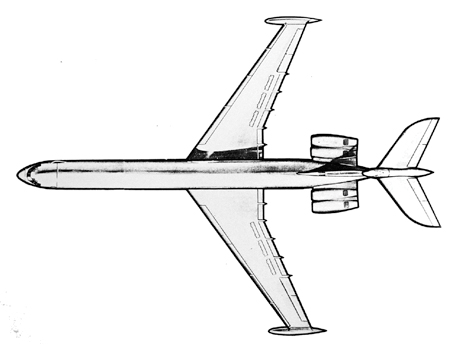

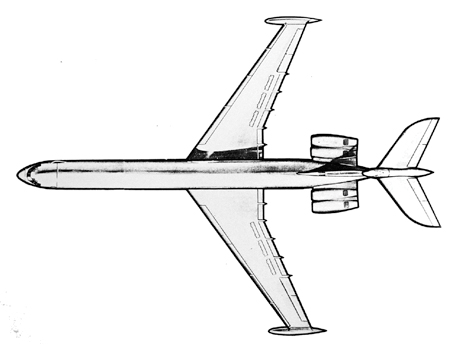

SVC10 LR with Extra Tanks.

In 1963, whatever the fanfares and flag waving of Britain’s ‘golden era’ of aviation, BOAC was in deep trouble, and the taxpayer and their elected representatives were beginning to ask why. Parliament would soon lose patience. Furthermore, the airliners of the claimed era of British brilliance had been somewhat less than that: Only the Viscount had been truly brilliant on a global stage, selling by the hundreds, but Comet had failed and the elegant Britannia seemed to have created a managerial delusion that props, even if turbine-driven, could compete with transatlantic jets. In the late 1950s, BOAC was still relying on a fleet of reconditioned DC-7Cs that simply devoured engines and maintenance costs. Then came nearly £50 million worth of 707 orders.

Initially, in late 1957, BOAC, under the ‘air’ experience of Sir Gerard d’Erlanger, had enthused about the VC10 and dreams of an all VC10 BOAC fleet were not so far-fetched. By 1958 a £77million contract for thirty-five VC10s, plus twenty options, was reality. But BOAC was soon under new management and an all 707 fleet seemed far more likely. BOAC then vacillated and manoeuvred and it was against this backdrop, and of BOAC’s ever-changing orders for the VC10 and Super VC10, that changes took place. The VC10 grew in size and then the real Super VC10 proposal was cut down in scale by BOAC.

Vickers also had cost issues with its original quotes as the VC10 was proving expensive to design and make.

By December 1963, the House of Commons held a debate as ‘Order for Second Reading of the Air Corporations Bill’ – which was a Parliamentary-led look at the financing and management of British airline corporations in the form of BEA(C) and BOAC itself. This would run on into 1964. Julian Amery as Minister of Aviation, who had replaced Peter Thorneycroft, but himself was soon to be ousted by the general election result, had been taking a close look at BOAC; some feared he might try and get a new man (Giles Guthrie) to do to BOAC what Dr Beeching was to do to British Railways! BOAC at that time was the second largest long-haul airline in the world and haemorrhaging money like jet fuel spewing from a leaking wing tank.

A ‘White Paper’ on BOAC was to reaffirm that BOAC’s obligations were to operate as a commercial concern and that if, or where, any need to operate otherwise than commercially arose – on UK Government instructions, or in response to its advice – that this should be done only with the agreement, or at the instance of the minister, for the government.

Of vital relevance, their existed at this time, the separate ‘Corbett Report’ into the running of BOAC, which took over ten months to compile and which was estimated by Flight magazine to have cost about £40,000 to procure. The Corbett Report observed that during the period 1956–1960 there existed the ‘utterly absurd’ situation of BOAC having a part-time chairman with a full-time deputychairman and a board, the large majority of whose members were once-a-month members/attendees.1

Corbett was critical of BOAC’s management – in mechanism and structure – which was roundly criticised, and this ultimately led to more musical chairs at BOAC, but it was all done quietly and oh-so politely, with lots of behind-thescenes niceties to avoid any upset or bad publicity that might annoy the lower orders – the tax payers who funded the affair. Corbett’s main attack was made via a very grave charge against BOAC’s management, one of weakness over financial control, yet the Corbett Report had neither been given to BOAC, nor acted upon by the government. So the Corbett Report had not been shown to BOAC’s Board or other major parties involved – it was being kept away from the headlines. BOAC meanwhile, had, in 1963 alone, racked up a massive £12 million loss. Yet revenue was on the up and over £50million had been handled as transactions. BOAC’s load factor in 1963 was 54% – up from below 50%. A beleaguered Sir Matthew Slattery was still running BOAC and its newish fleet of 707s alongside the fast-paced but weak payload capacity of the Comet 4s. With the imminent VC10, BOAC would, by mid-1964, be operating a long-haul fleet of three differing jet types with three sets of costs to service similar routes (the likes of key competitors like KLM, Lufthansa and Qantas, each had just one jet type for their respective long-haul fleets). Slattery, amid BOAC’s inherited operational burdens, was caught between a rock and a hard place and most parliamentary observers were kind to him (though not all) as he tried to steer BOAC through a mess that was in some sizeable part, of its own creation under his and his predecessors tenures.

BOAC had been subject to the 1949 Air Corporations Act, which empowered the state, via its minister, to give directions as to the form of the corporation’s accounts. BOAC’s accounts showed a deficit of £80 million at the end of March 1963, and a total figure of £85 million was likely to accrue. The Air Corporations Bill now asked for an increase of a £100 million deficit on revenue account – to £125 million. This increase was to provide for continuing losses before BOAC could overcome the problems which it faced. The sums were, by 1960s rates, significant to the national exchequer.2

Between 1956 and 1962, BOAC introduced five different types of aircraft into service and the cost was staggering – nearly £13 million. BOAC had backed the Britannia in both its versions hoping that it would be delivered in 1954 to 1956, but delays occurred leaving BOAC with a real problem – one that the VC7 could have solved quickly! BOAC’s subsequent orders for the 707 seem even more odd when one considers that BOAC’s main, money-earning, premier routes were the services to Africa and Asia. Heathrow to New York might have been important, but it was Heathrow to Johannesburg, and Heathrow to Hong Kong via India, that were BOAC’s absolutely vital revenue streams. So why order an airliner (the 707) that was not designed to operate effectively on such routes and would take years to be developed into an airframe that could adequately service them once runways had been improved. Only then to have demanded a shot-runway ‘hot-rod’ as in the VC10!

Once again, BOAC’s deliberate actions and contradictions over the VC7 look very strange (if not suspect) indeed and its 707 preference appeared utterly contradictory.

As 1963 turned into 1964, Sir Matthew Slattery and Sir Basil Smallpiece had gone from BOAC. Other board members, most of them titled men, were soon to depart. In their place came a banker – a man of trade and of fiscal experience – named Giles Guthrie, who was soon appointed to place a firmer hand upon BOAC. The BOAC ‘club’ had been shaken and stirred. Introduction into revenue service of the VC10 was just a few short months away, so too was a change of British Government – likely to reveal more chaos and bargaining over BOAC. The then unasked question was, would BOAC have enough aircraft when the economic and passenger bookings upturn came – which it surely would and did after 1966?

Total VC10 Cancellation? The Guthrie Plan Gains Pace

To illustrate how close the whole VC10 and Super VC10 project came to being cancelled, we know that the British Government and MPs in the House of Commons had openly discussed the costs of compensating Vickers/BAC if the VC10, and more specifically the yet to be born Super VC10 fleet, were to be effectively annihilated by official move. Total cancellation of the entire BOAC VC10/Super VC10 fleet was actually mooted under Guthrie. The fact that Edwards and Vickers had got on with building the VC10 fleet at a very fast rate, meant that by 1964 over half the VC10 fleet had been constructed – real airframes that could not be ‘disappeared’ without compensating the manufacturer. But the Super VC10 was still in its early build.

