DASBURG-CLERVAUX-BASTOGNE-HOUFFALIZE

STARTING POINT: THE OUR RIVER BRIDGE AT DASBURG, 39 KILOMETRES EAST OF BASTOGNE.

German engineers demolished the Our River bridge here at Dasburg during their retreat to the German border in the autumn of 1944. Along with two other bridges at Ouren to the north and Gemünd to the south, this bridge was the only means of access for German armour to exit the Our River valley on their way to the villages sitting astride what came to be called the ‘Skyline Drive’. Villages such as Marnach on the high ground west of the Our dominated roads leading west to Bastogne and beyond and would be defended tenaciously by elements of Major General Norman D. Cota’s 28th Infantry Division and attached units.

German infantry assault troops began crossing the Our River prior to the opening artillery barrage in the pre-dawn darkness of 16 December. At this bridge site, unexpected complications meant that the men of Major Georg Loos’ 600th Engineer Battalion couldn’t begin construction of a replacement bridge until the attack began.

It was at this point that the advance guard of the 2nd Panzer Division awaited the order to advance at dawn 16 December.

It took them until the early afternoon of the first day to complete the bridge at which point impatient tankers of Oberst Meinrad von Lauchert’s 2nd Panzer Division began crossing the Our. Unfortunately, the eleventh tank doing so inflicted severe damage to the structure, which took another three hours to repair. To the south engineers completed the Gemund Bridge at about the same time.

Follow the Clervaux sign from the Dasburg Bridge west to Marnach and pass over the N7. In Marnach, on the bend before the church, on the right side of the street is a monument to the 28th Infantry Division and a plaque to the 707th Tank Battalion.

Men of Company B, 110th Infantry, under their battalion executive officer, Captain James H. Burns, ably supported by a platoon of towed guns of the 630th Tank Destroyer Battalion, fiercely defended Marnach until shortly after nightfall on 16 December. In nearby villages such as Hosingen, Heinerscheid and Munshausen, American infantry and artillerymen did their utmost to stop the German onslaught.

At the western end of Marnach, turn left on route 326 in the direction of Munshausen and pause in front of the village church.

Here, men of Company C, 110th Infantry, supported by six howitzers of the regimental Cannon Company and (on 16 December) by a platoon of medium tanks from the 707th Tank Battalion, inflicted heavy losses on the attacking soldiers of the 2nd Panzer Division’s Reconnaissance Battalion. On 17 December, the gravity of the situation in Clervaux prompted the regimental commander, Colonel Hurley E. Fuller to withdraw the armored support from the defenders of Munshausen. On 18 December, when the Germans finally took the village, they discovered the body of one of their company commanders, on a path near this church with a bayonet stuck in his throat. According to MacDonald, the Germans were so impressed with the marksmanship shown by the defenders, that they nicknamed them ‘The sharpshooters of Munshausen’.

Return to N18 turning left in the direction of Clerf (Clervaux). On the descent into town, pause at the overlook on the right for a spectacular view of the town and its castle.

From here you get a great view of the castle, strenuously defended by soldiers of the 110th Infantry’s Headquarters’ Company under Captains Claude B. Mackey and John Aiken Jr. Five Sherman tanks from a platoon of the 707th Tank Battalion under 1st Lieutenant Raymond E. Fleig, knocked out the lead German Mark IV on a hairpin bend below you effectively blocking this route into town.

Drive down into Clervaux and follow the signs for ‘Bastogne’ keeping the greater part of town off to your left. As you do so, note the GI statue commissioned by C.E.B.A. (a local group which studies the battle) to your left. Park in the next parking lot on the right and below the castle. Cross the street and walk back down the main pedestrian access to the left which takes you back to the GI statue. As you face the statue, note the bronze plaque high on the wall of the bank to your left rear. It depicts the grateful citizens of Luxembourg welcoming their American liberators. Walk up to the castle and in the forecourt pause to look back toward the road that brought you into town. Inspect the Sherman tank and the German 8.8 cm Pak 43/41 then enter the inner courtyard to visit the Ardennes Battle Museum, open in June from 13:00 till 17.00 then in July till 15 September from 10.00 till 17.00. On Sundays and holidays (including Christmas) the museum opens from 13.00 till 17.00 and is closed throughout January and February.

Return to your car and continue in the direction of Bastogne crossing the railroad. Note the Claravallis hotel to your left and the rock face to its rear. Pause here.

An American GI outside the Bertemes cafe/gas station in Marnach, examines abandoned German weaponry. (US Army Signal Corps).

Clervaux after the battle. The castle was strongly defended by men of the 110th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division. (US Army Signal Corps).

This building served as regimental headquarters of Colonel Fuller’s 110th Infantry Regiment. On the evening of 17 December, German tanks entered Clervaux from the north, crossed the railroad and opened direct fire upon the hotel. Colonel Fuller and some of his staff escaped up the rock face to the rear of an upstairs room only to be captured later on their way west of the town. At 18.39, the sergeant at the regimental switchboard called division to report that he was alone- only the switchboard was left.

Follow N18 in the direction of Bastogne until you reach the Antoniushof traffic island on N12.

