3

Enslavement

[Odysseus wept] As a woman weeps, lying over the body of her dear husband, who fell fighting for her city and people as he tried to beat off the pitiless day from city and children; she sees him dying and gasping for breath, and winding her body about him she cries high and shrill, while the men behind her, hitting her with their spear butts on the back and the shoulders, force her up and lead her away into slavery, to have hard work and sorrow, and her cheeks are wracked with pitiful weeping.

Homer, Odyssey 8.523–30, trans. Lattimore 1965

Introduction

When students first hear about slavery in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, they sometimes assume that only black Africans were slaves and wonder how the Greeks would have obtained slaves from the sub-Saharan regions. Students fall into this error because the predominant image of slavery today is of the enslavement of Africans in the New World. Although features of better known, modern slave systems sometimes help us understand, or at least imagine, aspects of ancient slavery about which we have little evidence, we cannot assume that just because something was true of New World slavery it was true in the ancient world. People of any race or ethnicity can be enslaved – and most have been at one point or another.

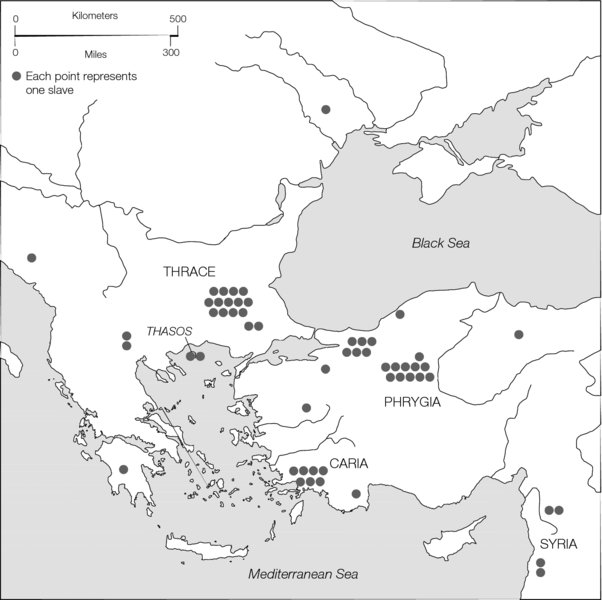

Most slaves in classical Greece came from Thrace, the Black Sea area, and the eastern coast of the Aegean (Map 1; cf. Map 4 below). Some came from Syria and Egypt. In fact, one typical slave name in comedy was Xanthias, which means “Blonde.” This may reflect the northern provenance of many slaves. Greek comedy gives us additional evidence. Comic actors wore standard masks that stayed the same over the generations. Slave characters in comedy wore masks with red hair attached. This convention probably reflects a time when the stereotypical slave was imported from the north and had red hair – or, more probably, had red hair more often than the Greeks themselves did. Slaves in classical Greece were generally ethnically different from the Greeks, but they were rarely African.

Map 4 Origins of slaves at Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. The slaves attested on inscriptions at Athens rarely seem to be Greek. Rather they come from areas like Thrace, on the outskirts of the Greek world, and from the western provinces of the Persian Empire, such as Phrygia and Caria. From The Cambridge World History, Volume 4, ed. Craig Benjamin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 91, Map 4.1, based on Morris 1998, figures 12.2 and 12.3. Source: Morris 1998. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

In the Hellenistic period, dark-skinned African slaves were imported from Nubia, south of Egypt, into Ptolemaic Egypt. Several famous works of Hellenistic art depict such slaves, but they seem to have been a small minority of the slave population. Images of dark-skinned African slaves may be overrepresented in art, since they appealed to Hellenistic artists and patrons interested in exotic and unusual subjects. Most slaves, however, again came from other Hellenistic kingdoms and their borderlands and not from Africa.

Roman slaves came from a wide range of areas at different points in Rome’s expansion and its empire. Many slaves would come from those areas where the Romans were currently fighting or where their wars and conquests had left lawless and chaotic conditions, but the slave population was always a mixed one, with some slaves coming from one area and others from another. The regions that supplied Rome with slaves included at one point or another virtually the whole of Europe, northern Africa, and the Near East.

The answer to the question of where, geographically, slaves came from is, thus, a complicated one with large variations over time. More important and just as complicated is the question of how previously free people ended up in slavery. Enslavement in the ancient world could come about in many ways, and it will help to outline these possibilities. First, however, let’s address a red herring. Some historians describe importation as a source of slaves both in classical Greece – where slaves could be called “bought barbarians” – and at Rome. Importation is a source of slaves in one sense but not in another. Importation explains how a Roman senator, for example, obtained a particular male slave: he bought him from a merchant who had imported him from, say, Bithynia on the southern coast of the Black Sea. Importation does not, however, explain how this free inhabitant of Bithynia, to continue our example, became a slave in the first place. This question of how previously free people ended up in slavery can be particularly hard to answer since the original enslavement often took place on the fringes of the classical world, out of sight of the Roman senator in our example, and in a place for which our sources of information can be almost non-existent.

Importation does bring up an important distinction among ways that people became slaves: some types of enslavement involved people from a society becoming slaves in that same society; other types involved the forcible migration of people to another society, more or less at the same time as their enslavement. We’ll consider first the ways that people could fall into slavery within their own society, a less common occurrence, and then the methods of enslavement that involved concurrent transfer between societies.

In many periods and places, people could fall into debt bondage. This occurred when people took out loans on the security of their labor or person – in the same way that a mortgage today is a loan taken out on the security of a house. In the event of default, it was the creditor who typically set the terms of this labor. So it is rare for people ever to escape debt bondage: their labor is often counted as merely offsetting the interest on their debt. In this way, a debtor can end up obligated to life-long, full-time, involuntary labor. Despite these grim prospects, people in debt bondage are not generally considered slaves, since they can’t be sold, the status is not hereditary, and they can continue to live with their families. In some cases, however, a debt bondsman became the creditor’s property and, in particular, could be sold away from his home and family. Some historians identify this last situation, when the debtor has become a chattel slave, as debt slavery instead of debt bondage. Debt bondage was common throughout the ancient world but only occasionally was it a major path to slavery.

