2

THE MUSSOLINI BOOM, 1928–1931

Andrea: Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero.

Galileo: No, Andrea: Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.

—Berthold Brecht, Life of Galileo, 1938

“Among today’s world leaders, whom do you like best?” a newspaper asked Japanese in a national survey in 1927. The readers’ response left no doubt: Benito Mussolini, the Italian dictator and Duce of Fascism.1 Their answer was confirmed by a veritable boom around Mussolini in the late 1920s. Featured in theater plays, biographies, commercial advertisements, and films, he emerged as a popular celebrity as well as a political leader much discussed by the Japanese public. To be sure, in this period Mussolini was making headlines around the world. In such liberal countries as France, the United States, and Great Britain journalists and intellectuals found much to admire in this man, whom they often compared with Napoleon, Caesar, or Cromwell. As a Columbia Productions poster later put it, Mussolini “might be the answer to America’s needs.”2 But in Japan, perhaps more than elsewhere, the timing of Mussolini’s popularity is noteworthy. The year 1928, when the interest in him peaked, coincided with Japan’s first election held under universal male suffrage. How can we explain the thirst for knowledge about the life and deeds of a dictator at a time when Japan had reached one of the liberal pinnacles of Taishō democracy? For many contemporaries this was no paradox.

In the second half of the 1920s, politicians, journalists, and critics began to argue that liberalism had reached an impasse. Progressive reformers who had once supported such liberal ideals as party cabinets, freedom of expression, and meritocracy as a way to curb the power of unelected institutions—the bureaucracy, the elder statesmen (genrō), or the military—came to the conclusion that a decade of liberal politics had done little to change the status quo.3 They saw the Peace Preservation Law (1925) and the institutionalization of the two major political parties, the Seiyūkai and the Minseitō, as symptoms that the government remained in the hands of established elites who repressed the will of the people rather than representing it. Conversely, conservatives criticized the liberal reforms, contending that these principles had led to a moral selfishness that caused the people, whom they principally understood as “imperial subjects,” to disregard the higher ideals of the state. Though at loggerheads over the value of liberalism, both groups agreed that the underlying problem was the individual’s role in modern mass society. For reformists, liberalism had failed to develop a “new consciousness” that would have stirred the individual into seeking a more popular government; for conservatives, liberalism had enabled individuals to challenge the institutions of the state and their legitimate place in a hierarchical arrangement of power.4

The preoccupation with Mussolini outside the circles of the radical Right grew as a result of the Duce’s capacity to straddle both liberal and conservative ideals of the individual. Some Japanese with a liberal bent were drawn to Mussolini because he had displaced the entrenched elites thanks to his skill to mobilize the people, an endeavor, they pointed out, that Japanese politicians were either reluctant to undertake or incapable of replicating. Mussolini’s populism, his background as a journalist, and his gifts in oratory, led them to believe that he was the opposite of those whom Tokutomi Sohō, the nationalist commentator, vilified as “specialized politicians,” functionaries who served state and emperor but lacked any connection to the people.5 Conservatives, anxious about raison d’état, commended Mussolini’s determination to repress the Left and curtail individual freedoms in order to reinforce the existing social order and the prerogatives of the state. The Duce appeared to be a talented statesman who swayed Italians into obedience by inculcating in them a love of nation and state. Mussolini, then, appealed not so much as a despot, but as a man who had developed cultural and political strategies that could be appropriated—on the side of conservatives, to curtail liberalism and, on the side of liberals, to revamp a liberal democracy that was in crisis.

In this way, the debate about Mussolini spoke to the quest for an individual capable of healing the rifts in modern mass society by forging consent between rulers and ruled.6 In other words, it was a discourse about political and cultural leadership. Indeed, writers and politicians of late Taishō and early Shōwa displayed an acute interest in the lives of leaders past and present, discussing them in terms of “great men” (ijin), the character of a “genius” (tensai), or the attributes of a “hero” (eiyū). To some extent, they longed for a talented, hard-nosed politician who would rise above the perceived mediocrity of Japan’s ruling class. In 1928, for example, Tsurumi Yūsuke, an acclaimed Anglophile author, politician, and orator, published On the Hoped-for Hero (Eiyū taibō-ron), in which he lyrically lamented that only a great man could put an end to his country’s stagnation: “Genius, arise! Hero, arise!”7 But often leadership was thought of as an aspect that had to be cultivated in ordinary Japanese. Educators, in particular, worried about the leveling effect of modern mass society and sought in the lives of leaders evidence that all Japanese could achieve great things, even if these accomplishments belonged to the general sphere of their everyday lives. In an age of consumerism and materialist ideologies, they argued, Japanese could excel in moral leadership, such as upholding the value of the family or the sanctity of the state.

Mussolini had a broad appeal because he seemed to possess both extraordinary and ordinary features of modern leadership. Max Weber famously argued that these qualities were merged in a “charismatic leader,” but this type of individual was hardly what Japanese political and moral commentators were looking for.8 Rather, they believed that Mussolini’s ordinariness—his lower-middle-class background and his manliness—should inspire Japan’s elites to be closer to the people; and that, conversely, his extraordinary talents as a strong statesman were capable of arousing in the people the sentiment that heroism was within everyone’s reach.

Much about Mussolini was, of course, a myth, carefully crafted in Rome by the regime, reinforced by the Duce himself, and seconded by admirers at home and abroad.9 Thus the significance of the Mussolini boom lies in the fact that Japanese writers, ideologues, educators, and politicians participated in the production of the global myth of Mussolini even as they debated the Duce in the context of the political and cultural anxieties of Japan. But this does not mean they accepted the verities of Mussolini uncritically. Quite the contrary was the case. Even as they evinced a range of interests in the figure of Mussolini, they appropriated the facets of his character selectively, often balancing his virtues with a wide scope of criticism that was absent in Shimoi Harukichi. Still, sharing with Mussolini a desire to rebuild national communities, liberals and conservatives operated in a gray area, a space that could accommodate Fascist leadership strategies in order to strengthen the bond between individuals and the state at a time when liberalism was in crisis.

An Italian Hero

Several liberal and conservative commentators were deeply ambivalent about Mussolini. A leader, they contended, had to be a revelation of the national past, not a revolution coming from the global present, and Mussolini served the reality and needs of Italy. Tsurumi Yūsuke made this point when he stated that a hero was organically connected to his people, who would spontaneously follow him because he was a “comprehensive leader” (sōgō shidōsha), one who embodied all the qualities of the nation. Optimistically, he added that, because “the heroic spurt of blood that brought about the Meiji Restoration [in the 1860s] is still throbbing in the veins of the Japanese nation [minzoku],” they would naturally produce an indigenous leader without the need to rely on foreign models.10 Progressive spokesmen like Tsurumi were among Mussolini’s fiercest critics, and yet, it is important to emphasize, their skepticism reflected not so much an uncompromising defense of democratic politics as considerations of national characteristics.

