Chapter 2

FEVER

THE PARENTAL fear that a doctor will probably encounter most often in the office is that of fever. The textbook definition of fever is any temperature of 100.4°F or higher. It is common for moms and dads to anxiously call the office anytime the thermometer reads 101°F or higher.

The good news is that the vast majority of fevers are not dangerous. Fevers can become dangerous when they reach 107.6°F or higher, but this is rarely, if ever, seen in a pediatric office.

On the other hand, fevers spanning 100.4–106°F are seen several times a day in every pediatric office. Fevers in this range will not hurt the brain. Many moms and dads have heard of a fever triggering seizures, and although this can be alarming to the parent, the good news is that simple febrile seizures (a seizure associated with a fever) are not dangerous, and typically have no lasting effects; this is in contrast to other types of seizures, which can be more concerning.

Fevers are a natural and healthy response of the immune system. A solid understanding of what a fever is will help parents not to panic the next time their child gets sick, and may even save them a visit to the doctor.

HOW FEVER IS TRIGGERED

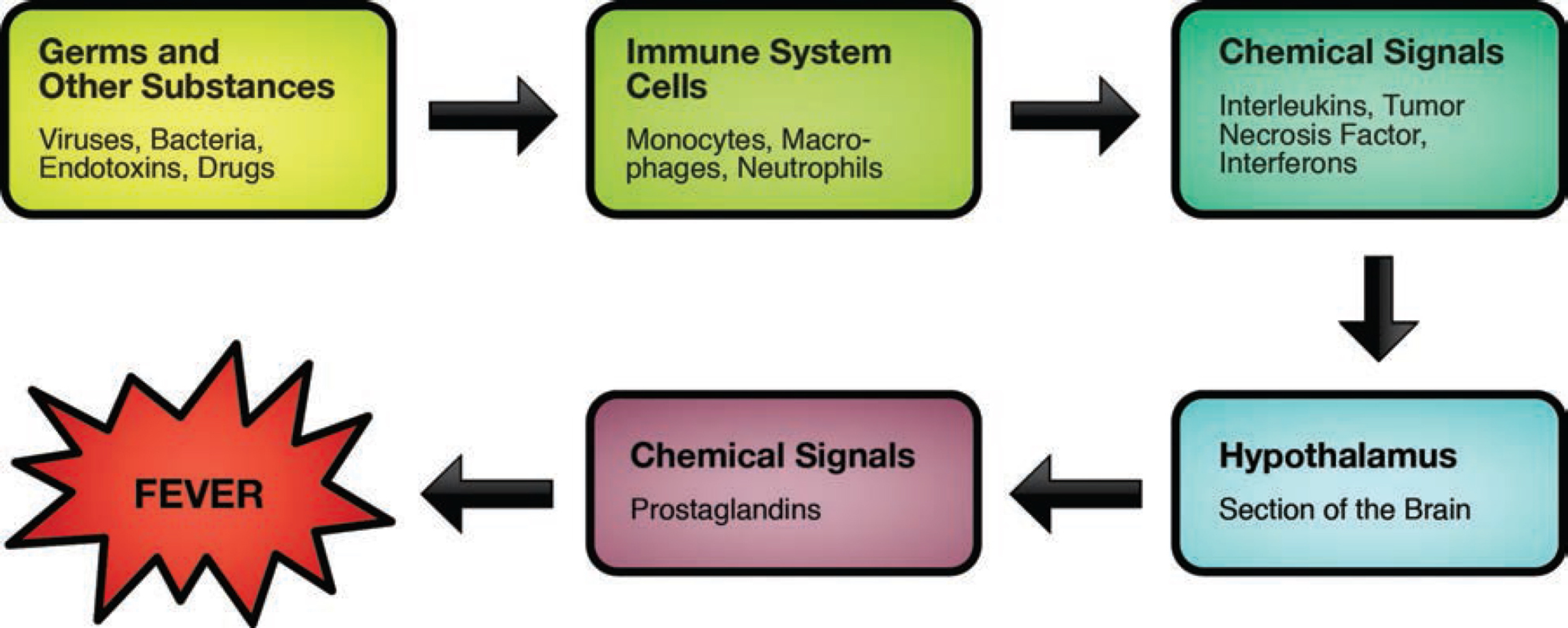

The pathway to fever is an intentional series of chemical signals orchestrated by the brain. Germs (or other foreign substances) entering the body are the typical source of fever. Fever is purposefully created by the body to help our immune system fight a germ more efficiently. In other words, fevers are beneficial in fighting off germs.

If this is true, then should a fever-reducer be used at all?

Great question!

If a child is comfortable and able to drink liquids in order to stay hydrated, it is probably better not to use any type of medication to keep the fever down.

