The Tay Viscount (630) of 1950, following on from the Nene Viking this was the true precursor of Vickers jet airframe design and development. From here stemmed the Vanjet and VC10. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

The Tay Viscount (630) of 1950, following on from the Nene Viking this was the true precursor of Vickers jet airframe design and development. From here stemmed the Vanjet and VC10. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

The lost future: V1000 (VC7), 85% complete and just months from a world-market dominating position yet killed off by external players, thus handing global advantage to Boeing and Douglas respectively. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

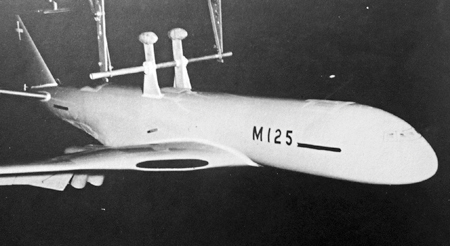

This Saunders Roe V1000 hydro-dynamic development test model shows off the airliner’s advanced design and lines that look far more futuristic than found in desktop models and plan drawings. A nose gear hydroplane was suggested to reduce the ‘diving’ effect in a ditching. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

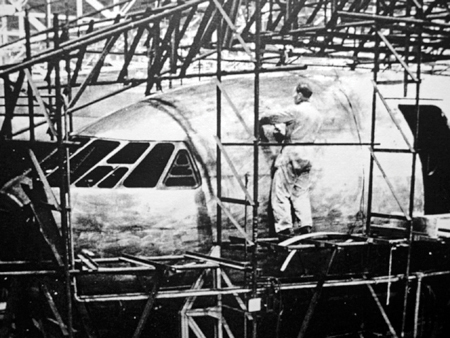

V1000’s cockpit window and nose design show clear hints of later VC10 motifs. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

Vickers Managing Director Sir George Edwards (left) and BOAC’s Sir Basil Smallpiece sign-up for the demanding ‘Empire’ route specification airliner in January 1958. Vickers top man, Air Commodore Tuttle is out of shot. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

Vickers Advanced Projects Office at Weybridge (Brooklands) with leader Ernest Marshall flanked by John Davis (left), Maurice Wilmer, Sammy Walsh (both to right), ‘Jock’ Swanson to rear. This is where the genius of Vickers design was born. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

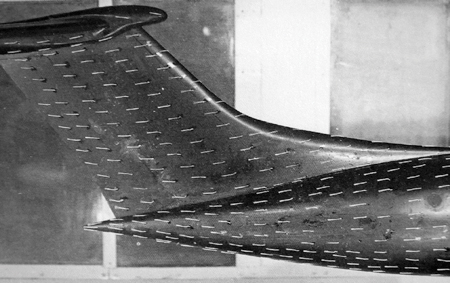

VC10 aerodynamics development – tuft testing the crucial T-tail airflow. Hours of work went into lessening the deep-stall potential. The elegant swan-like bullet fin-top fairing also resulted. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

VC10’s reinforced nose structure – this is the flight deck. Note the closely spaced ribs, and thick support structure around the apertures. Truly built like a Vickers battleship! (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

Rear fuselage details: note engine cross beams, (to which the ‘spectacle’ engine bearer supports were mounted), tail fin hoops, extra cleats, thickened gauges and over-engineered strength. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

Flightdeck: VC10’s command post was much roomier than the 707’s tight confines. Seat ingress and exit was outside the seats, not beside the centre console as in 707. Deep windows improved the view. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

Super VC10 shows off the T-tail and design features. Note extended stub wing pylon for the engines and ‘beaver tail’ exhaust fairings. The true height of the fin compared to other T-tailers is obvious. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

The early pre-delivery BOAC livery seen on G-ARVB as test-airframe – without the production series inboard wing fence that Bryce and Trubshaw insisted upon to cure spanwise flow issues at low speeds. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

The Royal Air Force was VC10’s other main operator. This stunning shot of a C.Mk1 in action photographed from another VC10 shows off the airframe in-flight in period style. (Photo: S. Ludlow)

Going up: G-ARVM, the last Standard-model BOAC VC10 blasts out of Vickers Weybridge site (Brooklands) in 2,150ft to ‘Vrotate’. The livery would soon change again. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

The Super VC10 during build in Weybridge site’s ‘Cathederal’ main construction hall; Vickers employed over 7,000 people. Note the rare, soon-to-be revised early BOAC livery. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

East African Airways Super VC10 5X-UVA in all its glory – with the cargo door open. First Class was ahead of the cargo hold and Economy Class aft. A walkway through the cargo had to be kept clear, despite that caveat, this added ‘combi’ feature was highly attractive to airlines.