MPs on the political Left leapt on the bandwagon and accused the government of not just vacillation, but chaotic management and strategy. The incoming Guthrie may have got close to stopping the Super VC10 in its tracks. What had been an order for thirty-five VC10s had been drastically shrunken, yet with more Super VC10s ordered, but not enough to compensate for the lost Standard model VC10 orders. That order too was curtailed. What had started off as forty-five VC10 orders, had ended up as fifteen VC10s and thirty Super VC10s, only then to be cut down to ten VC10s and thirty Super VC10s. Then came Guthrie and the cancellation of half that Super VC10 order; then all of it. The on-off nature of BOAC’s VC10 and Super VC10 orders endured through into Guthrie’s final ‘chop’ to the Super VC10 orders – only seventeen to be built, alongside the twelve Standard VC10s.

An all-Boeing BOAC was at one time a real possibility, but of course, the political fallout over Westminster and Wisely would have been massive. Guthrie may have thought he had the authority to get away with it. Prior to all these shenanigans, the British aviation industry was in the wake of the post-Sandys Report era of mergers, and the creation of the British Aircraft Corporation as BAC after 1960, just as the VC10 was being defined and laid down. Airliners, their design and their orders from the state carriers – BEA’s Trident to de Havilland’s as part of Hawker Siddeley, and BOAC’s VC10 to Vickers, cannot have been irrelevant to decisions taken circa 1959–1961 over BAC.

On 22 November 1963, The Financial Times pointed out that if it was the intention that Sir Giles Guthrie should produce a ‘Beeching’ type plan for BOAC, that this surely would meet with opposition from the Foreign Office, the Defence Ministry, and all those ministries which had an interest in the activities of BOAC – not just as an airline, but, it seems, once again as a national ‘instrument’. And as the newspapers said, it would not be possible to estimate such effects, in a simple, profit-and-loss account.

Back in Parliament, the reality of BOAC wanting to spend the astounding sum of $2million (a huge amount in those days) in 1964 on a VC10 advertising campaign saw the comment made in the House during the second reading of the Air Corporations Bill that, ‘a two million press advertising campaign has just been launched about the wonders of the VC10, which was constructed to the specification of BOAC and which will be a very fine aircraft.’3

In the same debate, Minister Amery told the House of Commons:

‘The reason why there is no detailed reference to the VC10 in the White Paper is that no part of the deficit has resulted from the VC10 because it has not yet been introduced into service. It would be quite wrong to accept easily the idea that the VC10 was something pushed down the throat of the corporation. It was not. I think that experience will show that this remarkable aircraft, the quietest aircraft in which I have ever flown, will prove a very great commercial success in a short time from now.’4

So the Minister was clear, contrary to BOAC’s bleatings, the VC10 had not been forced upon BOAC (which had surely been a willing partner), and that prior to BOAC’s complaints about the cost of operating the VC10s for which it had asked for and influenced so heavily, BOAC was losing a massive amount of money from its operations – which included having the Boeing 707 and the darling of the Empire, de Havilland Comet 4, in its fleet.

The VC10 was, during 1963–1964, plastered all over the national aviation media and the debate. G-ARTA and the early BOAC machines were real – flying in testing. The Super VC10s were being laid down. Surely the VC10 project could not be subjected to a V1000-style last minute termination as yet another ‘project cancelled’?

So was set the VC10 prior to, and during its launch era. Then, in 1964, just as the VC10 took flight, came more movement of boardroom chairs at BOAC and more political change in Great Britain’s elected government. The ever-changing game of political musical chairs and all its implications upon policy for BOAC continued its sorry course.

But by then there was Guthrie, Sir Giles Guthrie; and the VC10 story took yet another turn. What had been a bit of turbulence, was about to become a hurricane of swirling opinions. Guthrie would openly criticise the VC10’s operating economics alongside the cancelled pre-existing Super VC10 order book; order numbers were subjected to the changes – harming the VC10s image before the eyes of world. And as Sir George Edwards opined, if your own national airline was unwilling to buy your product, what did that do for the machine’s sales hopes with overseas airlines.5

BOAC’s prior incumbent, Sir Matthew Slattery, had reputedly wanted to cancel the VC10 fleet in its entirety and create a big BOAC squadron of Boeings, and yet he had to accept the political diktat to support the securing of a British, four-engined, transatlantic airliner of a capacity far bigger than the one BOAC already had to hand in the form of the Comet 4. Slattery was only doing his job in trying to protect BOAC’s deeply worrying financial position, but such ignored the other factors that were part of the BOAC story and national function and BOAC’s previous commitments to the VC10. Here again was the conflict over what was BOAC’s actual role? And where was the money coming from? The fact that BOAC had spent nearly £50 million on its 707 orders and the effects thereof seemed to have been conveniently forgotten by BOAC. As Vickers were creating the VC10, the Amery-plan emerged, and then came Guthrie as yet another man in the hot seat at BOAC tasked with trying to do, or be, more than just one thing – an airline! Then the British Government changed again and Labour, as opposed to Conservative politicians, had their chance to kick the VC10, or support it.

Labour’s Roy Jenkins had already kicked the VC10 with his views of ignorant certainty, but the 1963 Minister for Aviation had been the Conservative Julian Amery, and he was clear, BOAC needed a plan to run for profit and he said the VC10 was a great thing. But soon after, the Left and Harold Wilson were in power. The Labour politician and MP John Stonehouse had opinions about British ‘air’ policy and he too was astounded by BOAC’s conduct and attitudes – he became Minister for Aviation and thought the BOAC Board had been of a blinkered and self-serving outlook. BOAC had just cancelled a major tranche of its Super VC10 order and worse was to come. Stonehouse supported the VC10 and its marketing, calling it a ‘marvellous’ aircraft, yet would always run up against the might and impact of BOAC’s and Guthrie’s view of the aircraft – which by this time was public knowledge, much to the Americans unalloyed joy. Hidden was the fact that BOAC’s VC10 fleet had begun to make money, and by late 1967 the Super VC10 fleet was creating a profit! Stonehouse tried, and failed, to sell VC10s to Middle East Airlines. Edwards had a high opinion of Stonehouse – which helped.6

Whatever Stonehouse’s emotions and support of the VC10 and its workers,7 Giles Guthrie had been empowered to run BOAC as an airline business, not a Civil Service instrument of some historical or national fantasy of influence and flag-waving. Apparently, BOAC could now have the freedom to choose what type of airliners it could purchase. Did this give the ex-banker Sir Giles Guthrie, as BOAC’s new man, utter freedom to buy and operate whatever airframe he wanted? Of course, by this time, the VC10 was into service and the Super VC10 ready.

Giles Guthrie has received much criticism for his own critical position over the VC10, and yet fairness requires that we respect his job title and the parameters he was instructed to follow, even if they, government and the ruling party, had all changed. But Guthrie’s authority and orders were new, revised parameters, new rules for a new BOAC that contradicted existing and cast rules, functions and actual existing VC10 orders – where jobs were at stake – as might be Vickers itself. To usurp pre-existing strategies at vast cost was a position that might be logically argued for by Guthrie, but by then, government and BOAC had long-created a seemingly strategic irrationality that was up and running as an operating policy. After all, the VC10 had been asked for by BOAC and was flying, via Vickers genius, as requested by BOAC; by 1964 and VC10’s entry into service, many proverbial chickens had started to come home to roost, and at Brooklands a brood of new VC10s were awaiting their first flight. There they sat, all liveried up in dark blue and white tail stripes with ‘Speedbird’ emblems and gold coach lines. They would soon be repainted in the new, defining BOAC blue and gold livery with its emotive golden ‘Speedbird’ on that stunning tail fin, a sight that would become so very evocative and so very famous.

To many VC10 enthusiasts, Guthrie was the villain of the Vickers story: although not absolving him from his actions, we should perhaps see a wider BOAC and British picture before ‘blaming’ just one man, no matter how much we disagree with what he said! There is no doubt that Vickers, and the industry’s relations with BOAC were soured by the airline’s actions, and Edwards and Trubshaw were both less than polite about what went on.

