4

Economics

The work done by slaves, though it appears to cost only their maintenance, is in the end the dearest [most expensive] of any. A person who can acquire no property can have no other interest than to eat as much, and to labour as little as possible.

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1937, originally 1776), 365

Introduction

We turn now from the supply of slaves to the demand for them. Societies do not buy slaves in large numbers simply because they accept slavery and a supply of slaves is available. For slaves to be used on a large scale, it usually has to make economic sense to import and exploit them.

Some historians and more classicists, however, have a visceral dislike of economics. Economics works with a simplified conception of human interactions and decisions that can seem improbably distant from how people actually behave and think. According to one witticism, economics describes the behavior of calculating “econs,” not people. Economics thus seems to neglect the complexity and nuance that many historians aspire to in their understanding of the past. It is, however, these reductionist features of economics that give it its great explanatory power. Economics allows insight by reducing the actual complexity of a situation: for example, it tries first to understand human actions in terms of the simplifying assumption that people are rational calculators, who try to “maximize their utility.” This model, of course, underrates the complexity of human motivations, but it allows economists to explain many actions and tendencies. For example, although we do not live in a world of perfect markets today – and ancient markets were even less perfect – the law of supply and demand does explain a great deal about many transactions. We simply need to remember not to confuse a simplifying model with a full explanation of the real world. Economics has proven invaluable for understanding many trends throughout history, including the growth of slavery in both the ancient and modern worlds.

The economics of slavery may also seem inhumane and callous. First of all, in this chapter we will frequently be interested in the question of why rich Greeks and Romans tended to employ slaves rather than other types of workers. This requires us to take the point of view of the exploiter of labor rather than the worker, who, we can assume, does not want to be a slave or exploited at all. In other words, when in this chapter we ask what “you” would do, “you” is usually going to be a slaveholder or a potential slaveholder. Second, we will be talking about concepts like labor, resources, incentives, and efficiency, but all this may seem distant from the experiences of individual slaves and masters. These abstractions are, nevertheless, necessary to understand the institution of slavery and to make some sort of sense of the multitude of individual decisions that brought it into existence and maintained it.

We shall begin by exploring the concept of the slave society and some general theories about the efficiency of slave labor. The main part of the chapter will focus on attempts to explain in economic terms the use of slaves in different periods of classical antiquity. We’ll finish with a more concrete topic: the slave trade.

Slave Societies

Historians categorize only a few states as slave societies. There have been slaves in all sorts of places and times beyond the simplest hunter-gatherers, but in many cases the role of such slaves was to enhance the status and lifestyle of their masters rather than to do productive work. In slave societies, the institution of slavery not only permeates the culture but also the economy.

Until the industrial revolution, the dominant sector of the economy was agriculture: the vast majority of people worked on the land. For example, Roman Italy displayed a high degree of urbanization for a pre-industrial society, but that means that perhaps only 70 percent of the population lived in the countryside instead of 90 percent or more, as in many other societies (Jongman 2003, 103). Although we’ll talk in terms of the whole economy – and slaves were often important in mines and craft production – the organization of agricultural labor will be a key issue throughout the following discussions.

How can we tell if slaves played an important economic role? On the most obvious level, when slaves made up a large proportion of the population, they were almost certain to play a key part in the economy. Slaves can serve as luxuries and status symbols, but you can’t have too large a percentage of the population that is not productive. So, since slaves constituted more than 80 percent of the population on some Caribbean islands such as Antigua and about a third of the population in the antebellum South, these were manifestly slave societies. Like the definition of slaves in terms of property, the definition of a slave society in terms of the number of slaves may not be the most sophisticated approach, but it will rarely lead you astray.

But even estimating the number of slaves in an ancient society can be difficult. Fortunately, there are other and perhaps more illuminating ways to define a slave society, for example, in terms of slavery’s role in the economy. In The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World, the Marxist historian G. E. M. de Ste. Croix argues that when we characterize the labor system of a given period, what is most important is how work is organized beyond the family unit (Ste. Croix 1983, 133). Labor beyond the family may be organized in a non-hierarchical way, but it is much more frequent to have bosses and workers in one form or another. In Marxist terms, the organization of labor is thus the way the ruling class “extracts surplus” from an oppressed class. The expression “surplus” indicates that workers, say on an ancient farm, need to produce more than they consume in order to maintain the lifestyle of a ruling class, who do not themselves plant and harvest food. When a state’s elite predominantly “extracts surplus” from slaves on their farms – or mines or workshops – that state was a slave society.

This definition can diverge from one based simply on the role of slaves in the economy. In some periods and places in Greek and Roman history, independent farmers did most of the farming with their families. In those periods and places much of the economy did not involve the large-scale organization of labor, but, if the elite used slave labor on their large farms rather than exploiting peasants or serfs, then de Ste. Croix categorizes it as a slave society. In theory, one might thus have a slave society without many slaves. In practice, the elite typically control a large enough portion of the economy so that, if they primarily use slaves, that society contains a significant proportion of slaves, and there is no difficulty in calling it a slave society.

When we come to particular ancient societies, the situation is complicated and hard to discern. Often we hear of more than one way of organizing labor: for example, some rich Romans worked their land with tenant farmers while others used slaves – not to mention that some tenant farmers had slaves of their own. Which system was more common? Our scattered and ambiguous evidence often makes it impossible to tell. As a result, the role of slaves in the ancient economy in different times and places is often a matter of controversy. Nevertheless, a short summary will reveal significant and generally accepted differences between periods.