In the ancient world, unwanted infants were left out to die, “exposed.” It is surprising to modern expectations that even at places and times where abortion was considered immoral, the exposure of infants was accepted – by our male sources at least. One explanation is that abortion was censured as a woman’s usurpation of a father’s right to his offspring whereas it was traditionally the father who decided whether a child was exposed, and thus this practice was acceptable (Oldenziel 1987, 100). Exposure provided a source of slaves because, if somebody found and took care of an exposed child, they could raise him or her as their slave, since the reassertion of free status was legally possible, but unlikely in practice. Some people may have even made a living by regularly checking the places where babies were typically exposed and taking some of them to care for and raise as slaves. Both of these types of enslavement, through debt and through exposure, involved a person being enslaved within their own society, but once somebody was a slave they could be sold anywhere.

Turning to the other category, enslavement outside of a person’s society, war captives were often enslaved. This was not an inevitable result of military defeat. For example, the defeated state would often accept peace terms, and victors often preferred a subject state to mass enslavement. Nevertheless, the evidence is overwhelming that Greek and Roman wars produced many slaves. Not only could soldiers be captured, but, when armies ravaged an enemy’s countryside or sacked a city, they often captured and reduced to slavery many civilians. A similarly violent, but smaller scale, source of slaves was the activity of pirates and kidnappers. These thrived especially in places and periods lacking strong states with an interest in maintaining order – especially states with naval power. In the late Republic, tens of thousands of war captives were regularly imported to Italy; in addition, the chaos in the Eastern Mediterranean – where humbled and defeated states could no longer field strong navies to protect trade – also encouraged piracy and consequently enslavement on a grand scale. For example, an ancient source claims that one group of pirates was capable of mustering a thousand ships and that the slave market on the island of Delos was capable of handling the sale of ten thousand slaves each day, many of them the victims of pirates (Strabo, Geography 14.5.2).

Our discussion so far does not imply that all slaves were born free and then enslaved; many slaves were born into slavery. The general rule about the inheritance of status was that – in the absence of an official marriage, which slaves could not contract – a child had the same status as his or her mother. Thus, children born to slave women were slaves regardless of the status of the father – who was sometimes the woman’s owner, as we shall see in Chapter 7. Later I’ll consider the controversial topic of what proportion of Roman slaves were born in slavery in different periods.

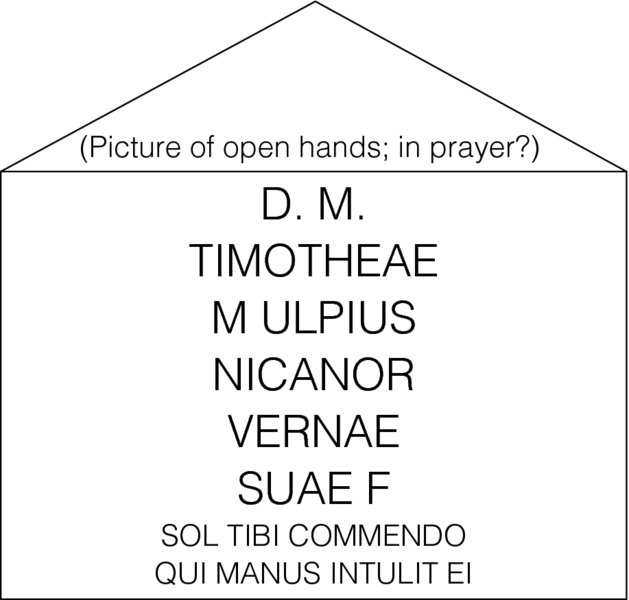

The way an individual was enslaved was important to his or her life; the way most slaves became slaves affected the way the whole institution of slavery operated within a given society. Most obviously, if the slave population could not reproduce itself, then new people needed to be enslaved each generation, if slave numbers were to remain constant. The process of enslavement is usually a violent process, which was almost indescribably wrenching for the persons enslaved. In addition, the whole texture of relationships between masters and slaves was affected by whether few, some, or all of the slaves are born in slavery. To take just one example, relations between masters and slaves as well as among slaves are profoundly influenced by whether or not they all speak the same language. And, in Chapter 10, we’ll see that a high proportion of new slaves was a factor that made slave rebellions more likely. In contrast, both Greek and Latin had special terms for slaves born in a master’s household, probably reflecting a time when such slaves were relatively rare: both the Greek and the Latin term (verna) imply something like “home born” or “native born.” And, in general, such slaves were considered well behaved and loyal: some of them had close ties with their masters, attested in epitaphs put up by Roman masters to their beloved vernae.

Figure 3.1 Epitaph of Timothea: “To the sacred spirits. For Timothea, his verna, Marcus Ulpius Nicanor made [this]. Sun, I give over to you [for punishment] whoever attacked her.” The slaveholder Nicanor took a familial interest both in the commemoration of Timothea, his deceased verna, and in obtaining vengeance for her – through the Sun god – since she was apparently a victim of violence. Historians agree that there must have been far more home-born slaves in Rome than are identified as vernae on their epitaphs; presumably, the designation was confined to those home-born slaves who enjoyed some intimacy with their masters. The owner’s name, Nicanor, is Greek, as was common among slaves, ex-slaves, and sometimes their descendants at Rome (see Chapter 8). His full name suggests that he may have been an ex-slave of the emperor Trajan (born Marcus Ulpius Traianus) or a descendant of such an ex-slave (see Chapter 5). Source: Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museum, CIL 6.14099. Line drawing from VROMA: http://www.vroma.org/.

