1

MEDIATOR OF FASCISM: SHIMOI HARUKICHI, 1915–1928

Fascism has only three principles: the ancestral land, duty, and discipline.

—Shimoi Harukichi, 1925

In 1924, Shimoi Harukichi returned to Japan after a decade’s long stay in Naples and Rome. Having witnessed the destruction wrought by World War I, he announced that under Benito Mussolini’s Fascist government Italy was experiencing an unprecedented resurgence. The fourteenth-century Renaissance, he proclaimed, had been “a revival of the arts, but the renaissance that happened during the war was the great renaissance of all the nation.” The result, he argued, was Fascism, a movement that “opened the people’s eyes, unifying them and making them one with the state.” In other words, Fascism was an Italian “spiritual movement.”1 Yet, Shimoi continued, the Fascist aesthetics of heroism, sacrifice, and war mirrored the essential traits of what he understood to be Japan’s cultural essence. “Japan’s way of the warrior [bushido], that ancient morality and spirit, is completely identical. I believe the Blackshirts and their truncheon are manifest in Japan’s loyalty to the emperor and patriotism [chūkun aikokushugi].”2 To Shimoi’s mind, then, a timeless spirit of patriotism was characteristic of both Japanese and Italian history and bonded the two countries. Fascism was a manifestation of this spirit, and he made it his life’s endeavor to convey this conviction to a Japanese audience.

In the 1920s Shimoi became known as the most indefatigable propagandist of Italian Fascism in Japan. However, this characterization is only partly correct.3 Paradoxically, despite his efforts to herald the achievements of Fascist Italy, Shimoi advocated that fascist change in Japan take a different route. He admired Fascism and its Duce but did not aim to replicate a seizure of power or a leader such as Mussolini; rather, he sought to mediate the story of Italian Fascism to an audience of young Japanese in order to stir them into seeking a patriotic politics of their own. As he would proclaim in later years, “Fascism is a typically Italian phenomenon: it would be a mistake if [it] were to try to cross borders and upset the systems of other states. The life of Fascism depends on fascism itself, that is, on its own men.”4 To Shimoi’s mind, the Japanese already possessed the patriotic spirit that Italians were displaying in their Fascist resurgence; they just failed to realize it. Telling the story of Italian Fascism as a narrative of ordinary heroism, patriotic sacrifice, and social order would act as a catalyst in Japan, making Japanese conscious of the values surrounding the nation and disciplining them into becoming obedient citizens.

The premise that fascist change depended on the Japanese recognizing the spiritual commonality between Japan and Italy was what distinguished Shimoi from his contemporaries. From the 1920s, Fascism did indeed attract the attention of many observers in Japan, as elsewhere in the world, but no one found in Fascism the deep links that Shimoi had detected.5 Rather, the early Japanese debates on Fascism intersected with a discourse on political and cultural reform that swept across the ideological landscape of this period.6 Liberal observers commented on the violence that characterized the Blackshirts. Fascist “private groups, whose actions are beyond the law,” wrote the journalist Maida Minoru, threatened not only freedom of expression but, effectively representing the establishment of “dual political organs,” imperiled the state of law itself.7 Marxists, who called for social revolution, saw in Fascism a sign of bourgeois reaction. In the eyes of the communist leader Katayama Sen, then stationed in Moscow as a Comintern officer, Fascism bolstered bourgeois rule “as a reactionary force and as a powerful representative of the capitalist class [that] is hardening the ground for the capitalists in view of a renewed conflict.”8 On the other side of the spectrum, right-wingers welcomed the Fascists as a force against communism. Ninagawa Arata, an adviser to the Japanese Red Cross in Geneva and a member of the Japanese mission to the Washington Conference (1921–1922), praised the “extirpation” of Marxism at the hands of the Fascists, even arguing that they had enacted “true democracy…unlike Lenin, they are not despotic, nor destructive, for in reality they are constructive, democratic [minshuteki].”9

As these appraisals show, Fascism was a subject of public debate from early on. Yet in the eyes of many ideologues Fascism’s practical and theoretical applicability to Japan was problematic. Fascism did not carry the clout of liberalism and socialism: in the 1920s few even considered it a fully fledged ideology with a coherent doctrine encompassing politics, economics, and culture. Indeed, initially Japanese focused their debates on the Fascists—that is, the actions of individuals, the Fascist Party, or its leader, Benito Mussolini—more than on discussing fascism as an ideology. That fascism was a term in flux is also evident from its Japanese spelling: the transliteration of the word “fascism” as fashizumu became standard only in the early 1930s.10 The association of Fascism with Italy also contributed to its limits. In the Japanese cosmology of the “West,” Italy did not occupy a privileged position: since Japan’s first contacts with Europe, Italy remained a destination for artists, adventurers, and the handful of scholars who, by means of English literature, had developed an interest in the exotic peninsular home to Ancient Rome; Japanese politicians, economists, and intellectuals took inspiration from their German, British, and French counterparts.11 How could Italy suddenly generate an ideology capable of competing with the intellectual traditions of its neighbors?

Shimoi made a virtue of Japan’s relative lack of interest in Italy, promoting the notion that Fascism was a patriotic movement, led by robust young leaders such as Mussolini, to rescue a nation that had been betrayed by socialist revolutionaries and an ossified, liberal ruling class. This interpretation mirrored the official Fascist discourse, but at the same time it was closely connected to Shimoi’s thought as it developed in the late Meiji period (1890–1911). This link is particularly evident in the theme of youth. In Shimoi’s narrative of Fascism, youth is presented in the highly aestheticized terms characteristic of late nineteenth-century romanticism as the social group that, through its virility and poetic sensibility, is capable of effectuating a broader national awakening. Youth also reflected Shimoi’s conviction as a conservative educator that training young people with national morals was the basis for social order. Cultural romanticism and social conservatism merged in his understanding of World War I, which he experienced in Italy. For him, the war had enabled youth to express their vitality, but in a controlled, socially safe manner: by dedicating their energy to the nation. Regarding Fascism as a continuation of the mobilization of youth during wartime, he came to understand this ideology as a kind of updated nationalism for the age of the masses.12

The significance of Shimoi for the history of fascism in Japan, therefore, lies not so much in his peculiarity or his many, often bizarre, enterprises to bring Japan and Italy together. Rather, by considering his role as a mediator it will become clear that his understanding of Fascism was produced between Japan and Italy through a process that reveals the marks of a right-wing activist who merged the romantic sensibility of a late nineteenth-century romantic with the anxieties of a conservative educator—all expressed in the language of Italian Fascism. In this sense, Shimoi was less idiosyncratic than he liked to style himself. Indeed, his ideas were often banal, crude refashionings of the mainstream views he encountered during his life, both in Japan and Italy. And yet the popularity of Italian Fascism that he contributed so much to generating in the 1920s is evidence that, like him, many Japanese recognized Fascism as an Italian story with wider, transnational, meanings.

A Late Meiji Educator

Shimoi may have stood out for his stance on Fascism, but before he left for Naples in 1915, he was an archetypal middle-class youth of the late Meiji period (1890s–1911). The generation of ideologues, writers, educators, and politicians who came of age in this period held a view of the world that was colored by a deep ambivalence toward modern mass society. They no longer enjoyed the degree of social mobility, of “rising in the world” (risshin shusse), that was open to the schooled generation that had preceded them. In response, this “anguished youth” (hanmon seinen), as they were sometimes called, denounced the culture of materialism associated with business.13 They lamented the lack of a raison d’être in modern civilization, delighting instead in a romanticism drawn both from contemporary Japanese literature of the likes of Yosano Akiko, Kitamura Tōkoku, and Shimazaki Tōson, as well as from the neo-romantic German works of Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, and Robert Musil. Spurred by the wave of nationalism after Japan’s victory over Russia (1905), they turned away from socialist critiques of society, forming instead a discourse on social redress based on civil morality and loyalty to the state and emperor.14

From an early age, Shimoi demonstrated an eagerness to rise in society, as is evident from his move from Asagura-chō, a village in rural Fukuoka prefecture on the southern island of Kyūshū, to Tokyo. Born in 1883 as Inoue Harukichi, Shimoi was the son of an impoverished former samurai whom the agricultural crisis of the 1890s had forced to seek employment in the coal mines near his hometown. It has been speculated that, through his father’s connections, Shimoi became familiar with right-wing organizations such as the ones headed by Tōyama Mitsuru, many of which originated around Fukuoka.15 Although in later years Shimoi would indeed be close to Tōyama, in his younger years his primary concerns were with gaining an education. Shimoi’s father, Kikuzō, was able to provide Harukichi with a privileged education. He attended both compulsory primary school and the optional middle school, from which he graduated in 1902. By all accounts Harukichi was a bright student and, following a practice common for the times, Shimoi Kasuke, a wealthy trader in timber from Tokyo, adopted him and arranged for him to marry his daughter Fūji in 1907. It is unclear why Kasuke, despite having a son of his own, Eiichi (who, influenced by Harukichi, would become an Italian literary scholar), intended to make Harukichi his successor. In any case, it was an unfortunate decision. Although Harukichi strove to make it to the capital, he had no intention of becoming a businessman.