Of the classical Greek city-states, we know the most about Athens. There the rich employed slaves rather than peasants or serfs: for example, Xenophon’s Oeconomicus, which provides guidelines and advice to a wealthy farm owner, assumes a workforce of slaves without any discussion of alternatives. Even middle-class farmers had one or two slaves to work for them. In the cities, workshops – making swords or sofas, for example – were staffed largely with slaves. And the lucrative silver mines depended on a large workforce composed predominantly of slaves. So by the Marxist definition, Athens was a slave society. This impression is in line with estimates that slaves made up more than a quarter of the population of Attica. Other city-states such as Corinth and Corcyra seem to have resembled Athens in their dependence on slaves for labor. But in some other areas of Greece, such as Sparta and Thessaly, we find that nobles exploited peasants or serfs rather than owning slaves.

In the Hellenistic period, slavery continued in mainland Greece and may even have increased with the concentration of wealth and emigration of the free that most historians believe characterized the age. The Graeco-Macedonian ruling class in the Hellenistic kingdoms continued using slaves in their households – as we’ll see in the section called Running Away in Chapter 9. The land, however, was worked mainly by peasants, just as it was before Alexander made his conquests. So most areas of the Hellenistic world were not slave societies.

The conquests under the Roman Republic involved large-scale enslavement as well as growing concentrations of land and wealth. The Roman elite was fabulously wealthy and their households in Rome could include a few hundred slaves. Slaves were just as important in urban crafts and shops. Some ancient sources claim that large farms worked by slaves began to dominate the countryside in many parts of Italy, a controversial topic we’ll revisit later in this chapter. Archaeologists find plentiful evidence for small and mid-sized farms, even after large slave-worked estates had purportedly displaced the peasantry. Yet works of advice for large farm owners once again mainly assume a workforce made of slaves, and a wide array of evidence, including the magnitude of the slave revolt under Spartacus, strongly suggests large numbers of slaves in the countryside. On balance, Roman Italy in the first centuries BCE and CE is usually considered a slave society both in terms of the proportion of slaves and the role they played in the elite’s agricultural labor force.

Whether we should classify the whole Roman Empire as a slave society is less obvious. On the one hand, some areas seem to have experienced the same growth of slave-based agriculture as Roman Italy. On the other hand, traditional systems of exploiting the peasantry remained in place in other areas. In Roman Egypt, as we mentioned above, slaves may have constituted less than one tenth of the population and seem to have been concentrated in the households of the wealthy, while peasants worked the land. This may have been a more typical pattern than the slave plantations of Italy. The eventual decline of ancient slavery is a tricky topic that we shall revisit in Chapter 13.

In sum, in at least two separate (and important) periods of classical history, slaves dominated labor when it was organized in groups larger than the family. Such slave societies are rare, so one can hardly avoid the question: why did classical Greece and Rome become slave societies? Given that the role of slaves in the economy is central to the definition of a slave society, it makes sense to look for an economic answer to this question.

Economics of Slavery

On the one hand, slaves are a capital expense rather than a recurring one like wages: you need to invest a lot of money up front to buy a slave. This is risky, especially in a high mortality society. For this reason, in the American South as well as ancient Rome, slaveholders sometimes hired free men to do particularly dangerous work (Varro, On Agriculture 1.17). On the other hand, slaves sometimes have children and, as we have seen, slave populations sometimes maintain their numbers. In such cases, an initial investment can produce labor indefinitely. Another strategy was for masters to allow slaves to save up monetary rewards to buy their freedom, a practice that recouped the slaveholder’s initial investment and also provided incentives for the slave to work hard – a practice we’ll revisit in Chapter 8.

The economics of slavery seem extremely favorable in other ways as well. You don’t have to pay slaves at all. You need only to feed and clothe them, and you don’t need to do that beyond what will keep them alive and healthy enough to work. You can forget about employee-of-the-month programs or holiday bonuses to motivate your workers; you can whip anybody who doesn’t seem to be working hard enough or threaten to sell their family far away or themselves to the mills or mines. Despite these (cruel) economic advantages, Adam Smith, the founder of economic theory, took the opposite view of the economics of slavery in the quotation with which this chapter began. His line of thought is that slaves are unmotivated – indeed hostile – workers who bring little profit to their master. He also implies a contrast between slaves and wage laborers, who are assumed to have incentives to work hard – an idealized picture in many cases. So we have two diametrically opposed positions: slaves are cheap and can be motivated by violence and threats; and slaves may be cheap sometimes, but they cannot be motivated and are thus unprofitable.

As often, the truth lies somewhere between the two extremes, but we don’t need to settle for an undifferentiated middle ground on this issue. Stephano Fenoaltea, an Italian economist, had an important insight into the adaptability of slavery to different types of work (1984). His basic argument was that “pain incentives,” such as whipping, were sufficient to motivate workers in low-skill activities, such as some types of farming, mining, and construction. In high-skill activities, however, the anxiety caused by the threat of pain inhibits performance and, more important, slaves often have a greater ability to retaliate through sabotage: you don’t want to entrust the care of your prize horse to a disgruntled groom or to really infuriate a slave jeweler to whom you need to entrust gold, silver, and gems. According to Fenoaltea, slavery works only in areas of the economy where pain incentives are effective: there slaves will work hard even if their masters provide no more than subsistence. If slaves are employed in high-skill occupations, the system of slavery will have to depend on rewards including eventual manumission. As a result, so he argues, it will not be a stable system.

Although this picture is generally true of New World slavery, where most slaves performed agricultural labor and slaveholders were diabolically clever about how to apply pain incentives to increase efficiency, Fenoaltea’s theory does not seem to fit the reality of classical slavery well at all. Slaves were conspicuous in skilled crafts and may well have dominated them in some periods and places. Although manumission was practiced in both Greece and Rome, especially in urban contexts, it is hard to argue that urban, skilled slavery was unstable in the classical world. It is well attested from archaic Greece through the late Roman Empire, a span of about a thousand years.