The idea that Mussolini was good for the Italians but bad for everyone else betrayed two conflicting tendencies of liberal thought about the Duce. Steeped in the tastes of Anglo-American liberalism, the Japanese liberal intelligentsia also shared its racist stereotypes of Latin peoples, among which Italy was assessed as a particularly backward country. Italians were often perceived as lazy, dirty, and unrefined. Indeed, Tsurumi surmised, for Italians life was a very “practical” (genjitsuteki) thing. Contrary to the Germans’ “abstract conception of the world,” Italians thought of “eating, drinking, singing, and loving.” Their nature was such that

they cannot think with their own heads. Therefore when an extraordinary man thinks in their stead, they accept him unreservedly. They do not live in an abstract world, but in a pragmatic one. So they logically acknowledge that a lion is stronger than a cat.…If a Caesar emerges they are conscious that Caesar is greater than ordinary people. If a Michelangelo emerges, they recognize that Michelangelo’s art is finer than that of the common run of men. If a Mussolini emerges, they will recognize immediately that he is greater than an Antonio or a Giovanni.

For this reason, Italians gave birth to such a figure because they have “no opinion, no education, and no strong individual consciousness…they are not fit for democracy.”11

Backwardness, however, also meant that the primordial instincts of Italians were more or less intact. And “élan vital [seimei no yakudō]” was a virtue much praised by Tsurumi. He admitted that Italians possessed the “bursting vital energy characteristic of primitive people,” a quality that made them “remarkably young” compared to their senescing European neighbors (who, Tsurumi observed, had at the very least “reached middle age”). He admired Italians’ bravery and their readiness to spring into action. “They are not like the Swiss, who save every penny, breeding cows in their pastures and trying to make some money with milk. With their adventurous hearts, Italians leap into danger.”12

Linking the instincts of the nation with those of the individual was a Darwinian association that was widespread among Taishō liberals, many of whom argued that Mussolini expressed the Italian collective instinct.13 Nitobe Inazō, a Christian author, diplomat, and politician as well as mentor to Tsurumi, went so far as to remark that Mussolini represented a turning point in Italian history. After he visited Italy during the early years of Fascism, it seemed to him that he had witnessed “verily the beginning of the Italian revolution, the second stage of the French revolution.” He left Italy with only one regret, “not having had the chance to meet this hero [gōketsu],” Mussolini.14 For Nitobe, the Duce represented the dead past of Italy at the same time as he embodied the vital impulses necessary for this nation to thrive.

The association of Mussolini with Italy could lead to another critical perspective. Mussolini was an extremist, the argument ran, because he assigned too much weight to either state authority or popular instinct, causing excesses that might have been necessary in Italy but were undesirable in Japan. Liberals feared that Mussolini commanded too much state power. “Mussolini might be great [erai], but in that they accept his repression, Italian citizens prove that they are unable to take care of their own lives and that they can hardly be considered honorable citizens.” This was the assessment of Nakano Seigō, a journalist and aspiring politician better known for his outspoken sympathies for Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in the mid-1930s but who, at this time, advocated representative democracy.15 Nakano’s comments were really directed at the increasingly authoritarian politics of General Tanaka Giichi, prime minister from 1927 to 1929. Although Nakano was no backer of the Japanese Left, he criticized the viciously anticommunist Tanaka Giichi and his home minister, Suzuki Kisaburō, who in 1928 had ordered a crackdown on the Japanese Communist Party. “Suzuki,” Nakano held, “reeks of Mussolinian violence [bōryokushugi].” The phenomenon of Mussolini, Nakano claimed, had to be understood in the context of the inferior moral development of Italians. By trying to imitate him, Tanaka and Suzuki “let themselves be misled by the trend of a small-sized, simple and convenient Mussolini, just like the fad for small-sized taxis [entaku-kei].” Japanese, Nakano was quite sure, did not deserve a Mussolinian treatment. “Our citizens, as one could see in the election some time ago, have a lot of common sense. They are not a baseless [kudaranai] people. They will not let themselves be ruled either by the tip of the brush of Marxism or by Mussolini.”16

If liberal politicians connected Mussolini to an expansion of state repression, conservatives worried that he was a figure who undermined the state’s authority. Although they welcomed the Duce’s crushing of the Left, they found it intolerable that a crowd of petty-bourgeois parvenus like Mussolini and his followers could displace existing political elites and take over the high offices of the state. Ultimately, they were terrified that an ordinary man could impinge on the prerogatives of the sovereign. “Will Mussolini become a monarch?” asked a seasoned commentator of international affairs, Inahara Katsuji. The journalist believed that Mussolini had created the Fascist Grand Council, a new constitutional organ, as a way to establish a Machiavellian dictatorship. Just like Lenin, Mussolini “sees ends, not means.”17 In such a situation, Inahara continued, “Mussolini would supervise Mussolini, that is, a farce.”18 The problem, however, was not so much that he escaped popular control, but that his institutionalization would cause the “meaning of the existence of the monarch himself [to] become extremely shallow.”19

The relationship between a figure like Mussolini and a monarch was particularly sensitive in Japan because it became embroiled in an existing controversy over the place of the emperor in the Japanese state. The so-called organ theory debate originated in differing scholarly interpretations of the Meiji constitution but by the late 1920s had spilled over into more heated public disputes. One side, led by the scholar Minobe Tatsukichi, argued that the emperor was merely an organ of the state; Minobe’s opponents, especially Hozumi Yatsuka and Uesugi Shinkichi, professed that the emperor transcended the state and that, therefore, he was not accountable to the people. In February 1928, no doubt as a response to the popularity of Mussolini, Uesugi published an article on the Duce in the current affairs journal Chūō kōron. “On Mussolini, Enemy of Reason and Justice” rebuked Mussolini and those Japanese who, according to its author, sympathized with him. For Uesugi, Mussolini was a “monster dictator” whose politics contradicted the Japanese “kingly way” (ōdō), which was based on the “love and justice” that emanated from the emperor. He did not worry about Mussolini’s repression of people’s democratic rights, but that he was the outcome of the masses possessing too many rights and aspirations in the first place. Parliamentary democracy gave an unnecessary voice to the people, as was the case in Europe, whose “five-hundred million idiots [baka]” were trapped in “a great chaos of thought.” Japanese needed neither democracy nor Mussolini, but the emperor’s benevolent rule, which embodied the “idea of virtue, develop[ed] civilization, construct[ed] the state in eternity, and…perfect[ed] the people’s quality as human beings [jinkaku].”20 Ultimately, the problem with Mussolini was that, although his attempt to harmonize the relationship between the people and the state was laudable, he failed to strike the right balance, causing variously populist excesses that desecrated state authority or, conversely, government repression at the expense of the people.

