A speech is a solemn responsibility. The man who makes a bad thirty-minute speech to 200 people only wastes half an hour of his own time. But he wastes 100 hours of the audience’s time —more than four days—which should be a hanging offense.

Jenkin Lloyd Jones

In this chapter I’m going to look at how you can choose a logical structure to help your listeners follow your talk, how you can develop key ideas and add supporting material, as well as illustrations and examples. This chapter will show you how to construct a persuasive and entertaining talk or presentation.

Listeners find it difficult to concentrate on the spoken word, so you must give them a framework. This is the equivalent of a contents page in a book or chapter headings and subheadings of paragraphs. If you announce your structure early on in your talk, your listeners will be able to refer back to it if they wander down Route 350 from time to time. By summarizing after each of your points, you can lead them back on the main track with you. Remember, they can’t reread your previous paragraph, so you need to help them when their concentration fails. Your structure must be logical, simple to follow and relevant to your audience. Below I have listed some types of structure which you can use.

Problem/Solution This is a common structure, often used in business presentations, in which an examination of the

problem is followed by a proposed solution. If you are suffering a high turnover of staff, you could describe the problem and show how to resolve it by proposing a more selective recruiting program. If your company has a low profile in the trade press, you could oudine the current situation and suggest a public relations campaign to improve its image. A variation on this structure can be used when you are in a competitive situation — describe the problem, examine a number of possible solutions, pointing out the weaknesses of each, and finally present your own solution emphasizing all the advantages.

Chronological structure In this method the key points are given in a natural time-sequence order. For instance, you could state the origins of the problem and how it developed over the course of a number of years. This is useful if you want to set it in an historical context. It is also helpful when you are instructing or training, as you can demonstrate the sequence of steps or stages in a particular process. Audiences find it easy to follow a logical time pattern, with ideas and facts presented in chronological order. However, it doesn’t allow you to indicate their importance in relation to one another. Your second and fourth points may be more important than the points which precede them, but this won’t be apparent from the order in which you present them. You can overcome this disadvantage in your final conclusion by emphasizing the areas which you feel are most significant.

Topical structure Also known as the qualitative structure, you list your points in their order of significance, with the most important at the beginning. This is useful when you think your audience may not concentrate through your entire talk and are likely to pay more attention in the first few minutes. Generally, the listener’s attention is keenest at the beginning of a talk, and it’s prudent to take advantage of this. Remember that, in selecting your most telling or vital idea, you must refer back to your objective.

Spatial structure In this structure you can either begin with the particular and move to the general or, alternatively, examine the big picture first and then show how it applies to the audience. For example, you may want to analyze the sales

pattern for the past six months and then put it into the context of the previous three years. \ou could present new taxation legislation in broad terms and then explain how it would apply in two particular situations.

Theory/Practice In this structure you outline the theory and then show how it works in practice. It’s often beneficial to link die theory to what the audience already knows about the subject and then progress on to the less familiar. I saw a trainer instructing a young group of new employees in basic telephone manners. He asked them to recall situations when they had been treated well on the telephone and also occasions when they had had to wait unnecessarily. He checked what impression they had of the companies with which they had been dealing. From their personal experience he was able to demonstrate the importance of dealing efficiently with the public on the telephone. He went on to show them the techniques they should use in the future on the telephone, in order to create a positive company image.

I have suggested that you choose a suitable structure at this stage in your preparation, because it enables you to place your ideas in the correct order. If you are undecided on your structure, try writing out your main points on several small cards so that you can change them about easily and experiment with a variety of different sequences.

The next preparation step will depend on the type of talk you are giving. If you are merely speaking for a few minutes at an internal meeting, you may find that you only need to note down a few selected points from your ideas map, choose the sequence which will be most logical for your audience, and your preparation will be complete.

Alternatively, if you are addressing a conference of several hundred people, or bidding for a vital contract, you will want to plan in more detail how you can develop and support your main points and present them in the most positive way.

Think around your key ideas. If your colleagues have some experience of the topic, talk to them, as an exchange of views can often stimulate a new train of thought. Write down any of the examples or illustrations which will help you to emphasize a particular point.

Occasionally when I am preparing a talk, I use a tape recorder at this stage. Imagine that one member of your audience is seated in front of you and you have the opportunity of speaking to him or her on a one-to-one basis. Switch on your tape recorder and talk around your key points. At first you will feel inhibited, but persevere, as you may find that talking aloud opens up previously untapped areas of material and releases ideas which you had stored at the back of your mind. Remember that the purpose of this exercise is to expand the key ideas which you have already selected; you should be researching ways of presenting these main points so that your audience is totally involved and persuaded by you. Try to avoid adding new main points at this juncture. A rough guide is one point per five minutes with a maximum of five points in thirty minutes. You should avoid speaking for more than twenty minutes, but if this isn’t possible, consider using two or three speakers to add variety.