The source of slaves is closely related to the ratio of males and females among the slave population. In the New World, slave systems that depended mainly on new slaves, such as those of Brazil and the Caribbean, tended to depend mainly on male slaves, who were more capable of heavy labor and thus commanded a higher price after being transported across the Atlantic – conversely, women slaves were in high demand in Africa (Lovejoy 2012, 14, 63–64). This unbalanced sex ratio in Brazil and the Caribbean limited natural reproduction among the slave population, since the birthrate depends on the number of fertile women. In the American South, however, by the time the importation of slaves ceased in the nineteenth century, a natural population containing approximately equal numbers of males and females had reasserted itself. This sex ratio, in turn, made it possible for the slave population to reproduce itself and even to grow without any new source of slaves. To understand how the institution of slavery worked in any place and period, it is crucial to determine whether it followed one of these patterns or something intermediate.

The ethnic origin of slaves also influenced the institution. It especially affected how masters thought about their slaves and justified slavery. Most notoriously, New World slavery was based on racist distinctions: according to most slaveholders, it was only black Africans who deserved to be in slavery. The peoples from whom the Greeks and Romans took their slaves could not be distinguished on the basis of skin color – which was not always easy even in the New World. Nevertheless, Greeks and Romans often expressed contempt for their slaves on the ground that they came from inferior cultures. When one Greek city enslaved the citizens of another, this way of justifying slavery was more difficult: Greeks generally felt they belonged to a single category in contrast to non-Greeks. As a result some strident critiques of slavery in the classical Greek world focused only on the enslavement of Greeks and not slavery in general (see Chapter 12).

During the second and first centuries BCE, many slaves at Rome were Greeks from mainland Greece and from the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Eastern Mediterranean. The Romans held Greek culture in high esteem and, in Chapter 6, we’ll revisit the issue of how the Romans dealt with slaves whom they in some respects considered culturally superior to themselves. In most cases, however, the Romans did not think highly of the people they enslaved. For example, Cicero complained that Caesar’s invasion of Britain was not likely to be profitable: there was no plunder to be had other than captives and, he snidely remarks, “none of those are likely to be well trained in music or literature” (Cicero, Letters to Atticus 4.16.7). This was probably a pointed contrast to the slaves of Greek background that might be expected from wars in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Where and how people were enslaved is, consequently, not an isolated aspect of a slave system. Even when historians cannot come to agreement about the dominant source of slaves in one period or another of Greek and Roman history, their debates contribute to our understanding of important aspects of classical slavery. In this chapter, we consider two case studies. First, an enigma surrounds the role of warfare as a source of slaves in classical Greece, especially Athens: why do we find mostly foreign (non-Greek) male slaves when we might expect Greek female slaves? Second, historians have long assumed a change in the main sources of slaves between the Roman Republic and Empire, a shift from war captives to born slaves, but this conclusion has been challenged. Historical demography, the quantitative study of human populations, has recently made decisive contributions to this topic.

Warfare and the Sources of Athenian Slaves?

Most slaves at Athens in the classical period were not born into slavery. Striking evidence of this comes from lists, inscribed on stone, of the property confiscated from a number of wealthy Athenians who were condemned for sacrilege in 415 BCE. These lists are known as the Attic Stelai: Attica is the territory of Athens, and stelai denotes the thin, rectangular stones, shaped like tall gravestones, on which the lists were inscribed. The Attic Stelai list the confiscated property which the state put up for auction, and tell how much it sold for and how much tax was levied. Among this property were slaves belonging to the condemned. The lists identify those slaves born into slavery with the word oikogenés, home-born, but only a small fraction of the slaves listed have that designation (Pritchett and Pippin 1956, 280–281). More of the slaves are identified by their place of origin: for example, “Potainios, a Carian” (Stelai 2.77 in Pritchett 1953, 251). All these places of origin are non-Greek. An even larger set of slaves have names that consist of ethnic expressions, for example, Thrax (Thracian) as a name. Of these ethnic names on the Attic Stelai, seventeen out of eighteen are non-Greek. This leaves only eight slaves with Greek names. Even they are not necessarily Greek given that some of the slaves whose origins are both specified and foreign had Greek names. Thus, the vast majority of the slaves on the Attic Stelai seem to have been born outside of Athens and indeed outside of Greece.

About a hundred personal names are found on inscriptions in the mining area of Athens, mainly on epitaphs or simple religious dedications. Many of these must be the names of mine slaves. That so many of the names are not Greek suggests, again, that more than half of such slaves were of foreign, non-Greek descent (Lauffer 1979, Table 6 (124–128), 140). Foreign slaves also predominate in comedy (Ehrenberg 1974, 171–173). In a law court speech, Demosthenes mentions the “barbarians (non-Greeks) from whom we import slaves” (Demosthenes 21.48). Finally, a couple of passages suggest that masters could not assume that an Athenian slave could even speak or understand Greek.1 Some of this evidence may not be dependable: for example, slave names may not reflect origins, and slave traders had incentives to misrepresent the origins of slaves belonging to less marketable ethnic groups (Braund and Tsetskhladze 1989, 119–121). Enslaving Greeks became an awkward and controversial practice – a topic we’ll revisit in Chapter 12 – and may be under-represented in our evidence as a result; for we do indeed hear anecdotes about Athenians and other Greeks falling into slavery. On balance, however, I am convinced that most slaves in Athens were neither Athenian nor Greek. But, of course, our sources are not such that we could venture a percentage for the non-Greeks among the slave population at Athens: was it 65 percent or 95 percent?

The brutal practices of Greek warfare seem at first to suggest how foreigners ended up as slaves in Athens. The first text in Greek literature, Homer’s Iliad, describes how, when a city is sacked, the men are killed and the women and children taken as slaves (e.g., Iliad 9.590–594). The tents of the Greek heroes outside Troy are filled with captive slave women, and a quarrel about one of them motivates the central conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon. In the simile with which we began the chapter, Homer pictures the scene of enslavement: a city’s foes drag a woman into slavery after having killed her husband. Homer presents a heroic version of eighth-century warfare, but occasionally this picture is confirmed by evidence from the classical period. Most infamously, when the Athenians defeated the small island of Melos, they enslaved the women and children and killed the men (Thucydides 5.116). Their notorious general, Alcibiades, even acquired a Melian slave mistress in the process. So far the picture seems to make sense: enslavement in war was a longstanding practice in the Greek world and continued to provide most slaves in the classical period when Greece had become a slave society. There remains, however, a big problem with this model: direct evidence about the slave population at Athens, the Greek slave population about which we know the most, does not match what we would expect of a population captured in war.