A Modern Hero

The critical view of Mussolini coexisted with a more positive interpretation granting that the Duce possessed certain qualities that Japanese politicians of the 1920s lacked. In particular, in these years liberal “reformists,” backed by large swaths of public opinion, attacked the political class on two accounts.21 First, they argued that Japanese leaders, in their embrace of Wilsonian internationalism, had given proof of their unwillingness to stand up for the national interest. They had sacrificed Japan’s rightful colonial interests in Asia, and in particular in China, in order to develop a foreign policy that was too conciliatory with the West. Second, politicians were accused of being corrupt and removed from ordinary people. As a critic later summed it up, Japanese politicians had a poor hand at being popular, because “they do not know the techniques.”22 What intrigued these critics was Mussolini’s capacity to win popular support despite being a dictator. The search for Mussolini’s universal lessons meant not only that he had to be partly removed from his national context; it also meant that, in order to appropriate some of his strategies, Japanese depoliticized him, separating him from the ideology of Fascism.

Echoing the views of their German contemporary, the conservative legal scholar Carl Schmitt, Japanese critics of parliamentary democracy lamented the absence of a figure capable of making decisions. As early as 1923, the vice minister of the army General Ugaki Kazushige praised that “extraordinary man [kaiketsu], Mussolini” for having formed a resolute political leadership.23 Critics, liberal and conservative alike, felt that the shortcomings of Japanese leaders were particularly acute when it came to foreign policy.24 They chastised party cabinets, whether from the Seiyūkai or Minseitō, for being indecisive and bent on compromise for the sake of the politics of internationalism promoted by the League of Nations and the Western powers. The Washington Conference of 1922, in which Japan agreed to limit the size of its naval armaments, was one case that caused great domestic uproar. Even more sensitive with the population was the government’s open-door policy in China, and especially in North China and Manchuria, areas that many in the military, but also in the government, had earmarked as Japanese spheres of interest.25

With these concerns in mind, Japanese advocates of a “strong foreign policy” (kyōko gaikō) praised the “iron man” (tetsuwan) Mussolini and his stance on foreign affairs. In a two-part article on Italian politics, the Asahi newspaper journalist Maida Minoru (1878–?), a veteran Europe correspondent, commented on Mussolini’s firm grip on his country’s foreign policy. He emphasized the Duce’s military intervention during the 1923 Corfu incident, when Mussolini had ordered a naval and aerial bombardment of the Greek island after the killing of an Italian general and then refused to collaborate with the League. Maida hailed it a success for the Duce, noting that determination in foreign policy helped him to remain popular at home and gain respect abroad.26

Another journalist interested in Mussolini’s approach to foreign policy was the Osaka Mainichi correspondent, Nakahira Akira, who found in the Duce a leader who dared to challenge established norms and stand up to the Great Powers. Admitting that Mussolini’s territorial ambitions in North Africa, Ethiopia, and the Balkans destabilized Europe, he nevertheless legitimized Mussolini’s ambitions. Italy, Nakahira argued, was oppressed by the international status quo sanctioned by the League of Nations. Its major powers, France and Britain, obstructed Italian colonial expansion as a solution to the country’s lack of resources and its excess population. According to Nakahira, because Japan faced the same problems, “one must learn from the Fascist attitude of facing the world and majestically stress the clear consciousness of one’s needs.…Just like Italy, our country should call out its demands on the Asian continent.”27

Mussolini’s attitude in foreign affairs was not the only aspect of his leadership to evoke discussion. Journalists wrote with admiration about Mussolini because of his political style and the techniques he developed to rule Italians. In the 1920s the Fascist regime developed a sophisticated aesthetic apparatus around the person of Mussolini with the intent to promote what is often called a “cult of personality.” Through photographs, films, and biographies the regime attempted to create a mythic image of the dictator as a “new man” with exceptional qualities, emphasizing his energy and ability to dominate, and thus to unify, the people.28

Several pundits yielded to this image of the Duce. In the context of the perceived mediocrity of Japan’s political class, they contrasted Mussolini to Japanese politicians who, in their view, indulged in long-winded discussions that failed to inspire ordinary Japanese. In 1924, the political scientist Yoshida Yakuni, a scholar of Machiavelli, witnessed a speech of Mussolini’s and was struck by his rhetoric. “To imagine what Mussolini’s speech was like, one should think that it was just like his looks…his voice, reverberating like a bell, could be heard from afar…powerful and abounding with energy, not in the slightest does his voice provoke a feeling of ennui in the listener.”29 Nagai Ryūtarō, an exponent of the liberal reformists and, in the 1930s, the holder of several cabinet posts, hailed Mussolini’s oratory as an example of a patriotic leader’s devotion to nation and state.30 So impressed was Nagai by the Duce’s oratory that in 1927 he translated Mussolini’s maiden speech. Nagai argued that Japanese misunderstood Mussolini, a “giant” (kyojin) of the contemporary world, when they called him an “arrogant” leader. In his view, the Duce’s “arrogance [was] not due to haughtiness but, on the contrary, to his ardor burning for emperor and country.” Having offered to the sovereign “his passionate efforts and his intention to achieve their perfection,” Mussolini encapsulated the highest principles of government.31 His dedication, Nagai continued, should be a lesson for the Japanese. “In the present day, Japan awaits the emergence of an arrogant great politician, just like Mussolini, fearing the heavens yet not fearing man, who can carry out a great, resolute revival of the state.”32

Mussolini developed another strategy of rule that fascinated Japanese: personal audiences with the leader. Receiving visitors, Italians and foreigners alike, occupied a large part of Mussolini’s working day and was an integral part of his regime. He used audiences for paternalistic exchanges of favors, but also as a symbolic device that represented the union of the people and their leader, as if to emphasize that one man alone could represent ordinary Italians more effectively than parliament. The staging of the audiences was closely regulated by his secretariat, the Segreteria Particolare del Duce, which meticulously briefed Mussolini about his visitors. If they had published a book, for example, guests frequently commented that they spotted a copy of it on Mussolini’s desk. It was a ceremony that was not left to chance and usually produced the desired effect on Mussolini’s visitors.33

Japanese were quick to recognize that one distinctive characteristic of Mussolini was the fact that he could be visited. A minor but regular presence at Palazzo Venezia, the Renaissance palace in central Rome that was home to Mussolini’s offices, a diverse crowd of Japanese artists, diplomats, politicians, journalists, and political activists visited Mussolini throughout the two decades of his rule.34 For many, being able to look Mussolini in the eye was awe-inspiring and confirmed the image of the Duce as a virile statesman. Okada Tadahiko, a former prefectural governor, head of the police department (keihōkyoku chō), and member of parliament for the Seiyūkai, was impressed by the leader’s physique, his “piercing eyes,” “large mouth,” and “sturdy chin.” When Okada wished Mussolini good health, he was immediately taken aback by the Duce’s retort: “My health doesn’t matter. The point is thinking about the future of Italy.” An awestruck Okada replied that “these words truly illustrate a politician’s resolve. I will keep them as a tale of my travels for the day when I return to Japan.”35