There have been many rumours about BOAC’s Board members, or influential others, having suggested alleged links and interests to, or in Boeing, but such claims, be they true or untrue, miss the point. It was government, successive governments, and BOAC Boards, that created the mess of which BOAC was party by design, not just by choice. BOAC seems to retrospectively have decided that it was ‘forced’ into the VC10, and then, having specified the VC10, decided that the VC10 was too expensive to operate. BOAC certainly did cancel a vast tranche of Super VC10s, but to simply blame Guthrie alone is to miss the point and the consequences of the Imperial and BOAC story to that date.

At least by 1965, BOAC had decided on going down the jet only route, but of significance, BOAC had by this time, decided to divest itself of its still young fleet of elegant and adored Comet 4s. The low-capacity, fuel-hungry Comet 4s were got rid of in very short time indeed and the reason was based on costs and capacity issues. As always, Comet 4, born of Comet 1, was too small, and Guthrie put aside national pride and ego and got rid of them p.d.q., with little emotion allowed.

Around the VC10 and BOAC, a degree of legend or myth has been created in opposing arenas. Surely we can observe that creating the VC10 was a very difficult task that would have defeated many men. But Vickers did not just deliver, they delivered something special. It might be rationally argued that by the early 1960s, BOAC had had its fill of British airliners being delayed in design and late into service, and the costs that BOAC had had to carry in dealing with such issues (securing interim aircraft and crews). But why should Vickers be tarred with that brush? Such design issues as seen in Comet and Britannia, were not Vickers’s fault (nor BOAC’s), but the overall and unique British airline circumstances surrounding fleet equipment procurement as not just, prop-versus-jet, but also in terms of size and capacity, allied to funding, operating and management issues, had been contributed too and co-created by BOAC. The airline’s own identity, history and corporate culture encompassing all the issues previously discussed herein as historical, political, and societal issues of Imperial Airways and imperial Britain.

Guthrie’s era revealed that BOAC could openly criticise the VC10’s operating economics. BOAC demanded and got a subsidy for having to operate what it said were fuel-thirsty VC10s – a reputed £30 million. Yet those aircraft soon made a profit and BOAC was then very cagey about revealing its Super VC10 operating economics, and as we know from figures cited herein, the difference between Super VC10 operating costs and 707 operating costs by 1969, was minimal, and the Super VC10 fleet flew for more hours per day and required less cost in repairs and ground time and enjoyed a long-lasting load factor enhancing appeal advantage. Yet Guthrie publicly criticised the VC10, and in doing so, the VC10 and Super VC10 were damned in the eyes of the airline world and export market. The damage was probably incalculable. Yet no technical deficiency in the design or airframe was ever cited or evidenced. The nuances were more multi-layered. The likes of John Stonehouse and Tony Benn could do little to correct the Guthrie effect upon potential customers – it was all too late – the alleged misinformation had got out; yet it ignored the wider VC10 and Super VC10 benefits of passenger appeal, fuller load factor, slower, safer, take-offs and landings (also cheaper on tyres and brakes), and of real note, lower maintenance and repair costs.

Despite all its negatives, BOAC (even under Guthrie) threw a very large amount of money (£2 million) and reputational profile at promoting the VC10, and especially the Super VC10, creating a unique and innovative advertising and marketing legend.

The paradoxes of BOAC were obvious then and now.

1964: VC10’s Service Begins

Hyperbole is easy, but persuading people of a truth is harder. Pilots were truly amazed at the flying qualities of the VC10 and its larger and heavier brother the Super VC10. Over-winged, over-powered and for accounting bean counters, over-designed, the VC10 offered reserves of handling and performance that were outside the experience of most civil aircrew at the time – or since.

Converting to a VC10 from a Comet was one thing, converting from a propeller powered device like a Britannia or a DC-7 was far more of a shock. Yet even jet experienced Comet pilots were amazed by the VC10’s take-off performance, of the very slow take-off and landing speeds – at least 20kts slower than its rivals – followed by what must have felt like a near-vertical climb.

The few 707 pilots who flew the VC10 were simply staggered at the differences.

The VC10 pilots all agreed, saying things that reflected their genuine love of flying an airliner that handled, said some, like a jet fighter.

‘Truly superb’: ‘Incredible to fly’: ‘Huge performance and safety reserves’: ‘You knew it would not bite you, and that it could also get you out of a nasty situation.’

‘Simply the best handling and best performing four-engined jet this side of Concorde.’

‘Wonderful, handled like a sports car, but built like a tank. Simply brilliant to fly’: ‘I transferred from VC10 to Concorde and felt well prepared.’

‘VC10. It was utterly viceless. Engine out was easy.’: ‘Much easier to fly than a 707, especially if you lost an engine, and even more so if that occurred shortly after take-off.’: ‘Felt like it was carved from solid.’: ‘Stable in turbulence and so reassuring.’8

Such were the comments of VC10 pilots – even Comet 4 pilots coming over to the new BOAC machine were taken aback at the ability and ease of the VC10.

At East African Airways, there were new VC10 pilots converting from Comet 4s, but also from DC-3s and Argonauts! Imagine the test of transferring from nosedown, prop-powered approaches, and changing from 5º or 10º take-off angles, to learning about how to fly four Rolls-Royce Conways and a high-lift VC10 wing – a machine that could go upwards at nearly 20º in normal use!

BOAC VC10 Captain Terence Brand recalled that: ‘The VC10 was a lovely aircraft. It handled like a dream, being smooth and progressive. All that power gave you confidence and great safety reserves to get out of trouble. The landings were very flattering, and only in crosswinds was some caution required. The sound of the Conways on take-off was like tearing of calico, and the push of thrust, unique.’

One of BOAC’s lead VC10/Super VC10 training commanders was the exwartime RAF bomber pilot, Tom Stoney. He said of the VC10: ‘It was really terribly easy to fly. Only that narrow undercart needed watching in crosswinds. The VC10 was so safe, and almost flew itself down the ideal glide path to arrive at such a slow speed compared to the Boeing.’

Captain Ronald Ballantine recalled that the VC10: ‘Flew like a dream, a fightertype performance. Stable, safe, and with far less deep stall worries than other types. BOAC crews were rightly proud to fly it, and of course, we never lost one.’

Captain James L. Heron was a member of the VC10 development crew and coauthored the BOAC VC10 flying manual, yet his name is rarely cited in the VC10 literature. An Australian, he had flown the Consolidated Liberator for the RAF, Lockheed Constellations and Bristol Britannias for BOAC before transferring to the VC10 fleet. He was also on board the Super VC10 inaugural flight LHR-JFK on 1 April 1965, captained by Harry R. Nicholls. James Heron retired in 1971 with a BOAC seniority number of Three. Captain’s Heron’s son once asked his father which aircraft, of all the numerous types he had flown in a career which spanned forty-four years, was his favourite? James Heron answered without hesitation: ‘The VC10. It truly was superb.’9

VC10 fleet captain, Norman Todd, loved the aircraft, he went on to fly Concorde and opined that the VC10 was not just utterly brilliant, but a good training ground for Concorde pilots.

VC10 and Concorde test-pilot (chief test pilot for BAC), Brian Trubshaw, was categoric: ‘The feel of the VC10 flight controls was superb – artificially created, but utterly realistic and accurate. Despite the weight and the carved from solid structure, she was light to handle. A firm pull on the stick got her off and up very quickly. Then it was that amazing climb angle until you throttled back, the fuel gauges swung down to a better flow rate and once cleaned up, the VC10 and Super VC10 just cleaved along. Losing an engine was no big deal.

‘Only at low speed, high weights, or at very high altitude, were some of the speed/stall margins a bit tight. Like any swept-wing device the VC10 would Dutch roll too, but not in airline service. We did insist on that high inboard wing fence to cure some low speed instability and it dealt with spanwise flow near the stall and helped the engines too. You could place the VC10 down with ease and great accuracy – ideal for short fields. The Super VC10 retained the excellent flying qualities at the deliberate expense of short runway ability.’10

Another well-known VC10 pilot was Norman Tebbit – latterly a leading politician in Britain’s consecutive 1980s Conservative administrations under Margaret Thatcher, but in an earlier life, a BOAC pilot and VC10 admirer.

