3

The Little Red Plane

In the summer of 1916, Amy, Amelia, and Muriel rejoined Edwin Earhart in Kansas City. He was overjoyed. Edwin wanted to help his family again. For this reason, he talked Mrs. Earhart into going to court to break Grandmother Otis’s will. Mrs. Earhart’s brother, who took care of her money, had lost much of it on bad business deals. The court ruled in Mrs. Earhart’s favor. She used the money to send her daughters to good schools.

In the fall of 1916, Amelia arrived at the Ogontz School in Rydal, Pennsylvania. She was an excellent student and an outstanding athlete. She liked to play hockey, basketball, and tennis. Her letters to her mother were happy and filled with the details of her school activities.

Amelia was tall and slender, and the girls quickly nicknamed her Butterball. They liked her and Amelia liked them. Still, she was not afraid to speak her mind.

During her first year at school, Amelia belonged to a secret club. When she realized that some students had not been invited to join, she asked the members to include the other girls. They refused. Amelia went to the headmistress, who ran the school, and asked that another club be added for these girls. Instead, the headmistress did away with the secret clubs.

On another occasion, Amelia argued that the students should have the freedom to discuss and read anything they wanted. These actions set her apart from the other girls. But, as always, whenever Amelia believed in something, she was willing to “walk alone.”

For Christmas of 1917, Amelia and her mother visited Muriel in Toronto, Canada, where Muriel was at school. One day, as Amelia walked down King Street, she saw something that changed her life. She met four young men using crutches. Each of them was missing a leg.

The young men had been hurt in battle. For three years, there had been war. The Great War, as it was called then, lasted four years. (Almost 25 years later, the Great War was renamed World War I, when World War II began.) The Great War destroyed countries, governments, homes, and lives. Nearly 10 million soldiers were killed. More than 15 million people were wounded.

While at school, Amelia had knitted socks for soldiers. Until she met the soldiers in Toronto, however, she didn’t fully understand the horrors of fighting.

Right then and there, Amelia made a decision. With her mother’s permission, she did not return to school. Instead, she stayed in Toronto and became a nurse’s aide.

She worked from seven in the morning until seven at night, with two hours off in the afternoon. At the hospital, Amelia gave medicine, scrubbed floors, prepared meals, gave back rubs, and wrote letters for soldiers.

When Amelia had spare time, she liked to ride a wild horse named Dynamite. One soldier told her that she rode Dynamite the way he flew his plane. Sometimes the ride was smooth and sometimes it was rough. Amelia stayed on the horse.

Something else caused Amelia to think about planes. One afternoon at an air show in Toronto, Amelia and a friend were watching a pilot doing stunts in the air. Perhaps to tease the girls, the pilot headed for them. Amelia’s friend screamed and ran, but Amelia stood still. She heard the sound of the motor. She felt the wind on her face. She was excited. Years later, she wrote, “I believe that little red airplane said something to me as it swished by.”

When the war was over in 1918, Amelia became ill with pneumonia (say, “new-MOAN-ya”). Muriel had moved to Northampton, Massachusetts. Amelia stayed with her sister and spent nearly a year resting and recovering. She bought an old banjo and learned to read music. Like her father, Amelia played by ear. Once she heard a melody, she could then play it. She also signed up for a five-week course in car repair.

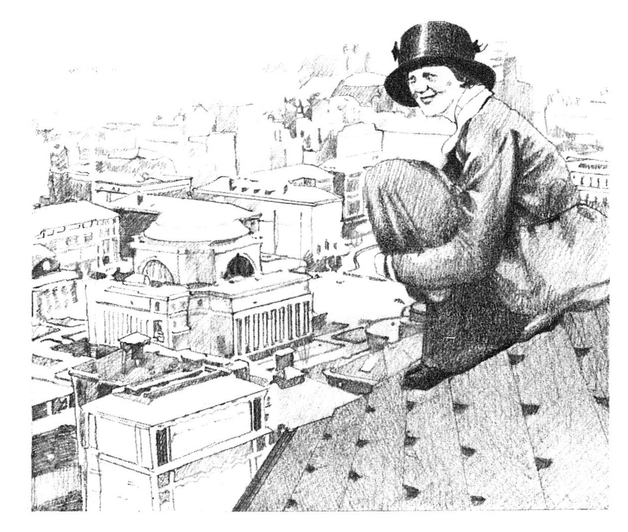

In the fall of 1919, she entered Columbia University in New York City. She wanted to be a doctor. She had always liked science and she did well in her classes. For fun, Amelia took a course in French poetry. And for excitement, she used to sit on top of the Columbia library dome. Somehow, Amelia discovered where the key to the roof was kept. Dressed in her hat and long skirt, she would crawl out onto the roof. There she sat on the sloping roof, hugging her knees and staring at the buildings below her.

By the spring of 1920, Amelia decided she really did not want to study medicine. Her parents had moved to Los Angeles, California, and they asked her to live with them. Even though her father was no longer drinking, they weren’t happy. Amelia wanted to help.

The Earharts lived in a large home and rented out some of the rooms. One of the renters was a young chemical engineer by the name of Sam Chapman. Sam and Amelia spent many hours together. Sam loved Amelia. He asked her to marry him, and for years, he waited for her answer. She always said no.

Sam believed that a wife should stay at home and take care of children. But a marriage like that hadn’t made Amelia’s parents happy. Besides, she insisted, women should have the same freedom as men. More than anything, Amelia wanted to be independent. She wanted a career of her own.

Still, a career in flying was the farthest thing from Amelia’s mind. In World War I, a few thousand pilots took part in the bombing and fighting. But in 1920, stunt flying was about the only thing to do with a plane. For whatever reason, Amelia began attending air shows. Perhaps she remembered the little red plane.

One day, Amelia and her father stood on the sidelines and watched. “Dad, please ask that officer how long it takes to fly,” she said.

Mr. Earhart did. He told his daughter it took five to ten hours to learn.

“Please find out how much lessons cost,” Amelia continued.

“The answer to that is a thousand dollars. But why do you want to know?”

Amelia wasn’t really sure. A few days later, one of the pilots took her up in his plane. From her seat behind the pilot, Amelia saw the ocean. She saw the Hollywood Hills. And suddenly, everything became clear to Amelia. There was only one thing to do. As she wrote later in her book, The Fun of It, “I knew I myself had to fly.”