Although Fenoaltea’s theory was originally designed to explain the use of slaves versus free labor, when applied to the ancient world, it ends up telling us more about how masters motivated slaves: with greater reliance on threats where the work was simple and with more reliance on rewards when the work was complex and highly skilled (Scheidel 2008). For example, rewards for skilled slaves often included the promise of manumission, which is not disruptive under two conditions: the society had an inexpensive supply of new slaves; and there were no strong ideological barriers to allowing slaves to gain their freedom. In many periods, Greece and Rome satisfied these conditions, but the antebellum South did not. There, racism and the threat of abolitionism made it hard to allow too many blacks to gain their freedom, and the slave trade had been shut down by the early nineteenth century. Thus, classical slave societies had the flexibility to use slaves in both low- and high-skill jobs, whereas in the antebellum South the vast majority of the slave population was employed in low-skill agricultural work and motivated by pain incentives. Even this is, of course, more of a rule of thumb than an unbreakable law. For example, some slaves in the South did skilled work and were motivated to do it well, mainly by rewards (e.g., Dew 1994, 108–121).

To explain the growth of slavery in certain periods and places in the classical world, Scheidel goes back to a basic model historians use to understand the economics of New World slavery: imported slaves become valuable, and the institution of slavery may become central when a society has an abundance of resources, usually land, and too few available workers. At that point, the import of labor becomes attractive to those who own land that they are not able to work otherwise.

Outside the modern period, this type of situation is not, however, that common. In the absence of technological advances, the population of pre-industrial societies often grew to or above the number that the land could support – as the pessimistic demographer Thomas Malthus posited in An Essay on the Principles of Population in the late eighteenth century. A state in such a Malthusian condition would never pay to import large numbers of slaves, who would simply represent more mouths to feed. Throughout history, many elites depended on the exploitation of peasants to maintain their lifestyle. Such peasants reproduced themselves, had few rights, and paid their surplus production to those higher up the social hierarchy, either through taxes, rents, sharecropping, labor obligations, or some related system. Peasants often required less supervision than chattel slaves typically do. Such societies had no economic incentive for the extra, imported labor that slaves provided – though this does not rule out a few slaves in specific niches or as part of the lifestyle of the elite.

In the New World, however, slavery was employed on a grand scale and, economically speaking, it is not hard to see why. Europeans through conquest and disease quickly gained access to huge amounts of land on which they could produce cash crops: sugar, tobacco, and cotton. The supply of free labor to work this land was eventually insufficient. In addition, the very availability of land made free labor less practical:

The story is frequently told of the great English capitalist, Mr. Peel, who took £50,000 and three hundred laborers with him to the Swan River colony in Australia. His plan was that his labourers would work for him, as in the old country. Arrived in Australia, however, where land was plentiful – too plentiful – the laborers preferred to work for themselves as small proprietors, rather than under the capitalist for wages. (Williams 1964, 5)

Basically, the laborers decided they would rather have their own farms, since land was readily available, than work for Mr. Peel. So the Mr. Peels of the world often turn to coerced labor in situations where land is plentiful or some other factor makes wage labor hard to obtain. Slavery is one alternative, though it was convict labor that played a large role in the early settlement of Australia.

These inquiries into the economic prerequisites for the widespread use of slaves have revealed three main points. First, there must be a supply of slaves available at lower cost than the supply of free labor. To put it more simply, slaves must be readily available and free labor not. Second, there must be new resources, usually land, that require more labor in the first place. This usually occurs in times of rapid change or even turmoil; otherwise labor and resources tend to be more or less balanced. Third, the easy availability of land or some other factor may by itself make coerced labor more profitable than paying wages.

We will consider two case studies in the economics of slavery in light of these factors. We’ll first consider the Roman Republic, where the spread of slavery was based not only on conquest, but also on economics. Then, we’ll consider the evidence that slaves were cheap relative to free labor in classical Athens but not during the high Roman Empire.

Roman Expansion

At first glance, the massive influx of slaves into Italy during the mid- and late-Roman Republic seems not to have had an economic basis at all. Roman armies were fighting almost constantly and large numbers of people were enslaved in these campaigns. It may seem that the Romans did not buy slaves in order to make a profit with them; rather, slaves were part of the profit they obtained from successful warfare.

Furthermore, rich Romans employed slaves in large numbers to enhance their status or to provide luxury services. You couldn’t play the part of the big man in Rome without a large and conspicuous crowd of slaves escorting you wherever you went. Some Roman aristocrats even dressed their slave escorts in fancy matching uniforms. Slaves who were obviously expensive, rare, or exotic – for example, African slaves or matched twins as litter-bearers – also contributed to making a grand and elegant impression. As for luxuries, the lists of slave jobs in great Roman households included masseuse, nomenclator (to memorize names and announce guests), and a specialist in setting pearls; whole teams of slaves were assigned to take care of their owner’s wardrobes or to help the mistresses of the house do their hair and make-up (Treggiari 1975a, 51–57). Such slaves represented, so the argument runs, a way to spend money rather than to make it. There is something to be said for this view: Roman slavery in the Republic was more directly connected with conquest and war than New World slave systems; Roman slaves often served prestige and luxury functions.

Economics is still in the picture, since slaves were also a profitable investment. Striking confirmation for this picture comes from inscriptions at Delphi in Greece that commemorate the manumission of slaves during the period of the late Republic. These often give the price that a slave paid for his or her freedom. The sociologist and ancient historian Keith Hopkins considers these prices a proxy for a slave’s market price; his basic and admittedly rough assumption is that most of the time a slave owner would want to be able to buy a replacement for the slave he or she was freeing. During the late Republic, the prices slaves paid for their manumission increased significantly.1 But it was during this period that Rome was fighting constant and intense wars and making major conquests all around the Mediterranean basin. Why would the price of slaves be going up when we might have expected the market to be glutted with them?