In 2003, in an Aeroplane magazine poll of pilots opinions as to which aircraft was the best pilots aeroplane under a context of ‘pilot-thrilling’ question (i.e.; in terms of handling, power and abilities), the readership voted not for a jet fighter or even Vulcan or Concorde – but for the VC10.11

A VC10 forte was its ease of control in asymmetric thrust conditions. Losing an engine in the cruise required minimal trim ‘tweaks’. Losing an engine soon after take-off, or on the climb out, demanded far less effort than in an airliner with widely spaced, wing-mounted engines that lay further out from the centre line. A VC10 losing an engine at a critical early flight stage from the runway needed corrective rudder input, but no great drama ensued – those four engines were close to the centre thrust line. A Boeing 707 in the same condition – take-off or goaround – would require large rudder inputs and rudder pedal forces of over 100lbs from the handling pilot(s) to hold the 707 straight. The ensuing minutes of physical effort would test any pilot. Trim and power adjustments and a very reduced climb rate were all to be expected – especially in a heavily loaded 707 – where climb rates would be minimal and rudder induced drag, significant. The additions of a taller tail fin, and a lower ventral fin (ultimately in two sizes!) to the 707 was demanded by the British airworthiness authority prior to certification for British use of the 707 – directly reflecting the directional control issues encountered as certain weight and power configurations: the ventral fin later became production line factory fitments. The VC10 of course had three rudders.

Sometimes, exotic car and aircraft designs that look stunning and have power can be real handfuls to master – they can contain hidden vices to catch the unwary or the complacent commander. Often, with power and performance, there can be a sting in the tail. This was not the case with the VC10 which was vice-less in normal use and offered massive active and passive safety advantages. True, it had the potential to deep-stall as all T-tailers can, but the VC10 never suffered from a deep-stall related crash – due to its superb design and well trained pilots. The spectre of ‘Dutch Roll’ – a blend of twisting and turning in flight – might also afflict its rear-biased swept-wing and CG and polar inertia combinations, but again not in normal airline use. Pilots were trained to ‘catch’ ‘Dutch Roll’ with deftly applied aileron and rudder, and if necessary, a whiff of the spoilers.

For the pilot, the in-service passenger loaded VC10 could be flown off from very short runways in very testing airfield conditions of weight, altitude density and temperature (known as WAT-limited). Having rotated off the runway, the VC10 could then be hauled into a 15º + climb angle and rocketed upwards to achieve safe, positive climb and terrain clearance in a far quicker time than any rival 707 or DC- 8. In the cruise, the controls were easy and responsive; on the landing approach the VC10 could be guided in at 20kts slower than a 707, and could buy its pilot time on the approach – very beneficial in bad weather and poor visibility, and safer onto the short tropical runways. Instead of crossing the runway threshold at 160kts+, as in the case of a heavy 707-300/400 series, a VC10 could be calmly guided down the approach path angle with up to six degrees nose-up attitude held, slats and flaps dangling, power protectively spooled up, and then placed confidently down onto the tarmac at 130kts +/-, which was 20kts or more slower than its 707 rival.

The heavier Super VC10 required a few more knots over the VC10s more usual alighting speed regime and a maximum weight approach speed of 137.5kts was cited – still much slower than the 707 and DC-8 – with all the inherent safety advantages and reduced tyre and brake distress. Very occasionally, lightly loaded VC10s might actually alight on the tarmac at 120kts, which was unheard of in a big four-engined jet (the claimed touchdown speed record is 117kts on a near-empty VC10). Once down, the raked main gear with its cranked main mounting beam, would soak up the touchdown forces; the cushion of ‘ground effect’ air under the main wing and Fowler flaps would further soften the landing – a bit like a Deltawing!

The undercarriage (retracting into the body, not solely into the wings) was, however, narrower than the 707s stiffer-legged, wider-stanced main gear, and the VC10 had to be accurately held wing down into crosswinds – the bigger tail fin keel area also catching the crosswind. However, the much slower approach and landing speed of the VC10 offered significant safety benefits over the 707, DC-8 and notably, the Convair 990.

VC10 tyre and brake temperatures and wear would all be lower, and the risk of a wing scrape reduced.

The VC10 was quite happy to enter the landing holding pattern at under 230kts ‘clean’ – that is without flaps and slats – then deploy those high lift devices for a slower flight profile at circa 190kts. Putting the undercarriage down and offering full flap at 180–160kts was a bit more fuel thirsty, but the VC10 and Super VC10 offered great stability and safety at these speeds, and the ability to perform a very sprightly go-around manoeuvre from close to the runway. The thing to avoid, as with all T-tailed, rear-engined and rear weight-biased jets, was getting low, slow, and with engines spooled down and with up-stick being ‘pulled’ by the pilot – that way led to the high sink rate that could lead to disaster near the ground, as early Boeing 727-100 pilots found when they failed to follow the rule book, resulting in a string of crashes.

Once on the ground, the very low touchdown speed made stopping the VC10 with thrust reverse and brakes, an easy task, only the narrow track undercarriage required watching if a crosswind was running. Holding the relevant wing down into wind was soon learned and, of course, there was no risk of scraping an engine pod on the wing into the ground – a real issue for all, wing-pylon equipped aircraft at even moderate roll 10º angles. VC10 pilots held the into wind wing down, all the way along the runway to under 50kts and were alert for the big tail catching a crosswind and ‘weather cocking’ the machine on its wheels. In a crosswind approach a VC10 liked to be flown ‘crabbed’; that is nose into the wind angle and held on the rudder. Just before touchdown the aircraft was to be straightened up – ‘kicked’ with rudder, and then the into wind wing held down. The alternate crosswind method of cross-controls, one wing held down, and large amounts of opposite rudder, was an option, but it caused higher drag and loads on the tail.

Just like Boeing’s high-tailed T-tailer, the 727, the VC10 needed a special technique if it was subjected to a bounced landing – the power had to be reapplied to regain effective airflow speed or ‘control authority’ over the elevators, so that the aircraft could then be re-pitched. Loss of airspeed meant loss of elevator effect at very low speeds, so a bounced touchdown required decisive action rather than the old technique of avoiding a pilot-induced effect (or oscillation) and letting the aircraft ‘re-land’ itself.

Cabin Comfort & BOAC marketing

The new airliner brought in new standards of cabin services and fittings. Originally designed to have a ‘classical’ blue and gold interior featuring the Speedbird emblem, a late change was made to see softer, more muted tones, and of significance, checked seat coverings for the new Economy Class seat design. For the later Super VC10, a further revised interior palette was created by Charles Butler Associates of New York, led by Mr Alex Howie, with designs by Robin Day, RDI, ARCA, FSIA, were featured in the interior – with BOACs views of what they wanted framed by BOACs VC10/Super VC10 project manager Mr Jack R. Finnimore.

For the interior, BOAC wanted something new and bright for its shiny new airliner, yet paradoxically, the interior needed to be restful for long flights. The design brief was, therefore, difficult. The answer was to create muted cabin walls and carpets, populated by bright colours and patterns for seats and trims. Latterly, BOAC/BA spent money on a Super VC10 interior with slightly psychedelic ‘popart’ designs for the cabin bulkheads and new seat trims, this was put in along with large overhead bins in an interior upgrade for the 1970s. Sadly, for technical reasons, in-flight film screens could not be installed – whereas they could on the 707 fleet.

A VC10 hallmark was the superior quality and comfort of the Economy Class cabin – a new seat design built with a forwards, single spar, with a one-piece moulded construction that could be wiped clean and was light in weight – much lighter than normal seats, yet still safe with a near-15g rating, well over the 9g standard rating and very comfortable due to having ‘proper’ cushioning and lower back support that moulded itself to the occupant (all sadly missing from today’s ultra-thin seats which promise more legroom, but offer less cushion comfort); the better cushioning (using Italian Pirelli neoprene webbing) really did mark a change from existing standard class interiors. The seat had a hiduminium alloyconstructed forward cantilever support beam, another new innovation of the VC10 design that was latterly copied. BOAC spent over £300,000 on its new seat orders to the Aircraft Furnishing Company, and took full page adverts in the UK and overseas media proclaiming the excellence of the standard class seats – even citing the 7ft tall American basketball player Wilt Chamberlain as being a man who could get comfy in a VC10 seat. For the Super VC10, BOAC wheeled out no less a celebrity than the venerable Marlene Dietrich and her legs, to proclaim the comfort of the seats and quietness of the ride.