Each of your key ideas is a mini speech and needs to be introduced, developed and concluded; they should be linked together and should have two or three minor points to support them. If you want to write out your talk, some of the suggestions in the following chapter on Writing a Talk may help you. Alternatively, you can write out your main points on white cards (see confidence cards in Chapter 5, Delivery Methods and Systems).

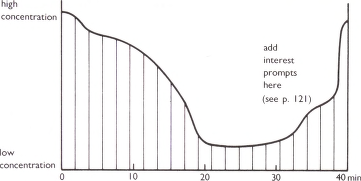

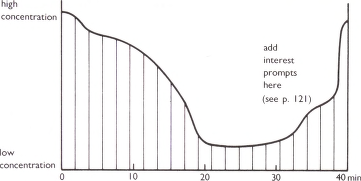

Once you have written or outlined the body of your talk, try to identify where the dull patches occur; you are unlikely to maintain a high level of concentration from your listeners throughout your talk and therefore you need to add color and sweeteners to stimulate their interest. The graph opposite demonstrates this.

Concentration curve of audiences

Aim for a variety of facts, personal illustrations, examples and explanations. It’s this mixture which holds an audience’s attention. Some of your material may be heavy and difficult to digest, so intersperse it with some lightweight examples to make it more acceptable to your audience. Try to break up chunks of essential but dry information with illustrations which are relevant to your listeners. Ask yourself whether some of your points could be better explained with the use of a visual aid. Remember that a visual aid should be a visual expression of an idea which you have used words to describe. It should not be a repetition of the words which you have spoken. Ask yourself whether your audience would find it easier to follow your talk if they had a handout or a chart or a table of figures to refer to.

Is there a natural break between two points where it would be worthwhile asking the audience some questions? Are there any other audience-involving techniques which you could use to break up the presentation? Even changing your physical position helps the audience to maintain their attention. Too much movement is distracting but an occasional change of position from one side of the room or platform to the other enables the audience to refocus.

You only need to consider these suggestions for varying the mixture within your talk if you are speaking for over five

minutes. Under this time the content should be sufficient to keep your listeners alert.

The illustration of the ideas map on page 20 shows how one manager brainstormed the problem of a constant turnover of staff which his company faced. On the ideas map Jim Bains jotted down all aspects of the problem, together with his ideas for solving it. He wanted to convince his board of directors that the company needed to employ a trained personnel officer, but he knew that they considered this an unnecessary expense for a company of their size.

Jim decided that a problem/solution structure most suited his ten-minute presentation, but he also wanted to use some of the other structures to develop his key points. He felt that as the overriding objection to employing a personnel officer was financial, he needed to show how much the continual recruitment of staff had cost die company in the past.

• Jim’s objective: To convince the board of directors that die company could save time and money and create a happier and more productive workforce by appointing a personnel officer.

• How did he achieve this objective? By demonstrating the real cost of recruiting staff under the present system.

• What action did he want which would indicate that he had achieved his objective? Agreement for him to place an advertisement for a personnel officer.

Below is die outline for his talk showing how he developed each of his key points:

1 The problem

(i) How it developed (chronological structure , past-present)

Small tamily run company with loyal staff; sudden rapid growth; inadequate job descriptions; poorly recruited new staff; insufficient training; dissatisfaction and low morale among employees.

(ii) Cost in time and money of recruiting (spatial structure)

Cost ol advertisements; secretary’s time handling responses to advertisement; manager’s time interviewing candidates; nonproductive time for training.

Use flip chart to show true costs of recruiting one secretary. In one year thirty junior staff replaced, e.g. mail-room clerk changed five times. Show total cost over a twelve-month period of recruiting thirty people.

(iii) Why don’t staff stay longer? (topical structure)

Poor recruitment because managers not trained as interviewers; unclear lines of authority 7 , e.g., warehouse packing clerk should help mail room on busy days, but who decides? poor job descriptions, e.g., relief work on switchboard done as a favor and causes resentment; no formal wages structure, e.g., pay increases apparently given at the whim of manager resulting in complaints of favoritism; staff with the company for three years accused of not welcoming newcomers; senior staff don’t know names of junior staff.

2 Solution

(iv) Personnel Officer (chronological present—future) Show main advantages to solving the current problem; overcome any objections regarding costs, i.e., refer to the high cost of recruiting new staff. Other advantages: some departments will be more productive as some aspects of their present work will be handled by personnel officer, e.g., Accounts Department and the payroll, secretaries will not be involved in recruiting; central pay structure — fewer complaints; proper job descriptions — less friction; recruiting with career development in mind, e.g., Customer Service Department currently handles telephoned complaints, with sales training, they could develop telephone selling skills; long-term planning and expansion easier without present difficulties.

You can see from the above example how Jim selected some of the key ideas and developed them to achieve his objective.