By the evening of 17 December, the VIII Corps commander, Major General Troy H. Middleton, faced the problem of having insufficient numbers of men with whom to stop the German advance west of Clervaux. He ordered Colonel Joseph H. Gilbreth of Combat Command Reserve, 9th Armored Division, to place roadblocks here and at the next important junction at Fetsch. Here, at Antoniushof, Captain Lawrence K. Rose of Company A, 2nd Tank Battalion, positioned his task force comprising his own tank company, a company of armored infantry and an engineer platoon supported by a battery of guns from the 73rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. Reconnaissance troops of von Lauchert’s 2nd Panzer Division first approached Antoniushof on the morning of 18 December only to be followed that afternoon by tanks and armoured infantry. Under pressure after losing their artillery support, Task Force Rose withdrew from Antoniushof later that evening in the direction of Houffalize.

Turn left on N12 and drive on until you reach the junction with N874 sign posted ‘Bastogne’. This is Fetsch.

Here, a second armored task force of Combat Command Reserve, 9th Armored Division, under Lieutenant Colonel Ralph S. Harper, established a roadblock comprising a company of tanks, a company of armored infantry and two batteries of the 73rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. German tanks overran Task Force Harper, killing Colonel Harper whose infantry and few surviving tanks raced west to Longvilly. Colonel Theodore Seeley and men of the 110th Infantry tried in vain to stop the Germans who captured them.

Drive west on N874 to Longvilly stopping at the church.

Rather than proceeding into Longvilly, 2nd Panzer Division turned northwest in the direction of Bourcy. Von Lauchert’s objective was not to capture Bastogne but rather to cross the Meuse River as quickly as possible. This gave Colonel Gilbreth and the remnants of Combat Command Reserve, 9th Armored Division, the time for a short-lived and much needed breathing space. Longvilly, five and a half miles from Bastogne, was the scene of considerable confusion. Stragglers rode or marched through the dingy village and no one seemed to know the precise location of the oncoming Germans, although rumour placed them on all sides. By 18 December, General Middleton was doing all he could to block the roads into Bastogne. Combat command B, 10th Armored Division under Colonel William Roberts, set up its command post at the hotel Lebrun just off the main square in Bastogne. From there he dispatched three combat teams to block three of the seven roads leading into the threatened city. Team Cherry, under Lieutenant Colonel Henry T. Cherry set up its headquarters in the village of Neffe just east of Bastogne on the evening of 18 December. Its advance guard under 1st Lieutenant Edward P. Hyduke continued east to the western edge of Longvilly to assume defensive positions north, south and east of the village. By 19.00, the main body of Team Cherry under Captain William F. Ryerson was assembled on the road about a thousand yards west of Longvilly. Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein’s Panzer Lehr, bypassed Longvilly to the south and captured Magaret, the next village to the west thus cutting the road to Bastogne. During the night, small groups of Germans made feeble attempts to pick off American vehicles crowding the streets of Longvilly. At Midnight in his command post in Neffe, Colonel Cherry learned that the Germans had captured Magaret thus separating his headquarters from the rest of the team here in Longvilly.

Continue west through the village until you reach the ‘Grotto of Notre Dame’ on the left side of the road. Stop here and note the bullet and shell fragment damage to the iron gates in front of the grotto.

Here, a force comprising Lieutenant Hyduke’s remaining light tanks, armored cars and a platoon of tank destroyers from the 811th Tank Destroyer Battalion, managed to hold their ground for over an hour until Colonel Cherry ordered them to fall back and join the rest of the unit. Destroying their remaining vehicles, Hyduke’s men began walking cross-country to the west.

Drive towards Magaret, stopping on the slope leading down into the village.

This stretch of road is where the Germans destroyed the bulk of Team Cherry’s vehicles with tank, artillery, antitank and rocket fire leaving a mass of twisted steel in its wake.

Drive into Magaret stopping where a sign points right in the direction of Bizory.

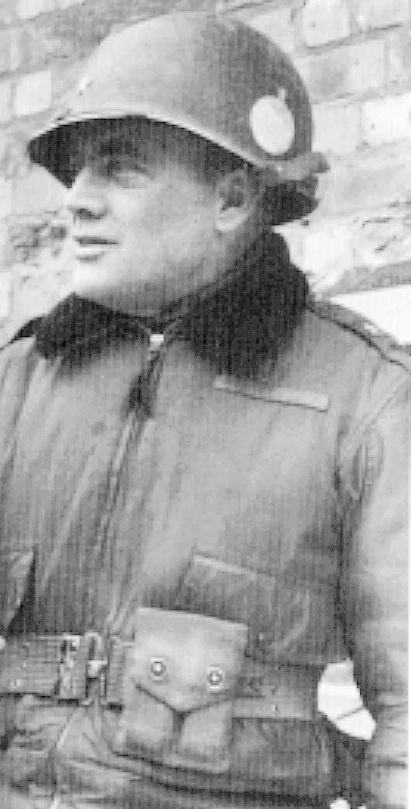

Oberst Meinrad von Lauchert commander 2nd Panzer Division (Author’s collection courtesy General von Lauchert).

As Task Force Harper had struggled to defend Fetsch, Bayerlein’s Panzer Lehr bypassed Fetsch through Oberwampach at which point, it was less than six miles from Bastogne. In Oberwampach, he sent a small force of tanks and panzergrenadiers to reconnoitre a minor road leading directly to Magaret only three miles from Bastogne. Despite the poor quality of this road, Bayerlein’s advance guard captured Magaret shortly after the passage of Team Cherry on its way to Longvilly. Uncertainty as to the strength of the American unit now to his rear, caused Bayerlein to call a temporary halt to his advance upon Bastogne.

Drive into Neffe turning left at the stone chapel in the direction of Mont. Pass the first farm on your left and past the curve cross a small bridge. Up ahead, just before the road branches to the right, stands a farmhouse. Pause here.