The VC10’s new (30 ton volume capacity) advanced cabin air conditioning could also cope with extra cabin demands of more passengers in tropical climes.

BOAC’s adverts also stated that the VC10 was a ‘great step backwards in air travel’ due to the rearwards mounted engines and consequent quiet cabin. Another BOAC advert proclaimed that the airline had its ‘nose in the air’ – apparently this was not a reference to British snobbery, but to the VC10s excellence and its takeoff abilities. Early BOAC launch adverts for the VC10 featured an oil painting of the VC10 and a strapline stating that the VC10 was: ‘Triumphantly Swift Silent Serene’. Today we might think such an approach a bit pompous, but then, it was the context of the time, as were shots of pretty blondes looking alluringly into the camera in BOAC VC10 advertisements.

The VC10s interior cabin was at its widest mid-aisle, half-width to side wall radius point, 69.3in wide; Boeing’s 707 was 69.0in and the DC-8s 69.25in. Maximum VC10 internal cabin width was 11ft.6in, external 12ft.4in.

Five toilets (six for Super VC10) were built in, although those at the rear were placed aft of the rear galley – which cabin crews found annoying when they were trying to work due to passengers walking through the galley.

Thanks to clever operational management under men like Ross Stainton, the BOAC cabin service was of the highest quality, as were the food, beverage, and amenities – especially on Super VC10 transatlantic runs. Entering the VC10 was like entering a calm oasis for beleaguered passengers and as the engines were at the rear, most of the cabin was very quiet with none of the vibration and noise associated with the Comet’s underfloor wing root engines, and considerably less noise, vibration and harshness and jet efflux fatigue on the rear cabin walls – particularly in the seats aft of the wing where the VC10 was free of the 707s engine reverberations against the fuselage. Outside and underneath the VC10, those Conway Co12s at full thrust were somewhat noisier.

First Service and the Only Way to Fly

Six years after the VC10 design and build process had begun, on 29 April 1964, the first commercial VC10 service was launched. After months of route testing, BOAC polished up it’s, by now well run-in G-ARVJ ‘Victor Juliet’, and launched it from London Heathrow towards Lagos, Nigeria via Kano. At the helm were top BOAC Comet men who had become the early core of VC10 experienced commanders and senior first officers. The first flight was commanded by Captain A.M. Rendall. G-ARVI ‘Victor India’ followed on down to West Africa on the 30 April. BOAC used stops at Frankfurt or Rome on the Nigeria service, and from such beginnings, VC10s began to replace Comet 4 and Britannia 312 equipment on BOAC’s routes in Africa – notably down to Nairobi on the lucrative Johannesburg service – with a stop at Salisbury en route. Services to (Southern) Rhodesia were terminated under the political crisis and BOAC VC10s used Lusaka, Lilongwe, and then Blantyre as new stops instead of Salisbury. Accra was also served and the old Imperial staging post of Tripoli retained. VC10 services soon tracked eastwards to Beirut, Bahrain, Karachi, Calcutta, and Delhi. Soon Singapore saw VC10s and Hong Kong was VC10 country too.

BOAC deployed its 707-436s as premier services across the Atlantic and also on the Pacific routes, and it would not be until the Super VC10 debut that such routings would switch to the VC10 family. From 1965–1969, BOAC used its Standard model VC10s to build up a Middle East route network to service the growing economies of the region – much money was earned by BOAC. Some VC10 routes from London went to Rome or Zurich, thence to Tel Aviv or Beirut, then onwards to the Gulf States and India. In doing so, Imperial’s operations were being mirrored in the new, post-Comet, second jet age. It would be 1973 before BOAC VC10s opened up Addis Ababa service to Bole Airport, which was 7,625ft above mean sea level and also subject to temperatures in excess of 35º C – true ‘hot and high’ operations. The delay in servicing Addis Ababa was down to the state of the existing runway (an EAA Super VC10 had ‘sunk’ into the tarmac). From Addis Ababa, the BOAC VC10/Super VC10 route scythed down across the Indian Ocean to the Seychelles and Mauritius. Visits to very difficult runways at Entebbe and Ndola were also regularly undertaken by these large jets.12

The BOAC branded ‘Super VC10’ entered service on 1 April 1965 with Captain Norman Todd at the controls on the daily premier Heathrow to New York JFK run. G-ASGD ‘Golf Delta’ opened up the route and soon extended it down to the Caribbean BOAC destinations. Boston, Bermuda and Toronto were all Super VC10 destinations – with service to the US West Coast planned, but at that time, still the preserve of the longer-ranged BOAC 707-436 machines. The 707s were replaced on the runs to Chicago as early as 1966 by the Super VC10. In 1969, BOAC’s existing Far-East 707-operated service was modified; 707s still served Los Angeles and Tokyo, but the Super VC10 was used on a round-the-world routing westwards from London Heathrow to the USA, thence to its western seaboard at Los Angeles, then across the Pacific to Honolulu, Fiji and Sydney. Going the other way, a service via Africa and the Seychelles would range up to Singapore and Hong Kong to link up with BOAC service on an east-bound Pacific route.

Often forgotten were the BOAC VC10/Super VC10 forays into South America – Lima and Caracas being favourites prior to the British Government’s 1974 handing over of BOAC’s South America services to BUA and British Caledonian. BOAC also lost its Nigeria route too. The BOAC VC10 fleet also played a major role in developing long-haul routes from Manchester and Prestwick as those airports grew in importance.

BOAC trained its VC10 and Super VC10 crews at Shannon Ireland and then at Prestwick Scotland. After having gained consistency of excellence under the watchful eye of senior BOAC captains such as, Dexter, Field, Fletcher, Futcher, Gray, Goulbourn, Harkness, Hoyland, Knights, Lovelace, Rendall, Stoney, Walton, and others, the new pilots were sent out onto the new VC10 routes. Of note, BOAC’s senior captain – admired by colleagues as a ‘gentlemen of the old school’ – Cyril Goulbourn, would later be the commander of the Super VC10 hijacked and destroyed at Dawson’s Field on 12 September 1970. Captain James Futcher would command the Super VC10 that was hijacked on 21 November 1974 at Dubai and flown to Tunis prior to the hijackers surrendering (another Super VC10 was to be hijacked on 3 March 1974 and destroyed at Amsterdam Schiphol).

Throughout 1963, Vickers began to deliver the BOAC VC10s, and over 10,000 hours of route and airframe testing flying hours were flown by early examples of the BOAC fleet prior to the aircraft’s 1964 service introduction. Day-return trips to Africa – with minimal jet lag due to only a one or two hour time difference – allowed the crews to work through any snags or operational issues prior to service launch. J.R. Finnimore was BOAC’s top VC10 project and development manager from 1958 onwards and truly understood the machine, its concept, and its application.

BOAC launched the heavy publicity and marketing campaign for the new VC10 (and one year later the Super VC10) with advertisements in the national press and trade publications. TV and cinema adverts set to ‘emotional’ music with trumpet fanfares of Purcellesque nuance were broadcast, as was the new golden Speedbird imagery. BOAC even mentioned the new airliners very slow and safe landing speeds. Much was made of the VC10s power and style, and those new Economy Class seats which were of a new design and cited as the ‘most comfortable’ Economy Class seat in the world (most people agreed). The seat pitch was a generous (by today’s standards) 34/35 inches (45 inches in First Class) and the cabin fittings and furnishings were of the highest quality. Fine food, great cabin service, and much better air-conditioning than used on the Comet, ensured that the new cabin environment and service offering were of exceedingly high quality. The BOAC VC10 cabin comfort and service, be it Economy or First Class, was a defining marketing tool for the airline and the cabin crews were rightly popular for their attempts to ‘take good care of you’ – as BOAC’s publicity spin promised. By 1965, BOAC were offering First Class Super VC10 passengers Dunhill cigarettes, quality brands of food and alcohol, very fine wines and a prestigious First Class service in its serene twelve or sixteen seater cabin on North Atlantic and other runs.