BOAC’s Captain Peter Cane at the controls of G-ARTA as VC10 development pilot during 1963–1964. Cane was in the right hand seat when Brian Trubshaw had trouble on an early test flight. A BOAC VC10 holds the world record for the fastest time taken for a subsonic airliner to have crossed the Atlantic, in a time of five hours and one minute; a record that stands to this day. The second fastest time recorded also belongs to the VC10, at five hours and fifteen minutes! (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

BOAC became British Airways in 1974 and the Super VC10 gained the new livery in full. It lacked the style of the Speedbird design but retained the quintessential emblem on the upper forward fuselage. BA’s last SVC10 commercial service was on 29 March 1981. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

Mr Laker’s hard-worked British United Airways VC10 with the revised wingtips and the forward fuselage cargo door. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

British Caledonian VC10s had a lion rampant on the fin. BCAL served South America and Africa with its VC10s prior to deploying 707s. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

East African Airways truly “Super” SVC10s looked even longer in the striped livery. This is the illfated 5X-UVA that was lost at Addis Ababa in a take-off accident that was not the fault of the pilot nor the aircraft. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)

RAF VC10 CMk1 grabs at the sky after using just 1,950ft of runway to ‘Vrotate’. Full power, nose high, and performing like a fighter not an airliner. This was the true VC10 advantage; the 707 and DC-8 simply could not match this feat. (Photo: L. Cole)

The T-tail, rear-mounted engines and generous slat and flap on the ‘clean wing’ design are shown off in the RAF’s ‘hot-rod’ VC10: real elegance. (Photo: A. Hart)

The ‘face’ of the VC10’s Vickers design, stemming from Vanguard and Vanjet design studies. A rarely appreciated angle to the fuselage roof structure is captured here as the RAF C.Mk1 poses for the camera just months before the type’s demise. (Photo: L. Cole)

Fire up the Vickers! Another view of the updated RAF VC10 C.Mk1, reveals the upper and lower fuselage contours, ‘chined’ nose gear tyre, sleek wing box join, and that T-tail with its elegant ‘bullet’ fin top fairing; pure VC10 style as the RAF get ready to rev up the Conways. (Photo: L.Cole)

Doing the business. An RAF Harrier feeds from an ex-EAA Super VC10 as the Conways hum and the fuel flows. (Photo: L. Cole)

In-flight: on-board an RAF VC10 during refuelling exercises; the generous space and view from the flightdeck are evident. (Photo: L. Cole)

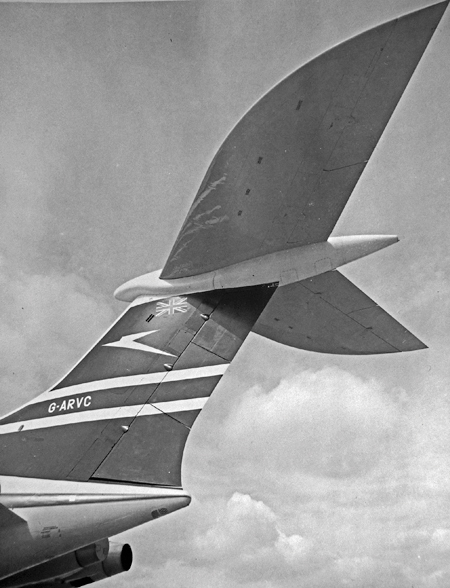

The greatest tail – ever! The magnificent VC10 tail design from Ken Lawson’s aerodynamics team. Note the original, curved shape to the lower rudder’s trailing edge – changed to an angled shape for later production airframes. Unlike most other T-tailed airliners, VC10 never suffered from a deepstall and VC10 had natural nose-down pitch at the stall, but a stick-pusher was still an advisable fitting to avoid trouble in certain flight configurations. (Photo: Vickers/BAC)