The most parsimonious explanation of this increase in price is that Roman conquest involved the acquisition of other forms of wealth even more than of slaves. The Roman elite acquired money with which to buy slaves, and it was worth their while to do so even as slave prices rose. Slaves were not just for luxury and display. Rather, Roman aristocrats acquired huge tracts of land as the result of conquest, and slaves provided much of the labor on the farms and ranches they established on this land. We know this from various sources, but especially from the three books on farm management that have survived from ancient Rome. These agricultural dissertations are all addressed to absentee owners whose farms were worked primarily by slaves. Even the overseer, left in charge of running the farm, was a slave, and his main task was the effective management of the other slaves working the farm. In addition, these authors repeatedly make it clear that their goal was to maximize profitability.

None of this is surprising. Roman nobles often reaped great wealth from conquest and empire, either directly or indirectly; it would have been strange indeed if they had spent all of it on show and luxury. They also invested their wealth and expected a return on their investments. The safest and most prestigious way to invest it was to buy land – especially Italian land on which no taxes were levied – and the most lucrative way to work that land was with slaves. This brings us to the key issue in the economics of ancient slavery: why was slave labor in this period more profitable for landowners than some other system of labor such as sharecropping or some other way of exploiting native peasant labor?

Hopkins provides an explanation in his classic book Conquerors and Slaves. He first outlines the striking difference between the clear economic rationale of New World slavery and the situation in Roman Italy:

When we compare Roman with American slavery the growth of slavery in Roman Italy seems surprising. In the eighteenth century, slavery was used as a means of recruiting labour to cultivate newly discovered lands for which there was no adequate local labour force. Slaves by and large grew crops for sale in markets, which were bolstered by the incipient industrial revolution. In Roman Italy (and to a much smaller extent in classical Athens), slaves were recruited to cultivate land that was already being cultivated by citizen peasants. We have to explain not only the import of slaves but the extrusion of citizens. (Hopkins 1978a, 9)

Then Hopkins sets out to explain how the two factors crucial to New World slavery – empty land and markets for produce – were also present in the Roman case.

In the New World, plentiful land resulted from the extirpation of native populations through war and disease. Why was land available for Roman nobles to buy up and to farm with foreign slaves? The answer comes in several parts. For starters, the Romans often confiscated territory from the states they defeated in war. This “public farmland” could be farmed by any Roman, but the rich tended to move in and take possession. In fact Roman nobles often exceeded the statutory limit of 500 jugera – 300 acres or 125 hectares – which was rarely enforced by the Roman state, dominated by the very men who were most likely to break the rule. This land was like the “empty land” in the New World, which also came from the displacement of prior owners.

More benign processes also played a part: in many rural societies, some peasants fall into debt every generation and are eventually forced to sell their holdings. Bad weather, for example, can easily ruin a farmer whose crops for the year are destroyed. This is true especially if the disaster comes at a bad time in the family life-cycle; for example, a farm is particularly vulnerable when a farming couple has had several children, and thus more mouths to feed and to care for, but the children are not yet old enough to work. All sorts of other possible problems can be imagined and no doubt occurred.

Roman small farmers were even more prone to losing their land than peasants in most states because of the extraordinary military demands of the Roman state. As we have already seen, for a period of a couple of centuries Rome regularly mobilized many of its men for military service. Hopkins makes some reasonable assumptions about the length of military service and the life expectancy of Roman males and concludes that perhaps 80 percent of all Roman men served five years in the army during their life; more recent treatments suggest a less extreme, but still high, military participation rate.2 Depending on when military service took place, a farm could easily be lost when labor was insufficient. For instance, it could be advantageous for a younger son to go away and make some money in the army. But, if an only son was absent overseas for a few years and his father died, the widow might struggle to hang onto the farm.

That Roman nobles wanted to invest their money in land could make the decision for a small farmer to sell a struggling farm easier: land was valuable. In addition, other ways to make a living were possible and often attractive due to Rome’s imperialism and the wealth it brought to Italy. Nevertheless, the elite’s thirst for land to work with slaves occasionally meant that violence and threats were used to force peasants from their land. Although land was not sitting around, plentiful and deserted for their use, one way or another, the Roman elite found plenty of land to work with their slaves. And this seems to have been a profitable proposition.

This profitability brings us to the issue of markets, of how a farm worked by slaves would function efficiently within the larger economy. Most obviously, such farms only make sense if there is a market for agricultural produce. In primitive economies, agricultural production aims mainly at growing grain for subsistence. This obviously would not provide the basis for a profitable investment: Roman nobles didn’t want to buy slaves and land in order to eat a lot of bread! Their farms could only make a profit if there was somebody to whom they could sell their surplus. If such farms were to be a large part of the economy, there had to be a large market for agricultural produce. Such a market presupposes an economy that, if not modern, is at least a long way from being primitive. Hopkins argues that this was the case in Roman Italy. As the result of Rome’s conquests and wealth, the cities of Italy grew and the proportion of the population living in them rose to a level probably not equaled in Europe until the eighteenth century. Rome in particular may have had a population of one million, a level that London only matched around 1800 (Jongman 2003, 100; Hanson 2016). These urban dwellers provided a large market for agricultural produce; this tendency was increased when the state instituted a grain dole for citizens at Rome, thus subsidizing the urban market out of the profits of empire. The Roman army added to the demand for produce and clothing. These markets made the transformation to large slave-worked farms profitable.