With low noise levels, an air of British reserve, and featuring classical etched murals of London and the Thames, as seen in 1647 by Wenceslaus Holler, depicted on the cabin bulkheads, the BOAC VC10 cabins soon became the preferred way to travel.

Load Factor Facts

After the Super VC10 debuted on the New York run, passengers were wanting a Super VC10 booking only – 2,000 seat bookings were taken in the first eight weeks and 100 passengers a day were choosing the Super VC10 service over the BOAC 707 service. Load factors were up to 90%, rarely below 70%, and they stayed that way for a very long time – just as they did on the original VC10 services to Africa.

It might be argued that load factor as an economic calculus is an unwise component, not least as load factors tend to decline after a new airliner’s novelty value wears off. However, in the case of the VC10, the aircraft’s passenger appeal created a long-lasting load factor related operational component. A tough marketing sales type would surely argue that, who cares how it was achieved, but if an aircraft displayed consistent passenger appeal as a booking preference, then that added value should not be denied to the aircraft type responsible: money is money however it is earned. The truth was that the VC10 and Super VC10 subbrand within BOAC’s overall brand did attract preferential bookings over the other types such as the 707 – for years, not just months of novelty. Within twelve months of the Standard VC10s commercial launch, BOAC were recording a 40% VC10-only booking preference from customers. BOAC upped its cabin service offering to capitalise upon that. The VC10 and Super VC10 were a marketing man’s dream and BOAC should be credited for having made the most of the imagery and quality.

Figures from the International Airline Transport Association (IATA) for April 1965–May 1966, show that the BOAC Super VC10 services, in comparison with a ‘basket’ of fourteen other airlines that operated 707 and DC-8 services, had a load factor advantage of 20–25% on a consistent basis and even a lowest advantage of 10% (November 1965). Such was the stuff of the appeal of the by now ‘Swift and Serene’ BOAC Super VC10. Even after BOAC introduced its first 747-100s on the transatlantic routes, passengers still preferred the ‘gold standard’ Super VC10 service – despite the lack of in-flight visual entertainment. The VC10 and Super VC10 built an enduring passenger appeal that was worth millions to BOAC in seats sold, yet rarely accounted for in accountant’s figures, amortisation formulas, and BOAC criticism of the machine it had requested to its own demands.

VC10 flight crews were a happy band – after all they were not paying for the fuel! However, early over-powered days were soon controlled by a VC10 step-climb procedure to conserve fuel and engine life. Still, faced with a hot day and a loaded VC10 at Entebbe, Ndola, Lusaka, Nairobi, Karachi or somewhere similar in Africa, Asia or South America, the answer was simple: ‘Full power on all four!’ Whereupon the VC10 would leap off the line, blast down the runway and begin to fly in about a 25+ seconds timed take-off run, perhaps having used less than 6,000ft of runway, then clawing nose up as the Rolls-Royces pushed for all they worth as their exhausts went nearly supersonic with over 40 tonnes of thrust pouring out the back.

Out of vital Nairobi, as the main mid-route stopover on BOACs major revenue earning route to South Africa, and as a port for other operators VC10s and Super VC10s (BUA, EAA), it was obvious that underpowered 707s, such as those of BCAL or Lufthansa, were limited in their take-off weights. Some suggest that even the turbofan 707-320B/C had a weight-limited take-off figure of around 125 tonnes – which was a massive 22 tonnes below permissible maximum weight and often requiring off loads of fuel or passenger/freight payload. In comparison, Standard VC10s could manage to take off at about 142 tonnes, which was only ½ tonne below maximum allowable weight. A VC10 or Super VC10 ex-Nairobi could therefore carry a full load to Europe, a 707, even a fan-engined 320B/C, simply could not.

When Nairobi’s runway was extended to 13,000ft in the late 1970s, the 707s gained a little extra in payload ability at the expense of a longer, faster and riskier take-off run (in terms of speed, tyres, brakes and rejection distances). Overboosting the engines might also be required – with consequent costs, and operating risks. At such a ‘hot and high’ runway, a 707 might require a 40+ seconds take-off run and at least 10,500ft of tarmac; a later long bodied DC-8 or early 747-100 might require a fifty seconds take-off run of 11,000 ft +. Only at somewhere like Kano or Nairobi, with a take-off temperature of 35º C, would a heavily laden VC10 require over 6,500ft of runway to ‘Vr’ – to get airborne. In many locations a VC10, at reasonable local air temperature, could get airborne in around twentyfive seconds and use perhaps a third less runway distance than other types to ‘Vr’ – a unique performance for a very big airliner. Using less thrust on take-off to save fuel did, of course, mean using more runway tarmac. Lightly laden VC10 take-offs in just over 2,000ft were recorded and the author witnessed a partly fuelled RAF VC10 rotate in under 2,000ft at Kemble airfield. Try that in a 707!

Even in temperatures of 20º higher than those set by the international rules for safe runway length calculations, a VC10 could get airborne with a full load in much less distance than a 707 or a DC-8 carrying a reduced load could manage. The Super VC10 did, of course, trade runway performance for payload, but was still able to offer unique take-off and payload performance, and could get off the ground and to 35ft ‘screen’ height datum’ in 2,000ft less than a 707-320B.

In the early days, the BOAC Standard model VC10s were also a regular sight across the Atlantic, then the Super model took over. Of note, after the phased VC10 withdrawal, British Airways kept a spruced up, low-hours, Standard VC10 (G-ARVM) in reserve at London Heathrow in case the Super VC10 scheduled for a Blue-Riband service to JFK, went technical.

Cool Command Post

Although perhaps an ‘elite’, the fact was that the VC10 was easier to fly than a 707, and so the claim by 707 crews that they had been chosen to fly the more difficult machine due to their superior abilities, gained a bit of footing. Again, we can say that both aircraft were different and required different pilots who developed different skills. One thing was for sure though, the tightly cramped confines of Boeing’s very narrow and hot ‘cockpit’, with its shallow windscreens and ‘view out of a bath tub’ feeling, was far exceeded in terms of pilot comfort, air conditioning, fatigue resistance and visibility, by the vast space of the VC10’s deep-windowed command post with shoulder room to spare – a true flight ‘deck’ of maritime proportions. Crews were not up close and personal in the VC10 control post, whereas the two pilots sat close side by side in the 707, with the engineer behind.

VC10 pilots were also an early example of multi-type rating, as they were allowed to qualify for the Super VC10 too, both aircraft sharing nearly everything in common. Only the longer front fuselage of the Super VC10 needed to be cautioned over during taxying – with the nose wheel placed well back, the long nose had to be steered deep into turns, often hanging out over the grass. There were some minor speed differences and flap/slat/gear behaviours that were changed for the Super VC10, and of course the uprated Conway 550 engines had more power, the aircraft itself was heavier and the doors were in a different location. None of which could stop a ‘Standard’ model VC10 pilot from piloting a ‘Super’.

BOAC built up a pool of over 180 VC10 captains and senior first officers, with young trainees from the Hamble flight college being guided along their VC10 career path.

BOAC Boeing 707 cabin crews thought they were the elite – and on long-haul round-the-world sectors lasting three weeks, with rest days spent in five star hotels, who could blame them. The early celebrity culture of California and the USA saw film stars and pop stars as regular BOAC 707 guests across the Atlantic. BOAC used the 707 on the Tokyo and Sydney routes, but the Super VC10 got to Sydney in the end.

The Standard model VC10 flight and cabin crews knew that they were operating the special aircraft and made Africa and Asia their own, and soon began to enjoy postings on the Super VC10 and the new trans-Pacific routes and stop-overs. In general, it was a friendly BOAC ‘club’ atmosphere, although amongst both flight and cabin crews, there were a few people on the flight deck and in the cabin with that British ‘attitude’ as a snobbish sense of self-entitlement and grandeur. They were, however, often brought back down to reality.