This farm stands on the former site of Colonel Cherry’s command post, the Château de Neffe. As the bulk of his team fought for its life at Longvilly and Magaret, Colonel Cherry and his staff were having a fight of their own here at the command post in Neffe, a mile and a quarter southwest of Magaret. Cut off from his main force, through the small hours of the 19 December, Cherry and his staff eagerly awaited reinforcements from the incoming 101st Airborne Division. At first light, a detachment of tanks and infantry of the Panzer Lehr hit the American tank platoon holding the crossroads in the centre of Neffe. The defenders stopped one tank with a bazooka round, but then broke under heavy fire and headed west along the road to Bastogne. One of the two American headquarters tanks in support of the roadblock got away, as did a handful of infantrymen who fell back to the château.

Just before noon, the Germans moved in to try and clear the stubborn defenders from the command post. Cherry’s men held fast for over four hours using the automatic weapons lifted from their vehicles, and checking every enemy rush in a hail of bullets. Ultimately, a few determined Germans set the building alight when they threw incendiary grenades through the windows. A platoon of the 501st Parachute infantry arrived just in time to take part in the withdrawal. Their appearance and the covering fire of other troops behind them jarred the Germans enough to allow Colonel Cherry and his staff to break free. Before pulling out for Mont, the next village to the southwest, Colonel Cherry radioed his commander Colonel Roberts the following message:

‘We are pulling out. We’re not driven out but burned out!’

Turn right, then keep left continuing straight ahead and eventually crossing N84 in the direction of Marvie and stopping by the village church. Note the turret by the community center on your right.

Here, yet another element of Colonel Roberts’ Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division, Team O’Hara, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James O’Hara, took up positions near Marvie aimed at blocking the road into Bastogne. On 20 December, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division, sent a battalion of his glider infantry to relieve the tired and hungry soldiers of Lieutenant Colonel Paul H. Symbol’s under strength 35th Engineer Combat Battalion near Marvie. The changeover completed, one of O’Hara’s outposts spotted a German column comprising four tanks and a rifle company approaching the village. Within one hour, O’Hara’s medium tanks had accounted for the panzers and the glider infantrymen had beaten back the German infantry in disorder and occupied Marvie. In vicious close quarter fighting on 23 – 24 December at different times both sides claimed to have control of the village. This may well have led to an American air strike against Marvie by P-47’s during the afternoon of 24 December. Much of the village burned as a result of these attacks but nonetheless the defenders kept hold of the western edge of the village.

Drive into Bastogne straight up N84 until you reach the tank on the central square today named ‘Place McAuliffe’. Follow the sign for Liège (E25) and on E25 take exit 53 marked ‘Hemroulle’. Drive into the village and stop by the church.

Brigadier General Gerald J. Higgins acting Deputy Division Commander of the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne. (US Army Signal Corps photograph courtesy General Higgins).

On 23 December, at a drop zone west of Bastogne between Hemroulle and Mande-Saint-Etienne, 241 C-47 aircraft dropped 144 tons of supplies, mainly artillery ammunition to the encircled defenders of Bastogne who, by then, were down to their last few rounds.

At one point in the fighting here, the defenders found themselves lacking suitable camouflage material. Major John D. Hanlon and a village councillor went from door to door asking the occupants for white sheets with which to camouflage the American vehicles. Hanlon returned post-war, bringing with him, a pair of white sheets for every home in the village, a gift from the people of his hometown in the United States.

Drive through Hemroulle in the direction of Champs, stopping with a narrow, blacktop road leading right in the direction of ‘Rolley’ and at the time of writing a few large trees on your left.

American vehicles approach the market square in Bastogne from the rue d’Assenois. (US Army Signal Corps).

On Christmas Day and 26 December 1944, elements of Generalmajor Heinz Kokott’s 26th Volksgrenadier Division, supported by Kampfgruppe Maucke of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division, made a final desperate bid to break into Bastogne. A group of eighteen Mark IV tanks with Volksgrenadiers riding ‘piggy-back’ broke through the lines of Companies A and B of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment. Just west of Hemroulle, about half the tanks wheeled left, defiling along a narrow cart path which led to the Champs to Bastogne road on which you are now parked. As they approached the road, the panzers formed in line abreast, now bearing straight toward Companies B and C of the 502nd Parachute Infantry, who were on their way to bolster the defenses at Champs. Lieutenant Colonel Steve Chappuis, commanding the 502nd, had but a few minutes to face his companies toward the oncoming tanks. Two tank destroyers of Company B, 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion, absorbed the initial shock before the Germans knocked them out as they fell back toward the Champs road. As the panzers rolled forward, Company C made an orderly withdrawal to the edge of a large wood on the east side of the road between Champs and Hemroulle. The paratroopers showered the tanks with lead, and the infantry clinging to the decks, fell to the snow covered ground. The tank detachment again wheeled into column, this time turning north toward Champs. Two of the other 705th Tank Destroyers that were supporting Company C caught the column in the process of turning and put away three of the panzers; the paratrooper’s bazookas accounted for two more.

A burned out American M18 tank destroyer on the outskirts of Bastogne. (US Army Signal Corps).

Fire from American tanks, tank-destroyers, parachute field artillery and bazookas decimated the half of the enemy tank-infantry formation which had kept on toward Hemroulle after knifing through the 327th foxhole line, effectively ending this German foray behind the American lines.

Turn right down the narrow road leading to Rolley and stop in front of the château.