However, an uncomfortable child may refuse liquids, which can lead to dehydration; as such, although the fever is being helpful in fighting off germs, the child who is refusing liquids should be treated with a fever-reducer, as it is more important to keep the child well hydrated.

It is also perfectly reasonable to use fever-reducers purely for the comfort of a child. Although there is a small trade-off in reducing the efficiency of the child’s immune system, a comfortable night’s rest can also go a long way in fighting off a germ.

Lukewarm baths and cool cloths on foreheads can also help to comfort a child, but in general, outside of fever-reducing medications, other interventions do not work well in bringing down the core temperature of the body.

Some parents debate whether to bundle up or strip down a feverish child. It is probably best to do whatever feels most comfortable for the child at that particular time. In the course of a single illness, there may be moments when an extra blanket feels more comfortable, and times when prancing around in one’s underwear feels the best.

FEVER IS A CONTROLLED BURN

One of the reasons that parents are fearful of fever is because they fail to realize that a fever is a controlled burn. The body has a feedback loop with the brain to ensure that the fever does not become “too hot.” Parents sometimes become overly vigilant about bringing a fever down and, as a result, do more harm than good by overusing fever-reducers (and incurring possible side effects).

Even without any intervention (including fever-reducing medications), fevers will stay in a specific range and will not spiral out of control. The fever will eventually break as the infection is defeated, and the body temperature will return to normal.

But, as we have discussed, because fever can make a child uncomfortable, it is perfectly reasonable to make use of fever-reducing medications and other techniques (such as baths) to help make a child feel better. However, intervention is not necessary to control the fever; the body will do that on its own.

A good motto for using fever-reducing medications is, “Treat the child, not the fever.” In other words, a child who is playful but has a 103°F fever does not necessarily need any medication. Conversely, a child who is uncomfortable, but who only has a 101°F fever would benefit from medication (for comfort purposes).

CONTROLLING THE FEVER WILL NOT REDUCE THE LIKELIHOOD OF A FEBRILE SEIZURE

One of the reasons many parents are afraid of fevers is because they have all heard of a child who has experienced a febrile seizure. A child experiencing a febrile seizure will be unconscious and appear to have their eyes rolling backward. Initially, their entire body will be stiff, but eventually this will progress to twitching and shaking. While a febrile seizure appears dangerous, simple febrile seizures are benign, and leave no long-term damage. They are also quite common; nearly 5 percent of children will have a febrile seizure at least once in their lifetime, and many will have more than one.

Once their child has had a febrile seizure, parents will aggressively attempt to control all future fevers. However, it is likely that febrile seizures are not actually triggered by the fevers themselves, but are rather triggered by the same chemical signal pathway that led to the fever; thus, even if you control the fever, the chemical signals can still trigger the seizure. Studies have shown that aggressive management of fever will not prevent a febrile seizure.

Febrile seizures should be evaluated by a doctor but often do not require emergency care. When a febrile seizure occurs, place the child on their side and on the ground away from harmful objects. Do not try to place anything in their mouth, as there is no risk of swallowing the tongue. Time the seizure. If it lasts 5 minutes or longer, call 911. Most febrile seizures will last 1–2 minutes—although it will feel much longer! Once the seizure has ended, call a doctor for further instructions.

A visit to the emergency room for a febrile seizure is generally unnecessary, unless other risk factors are present. It is unclear why some children are prone to febrile seizures. The good news is that even for children who are prone to febrile seizures, not every fever will trigger a seizure and most will outgrow them by 5 years of age.

It is important to note that a simple febrile seizure is different from a complex febrile seizure. A complex febrile seizure is defined as multiple febrile seizures in a 24-hour period, or a febrile seizure that lasts longer than 15 minutes. Additionally, a focal febrile seizure is also considered a complex febrile seizure, and is more concerning than a generalized seizure. A focal seizure is when a discrete part of the body is twitching by itself, as opposed to a generalized seizure where the entire body twitches and shakes. All complex febrile seizures should receive immediate medical attention.

