I: |

MATHEMATICS, |

That mathematics is one of the oldest and richest of the disciplines is generally conceded. What is not so commonly understood is that mathematics is also one of the most rapidly expanding of the disciplines. Several times in the life of a mathematician he can expect to be asked, “But what do you do? Is there anything new to do in mathematics?” Scientists and engineers are less subject to this sort of question, for everyone knows that these men are plunging ahead to marvelous new discoveries in their fields. But there is a widespread feeling that mathematics is a precise but static body of knowledge that was pretty well roughed out by the Greeks and other early peoples, leaving little for modern man to do but polish and refine.

Nevertheless, a mathematician finds it much easier to describe what he does than to answer the question “What is mathematics?” Attempts to define mathematics range from pithy sentences to books in multiple volumes. It has been variously described as a language, a method, a state of mind, a body of abstract relations, and so on. A thoroughly satisfactory definition is not easily attained.

In describing what he does, a mathematician is likely to list creation of new mathematics as one of his important activities. Creation of new mathematics involves first discovering new mathematical relationships and then proving them. In searching for new mathematics, the mathematician does not limit his methods. He uses his imagination and ingenuity to the utmost. He experiments and he guesses. He uses analogies. He may build machines and physical models. He makes some use of deductive methods but much more use of inductive methods. In the heat of the search nothing is illegal.

Once he has guessed a new relationship and has satisfied his intuitions that the new idea is reasonable, the mathematician has what he calls a conjecture. He next tries to change the conjecture into a theorem by proving (or disproving) that the conjecture follows logically from the assumptions and proved theorems of known mathematics. In constructing a proof, he sharply limits himself to the methods of deductive logic. He does not allow his proof to depend on experiment, intuition, or analogy. He tries to present an argument satisfying a set of rules that mathematicians have agreed such arguments must satisfy.

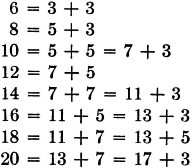

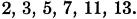

A very famous conjecture of mathematics is due to Goldbach (1690–1764), who conjectured that every even integer greater than 4 is the sum of two odd prime numbers.1 We do not know how Goldbach was led to this discovery, or just how he satisfied himself as to its reasonableness, but a reasonable way to test the conjecture would be to test some particular cases:

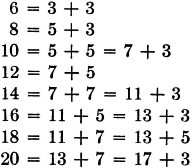

The first few cases work out nicely. To increase one’s confidence in the conjecture, one might try some larger numbers chosen at random:

The more special cases one verifies, the more confidence one has in the conjecture, but of course no amount of verified cases constitutes a proof. No one has published a proof of this conjecture to date; neither has anyone found an even number greater than 4 and shown that it is not the sum of two odd primes. Thus the truth of Goldbach’s conjecture remains an open question.

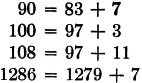

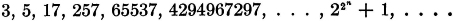

Another well-known conjecture concerns the sequence:

The mathematician Fermat [1601(?)-1665] made the conjecture that all the terms in this sequence are prime numbers. It is not too hard to verify the conjecture for the first five terms of the sequence, corresponding to n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4. To verify that 257 is prime, for instance, it is only necessary to show that it is not divisible by any of

One can determine if any integer N is prime by testing to see if it is divisible by any lesser prime. In fact, one easily sees that it is sufficient to test for divisibility by the primes that are not greater than the square root of N. In the case of the fifth term 65537, one would then test the primes less than 256. Since there are 54 of these, the task will be tedious. To determine, by this method, whether the sixth term 4294967297 is prime would require testing each of the primes less than 65536 to see if any one of them divides 4294967297 exactly. Since there are 6543 primes less than 65536, one would not look forward to the task. In fact, mathematicians will not engage in such computations as this if they can possibly avoid them, particularly since it is clear that the computations become much worse for later terms of the sequence.

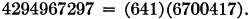

There is evidence that Fermat felt quite strongly that his conjecture was reasonable; yet the mathematician Euler (1707–1783) found that the huge number can be factored as follows:

This remarkable discovery settled Fermat’s conjecture once and for all. The terms of the sequence are not all primes. Further study of this sequence has led to other conjectures and theorems of considerable interest, but we cannot pursue the matter here.