Some historians have connected the cult of the Duce to what they regard as the sacralization of politics under Fascism.36 It is striking, however, that the reports left by Japanese indicate that Mussolini impressed them for his ordinariness rather than his godlike stature (after all, in Japan, religion and politics mixed in a far more unequivocal manner in the figure of the emperor). A number of visitors commented on how an amiable Mussolini made them feel at ease. Takaishi Shingorō, a correspondent for the Osaka Mainichi, was granted an audience in 1928 accompanied by two other staff members from the newspaper and an American journalist with connections to Mussolini. At first anxious over the political topics that he would have to broach, Takaishi was relieved that his host displayed a keen interest in the promotional brochure about the city of Osaka that he had brought along. “Prime Minister Mussolini’s interest in the magazine exceeded our expectations,” he recalled. “He flipped through every single page from the beginning to the end and pointed to photos, asking for explanations…and we would answer that Osaka is an industrial and commercial city.” With his “passionate questions,” Takaishi went on, he made everyone feel comfortable—he even “happily” conceded to allow us to take a photograph and to give us an autograph. “The concerns we had before the audience and my plans about how to proceed in the conversation disappeared like snow in the spring in front of Prime Minister Mussolini’s humanity, his figure, and true feelings.”37

The picture of Mussolini is therefore a complex one. While some Japanese reviled him, it was also common to find comments glorifying him for his achievements. Yet perhaps most significant was the tendency, as exemplified by Takaishi, to humanize the Duce. By stressing his everyday characteristics, Japanese often disregarded that Mussolini was a dictator; after all, their primary concern was not Mussolini’s politics but the personality of the leader. Nagai Ryūtarō was most emphatic on this point. In an article published in 1927, titled “From Wilson to Mussolini,” Nagai argued that Mussolini ushered in a new stage in the history of politics because he had understood that a nation (minzoku) had a personality with a particular “desire for life” (seikatsu yōkyū) that required a particular form of “political organization.”38 Mussolini personified the global trend toward a “personality of a nation,” which, overriding Woodrow Wilson’s principle of national self-determination, would give birth to a new world order based on “coexistence and prosperity [kyōzon kyōei].” In line with these ideas, which he shared with Tsurumi Yūsuke, Nagai could not imagine a replica of Mussolini for Japan. Because he reflected the essence of Italy, Nagai concluded, “we cannot be satisfied with a model like Mussolini, but must make an effort to build a culture based on the peculiar personality of the Japanese people.”39 It was a statement that contradicted his earlier longing for a strong, “arrogant” politician; but it also reflected the wider ambivalence about the need for a figure like Mussolini.

A Moral Hero

In several quarters Mussolini was of interest less for his virtuosity as a political leader than as a model of ordinary moral leadership. Outside the realm of politics, the discourse on him reflected the aspiration of cultural critics, educators, and writers to reconstitute an individual subjectivity that was untouched by the commodification of modern life. As Miriam Silverberg has argued, in Japan the cultural revolution in the everyday life of the 1920s resulted in a tension between the individual as a consumer subject and as an imperial subject, with critics attacking materialistic individualism for undoing national cohesion.40 To them, Mussolini appeared to be a man who had found a way to a socially safe individualism, one that subordinated materialism to spirit and was premised on the mobilization of the self for the nation. It is therefore ironic that the Mussolini boom of the late 1920s was enabled by mass culture and consumerism, the very phenomenon that many of his admirers were committed to eliminating. His presence in radio, magazines, cinema, commercials, and popular theater suggests that, from the onset, mass culture could be reconciled with conservative politics.41 Indeed, Japanese consumer culture was overwhelmingly sympathetic to the Duce. Its producers pored over the life of Mussolini, presenting it as an example of individual success that was sanctioned by civic morality. In other words, they insisted that Mussolini had found a successful formula to combine individual success with the advancement of the nation. In so doing, they replicated the official Fascist narrative even as they made a conscious effort to direct their message to Japanese youth.

The two genres in which Mussolini became most visible in Japan were kabuki plays and biographies. Plays, perhaps, are a better indicator of the degree of stardom he had achieved in the late 1920s and, in turn, the role of mass culture in contributing to his myth. In the boom year of 1928, five theater pieces on the Duce were produced. The most striking adaptation of Mussolini for a mass audience was that of Kishida Tatsuya (1892–1944), a playwright for the all-female and greatly popular Takarazuka Revue.42 The second was the play “The World’s Great Man: Mussolini,” written by Tsubouchi Shikō, the nephew of the famous novelist and literary critic Tsubouchi Shōyō.43 Another was “Mussolini,” a high-profile piece written by Osanai Kaoru (1881–1928), the playwright and Japan’s leading director at this time, and featuring Ichikawa Sadanji II, the foremost actor of the interwar period.44 The left-wing writer Maedakō Hiroichirō (1888–1957) produced a drama (gikyoku) also entitled “Mussolini.” One other play by Numada Zōroku, a minor producer, was performed in Kyoto but is considered lost.

How can the production of these plays about Mussolini be explained? What did some of the most prominent actors and directors find appealing in the figure of the Duce? A number of answers are plausible. However much the plays contributed to the broad interest in Mussolini, his fame had preceded his appearance in kabuki theater. The activities of Shimoi, especially the Calpis affair and the uproar around the byakkōtai affair, as well as the general interest in the politics of Mussolini, probably made producers aware that there was a market for plays about him. At the same time, as James R. Brandon has shown, the production of plays based on contemporary political themes and personalities was not new. The Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) saw the birth of “new wave” (shinpa) theater, which characteristically responded to contemporary events in order to both inform and entertain Japan’s fledgling mass audiences.45 Later, the 1920s witnessed a boom of popular theater (taishū engeki) that led to “new drama” (shingeki), a genre that attempted to respond to social change through realism and psychological analysis. Mussolini, who made headlines and offered a distinctive persona, was ideally suited for both genres: he spoke the language of the people, was prone to pathos, and had a life that was already mythologized—ready-made for a mass audience. Also, the aesthetics of his regime facilitated the transposition of Mussolini into theater. The quintessential fascist political space, the piazza (city square), could conveniently be replicated on stage, along with Fascist rituals and paraphernalia such as marches, songs, and symbols. Kishida Tatsuya’s play, for example, reenacted the Fascist choreography that was associated with the dictator, especially the Blackshirts. Moreover, as a musical, it also reproduced Fascist songs, including the hymn of the Fascist Party (and unofficial Italian anthem) “Giovinezza” (Youth).46 The Duce, in short, possessed many of the qualities that 1920s playwrights sought.