First of all, if the Athenians captured their slaves in war, Homeric style, we would expect a slave population consisting mainly of women and children from the states that Athens fought against. The slave population at Athens, however, seems to have contained more men than women. The Attic Stelai recorded 37 men to nine females. Statistically, such a skewed sample is almost impossible, if the actual ratio was 50/50, and if the Stelai provide a random sample of the slave population.2 I have a theory about one way that this sample may be biased: the wives of the condemned probably left their husbands and returned to their paternal homes taking with them some of their personal servants, predominantly female. So the property that remained to auction and be recorded on the Stelai contains fewer female slaves than were in the original households. There may be other ways in which the gender ratio on Attic Stelai is skewed, but it is striking that we also find predominantly male slaves in comedy, even though most comedies were set in the household: we expect female slaves to predominate among domestic slaves, but they are a minority even there.

By itself the unexpected sex ratio, more men than women, is perhaps explicable. Walled cities were rarely captured, so women were often safe inside, while men were the ones out fighting and thus at risk of capture. But difficulties remain. Athens fought wars against the Persian Empire during the first half of the fifth century, but for a generation before the Attic Stelai were inscribed, Athens’ main enemies were other Greek cities. But we find no slaves from any of these places: no Thebans, no Corinthians, no Lacedaemonians, no Aeginetans, and no Megarians. Rather, as you can see from Map 3.4, based on different types of inscriptions, slaves at Athens seem to come from a large variety of non-Greek areas in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea, with Thrace and the eastern coast of Asia Minor providing the largest groups. This data leaves us with two questions. First, why did warfare among the Greeks not provide more slaves? Second, how did non-Greeks end up as slaves in Athens if not as the result of capture in war?

I mentioned already that Greek walled cities were rarely taken by storm. Out of a thousand or so city-states, only a handful – such as Melos – would suffer this fate in a generation. This greatly reduced the potential for the enslavement of whole populations with women and children. Some soldiers could be captured and enslaved. In one exceptional case – the greatest defeat in known history according to Thucydides (7.87.5–6) – the Syracusans and their allies destroyed the entire army and navy sent against them from Athens and captured Athenians and subject-allies, in numbers in excess of ten thousand. Most of these ended up being sold into slavery (7.85.3; 7.87.3). Enslavement was not, however, the most common treatment of captured soldiers. Usually Greek armies kept such captives as prisoners of war. They might then return them to their cities for a ransom; for a captured soldier was usually worth much more to his own family, if they had the money, than on the slave market. In addition, city-states generally wanted to get their citizens back, so the peace treaties that ended most wars often required both sides to release the prisoners of war they had taken. Even though war was common and war captives were potentially liable to enslavement, warfare among the Greeks still could not provide a large proportion of the slaves at Athens.

The second question (how did so many non-Greeks end up in slavery?) is more complicated. The historian Theopompus wrote in the fourth century that the Chians were the first Greeks who used “bought barbarians” as slaves (Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters 265 C). This statement suggests two things: first, it confirms our impression that most slaves were non-Greek, hence “barbarians”; second, it shows that Greeks thought of contemporary slavery as marked by import rather than direct capture – hence “bought” slaves. But, knowing that the Greeks bought their slaves only provokes other questions: how did so many non-Greeks end up on the slave market, and why was it the Greeks who bought them?

War may still be at the root of Greek slavery but at one remove. Many people may have been enslaved in war and then imported to the Greek world. The areas on the outskirts of the Greek world from which slaves were imported to Greece were not usually of much interest to Greek historians, and they did not produce their own historians. Nevertheless, we do occasionally hear about wars among non-Greeks, for example, the various revolts of Persian governors against the King of Persia and the resulting wars. During some periods, these conflicts explain how so many slaves came into Greece from the western areas of the Persian Empire in Asia Minor, a major source of slaves. Our sources sometimes report wars between rival principalities in Thrace.3 It is safe to assume that other Thracian wars – especially those far inland – were not reported or even known by Greek historians. Such unattested wars could explain the many Thracian slaves at Athens.

The Greek demand for slaves may even have encouraged slaving in the hinterlands of Greek settlements on the coasts of Thrace and Asia Minor: as one historian puts it, “there seems every reason to suppose that the slave trade at the coast served to generate instability and conflict in the interior” (Braund 2011, 115). The sale of slaves to the Greeks was lucrative. Raids and wars became more profitable and perhaps more likely to occur once captives could be converted into cash or traded for desirable and otherwise unobtainable luxury goods from the Greeks. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Africa, this phenomenon was a well-known and devastating effect of the export of slaves to the New World. That it occurred also on the outskirts of the Greek world is likely enough.

Greek colonies, numbering in the hundreds, sometimes intervened directly and undertook slave raids against their non-Greek neighbors: for example, the Greek mercenary and philosopher Xenophon took part in such a raid, completely unprovoked, while on the northern coast of Asia Minor (Xenophon, Anabasis 6.3.2–3). Large numbers of these Greek cities lay in close proximity to non-Greek populations on the coasts of Thrace, Asia Minor, the Black Sea, Sicily, and Italy. Often the Greek city, a colony, was on the coast and had captured enough land from the natives for the settlers to farm but still faced a foreign hinterland. The sporadic raids or small wars of such cities with their neighbors may not make it into the historical record even if, in total, they resulted in the enslavement of many people.