FEVER DECISION TREE

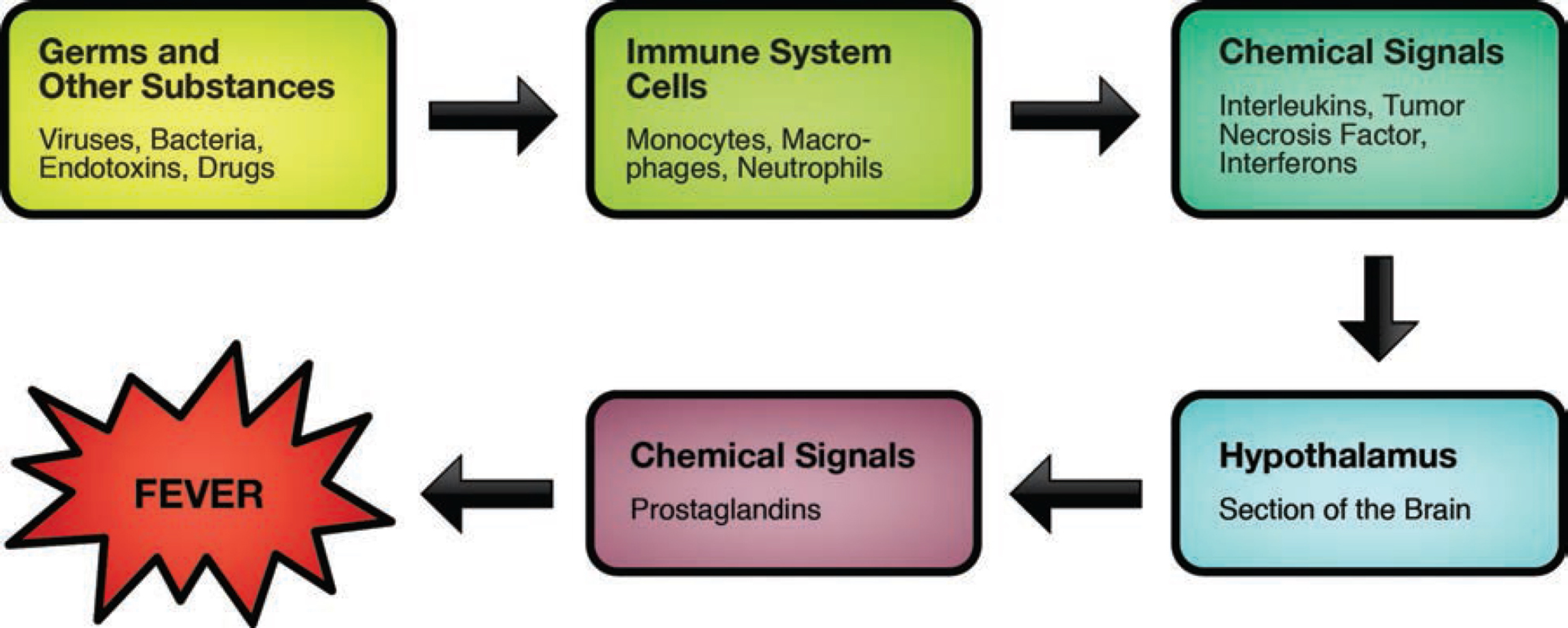

If doctors are not concerned about the fever itself, then what is going through their head when examining a child with a fever? In general, the doctor is trying to figure out what kind of infection is triggering the fever. While the doctor is asking questions and examining a child, they are running through a checklist of possible infections and mentally eliminating those that don’t fit (as shown above).

If the fever is triggered by a common virus, there is unlikely to be any harm from the infection itself, unless a major organ (such as the brain, heart, lungs, or liver) is being attacked. The vast majority of viral infections will resolve on their own without any intervention, meaning there is little to be done.

If the fever is triggered by bacteria, however, there is greater cause for concern. Most bacterial illnesses require antibiotics. If the infection is left untreated, it can oftentimes worsen and lead to harm. Prompt treatment is imperative, especially if bacteria are invading a major organ (such as the brain, heart, lungs, or kidneys).

With common illnesses, distinguishing between a bacterial and viral infection will be easy enough for an experienced parent to discern. However, there will be times that a doctor’s expertise and a physical exam will be needed to help with the determination. Judicious use of tests (such as a strep throat swab or urine/blood tests) may also be helpful; however, an experienced doctor will often not need tests to confirm the diagnosis.

INFANT SICKNESS GAUGE

CHILD SICKNESS GAUGE

GAUGING THE SERIOUSNESS OF AN ILLNESS

So, does every fever need to be seen by the doctor? NO! Most fevers do not need an evaluation by the doctor. As parents become more experienced with their child’s illnesses, they will be able to determine whether a visit to the doctor is necessary, or if monitoring the child at home will suffice.

More important than the actual measurement of the fever is the activity level of the child. Put simply, a child with a serious infection will not play! Rather, a child with a serious infection will get worse from day to day. A child with a serious infection will perk up minimally with a fever-reducer (it may take 30–60 minutes for the medication to kick in).

These charts can help to gauge the activity level of a child. The more active they are, the more they talk, and the more they eat—the less you have to worry. The less active they are, the less they talk, and the less they eat—the more you have to worry.

Again, it is not necessary to treat a fever. However, fever-reducers are helpful in making the child more comfortable and in gauging how sick a child truly is. If a child perks up after taking a fever-reducer, there is little to be worried about. If a child does not perk up after taking a fever-reducer, while it does not necessarily indicate the presence of a serious infection, parents should closely monitor the child and call or visit the doctor to touch base.