In fact, Shimoi disdained the prospect of pursuing a materialist career. Two reasons account for this attitude, both related to his training at the First Normal School in Tokyo, which he entered in 1907. As Donald Roden has shown, two very different streams of thought coexisted at this institution. There was the conservative side. The normal schools had been established in the 1880s by the architect of the Meiji education system, Mori Arinori, as stepping-stones to the Imperial universities and as the training ground for teachers and bureaucrats who were to educate and administer future generations of Japanese in the spirit of Meiji ideology. The instruction in these schools was strict, with an emphasis on inculcating moral values that would create an orderly society and self-abnegating national leaders.16 On the other side, at the normal schools students were also immersed in the romantic culture of late Meiji, exploring their feelings as individuals through literature and literary clubs. Indeed, even before entering these schools, many students were steeped in popular adventure novels that promoted ideals of heroism, courage, and chivalry.17 This romanticism antagonized the perceived material civilization of the West—and its Japanese supporters—turning instead to a valorization of the timeless qualities of the Japanese nation. In this environment Shimoi reworked the relationship between the conservative “morality of doing” and the voluntaristic individualism that derived from romanticism, conferring on the educator the role of remaking national subjects through the mobilization of the spirit of Japan.18

The occasion for putting these assumptions into practice came with the Ōtsuka kōwakai, a movement Shimoi founded at the Tokyo Normal School to further the publication and dissemination of children’s stories. The publication of children’s stories had undergone a rapid expansion in late Meiji, when efforts were made to modernize them. The resulting genre incorporated the kind of nationalism that emerged as a result of Japan’s ascendancy in East Asia, but under one key promoter, Iwaya Sazanami (1870–1933), it also revamped traditional folktales, merging them with contemporary themes of military valor, individual heroism, and devotion to country and emperor. Amid the sense of social crisis of the early 1910s, folktales expressed an ideal of community in which individuals lived in harmony with each other and the nation.19 For this reason Shimoi’s group saw the genre as a way to reeducate Japan’s youth in civil morality.

With this goal in mind, Shimoi wrote what would become his first, and very successful, publication, Ohanashi no shikata (How to Make Tales), a manual on how to tell moralistic stories based on folktales. Revamping the production of folktales, then, was not Shimoi’s only goal in Ohanashi no shikata. Perhaps more crucial to its author was the task of educating educators. “Oral folktales [tsūzoku dōwa] are one great form of education. Yes, an education. But even though they are about education, educators are surprisingly indifferent to them. I want them to become passionate.”20 Hence oratorical methods of delivery were the focus of the book. In other words, modernizing folktales for the age of the masses meant stressing how something was narrated, not what was narrated. The pitch of one’s voice, the choice of words, expression, the use of gestures, and the structure of the tale—these were all points that Shimoi elaborated in order to provide educators with the means to capture the attention of Japan’s youth. Rhetoric (yūben) was an important part of Meiji educational culture and was taught in classes and clubs as a means to create independent and elite political subjects. Shimoi wanted to reform this project. In his view and that of other ideologues of late Meiji, in the age of mass society it could no longer be assumed that the individual would identify with the nation; indeed, left in the hands of individuals, rhetoric could prove to be a threat to the nation. So, in order to revitalize the connection between the individual and the nation, Shimoi believed that rhetoric should reside in the hands of the teacher, a figure that stood safely halfway between civil society and the state. “I pray that through this new field in education—folktales rhetoric [tsūzoku kōwa]—educators will take the opportunity and press on to become a vanguard [kyūsenpō].”21

As it turned out, Shimoi relinquished his goal to be at the forefront of Japan’s educational innovation, preferring instead an appointment as a lecturer in Japanese at the prestigious Royal Oriental Institute in Naples, where he moved in 1915. Personal advancement abroad trumped concerns over Japan’s social morality. In later years he would claim that it was his love for Dante, whom he had discovered as a student, that led him to Italian shores. More likely, however, the romantic, decadent, and antique image of Italy, as portrayed in the English and German literature that Shimoi had read at the normal school, had aroused his curiosity. A determination to rise in society, romanticism, and a sense of adventure convinced him that his own interests were just as important as those of Japan.

Poetics: Naples, World War I, and Gabriele D’Annunzio

“It is much easier here than in Japan to achieve success as a literary person [bungakusha],” Shimoi wrote to his younger brother Eiichi in 1920.22 He could say this with some confidence, as in the half-decade he spent in Naples Shimoi had risen from an obscure Japanese educator to a “poet” whose reputation extended from Italy to his country of origin. During this time, he demonstrated a remarkable capacity to connect to Italian, and especially Neapolitan, elites. Though he came to the attention of such prominent individuals as Prime Minister Antonio Salandra and the chief of general staff, General Armando Diaz, it is clear that Shimoi even more ardently cherished the hope of entering into the local intelligentsia, particularly literary and artistic circles. Within these, it was poets whom he befriended with greatest dedication. His background as a “literary youth” only partly accounts for this inclination. More critical to his acceptance was the unexpected and keen interest in Japanese poetry on the part of local poets. Whether of the modernist kind, such as the Neapolitan group that formed around the journal La Diana, or the romantic bent, such as Gabriele D’Annunzio, Italian poets wanted to know more about Japan and pursued Shimoi as a source of knowledge about the country. Although he was neither a scholar nor a poet, Shimoi was only too happy to receive such epithets, convinced that Italians had recognized his intellectual talent.

Sidelining his background as an educator for a career as an amateur poet and literato had a profound effect on Shimoi’s perception of the present. As emerges from his publications, he developed a highly aestheticized appreciation of the changes brought to Italian culture and society during this period. He came to this understanding, first of all, through his experience of World War I. Poets, it appeared to him, had played a crucial role in producing the patriotic sentiment that united Italians to fight for their country. At his arrival in 1915, Italy was on the brink of entering the conflict, and several literati, most famously the futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the Florentine modernists Giovanni Papini and Giuseppe Prezzolini, as well as the romantic Gabriele D’Annunzio, were extolling the virtue of the war as a way to rejuvenate Italians and Italian culture.23 But Shimoi also believed that he had contributed personally to the surge of national sentiment through his collaboration with La Diana; by introducing the journal to Japanese poetry and culture, he claimed a place in the revitalization of Italian poetry and patriotism. This mediation led him to the conclusion that Italians and Japanese shared an inborn patriotic spirit that emerged from the compatibility of their literary traditions. In short, he claimed to have uncovered a privileged aesthetic and spiritual link between Japan and Italy.

La Diana was a prime example of the vibrant avant-garde movements of early twentieth-century Naples. In the late nineteenth century Naples had undergone a decline in comparison to the rapidly industrializing Milan, bureaucratizing Rome, and tourist-trapping Florence and Venice.24 Yet it remained a large city with a proud history of grandeur. La Diana was founded in 1915 by the Buenos Aires–born Gherardo Marone (1891–1962), a young law school graduate who had turned to letters. In line with other, more established, contemporary modernist journals such as La Voce, Marone’s publication addressed the burning question of the day: how to reinvigorate Italian culture, and Italians along with it. The name of the journal, which translates as “reveille,” was probably chosen with that idea in mind, and, for Marone, the war signaled that wake-up call. Championing the “moral value of every great war,” he argued that such a conflict “no longer generates class conflict…but a superb idea which, purifying and sublating the spirit, reaches the ideal of pacification.”25 La Diana was a loose group that included a mixed crowd of poets, artists, and literati, who broadly subscribed to this ideal. Among the contributors were high-profile national intellectuals such as the philosopher Benedetto Croce and the poets Umberto Saba, Giuseppe Ungaretti, and Corrado Govoni, as well as little-known figures such as Lionello Fiumi—and the thirty-two-year-old Japanese Shimoi Harukichi.