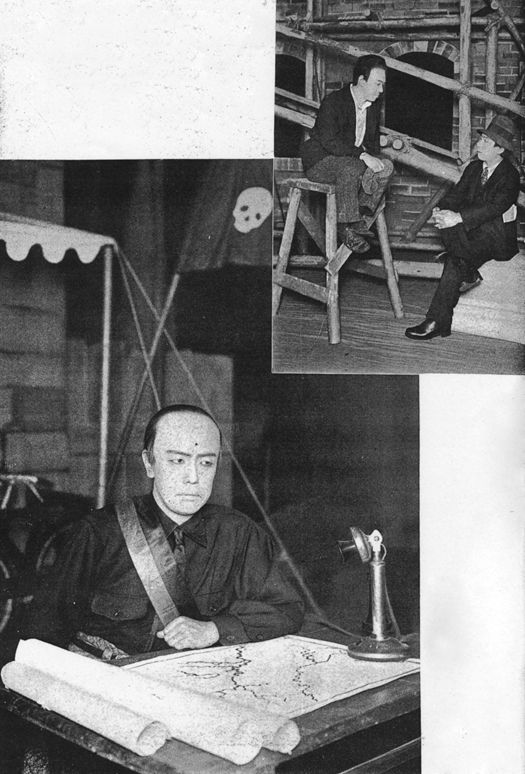

The actor Furukawa Toshitaka as Mussolini in Tsubouchi Shikō’s 1928 play Mussorini. To his left is Mori Eijirō and to his right Alfonso Gasco, Italian consul general in Kobe.

(From Takarazuka kokuminza kyakubon kaisetsu, no. 4 [1928]: 7.)

Writers and actors were not immune to the wider fascination with Mussolini. With the exception of Maedakō Hiroichirō, all playwrights expressed some degree of admiration for the Duce. Maedakō, a member of the literary current known as “proletarian literature” (puroretaria bungaku), presented an argument that reflected the Comintern theses on fascism, according to which Mussolini embodied bourgeois reaction against the proletariat. For this reason, but also at the behest of Italian authorities, his play was banned from being performed publicly (it did, however, appear, heavily censored, in the journal Kaizō in 1928).47 In contrast, Kishida Tatsuya praised Mussolini, especially for making Italy into a safe place to visit. The “kind” Blackshirts were to be credited for the “disappearance of Italy’s infamous fraudsters and mandatory tips.” In the opening scene of his play, the main actor calls Mussolini “god of loyalty and patriotism [chūkun aikoku].”48 Osanai Kaoru, though known for his left-leaning position, echoed Mussolini’s hatred of socialists, denouncing them in his play as “empty theorists, cowards, incompetents, and fence-sitters.” Ichikawa Sadanji, too, was well-disposed toward the Duce. Having been granted an audience with him in 1927, he described the encounter in the warmest of terms, lauding the Italian “great man,” whose “piercing glint in the eyes narrate half of the history of his life.”49

The actor Furukawa Toshitaka emulating Mussolini’s stare.

(From Nihon gikyoku zenshū, 43, 481.)

Although none of these playwrights can be considered a Fascist, their fondness for Mussolini and their desire to represent him through his emotions led them to replicate large parts of the Fascist self-narrative. This approach is particularly visible in Tsubouchi Shikō’s declaration that he aspired to tell Mussolini’s story not “by stressing ideologies” but through the Duce’s own “feelings.”50 Relativizing—if not effectively legitimizing—Mussolini’s thought and actions, Tsubouchi’s “Mussolini” was a portrayal of a hero who, by virtue of his sense of loyalty to the nation, rescued his country from political and moral collapse. His narrative stressed how the patriotism of Mussolini and the Fascists had restored social order in Italy. Even Fascist violence, Tsubouchi, argued, had to be understood in this context. Whereas the socialist Maedakō criticized the bourgeois readiness to resort to violence to repress proletarian organizations, Tsubouchi turned this argument on its head. In his story, it was the socialists, not the Fascists, who bore the brunt of the responsibility for the disorder that caused widespread violence. In other words, the Left’s attempt to bring about social revolution prompted the nationalist reaction of Mussolini. One telling example of this inversion of violence is a scene set in a tavern. Three drunk socialists begin molesting a waitress and threatening her brother, a young soldier who has just returned from the war.

Socialist: I hate you for having been a soldier.

Brother: Why?

…

Brother: I am a man who has loyally done his duty as a citizen for the state and King Emmanuel….

Socialist: What benefits did we draw from your fighting? You lot are the running dogs of capitalist wartime profiteers [narikin].

This exchange is emblematic of Tsubouchi’s picture of a society in disarray that Mussolini rescued by reasserting law and order. Tsubouchi declared the Fascists an inevitable, and welcome, outcome. In his play the Italian Left is described as a pawn of the Soviets and, as such, a threat to the stability of the state; the liberal establishment, led by weak statesmen—in particular Luigi Facta, the prime minister who preceded Mussolini—is shown to be ineffective in managing the situation, paving the way for social chaos. As one war veteran puts it: “I was in the army. I heard some rumors [about this situation], but I didn’t imagine things to be like this. It’s absolute disorder [muchitsujo].”51 The Fascists, then, come to the rescue. In the words of a Blackshirt, “we, with barely fifty comrades, have shown how to do what the government has been unable to do.”52

Tsubouchi cut a figure of a Mussolini in whom physical prowess and psychic vitality fed off one another. When Mussolini is hospitalized for injuries he had suffered in a battle during World War I, one roommate expresses his disbelief that he could have survived the misfortune.

Absolutely, that man’s physique [shintai] is different from ours. Immortal, that’s what he is. Bullets don’t seem to bother him. He has thirty-one of them in his body, but with that condition I’ve no idea what’s going to happen. That man is superior to Garibaldi.53

Wheeling Mussolini into his hospital room, the nurse informs the onlookers that the prominent patient has high fever.

All: 42 degrees?

Nurse 3: Even the doctor was surprised. And even with 42 degrees he is writing and reading without interruption—that can’t be the work of man [ningenwaza].

Soldier 2: [To Mussolini] Hey, you, what are you writing?

Nurse 3: He’s writing a report to the nation [kuni]….

Soldier 4: Hey, Mussolini, what are you reading so desperately?

Mussolini: Russian.

Mussolini, irritated by all this talk, proceeds to lecture the incredulous crowd on the spiritual origins of his strength.

Mussolini: What are 40 degrees? Let’s look at a man’s [danshi] will [iki], at the will of a man! I will not die, I will not die, I absolutely will not die. I, on the battlefield, when I faced the enemy, was never afraid.…The battle is, first of all, with oneself. The person to carry it through is me. The person to rescue the state of Italy is me. Me!