This building served as the regimental command post of Lieutenant Colonel Steve Chappuis’ 502nd Parachute Infantry.

Return to the main road and turn right in the direction of Champs. In the centre of the village, turn left in the direction of Mande-Saint-Etienne (not sign posted at the time of writing but spot marked by a cross commemorating military and civilian victims of both wars).

Drive uphill leaving the sign for Flamierge off to your right and return via Mande-Saint-Etienne to Bastogne.

In Bastogne, at the tank on Place McAuliffe, take N85 in the direction of Neufchâteau. Cross over E25 and in Sibret, turn left following a sign for Homprè. Pass under E25 then take a left stopping immediately alongside the Belgian war memorial facing the hamlet of Clochimont.

On 18 December 1944, General Omar N. Bradley commander of 12th Army Group, called the Third Army Commander Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. to his Luxembourg City headquarters in the Hotel Alpha near the railway station. At this meeting, Patton first learned of the potentially catastrophic situation facing First Army to his north. When asked what help he could give, the Third Army commander immediately replied that he could intervene with three divisions ‘very shortly’. He telephoned the Third Army chief of staff to stop the XII Corps attack forming for the following day and to prepare the 4th Armored and 80th Infantry Divisions for immediate transfer to Luxembourg.

By nightfall on the 18th December it became apparent that the First Army situation had deteriorated beyond expectation and at about 02.00 on 19 December Bradley called Patton to a meeting in Verdun later that morning for a meeting with the supreme commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower. At midnight the 4th Armored division began moving north to Longwy and at dawn the 80th Infantry Division started for Luxembourg City.

In anticipation of the tremendous difficulties this mission would entail, Patton ordered his Third Army Chaplain to compose the now legendary Weather Prayer:

THE WEATHER PRAYER

Almighty and most merciful Father, We humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have to contend. Grant us fair weather for Battle. Graciously hearken to us soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory, and crush the opression and wickedness of enemies, and establish Thy justice among men and nations.

Amen.

It was from close to this spot, at 15.00 on the 26 December 1944, that Lieutenant Colonel Creighton W. Abrams 37th Tank Battalion and Lieutenant Colonel George L. Jaques’ 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion intended to attack in the direction of Sibret. As both commanders pondered their next move, they spotted C-47 aircraft dropping supplies to the encircled defenders of Bastogne. Colonel Abrams then made a momentous decision and proposed they break through to Bastogne via Clochimont and Assemis, Jaques agreed.

General Creighton W. Abrams who, as a Lieutenant Colonel Commanded the 37th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored Division. Along with men of the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion. This unit broke the siege of Bastogne. (Author’s collection courtesy General Abrams).

At 15.20, Abrams radioed Captain William Dwight the battalion Operations Officer to bring forward the ‘C-Team’ comprising tanks of Company C of the 37th and halftrack-borne infantrymen of Company C of the 53rd. Another message, this time through an artillery liaison officer, gave the plan to the supporting 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion and asked that someone tell the 101st Airborne that the armour was coming in. The 94th was already registered to fire on Assenois, but there was little time in which to transmit data to the division artillery or arrange a fire plan, Combat Command Reserve, alone among the 4th Armored Combat Commands, had no wire in. Continuous wave radio could not be counted on. Frequency modulation was working fairly well but they would have to relay all messages. Despite these handicaps, in fifteen minutes three artillery battalions borrowed from Combat Command B, (the 22nd, 253rd and 776th) were tied in to Shell Assenois when the call came.

Start driving through Clochimont towards Assenois stopping a few hundred yards short of the village.

Colonel Abrams had entrusted Captain Dwight with the breakthrough telling him ‘It’s the push!’ By 16.20 all was ready and the ‘C-Team’ moved out, Shermans in the lead, and halftracks behind. Abrams stayed glued to his radio. At 16.34, he checked with the 94th Field Artillery Battalion to ask if he could get the concentration on Assenois at a minute’s notice. Exactly one minute later, Lieutenant Charles P. Boggess called from the lead tank. Abrams passed the word to the supporting artillery. ‘Concentration Number nine, play it soft and sweet.’ A ‘Time on Target’ massed fire could hardly be expected given the state of communications, but the supporting thirteen batteries sent ten volleys crashing onto the drab village.

Eight German anti-tank guns ringed the village and fired a few wild shots before suffering direct hits from incoming artillery rounds or losing their crews to machine-gun fire from the tanks.

Drive to the dip on the road at the edge of Assenois. At this point, Lieutenant Boggess called for the artillery to lift, then plunged ahead without waiting to see if the 94th gunners had received his message.

Enter the village.

So close did the attack follow the artillery, that not a hostile shot was fired as the tanks raced into the streets. The centre of the village was almost as dark as night, the sun shut out by smoke and dust. Two tanks made a wrong turn. An incoming American shell knocked out one of the infantry halftracks since the initial fire plan had called for the supporting 155mm battery to plaster the centre of town and these shells were still coming in as the halftracks entered the streets. Far more vulnerable to the flying shell fragments than the tankers, the armored infantrymen leaped from their open vehicles and into the nearest doorway or behind a wall. In the smoke and confusion, the German garrison, a mixed group from the 5th Parachute and 26th Volksgrenadier Divisions, poured out of nearby cellars. The ensuing shooting, clubbing, stabbing melee was all that the armoured infantrymen could handle and the C-Team tanks rolled into the pages of U.S. Military History alone.

Drive straight on uphill to the Northeast until (at the time of writing) you reach woods on the left, pause here.