Shimoi, who had never written poetry before, managed to command the attention, even the admiration, of these poets because he arrived in Naples at a time of transition in the Western discourse on Japan. Fin de siècle Europe had exoticized Japan in the cultural wave known as Japonisme. The late nineteenth-century impressionist painter Van Gogh, for example, drew inspiration from Edo period (1600–1868) Japanese arts and woodblock prints. In Italy, the composer Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly also reveals interest in traditional Japanese culture, just like the early aesthetic sensibilities of D’Annunzio.26 Japan’s military victory over Russia in 1905, however, prompted some European intellectuals to enquire about the country’s modern literature. To most Italians, of course, contemporary Japanese works remained out of reach for lack of translations; only a handful had traveled to the country. In this context Marone saw in Shimoi a direct point of access to Japanese culture unmediated by Paris or London, the two cities from which Japonisme had spread across Europe. Shimoi was quick to understand Marone’s overtures and without much ado climbed into this new intellectual niche.

What excited the Neapolitans was the haiku, a seventeen-syllable poem. The haiku spoke to La Diana’s attempt to carve out a middle ground in Italian modernism because it balanced conciseness with emotion, exemplifying a free verse that did not capitulate to what many considered futurism’s soullessness.27 Shimoi, together with Marone, set out to translate the work of a number of contemporary modernist poets, focusing on Yosano Akiko and Yosano Tekkan’s Myōjō, the journal of the New Poet Society (Shinshisha), published in Tokyo between 1900 and 1908. Translations of the two Yosanos and other Japanese authors appeared regularly in La Diana after 1916. The initial reception was positive and prompted Marone and Shimoi to publish a separate collection, Japanese Poems (Poesie giapponesi), in March 1917. The booklet caused a small sensation, both within the circles of La Diana and in the broader literary field. Giuseppe Ungaretti, soon to become one of Italy’s most distinguished, and nationalist, twentieth-century poets, was sent a copy of the publication while he was in the trenches. He wrote to Marone thanking him for the volume. “Now I shall enjoy them; and with you accede to the world of enchantments.”28 The poems were reviewed in a dozen newspapers in Italy, and Giovanni Papini appraised the poems in the prestigious Parisian symbolist journal, Mercure de France.29 The literary critic Goffredo Bellonci had misgivings about the poems, claiming that the poets translated by Shimoi and Marone did not actually exist and were, in fact, written by Marone himself. It was necessary to call in the Japanese embassy to vouch for the existence of these Japanese poets.30

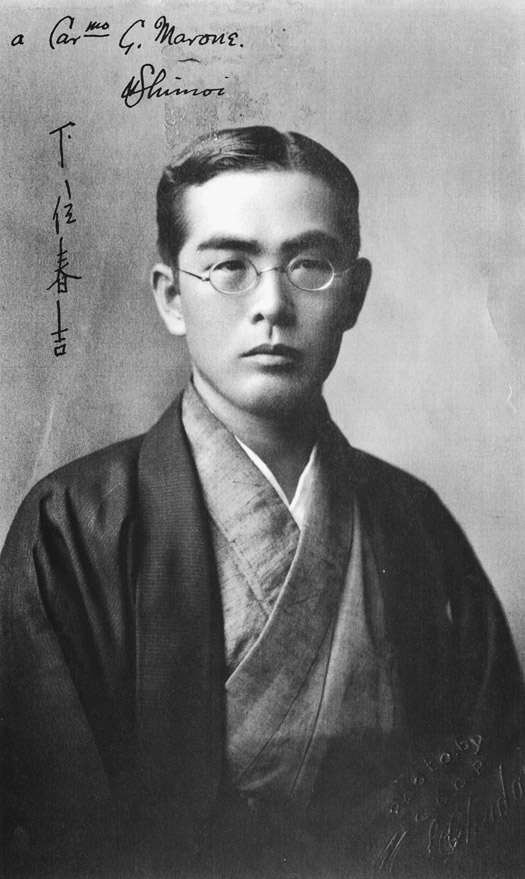

Shimoi Harukichi, Naples, ca. 1916.

(From Gaetano Macchiaroli, ed., Gherardo Marone [Naples: La Città Nuova, 1996].)

La Diana stirred Shimoi’s belief that Italy and Japan stood jointly at a turning point in their modern histories. It seemed to him that La Diana and Myōjō headed an altogether parallel project to revitalize national culture through aesthetic forms capable of safeguarding the old in the new. Myōjō, they argued, exemplified the desire to overcome past literary forms. Just as Myōjō had devised new forms for the age-old tanka, so La Diana sought to revive older Italian styles without compromising Italy’s national essence, as stated by Shimoi and Marone in their introduction to Japanese Poems: “A sudden revolutionary movement in the fields of art, which began in the first few years of the twentieth century, created in Japan a new poetic era, the contemporary and most interesting one…which stands up to the most dignified European avant-gardist movement.”31 Ungaretti confirmed this sentiment in a letter to Marone.

My dear Gherardo, for a century, in the series of schools that have been succeeding each other in our Western countries, poetry has been renovating itself, refreshing itself, purifying itself in contact with all kinds of poetry; I do not know the Japanese who have preceded yours, and I do not know what and how much we owe to them; but it seems to me that you wanted to prove that a Westerner of a certain refinement could, nowadays, doubtlessly write like Yosano Akiko and vice versa.32

As far as Shimoi was concerned, his two years of collaboration with the Neapolitan modernists had been a success. He had achieved a social status he could not have dreamed of in Japan. Moreover, to his mind, he had played a central role in shaping the poetics of La Diana and, in turn, in revitalizing Italy’s national culture. In so doing he also came to see himself as the pivot in an as yet fledgling spiritual connection between Japan and Italy. Yet when the war caused La Diana to cease publication in 1917 Shimoi did not despair. Naples felt far from the trenches where, it seemed to him, Italians were fighting for their country’s survival. The front in Italy’s northeast appeared more exciting than the salons of Naples. Why else did Italian poets from D’Annunzio to Marinetti and Ungaretti flock to the front line? The contained, introspective lyricism of La Diana could not express Shimoi’s war fever.

La Diana had confirmed for Shimoi that poets played a key role in the rejuvenation of the national spirit, but it had not convinced him, as an educator, that they could also transform ordinary Italians. It was the experiencing of war, Shimoi felt, that spread the patriotic fervor proclaimed by these poets among the wider population. In late 1918 he toured the Italian front. It seemed to him that patriotism emerged spontaneously in the everyday lives of soldiers and civilians alike. For this reason World War I became central to Shimoi’s thought, leading him to praise war for the aesthetics of camaraderie, sacrifice, and death that it generated among soldiers.33

Shimoi expressed these feelings in The Italian War (La guerra italiana, 1919), his memoir of the front. It was, in many ways, an unremarkable publication. It replicated the tropes of the nationalist literature that glorified masculine courage, camaraderie, and devotion to one’s people, articulated perhaps most crudely in Ernst Jünger’s accounts, which appeared throughout Europe in the years after the conflict.34 Yet, despite its banalities, it reveals how the war marked a period of shifting alliances for Shimoi.

The Italian War suggests the desire, and the confidence, on the part of Shimoi to distance himself from his Neapolitan milieu. In the book he sought to garner a readership that was both national and not strictly intellectual. For this reason he sprinkled the book with his correspondence with the highest political and journalistic personalities, whose letters of reference he needed in order to visit the Italian front (he did not actually fight, despite being sometimes anxious to give this impression). Francesco Saverio Nitti, the finance minister, stated that Shimoi was a “distinguished Japanese writer and sincere friend of Italy.” The minister therefore asked Giovanni Visconti Venosta, the secretary of the head of the joint chiefs of staff, to “introduce [Shimoi] to General Diaz and to find a way to have him visit our front with due care.” Guelfo Civinini, a nationalist journalist of some repute who wrote for the conservative Milanese daily Corriere della Sera, introduced Shimoi to the Supreme Command’s Section for Photography and Cinematography.35