Hearing these words, a soldier wonders whether Mussolini is “more of a dreamer than D’Annunzio,” but is immediately challenged by two companions. Mussolini, they explain, is a “passionate patriot,” “a man of vigor” (seiryokuka). The skeptical soldier ought to understand that, unlike the socialists and other weak-headed parliamentarians, Mussolini is not a man who delights in lengthy discussions. His vision is about “showing complete discipline for the nation” (honbun kiritsu), having “duties [gimu] not rights [kenri],” and engaging in “action [jikkō] not debates [giron].”54

For Tsubouchi, Mussolini deserved a place in the genealogy of great Italian men. Constructing a national narrative of heroism, Tsubouchi drew a straight line from Giuseppe Garibaldi, the nineteenth-century hero of Italian national unification, to Gabriele D’Annunzio, and ultimately, to Mussolini. Indeed, it is D’Annunzio, the venerable poet, who salutes the youthful Mussolini as his heir.

D’Annunzio: Oh! Our brave man [yūshi] Mussolini! Everyone, here he is, here is the hero [eiyū] who will rule the Italy of the future….

D’Annunzio: So, since you are already in command, I am now thinking of returning home [kokyō]. What are your plans after this?

Mussolini: I am aiming at Rome, a march on our capital Rome.…my highest aim is to perform a great surgery to bring Italy back to life.

D’Annunzio: A march on Rome, ah, that’s interesting, just hearing this cheers my heart. You already have made up your mind [iki], what else can I say?

Mussolini: Thank you.

D’Annunzio: I pray for your success, young patriot!

Mussolini: I pray for your health, ardent great poet!

D’Annunzio: Adieu, adieu.55

Emphasizing what they perceived as Mussolini’s extraordinary qualities—an iron will, patriotism, loyalty—playwrights proposed these traits as desirable for a moral redress of ordinary Japanese, especially youth.

That in Japan the imagined life of Mussolini reflected less the cult of a political leader than the cultivation of youth through moral leadership also emerges in several biographies of the Duce that were published in these years. As Luisa Passerini has suggested in her study of Italian biographies of Mussolini, in the 1920s there was a wider aspiration to extrapolate the individual from a discourse on the social: contemporaries felt that “individuals had become anonymous, but biographies recovered them, giving them a stamp of official recognition.”56 What was more distinctively Japanese, though, was how the biographical proliferation of works on Mussolini bridged the late Meiji discourse on the despondency of youth with the 1920s question of declining social mobility. Responding to the concern that also animated Shimoi Harukichi, biographies of Mussolini lent themselves to the recasting of young Japanese as leading protagonists in a heroic national narrative—whether as aspiring leaders or as individuals committed to simple acts of everyday heroism.

Given that biographies were a popular genre in the 1920s, it is not surprising that Mussolini was only one of many “great men” (ijin) who had his life recounted by Japanese writers. In this sense, he was placed with a multitude of legendary men (and, occasionally, women): William Gladstone, Fukuzawa Yūkichi, and Jeanne D’Arc are just a few names of these individuals, Japanese but often also foreign, who were of interest to biographers. Years later, Nakagawa Shigeru, a prolific biographer, included a study of Mussolini in a vast collection of some eighty volumes on “great men” stretching across continents and centuries.57 Biographers had a predilection for patriotic figures of the past, usually statesmen, but they also wrote about contemporary men who epitomized individual success. In 1928, for example, a little-known biographer from Osaka named Okumura Takeshi published Wonder Man Mussolini and, in the same year, Henry Ford: King of the Automobile.58 But for biographers Mussolini’s life had a distinctive quality. It simultaneously evidenced national fervor and strenuous efforts to rise in society. Here was an individual whose life bridged a narrative of patriotism associated with men of the past and a narrative of success characteristic of the present, and this helps to account for the proliferation of his biographies.

To write their works, Japanese biographers relied on a wide range of accounts of Mussolini published in English, German, and French. This international corpus encompassed a spectrum that ranged from hagiographic official biographies to publications that were outspokenly critical of Fascism and its leader. The classic Italian biography of the Duce by his lover, the journalist Margherita Sarfatti, considered a “progenitor” of other Mussolini biographies, was partly translated into Japanese in 1926, and local biographers drew freely from this adulatory tribute.59 But a number of works on the Duce were decidedly unfavorable, and Japanese biographers read those as well. Sawada Ken, who in 1928 wrote the closest thing to a standard Japanese biography of Mussolini, counted among his sources the works of several pro-Fascist writers, such as Giuseppe Prezzolini, Luigi Villari, and Pietro Gorgolini.60 But he also cited Luigi Sturzo, a priest and politician in exile in London and New York; the liberal historian, journalist, and novelist Guglielmo Ferrero, placed under house arrest by the Fascist regime and later an émigré to Geneva; and Ivanoe Bonomi, lawyer and liberal prime minister.61

Yet, despite the available range of diverse points of view on Mussolini, Japanese wrote positive biographies of the Duce. Although authors often had reservations about his domestic repression, antiunion violence, and censorship, they could not resist flattering commentary when it came to his persona. “Mussolini, man of doubt! Great sphinx of reaction! Go as far as you can!” wrote one editor.62 Japanese biographers were unconvinced by critical political commentary—or perhaps they chose to disregard this aspect. Instead, selectively separating the public from the private Mussolini, they drew a portrait of the Italian leader whom, for all his shortcomings, they saw as a great man, often in his very ordinariness. Emphasizing the earlier years of his life, these works focused on how the young Benito built up a strong personality despite—indeed, thanks to—a life of hardship. They stressed his poverty, his countryside upbringing, his emigration to Switzerland, and finally, his conversion from socialism to nationalism. Thus, as no Japanese wrote an anti-Fascist counter-biography, this powerful means of defining the image of Mussolini was left to conservative commentators, who adapted for Japanese consumption the hagiographic clichés originating from the official image of Mussolini in Italy.

The view that Mussolini possessed the moral qualities desirable to foster in Japanese youth was an explicit theme in the biography of Sawada Ken (1894–1969). He had begun his career after World War I as a commentator on international affairs but in the 1920s shifted his attention to biography, just as he turned markedly to the right. In writing the lives of great individuals, Sawada drew portraits of leaders who, to his mind, advanced the interests of their nations regardless of whether they were democrats or dictators. In line with this conviction, Sawada narrated the lives of the American heroes of mass production Henry Ford and Thomas Edison; the Japanese bureaucrat, entrepreneur, and politician Gotō Shimpei; and the fascist leaders Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, the latter two books going through three editions.63