Please note that for any infant 3 months of age or younger, any fever of 100.4°F or higher should be reported to the doctor as soon as possible. Young infants give fewer clues that indicate how sick they truly are. Additionally, because they have an immature immune system and have not yet received all their vaccinations, it is imperative to thoroughly assess newborn babies to rule out any serious source of infection. Even in newborns, it is not the height of the fever that is worrisome—it is the possibility that the fever represents a serious infection that most concerns the doctor.

TAKING THE RECTAL TEMPERATURE OF AN INFANT

For babies younger than 3 months of age, the best place to check the temperature is in the rectum (any thermometer designed for taking rectal temperatures is appropriate). For babies older than 3 months, other methods are reasonable. Often, when parents measure the baby’s temperature somewhere other than the rectum, they feel they should add or subtract a degree. When measuring a temperature, it is better not to add or subtract a degree, but to report it as shown by the thermometer.

Noting when the temperature was taken, where the temperature was measured, and when the last time a fever-reducing medication was administered can also be useful information. A simple chart documenting these items can be very helpful.

In children 1 year and older, because activity level is a better gauge for how sick a child truly is, precise temperature measurements are not as important. Any modality of thermometers is reasonable, and vigilant temperature checking is generally not needed.

HOW TO TAKE A RECTAL TEMPERATURE

1. Lubricate the tip of the thermometer with a lubricating jelly.

2. Lay the baby down (facing up) on a firm flat surface, such as a changing table.

3. Grab the baby’s legs securely with one hand.

4. Place the thermometer firmly between the second and third fingers of the free hand.

5. Insert the lubricated thermometer through the anal opening, about ½–1 inch (about 1.25–2.5 centimeters) into the rectum. Stop at less than ½ inch (about 1.25 centimeters) if you feel any resistance.

6. Steady the thermometer between your second and third fingers as you cup your hand against your baby’s bottom. Soothe your baby and speak to them quietly as you hold the thermometer in place.

7. Wait until you hear the appropriate number of beeps or any other signal indicating that the temperature is ready to be read. Read and record the number on the screen, noting the time of day that the reading was taken.

ALTERNATING FEVER MEDICATIONS

As previously mentioned, fever-reducing medication should be used for the purpose of keeping a child comfortable. For children, the two most commonly used fever-reducers are ibuprofen (Motrin and Advil are examples) and acetaminophen (Tylenol). Ibuprofen and acetaminophen work similarly; however, ibuprofen is mainly metabolized by the kidneys, and acetaminophen is metabolized by the liver. Aspirin (which is different from ibuprofen and acetaminophen) should never be given to children except in rare circumstances when instructed by a doctor.

A good approach with fever-reducers is to use only one medication and use it no more than every six hours. If the child appears uncomfortable at the three- to four-hour mark between doses, a second alternative fever-reducer can be used, as needed, to bridge the gap.

For example, a mother could use ibuprofen at 12 pm, 6 pm, 12 am, 6 am and so forth. At 3 pm or 9 pm, if needed, she can use acetaminophen to bridge the gap.

In general, it is best to stick to just one medication. Alternating medications frequently can lead to confusion: There may be miscommunication between parents or forgetfulness, which can result in giving the same medication every three hours instead of every six, leading to accidental overdosing. Overuse of acetaminophen can lead to liver damage, and overuse of ibuprofen can lead to kidney (and in rare cases, liver) damage. A written record of what medication was given at what time can help prevent errors.

Studies show that using one medication works just as well as two in terms of keeping a child comfortable—so err on the side of using just one! Anecdotally, ibuprofen seems to work better than acetaminophen.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

![]() Fevers under 107.6°F are not dangerous; in fact, fever is actually beneficial.

Fevers under 107.6°F are not dangerous; in fact, fever is actually beneficial.

![]() Fever is a controlled burn.

Fever is a controlled burn.

![]() Treat the child for comfort, not for the fever.

Treat the child for comfort, not for the fever.

![]() Simple febrile seizures are not dangerous.

Simple febrile seizures are not dangerous.

![]() The source of the fever is more important than the fever itself.

The source of the fever is more important than the fever itself.

![]() Activity is a better gauge of sickness than the actual number of the fever.

Activity is a better gauge of sickness than the actual number of the fever.

![]() Alternating different fever-reducers is acceptable, but using a single medicine is preferable.

Alternating different fever-reducers is acceptable, but using a single medicine is preferable.

Fever is a controlled burn that the body will regulate; however, fever-reducers can be used to keep a child comfortable until the germ is defeated. Any child who appears to be getting worse over time should be evaluated by a doctor.

Understanding the role of fever in the body can help reduce parental anxiety and prevent the possible side effects from overuse of fever-reducing medications.

Most children will experience fevers throughout the course of their childhood. In and of itself, fever is not dangerous. The most important part of evaluating a fever is to identify the source of the fever. Gauging a child’s energy, interactions, and appetite can help determine the seriousness of the illness.