A final possibility takes us away from war altogether. Recall that it was only with Solon’s reforms that citizens of Athens were secure from ever falling into slavery for debt. The non-Greek states from which Greece obtained slaves did not develop democracies and may never have curbed debt bondage. Quite possibly, poor Thracians or Lydians possessed so few rights that they could fall into debt bondage and, in some cases, even be sold away from their homelands. And Herodotus claims that the Thracians – presumably poor Thracians – sold their children into slavery (5.6.1). Slavery and sale abroad might also have become a punishment for criminals or for political enemies. This type of punishment for crime or simply for poverty would have become more attractive given Greece’s demand for slaves. Once there is a ready market for humans, some people will find ways to supply it and thus to profit from it.

So far we have treated the supply side of the slave trade; we’ll defer discussing the demand for slaves in Greece until we get to the economics and politics of Greek slavery in the next two chapters. For now, let’s turn to the Roman slave supply.

A Sea Change in the Roman Slave Supply?

In Roman law, “Slaves are either born or made” (Justinian, Institutes I.3). As we have already seen, people could be “made” into slaves in a variety of ways or they could be born into slavery. Historians have traditionally held that the many brutal wars of Rome’s expansion supplied the vast majority of slaves, “made slaves,” until the pace of conquest slowed during the reign of Augustus (31 BCE–14 CE). After this watershed, so the theory holds, the main external source of slaves was slowly shut off, the price of slaves increased, and Roman slaveholders turned increasingly to natural reproduction, “born slaves,” to replenish their slave labor force. Despite this expedient, the number of slaves slowly declined. Some historians have even sought the beginnings of serfdom in the decline in slavery and in the binding of Roman peasants to their land in the late Empire, from the third to fifth centuries CE. We shall return to this last theory in Chapter 13, but for here it is enough to say that this grand scheme of a transition from slavery to serfdom is much too simple. Here we focus on the traditional view of the Roman slave supply (Table 3.1) and whether it is generally correct.

Table 3.1 Traditional view of the Roman slave supply.

| Dates | Intensity of warfare | Proportion of war captives | Proportion of born slaves |

| 300–1 BCE | Higher | Higher | Lower |

| 1 CE to 200 CE | Lower | Lower | Higher |

Before we get to the main issues, one implication of the dates I have chosen is worth stressing. In this chapter, we are not concerned with what happened after 200 CE. From the vantage point of modern historians, centuries sometimes shrink, like cities seen from an airplane, and we may (falsely) assume that there was only room for one big trend in the slave supply under the Roman Empire. But the third through fifth centuries CE were different from the first two. Warfare again became more frequent and more intense. This warfare was obviously less successful than that of the Republic – after all, the Roman Empire suffered many invasions and eventually Rome was sacked and the western Empire fell to invaders – but it is entirely possible that enslaved war captives became more numerous again in the violent late Empire. In any case, over the whole, vast course of Roman history, there may have been several shifts in the slave supply; we are focusing on just one possible shift, between the period of Roman expansion, c. 300–1 BCE, and the period of stability following it, 1 BCE–200 CE. And, indeed, smaller ups and downs within each of these periods are quite possible.

The traditional theory does not primarily rest on direct evidence about the slave population. It is mainly an inference from the military history of Rome and the growth in the number of slaves. Roman armies fought often and intensely even before the beginning of the First Punic War in 264 BCE, and Italy’s slave population may have been, very roughly, 300,000 already in 220 BCE. Rome continued to fight many wars in the second and first century BCE, and its empire grew immensely. The slave population of Roman Italy had perhaps grown to about 1.5 million by the reign of Augustus, about 25 percent of a total population of 5.7 million (De Ligt 2012, 72 (accepting Scheidel), 190, 341–342). The temple of Janus provides a memorable symbol of Rome’s almost constant warfare during these centuries. The Romans closed the doors of this temple whenever they were at peace – after winning all their wars of course. Augustus states in his autobiographical Res Gestae that before his reign the Senate had closed the doors only two times in the whole long history of the city (Augustus, Res Gestae 13). This story dramatizes a key fact: the Roman Republic was almost always at war and often on two or three fronts at once.

Critics of the traditional picture of a switch in the main source of slaves can point to successful and large wars during the first two centuries CE, but nothing as constant and intense as the wars by which Rome obtained its vast empire. So the objection that the Pax Romana, the Roman Peace under the early Empire, was not that peaceful does not really get to the heart of the matter. There was in fact a contrast in the intensity of warfare between the last three centuries BCE and the first two centuries CE. The traditional view is not vulnerable to critique in the intensity-of-warfare column.

The primary difficulty in confirming the rest of the traditional theory is the almost complete lack of quantitative information about made and born slaves at any point in Roman history. We find evidence in both periods of the import of slaves, of their capture in war, and of slave families with children. None of this gives us much information about the proportion of slaves coming from one source or another. Some historians have detected a greater concern with slave families in Columella (writing around 50 CE) than in the two earlier agricultural writers, Cato (234–149 BCE) and Varro (116–27 BCE). Might this difference reflect the greater difficulty of importing slaves in the later period and a consequent emphasis on breeding? It may, but most historians are reluctant to put too much weight on this difference: you can’t infer a trend from three authors, separated by two hundred years. For all we know, slave breeding was an individual and eccentric interest of Columella.

The lack of quantitative evidence leaves us in a quandary. On the one hand, nobody ever claimed that the source of slaves went from 100 percent war to 100 percent reproduction. So finding counter-examples will never be decisive. On the other hand, historians would like a statistical answer, for example, 30 percent of the slaves in 100 BCE were born in slavery while in 100 CE 80 percent were born in slavery. Historians can derive such statistics about New World slave societies, and they provide crucial information about the working of slavery. But our evidence about the Roman Republic and Empire is primarily anecdotal. It is compatible both with the traditional picture or its opposite. So it may seem that we are left with a likely enough reconstruction, based on the prevalence of war and growth of slavery during the Republic, but without any way to confirm the argument.