In his biography of Mussolini, The Story of Mussolini (Mussorini-den, 1928) Sawada championed the Duce as a model of moral leadership that could inspire Japanese youth to overcome the mediocrity of the present. “In present-day Japan, are we not in a time that necessitates a man with a strong personality like Mussolini? The trickery of conservative bigots. The malady in debates of the communists. The evasions of decrepit liberals. Are we not looking forward to the construction of a new Japan by the power of our strong youth?”64 Mussolini, Sawada argued, was not without his faults, but he ought to be admired for shouldering the responsibility of making a clean sweep of the mess created by the political establishment. “There are many points for which we should criticize Mussolini’s politics. I acknowledge this. But if we blame Mussolini’s politics, we should turn the blame largely on the generation of politicians that has preceded him. They should be our concern and the targets of our attacks.”65 For Sawada, instilling youth with Mussolinian morality would mean creating a generational change. “The force to rescue Japan, the force to build up a new Japan is no longer in the hands of the gentlemen in frock-coats or the sickly, visionary, armchair experts mimicking Western letters.…That force is in our patriotic youth.”66 Mobilizing youth through the example of Mussolini, however, would not give way to Fascism but enact a political reform that was autochthonous. “Ah, where is Japan going? Quo vadis, Japone!…May Japan’s heroic children produce a truly Japanese, neoliberal, constitutional [rikkenteki] hero.”67

Sawada’s call for a “neoliberal political movement” (shinjiyūshugi seiji undō) is noteworthy. In his view, liberalism did not need to be replaced with a dictatorship but could be rejuvenated through the kind of national mobilization of the individual that Mussolini had pioneered. As far as the quest for leadership was concerned, there was compatibility between Fascism and liberalism, even though the former needed an overbearing Duce while the latter required a new generation of national leaders who would act within the parameters of Japan’s social and political status quo.

Similar concerns motivated the novelist and journalist Usuda Zan’un (1877–1956) to write a biography of Mussolini, also in 1928. In earlier years, Usuda had written a series titled Popular World History published by Waseda University, of which he was a graduate. This experience convinced him that the best way to spread knowledge about the world was by writing about individuals who embodied their nations, and he believed that Mussolini did that more than any other living figure. As is suggested by the title of his book, I Am Mussolini (Wagahai wa Mussorini de aru), Usuda wrote a fictional autobiography. Much had been written about the Duce, he admitted, but it was largely “political commentary [hyōron].” So far no biography had examined the man’s life in detail. So, in writing I Am Mussolini, he aimed to write the story of the life of “a central figure in [our] times” through his “character and conduct,” by “diving into Mussolini’s womb as if he were Buddha [tainai kuguri].” The result was a narrative that repeated the recurring themes surrounding Mussolini—his family background, his performance at school, his experience as a migrant in Switzerland. The use of the first person “I” added psychological pathos.68

Usuda’s biography was peculiar in one respect. As no doubt most readers were aware, the title echoed that of a work by the famous novelist Natsume Sōseki, I Am a Cat (Wagahai wa neko de aru, 1906). This novel was a satire, narrated from the perspective of a cat, of late nineteenth-century Japanese society, which was torn between Western and Japanese thought. By evoking this book, Usuda was arguing that similar questions of national identity were as yet unresolved. But by making Mussolini his main character, he also indicated that here was someone who had overcome the dilemma through his loyalty to the Italian people and the state. Like Sawada’s biography, Usuda’s I Am Mussolini was written with a conscious allegorical intent.69

In biographies for youth, then, Mussolini served as a means to reimagine the relationship between the individual and the nation. But there was another category of biographies: those intended for children. In interwar Japan, as Mark Jones has shown, the notion of childhood became a central site of class competition. Educators, journalists, and child experts produced three visions of the modern child. One, associated with the aspiring middle classes, championed the “superior student” (yūtōsei), a notion that emphasized a child’s capacity to overcome difficulties and strive for meritocratic success. Another was the ideal of the established elites, who advanced a romantic image of a “childlike child” (kodomorashii kodomo), one that shunned materialistic advancement in favor of cultivating a child’s emotions and experiences in the world. The third was the “little citizen” (shōkokumin), a child raised by a “wise mother” who “valued the child as a national possession trained to possess moral fortitude and physical vigor.”70 What emerges from biographies of Mussolini for children is that they were able to deploy the young Benito for all three categories. The Duce, in other words, represented both the ideal of a talented boy who strove to make it in the modern world and that of a child who was reared with “traditional” family values and who therefore was an exemplary citizen.

As was the case for those who wrote biographies of Mussolini for youth, biographers for children had also practiced their trade for some time before turning to the Duce. Some authors were established writers of children’s literature, such as Abe Sueo (1880–1962), Matsudaira Michio (1901–1964), and Ashima Kei (1895–?); they had published biographies of Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin, but also of modern Japanese figures such as the Meiji educator and politician Tsuji Shinji (1842–1915). Others were of a minor stature, often associated with provincial and local educational associations. Ueda Sakuichi, who wrote a biography of Mussolini in 1926, was a member of the Osaka People’s Education Research Association (Kōmin kyōiku kenkyūkai).71 And like other biographers, these authors, too, elevated Mussolini to the status of a great man. To one editor Mussolini proved that “it is a mistake to argue that the age of reverence for heroes [eiyū sūhai] has already come to a close.”72

What distinguished these biographers was the fact that they associated Mussolini’s heroism with moral values that transcended class boundaries. In the effort to promote social harmony, they sought certain traits of Mussolini that would appeal to all Japanese, regardless of whether they were urban workers, bureaucratic elites, or peasants. One characteristic of Mussolini that all of them emphasized was his commitment to the family (thus ignoring his reputation as a womanizer). Traditional Japanese family values and obligations, it seemed to middle-class intellectuals, were being eroded by modern lifestyles. They contended that new forms of leisure like jazz and cinema, participation in political activities, and the lure of the department store led to the birth of a generation at the mercy of either American or Soviet materialism, steeped in the pursuit of individual or class interests. Mussolini provided a counterimage of familial devotion in which generational and gender hierarchies were respected, teaching that the family was the individual’s real unit of social identification.

In biographies of Mussolini written for children, family bonding often revolved around parental figures, evoking an ideal of authority based on the notion of filial piety (oya kōkō). As in official Italian biographies, Mussolini’s mother, Rosa, often emerges as the symbol of what many middle-class Japanese would identify as a “good wife, wise mother” (ryōsai kenbo).73 In these biographies Mussolini frequently expresses his affection toward his mother. “Since my childhood I devoted my greatest love to my mother.”74 In a departure from Italian models, however, Rosa is described as a wife who, in spite of the domestic difficulties caused by her violent, alcoholic husband, loyally takes care of him and the young children, “managing the household and trying not to neglect her obligations toward other people.” Even Mussolini’s father, despite his vices and temperament, remained a figure from whom the young Benito had something to learn. One biographer made an explicit connection between the father’s occupation—he was a blacksmith—and the son’s iron will.75 Conversely, Mussolini could be made to embody the father figure. Abe, for example, begins with an episode of a young boy who, weeping, misbehaves because his mother will not introduce him to Mussolini. The Duce, suddenly appearing on horseback, takes the child for a ride. The boy, initially unaware of the identity of the good uncle (ojisan), is exhilarated with joy when he is told that the man who was riding with him was no less than the Duce himself, shouting “Italy, banzai!”76