The Italian War was a work of transition also in Shimoi’s poetic taste. While bearing the hallmark of romantic lyricism, it also displays elements of futurist origin. Shimoi effusively wrote about his perception that order, self-sacrifice, and camaraderie helped soldiers to set aside regional identities and class conflict and embrace each other as Italians. In writing the book, he claimed that he was offering the “simple but sincere words of affection and admiration of a Japanese” to those “old fathers who offered their sons in the name of the sacred fatherland [patria]…to the simple soldiers [who] after the sorrowful life of four years in the trenches…return now to their ploughs and hammers, content and happy.”36 In the war, he argued, Italians found the nation in their everyday lives. He praised the bravery in ordinary people, “those many heroes, young and old, [who] every day are actors in moving scenes without being remembered by anybody.”37 A scene of an old man, women, and children sitting near their dilapidated house around a makeshift hearth expressed Shimoi’s ideal of nationalism: “Love of the hearth is the sacred origin of love of the fatherland.”38

But now futurism slipped into his writing, revealing how Shimoi found in war not only an occasion to contemplate people’s patriotism but also an exciting transformative experience. As if to vindicate Marinetti’s boast that war was the world’s only hygiene, Shimoi found the war “majestic”: “The word ‘war’ conjures up an idea of agitation, confusion, disorder, disquiet…but here dominates a perfect calm. You won’t find the disorder that there is in Rome or Naples. What an ideal order! Discipline is being maintained; the streets are all clean; women, boys, old men all work in silence and full of faith. What a beautiful scene!”39

Shimoi also evoked that other object of futurist fetish, the automobile. For him speed denoted modern efficiency while encouraging the transformation of everyday customs. When “flying in a car,” he remarked, a military salute was more practical than greeting by taking off one’s hat.40 Nor was futurist masculinity absent from his sentiments. Crossing a river he observed, “what a masculine excitement [eccitazione maschia]! Traversing a stream flowing at two-and-a-half meters per second, in an iron boat, under tremendous enemy fire!”41

The most significant turning point in The Italian War was Shimoi’s relationship—personal, poetic, but also fictitious—with Gabriele D’Annunzio. Shimoi found him irresistible, a poet who wedded romanticism to an uncompromising and eroticized nationalism while also being a man of action. A high-profile figure in national politics, D’Annunzio volunteered to fight in the war at age fifty-five, flying bombing raids on enemy cities. To Shimoi, he represented a warrior-poet engaged with the real problems of the nation. Shimoi’s infatuation grew deeper after the two actually met, though in unclear circumstances, on the front. In a letter with which Shimoi prefaced The Italian War, D’Annunzio wrote in his usual effusive tone: “We spoke of Italy, the painful one, we spoke of our sacrifice, our blood, of the desperate days and our undefeated hope. Do you remember? I suddenly saw two vivid teardrops flowing from your stranger’s eyes. And then I recognized you as a brother; and my heart opened.”42

It remains unclear how sincere D’Annunzio declarations were. Shimoi, however, was determined to exploit the poet’s overtures in an effort to reconceive his life after World War I. First, he followed D’Annunzio in the expedition to Fiume. The case of this city, claimed by both Italy and the newly formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia, became a cause célèbre for Italian nationalists. To them, Fiume exemplified all that was wrong in postwar politics. They argued that the government had failed to gain adequate territorial compensation for Italy’s war effort and the over six hundred thousand Italians who had died in the conflict. The acquisition of Austrian-held Trentino, Trieste, and Istria was not enough, leading D’Annunzio to announce that Italy’s was a “mutilated victory.” He was irate over what he saw as the government’s lack of determination to resolve the contention over Fiume in Italy’s favor. In September 1919 he took matters into his own hands and invaded the city with his army of war veterans, the legionari, declaring it an independent Italian state under his command. Only in December 1920, after a bombardment by the Italian navy, did he surrender the city.

For Shimoi, the Fiume episode signaled that an age had arrived in which artists, and especially poets, spearheaded moral reform by forging national unity through performing exemplary acts of patriotism. D’Annunzio’s leadership left a profound mark on him. Contemporaries and historians alike have commented on the innovative style pioneered by D’Annunzio during the yearlong occupation. He crafted a militaristic-authoritarian rule and combined it with a symbolic apparatus that included the Roman salute, dramatic speeches delivered from his balcony, and a cult of his persona. Shimoi, like many veterans who participated in the occupation or observed it closely, as Mussolini did, was deeply impressed. Disregarding the legionari’s debauchery—they violated such taboos as sexual freedom, homosexuality, drug use, and nudism—in later years Shimoi emphasized the heroic narrative of Fiume, claiming a part in it.43

There was another, more material side to Shimoi’s experience at Fiume. He realized that his presence in the city was opening the door to fame for him in his home country. Japanese newspapers reported on the independent republic formed by the boisterous Italian poet, commenting in great detail on the presence of a Japanese there and his seemingly crucial role. Japanese literary circles had been familiar with D’Annunzio since the early nineteenth century. His novel Triumph of Death (1894) was translated into Japanese by the critic Ikuta Chōkō in 1913 and met with great acclaim. Now, too, his image as a daring aviator and showman prevailed among a broader and more popular audience.44 Shimoi, drawn into the international dimension of D’Annunzio’s invasion, instinctively understood the potential of this association and exaggerated his position as his close collaborator, capturing the attention of the Japanese readership.

Shimoi’s second aim was therefore to popularize D’Annunzio—and by implication himself—in Japan. To do so, he attempted to convince D’Annunzio to fly from Italy to Tokyo. It was not an entirely absurd idea. He could count on D’Annunzio’s interest in Japan and his inclination for daring flights (in the war, he had flown over Vienna, dropping propaganda leaflets). Authorities in both countries supported the idea. The Italian government, to whom D’Annunzio was an embarrassment and a nuisance, reasoned that its interests would be served if the poet left the country and tried to facilitate the flight.45 Even the journalist and leader of the nascent Fascist movement, Benito Mussolini, enquired about the possibility of obtaining a seat on a plane.46 Japanese authorities also responded to the idea with enthusiasm. The military, in particular, were eager to study the advanced Italian airplane technology. On September 12, 1919, the cabinet secretary allocated the generous sum of 77,600 yen for receiving the poet and for the logistics associated with the event.47 The army minister, Tanaka Giichi, expressed his support, stating that the Italians could use Japanese military facilities in Korea and on the main islands and that the army would provide refueling and technical support.48 In addition, the minister believed that, thanks to D’Annunzio’s proven credentials as a man “of patriotic thought,” the event would not only “improve relations between the two countries” but would also be “important for the awakening of the Japanese people.”49

D’Annunzio himself, however, was only half-committed. While appearing genuinely interested in the enterprise, he subordinated the flight to his political plans in Italy. On three occasions between late 1918 and early 1920 he and Shimoi discussed the possibility of his flying to Tokyo, but each time he called off his participation. In March 1919 he wrote to Shimoi expressing his excitement about the idea of flying to Tokyo on his “stork of fire” but turning down Shimoi’s “magnificent invitation” due to the death of a copilot.50 A second plan was in preparation but was set aside when, in September 1919, D’Annunzio led his legionari into Fiume. He finally called off the idea in January 1920. “I had hoped to see the peach blossoms in bloom in the land of Tokyo, and to be able to compose verse in competition with one of your delicate poets in an idleness which would have been sweet after such a long, iron discipline.” Finding more pressing business in Fiume, however, he urged Shimoi to “carry to your brothers in the country of the rising sun Fiume’s salute and Fiume’s violets which, today, are the most fragrant in the world.”51 Three days later, perhaps as a consolation, D’Annunzio hosted a dinner in honor of “the guest from the Orient.” Flattering Shimoi, he praised how “in his little chest he had a big Italian heart, and today, under the star of Fiume, a most fiery Fiume heart.” He took the occasion to express his admiration for Japan’s “rebirth”: “What historical fact is comparable in its greatness to the Asiatic resurrection, to the sudden rejuvenation which is renovating sacred Asia, that region of broad and sublime unity?”52

Thanks to the official and public excitement over the possible flight to Tokyo, Shimoi achieved the status of a minor celebrity in Japan.53 The Japanese press followed the event closely. Maruyama Tsurukichi, secretary in the Government-General of Korea and “friend” of Shimoi, explained that Shimoi was a worthy graduate of the Normal School, a “writer” (sakka) and “Dante scholar,” who had received an award from the Italian consulate in Tokyo to teach at the Oriental Institute in Naples, where he had exerted himself to introduce Japanese culture.54 Articles also reported on Shimoi’s activities during World War I and at Fiume, where he and the “great poet” D’Annunzio became “like brothers.”55 Curious journalists interviewed Fuji, the wife of “the poet of Naples,” as well as his son Fujio and daughter Fujiko, both too young to remember their long-departed father, enquiring about Shimoi and their feelings about the seemingly imminent reunion.56 Photographs of Shimoi appeared for the first time in Japanese media. Fond of posing in kimono for an Italian audience, Shimoi found his Fiume uniform more suitable for his compatriots.57

One Japanese whose passions were stirred by news of the flight was the romantic poet Doi (Tsuchii) Bansui. In the January 1920 edition of the magazine Chūō kōron he published a long poem (chōshi) entitled “On the flying horse” (Tenba no michi ni) dedicated to Italy and the Italian poet. Doi, in Shimoi’s view “a brother of D’Annunzio in opulence of style, taste for exuberance, and the hallucinating airiness of his constructions, launched his words of fire for the Italian poet.”58

Neither weapons nor treaties,

—shadowy methods of tricksters

will merge the remote continents;

only the hand of poetry.