He chose to use the flip chart to demonstrate the actual cost

of recruiting one secretary, as spoken numbers are difficult to comprehend and retain. If a flip chart hadn’t been available, he could have prepared a handout showing a breakdown of his calculations to help his audience follow his arguments.

In order that his presentation should not become too theoretical, he gave several examples and illustrations to make it come alive for his listeners, e.g., mail-room clerk, etc.

Although all the ideas on his ideas map were valid and interesting, you will see that because he wanted to speak only for ten minutes he had to reject some of them, but he made sure that the file which he took to the meeting contained the additional information in case he was asked questions about it.

Later on in this chapter you will see how Jim chose to begin and conclude his presentation.

How to start

You may have forgotten that this was the title of the first section on Preparation and Planning. I hope you can see why you need to spend sufficient time and effort on the body of your talk before you reach the stage where you can choose the opening sentences of your talk.

What should your opening words say?

In some ways your opening words are your most important. Although people only half-listen to the content, it’s at this stage that the> are assessing how much of their mental energy you deserve. You will already have made a first impression before you actually say one word, and as they hear your voice (maybe for the first time) you will be failing or passing the next test. How interesting are you? Are you worth listening to? Do you have enthusiasm, sincerity and vitality?

Your first few words must create a stillness as the audience prick up their ears and wait for your next sentence. You must grab their attention and suspend their questioning. Your opening words must be imaginative, stimulating and above all attention gaining. Don’t confuse, your opening words with your introduction to your subject. That comes later. If you feel that

this sounds too theatrical for your business presentation, don’t dismiss the concept completely; look at the examples below and consider whether you could use one or several of them to make your next talk more entertaining.

\ our opening words to your audience must be enticing, seductive and should make diem want to listen to you. You need to capture their attention, stop their minds wandering and show them you’re worth listening to. A tall order, but essential if you expect to achieve your objectives.

It’s as simple as A, B, C and D:

Attention — capture their attention Benefits — show them what they will gain from listening Credentials — give them your credentials for speaking Direction and destination — tell them your structure

This may seem a lot to fit into one paragraph but it can be covered in less than a minute. I have described below these four ingredients in more detail, because from my own experience I know that your opening few sentences can be crucial to the success of your talk.

1 How to capture their attention Ask a question

“Do you know how many phone calls the accounts department receives every day?”

“Can you remember what you were doing on Tuesday, August 11 last year?”

“Have you any idea how many hours you spend in your car each week?”

As you read through those questions, you may have quickly thought of your own answers, and that is what the audience does, or else they listen for an answer from the speaker. Questions engage the minds of the audience and make them concentrate. Don't make your opening question too involved, or they will be working out the answer and won’t be listening to your next sentence; do make the question relevant to the audience.

Quotation

“The brain is a wonderful organ — it begins working the moment you are born and goes on working perfecdy until the moment that you have to stand up and speak in public.”

“There are two kinds of men who never amount to much; those who cannot do what they are told and those who can do nothing else.”

“Doing business without advertising is like winking in the dark —you know what you are doing but no one else does.”

Bookshops and libraries are full of books of quotations and you’ll find you can spend hours looking for an appropriate opening for your talk. I usually hear pithy and amusing quotations from other speakers so I keep a file of anecdotes and quotes which I can refer to when I get stuck. Many of the modern dictionaries of quotations are compiled by subject, which reduces your research time. Some quotes benefit from your giving their author, and you can preface your remark with, “I like the advice that Mark Twain gave on public speaking —‘The right word may be effective, but no word can ever be as effective as a mighty, timed pause.’”

Anecdotes

A short story which launches you quickly into the subject matter of your talk is useful, provided it is relevant to the audience and to your topic. Here is an extract from a story I heard at a meeting of personnel managers in which the speaker introduced his talk by describing the impossibly high expectations of some of the applicants for a recendy advertised job. “One young man said that he liked the sound of the job but that at his last employment he was paid more and the conditions were better. I asked him what they were and he told me that he was given free life insurance, and was enrolled in a private health scheme and that every year there was a 10 percent bonus at Christmas, six weeks paid vacation a year, free travel and every' Friday they finished at 3.00 p.m. I said to him, ‘It sounds perfect, why on earth did you leave?' He looked at me sheepishly and said ‘They went bust’.”

On another occasion I heard a speaker open his talk on business acumen with this due story. “Once upon a time there were two soft drinks companies. One got into deep financial trouble and the other was offered the opportunity to buy them out. The successful company figured die unsuccessful one couldn’t last long and turned down the takeover opportunity. The successful company was Coca-Cola and the other one was Pepsi. Somewhere someone must be kicking himself.”

If you are using secondhand material, try to personalize it so that it appears to be your own experience. But it is generally better to use your own stories, provided you cut out any irrelevant detail. In the chapter on humor, you’ll see that the most successful anecdotes are those which you tell on yourself.