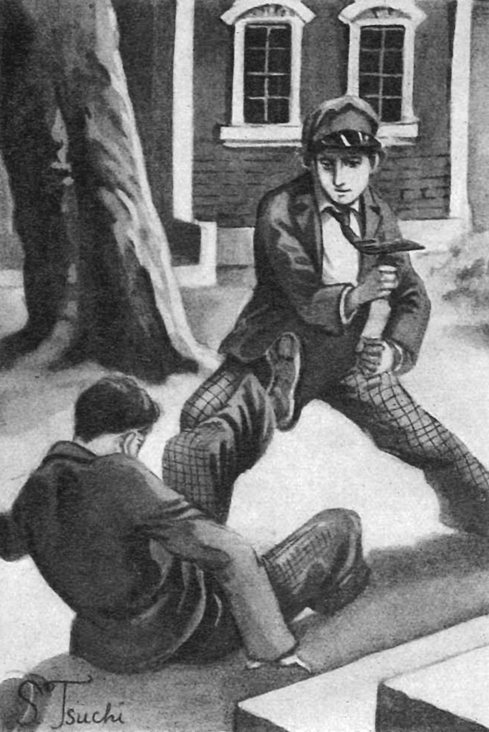

Mussolini’s masculinity was another recurring theme in biographies written for children. It was well known that in reality Mussolini’s virility easily gave way to violence; but also in this respect biographers found ways to mitigate the Duce’s excesses. Dwelling on other aspects of his character, they reinforced the image of a moral Mussolini who balanced personal impulse with camaraderie. Matsudaira Michio, for example, narrates that Mussolini was a “bully” (gaki taishō) prone to picking fights with schoolmates, even as he presents him as a “warmhearted [ninjō no atsui] youngster with plenty of chivalry.” Matsudaira explains that one day the young Benito and a friend decide to help themselves to the apples of a nearby peasant. Catching him in the act of climbing the tree, the peasant accidentally fires a shot into the friend’s leg. Benito, instead of running for it, attends to his friend, using his handkerchief to bandage the wounded leg. “How does it feel? Is it still painful? Hmm, don’t cry, you are a brave fellow [yūshi]. Only your honor has been injured. Is there a man [yatsu] who, being injured in his honor, cries? Come on, let’s go. You can’t walk? All right, I’ll carry you on my shoulders.” Mussolini’s capacity for this male to male bonding is such as to bring even the angry peasant to express his admiration. “That brat, I think one day he’ll become something [erai mono]. He’s so different from the usual brats.”77

Biographers interwove Mussolini’s life with one further social issue that was coming to prominence in the 1920s: the relationship between city and countryside. State-minded and bureaucratically inclined individuals like educators were particularly sensitive to the growing economic disparity between the major urban centers and rural villages because they romanticized the peasant community as a space resistant to modern class conflict.78 They worried that modern life was luring vast numbers of young Japanese to the cities, where they replaced their ideals of social harmony with a spirit of competition. In the context of this discourse on the “village” (nōson), biographers found in Mussolini a counterpoint to the perceived crisis. Presenting him as a rural migrant—and overstating the poverty of his family—they emphasized the hardships he had faced as he sought to improve his life, intimating that he responded to the challenges of mass society in an exemplary way.

Violent yet virile, Mussolini bullies a classmate. Biographies for children commonly featured imaginary representations of the Duce’s life.

(From Matsudaira Michio, Mussorini [Tokyo: Kin no seisha, 1928].)

From his travails, biographers constantly pointed out, Mussolini accumulated wisdom, not wealth; a sense of national harmony, not ideas of class conflict. Abe, for example, called Predappio, Mussolini’s hometown, an “impoverished village” (kanson) whose inhabitants were “hard workers” and who had a distinct “love for their hometown” and “pride in their region.”79 A sense of community, therefore, was innate in Mussolini. This attachment to the people, Abe explained, was the reason why Mussolini renounced socialist theories of class conflict in favor of a vision of harmony among Italians. The lesson for Abe’s young readers was that poverty should not become a reason for resentment. Far from it, poverty actually generated spiritual wealth. Would Japan’s future leaders come from the countryside? The countryside, for all its current misery, was fundamental to the nation, as it contributed to its greatness by offering to the state moral resources in the form of patriotic young men.

Linking community, sacrifice, and violence, biographies of Mussolini only barely concealed a discourse on blood and soil. The harmonious social vision put forth in these texts rested, ultimately, on the assumption that young men had to be ready to die for their nation. Respect “the state,” “devote yourself to the soil [tochi], the people [kokumin], history, and spirit [seishin]…throw away your passions, and strive to fulfill the passions of Japan,” Ashima exhorted his young readers.80 It was no coincidence that illustrations in many books portrayed a warrior Mussolini on horseback, not wearing the uniform of the Blackshirts but that of the army. Military service, and the willingness to die for Japan, was the ultimate expression of an individual’s elevation of the nation above all other forms of identity. “Through obedience, discipline, and training, the self will become grand for the first time, leading us to a great freedom. Mussolini teaches us this.”81

Thus, whether as a political leader or as an ideal of leadership, Mussolini had a meaning beyond Italy. No one made this point clearer than Furukawa Toshitaka, who had impersonated Mussolini in Tsubouchi’s play. “Unfortunate was Italy’s need for Mussolini, but fortunate was Italy’s finding of Mussolini. Is Japan not also falling into a misfortune by requiring someone of the earnestness and ability of Mussolini?”82 This question was the driving force of the Mussolini boom, asked by liberals and conservatives alike.

Their answers were ambiguous. In fact, it is remarkable that the popularity of Mussolini coexisted with a wide range of reservations about his style, rule, and politics. For Mussolini was portrayed as tragic and comic; heroic and bombastic; transcendental and commercial; popular and vulgar; timeless and quotidian; politician and celebrity; Italian and global. In Japan there was little interest in merging cultural and political leadership in one person, let alone adopting a ready-made foreign leader. And yet, the misgivings about the Duce’s style, rule, and repression went hand in hand with his fame as a youthful and vigorous leader. As both liberals and conservatives sought a solution to the shortcomings of parliamentarism—and the underlying degeneration of politics—they found in Mussolini a set of personal qualities and institutional strategies usable to forge consent among rulers and ruled. Their eagerness to learn from Fascist notions of leadership demonstrates that Mussolini also had a meaning beyond fascism. The spirit, courage, and will that were characteristic of Mussolini, argued the biographer Ashima Kei, were necessary in any country at any time—also in Japan. “But if people with such spirit and courage were to arise in Japan, they would not become heroes like Mussolini. Instead they would become outstanding great men (kyojin) in all fields of society.”83 As the interwar crisis came to a head in the 1930s, fuelled by the Great Depression and expressed by imperial expansion in Asia and turmoil at home, the call for heroes and heroism entered a new phase.