Sergeant John H. Parks of Mill Creek, Indiana as photographed on 10th December 1944 by a member of the 166th Photo Signal Company. Sergeant Parks served as a tank commander in the 2nd Platoon, Company B, of the 37th Tank Battalion. He died in action 23 December when the 37th engaged elements of the 5th Fallschirmjäger Division in Luxembourg during its drive to relieve the surrounded defenders of Bastogne. His remains were never recovered or positively identified and he was listed as ‘Killed in Action/Body not recovered’. His name is inscribed on the Wall of the Missing at Luxembourg Military Cemetery. (US Army Signal Corps).

The relief column now consisted of three Shermans led by Lieutenant Boggess, followed by a halftrack that had blundered into the tank column and two more Shermans bringing up the rear. Boggess moved fast, his machine-gunner liberally spraying the woods on either side beside the road. A 300 metre gap developed between the lead three tanks and the last three vehicles giving the Germans time to lay a few Teller mines in front of the halftrack. The halftrack rolled over the first mine and exploded. Captain Dwight then rolled his two tanks onto the shoulder, the crews removed the mines, and the tanks raced on to catch up with Boggess.

Drive on a few hundred yards passing a minor road to the left (at the time of writing a recycling plant is on the right) and until you spot a group of decorative evergreens to your front right and a large open field on the left. Stop by the evergreens.

At exactly 16.50 on 26 December 1944, Lieutenant Boggess spotted some soldiers in friendly uniform preparing to assault the concrete pillbox now to your right. They were men of the 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion holding the defensive perimeter of Bastogne. His gunner fired three quick rounds at the pillbox and its German occupants surrendered. The relieved engineers rushed forward to greet their liberators and very soon thereafter General McAuliffe came to meet Captain Dwight. Back near Clochimont, Colonel Abrams received a message from his commander, Colonel Wendell Blanchard asking what he thought of the possibility of breaking through to Bastogne.

The Belgian army pillbox on the outskirts of Bastogne, named in honour of Lieutenant Charles P. Boggess 37th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored Division. Evidence of battle damage can still be seen when his tank opened fire on this German held position.

By midnight on 26 December, 4th Armored had a secure hold on the road into the city.

Continue in the same direction turning left at the first sign for Bastogne. Upon reaching the main road, turn right in the direction of Arlon (N30) take the first exit at next traffic circle and at the sign for Lutremange, keep front left passing the tank turret and the ‘Notre Dame de Bonne Conduite’ chapel on your left. Continue downhill and over the next small ridge, stopping before the old farm on the left. Across the fields to your right rear, the building next to the metal barn was the Kessler farmhouse, to which German emissaries brought their now famous surrender demand.

On 22 December, four German emissaries, including two officers, came walking up the road from Remoifosse to Bastogne carrying a flag of truce. Soldiers of Company F, 327th Glider Infantry, took them to the farmhouse, then serving as command post of the company’s Weapons Platoon. Eventually, a Major from Battalion took the terms to the division command post then in the Heintz Barracks in Bastogne. Colonel Joseph H. Harper, commanding the 327th Glider Infantry of the 101st Airborne, received a radio message ordering him to report to General McAuliffe. When Colonel Harper reached the Heintz Barracks, he reported to a basement room, at that time being used by the headquarters clerks for typing. General McAuliffe showed him a sheet of paper with the word ‘N-UT-S’ typed in the centre. Colonel Harper thought the response amusing and asked the general if he could be the one to deliver the response to the Germans.

Major General Joseph H. Harper who as a Colonel, commanded the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne. (US Army photo courtesy General Harper).

General McAuliffe.

In a letter to the author dated 3 August 1969, Major General Joseph H. Harper recalled his memories of events at the Kessler farmhouse:

‘The Germans were waiting, still blindfolded, in the Company F command post, a Major and a Captain (actually a lieutenant). The Major, in a rather condescending manner asked “Is the reply in the negative or the affirmative? If in the affirmative, then we have the authority to negotiate further your surrender.” The Germans’ whole attitude and their assumption that we would consider surrendering made me angry. I replied “It is decidedly not in the affirmative” and added “If you continue this foolish attack, your losses will be tremendous.”

‘I then had them led to my jeep and took them back over a meadow road to the outpost where they had first entered our lines. Upon arrival, I told them to remove their blindfolds. I then said, “You will probably not understand what the word (Nuts) in the message means. It means the same as ‘Go to Hell’” and stated further “‘I want you to understand something else. If you continue to attack, we will kill every goddam German that tries to enter into this city.” The Captain translated, they both turned red, saluted and said “This is war, we will kill many Americans.” I returned their salute and said “on your way Bud”, then, through a slip of the tongue added “Good luck to you”. I of course, regretted this last remark.’

Return to Bastogne and park on the main square (Place McAuliffe). The square features a bust of General McAuliffe, a Sherman tank knocked out during the battle, and plaques honouring the 101st Airborne Division, 10th Armored Division and the 406th Fighter Group. Just off the square, on the right side of the Route Du Marche, stands the former Hotel Lebrun (at the time of writing a reclad non-descript building to the left of the current Hotel Giorgio), which served as the command post of 10th Armored Division’s Combat Command B under Colonel William Roberts. To the south of the square on the Avenue de la Gare is the 101st Airborne Museum (www.airbornemuseumbastogne.com).