Recently, however, some historians have attempted to solve this impasse by drawing on the discipline of historical demography, the quantitative study of human populations. It may seem mysterious or even improbable that any quantitative methodology can solve an issue about which we lack numerical evidence, since no equation or calculation can produce results that are better than the data we plug into it. Historical demography, however, allows the construction of models of the gains and losses of the Roman slave population based in part on the size of the population and the probable life expectancy of slaves. Even granting large errors in the data used to construct these models, their main result is simple and persuasive: as a slave population grows large – as in the Roman Empire – its resupply will necessarily become more and more dependent on reproduction, a finding in agreement with the traditional model. Just as important for our purposes, simply constructing and thinking about a model of the gains and losses of the slave population involves learning a great deal about Roman slavery.

First, a detour to familiarize ourselves with demography before attacking the problem of the Roman slave supply. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, humanity in general (and especially developed countries) underwent a demographic revolution. People started living much longer and consequently did not need to have as many children to maintain the population. Before this revolution, life expectancy at birth was often only 25 years; some of this was due to infant and childhood mortality, but even a person who made it to twenty could only expect to live to fifty – as opposed to eighty in many places today. In societies before the demographic revolution, that is, high mortality/high fertility societies, populations would stagnate if adult women had fewer than five live births on average, or about six births in total.

Demographers do not have direct access to the mortality, birth rate, or life expectancy of the Roman Empire, but they present good evidence from other societies from before the demographic revolution and are thus able to make a number of probable – if rough – inferences about the Roman population. The life expectancy of a Roman at birth was almost certainly between twenty and thirty years. Some historical parallels suggest that slaves – and the poor in general – die younger on average than slaveholders due to differences in nutrition and living conditions. This is not, however, certain. For example, living in cities was extremely unhealthy due to contagious diseases and poor sanitation, and the Roman elite lived in cities. An aristocrat in Rome may even have had a greater risk of dying than did his slaves out on farms in the country. In any case, we can safely assume a life expectancy under thirty for the slave population in the Roman Empire. The payoff of this reasonable assumption is the following: if we can determine the size of the Roman slave population and assume that it is not changing rapidly, then we can calculate how many slaves were needed each year to maintain its size. We can then consider how much of a contribution different sources of slaves might make to this.

A Slave Population Equation

The ancient social historian Walter Scheidel has explored these issues in several important articles (1997, 2005a, 2011). He believes that neither exposure nor import (via war or otherwise) from outside the Empire came close to matching the contribution that natural reproduction made to the maintenance of the slave population during the Empire, our second period. We can best understand this claim by constructing an equation to describe the Roman slave population. This does not mean that we are introducing any difficult math but it will just help us organize our thinking. Nor does the use of an equation imply any degree of precision. In fact, many of the numbers we use will be ballpark estimates. Nevertheless, stating our results in equation form allows us to see more accurately which scenarios are plausible or not.

Scheidel first assumes that the number of slaves was more or less a constant during our second period since we would hear about a dramatic decline in slave numbers. This assumption is liable to minor objections around the edges: a very slow change in the number of slaves might go unnoticed but still make a difference over the course of a century. Nevertheless, such a slow process would only involve a tiny change each year so the assumption of a constant number of slaves is good enough for our rough purposes and allows us to start our equation: the total loss of slaves each year must be balanced by a gain of about the same number, the annual Roman slave supply. This assumption allows us to approach the size of the Roman slave supply by considering the number of people who left the slave population each year and had to be replaced:

Total Loss of Slaves (per year) ≈ Roman Slave Supply (per year)

The most common way for people to leave the slave population was for them to die, but some slaves escaped and others gained their freedom when they were manumitted:

Manumissions (per year) + Escapes (per year) + Deaths (per year) ≈ Total Loss of Slaves (per year)

The number of manumissions, escapes, and deaths per year all depend on the total number of slaves. Consequently, before we can explore how much the slave population lost in these three ways, we need at least a rough estimate of the total number of slaves in the Empire. The best we can do for this is a very rough figure: about 10 percent of the Empire’s 60 million inhabitants were slaves. Slaves may have constituted more than 20 percent of the population in the center of the empire, Roman Italy, and wherever the use of slaves in agriculture became common. In other places agriculture continued to be dominated by different grades of peasants, sharecroppers, or seasonal hired labor rather than slaves. In those areas, slavery may have been mainly an urban phenomenon and concentrated in the households of the affluent: there the proportion of slaves may have been well below 10 percent. For example, some of our best data comes from census returns preserved on papyrus in Egypt. We would not expect to find large numbers of slaves there, since the agricultural economy remained primarily based on peasant labor. Nevertheless, slaves – probably domestic slaves – constituted slightly more than 10 percent of the approximately 1100 people listed. These returns over-represent cities and towns, where the rich with their domestic slaves would concentrate, so the actual proportion of slaves in Egypt as a whole is more likely to be between 5 percent and 10 percent. On the whole, we’ll be in the right ballpark and keep the math simple if we assume six million slaves, 10 percent (Scheidel 2011, 288–292).

Manumission: As we shall see in Chapter 8, the Romans manumitted large numbers of their slaves. Impressionistic evidence – for example the epitaphs left by ex-slaves in Rome – suggests that some groups of skilled, urban slaves regularly gained their freedom before they died. We now reap the first payoff from demography: despite the tens of thousands of ex-slave epitaphs, not that high a proportion of slaves can have been freed. Scheidel shows that a high rate of manumission would make the replacement of the slave population almost impossible; particularly costly in this respect is the manumission of women still able to bear children, for their subsequent children would be free and would not contribute to maintaining the slave population. Scheidel’s intermediate model of manumission assumes that 10 percent of all slaves gained their freedom at 25 and 10 percent more at five-year intervals. In this simplified model one-third of all slaves would have been freed before they died. Scheidel eventually concludes that even this rate of manumission is too high; the slave population would have declined if so many slaves were freed. We’ll want to keep these percentages in mind not only here, but also when we discuss manumission in Chapter 8: it is fascinating and important that the Romans gave freedom and citizenship to some of their slaves, but we should not forget that a large majority of slaves died while still in slavery. Even with low rates of manumission, more than 30,000 new slaves would have been required each year to replace those who gained their freedom.