Slave labor was most efficient for certain crops; the production of grain, the staple food of the Roman world, was not usually one of them. Grain cultivation has extremely uneven labor demands. There are a few periods of intense work, most obviously the harvest time. Much less labor is required during the rest of the year, but slaves would still need to be fed. So, if you were the owner of a grain farm, slaves would not be an obvious choice for your workforce. Some slave-worked farms in Italy may have produced grain at a profit nonetheless, but slave labor was most suited for mixed agriculture and cash crops such as olives and wine. Farms with such products are able more efficiently to use slave workers, since the labor demands for orchards and vineyards, for example, are spread out over the year. This effect is amplified if a farmer has several different crops with offset seasonal labor demands. Then the expense of maintaining slaves over the whole year makes financial sense: they can work all year. The historian Ulrike Roth suggests that the production of clothing, on which women could work throughout the year, may also have been a lucrative activity on these estates (2007, 53–118).

So far this is all somewhat hypothetical. It makes sense that rich Romans, trying to invest their imperial wealth profitably, would buy land and work it with slaves to produce cash crops for the market. Hopkins also provides a plausible explanation in the urbanization of Italy, a phenomenon confirmed archaeologically, and the large Roman army for why markets existed for the varied cash crops produced by these farms. But did large farms with slave labor actually displace peasants? Yes, at least according to the martyred reformer, Tiberius Gracchus, in the late second century BCE. The Greek biographer Plutarch describes how Gracchus got the idea that Rome needed agrarian reform:

When Tiberius on his way to Numantia passed through Etruria and found the country almost depopulated and its husbandmen and shepherds imported barbarian slaves, he first conceived the policy that was to be the source of countless ills to himself and to his brother. (Plutarch, Tiberius Gracchus 8, trans. Jongman 2003, 110)

In a similar vein, the historian Appian describes the situation as follows:

The rich took possession of most public land . . . and acquired nearby, smaller farms either by purchase and persuasion or by brute force. They ended up with huge tracts of land instead of single farms. To work these lands they bought slaves as farmhands and shepherds, since free men could be drafted into the army and taken away. (Appian, Civil War 1.7, trans. White 1913)

These accounts seem to confirm Hopkins’ basic model, but they show an obvious moralistic and political slant and derive from Greek authors – albeit well informed ones – of the late first and second century CE. Depicting the displacement of the sturdy Roman peasantry by foreign slaves was part of a general condemnation of the Roman elite for their excessive greed, which according to these authors led to the civil wars and eventually the fall of the Republic. But, though these reports are biased, are they wrong? More specifically, is there any material evidence that could bear on this issue?

In the Italian countryside, archaeologists have excavated large houses from the Republic and early Empire, often referred to as villas. These sites are consistent with the picture painted by ancient authors of extensive estates with a workforce consisting of slaves. Some even contain rooms with shackles in which recalcitrant or suspect slaves might be chained at night or for punishment; others contained cramped little rooms where slaves perhaps slept. The interpretation of these villas is, unfortunately, controversial (Joshel and Petersen 2014, 162–213). They show a great deal of variety in construction, and some are more likely just country or “summer” homes for Rome’s elite rather than working farms – not that these categories are mutually exclusive. The existence of large houses in the countryside is consistent with the theory that large farms worked by slaves displaced small farms owned by free peasants; it does not prove that theory.

In contrast to these excavations of specific sites, archaeological surveys – which confine themselves to what is on the top of the soil but cover a much larger area of the countryside than an excavation – reveal ancient field patterns and the location and numbers of ancient farms and villas, all crucial evidence for understanding the organization of the Roman countryside. The results of surveys in Italy are different than we would expect based on the accounts of Plutarch and Appian. First of all, habitation patterns varied from area to area within Italy. Second and most important, a recent synthesis of 27 archaeological surveys indicates that the number of villas was growing over time but that smaller farmsteads were also becoming more common. Some of these farmers may have owned a few slaves, and many may have been tenant farmers of the villa owners (Launaro 2011, 158–162). Still most historians think that the supposed destruction of the Italian peasantry has been exaggerated. The displacement of some peasants by slave-worked estates was balanced – or more than balanced – by all the advantages that come with being at the center of a great imperial power. Rather than just a story of impoverished peasants and the desertion of the countryside, the prosperity of many free Italian farmers and the opportunities available to them may even have raised the cost of free labor and made slave labor more attractive to the rich (De Ligt 2012, 154–157) – similar to the dynamic in Athens we’ll explore below. Although some small farmers may have moved to cities, the free population of Italy as a whole probably declined only slightly even while slaves were being imported in great numbers.

Scholars have also questioned the theory that Italian agriculture moved away from grain production towards the market crops, such as wine, which were more amenable to slave labor. Based on calculations of agricultural productivity per hectare, the social historian Willem Jongman argues that a large shift away from grain to vineyards, for example, could not have occurred: “It would have left Italy both fatally hungry, and dangerously drunk” (Jongman 2003, 111). Neither the displacement of smallholders nor the switch to market crops was as extensive as Hopkins originally envisioned. A dramatic switch to slave labor is harder to picture absent these trends. Accordingly, historians’ estimates of the Italian slave population have come down from three million or two million (by Hopkins) to under one million. I prefer an intermediate estimate of Roman Italy’s slave population: 1.5 million by the reign of Augustus, about 25 percent of a total population of around 5.7 million (De Ligt 2012, 190, 341–342).