And it shall be you, king of the eternal spaces,

Poetry of Italy incarnate,

To preach in the skies

To the most distant peoples, life.59

Statements such as Doi’s prompted Shimoi to change his outlook on Italy, Japan, and his own position between the two. He had arrived in Naples as a middling educator with the intention to further his career abroad. That he left his family behind in Japan was no doubt because he did not foresee remaining in Italy for long. But the collaboration with La Diana, the experience of war, and his relationship with D’Annunzio had a profound effect on him. It seemed to him that Italy had become a land of opportunity, with high-profile politicians writing on his behalf. Perhaps more significant was his conviction that Italy and Japan shared a poetic sensitivity, as he had witnessed during his work with Marone, and as the lyricism of the likes of D’Annunzio and Doi confirmed. Shimoi concluded that World War I had effected a world-historical change, wherein poets were thrown back at the vanguard of history by playing a key role in forging national unity, and that he himself had helped to bring this about.

Politics: Rome, Fascism, and Benito Mussolini

So intrigued were Japanese about Shimoi that in May 1921 the daily newspaper Asahi dispatched a journalist from Paris to investigate this much discussed figure at first hand. The correspondent described Shimoi’s cultural ambassadorship as an “epic work,” calling him “Italy’s Lafcadio Hearn,” after the English-American writer who popularized Japan in the West in the early twentieth century. “I have no doubts,” he wrote, “that Shimoi…has a true grasp of Italy’s spirit [seishin] thanks to his Japanese heart [ki].”60 Showered with praise, Shimoi decided to continue his work as mediator after World War I, but changed his target. After a brief attempt to popularize Japanese literature and art in Naples, he stood his campaign on its head and focused instead on introducing Italian culture to Japan. This shift in the direction of his efforts coincided with a move from poetics to politics. To be sure, Shimoi’s aesthetics had always had a political undertone as a conservative social critique. But now politics became a conscious factor in his search for a rationale for an Italo-Japanese spiritual alliance, one that led him toward Benito Mussolini and Fascism.

Shimoi’s wartime experience and postwar soul-searching made him deeply interested in Mussolini’s rapid rise to political prominence. “First-hour” Fascists, as the early activists are known, had been staunch interventionists who believed in the necessity for Italians to fight in World War I and who, in peacetime, continued the struggle against internal enemies, namely socialists, communists, and left-wing trade unions. During the so-called two Red years (1919–1920) Fascist squads, often led by ex-army shock troops (and often with the aid or compliance of the authorities) unleashed brutal campaigns against the political Left, intimidating, torturing, and killing their opponents. Mussolini, himself an ex-soldier and interventionist, succeeded in wielding loose control over the early Fascist movement, transforming it into a political party, the Fascist National Party (PNF) in October 1921. Having gained, by May 1922, a membership of over three hundred thousand, Mussolini now had a base that enabled him to compete in national politics. With few serious opponents among his own party and the Liberals or Socialists, he was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III in October 1922 (Fascist propaganda preferred to mark the event through the “March on Rome,” when bands of provincial Fascists moved into the capital). After governing as prime minister until 1924, Mussolini expanded his personal powers, outlawing the opposition and becoming, by 1926, dictator of Italy.61

It took Shimoi some time to adjust to the “new man” in Rome and to set a new agenda for himself. Immediately after the war, he returned to Naples to pursue his work of introducing Japanese culture to Italy. Now, however, he conceived it as a venture in which he was the main protagonist. Supported by his fame and for a while by the Japanese Embassy, he became a regular tour guide for Japanese visitors to Italy, high and low alike. For instance, he accompanied the romantic writer Tokutomi Rōka who, during his journey around the world, visited Naples in July 1919. Tokutomi later related how Shimoi informed him of his and D’Annunzio’s plans to fly to Tokyo and how, startled, he had set to work immediately on a celebratory poem to send to the Italian poet.62 In July 1921, the Japanese Embassy appointed Shimoi a “temporary employee” (rinji shokutaku), probably as translator, during the visit of Crown Prince Higashinomiya, the future Shōwa emperor. The august traveler “praised” the “activities” of his subject, who displayed two large Italian and Japanese flags on boats anchored off the island of Capri where the monarch was to pass as he set sail to leave Naples.63

Also a reflection of Shimoi’s prewar activities was the journal Sakura (Cherry Blossoms), published between June 1920 and March 1921. Like La Diana, Sakura’s aim was also to “diligently convey to Italy and Europe the greatness of Japanese poetry.” Shimoi took charge, calling himself direttore (director), and relying on old La Diana hands for support. The young Neapolitan poet Elpidio Jenco wrote about Yosano Akiko, and the young composer Vincenzo Davico expressed his appreciation of a tanka poem of hers. Most active was Shimoi himself, now translating excerpts from the novels of Mori Ōgai (1862–1922) and Kunikida Doppo (1871–1908), as well as poems of Higuchi Ichiyō (1872–1896). But he also enlisted new collaborators, most conspicuously Dan Inō, the son of the wealthy industrialist Dan Takuma and later a professor of art history at Tokyo Imperial University, who visited Naples on a study tour to Italy.64

The most striking novelty in Sakura was the turn toward classical literature and folklore. Shimoi himself introduced the oldest collection of Japanese poetry, the eighth-century Manyōshū.65 Dan wrote on the Edo period (1600–1868), including woodblock prints (ukiyoe) and painting. Other articles dealt with comic drama (kyōgen), Buddhist temples, and traditional beliefs. Premodern Japanese houses were described as “full of grace, poetry and dreams.”66 This was a marked a departure from La Diana’s modernism. If in La Diana Shimoi’s aim had been to prove that Japan’s modernity was coeval with that of Italy, in Sakura he wanted to show that a characteristic of Japan since time immemorial was the way in which poetry was present in the everyday life of its citizens in the form of an aesthetics of home and community. In Japan, he contended, “poetry became a supreme spiritual element, a daily practice of life.”67

There was more to this argument than nostalgia. Rather, Shimoi believed that the Japanese spirit inherently tended toward harmony, and that this realization was crucial to overcome the social and cultural conflicts of the 1920s. In Japan, he asserted, even a duel between implacable enemies would end with a reconciliation of the two, “brothers in Poetry.”68 Validating the timeless past of Japanese literature for an uncomfortable present was therefore Shimoi’s goal in Sakura. As he wrote in the introductory issue, he wanted to “uncover, especially, the purity of the Nipponic soul, which is a marvelous and moving human phenomenon, today that the world and human beings are a precise and uniform system of logarithmic tables. To reveal poetry: to reveal man.”69 This discovery, he contended, had a particular meaning for Italians, because they shared the Japanese inclination toward poetry, as they had demonstrated during the war. “The literary sensibility of the most different races becomes parallel,” Shimoi and Jenco had claimed in a publication of these years.70

Shimoi soon became aware that introducing Japan to Italy was more difficult than he had imagined. Money was in short supply and irregular, partly due to his own romantic disdain for the material aspects of life. In late 1920 he quit his post at the Oriental Institute in Naples to dedicate his energies to his cultural project, meaning that he was left without a steady income.71 For some time he received pay from the Japanese Embassy and the Japanese Ministry of Education, but these subsidies were also highly irregular.72 What limited means Shimoi had he spent on books, boasting in 1921 that he was the owner of over three thousand works on Dante.73 More damaging to his ambitions was the fact that Shimoi had overestimated the Italian interest in Japan. By 1920 the brief modernist fascination with Japan that had characterized La Diana was over. Torn between nationalism, Fascism, and socialism, Italians had little time for Japonisme, Myōjō, or its postwar counterparts.