Exit the car park and drive east in the direction of the ‘Mardasson’, a star shaped monument dedicated on 4 July 1946 in honor of the United States and its role in the liberation of Belgium. Upon leaving the main road and turning left for the Mardasson, note the Belgian pillbox on the left, and the memorial named after Corporal Emile Cady, the first Belgian soldier killed in the defense of Bastogne in 1940. Continue around the bend then pause where the road splits in two, note the cone-shaped stone marker. This is the final stone of the ‘Liberty Way’, a series of such markers on the route between the Normandy Coast and Bastogne marking the advance of American troops inland after D-Day.

Contine up this road and park on the historical centre car park. (www.bastognehistoricalcenter.be/)

All around the town of Bastogne tank turrets symbolize and mark the defensive perimeter. (Author’s collection).

The various tank turrets scattered around the city symbolise the tenacious defense of the encircled garrison by American troops during the battle.

Upon re-entering the city, at the first major intersection turn right in the direction of Houffalize, then take second exit at traffic circle down Route de la Roche in the direction of E25. The red brick buildings opposite the town cemetery, are the Heintz barracks (40 Route de la Roche), a Belgian army barracks, which served as the 101st Division command post during the siege.

Return to the N30 (main road towards Noville/Houffalize). In the village of Foy, turn right and Southeast in the direction of Bizory. Stop just before the road enters the trees of the Bois Jaques.

On the right side of the road (at the time of writing just inside the trees ahead of you, the traveller can still spot foxholes of the 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry, immortalised in the book Band of Brothers by Stephen E. Ambrose.) Initially, the 506th attempted to attack the high ground to the North and overlooking Noville in support of Team Desobry, another of the Teams of Colonel Roberts’ Combat Command B. However, they and the remnants of Team Desobry had to fall back to Foy under massive German pressure from the North. They then fell back to here to form the northern edge of the defensive perimeter around Bastogne. In his book Seven Roads to Hell Donald Burgett graphically describes his experiences in Noville as a member of the 1st Battalion 506th and the subsequent withdrawal to Foy.

Continue through the woods stopping at the far side just before reaching the old railroad line.

As a member of the 3rd Platoon, Company A of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, Lieutenant Robert I. Kennedy served as assistant platoon leader. In a letter to the author, Bob Kennedy spoke of his experiences during the battle here in the Bois Jaques.

‘On the evening of 19 December, the 2nd Battalion was unable to make contact with the 506th Regiment along the railroad track running from Bastogne to Bourcy, which was the boundary between the 506th and 501st. The Germans evidently probed the area and found a large gap existed there. Company A of the 501st quickly pulled out (of its original position on the outskirts of Neffe) and went down the tracks to close that gap. As we approached the far edge of the woods located about 300 yards west of where the Bizory-Foy road crossed the railroad tracks, we hear the Germans coming straight at us. We deployed at the edge of the woods and waited until they were within yards of us. They wore white snow camouflage and we opened up with everything we had. When the fog lifted and daylight came, the open field in front of us was covered with German dead. We picked up several prisoners and had a few casualties of our own. The rest of the enemy withdrew to their own lines. No one told us that the Germans had surrounded us and captured the Division hospital. I made a trip to the chapel in the Bastogne seminary to visit the wounded from our company. Wounded and dying soldiers covered every square foot of floor space while only a few medics and sisters helping them, pretty much confirmed these rumours. Normally most of these men would have been evacuated to the rear. The piles of frozen bodies in the courtyard would also have been removed had the roads to the rear been open. On the return trip to the unit, I passed a huge circle of massed artillery facing outwards and firing in every direction of the circle. At night, you could see flashes of heavy gunfire in the distance to your left and right. You knew then, that you were surrounded. We didn’t worry much about being surrounded because in airborne missions you are always surrounded. We did begin to worry about supplies since we weren’t getting too much food or ammunition but we knew that eventually we would get an airdrop. On 23 December, the sky cleared, the sun came out, the first time we had seen blue sky. This alone raised the morale of the troops, and then in the middle of the morning came the planes. Hundreds of C-47’s and fighters, it was one of the most spectacular sights I had ever seen. The sky was filled with coloured supply chutes and the fighters were buzzing the perimeter at treetop level. It must have been a terrible sight for the Germans.’

Return to the western edge of the woods making a brief pause overlooking the road into Foy.

In Noville, the house used as Major Desbory’s command post still stands. (Author’s collection).

First Lieutenant Harry E. Krig, a fighter pilot with the 513th Fighter Squadron returned to Foy on 21 September 2000. This was his ‘trip of a lifetime’ organised by his wife Pat and during which the author had the great privilege of tagging along. In an article entitled ‘My Bastogne Story’ Harry spoke of his first visit during which he got shot down in the vicinity of where you are now:

‘In December, 1944 I was a pilot stationed in Mourmelon, France, a small town in close proximity to the Belgian, Luxembourg and German borders. Our headquarters was close to a 101st Airborne (paratrooper) base. Around December 16 news of the Battle of the Bulge reached us. Soon stories were told of Allied units being surrounded and Germans behind the lines in U.S. uniforms who were taking no prisoners as they advanced across Belgium. The 101st moved out to Bastogne to hold the town and its strategic roads.

‘The weather was bad and extremely cold. I remember early morning briefings and then sitting around all day, grounded because of low ceilings, fog or snowstorms. I was flying a P-47 Thunderbolt and my flying log shows I flew missions on December 17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 and 30. This story is about the December 30 mission.