Having seen an example of an open conjecture and of a disproved conjecture, one naturally looks for the discussion to be rounded out with an example of a proved conjecture. But almost any theorem of mathematics is an example, for nearly all theorems were conjectured before they were proved. It is generally a reasonable conjecture that provides one with a motive, and the courage, to attempt the arduous task of forging a proof. Imagine being asked to prove a relationship between the hypotenuse and legs of right triangles if you have never heard of the Theorem of Pythagoras!

The mathematician usually presents his results as a series of theorems with proofs. This method of presentation tends to obscure the thought processes which led to his conjectures, as well as the methods he used to discover his proofs, but it has the advantages of precision and economy of exposition. The requirement that new additions to mathematics be proved exerts a profound unifying effect on the development of the discipline. It ensures that the body of mathematics grows in an orderly way, and that new mathematics is immediately related to existing mathematics. The solid organization of the structure of mathematics makes it possible to leap ahead oftener and further than is possible in some of the new disciplines that do not yet have such well organized structures.

The system of deductive logic provides mathematics with

a. An efficient means of exposition, and

b. An efficient means of organizing its subject matter.1

In what follows, we shall be concerned with this formal, logical side of mathematics. The logic provides a symbolic language with which to talk about mathematics with ease and precision. We shall also have to introduce a symbolic language in order to talk about the logic with ease and precision.

We shall have little to say in this book about the creative, conjectural side of mathematics, but this should not be construed as indicating any judgment about the relative importance of the formal side and the creative side of mathematics. Both sides are essential to the discipline.

1 A prime number is an integer that has no positive integral factors other than itself and one. For various reasons, it is best to exclude 1 from the set of primes, although it meets the requirements of the definition.

1 Of course, logic also provides these means for the sciences and other disciplines which use them in varying degrees and with varying success.

Consider the case of a mathematician who has arrived at a reasonable conjecture. However plausible or seductive the conjecture, he must view it with suspicion until he knows whether it is “true”. We use quotation marks here because in this case “truth” means consistency with the body of accepted mathematical statements. To verify this consistency, the mathematician tries to construct a proof that will show that the statement of the conjecture follows logically from accepted mathematical statements. If he succeeds in this endeavor he considers that he has proved his conjecture, and henceforth has the same attitude toward it as toward any previously accepted mathematical statement. Another mathematician will accept the new statement only if he agrees that the proof is correct, or if he can construct a proof of his own.

It appears that there must be some general agreement among mathematicians as to the meaning of the phrase “follows logically” as used above, and some generally accepted rules for constructing proofs. We shall mean by formal logic just such a system of rules and procedures used to decide whether or not a statement follows from some given set of statements.

Suppose a mathematician has arrived at a conjecture D through introspection, intuition, and verification of particular instances. He feels sure that it is correct. Now he is faced with the necessity of establishing D according to the strict rules of deduction. The mathematician might reason, “I know that A was proved to my satisfaction by Xoxolotsky in 1951. Clearly B follows from A. D is my conjecture and it follows from C. Aha! B implies C, so I know that D follows from A and my conjecture is proved.”

Formal logic will not indicate what sequence of statements to choose for a proof, but once such a sequence of statements is chosen, the logic is designed to decide whether B follows from A, C from B, D from C, and ultimately whether D follows from A. Furthermore, the logic is designed to decide such questions purely on the basis of the forms of the statements involved, without reference to their meanings.

The point of view expressed in the preceding paragraph can be illustrated by familiar examples from Aristotelian logic. Sooner or later in books on logic it is traditional to present an argument about Socrates:

1. All men are mortal.

2. Socrates is a man.

∴ 3. Socrates is mortal.

The Socrates Argument is regarded as an example of a valid form of reasoning in Aristotelian logic; that is, according to the rules of this logic, if any three statements have the forms (1), (2), (3), then (3) follows from (1) and (2). The argument is correct no matter what meanings statements (1), (2), and (3) have; all that is required is that they have the forms of (1), (2), and (3). The three statements in the example would generally be considered true (or perhaps more accurately, at a suitable time in history they were considered true). In any event, to say about the statement “All men are mortal” that it is true is to voice a judgment based on its meaning, and meaning is not in question when we are considering the validity of an argument.

Consider another example of the foregoing valid form of argument:

1. All people who like classical music are baseball players.

2. Babe Ruth liked classical music.

∴ 3. Babe Ruth was a baseball player.

Most people would judge (1) to be false, would agree that (3) is true, and would not feel qualified to judge the truth value of (2). Such judgments about the meanings of the statements do not affect the validity of the argument. If statements (1) and (2) are granted, then we are forced to grant the conclusion (3).