Despite these revisions, the overall contours of Hopkins’ model won’t be replaced anytime soon. The main parts of the puzzle – wars, a growing slave population, the displacement of some peasants, and the agricultural use of slaves – are all well documented. Hopkins’ model puts them all together in a way that makes both historical and economic sense. We do need, however, to admit that the displacement of peasants by slave plantations was not as prevalent as Hopkins thought and that there were many other things going on, not all of them detrimental to the free population of Italy.

The Cost of Labor in Athens and the Roman Empire

We do not have good information about the prices of slaves in Italy during the Republic, but Scheidel contrasts the real cost of slaves and of free labor in classical Greece and under the Empire in the first three centuries CE to explain the greater proportion of slaves in the former case.3 In order to compare costs in such different periods and places, he expresses the price of slaves and of free labor in terms of grain, a proxy for cost of living. Using this basis of comparison, Scheidel shows that free labor cost at least twice as much in classical Athens as in the Roman Empire and that slaves were less than half as expensive in Athens. Given that economic background, the higher reliance on slave labor in Athens is easy to understand.

Scheidel’s data varies greatly in quality and type. On the Greek side, there are prices for slaves on the Attic Stelai and for wage labor on inscriptions recording the expenditures for various construction projects in and near to Athens. On the Roman side, he finds references to slave prices in legal texts. More important are papyri from Roman Egypt that record both wages and slave prices. Scheidel also collects references to prices or wages wherever they appear in Greek or Roman texts of whatever genre: law-court speeches, plays, or philosophical works. Although one could argue that one or another of these numbers was unrepresentative – and Scheidel does depend a lot on data from Roman Egypt – his data is coherent and allows the kind of rough estimate that he is looking for. Most decisive, the difference he finds between the prices of free and slave labor in Athens and in the Roman Empire is too great to be a figment of poor data.

These results support a simple economic explanation for the expansion or decline of slavery in the absence of moral compunction: where slave labor is inexpensive relative to free labor, we find that slave labor was used more.4 Thus, slavery was more common in classical Athens than in the Roman Empire. Some historians estimate that the slave population of Athens could have been as high as 150,000, roughly a third of the population; even low estimates have slaves making up 20 percent of the population. As we saw in the last chapter, most historians think that slaves constituted about 10 percent of the population of the Roman Empire. So, the relative prices of wage labor and of slaves are consistent with the fact that slave labor was more common in classical Athens than during the Roman Empire. But why were slaves cheap and free labor expensive in one society and not in the other?

First, the supply of slaves. As a major port, Athens imported slaves from the whole Greek world and beyond. The presence of peasant/serf labor systems in some other parts of the Greek world like Thessaly, Messenia, and Laconia meant that there was little demand for slaves in those areas, which may have depressed the price of slaves. More important, ancient Greece included colonies throughout the Aegean and Black Sea and the wider Mediterranean. As we have seen, these Greek cities were often on the coasts of lands inhabited by non-Greeks in sporadically hostile relations with the colonies. Thus the ratio of borderland – marked by wars and slave raiding – to the size of Greece and to its population was high. In contrast, Rome was a huge empire with a large population; its borders were distant and had largely stabilized by the imperial period. They were longer than the borders of the Greek world but not to the same degree that Rome’s area and population was larger.

The high cost of free labor at Athens was largely a consequence of its democracy. First off, the legal rights of poor citizens were assured to such an extent that rich litigants occasionally complained that they were treated unfairly in court. This was probably an exaggeration, but even the equal legal protection of the poor and rich is rare and remarkable. A large jury of ordinary citizens would have the final say in the case of a disagreement between an Athenian free worker and his employer, and the laws gave every male citizen equal rights – as the Athenians loved to boast. In Roman Egypt, such a dispute would be decided by a magistrate who was of the same class as the employer and who probably despised the poor Egyptian laborers, whose very language he might not understand. We do not have to imagine that such legal cases were very common to understand that the Athenian worker and the laborer in Roman Egypt were in different bargaining positions vis-à-vis their employers and that this contributed to a difference in real wages.

Scheidel emphasizes a second factor contributing to the high cost of free labor at Athens: the existence of other demands on the time and energy of the citizens. In Athens, citizens had many opportunities to take part in politics, something many considered important to a full life. In addition, they were required to serve in the military. These institutions made the supply of labor other than slaves smaller and less dependable. The most common competition with slave labor in the ancient world was not free wage labor but rather other sorts of un-free labor such as serfs or bound peasants. But early in the history of Athens’ democratic development, the Athenians had eliminated debt bondage and given peasants full title to their land, where previously they were sharecroppers. So these other ways of obtaining labor were not available to wealthy Athenians.

Some scholars also invoke the unwillingness of free Athenians to work for another individual for a salary on the grounds that this was somehow slavish. Several ancient sources equate working for another person with slavery and even specify that the wages paid were the proof of a person’s slavery. If this attitude actually influenced people’s willingness to take wage labor – and it must have had some effect – it would have diminished the labor pool and made the cost of wage labor greater. The problem is that this attitude could just as easily have been a result of the reliance on slave labor rather than its cause. The hesitation to perform work for others may have stemmed from the fact that many of those who worked for others were indeed slaves. So we can’t really tell whether this was an independent factor driving the use of slave labor or a circumstance that, once the slave system was in place, tended to ensure that it stayed.

One can argue about how much weight to put on different explanatory factors for the labor and slave supply in classical Athens and the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, Scheidel’s data on real slave prices strongly suggest that the extent of slave use, in the ancient as well as the modern world, was largely a matter of economics.

The Slave Trade and Slave Traders

One modern statistician, waxing poetical in defense of his field, described social statistics as “frozen tears.” The preceding discussions may indeed have seemed abstract and cold, but there are plenty of tears there too. Our last topic is the slave trade, an aspect of the economics of slavery that was brutal, but at least brings us back to the concrete experiences of the men, women, and children who suffered under slavery. The slave trade was not only a significant and profitable sector of the ancient economy, but it also shows us in primary colors the terrible effects of slavery on its victims.