‘We were scheduled to attack a tank column on the road to Bastogne. We were told to expect the tanks to be painted white as camouflage against the snow, and to be prepared for heavy anti-aircraft fire (flak). Our first flight went in, meeting heavy flak as expected. My flight, the second, was advised to avoid the flak by approaching from behind a wooded rise.

‘As my turn came, I flew in so low that I remember my propeller ticking the treetops. To make my rocket firing run, I had to pull up to get a dive angle. I sighted on a white tank, fired, and then pulled up in a turn to avoid flying through the explosion. My exposed plane received hits in the engine and left wing and I knew I should bail out.

‘We had been told US troops held a one-mile area surrounding Bastogne and we were instructed to bail out there, if possible. Bastogne was immediately to my left so I turned in that direction and pulled up. My engine quit and was on fire. Heavy black smoke was coming back over the cockpit. A large jagged hole was in my left wing and I could see ammunition belts hanging from the hole.

‘The procedure for bailing out was to open the canopy at the lowest possible speed, trim the aircraft to level flight, and place your feet on the seat and dive toward the trailing edge of the right wing. I did all of this except for slowing the aeroplane. There wasn’t time. As I stood up to make my dive the slipstream pinned me to the rear of the cockpit. I clawed my way out, slid down the side of the fuselage, and hit my left leg on the horizontal stabiliser of the tail section. I tumbled violently and had trouble getting hold of the ‘D’ ring to deploy my parachute. My altitude was no more than 500 to 600 feet and I remember the feeling of panic as I grasped the ring and pulled. Oh, how I pulled!

‘I felt the shock of my parachute opening and just as I looked down, my feet touched the snow-covered ground. I realised my left leg was completely numb and useless as I extracted myself from the parachute harness. I rose to my hands and knees, looking around trying to figure out if I had landed in the safe area. I heard voices but could not distinguish the language. I ducked back down in the snow and covered myself with my white parachute.

‘I eventually peeked out and saw a U.S. Army Medic standing at some distance, probably 250 yards away, waving at me from a grove of trees. Unable to walk, I started to crawl through the snow, trying to remain concealed under the parachute. It became too difficult to drag and I gave up on it. As I approached the tree, the Medic and another soldier ran out, grabbed me under the armpits and dragged me into the grove. They took me to a foxhole covered with logs and threw a blanket over me. Just then, we came under a mortar barrage. I remember the Medic saying, ‘Oh, shit they saw us.’ Suddenly, I had lots of company in the foxhole. After a time the shelling stopped but the noise continued as the Americans returned fire. My rescuers were from the 101st Airborne – friends from Mourmelon!

‘I had bailed out in mid-morning and as the day wore on, pain replaced the numbness in my leg. I was wet from crawling through the snow and so cold I was shivering violently. The Medic returned and gave me a shot of morphine for the pain. He told me they would get me to a field hospital that evening. We talked some of the battle. He asked me if I would give him my .45 calibre pistol. Medics were not allowed to carry firearms, but, he said, in this battle no prisoners were being taken and Medics were unprotected. I did not say yes or no. He brought me a rifle in case of attack and pointed in the direction of the enemy. I noticed his finger pointing right down the furrow in the snow I made while crawling.

‘Several times that afternoon we came under enemy mortar fire. Finally, darkness came and we travelled in a jeep into Bastogne. The hospital, a former church, had been hit and one side of it was covered with a tarp. My medic friend found a place for me among the patients lying in rows on stretchers. As he started to leave, I handed him my pistol.

‘The hospital, treating both military and civilians, had a brightly-lit operating room at one end screened off with a tarp. There was continual activity there all night. My leg continued to swell and during the night I asked an attendant to slit my pant leg to relieve the pressure. Another shot of morphine enabled me to sleep.

‘The next day I spent in a corner out of the way – a broken leg was, under the circumstances, a minor wound. I remember eating a cracker and cheese from a can as lunch. I learned I was to be evacuated by ambulance that night.’

First Lieutenant Harry E. Krig, Fighter Pilot with the 513th Fighter Squadron. German anti-aircraft gunners shot down Krig’s plane on 30 December 1944 near Foy. (Author’s collection, courtesy Harry Krig).

Upon evacuation, Lieutenant Krig learned that he was to be flown to England, so rather than leave his buddies at the 513th, he bribed the pilot of a small observation plane to fly him back to the squadron at Mourmelon.

Return to Foy, crossing the main road (N-30) and following the sign for the German War Cemetery at Recogne. It can be found a few hundred yards past the local civilian cemetery on the left side of the road to Recogne.

On 4 February 1945 American Graves Registration began laying out a large collecting cemetery on this site. They buried some 2,700 Americans and 3,000 Germans in two separate plots. In1946/47 they either repatriated the American dead or moved them to Henri-Chapelle and the Belgian authorities turned this into a permanent German cemetery holding 6,804 Germans soldiers. In 1984, the Belgian and German governments reached an agreement placing the care of German war graves in German hands.

Return to N-30 turning left in the direction of Noville. Upon reaching the village stop by the bus stop and the fourth house on the left.

Recogne German war cemetery. (Author’s collection).

Team Desobry of Colonel William Roberts’ Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division, under Major William Desobry, supported by a tank destroyer platoon of the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion rushed to defend Noville. Reinforced by the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 506th Parachute Infantry, they tenaciously held the village until ordered to withdraw to Foy on 20 December. In his first-hand account of the bitter fighting here, entitled Seven Roads to Hell Donald R. Burgett graphically described their defence of the village in the face of attacks by German tanks and infantry. He placed particular emphasis upon the effects of artillery.