L.R. 1, L.R. 2 and Super VC10

The VC10 was ripe, not just for engineering development, but also for swish marketing and the targeting of premier transatlantic routes. VC10s had traversed the Atlantic, but a bigger, or rather a longer VC10, something even more ‘super deluxe’, painted in blue and gold and loaded up with high fare paying corporate ‘fat cats’, cigars, booze, smoked salmon and stylish stewardesses, was an airline executive’s and marketing man’s dream.

The Vickers Advanced Project Office was full of fertile minds and a longer, high capacity version of the VC10 had been considered early on in 1959 – as a stretched ‘Vanjet VC10’ iteration. But could the ‘stretch’ of the airframe be made to create an almost new version of the original? Could the VC10 contain enough reserves of performance and lifting ability to be reconfigured into a 200-plus seater for use on the much easier transatlantic long-haul routes to New York and to Los Angeles, San Francisco, Vancouver, or across the Pacific – or on Polar routes? Surely a bigger VC10 could sell to many airlines, and make a valid base for a pure-freighter? Either way, the bigger VC10 would, along with the DC-8 63, be the longest, single-aisle, non-wide-bodied airliner in the world.

The idea of a bigger VC10 grew inside Vickers – to sacrifice some of the VC10s over-performance to add weight in the form of a much longer fuselage and extra fuel tankage. This would reduce the VC10s ‘hot and high’ runway performance yet gain payload and improved economics. A longer, heavier VC10 variant might need 8,000ft or more of runway to get airborne fully loaded on a warm day, but that did not matter, as the aircraft was not intended for short runway routes in the tropics – the VC10 itself catered for that role. The runways at Los Angeles and New York then offered 14,000ft+ for 707s and DC-8s!

So it was that a bigger, heavier, long-range (L.R.) VC10 – as ‘Super’ VC10 – was conceived; the range would be 4000 miles and the cabin might seat 212 or even 220 passengers, and the aircraft would, with the advanced wing design, still have better runway performance than the 707-320 or a proposed ‘stretched’ 707, or the DC-8-60 series, as long-bodied rivals.

Vickers funded a series of stretched, Super VC10 design drawings and models as project studies – as early as 1960 – and BOAC would soon order a large fleet of Super VC10s as longer-bodied variants.

Vickers were also working on a 265 seater VC10 ‘Superb’ iteration – with a double-deck fuselage suggestion – a vastly expensive retooling of the entire forward and under fuselage design.

Unlike other ‘stretched’ airframes, the VC10 did not need a larger tail fin, or major changes to its aerodynamics to cope with the effects of increased fuselage length and subsequent potential handling and performance issues in flight. As the engines were closely grouped, increasing the thrust levels had no effect on the aircraft’s behaviour in the manner that might afflict a wing-pylon mounted engine design with issues of wing strength and the asymmetric handling case of a failed engine. No expensive structural reworking would be required. In other words, the basic design was so good it contained all the reserves needed for more to be asked of it and retain most of its payload and runway performance.

Early on Vickers wanted to extend the VC10 fuselage by 30ft, but then settled on 28ft (Douglas were planning a 38ft stretch over their original DC-8 fuselage). Fitting the developed Conway engines, each with 22,000lbs thrust (24,000lbs was mooted), would allow a max-payload range formula to carry enough weight from London to New York, Washington D.C., or Boston, with 200 or even 212 passengers in a dedicated route-specific Super VC10 specification. Vickers also reckoned it could add underfloor fuel tanks and leading edge or trailing edge wing fillets housing 250 gallons or 500 gallons of extra fuel, and these ideas were initially the VC10 ‘L.R.1’ and ‘L.R.2’ types. Wing tip fuel tanks were also considered, but in the end the idea of making the large tail fin area ‘wet’, by filling it with over 1,000 gallons of fuel, was the route followed. The only issue here was the extra weight it inflicted upon the Super VC10’s centre of gravity. Vickers drew up plans for a 200 seater ‘Super VC10 200’ (to become ‘Super VC10’ as nomenclature) and the more specific 212 seater option. Larger cabin doors were suggested to aid passenger handling and emergency evacuation. With the benefit of much lower seat per mile costs, surely even BOAC could see the advantages of a non-Africa, non-’hot and high’ VC10 re-engineered iteration for easier routes where weight, altitude and temperature were less crucial? The stretched VC10 would also make a superb all-cargo freighter.

BOAC were indeed interested in a more economic variant of the VC10 – something less ‘hot rod’ and more of a liner. The issue was that the 212 seater still might not be able to fly from London Heathrow to the US west coast. Could the 200 seater Super VC10 200 manage it? LR1 and LR2 could have. But then BOAC suggested a more modest Super VC10, and had the idea of watering the concept down so that the new, higher seat capacity Super VC10 could still be used on more difficult BOAC routes. It seemed to be another BOAC paradox, wanting a more economic, higher capacity Super VC10, but then demanding that such a formula was watered down so that the new airliner could still retain capabilities on routes that it was specifically designed – or redesigned – not to perform on! Vickers were frustrated again; here was the bigger VC10 to tackle the transatlantic routes that BOAC had wanted, but BOAC wanted a smaller, bigger VC10!

What one earth was the point of a dual-ability Super VC10 that was neither fish nor fowl? Such a machine might not tackle the seat per mile cost operating economies of the larger 707 and DC-8 as well as could otherwise be managed.

It will come as little surprise to know that exactly such a VC10 variant became the BOAC production-specification Super VC10.

Vickers met the BOAC demand and added a lesser 13ft (as opposed to Vickers planned 28ft) to the Standard VC10; this was done via two fuselage plugs – one behind the wing and one in front of the wing and the only significant structural change was the repositioning of the existing cabin doors and inserting a rear cabin door. The details of the Super VC10 design changes were fundamentally simple.

SVC10 LR with Extra Tanks.

Super VC10 Design Changes

• 156 inches fuselage extension

• 75 inches between forward fuselage and 81 inches at rear fuselage

• Structural ‘Keel’ member stiffened to take longer forward fuselage loads to avoid ‘nose-nodding’

• Top skin fuselage panels thickened in strategic locations

• Curvature changes to nose-fuselage joins

• Increases to metal gauges in wings and wheel well locations

• Strengthened landing gear side-stay frame and reinforced landing gear

• Fin fuel tank structural skin ‘wet’ fin with 1,350 gallons/6,173 litres capacity with force-feed ram air

• Change to outboard wing fence and additional mini fences and vortex sections

• Maximum speed for 45º flap increase to 184kt

• Addition of rear fuselage cabin door: deletion of mid-cabin door

• Forward cabin doors and service doors repositioned

• Rear cargo door relocated

• Minor cockpit and crew station layout changes

• Forward galley and toilet location changes

• Engine nacelle angle changed by 3º and four thrust reversers (two alter deleted due buffet to tailplane)

• Uprated Conway ‘B’ engines on wider stub wing to 11in and re-shaped pods

• Interior trim changes

• Up to sixteen First Class seats

At 171ft 8in/52.32m long and a maximum take-off weight of 335,000lbs/151,958kgs, the Super VC10 was the biggest and heaviest airliner ever made in Europe at that time. It was also the most powerful until the later model Boeing 747 with RB211 524 engines. The VC10 and Super VC10 were the fastest airliners of their era with a high-speed Super VC10 cruise speed of 505kt/582mph/936km/h at 31,000ft/9449m. Higher altitudes (36,000ft+) saw both VC10 and Super VC10 exceed the 600mph/966kmh figure. The Super VC10 was up to 15kts faster in the cruise than the 707-320B thanks to the aerodynamic advantage – but the Super VC10’s added weight meant a touch more fuel burn once settled into that longrange cruise.