It is easy enough to construct a correct argument in this form whose conclusion is false. For instance:

1. All who ride by airplane were born after A.D. 1800.

2. Socrates rode by airplane.

∴ 3. Socrates was born after A.D. 1800.

The conclusion is a false statement. Yet, although the conclusion is ridiculous, the argument that led to it is valid.

The assertion “Truth is not the concern of logic” is too broad, since we shall want to say of arguments in the above form that if the first two statements are each true, then so is the third statement true. But in this sense, we arbitrarily assign the value “true” to each of the first two statements, and state as a rule of the logic that the third statement must then be assigned the value “true”. The truth of the statements in terms of their meanings is not in question. Of course, we construct a system of logic in order to help us reason with meaningful statements. While it is the goal to develop methods for determining validity that are mechanical and based on form alone, still the valid forms should be such that from hypotheses that are true in the sense of meaning we obtain inescapable conclusions that are true in the sense of meaning.

The form of the Socrates Argument is not determined by the words “men”, “mortal”, “Socrates” but by the other words in the statements and by the order in which the statements occur. If the words “men”, “mortal”, “Socrates” are replaced, respectively, by the terms “person who likes classical music”, “baseball player”, “Babe Ruth”, then we have an argument which is still in the form of the Socrates Argument but whose meaning is the same as that of the second example. (We overlook here some grammatical discrepancies of tense and number.) Since the form of the argument is not dependent on the particular terms used, we are tempted to exhibit the form as

1. All ______ are ______.

2. ______ is ______.

∴ 3. ______ is ______.

However, this pattern is not adequate since it seems to permit six different terms for distribution in the blank spaces, and the two examples deal with only three terms each. We are then led to exhibit the form as

By this scheme of lettering the blanks, our intent is to indicate that whatever the three terms chosen to fill in the blank spaces, those blank spaces designated by the same letter must be filled in with the same term. It will be simpler to indicate a blank space by a letter without any underscoring, thus

1. All M is P.

2. S is M.

∴ 3. S is P.

In Aristotelian logic, an important form of argument called the “syllogism” has forms somewhat similar to that of the Socrates Argument. The statements appearing in syllogistic arguments are simple declarative sentences, usually called propositions, that are classified under four headings:

| Classification | Examples |

A: Universal and affirmative |

All men are mortal. |

E: Universal and negative |

No men are mortal. |

I: Particular and affirmative |

Some men are mortal. |

O: Particular and negative |

Some men are not mortal. |

The logical form of a proposition is:

Subject—a form of the verb to be—predicate.

The terms in the subject and predicate can usually be satisfactorily interpreted as names of classes, and the relation between subject and predicate is taken to express the inclusion of all, part, or none of one class in the other. An example of a syllogism is:

1. All monkeys are tree climbers.

2. All marmosets are monkeys.

∴ 3. All marmosets are tree climbers.

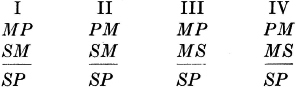

A syllogism is an argument consisting of two propositions called premises and a third proposition called the conclusion. In the premises two terms are each compared with a third, and as a result there is a relationship between the two terms that is expressed in the conclusion. Traditionally, the term in the subject of the conclusion is called “S”, and that in the predicate “P”; the term to which they are both compared is called the middle term, and is denoted by “M”. With this notation, the form of the foregoing syllogism can be expressed:

This syllogistic form is said to be in the first figure, and its mood is “AAA”. The figure is determined by the position of the middle term, and the mood by the kinds of propositions and the order of their occurrence. Since interchanging the order of the premises does not change the relationships they express, it does not matter which is written first. It is traditional to write the premise comparing M and P first. Subject to this tradition, there are just four possible distinct figures:

Since each of the three propositions in a syllogism can have any one of the forms A, E, I, O, each figure can have 43 different moods. Hence, in all there are 256 different forms possible. Most of these forms are not considered to be correct forms of reasoning. In a traditional treatment, a set of rules is given for differentiating between the valid and invalid forms. Four of these rules are:

1. A syllogism having both premises negative is invalid.

2. In a valid syllogism, if one premise is negative, the conclusion is negative.

3. In a valid syllogism, if both premises are affirmative, the conclusion is affirmative.

4. A syllogism having both premises particular is invalid.

There are other such rules. The complete set of rules applied to the 256 possible forms of a syllogism identify 19 valid forms. According to these rules, the remaining 237 forms are classed as invalid.