Shimoi came to realize that he had reached a turning point. As Mussolini solidified his rule, he became aware of the growing Japanese interest in Fascism and Mussolini and proceeded to shift his efforts to promoting Italian culture and politics to Japan. As early as September 1922, a month before the March on Rome, Shimoi had introduced a commission of three Japanese parliamentary deputies to the future Duce, the visitors assuring Mussolini that the “liberal public opinion of the Japanese was following with vivid cordiality and interest the Italian Fascist movement.”74 Shimoi took these sorts of remarks as a sign of opportunity. From 1924 to 1927 he traveled between Italy and Japan four times, each time with great media fanfare, to give a “detailed account of Italian current affairs” and culture.75

It was during this period—and moving between Italy and Japan—that Shimoi began to prioritize politics over literature. The Calpis affair, one of his many enterprises during this period, best exemplifies this shift by illustrating Shimoi’s change of alliance from D’Annunzio to Mussolini. A lactose-based drink, Calpis was founded by Mishima Kaiun, an adventurous businessman who is said to have developed the recipe from a drink offered him in Inner Mongolia in the early 1900s. Mishima was an aggressive proponent of marketing techniques, and in June 1924 he attempted to recruit D’Annunzio for a commercial stunt. He charged Shimoi with the task of proposing the idea to D’Annunzio. Mishima wrote that D’Annunzio was uniquely capable to “unify the soul of the [Japanese] people and clarify the goals of our country toward whose reconstruction the people will have to strive.” Japan, he argued, lacked a great man of comparable status. For this reason he asked D’Annunzio to “donate to the youth of Japan a poem of any length and any form” and, possibly, to “accept Japan’s invitation to visit us as a guest of the nation.” He concluded that “Shimoi will personally explain our desires to you.”76 But by this time D’Annunzio, aging and comfortable in his lakeside residence in Gardone, had lost his interest in the long voyage and in Japan. When he was asked by Shimoi for his decision, he replied, tersely and mockingly, that he would not go, but that nonetheless his “heart [was] on top of Mount Fuji and you [would] see it ablaze from afar.”77 Shimoi returned to Tokyo without the much-coveted salute.

Shimoi at his home during a return visit to Japan, ca. 1924. Sitting on his left is his wife, Fuji; standing on his right is Tōyama Mitsuru, an exponent of the Japanese radical Right.

(Photo courtesy of Kuribayashi Machiko, Tokyo.)

But Shimoi was not a man to give up easily. Following an audience with Mussolini in March 1926, he succeeded in getting from the Duce what the Comandante had denied him. Mussolini composed a message addressed to Japan’s youth. He praised Japan’s “high level of civilization” and warned young Japanese to turn away from socialism (“modern demagogic materialism”) and to be true to the “millenarian spirit of [their] race.” Just as Fascism was based on the “conscious acceptance of discipline, hierarchy, and patriotism,” so Japan’s spirit was present in bushido.78

With Calpis taking care of sponsorship, Mussolini’s message reached a vast audience of officials and ordinary Japanese. The message was first delivered with great pomp in Tokyo’s Hibiya Park where, according to the Italian ambassador, a crowd of some ten thousand had gathered, including prestigious political representatives, bureaucrats, and young people whose regular “thundering applause” was matched by a final Fascist salute.79 Shimoi wrote to Mussolini, telling him that the message had drawn widespread attention and gained new admirers. He reported, no doubt with exaggeration, that airplanes dropped “one million” leaflets of the message while three hundred thousand copies of a version of it, including a photograph of Mussolini, were distributed on the ground, and that Calpis had paid for the message to appear in “all daily newspapers of the Empire.” (Although probably an overstatement, Mussolini’s message did appear even in a newsletter of a youth organization in rural Akita prefecture.)80 The organizing committee was composed of three respectable Meiji personalities: entrepreneur Shibusawa Eiichi, politician and bureaucrat Gotō Shinpei, and educator Sawayanagi Masatarō. They wrote to Mussolini, hailing the event as a way to “bring back to the righteous path those youth who had been led astray” and expressing their gratitude for the “immense fervor and formidable [spiritual] revival that [Mussolini’s] message provoked in Japan’s youth.”81

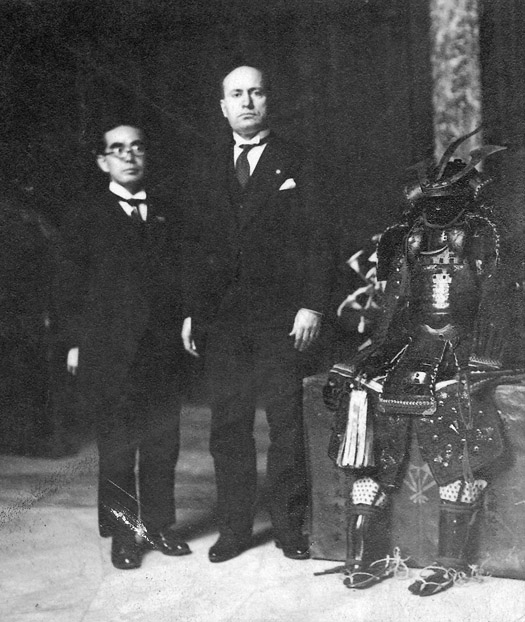

Shimoi Harukichi presenting Mussolini with a samurai armor, 1926.

(Photo courtesy of Kuribayashi Machiko, Tokyo.)

From Shimoi’s point of view, the Calpis affair had been a success. Obscure when he left Tokyo in 1915, by the mid-1920s he was recognized and readily associated with Italy, Fascism, and Mussolini.82 His passion for Italian culture, extending from Dante to D’Annunzio, had ended in an embrace of the Fascist politics of Mussolini and was pursued in the brash, indefatigable manner characteristic of someone who grew up as an ambitious late-Meiji youth. D’Annunzio and Mussolini had a profound effect on him. Shimoi had learned from them how to utilize modern techniques of mass communication, which he put to good use, as demonstrated in his organization of the Hibiya event. His capacity to straddle aesthetics and spectacle, high culture and mass politics set him aside from other nationalists.83 He saw no contradiction between his work as a professore of Italian culture and his political life as an activist for Fascism. On the contrary, Shimoi was convinced that only by linking culture and politics in new ways could Japan’s own resurgence be brought to full fruition.

Paedagocis: Youth and the Myth of World War I

“Japan’s situation is getting worse day by day, with all kinds of problems resembling exactly those of Italy ten years ago. To know the road taken by Italy is the best guidance to think about the road that Japan ought to take.”84 Shimoi expressed these feelings in 1926, in Taisenchū no Itaria (Italy during the Great War, 1926), the work that best exemplified his program of cultural and social reform for Japan in the 1920s. He read the conflicts he found in Japan through the lens of his experiences in Italy and believed that the response that Italians had devised could stimulate a Japanese resurgence. Nevertheless, it was not his intention to replicate Italian Fascism. Rather, he had a more specific goal in mind—namely, to mobilize Japanese youth on behalf of the nation. Mobilization was the thread that ran through his interpretation of Italy’s “second Renaissance.” What La Diana, D’Annunzio, and Fascism had in common for Shimoi was the call on young men and women to set aside their differences by stirring them to unite for their country. He felt that no one was better qualified to teach these lessons than him. In this way Taisenchū no Itaria reveals how Shimoi’s mindset as a conservative Meiji educator, which was based on the principles of obedience and discipline, had merged with the aesthetics of Fascism that he had embraced in Italy after World War I, which called for rebellion, violence, and death.

Italian Fascism saw itself as a youthful movement that would rejuvenate national politics and bring about social order.85 Shimoi could relate well to this discourse. Since the early 1900s conservative critics had alerted Japanese readers to a morally decadent and socially destitute youth—what one of them, the nationalist journalist Tokutomi Sohō, later called “colorless youth” [mushoku seinen].86 In 1920s Japan, as elsewhere, the social landscape of youth had grown ever more complex. After the economic expansion during World War I, rural youngsters migrated in large numbers to Japan’s major industrial cities. In places such as Tokyo and Osaka these youth became part of the masses that made up the country’s working class, unemployed and, sometimes, petty criminals.87 Educated urban youth often embraced socialism, feminism, or consumerism, causing disquiet among commentators like Sohō, who argued that youth had to be taught the ideal of linking individual interest to that of the state. As Sohō put it, “Without ideals [risō], there is no ambition; without ambition there is no self-denial [kokki], no endeavor [doryoku] and one easily ends in self-abandonment [jibōjiki].”88 Mussolini and Fascism, it seemed to Shimoi, had overcome these modern evils by organizing Italian youth around the time-honored values of the nation.

