evacuate some of the infantrymen while others fled through the woods north of town. Many never escaped and the Germans captured them. Throughout the fighting, many civilians sought refuge in the basement of the ‘Préventorium St. Edouard’, an imposing stone building at the western edge of Stoumont.

Continue west on N633 noting the former ‘Préventorium’ off to your right as the road exits the village. Continue downhill out of Stoumont driving through the next village of Targnon, then passing a hotel on the left and pausing at the bottom of the hill with Stoumont Station and the railroad track on your left.

Panthers approaching the village of Stoumont. The leading tank has received a direct hit.

SS-Sturmbannführer Poetschke commanding the action in Stoumont.

On Tuesday 19 December at around midday, seven Panthers began their descent from Stoumont and after passing through Targnon, withdrew quickly when they came under artillery fire. At the bend several hundred metres past the station, twelve tanks of the US 743rd Tank Battalion, four tank destroyers, a 90mm anti-aircraft gun of Battery C, 143rd AAA Gun Battalion and troops of the 3rd Battalion, 119th Infantry lay in wait for the approaching German column.

Drive toward the bend west of the station and keep an eye out for a Belgian Touring Club stone marker on the left side of N633. Pause here.

Around 14.30 on 19 December, the defending Americans knocked out Peiper’s three lead tanks whereupon Peiper ordered a withdrawal to Stoumont.

Turn around and drive back to Stoumont stopping at the entrance to the village by the driveway to the ‘Préventorium St. Edouard.’

The village of Stoumont falls and its defenders, men of the 119th Infantry Regiment, 30 Infantry Division, surrender. They were eventually released when the Kampfgruppe withdrew a few days later.

Soldiers of the 82nd Airborne Division assemble German prisoners on a forest road. (US Army Signal Corp).

On Thursday/Friday 21/22 December 1944 during vicious fighting in and around St. Edouard, children (including Josette Sarlette an aunt of the author), nuns and l’Abbé C. Hanlet, a Catholic priest, huddled in the basements of the main building as fighting raged around them. By the night of the 21 December, it had become evident to Peiper that he must withdraw from Stoumont and concentrate the remnants of his depleted Kampfgruppe in and around La Gleize. Before first light on 22 December, he ordered the withdrawal taking out his walking wounded but leaving about eighty badly wounded men and several American prisoners in the care of a German medical NCO and two American medics. With tank support and a tremendous artillery barrage, men of the 119th Infantry recaptured Stoumont from a small SS rearguard later that day.

Return to La Gleize and once in the village turn right driving with the church wall to the right of you. Note the ‘December 1944’ museum (www.december44.com) and next to it indisputable evidence of the presence of Kampfgruppe Peiper in the now sleepy village during those turbulent days of late 1944!

This is SS-Obersturmführer Dollinger’s Tiger 213 of the 501st Heavy SS Panzer Battalion, undoubtedly the most impressive relic on the battlefield today.

American GI’s look over two Germans killed in the fighting for Ligneuville. (US Army Signal Corps).

Hopelessly surrounded, out of fuel and low on ammunition, after heavy American shelling on 22/23 December, one of Nazi Germany’s most decorated tank commanders decided the game was up. Peiper requested and was given permission to withdraw; the ambitious attack had failed!

On Sunday, 24 December, he and about 800 of his heavily armed SS men walked out of ‘Festung La Gleize’ in the early morning darkness leaving some 300 more seriously wounded comrades behind in the care of an SS doctor. The withdrawing men, battle weary and exhausted, set out across the icy waters of the Amblève and over the high wooded terrain south of the village. On Christmas Day 1944, the battered survivors of this once powerful fighting unit reached their division command post in Wanne just south of Stavelot.

Suggested Reading:

MacDonald: Chapters 10,11,21 and 22.

Cole: Pages 334-352, 359-377, 599-600

Grégoire Gerard: ‘Les Panzers de Peiper Face À L’ U. S. Army’

Reynolds Michael: ‘The Devil’s Adjutant- Jochen Peiper, Panzer-Leader’

Soldiers of the 463rd Ordnance Evacuation Company load Königstiger 332 onto a tank trailer for eventual transportation stateside as a war trophy. (Courtesy William C Warnock).