This very brief excursion into Aristotelian logic serves to illustrate that methods of describing validity are formal and arbitrary. The rules for differentiating between valid and invalid syllogisms can be thought of as axioms of Aristotelian logic, and they are concerned solely with the forms of syllogisms, and not at all with meanings. All the words:

Syllogism |

Negative |

|

Figure |

Premise |

|

Mood |

Conclusion |

|

Affirmative |

etc. |

refer to various aspects of form, and are not concerned with any meanings that may be attached to the propositions in a syllogism. Of course, it is no accident that when we do consider the meanings of the propositions of a VALID syllogism, we find that if the premises are true then so is the conclusion true. For, however formal the system, it was created with just such an interpretation in mind.

In succeeding sections we want to describe a formal logical system suitable for the exposition and organization of modern elementary mathematics. We shall need a precise language for describing this system. It will be a language suitable for describing form, and it will be largely symbolic.

Any book is sure to be full of statements. In this book, statements not only occur but are talked about and relationships between statements are discussed. In this sort of discourse it is well to be careful about the use of names. Names are used in statements to mention objects. Our language is so constructed that a statement about an object never contains that object but must contain a name of that object. Consider the statement

(1.1) This pencil has soft lead.

The expression “this pencil” names an object, and it is this name that is contained in the statement, rather than the object. If one were to take the pencil mentioned in (1.1) and hold up next to it a slip of paper with the words “has soft lead” written on it, he would probably succeed in conveying the sense of (1.1), but he would not be communicating by means of a sentence or statement.

No one dealing with a statement about a physical object is likely to confuse the object with its name. This kind of confusion is more likely to arise when the object mentioned in a statement is itself a name. In the statement

(1.2) Seattle is in the state of Washington,

the name of the city is used to mention it; there is little likelihood of confusing the name (a word) with the object (a city). Now it is reported that the name of the city mentioned in (1.2) is derived from the name of a Duwamish Indian. Suppose we attempt to convey this information by writing

(1.3) Seattle is derived from the name of a Duwamish Indian.

Since it makes no sense to say that a city (a large complex physical object) is derived from the name of an Indian, we conclude that the first word in (1.3) cannot refer to a city, and that (1.3) is supposed to assert something about the name of some city.

The modes of expression in (1.2) and (1.3) are not compatible. The trouble is with (1.3), which violates the conventions regarding use and mention by employing as its first word the object about which (1.3) is supposed to be saying something. If (1.3) is considered to assert something about a city, it is a correctly formed sentence, but false. If (1.3) is considered to assert something about the name of a city, then it is not a sentence for the same reason that a pencil followed by the phrase “has soft lead” is not a sentence. The conventional way to deal with this problem of written exposition is to write

(1.4) “Seattle” is derived from the name of a Duwamish Indian.

The quotation marks are used to indicate that it is the name of the city that is the object of discourse, and not the city itself. For further illustration compare the statements

(1.5) Syracuse is in New York State.

(1.6) “Syracuse” has three syllables.

(1.7) “Syracuse” designates a city on Onondaga Lake.

(1.8) Syracuse is north of Ithaca.

It would be quite wrong to omit the quotation marks in (1.6) and (1.7) since a city cannot have three syllables, nor can it designate anything.

The combination of quotation marks with a word (or words) in their interior is called a quotation. A quotation names, or denotes, its interior, which is always an expression rather than a physical object. Thus it is correct to say

(1.9) “Syracuse” is used in (1.5) to mention Syracuse.

The name-forming device of quotation keeps us straight about what objects are mentioned in (1.9). Since the first expression in (1.9) is a quotation, we know that it is the name of the city that is being mentioned, whereas the last expression in (1.9) clearly mentions the city itself.

In each of (1.2), (1.5), and (1.8) the first expression is a name of a city. In each of (1.6), (1.7), and (1.9) the first expression is a name of a name of a city. Of course, we can carry this further by writing

(1.10) “Syracuse” is used in (1.6) to mention Syracuse.

The first expression in (1.10) is a name of a name of a name of a city. We shall not need to go this far in the succeeding sections. We shall have to mention names, so will use names of names, but we shall not have to mention any names of names, so will not use any names of names of names.