Taisenchū contained Shimoi’s strategy to mobilize Japanese youth. The book was a mythic account of World War I characterized by a narrative of heroism and sacrifice that linked the patriotic fervor of the prewar years to the spirit that was born on the battlefields and continued in peacetime under Fascism.89 A project that bears the hallmark of Shimoi’s expertise in children’s tales, the book outlines the main events and protagonists of Italy’s war as a moral story directed at a young readership. While it revives the themes in Shimoi’s earlier work, The Italian War (1919), Taisenchū presents the war as an aesthetic adventure that is character building and formative. “Poetry is dead,” remarked a French soldier in 1917.90 Shimoi could not have disagreed more, for, in his view, it was alive and well in the politics of Fascism.

George Mosse has argued that Italy was at the forefront in the wider transformation of the relationship between poetry and politics around the time of World War I.91 Taishenchū illustrates this point not only in Shimoi’s move from D’Annunzio to Mussolini but also in his contention that ordinary Italians—especially young men, but also women and children—had rediscovered poetry in their everyday lives by fighting in World War I. He glorified Nazario Sauro and Cesare Battisti, irredentists who were executed by the Austrians for their pro-Italian activities; Enrico Toti, the maimed “one-legged” hero who had made a name for himself by riding his bicycle to Lapland before dying as a volunteer in the trenches; Luigi Rizzo, the naval officer who sank the Austro-Hungarian battleship Szent István; Francesco Baracca, a virtuoso air-force pilot killed in action; and E. A. Mario, the Neapolitan writer, poet, and folk musician who after the war composed the patriotic song “The Legend of the Piave.” Shimoi was fond of portraying his affection for these soldiers as well as the peasants and women he met near the frontlines, for whom, he argued, war was at the same time art and materiality.92 On one side, there was the harshness of daily life—hunger, cold, and death—and on the other, the production of poetic life. All Italians were poets, he explained. On one occasion he caught a group of soldiers in the trenches reading the nineteenth-century poet Giovanni Pascoli as bombs flew over their heads. Elsewhere, he recounted the story of one soldier who, in spite of his minimal education, had become “an incandescent poet” at the front, always stirring up the emotions of the men around him.93

In a European context, Taisenchū may have seemed a banal example of a right-wing memoir of World War I. But in a country that had not known the trenches or total mobilization, and where firsthand accounts of the conflict were few, the book stood out. Shimoi’s melodramatic and gripping style, aided by over fifty photographs, struck a chord with young Japanese. During the 1920s the market for popular literature boomed, and it is telling that between 1925 and 1927 Shimoi published eight books with some of the most representative presses of this period.94 Fassho undō (The Fascist Movement) was published by Minyūsha (1925), the house founded by the conservative critic and journalist Tokutomi Sohō, who by then had come to display a keen interest in Fascism and Shimoi. Mussorini no shishiku (Mussolini’s Lion Roar) appeared as a special edition of Kōdansha’s King (1929), the main magazine of mass culture in the second half of the 1920s. (In March 1930 the publishers were still advertising the book, then in its twenty-third edition.)95 Shimoi claimed that his Gyorai no se ni matagarite (Riding on the Back of a Torpedo, 1926), a book on Italian special squads, was “chosen as a reading for the empress and the prince regent, a distinction that is given only rarely and only to books of national interest.”96

Although all these publications replicated Shimoi’s personal myth of World War I, some went further in presenting in great detail the way in which, according to its author, Fascism had changed Italians and what Japanese could learn from it. Under Mussolini’s rule, young Italians spontaneously respected the “ancestral land,” unlike Japanese youth, who did so only because they were told to in school.97 Italians had become efficient. They no longer engaged in long, formulaic greetings like the Japanese but jumped to their feet and raised their arms in a Roman salute, exclaiming “To us!”(A noi)—a sign, Shimoi felt, of their willingness to work hard, and a salute that ought to be adopted by Japanese, as “Wareware ni” sounded equally good.98 Italians had become champions of “manliness” (otokorashiishugi); Japanese were stuck with an effeminate obsession with “safety first” (anzen daiichi).99 Italian women were good wives, wise mothers, and understood that the home (katei) was the “way” (michi) of the woman. Their Japanese counterparts lacked these morals. They acted like “Americans, copying their women’s movement, and, advocating women’s suffrage, they go outside the house at will strolling around, they make speeches in their shrill voices, hang around in that flippant manner—and they call themselves ‘culture women’…I hate these women.”100 It is difficult to gauge the effect of Shimoi’s books on his readers, but, at least as far as one editor was concerned, Shimoi’s work demonstrated the close resemblance between the sentiments of Italians and Japanese, and had “penetrated particularly the hearts of our youth and urged the awakening and arousal of their spirit.”101

In addition to his publications, Shimoi used another strategy to mobilize Japanese along the lines of Fascism. Resorting to the oratorical skills he had learned from D’Annunzio and Mussolini, he became a grassroots activist. Traveling through the entire archipelago, he boasted that he had given “more than four hundred speeches” to workers, peasants, ex-military, and students, and made a point of mentioning that each one lasted on average three and a half hours.102 In many of these speeches he attacked the labor movements and their requests for shorter working hours. In Italy, he pontificated, there were no debates about the eight-hour day. Mussolini had done away with this simplistic socialist conception of the limitation of the worker’s time. The Duce himself dedicated as little time as possible to leisure or meals, working some twenty hours a day. “If one works thinking of one’s dignity, work is not at all a hardship—it becomes a pleasure. It is possible to work eight hours, nay ten hours, even twelve hours.”103 Shimoi earned himself a reputation as a strikebreaker. On one occasion, the chairman of the Japanese Communist Party, Sano Manabu, referred to an incident at Ashio’s copper mines when management had called on Shimoi to dissuade workers from forming a union. Sano added that “when [Shimoi] started his speech, a threatening crowd of workers chased him off the premises.”104

Shimoi’s forays into other organizations whose membership was composed mainly of young men offer further evidence of the extent of his work and goals in the mid-1920s. He forged connections with the military. According to the Italian ambassador, in these years Shimoi received the support of the army and navy ministries, although it is not clear in what form.105 He also founded a “patriotic movement,” the Kōkoku seinentō (Imperial Country Youth Party). To train its young members, he followed musters he had learned in Italy. His goal, as he wrote to Mussolini, was to counter “the penetration of Russian communism in the industrial and agricultural centers, as it leads to painful agrarian conflicts, strikes, class conflict…under arrogant red organizations.”106 While his movement was short-lived, the significance of this experiment lies in what Shimoi had in mind. He explained that it was based on the Fascist type but, crucially, was “adapted to the national characteristics of Japan, that is, it is based on the sentiment of the ancestral land unified through the monarchy.” In other words, in Japan political and social reform was centered on the emperor, who “was and must be forever the center of national solidarity.”107

Shimoi Harukichi at the height of his fame, ca. 1927. Among the bystanders are the right-wing patron Tōyama Mitsuru and the conservative journalist Tokutomi Sohō, standing next to Italian embassy officials. The event was sponsored by Yebisu Beer.

(Photo courtesy of Kuribayashi Machiko, Tokyo.)

Black Shirts, White Tigers: The Byakkōtai Affair

On December 6, 1928, the provincial town of Aizu Wakamatsu, three hundred kilometers northeast of Tokyo, celebrated the arrival of a Roman column sent to it as a gift of friendship by Benito Mussolini. The event commemorated the “white tigers” (byakkōtai), a group of young Aizu warriors. They had fought on the losing side during the Bōshin War of 1868, the conflict between the newly established government under Emperor Meiji and the shogunate, with which the Aizu Domain was allied. After imperial troops defeated their clan’s armies, the young patriots committed suicide rather than fall prisoners to the enemy. What sparked the Duce’s interest in the episode was a casual reference by Shimoi. Mussolini, it seems, expressed admiration for the byakkōtai and made a vague promise that he would back up his sentiments with a concrete gesture.108 Rumors spread, probably circulated by Shimoi, provoking great excitement among Aizu notables, who inflated the story of the Italian leader’s interest into a matter of national importance. The byakkōtai affair turned into a diplomatic problem between Japan and Italy, but it also became an opportunity for Japanese to revisit patriotically a divisive and, until then, unresolved, incident in their recent history.