The economic impact of slavery included not only all the economic roles slaves filled – in agriculture, crafts, and mining, for example – but also all the people employed, and the money to be made, in acquiring and transporting slaves. Although the overall scale of the slave trade, both the numbers and distances involved, was greater in the Roman than the Greek world, many common features do not require separate treatment. Throughout antiquity, slaves were being moved from one place to another, often in large numbers, to accommodate differences in demand and the vagaries of the supply of slaves. For example, we know that slaves were often sold in war zones for much less than their value in the heartland of Greece or of Rome. Although Trajan’s column depicts newly captured slaves locked in holding pens as part of the glorification of his Dacian campaigns (ca. 114 CE), commanders usually did not want to have to guard slaves for extended periods. Occasionally, slaves were distributed among the soldiers. More regularly, merchants followed armies around for the chance to pick up enslaved people at cheap prices and then to transport them, often by foot, to places where they could be sold at a profit.

An important general consideration comes into play here: slaves became increasingly powerless as they were separated from their homelands and people. Tens of thousands of Epiriots in Roman stockades on the outskirts of Epirus after the mass enslavements there in 167 BCE were in a grim position, but they knew that, if they could escape and elude capture, they might have a chance to resume their lives once the Roman army left. They knew the countryside and could both communicate and cooperate with each other. They might even resort to violence if not carefully guarded or chained. Imagine those same tens of thousands, but now scattered on farms throughout Italy, isolated or in small groups among other slaves from other places, in the land of their enemy with no easy way home, and among a population in the millions controlled by the Romans, whose language they could not speak. They would be much more easy to manage and thus more valuable to their owners. In general, new slaves’ vulnerability and thus their usefulness went up the further from home they were. This is not just a classical phenomenon: pre-historians and anthropologists observe that slaves were often among the first objects of long-distance trade for this reason (Patterson 1982, 148–149).

In the classical world, the life of slavery often began with a lot of walking. Slaves captured in Britain, in the campaigns under Emperor Claudius for example, might start their enslavement with a boat ride across the English Channel and then by walking more than 1000 miles to Rome, often in coffles – groups chained together. Archaeologists occasionally find the actual chains used for this purpose. Chaining seems not to have been a universal precaution, since several stories in The Life of Aesop concern a slave trader traveling with slaves who are not bound (18–19 in Daly 1961). Transport by ship must also have been common around the Mediterranean and the navigable rivers, but no evidence survives of ships specifically designed to transport large numbers of slaves – as were used in the modern Atlantic slave trade.

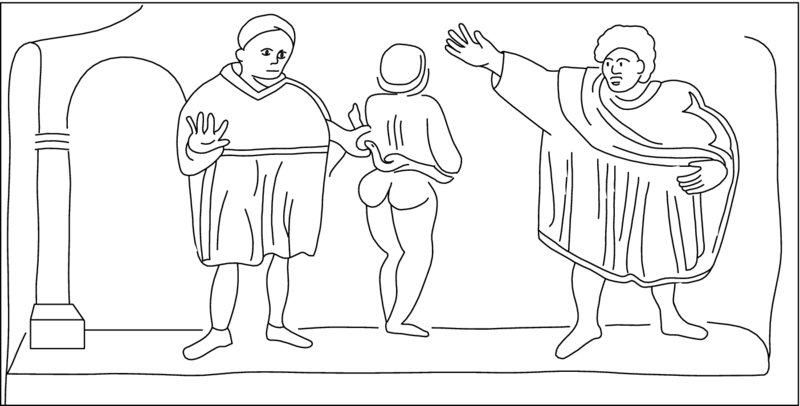

Figure 4.1 Slave auction scene. Ex-slaves who were rich enough owned slaves themselves; some even engaged in the slave trade. This scene on the gravestone of a Roman freedman shows an assistant (left) displaying a slave’s buttocks to customers, while the auctioneer makes a large gesture, whose exact meaning is open to interpretation. Source: After a drawing by A. Wiltheim, seventeenth century, in Waltzing 1904, 300.

Many large cities had markets regularly used for the sale of slaves – whether this was their only use is controversial.5 Some of these markets may have been designed with the control of human merchandise in mind: they seem to be laid out deliberately so that there were only a few narrow exits. Guards could watch these to be sure that no slaves slipped out in the bustling crowds. When they were put up for sale in the market, most slaves were displayed on a platform, where potential buyers could question them or inspect their bodies after having them strip. All of these practices were profoundly dehumanizing to people who had been free and perhaps even noble a short time before. It symbolized the separation of slaves from their past lives that they were often given new names, either by the slave traders themselves or by their new masters. One more-humane Greek practice is attested: newly purchased slaves were marched around their new homes and sprinkled with dried figs and sweetmeats, just as a new bride was, perhaps to symbolize the good things in their new life.6 I doubt that many slaves were convinced.

In contrast, Xenophon tells a story that illustrates the harshness of the slave trade: the Spartan king, Agesilaus, when he moved camp, made sure that the little children abandoned by slave traders were not just left to die (Xenophon, Agesilaus 1.21). Presumably slave traders viewed the children as unprofitable and inconvenient: they could not walk far or fast, would slow and distract their parents, required food, and were not worth much in a world with high child mortality. It was Agesilaus and his army who had enslaved the families in the first place, but he and his admiring biographer Xenophon seem to have seen the inhumanity of leaving children to die of starvation and exposure, something slave traders would sometimes do.