‘Artillery is the most horrible, death-dealing, feared instrument of modern war. More men have been wounded, maimed, or killed by artillery than by any other means since the advent of gunpowder. When you are being pummelled by artillery there is nothing you can do to strike back. All you can do is lie there and listen to the shrieking, screaming shells coming in and the loud explosions they make when they hit. Your throat dries up and your lungs burn as you breathe in the burnt powder, dust and acrid smoke caused by the blasts. You instinctively hug the ground as hot, ragged fragments and splinters of shrapnel tear into trees, stone walls and human bodies. There is nothing you can do to fight back, while all around you flesh is being torn to red, bloody scraps.

Some men pray, some yell at the enemy and some just lie there quietly, in their holes, being bounced and jarred around while they await their fate. At times under heavy, prolonged shelling I found myself yelling, screaming at the enemy to stop. I would scream for the shelling to stop, for the enemy to come out face-to-face with us and get it over with. On the other hand, when it was our shells rumbling overhead toward the enemy, I would yell, “Give it to them! Don’t stop until you’ve killed every goddamned one of them”.*

* By kind permission of Donald R. Burgett and Presidio Press

This building, outside which you have stopped served as the joint command post of Team Desobry and Lieutenant Colonel James L. LaPrade’s 506th Parachute Infantry.

During night fighting here in the centre of Noville a shell burst inside the building killing Colonel LaPrade and wounding Major Desobry. German troops captured the ambulance evacuating the unfortunate Major to Bastogne. He regained consciousness only to discover his newfound status as a Prisoner of War.

Drive north to Houffalize and upon descending into town note the Panther tank of Colonel Gerhard Tebbe’s 16th Panzer Regiment of the 116th Panzer Division, a unit later decimated in the Verdenne Pocket.

Continue downhill into the centre of town turning left in the direction of Laroche and pause by the church, next to which is a monument commemorating civilian victims of the town’s bombing by the RAF.

Continue out of town in the direction of Laroche and approximately 7 kilometres out of town turn left on the first road bridge crossing the Ourthe River, signposted Engreux. Upon crossing the bridge, park by the rock face on the far bank. Note the plaques commemorating the junction of First and Third Armies close to here on 16 January 1945, effectively cutting off the Bulge in the American lines.

Return to the main road turning left in the direction of Laroche. Park in the town centre.

Here in Laroche, there is evidence of the British role in the battle since elements of the British 51st Highland Division entered the town on 11 January 1945 to link up with their American counterparts, from Company C, 635th Tank Destroyer Battalion attached to the 4th Cavalry Group. A US Army Signal Corps photographer immortalised this moment when he took a photograph of the link up. In recent times, Mr. Henri Rogister of CRIBA and Mr. Guy Blockmans of the Belgian Office for the Promotion of Tourism have helped identify the individual soldiers in the photograph. They have also managed to get eyewitness accounts from men in both units:

The Achilles at Laroche. (Courtesy OPT).

Carl Condon of Bismarck, Maryland served with Company C of the 635th and spoke of this picture:

‘We were the 635th Tank Destroyer Battalion attached to the 4th Cavalry at that time. The 84th Infantry division was also in Laroche. I remember the town very well but was not aware that the picture existed. All of these Americans were our men from Company C. First Sergeant Ray Spangler of Topeka, Kansas, Corporal Harlen Mathis of Minneapolis, Minnesota and Staff Sergeant Max Beal of Coffeyville, Kansas.’

On the British side, Harris McAllister remembers the linkup:

‘The picture of Corporal John Donald Sergeant F.D. ‘Ricky’ Richards and myself was taken after the capture of Laroche. We crossed over the wrecked/blown up bridge over the Ourthe River and met the American soldiers in an armoured car. We sat down and had coffee provided by them, round a fire of petrol and sand in a bucket in front of a garage. It was then that the photographer arrived with a reporter in a jeep and took a photograph of us. He realised we had different uniforms, and this was the Allied linkup. He then asked us to meet at the corner of Rue de la Gare and Route de Cielle and shake hands, which we did and he took a second, more appropriate photograph.’

Soldiers of US First and Third Armies join forces at Rensiwez, 16 January 1945.

The posed link-up at Laroche. (Courtesy OPT).

The Link-up plaque. (Courtesy of OPT).

Today, at the same spot, a marble plaque commemorates the incident while above town an ‘Achilles’ tank destroyer and other monuments recognise the role of British troops in the vicinity.

In a letter to the author dated 7 January 1979 the former XXX Corps Commander, Lieutenant General Sir Brian G. Horrocks spoke of the personality clashes between his boss Field Marshal Montgomery and his American counterparts:

‘When the battle was over, he (Montgomery) stood up on the stage and told the audience how he had won the battle. This did not make for happy co-operation between the British and the Americans because the Battle of the Ardennes was won by the extreme gallantry of young American soldiers.’

In town there is also an interesting Bulge museum run by Mr. G. Bouillon the address for which is:

Musée Bataille Des Ardennes

Rue Chaumont 5

6980 Laroche en Ardenne

Telephone: International +32 (0)84 411.725

Suggested Reading:

MacDonald: Chapters 6,12,13,24 and 25.

Cole: Chapters 8, 13, 14,19 and 21.

Burgette: ‘Seven Roads to Hell’.

General Der Panzertruppen, Heinrich von Lüttwitz Commanding General 47th Panzerkorps whose Corps surrounded Bastogne and demanded the defenders’ surrender. (Author’s collection, courtesy General von Lüttwitz).