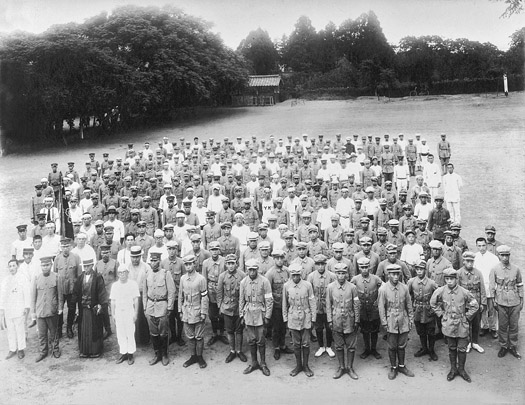

Shimoi at the head of a youth movement, unnamed but possibly the Kōkoku Seinentō, the short-lived group he had founded in the mid-1920s. Such groups became more common in the late 1920s and 1930s, but it is likely that Shimoi drew inspiration from Fascist youth organizations such as the Balilla or the Fasci Giovanili di Combattimento. Shimoi, dressed in white, is third from the left in the front row, ca. 1926.

(Photo courtesy of Kuribayashi Machiko, Tokyo.)

Although publicized by Shimoi, the driving force of the byakkōtai affair was a coterie of influential bureaucrats from Aizu. Desirous of the honor and recognition that a gift from Mussolini would bring, they pressured government officials into persuading the Fascist regime to live up to its leader’s word. In February 1928 Baron Yamakawa Kenjirō, a local and former head of Tokyo Imperial University, urged Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi to intervene so that the celebrations would be held. Preparations had already started in Aizu, Yamakawa informed him, but there were as yet no signs of the monument; and “Shimoi is nowhere to be found.”109 Swayed by this appeal, Tanaka sent his deputy to persuade the Italians to complete the work. If shipping a monument was not possible, the diplomat asked, would Mussolini at least consider sending a “solemn message.”110 Eventually, the Italians gave their approval. After some quibbles over the text of the engraving, the 8.35 meters high, 25-ton column, dug out from the Roman Forum, finally left Naples in October 1928.111

In the hands of Japanese government officials the byakkōtai commemoration became a major national event. A high-profile committee provided the pomp and circumstance for the inauguration of Mussolini’s gift to Aizu and Japan. Tanaka Giichi was himself a member, as were Shidehara Kijurō, the foreign minister, and Matsudaira Tsuneo, the ambassador to Britain and an Aizu native. Baron Ōkura Kishichirō, head of the Ōkura conglomerate, represented industry; the military contributed by sending the emperor’s aide-de-camp; and to give the committee a touch of aristocratic gravitas Prince Konoe Fumimaro was the committee’s president, while Prince Takamatsu, the emperor’s third brother, lent the celebration his august patronage. It was the “first time an imperial prince [had] assumed such a role,” the Italian ambassador, Pompeo Aloisi, informed his superiors in Rome, assuring them that this had to be considered “a special act of deference from the emperor” to Mussolini.112

The unveiling of the antique column, adorned by the regime with its two most distinctive symbols, an eagle and two fasces, had three major consequences. First, cultural effusions over the byakkōtai promoted a diplomatic rapprochement between Japan and Italy. In his speech, Konoe articulated his conviction that “this monument, besides enlivening a constant inspiration of the civil virtues of the nation, will also be a spiritual symbol and an act that strengthens ever more the friendship between Japan and Italy.”113 It was a nicety that was not altogether out of place. On July 12, 1929, Shidehara Kijurō met Aloisi, remarking that “on various international questions…the Italian and Japanese governments, which have so much similarity in their foreign policies, keep friendly relations.”114 Prince Takamatsu echoed the minister’s diplomatic sentiments. After a tour of duty to London in November 1929, he made it a point to visit Rome for an audience with Mussolini to express his gratitude for the gift of the Roman column.115 And, the following year, Ōkura Kishichirō sponsored an important exhibition of Japanese modern art in Rome.

The Roman column sent to Aizu-Wakamatsu by Mussolini in 1928. At its lower end are the fasces, symbols of Fascism, which were removed during the Allied Occupation (1945–1952).

(Photo courtesy of ASMAE.)

The event had another effect. Thanks to its high profile and broad coverage in the press and newsreels, Fascism and Mussolini extended their reputation in Japan beyond the major metropolitan centers. One Japanese official commented that the news of Mussolini’s column was “spread by newspapers, and not just in the area of Aizu, but in the whole country, and, in particular, it has raised interest and expectations among young people.”116 Indeed, people flocked to the occasion in large numbers. When his train was nearing Aizu, Aloisi was stunned to see that, despite it being six o’clock in the morning, there were “not only all civilian and military authorities of the province, but the entire population who, for about six kilometers was shouting ‘alalà’ [a Fascist salute] as I passed to go to the hotel.” The town was adorned with Italian flags—the first time a foreign flag had been flown there, he asserted. Iimoriyama, the hill designated as the site for the monument, would become one of Japan’s “most regularly visited places of pilgrimage.”117

Finally, the byakkōtai affair offered a chance to bring Aizu’s uncomfortable past into national history. In the sixty years since the end of the Bōshin war the “white tigers,” having fought against the emperor’s army, had remained “enemies of the court” (chōteki) in official discourse. To be sure, since 1868 Aizu locals had gradually managed to enter the higher ranks of officialdom. Yamakawa and Matsudaira were two examples.118 But the byakkōtai was not granted a place in the complex of national myths. The 1928 event made this possible. With the presence of representatives of all major organs of the state, the commemoration of the byakkōtai through the Roman column amounted to an implicit acknowledgment of the “white tigers” as national heroes. Konoe Fumimaro was unwittingly touching on the hidden meaning of the event when he commented that “this rejoicing and satisfaction should not be confined to the members of the byakkōtai but be enjoyed and felt by the nation as a whole because the spirit of the chivalry of our Japan was upheld abroad by the premier of Italy.”119 In short, Fascist recognition of the byakkōtai strengthened Japanese national unity.

The byakkōtai affair marked the apex of Shimoi’s career as Fascism’s impresario in Japan. His role in the event was limited to bringing the “white tigers” to the attention of Mussolini and was not publicly acknowledged, but he no doubt took it as a validation of his convictions about the spiritual bonds between Japan and Italy. For him, the story of the byakkōtai proved that the two countries could mutually reinforce each other. The byakkōtai had moved the Duce, convincing him to express his admiration for the young warriors in the form of a Roman—and Fascist—column. This symbol provoked great interest in Japan, to the point that it allowed Japanese to overcome a past history of division and conflict. Ultimately, it appeared to Shimoi, the event led to the kind of national mobilization that he had been advocating. By emphasizing youth, both as the subject of commemoration and the object of mobilization, he believed that the byakkōtai affair vindicated the pedagogical project he had devised in late Meiji.

And yet the byakkōtai affair also terminated Shimoi’s vision of social and cultural reform based on Italo-Japanese intimacy. His latest—and boldest—attempt to mediate between the two countries interfered with the diplomacy of two states, which led to animosity toward him at all levels. The Japanese ambassador in Rome informed his foreign ministry that Shimoi’s “deceptions” had “touched on the honor of Mussolini.” His superior agreed, inflamed at Shimoi’s “profiteering” and the “great trouble” he had caused.120 In Italy, Antonio Beltramelli, a biographer of Mussolini and once a faithful friend, reported that it had become clear to him that Shimoi was a fraud, that he had been investigated by the Neapolitan police, and that he had been “a cocaine dealer.”121

Events surrounding the byakkōtai celebrations ushered in a new phase in Japan’s relation with Fascism. The relatively spontaneous eruption of the affair signified not only that, by 1928, Japanese had acquired a great deal of familiarity with Italian Fascism but also that they no longer needed Shimoi’s mediation. From the early 1920s Shimoi had perhaps done more than anyone else to popularize Italian Fascism, commodifying its exponents—D’Annunzio and Mussolini—and rephrasing its ideology into a language of patriotism that could be readily understood by a mass Japanese audience. In this sense, Shimoi’s fascism was produced neither in Italy, nor in Japan, but in both contexts. If the escalating interest in Fascism was partly Shimoi’s success, as he had helped to create it, it also caused him a setback, for he could not control it. As he searched for new roles, a wider public turned to scrutinize Fascism, starting with its leader, Benito Mussolini.