Slaves who escaped: The number of slaves who escaped and remained free is impossible to estimate. Most scholars of the Roman slave supply have not even made the attempt, but we know that masters were concerned with the possibility of slaves running away. Such slaves hit them in the pocketbook and, as we’ll explore in Chapter 9, slaveholders took all sorts of counter-measures to prevent flight or to recapture slaves who had run away. But, although fugitive slaves are well attested, their numbers are difficult even to estimate. A couple of historical parallels may also help us here: during the American Civil War, around 10 percent of slaves in Virginia escaped – and freedom was assured in the North during these years. Closer in time, one of Alexander’s finance chiefs, Antimenes of Rhodes, made money from a scheme to insure the masters of slaves in an army camp against the risk of their slaves running away. The annual premium was only eight drachmas, perhaps 4 percent of an average slave’s value, suggesting a low annual rate of escape ([Aristotle], Oeconomica II 1352b33–1353a4). If, at Rome, only one slave out of two hundred escaped each year, which is quite conceivable, that would still add up to a total of 30,000 slaves that needed to be replaced each year.

Deaths: Demography plays a direct role here. The total number of slave deaths per year is a function of the mortality rate and the population of slaves. If the life expectancy at birth of the six million slaves in the Roman Empire was 25 years, about 300,000 would die each year. Once we have added the number of slaves who were manumitted (at a low rate of manumission) and who escaped, we end up with an annual loss of slaves on the order of 350,000 – I round to the nearest 50,000 to make clear that these are very rough approximations.

Now we need to consider how the Romans might have replaced such a large number of slaves every year. The Roman slave supply can be divided into the enslavement of previously free people and the birth of slaves to a slave mother, natural reproduction. The enslavement of previously free people can be subdivided into the following main categories: enslavements in war, by pirates and other kidnappers, via self-sale, and of children exposed at birth:

Roman Slave Supply ≈ Natural Reproduction + War + Piracy + Self-Sale + Exposure

Although there is vigorous debate about almost every aspect of the Roman slave supply and we’ll never end up with precise numbers to put into our equation, considering each possible source of slaves in turn is revealing about how the system of slavery was maintained.

Natural Reproduction: Some Roman slaves had families and children – a topic we’ll explore in Chapter 7 – but the question here is how many on average? W. V. Harris argues that the Roman system of slavery was harsh and that most slaves were males with little chance of a family life. For example, agricultural writers advised slaveholders to give a wife as a reward to the most important slaves on their farms, such as the vilicus, who managed the whole farm.4 This implies that having a wife was a special and rare reward. This makes the most sense if the ratio of male to female slaves was high. On this issue, Harris points to data from the epitaphs in several Roman noble households – including one belonging to a woman, whom we would expect to have more female slaves. These epitaphs suggest that men may have constituted 60–70 percent of the slaves in these households (Treggiari 1975b, 395; cf. Mouritsen 2013, 51). Farms, on which most jobs seem to have been for men, ought to have employed an even greater proportion of male slaves. The fertility rate of a population depends on the proportion of females of childbearing age, so a population containing a majority of males would have little chance of maintaining its numbers, which is not easy anyway when the life expectancy is under 30. Harris argues that Roman slavery was similar to Caribbean slavery, which depended throughout its history on a large proportion of imported slaves from Africa, in part because the population was predominantly male – though the brutal work regime of growing and refining sugar didn’t help either. This would not mean that there was no natural reproduction among Roman slaves, but only that a large and continuous influx of new slaves was necessary.

Scheidel proposes, in contrast, that the Roman slave population mainly reproduced itself. He counters the evidence from epitaphs at Rome and jobs by arguing that women were simply less likely to be commemorated. This was merely part of the neglect of women by the men of a patriarchal society. In a similar way, in the free population women and men were probably present in approximately even numbers, but in all our sources of evidence we find more men than women. So, this argument runs, women were there in equal numbers with the men, but are just not as conspicuous in our surviving, biased sources. Another scholar, Ulrike Roth, argues that even large farms provide another case of this phenomenon (2007). Contrary to the impression we get from our authors who concentrate on fieldwork and its supervision, female slaves were present in roughly equal numbers to the male slaves. They produced clothing for the market (especially for the Roman army), prepared food (an important and time-consuming task in ancient conditions), and raised children.

In general, Scheidel does not believe that Roman slavery was so harsh that masters would not accommodate their slaves who wanted to have and raise children, since these activities were in their financial interest – except perhaps when war captives came on the market in such numbers that buying a slave was cheaper than raising a child. When it comes to historical comparisons, Scheidel believes that the Roman slave population in the imperial period was, in this respect, more similar to the slave population in the United States South. This population had a natural, balanced sex ratio. It not only maintained its numbers but grew considerably during the fifty odd years between the end of the slave trade and the abolition of slavery during the American Civil War.

The issue of the gender ratio among Roman slaves and thus the fertility of the slave population is hard to decide, but Scheidel has another, strong argument up his sleeve, this one deriving from simple math. The number of slaves born in slavery is a function of the size of the slave population; the more slaves, the more slave children. A population of six million can reproduce itself as easily as a population of one million. External sources of slaves are not a function of the size of the slave population; they do not grow in proportion with the number of slaves. Thus the larger the slave population, the more likely it is that natural reproduction will contribute to maintaining it. In the Roman case, Scheidel does not believe that outside sources could produce, year in and year out, anything like the number of slaves required to maintain the slave population of the Empire. Thus natural reproduction must be the main source of slaves. To evaluate this argument let’s return then to the ways that free people became slaves, external sources of slaves, and try to quantify them.

War: During the Republic, the ravaging of Epirus by a Roman army reportedly involved the capture of 150,000 slaves, but this and other mass enslavements are reported because they were exceptional events, not something that happened every year – especially after the reign of Augustus. But for the Roman slave population to maintain itself, 350,000 new slaves were needed every single year.