In general, slave traders had a bad reputation. A law-court speech from fourth-century Athens criticizes a certain Timandros for being a terrible guardian to some orphans, whom he separated. To highlight his faults, Hyperides makes two claims about slave traders (Against Timandros in Jones 2008, 19–20):

- Even slave traders don’t separate children from their siblings or mothers (something Timandros purportedly did).

- They do commit all sorts of other crimes for the sake of profit.

The first claim was not generally true in the Greek world, as the Agesilaus story shows. Nor does it hold true in the Roman world, where we find evidence such as a sales receipt for a ten-year-old girl sold by herself in Asia Minor and probably bound for Egypt without any family with her (Papyrus Turner 22 in Bradley 1994, 2). The threat of separation and that slaves sometimes managed to start and maintain families nevertheless are topics we’ll consider in Chapter 7.

The second claim sums up a negative stereotype of slave traders, which seems to be widespread in both the Greek and Roman worlds – as it was in the American South (e.g., Aristophanes, Wealth 521–526; Bodel 2005). Several considerations explain why the reputation of slave dealers was so low in antiquity. First off, their relationship with slaves was purely a mercenary one: they had not captured the slaves themselves, which would at least have demonstrated military prowess; nor were they in a long-term relationship that could be palliated by the ideological veneer of paternalism that sometimes concealed the violence and exploitation in the relationship between master and slaves – see Chapter 11. So, although the elite in Greece and Rome can hardly have disapproved of slave traders on the grounds of their participating in slavery, perhaps the traders displayed slavery in a form more raw than slave owners wished to see.

But the most important factor in the bad repute of slave traders may have been a simple matter of money. The rich landowners, who dominate our sources – as they dominated their societies – had opposing interests to slave dealers: slave dealers wanted to sell slaves for as high a price as possible, whereas the elite wanted to buy slaves for as low a price as possible. Slave dealers often possessed better information than potential buyers about a slave they were trying to sell, and some naturally tried to take advantage of this to sell slaves for more than they were worth. In particular, some sellers concealed problems that made a slave worth less than he or she appeared. Others tried to make slaves look younger, more attractive, or healthier than they really were – using ingredients typical of ancient medicine such as resin from the terebinth tree or the root of hyacinth.7 Roman legal texts are particularly concerned with these issues and specify a host of “defects” that slave traders must openly declare or else the sale of a slave could be declared invalid. These included latent physical problems, but also whether a slave had ever tried to commit suicide or had a tendency to “wander” (Bradley 1994, 51–55).

We can’t tell whether slave traders were actually more dishonest than other merchants, but one result of this negative stereotype was that we know the names of extremely few slave traders from antiquity. Although we have thousands of epitaphs from the Roman Empire declaring the deceased’s profession, few proclaim that the deceased was a “slave trader” – and this despite the fact that many people must have made a living in the slave trade. One exception is the gravestone of Aulus Kapreilius Timotheus, a seven-foot-high and well-made marble headstone, which declares Aulus’ profession as “slave trader” and includes among other images a depiction of a coffle of eight male slaves walking along chained together at the neck with two women and two children unchained behind them (George 2011, 392; Finley 1977). It is noteworthy that Aulus was himself an ex-slave – that ex-slaves often owned slaves is a phenomenon we’ll explore in Chapter 8. Successful ex-slaves did not necessarily share the sensibilities of those born to wealth, and so Aulus may not have realized the social stigma attached to his profession – or he may have just decided to ignore it. In literary sources, it is only the spectacularly gauche Trimalchio, a freedman character in Petronius, who is unembarrassed about trading in slaves (Petronius, Satyricon 76) – and that was on the grand scale.

For new slaves the experience of being captured, marched for long distances across the countryside, or shipped across the Mediterranean must have been horrific. To have one’s body poked and inspected at a public market – considered a particularly shameful part of slavery in our sources – and to be sold who knows where to who knows whom must have been terrifying. But just as slaves in the New World made lifetime bonds with other slaves from the same ship from Africa – known as malungo in Brazil (Hawthorne 2010, 132) – so too we read the following on the epitaph of a Roman ex-slave, commemorated by his friend:

To his fellow freedman and his dearest companion. I do not remember, my most virtuous fellow freedman, that there was ever any quarrel between you and me. By this epitaph, I call on the gods above and the gods below as witnesses that I met you in the slave market, that we were made free men together in the same household, and that nothing ever separated us except the day of your death. (CIL 6.22355A, trans. in Joshel 2010, 109)

Conclusion

It would be misleading to end this chapter on such a positive note. The big and grim picture is clearly that economic forces, unrestrained by moral compunctions about slavery, led both classical Athens and Roman Italy (at least) to exploit slave labor to such an extent that they belong to the small group of slave societies known to human history. The elite in other periods of classical antiquity also possessed slaves with as few qualms, but it was the economic advantages of slave labor that made its use prevalent in those two places and times.

Suggested Reading

Scheidel 2008 provides an overall theory of economic factors that favor slavery and applies it to Greek and Roman slavery. Hopkins 1978a is the classic explanation of how slaves displaced subsistence peasants in Italy during the late Republic. Jongman 2003 criticizes several of Hopkins’s main arguments. Analyses of the extent to which large, slave-worked farms did in fact displace free Italian peasants have to take into account the interpretation of ancient census data as well as survey archaeology, estimates of urban populations, and comparative history – all tricky and controversial topics. No fewer than three recent books treat this topic in detail: Launaro 2011, De Ligt 2012, and Hin 2013 – with Scheidel 2013. Finley 1977 uses the gravestone of Aulus Kapreilius Timotheus, described above, as an entrée into a discussion of slave traders in antiquity. Braund 2011 and Bodel 2005 provide more recent overviews of, respectively, the Greek and Roman slave trades.