In mathematics and logic, it will not do to confuse objects with their names. In logical discourse one can expect the name-forming device of quotation to be used freely. Mathematical writing is conventionally less careful in this matter, and one often has to determine from context what the objects of discourse are. Generally the context is clear and no confusion of object and name is likely; yet there are some areas of mathematics in which this kind of confusion has occurred and has given rise to furious controversy. One such controversy arises periodically concerning the distinction between zero as a number and as a placeholder. Those who maintain that zero is a number like to cite contexts for zero, such as

to support the notion that zero behaves like other numbers. Supporters of zero as a placeholder like to cite its use in expressing such numbers as 20, 1000, 207, etc. The controversy arises from a confusion of name and object. While one side talks about 0, the other side talks about “0”, and neither is aware that they are talking about different things. The controversy disappears when careful distinction is made between 0 and “0”. Consider the statement

(1.11) The sum of 0 and 3 is 3.

This statement mentions the numbers 0 and 3 by using the symbols “0” and “3”. Now consider the statement

(1.12) 20 can be expressed by “2” followed by “0”.

This statement describes one way that 20 can be expressed by symbols. The symbols are “2” and “0”, which are names of the numbers 2 and 0, respectively. The statement (1.11) mentions the number 0, and (1.12) mentions the name “0”.

The distinction between 0 and “0”, or between 7 and “7”, is just the distinction between a number and a numeral. Numerals are special names for numbers. A given number may be mentioned by using various different numerals. For instance, in the statement

(1.13) 7 is greater than 1,

arabic numerals “7” and “1” are used to mention the numbers 7 and 1. One could as well use the Roman numerals “VII” and “I” to mention 7 and 1; thus

(1.14) VII is greater than I,

or use Greek numerals to write

(1.15) ζ is greater than α.

One might say that the number 7 has no nationality, but the numerals “7”, “VII”, and “ζ” do have nationalities. Statements (1.13), (1.14), and (1.15) are undeniably different, but they both mention the same objects in the same way and have the same meaning.

It is a general principle that one may substitute for a name of some object in a given statement any other name of the same object without altering the meaning of the given statement. It is easy to misuse this principle when applying it to a statement in which objects and names are confused. Consider the following short argument:

1. The denominator of 14/18 is even.

(1.16) 2. 7/9 is another name for 14/18.

∴ 3. The denominator of 7/9 is even.

At first glance, the argument is apparently correct and the first two statements apparently true, but the conclusion seems false, so we seem to have a paradox.

Let us examine each statement in the argument (1.16) to ensure that in each the intended objects are correctly mentioned. In (1) the object apparently mentioned is the denominator of 14/18, but there is no such object; 14/18 is a number and cannot have a numerator or a fraction bar or a denominator. The words “numerator”, “fraction bar”, “denominator” designate parts of symbols used to denote rational numbers. Thus the object that should be mentioned in (1) is “14/18”. Similar remarks apply to statement (3). As for (2), the first expression in it is clearly intended to mention a name of a number, and not a number, so quotation must be used.

Properly rewritten (1.16) becomes

1′. The denominator of “14/18” is even.

(1.17) 2′. “7/9” is another name for 14/18.

∴ 3′. The denominator of “7/9” is even.

Now it begins to become clear why (2′) does not justify the substitution in (10 that yields (3′). The object mentioned in (1′) is the name “14/18”. To make the substitutions, we would need to know some other name for “14/18”, but (2′) just gives us another name for the number 14/18, so (2′) is of no use here. On comparing (1′) and (3′) we see that neither could be obtained from the other by substitution because the objects mentioned are different; hence the names used to mention them are not interchangeable.

The same sort of fallacy is illustrated by the nonmathematical argument

1. “Mark Twain” is a pseudonym.

2. “Samuel Clemens” is another name for Mark Twain.

∴ 3. “Samuel Clemens” is a pseudonym.

The foregoing examples contain several cases of different words or symbols that are names of the same object. Some of these cases are listed below:

Name |

Type of object named |

the first expression in (1.5), “Syracuse” |

a city |

the name of the city mentioned in (1.2), “Seattle” |

a city |

the first expression in (1.6), “‘Syracuse’” |

a name |

“7”, “VII”, “ζ” |

a natural number |

“7/9”, “14/18” |

a rational number |

“Samuel Clemens”, “Mark Twain” |

a person |

A conventional way of expressing

“7” and “VII” are names of the same object

is to write

7 = VII.

Similarly,

7/9 = 14/18

means

“7/9” and “14/18” are names of the same object.

In the same sense we may write

Mark Twain = Samuel Clemens.