As we saw in the case of Athens, warfare can produce slaves that then are sold far away to parties uninvolved in the war. Wars outside the frontiers of the empire produced slaves that were then sold across the frontiers to the Romans. We sometimes hear as much, and we can also assume that slaves were imported into the Roman Empire whose enslavement occurred in wars that we do not hear about, for example, raids and counter-raids among German tribes a few hundred miles away from the Roman frontier. Scheidel, however, does have a demographic argument against such wars providing enough slaves to maintain a non-reproducing population. After calculating the highest possible population in the areas around the Roman Empire from which slaves might be imported, he concludes that this population was not large enough to maintain itself if, say, a hundred thousand of its people were every year being imported as slaves into the Roman Empire. This argument is not incontestable – perhaps the population of the frontier zones did decline – but it nevertheless adds weight to the strong general impression that war could not resupply the whole Roman Empire with slaves.

Piracy: During the period of the late Republic, pirates were a major threat to the security of the Mediterranean and a notorious source of slaves. Some pirates once even held the young Julius Caesar for ransom. He promised to come back and have them executed once he was ransomed, and he was good to his word. At another point, the famous general Pompey had to be given a special commission with extraordinary powers and large forces to clear the Mediterranean of pirates, who were threatening the grain supply of Rome. Pompey’s commission was only one of several such appointments to deal with different groups of pirates. But during the Empire, although smaller-scale brigandage and kidnapping continued to plague some areas, piracy largely dried up as a major source of slaves. Instead of the confused, divided, and violent Mediterranean of the late Republic, by the time of Augustus, Rome had made the sea into a “Roman lake” and had every incentive to keep it safe for commerce.

Self-sale: In legal theory, no free Roman citizen could be enslaved within the Roman Empire, but people might wish to become slaves to escape abject poverty and starvation. Accordingly legal loopholes allowed for the transition from freedom to slavery. Most scholars play this down as a source of slaves, but Harris points out that Romans often refer to their own provinces as the source of slaves; it may be that more enslavement than we think was voluntary – at least in the limited sense that a person facing starvation can be said to make a choice. We also hear about men selling themselves into slavery in order to become business agents for rich Romans (Aubert 1994). There were legal advantages to having a slave as one’s business manager, but such self-sales cannot have been significant numerically. Only a few thousand Romans can have been rich enough to need a business agent.

Exposure: As we saw earlier, ancient Romans might “expose” a newborn child if they did not want to raise it. The approximate number of such exposed infants and the proportion raised as slaves is hard to determine. On the one hand, Harris is able to point to several cities such as Paris, Milan, and Moscow with extraordinarily high rates of child abandonment, over 20 percent of births in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. On the other hand, Scheidel calculates that for exposure to contribute significantly to a slave population of six million, it would have to have been common – and not just among the poor. He argues that we ought to have much more evidence of such exposure if it were such a standard practice – and likely a traumatic one.

This all may seem frustratingly indecisive and, in some ways, it is. Nevertheless, two results of the recent, demographic arguments are hard to contest and are important. First, the number of slaves required to maintain the Empire’s slave population is so large that natural reproduction probably played a dominant role. Scheidel believes that it must have provided more than half of the 350,000 slaves needed each year and he favors a higher proportion; Harris is more pessimistic about the birth rate in slavery and favors a higher estimate of the capacity of wars, self-sale, and especially exposure to provide large numbers of new slaves. Even if Harris is correct and the slave population did not come close to reproducing itself, natural reproduction probably constituted more than half of the requisite slave supply and was likely the most important source of slaves by a large margin. Second, once the Empire had grown to its full size, the slave population was so large that not even the most intense warfare on and beyond its borders could provide enough slaves by itself.

Conclusion

Surprisingly, this new thinking about the Roman slave supply reinforces the old view of a shift from war to reproduction as the main source of slaves. Let’s focus on the ratio between the size of the Roman slave population, upon which natural reproduction depends, and the population affected by Roman wars and expansion, the main external source of slaves. During most of the Republic, Roman rule comprised a smaller area and its slave population was smaller whereas the conquest of the Mediterranean basin, France, and Spain led, directly and indirectly, to more enslavement than did later wars under the Empire. (And, as we’ll see next chapter, the wealth pouring into Italy enabled the Romans to import even more slaves.) To take one example, Caesar’s conquest of Gaul in the 50s BCE may have involved the enslavement of one million people over the course of a decade. This would have provided the lion’s share of all the slaves needed to maintain the slave population for those ten years. In contrast, the conquest of Dacia by Trajan after 100 CE was one of the most successful and large-scale conquests under the Empire, but it involved a smaller area and population. And, even if the scale of enslavement was the same as Caesar's – a hundred thousand slaves per year during the four years of the Dacian war – that would have still provided less than a third of the slaves required to maintain the slave population of six million under the Empire.

In the Empire, there was a much larger slave population with fewer wars to maintain it, and these wars drew on a reservoir of potential slaves that was no larger than during the Republic and may have been smaller. Natural reproduction has the unique quality of increasing with the size of the slave population and was thus likely to become more and more important as the Empire and its slave population grew. This tendency, however, was a constant and would not lead to distinct periods, as in the traditional model, but a continuous increase in the proportion of born slaves as the size of the Empire gradually increased over the generations.

Suggested Reading

Follett 2011 provides a concise treatment of the demography of New World slavery. Written from a Marxist perspective, Garlan 1999 is an excellent entrée into the problem of the source of Greek slaves. Rosivach 1999 argues for a very high percentage of foreign slaves; Wrenhaven 2013 and Braund and Tsetskhladze 1989, 119–121, emphasize the difficulty of our evidence. The sources of Roman slaves can be traced in the debate between Harris (1980, 1999) and Scheidel (1997, 2005a). Scheidel 2011 provides a summary of the whole issue with bibliography.