After the Super VC10 went into service with BOAC, it was discovered that by managing fuel flow demand between wing tanks and the fin tank, and causing a weight shift that markedly improved performance because it affected the aerodynamic stance of the airframe – its attitude (longitudinally). Through this the Super VC10 could be trimmed nose down or nose up – a bit like the old prop-liner ‘on the step’ attitude trimming. Previously, the VC10’s tail plane incidence setting (TPI) was used to trim the attitude prior to take-off, but the new fuel weight trimming by fuel transfer allowed a more variable in-flight trim updated. Concorde latterly used fuel weight transfer tank management for trim improvements between subsonic and supersonic flight.

Super Days Out

BOAC ordered the Super VC10 design as their definitive Super VC10 and used it to create a marketing offering for the transatlantic runs, but the chance of 200 seats and even lower costs had been lost (the DC-8 60 series would fill that gap). The first Super VC10 test flight was on 7 May 1965; just one month after the Standard VC10 had entered service. By 1 April 1966, Captain Norman Todd flew the first Super VC10 revenue service to New York JFK and the gleaming dark blue and gold aircraft then wowed US customers in a series of North American sales tour and PR flights – real red carpet affairs where the Super VC10’s quiet cabin, smooth flight, and soft landings astounded the industry and travelling public alike. It was in 1965–1966 that the short-lived ‘BOAC-CUNARD’ liveried Super VC10s plied North Atlantic skies – reflecting the commercial tie-up between the two great organisations. By the end of 1966, the idea had been quietly dropped and full BOAC titles returned to the smart blue noses of the fleet.

By the end of 1965, Super VC10s were serving Kingston, Nassau, Montego Bay and Bermuda. The Caribbean service also featured an often forgotten, oncea-week extension to Lima. Soon, San Francisco via JFK and Colombo, were all soon Super VC10 territory and, by early 1966, Super VC10s had replaced 707s on BOAC’s Chicago service. New Super VC10 routes were opened up into 1966–1969 with services to Perth, Western Australia (Sydney came afterwards), Pacific routings, and a vital new service from Manchester and Prestwick to North America – including Antigua in the Caribbean. The 21 September 1968 saw the Super VC10’s longest non-stop flight sector of 4,420 miles being launched from London to Barbados. October 1969 saw the launch of BOAC’s true, round-theworld by Super VC10 service – being westbound from London to New York, Los Angeles, Honolulu and Fiji, then to Sydney.

However, even the Super VC10 lacked the range for a non-stop Heathrow to Los Angeles routing, but that did not stop BOAC routing them via Chicago to Los Angeles and thence across the Pacific on the round-the-world service though. A Super VC10 Vancouver routing via Montreal was an occasional delight – it usually being the preserve of a non-stop 707.

Standard model VC10s were in regular movement across the Atlantic in the early days – then the Super model took over. The shortest scheduled VC10 service operated circa 1970 on the connecting service from Bahrain to Dhahran. The two airfields were twenty-five miles apart, with the runways more or less in line. This was one of the shortest flight timed sectors of just eight minutes airborne. If a BCAL VC10 diverted into Heathrow from Gatwick due to weather, or BOAC did the same into Gatwick from Heathrow, the (direct) flight time to recover back to base would be about ten minutes. The author witnessed two very short RAF VC10 flight sectors in 2013 – Brize Norton to Fairford, four minutes flying, and Kemble to Brize Norton with seven minutes flying at minimal fuel weight after a 1,850ft take-off run!

In terms of the longest VC10 flights, the Super VC10 could manage over nine hours in flight with a nine hour fifty minutes endurance in typical flight conditions – depending on winds and allotted heights (but with possibly lower fuel reserves). One Super VC10 (G-ASGO), on the popular run from London Heathrow to Barbados, was airborne for nearly ten hours (9h 55m) in January 1971, with the aircraft having step-climbed to 41,000ft and effectively saving fuel over the planned route and avoiding a ‘tech’ stop. In the winter, the route would more normally operate via New York or an eastern seaboard runway.

The Super VC10 London to Seychelles came on line in 1972 and was one of the last new BOAC Super VC10 routes. This was developed into an Entebbe-Nairobi-Mauritius-Seychelles service with an onward, trans-Indian Ocean crossing to Colombo-Hong Kong-Tokyo service on a twice weekly basis. It was very popular with crews and passengers alike. A joint South Africa-Seychelles-Hong Kong service was created with South African Airways code-sharing on BOAC machines (SAA would later lose one of their 747’s over the Indian Ocean on this service). BOAC’s Super VC10s were hard worked by this time with a twelve hour flying day being the norm. Yet, as early as the spring of 1972, Super VC10s were being usurped across the Atlantic on the Chicago service by the 747-100 in BOAC colours.

According to BOAC’s own official statement of accounts in 1971, the Super VC10 fleet had worked twelve hours a day, every day (in the air), by flying 70,347 hours at an average of 4,387 hours per airframe. Super VC10 costs per capacityton-mile were lower than the Standard VC10 fleet, but BOAC did not publicise a mixed-fleet cost per fleet comparison. In 1971–1972 we do know, however, that the BOAC Super VC10 fleet achieved an annual utilisation rate of just under 4,500 hours per aircraft (4,397 hours) which was seventy-five hours more than the best ever figure achieved for the Standard VC10 fleet and several hundred hours more than the VC10 fleet average figure.13

We also now know that the Super VC10’s hourly flying costs were, on occasion, less than the BOAC’s 707s; we should recall that unlike the 707 fleet, the Super VC10 could not rely on other airlines having operational and maintenance/repair support facilities. The Super VC10 was on its own and needed to achieve better reliability than its rival. From 1970–1974, two Super VC10s were lost (on the ground) to acts of air piracy and the type suffered a rash of hijackings in 1974 – maybe terrorists or freedom fighters, call them what you will, preferred the Super VC10!

The VC10 and Super VC10 fleets were integrated with dual-type crew ratings and cross-working by cabin crews. Over 300 VC10/Super VC10 fleet pilots, 120 engineers, 260 stewards and 250 stewardesses were employed by BOAC. A final fleet of twelve Standard VC10s and seventeen Super VC10s was reached in early 1969. Vickers had delivered the machines in a very short time indeed.

From 29 April 1964 to October 1976, the BOAC/BA Standard VC10 flew a revenue-earning 409,405 hours, and the Super VC10 fleet, from 1965 to March 1981, flew 797,791 flying hours and never caused injury or death. VC10 G-ARVM was the last of the fleet to be built and the last to remain in BA service beyond 1976. The Super VC10’s last scheduled commercial airline flight was from the Indian Ocean islands to Dar-es-Salaam and Larnaca to London Heathrow with Captain Sanders making the final landing, and took place on 29 March 1981 with G-ASGF ending the BOAC/BA VC10 and Super VC10 story. There followed at least two chartered enthusiasts flights around the UK airports and BAC factory sites over the next few days. On board one, was Ernest Marshall, VC10 chief project engineer, who had been there at the aircraft’s birth pangs.

The BOAC Super VC10s (Type 1151) were registered G-ASGA to G-ASGR. East African Airways (EAA) were the only other Super VC10 operator and their (Type 1154) Super VC10s had a forward fuselage cargo door and a reinforced floor – so they were heavier. They also benefited from every tweak and upgrade learned during the VC10 and BOAC Super VC10 production series, and as they were fully painted, were a touch more smoothly finished – but paint weighed extra! The EAA machines were lavishly trimmed inside and out and carved their own niche in African aviation history. The fact of the Nairobi-Zurich-New York Super VC10 service being seen at JFK alongside the BOAC Super VC10 service would have been a sight for the men of Vickers as the 1960s ended and the decade of the 1970s began.

But all this was in the afterwards. Before, in 1965, BOAC was carping and cancelling about the VC10 and Super VC10 – the machines it had requested to its own needs – effectively setting the design parameters by default.

Maybe the resulting Vickers products, the VC10 and Super VC10 were ‘Rolls-Royces’ of the air – or a sportier version like a Bentley or an Aston Martin! However, it seemed BOAC had now decided ‘after the fact’ that what it really wanted was a Ford Cortina, or should that be a Ford Galaxie.