We shall take this interpretation of “ = ” in all subsequent exposition. We shall also use the substitution rule that in any statement, one name may be substituted for another as long as both are names of the same object. This interpretation of equality, and the substitution rule, are consistent with mathematical practice.

The conventions regarding use and mention apply when we want to write about statements. In order to mention a given statement we have to use a name of it. The device of quotation is a convenient way of forming the required name. If we want to say of statement (1.5) that it is true, we write

(1.18) “Syracuse is in New York State” is true.

Other examples of statements about statements are

(1.19) In “Syracuse is in New York State” both a city and a state are mentioned.

(1.20) “All women are faithless” is unbelievable.

(1.21) “All cats are black” and “No cat is black” are both false.

(1.22) “‘Syracuse is in New York State’ is true” is believable.

(1.23) “He lies” is blunter than “He prevaricates”.

A way of writing about a statement without using quotation marks is to display the statement centered on the page and on a new line. We have used this device repeatedly; indeed we have just used it six times in this section. Instead of (1.18) we can write

(1.24) Syracuse is in New York State

is true. To center and display material in this fashion is tantamount to quoting it, and permits some reduction in the number of quotation marks needed.

Yet another way to avoid quotation marks is to use the numeral at the left-hand margin as a name for the material displayed on a line with it. Thus (1.18) can now be written

(1.24) is true.

By the same device, the complicated statement (1.22) can be written

“(1.24) is true” is believable;

or even,

(1.18) is believable.

Finally, we shall never use a letter as the name of a statement. When we write

(1.25) A: John is dead,

we intend “A” as a symbolic translation of “John is dead”, just as “Jean est mort” is a French translation of it and “Johann ist tot” is a German translation of it. With this agreement, we can write about the statement (1.25), or the statement “A”, or the statement “John is dead”, and have it understood that we are simply mentioning a single statement in three different ways.

We have dwelt on these devices at some length because they will all be used repeatedly in the subsequent exposition to ensure that it is always clear about what we are talking. It must be confessed that very often omission of quotation marks causes no confusion, and in a good deal of mathematical exposition they are not used. We shall sometimes omit quotation marks in what follows but will try to avoid this practice whenever real confusion might result.

EXERCISES

1. Put quotation marks where necessary in each of the following sentences in order to make them meaningful statements.

a. Chicago has three syllables.

b. The sum of 16 and 0 is 16.

c. In the preceding statement 16 and 0 are used to mention the numbers 16 and 0, respectively.

d. Another way to express 20 is by an X followed by another X.

e. The numerator of 8/13 is even.

f. 2/3 is another name for 6/9.

g. It is 6/9 that has a numerator, fraction bar, and denominator, but 6/9 has none of these.

h. The denominator of 5/9 is odd.

10/18 is another name for 5/9.

∴ The denominator of 10/18 is odd.

2. Indicate the kind of object named by each of the following symbols.

a. F.D.R. Ans. The object named is a former Democratic president.

b. 3

c. “5”

d. A.D.

e. ΔABC

f. Russia

g. “Russia”

3. Write a sentence in which you use correctly:

a. H-bomb

b. “H-bomb”

4. Mention Illinois in a sentence.

5. Use “Illinois” in a sentence.

6. Can you use Illinois in a sentence?

7. Mention a name of New York State in a sentence.

8. Write a true statement about all college students.

9. Write a true statement about “all college students”.

10. Write a true statement about “To be or not to be is the question”.

11. Rewrite those of the following statements that you think need quotation marks. If necessary, support your answer with reasons.

a. Bookkeeper is one of the few words in the English language containing a double k.

b. If 18 is divided by 3, the result is 6.

c. Big Ben has a pleasant sound.

d. Big Ben is alliterative.

e. Angle ABC indicates that B is the vertex of an angle.

f. We use 3, 1, and 5 to write 315.

g. One way to name 47 is to write 4 followed by 7.

h. 5 is used in the direction on page 5 you will find ….

i. ABCD or q can be used as names for a quadrilateral.

12. Restate the meaning of “x = y” in your own words.

13. “ΔABC = ΔDEF” should mean that “ΔABC” and “ΔDEF” are different names for the same triangle. Discuss various interpretations of “ΔABC = ΔDEF” as used in plane geometry.

14. If A and B are points, then “AB” denotes the line segment determined by A and B. This is the customary notation of plane geometry. Yet “AB = CD” is not interpreted as a statement about a single line segment, but as a statement about two different line segments. Discuss this point.